Introduction

The main objective of this paper is to gather new objective data to better understand effective labour regulation in Senegal and, to a lesser extent, in the other eight countries that constitute Francophone West Africa: Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Togo. These countries are among the poorest in the world, have one of the highest rates of population growth, and are heavily under-researched in economics (Das et al Reference Das, Do, Shaines and Srikant2013).

Effective labour regulation is defined as the combination of in-form regulation and enforcement efforts, where in-form labour regulation refers to the letter of the labour code, as opposed to the actual behaviour of employers and workers. Throughout the paper, we use law-in-the-books, de jure, and in-form interchangeably.

There are three aspects about labour markets and regulations in this region that are well documented: First, countries have quite protective/rigid in-form labour regulations. A prominent example is Senegal, a country that ranks among the worst performers according to the World Bank’s Doing Business labour flexibility metric.Footnote 1 Second, we also know that real working conditions are poor for most of the workforce (Williams and Schneider Reference Williams and Schneider2016). In West Africa, the share of workers in formal employment (i.e. with access to labour benefits such as social security contributions) is as low as only 8% (ILO 2018). The remaining 92% are informally employed, that is, without access to labour benefits. They are informally employed either because they are de jure uncovered, such as low-skilled self-employees, or because they are salaried workers, but are de facto uncovered because their employers do not comply with the law.Footnote 2

Third, violations of workers’ rights are significantly more prevalent in informal/unregistered firms compared with formal/registered firms. This fact has been well documented quantitatively in other low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), but less so in Senegal. Therefore, we process the Enquête nationale sur l’emploi au Senegal (ENES).Footnote 3 We estimate that only 1.8% of employees working in informal/unregistered firms have social security contributions and 1.3% have paid vacations, compared with 46.2% and 42%, respectively, among employees working in formal/registered firms. Despite these three facts, we have very little hard data and knowledge about labour enforcement in the region (Kanbur and Ronconi Reference Kanbur and Ronconi2018).

The enforcement data we gather allow us to contribute to various literatures and to challenge two commonly accepted assumptions. First, the conventional wisdom in neoclassical labour economics is that the state is heavily involved in the regulation of labour markets in Francophone West Africa (Botero et al Reference Botero, Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer2004; Djankov and Ramalho Reference Djankov and Ramalho2009; Rodríguez-Castelán and Vázquez Reference Rodríguez-Castelán and Vázquez2022). This paper shows a substantially different and more complex picture, wherein relatively stringent/protective in-form labour regulations coexist with exceptionally low levels of enforcement and compliance. Second, while legal scholars usually note the lack of labour enforcement in LMIC, they tend to assume that it is mostly due to lack of financial resources (ILO 2011; Samba Reference Samba2021). For example, Marshall and Fenwick (Reference Marshall and Fenwick2016, 11) argue that [in LMIC] ‘the law on the books is not applied effectively in practice: labour laws are weakly enforced by state inspectorates, and trade unions and civil society bodies may have limited capacity to fill that gap. State inspectorates are small and poorly funded…’ The data we gather show that inspection resources in Senegal focus overwhelmingly on large and formal firms, which is precisely where labour violations are less prevalent. This fact is at odds with the belief that compliance problems could be solved by simply injecting more money into the state inspectorate.

Our key contribution is to bring a comprehensive view of enforcement to the forefront. In the case of labour, enforcement includes fines and penalties, workers’ knowledge about their rights, and the functioning of the judiciary and the labour inspectorate. It can also include corporate social responsibility and the monitoring activities of labour unions and civil society organisations. While much comparative research has been conducted about in-form labour regulations, particularly since the contributions of Botero et al (Reference Botero, Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer2004), Armour et al (Reference Armour, Deakin and Siems2016), and the World Bank’s Doing Business initiative, there is still relatively little and quite incomplete empirical evidence about enforcement.

First, extant research on labour enforcement has made interesting contributions, but only covering some components. An example is the literature on the private enforcement of global corporate conduct (Nadvi Reference Nadvi2008; Vogel Reference Vogel2010), and on the participation of labour unions and NGOs in producing co-enforcement (Amengual and Fine Reference Amengual and Fine2017; Hastings Reference Hastings2019; Hastings and Herod Reference Hastings and Herod2023). But these are only some components of enforcement. They say little about public inspections, penalties, and the functioning of the judiciary. Second, because most vulnerable workers in Africa are not unionised and are employed in small informal firms in the non-tradable sector, they are usually not reached by those non-state initiatives.Footnote 4 Third, while several recent studies are measuring public labour enforcement and state inspections, they are mostly focused on Latin America. Some examples are Samaniego de la Parra and Fernández Bujanda (Reference Samaniego de la Parra and Fernández Bujanda2024) for Mexico, Gindling et al (Reference Gindling, Mossaad and Trejos2015) for Costa Rica, Pires (Reference Pires2008) for Brazil, and Ronconi (Reference Ronconi2010) for Argentina. Particularly little is known about public labour enforcement in Africa. Fourth, extant studies usually rely on one source of administrative data or interviews with one specific actor. In this study, we interview workers, labour inspectors, and employers in Senegal and collect administrative data from various sources for the nine countries of Francophone West Africa to provide a more comprehensive view of enforcement and fill some of the gaps that exist in the literature.

Beyond purely academic interest, our work attempts to inform the policy debate. Theoretically, the effects of labour regulation are ambiguous, depending on many characteristics such as the power of employers in the labour market. Thus, we need solid empirical evidence to make policy recommendations. Providing solid evidence requires including enforcement into the analysis because employers and workers care more about the actual costs and benefits of working conditions, rather than about in-form regulations that can be costlessly ignored. Therefore, an incomplete picture emerges from empirical studies that only explore the links between in-form regulation and outcomes.

Scholars, from different traditions and disciplines, have analysed the relationship between employment protection legislation (EPL) and various outcomes, finding contradictory results. On the one hand, there are studies that suggest that EPL is positively related to labour outcomes (Galli and Kucera Reference Galli and Kucera2004; Deakin and Sarkar Reference Deakin and Sarkar2008; Deakin et al Reference Deakin, Malmberg and Sarkar2014; Adams et al Reference Adams, Bishop, Deakin, Fenwick, Martinsson and Rusconi2019). But on the other hand, other research suggests that EPL is negatively related with outcomes (Botero et al Reference Botero, Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer2004; Djankov and Ramalho Reference Djankov and Ramalho2009; Heckman and Pages Reference Heckman and Pages2004). All these studies, however, have one characteristic in common. They only consider variation in the letter of the law but do not include enforcement into the analysis (Bhattacharjea Reference Bhattacharjea2006). This is problematic in LMIC since the political economy literature suggests that enforcement can be negatively correlated with the level of protection/rigidity of labour law producing endogeneity bias (Kanbur and Ronconi Reference Kanbur and Ronconi2018). Our work attempts to complement the existing policy-oriented debate by bringing enforcement to the forefront.

For example, Rodríguez-Castelán and Vázquez (Reference Rodríguez-Castelán and Vázquez2022, 14) argue:

‘Policy reforms [in Senegal] should also aim at increasing flexibility of the labour market as the country ranks among the top countries in the world in terms of labour rigidities. Some policy options should include reduction of burdensome regulation, tax policy adjustments, cutting the cost of hiring and firing, and administrative simplification’.Footnote 5

But, in our view, the existing evidence is still quite inconclusive and insufficient to make a strong policy recommendation. Again, the shifts in the demand and supply of labour are reactions to effective regulations, not necessarily to in-form regulations that can be easily ignored. Therefore, scholarly research attempting to understand the effects of labour regulation in countries where compliance with the law is partial, should irremediably include enforcement.

The paper is organised as follows: The next section presents the methodology. The third section presents novel quantitative and qualitative evidence describing the functioning of labour enforcement institutions in Francophone West African countries in general, and in Senegal in particular. The fourth section analyses the findings in relation to theories and policy narratives, and finally, we conclude.

Methodology

Conceptually, the objective is to measure actions, mostly state actions, aimed at achieving compliance with labour regulations. We focus on Senegal, but for some metrics, we cover every Francophone West African country as well.Footnote 6 Actions aimed at achieving compliance can be categorised into two groups: first, actions that affect the probability of finding employers who violate the law, and second, actions that determine the expected penalty. Government inspections, trade union monitoring, access to the judiciary, and public campaigns to provide workers with information about their rights, are in the first group. Codified penalties and their effective implementation by labour inspectors and judges, as well as consumer boycotts, are in the second group. All these actions can deter the employer from violating the labour code since they increase the expected monetary cost of doing so.Footnote 7 This article covers a subset of the above actions.

One of the main policy instruments to enforce labour regulations is government inspection. In Senegal, as well as in other Francophone West African countries, this is usually conducted by a generalist labour inspectorate that controls all labour standards, as it is in France. This is very different from the USA and the UK, where several specialised agencies enforce different components of the employment relationship (Piore and Schrank Reference Piore and Schrank2008).

Regrettably, there is no single source of information to measure the resources and activities of labour inspection agencies across countries and over time. The ILOSTAT dataset does not provide any data for Senegal or the other four countries in the region; it only provides data for one single year for Burkina Faso, Guinea, Niger, and Togo. Therefore, we conduct an extensive in-desk review of official documents, government websites, online media, and published reports and papers. We follow the methodology described in Ronconi (Reference Ronconi2012) and add more recent data. More specifically, we measure the number of labour inspectors and labour inspections conducted per year by the government (per 100,000 workers), at two points in time: Between 2010 and 2012 (which we refer as ‘2011’) and between 2019 and 2021 (which we refer as ‘2020’). This allows comparing variation across countries and over time during the last decade.

An important advantage of these measures is that they are objective, that is, not based on subjective opinions.Footnote 8 They cover, however, only a subset of the components of enforcement. For example, we measure the number of inspectors and the number of firms they inspect in a country-year, but such data does not tell whether the inspections properly targeted non-compliers or whether the inspectors accept bribes in exchange for turning a blind eye to labour violations. These are major limitations to inform the policy debate. Without that information, it is infeasible to know whether enforcement problems in LMIC are mostly due to lack of funding or have more complex causes.

Therefore, we complement the quantitative evidence with qualitative data obtained from interviews we conducted with employees, employers, and labour inspectors in Senegal. That is, the quantitative data set a comparative context of Senegal with its peers in the region, and the qualitative data zoom in on several specific issues. We focus on Senegal because of our logistical limitations and our first-hand experience. Note that Senegal is an extreme case in terms of stringent in-form labour regulations (Golub et al Reference Golub and Mbaye2015). Hence, from the usual assumption that in-form regulations are an adequate proxy for effective regulation, Senegal represents a most likely scenario for observing high levels of enforcement. Finding that enforcement is very low in Senegal would cast serious doubts about the accuracy of proxying EPL by a de jure measure.

We interviewed informal employees,Footnote 9 informal employers, and labour inspectors in Dakar and Saint-Louis (Senegal).Footnote 10 The interviews aimed to generate deeper insights and critical knowledge about enforcement of labour regulations. The data collection was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, that took place during October and November 2022, we interviewed 21 informal employees, 6 informal employers, and 6 labour inspectors. Triangulating their viewpoints improves the validity of the analysis. We used three interview guides, each of which featured both closed and open-ended questions to allow key informants (KIs) to describe their experiences and make the interviews feel like a conversation. During the first stage, to increase the chances of collecting information-rich and truthful responses, we followed a ‘purposeful sampling’ approach, wherein we only interviewed individuals we personally knew or had good references (Patton Reference Patton2002). To capture the entire view of the person, interviews were conducted until saturation was reached. The response rate was 100%.

One limitation of this approach is that the informal employees we interviewed during the first stage are, on average, substantially more educated than the typical informal worker in Senegal.Footnote 11 While it is beyond the scope of this paper providing estimates based on a large N sample, we wanted a socioeconomically more representative sample. Therefore, in the second stage, we interviewed 20 additional informal employees with an educational background not above primary level. These individuals were interviewed during June 2023, and the response rate was 77%. All the informal employees we interviewed during both stages reported working for different firms, except for two who worked for the same employer.

KIs were informed of the purpose of the study prior to obtaining their consent. In addition, they were reassured that all data would remain confidential and used only for research purposes. During the transcription process, each key informant was assigned a unique code to ensure anonymity. Informal employees, employers, and inspectors were assigned alphabets beginning with A1, B1, and C1, respectively. Seventy-three per cent of the interviews were conducted in Wolof, the lingua franca of Senegal, and 27% in French.

Finally, it is important to note that our initial objective was to interview several informal employers and employees who experienced at least one labour inspection in their lifetime. However, it was particularly difficult to find people in that situation, and we ended up finding and interviewing only two informal employees who had experienced labour inspection. This is initial indication that inspectors in Senegal largely focus on the formal sector.

Results

Quantitative study results

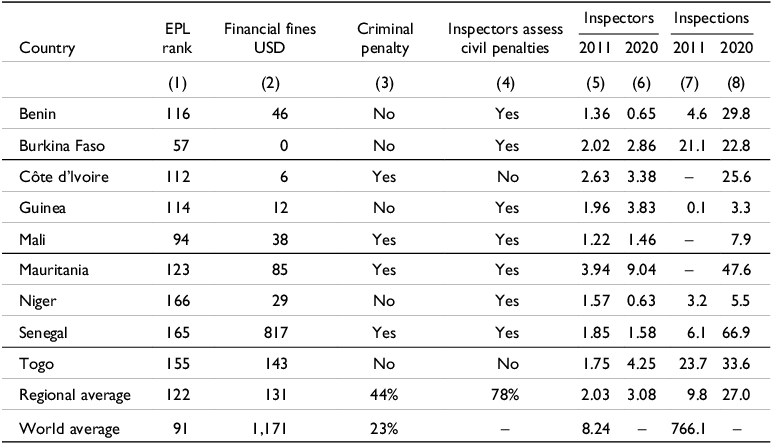

The quantitative data we gathered are in Table 1. In 2011, countries in the region had between 1 and 4 labour inspectors per 100,000 workers and an average of two. This figure is substantially lower compared to other countries in the world, where the average in 2011 was 8 labour inspectors per 100,000 workers (Kanbur and Ronconi Reference Kanbur and Ronconi2018).Footnote 12 Differences in inspection activities across regions, however, are even larger than differences in human resources. In 2011, on average, only 10 firms were inspected per year per 100,000 workers in Francophone West African countries, compared to almost 800 firms in the world.

Table 1. Effective labour regulation in Francophone West Africa, 2010-2020

Note. The EPL rank measures how protective/rigid is the employment law; it is from the World Bank Doing Business (2009) based on in-form hiring, hours, and redundancy regulations. The country with the least protective/rigid code is ranked No. 1, and the country with the most protective code is ranked 181. Financial fines and criminal penalties are for violation of minimum wage regulations as computed in Kanbur and Ronconi (Reference Kanbur and Ronconi2018).

Labour inspection resources increased during the last decade in most countries in the region. Several inspection agencies acquired computers and vehicles (US DOL 2022), and the average number of labour inspectors per 100,000 workers rose from two in 2011 to three in 2020. Furthermore, the productivity of inspectors increased substantially: an average of 27 firms per 100,000 workers was inspected per year in 2020, a figure almost three times higher than in 2011. Despite these improvements, inspection resources and activities are still quite low compared to other regions in the world. This situation has been stressed in various reports produced by the International Labour Organization and the US Department of Labor.

Less clear is why this happens. A common argument is that governments in Africa lack resources (ILO 2011). We speculate that the low level of tax revenue and public resources in the region surely plays a role, but it does not seem to be the only, or main, cause. In Francophone West African countries, it is neither difficult nor expensive to find and penalise employers who violated the labour code. Furthermore, why do labour inspectors in the region inspect about 10 times fewer firms compared to their colleagues in the rest of the world? We speculate there are few incentives to make enforcement more effective. We return to this issue below.

Penalty schedules for labour law violations vary widely across countries and their legal frameworks. In view of the sources of data available, we focus on penalties for violations of regulations containing wage provisions. We construct a measure of penalties specified in the law in the event of non-compliance with the minimum wage (Kanbur and Ronconi Reference Kanbur and Ronconi2018). Column (2) in Table 1 shows that the average financial fine in case of violation of the minimum wage is around USD 100 or less in all countries in the region, except for Senegal, where it reaches more than USD 800. This is still substantially less compared to the average financial fine in the world which equals USD 1,200. In the region, however, 44% of countries stipulate imprisonment in case of minimum wage violation, while in the rest of the world, approximately 20% of countries do so. Finally, column (4) shows that in two countries, Côte d’Ivoire and Togo, labour inspectors do not have established mechanisms to assess civil penalties in case of finding any labour violation. According to deterrence theory, higher penalties deter employers from violating the labour code since they increase the costs of doing so.

Qualitative evidence

Socio-demographic characteristics of key informants

The ages of the informal employees who participated in the interviews ranged from 23 to 57 years. Among the twenty-one informal employees interviewed in the first group, eleven had some tertiary level education, four had secondary education level, and six primary schools. Among those interviewed in the second group, eighteen had primary education, and two had no formal education.

Though informal employers represented differences in their type of activity, their characteristics were almost the same. In fact, all the informal employers who participated in the interviews owned small businesses with 3 to 30 employees. They all report paying salaries above the minimum wage, but none provided paid vacations or social security benefits to their employees.Footnote 13

Finally, all the labour inspectors we interviewed have a master’s degree – since it is a requisite to hold the job – and have passed the competitive exam of the National School of Administration. In their opinion, the labour inspectorate is very strict in its selection process, and it is impossible to enter through political connections. More socio-demographic characteristics of KIs are in the appendix.

Labour inspection challenges in the informal sector

In Senegal, labour inspections are expected to play a vital role in ensuring effective labour law enforcement and compliance by focusing on three key functions: providing information and education on the provisions of labour laws, preventing violations of the labour laws by providing advice and warnings, and sanctioning violations.

According to the Directorate of Labor Statistics and Studies report of 2021, there are 17 local labour inspectorates distributed all over the country.Footnote 14 A total of 99 ‘control agents’Footnote 15 work in those agencies: 42 are labour inspectors and 57 are labour controllers.Footnote 16 They inspected 2,918 firms during 2021, reaching 55,500 workers. That is, on average, a labour inspector in Senegal inspected only 30 enterprises in 2021, with approximately 19 employees each. Of the 2,918 firms inspected, there were 1,223 summonses (42%), 1,021 oral observations (35%), 465 observation letters (16%), 118 cases of no action (4%), 61 formal notices (2%), 4 infringement notices, 1 site closure, and 25 cases not documented (1%) (DSTE 2022). The very low number of inspections conducted per inspector/year appears to be in part because inspectors spend most of the time doing labour administration chores, a situation that has already been clearly pointed out by Auvergnon et al (Reference Auvergnon, Laviolette and Oumarou2007).Footnote 17

All six interviewed labour inspectors reported that the first time they visit an establishment, they adopt a pedagogical approach by providing information and education regarding the provisions of labour laws. Non-monetary sanctions are typically used as a last resort when a compliance notice has been ignored. Depending on the nature of the violation, the sanction may range from a letter of observation or formal notice to a procès-verbal of infraction submitted to the public prosecutor. However, fines (i.e. monetary sanctions) are excluded. C2 reported, ‘In case of non-compliance, a letter of observation is issued to highlight the various failures and suggest corrective measures. If the employer fails to correct the various deficiencies, a formal notice is issued before preparing the procès-verbal of violation to be transmitted to the Public Prosecutor’. C2 stated,

When we notice a situation of non-compliance, we usually summon the employer to our offices. Following this, a reminder of the obligations is made and a deadline for regularisation is set. During these meetings, we proceed to a pedagogy of awakening by reminding the risks linked to the non-declaration. However, the laws in force do not allow for fines to be imposed now, which is a considerable hindrance to the action of the inspections.

The size of the informal sector is a major challenge in Senegal, but despite that, labour inspections target mainly formal firms. This was pointed out by C3, ‘Labor inspections focus particularly on registered workers and enterprises, although targeted inspections are sometimes conducted in the informal sector, especially in the area of occupational health and safety’. The difficulty/unwillingness of reaching the informal sector is reflected in the annual reports released by the Directorate of Labor Statistics and Studies. In 2021, the labour inspectorate detected a 35.7% rate of non-compliance with health insurance and a 27.6% rate of non-compliance with social security registration. Both figures are substantially smaller than the actual rate of non-compliance, which are estimated at 85.7% and 84.2%, respectively (DSTE 2022).Footnote 18

Golub et al (Reference Golub and Mbaye2015) also point out that, while officials from the Senegalese Directorate of Labor Inspection and Social Security claim to oversee the informal sector, the bulk of inspections and disputes concern formal sector firms and workers. Samba (Reference Samba2021, 241) goes even further and argues that monitoring labour standards in the informal economy is ‘not yet on the agenda’.

Another piece of indirect evidence that suggests that inspectors do not visit informal firms is the fact that the average size of the inspected establishments is 19 employees. This is a relatively high figure in the Senegal context, where most establishments usually have between two and five employees. A similar situation occurs in Burkina Faso, where the average size of the inspected establishments is 21.5 employees (MFPTPS 2021). Further to this, many businesses prefer to operate informally in the hope of avoiding paying taxes and being inspected since inspection generally covers the formal sector. C1 said,

The majority of the enterprises we inspect are in a hybrid situation. In reality, they pretend to be in the informal sector while they are registered with the NINEA and the Registry of Trade. Footnote 19 Additionally, they can have all of the components of a formal business structure: invoices, cash registers, work clothes, and sometimes an accountant is available as well.

This situation also indicates that there is a certain lack of incentives for formalisation that deters employers from operating in the formal sector and enrolling in social security schemes.Footnote 20

In this regard, employees interviewed in the first group were requested to indicate their level of agreement with the statement regarding the conduct of labour inspections in the informal sector. The results indicate that most employees (18 out of 21 or 85.6%) strongly agree or agree that labour inspectors almost never inspect informal businesses. We did not ask the same question to employees interviewed in the second group because very few (2 out of 20) knew about the existence of labour inspectors.Footnote 21

Finally, all the above figures refer to the urban sector. In Senegal, 42% of the population resides in rural areas, where most workers are subsistence farmers, and the informal economy is even more prevalent. C6 reported: ‘labour inspectors usually cover urban areas; we go to the rural sector, but only to inspect large agricultural firms’. This is in part because of lack of means of transportation or funding to cover the costs (Auvergnon et al Reference Auvergnon, Laviolette and Oumarou2011).

Awareness of labour legislation in the informal sector

We find that informal employees have inadequate awareness of their rights. Almost half (19 out of the 41) informal employees report knowing what the minimum wage is, but only two (less than 5%) were able to indicate the monetary amount of the monthly wage to which they are entitled.

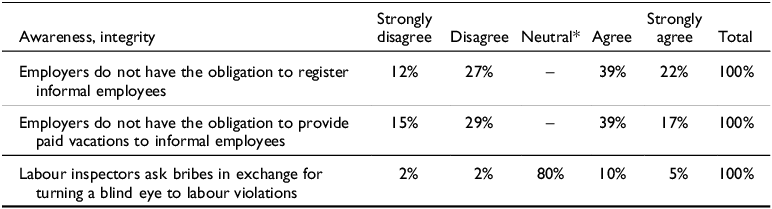

To assess their level of awareness regarding other legally mandated labour and social security benefits, employees were further requested to indicate their level of agreement with two false statements related to the labour legislation: 61% of respondents agree (or strongly agree) that employers do not have the obligation to register employees working under informal conditions, and 56% agree that employers do not have the obligation to provide paid vacations to employees working under informal conditions (see Table 2). This situation indicates that many informal employees lack awareness of their rights, leaving more room for non-compliance when dealing with exploitative employers. The low levels of awareness are substantial considering that we interviewed a relatively highly educated sample of workers, that is, those who are more likely to be informed about their rights.

Table 2. Awareness of labour legislation among informal employees and their opinion about the integrity of labour inspectors, Senegal

Note. The figures are based on 41 interviews conducted with informal employees. * Neutral includes ‘I do not know’ or ‘I do not have an opinion about this’.

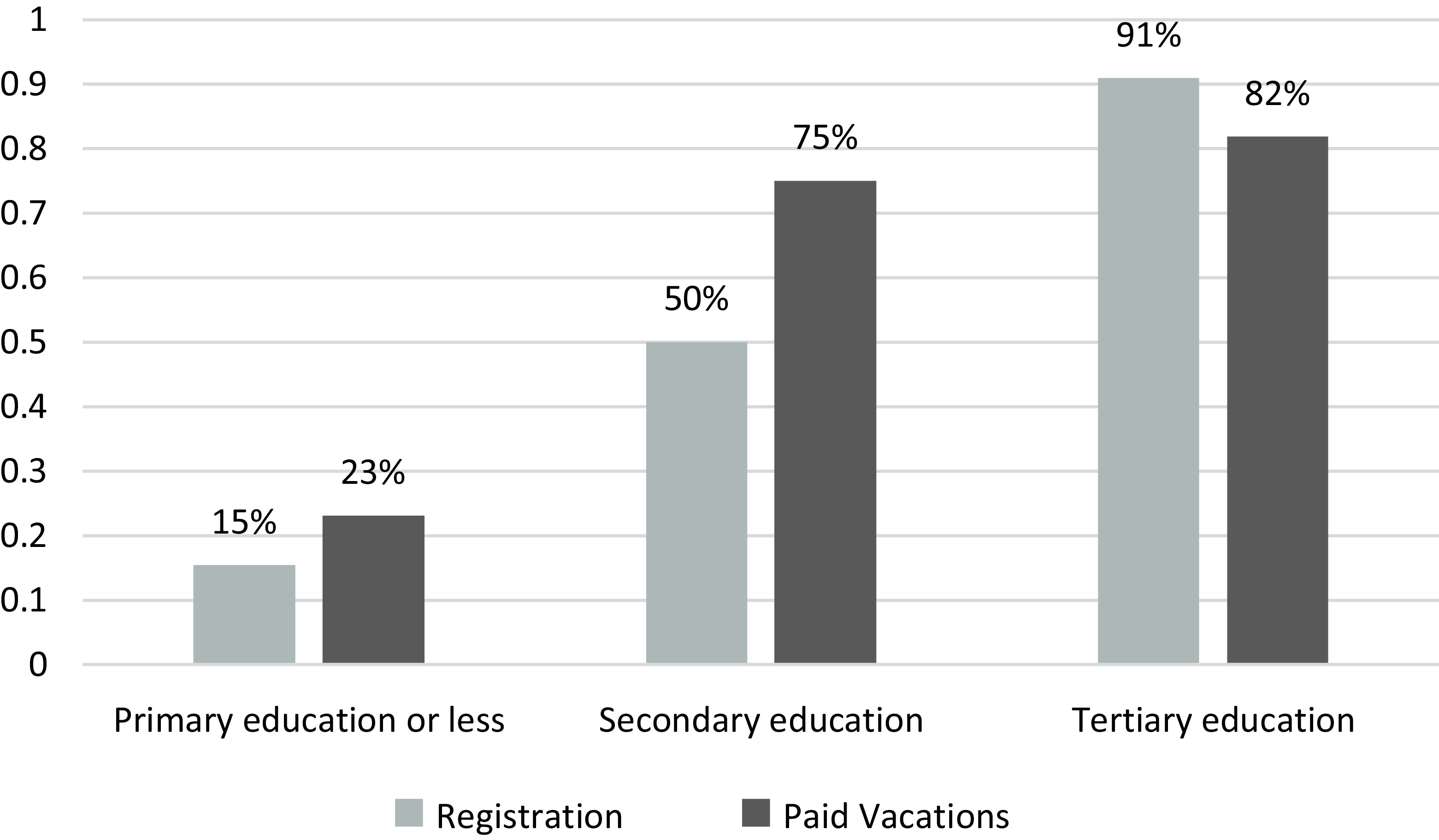

Figure 1 illustrates the positive correlation between education and awareness of labour rights. Among employees with primary education or less, only 15% knew that informal workers must be registered, and 23% knew that they are entitled to paid vacations. But, among informal employees with tertiary education, 91% and 82% confirmed that employers are required to register informal employees and grant them paid vacations. Not surprisingly, employees are more likely to know their rights, the higher their level of education.

Figure 1. Workers’ education and awareness of their rights (%).

Source: Own elaboration based on interviews with informal employees.

It should be noted, however, that awareness of labour rights does not necessarily translate into formal employment. In fact, despite knowing their labour rights, the interviewed employees continue to work under informal conditions. Although this may seem contradictory, it can be explained by the fact that labour demand in the formal private sector (especially large manufacturing firms) is stagnating and the public sector is not recruiting, making it difficult to find formal jobs (Gueye and Mbaye Reference Gueye and Mbaye2018).

As found in other countries and continents (Von Richthofen Reference Von Richthofen2002; Danziger Reference Danziger2010; Badaoui and Walsh Reference Badaoui and Walsh2022), we find that in Senegal, the lack of awareness of labour rights is exacerbated by the reluctance of informal employees to complain because of fear of losing their jobs. For example, when we asked informal employees: ‘Did you ever denounce your employer for lack of compliance with labour law?’ We received responses such as ‘I’m afraid of the consequences. If my employer finds out, he could dismiss me’ (A36); ‘I’m one of those employees who can’t make a claim. We have a verbal contract … there’s also the risk of being dismissed very easily’ (A39). Labour inspectors agree. C4 shared, ‘We receive very few complaints because workers are afraid to denounce their employer at the risk of losing their job. In some cases, however, we can have two enterprises controlled following a telephone report’.

Among the 41 interviewed informal employees, only three denounced her/his employer for non-compliance with labour laws. A19 shared, ‘I was recruited by my employer on the basis of a contract, which was not respected, as well as several broken promises. I filed a complaint with the labour court, and the case is pending at the moment’.Footnote 22 The other two cases were due to lack of salary payment. A30 mentioned that ‘I made a complaint to the police, which finally resulted in an out-of-court settlement’, while A24 expressed that ‘We went to the Labour Inspectorate, which helped us to recover our back pay’.

That said, the survey findings indicate that most informal employees were not satisfied with the way labour inspection is performed in Senegal. An employee said, ‘I have been in this company for 5 years. But I have never been interviewed by a labour inspector to discuss the problems I face in my workplace. When the inspector came, he only met with the management’ (A11). In this regard, employees and employers were also requested to indicate their level of agreement with a statement regarding the integrity of labour inspectors. The findings reveal that most employees as well as employers remained neutral on the statement that labour inspectors ask bribes in exchange for turning a blind eye to labour violations. Neutral means that they answer ‘I do not know’ or ‘I do not have an opinion about this’.Footnote 23

Analysis of main findings

There is little debate among social scientists that Francophone West African countries usually have the most protective/rigid labour codes and the lowest share of workers with access to labour benefits. There is, however, much debate about the causal links between these two variables. On the one hand, neoclassical labour economists consider that EPL causes poor outcomes since they assume a competitive labour market wherein each individual firm is a wage-taker. The narrative is that the introduction of protective/stringent EPL increases the cost of labour more than workers’ productivity, and hence, the labour demand (of compliers) falls below its market-clearing level. Those individuals who became unemployed engaged in informal unregulated activities at low pay to survive. These people, combined with those who work as employees for employers who simply ignore the labour law, produce the large informal sector. On the other hand, institutional labour economists consider that the main problem is the lack of enforcement of EPL. They assume that employers have substantial wage-setting power and that EPL can restore efficiency and reduce workers’ exploitation. But, according to their narrative, key actors (such as powerful elites) may accept the formal introduction of EPL, but not its effective implementation.

There are, of course, intermediate positions such as the one presented in the World Bank’s 2013 Jobs Report. But the point we want to stress is that without including enforcement into the analysis, it is not possible to test which of the alternative hypotheses has more explanatory power, and hence, which is the most adequate way to regulate the labour market. In the previous section, we contributed towards that objective by providing descriptive evidence of enforcement in Senegal and, to a lesser extent, the region. This is a necessary step towards producing evidence-based policy recommendations.

The data we gathered show that: first, most informal employees are not aware of their rights. They do not know that the employer has the obligation to register them and to make contributions to the social security system. Most of them do not know the level of the minimum wage, and some do not even know about its existence. Awareness of the right to paid vacations is slightly higher, although far from complete. Second, when we asked the sub-group of informal employees who know that they are not receiving legally mandated benefits, about denouncing the employer, most responded negatively, explaining that they fear losing their jobs and not finding something else.

The combination of these two factors, that is, employees’ lack of awareness of their rights and fear of retaliation, underscores the importance of the labour inspectorate. This is because an alternative means of enforcement – such as employees going to the judiciary, which is the main form of individual private enforcement – is unlikely to work effectively when workers do not know their rights or are afraid of denouncing their unlawful employers.

Despite its importance, the labour inspectorate in Senegal focuses largely on the formal sector (i.e., where labour violations are less prevalent). None of the informal workers we interviewed have ever been actively approached and interviewed by a labour inspector, and only two worked in a firm that was once inspected. Many workers knew about the existence of the labour inspectorate and consider that inspectors do not visit informal firms. Similarly, we could not find any informal employer who has been inspected by a labour inspector. The opinions of informal employers we interviewed are like those of informal employees: labour inspectors do not visit the informal economy.

Furthermore, labour inspectors do not appear to contribute much to any reduction of labour law violations in Senegal. The data we collected suggest that there are two main reasons for this. First, labour inspectors usually focus on large and formal firms. Because labour violations overwhelmingly occur in small informal firms, then, the labour inspectorate is not visiting those places where the most vulnerable workers are located. Second, labour inspectors usually follow a purely pedagogical approach that could be insufficient to significantly raise compliance. These findings are at odds with the idea that enforcement problems can be largely solved by injecting more funds into the labour inspectorate. The evidence suggests that funds have not been used efficiently to protect the most vulnerable workers. We speculate that the critical aspect is to give political voice and power to low-skilled informal workers.

On the positive side, political manipulation to enter the inspectorate appears to be basically non-existent in Senegal. They enter after passing an exam, making the selection process relatively meritocratic and transparent. Furthermore, the anecdotal evidence we were able to collect suggests that the labour inspectorate is usually not captured by large businesses, although some examples suggest the existence of important exceptions.Footnote 24

Finally, we did not obtain much information about the extent of petty corruption in the labour inspectorate. This is in part because almost none of the workers and employers we interviewed had first-hand experience with labour inspectors. When we asked them what they heard about petty corruption from other people, the answer usually was that they did not know anything. We speculate, however, that most labour inspectors do not ask bribes in Senegal because they tend to visit formal firms with few violations and because they do not impose monetary fines, although this is very tentative and deserves more research. Again, we speculate that the main problem is the lack of voice and power of informal workers rather than a principal-agent problem between policymakers and inspectors.

Conclusion

This paper provides novel descriptive evidence about enforcement of labour regulation in Senegal and, to a lower extent, in the other eight Francophone West African countries. We find, first, that workers, and particularly those with low levels of education, are not aware of their rights, reducing the effectiveness of private enforcement. Second, labour inspection resources and activities are quite limited in the region, and the scarce resources tend to focus on large urban formal firms, where labour violations are lower, leaving most informal firms that do not comply with regulations flying under the radar. That is, both private and public enforcement institutions are not properly taking care of the most vulnerable workers in the region.Footnote 25

We conclude with a policy-oriented thought. Labour regulation is a contested subject. Social scientists have attempted to contribute to the debate by estimating a causal effect of labour regulation on various outcomes (Deakin et al Reference Deakin, Malmberg and Sarkar2014). But because of a lack of enforcement data and local knowledge, social scientists have regularly assumed that in-form regulations are an adequate proxy for effective regulations in LMIC (Botero et al Reference Botero, Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer2004; Djankov and Ramalho Reference Djankov and Ramalho2009). This paper provides objective data showing that, in Francophone West Africa, that is quite an inaccurate assumption. Graham (Reference Graham1954), a labour inspector who worked in the less developed world, made a similar point seventy years ago. Countries in the region have – compared with other countries in the world – quite protective/stringent labour codes, yet they also have the lowest levels of enforcement.

Such a combination of protective/stringent labour codes with little enforcement appears puzzling, opening interesting avenues for future research, particularly in the field of political economy. Why does a society choose to have in-form protection and, at the same time, turn a blind eye to non-compliance? What is the influence of domestic and external factors, such as electoral politics and the interference of international organisations? Do colonial legacies and legal traditions play a major role? Beyond intellectual curiosity, the topic is important from a public policy perspective. As discussed above, labour market policies and institutions are not properly taking care of the most vulnerable workers in the region.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/elr.2024.12.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mamadou Thiam, Alioune Tall, two anonymous referees, and colleagues at the Partnership for Economic Policy (PEP) for their useful comments.

Funding statement

No funding to report for this submission.

Competing interests

There are no competing interests.

Thierno Malick Diallo is Lecturer at Gaston Berger University, Saint-Louis, Senegal, and researcher at PEP. His research interests include Labour Economics, Education, and Rural Development.

Lucas Ronconi is Professor of Economics at University of San Martin, Buenos Aires and CONICET, Argentina; and non-resident research fellow at IZA and PEP. His research interests include Development, Labour Economics, and Political Economy.