Introduction

Defining complex depression

Approximately 90,000 people enter psychological therapy in IAPT services across England every month, many of them affected by depressive disorders (IAPT Executive Summary, 2016). A proportion of clinical presentations within mental health services has always been complex. Even if that proportion is unchanged, IAPT has made psychological therapies more available and it is now a much larger number of patients (Clark, Reference Clark2011). Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) therapists, particularly those working at Step 3, are working with complex cases – for example, patients with trauma histories and personality problems, and a proportion are known not to respond to disorder-specific protocols (Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Wingrove and Moran2015).

NICE guidance for the treatment of complex depression identifies a group of clients who are expected to receive treatment at Step 4 in the stepped care system:

‘Complex depression includes depression that shows an inadequate response to multiple treatments, is complicated by psychotic symptoms, and/or is associated with significant psychiatric comorbidity or psychosocial factors’ [NICE Clinical Guideline CG90 (2009)]

Most therapists would expect a patient with depression who also manifests psychosis, other co-morbidities, psychosocial stress and/or an inadequate response to previous treatments to be a challenging case. Such cases would typically be described as complex but the above guidance does not really define what complexity is. Nor does it distinguish personally demanding or technically difficult cases from those that are genuinely complex.

Arguably, the absence of an accepted definition of complexity has led to its over-use in some circumstances. When the concept is over-used there are various consequences: firstly, complex can become a post-hoc attribution for treatment failures (Tarrier and Johnson, Reference Tarrier and Johnson2015). It produces an empty explanation why CBT was ineffective with particular cases, possibly concealing a lack of real understanding why treatment did not work. Treatment failures may or may not be attributable to client complexity, but this can only be established in prospective clinical tests, not post-hoc rationalizations. Secondly, complex becomes a proxy or collective term for a range of depressive features that have precise clinical meanings: for example, severe, high risk, early-onset, treatment-resistant, recurrent, chronic/persistent (Garland, Reference Garland, Tarrier and Johnson2015). These can create difficulties for therapists and clients but they are not necessarily complicated, depending on how complexity is defined. Thirdly, it can be used to justify drift from evidence-based protocols on the assumption that complex cases are unlikely to respond to standardized treatments (Waller and Turner, Reference Waller and Turner2016). The imprecise meaning or over-use of complexity has raised concerns that therapists deviate unnecessarily from treatment protocols when faced with what they appraise to be complex cases, whether or not true complexity is present.

We propose that complexity is a valid clinical construct that can be clearly defined and is not based on post-hoc rationalizations or imprecise clinical terms.

Complexity results from interactions of biological, psychological and social factors that create barriers to treatment, challenge therapeutic alliances and modify the usual maintenance of a disorder.

Simple systems have only a few moving parts and generally behave in predictable ways, whereas complex systems have multiple moving parts and sometimes behave unpredictably. Real-life challenges often have multiple parts woven together, which Rittel and Webber (Reference Rittel and Webber1973) called ‘wicked problems’ to describe the messiness of these situations. This is our starting point in considering how complexity manifests in depression. When the NICE definition is reconsidered, a client with depression who also manifests psychosis, other co-morbidities, psychosocial stress and/or an inadequate response to previous treatments can be seen to have ‘multiple moving parts’. The treating therapist is not only presented with depression – there are several other factors to consider. This would not be a major issue if these were separate independent difficulties. For example if psychosis, other co-morbidities, psychosocial stress and/or an inadequate response to previous treatments had no bearing on the maintenance or treatment of depression, then there might be little or no need for this article. The client's depression could be treated like any other case using cognitive therapy (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979) or behavioural activation (Martell et al., Reference Martell, Dimidjian and Herman-Dunn2010).

If we adopt a pragmatic criterion to use the simplest possible intervention that has a good probability of being effective, there may be cases with multiple moving parts that nevertheless respond to disorder-specific protocols. There are good reasons to take this view seriously. For example, consider a recent randomized controlled trial of CBT for moderate/severe depression (DeRubeis et al., Reference DeRubeis, Hollon, Amsterdam, Shelton, Young and Salomon2005). Approximately 60% of patients in the CBT arm responded to treatment, which is the usual level of response for major depression. Across the whole trial, 72% of patients had Axis I co-morbidity (mostly anxiety disorders) and 48% had Axis II co-morbidity. Co-morbidities were not directly treated yet therapy was still effective. We can choose to focus on the positive aspects of these findings: 60% responded without specifically attending to other disorders. Or we can choose to focus on the negative aspect: 40% did not respond and now need further treatment. ‘Non-depression’ factors, such as co-morbidities, do not necessarily complicate depression and prevent disorder-specific protocols from working. However, some non-depression factors do create complications and make it less likely that these treatments will be effective. For example, clients with co-morbid social anxiety disorder were less likely to respond to treatment in this trial.

A balanced view is that both propositions are true. Sometimes non-depression factors are not complications; they co-exist with depression and either benefit indirectly from its treatment or are unaffected by it. In other situations non-depression factors are complications; they create barriers to treatment, challenge therapeutic alliances and complicate the usual maintenance of the disorder. In the first case disorder-specific protocols should proceed as usual – which is what we envisage at Step 3. In the second case, treatment needs some kind of adjustment or adaptation, particularly if disorder-specific protocols have not been effective – this is what we envisage at Step 4.

Biopsychosocial factors

We have approached this question pragmatically and empirically by recording and mapping the non-depression features of successive depression cases over several years of clinical work. The result is presented in Table 1. We have found that non-depression factors tend to fall into biological, psychological and social categories and Table 1 lists the most common factors. The examples listed are not exhaustive or exclusive; rather they are representative of common biopsychosocial factors. They vary in their mutability with some more amenable to change than others. Depending on the service and case mix, there may be particular biological, psychological and social factors not listed here and therapists are encouraged to extend the complexity map to include factors that present in their particular service.

Table 1. Common biopsychosocial complexity factors associated with major depression

The key point is this: these factors are not features or symptoms of the major depressive episode. They are not part of the mood disorder but they have the potential to co-occur and interact with it and their presence may or may not have a complicating effect. This contrasts with depressive sub-types such as severe, high risk, early-onset, treatment-resistant, recurrent, chronic/persistent, etc. These are features of the mood disorder. They can result in difficult technical and personal challenges but they are not necessarily complications with multiple moving parts.

In clinical practice, we use a diagrammatic map of these factors, shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Biopsychosocial map of complexity factors associated with major depression

At the start of treatment the biopsychosocial factors present for any particular case are identified, mapped and circled. Others are added if they are discovered later in treatment. The explicitness of this process helps with assessment, formulation and treatment planning. However, the number of biopsychosocial factors is not a sensitive measure of complexity, although it is a good indicator of cases that warrant further scrutiny. The reason for this is that some biopsychosocial factors co-exist with depression but do not create complications (Tarrier and Johnson, Reference Tarrier and Johnson2015). What matters is identifying those factors that interact with depression in a complicating way, even if they are few in number. Complexity arises when these interactions provoke unpredictable or unusual effects and we propose that there are four main types of problem that can result:

-

1. Access – complexity factors can create barriers to treatment

For example, therapy is likely be more complicated with a patient with minimal spoken English if an interpreter is unavailable; a physically disabled patient who is unable to travel to clinic may be restricted to telephone or Skype sessions if their therapist is not supported to make home visits; a homeless person may not be allowed to self-refer if they are not registered with a general practitioner. Being a non-English speaker, disabled or homeless is not part of the depressive disorder – but any of these factors have the potential to interact with depression to complicate access to treatment, depending on the responsiveness of the service and therapist.

-

2. Readiness – complexity factors can delay the patient's readiness for treatment

For example, a patient with co-morbid depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may need a period of stabilization before they are able to tolerate regular therapy sessions; a depressed adolescent may not be developmentally ready to deal with memories of sexual abuse, but still need help to improve their mood; a patient with on-going life stress such as a court case, severe ill-health or a benefits claim may be pre-occupied with their circumstances and find it difficult to focus on overcoming depression.

-

3. Alliance – complexity factors can interfere with the development of a strong therapeutic alliance

For example, a depressed patient with paranoid tendencies may not be sufficiently trusting to form a personal alliance with their therapist; a patient with an unhelpful previous experience of CBT could insist that their treatment does not involve certain techniques; a patient with personality problems might enter a course of CBT to demonstrate to others it will not be effective – this might not be normal pessimism; it could be serving an interpersonal function to remain in a helpless or dependent position.

-

4. Maintenance – complexity factors can modify the usual maintenance of a disorder and require a non-standard change process

For example, a patient with highly chronic depression may be anxious about improvement because if they recover they could experience intense regret about time lost; a patient with depression and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) may be depressed about a feared future, not past losses; a patient with depression and PTSD may be depressed by appraisals of traumatic memories, but the memories are dissociated and difficult to access. The usual maintenance of depression is modified, altered or subtly complicated by its interaction with non-depression factors – and this could complicate the usual change process within an established protocol.

Viewed from this perspective, complexity results from interactions between depression and biopsychosocial factors: the greater their impact on access, readiness, alliance or maintenance, the greater the complexity. Complexity is therefore a spectrum across levels of stepped care, not a discrete client group, with clients varying how much these types of factors interact and create complications. Many of the above examples will present in primary and secondary services, not just specialist services, and some are highly mutable – they present relatively minor complications that can be overcome quite easily. Others are much more difficult to accommodate and if complications are not accommodated – even minor ones – this can have a major effect on treatment access, process and outcome.

Step 3: disorder-specific protocols

Complex cases can and do respond to disorder-specific CBT protocols and at Step 3 these should be the first-line intervention. However, treatment should be delivered responsively with therapists paying attention to factors that could complicate progress without switching focus between them on a regular basis. Regular switching can result in therapy becoming diffuse and disorganized. It can also mean that no single problem receives the dose of treatment needed for it to change in a sustained way.

Case illustration: Frank

Frank presented with a 19-year history of panic disorder with agoraphobia, GAD, social anxiety and depression. He was aged 44 and married with a grown-up son. He had developed panic attacks in his mid-twenties with no previous mental health or developmental problems. He started avoiding situations out of fear he would have further panic attacks. His avoidance increased and he eventually lost his job. Frank retreated from normal life, became increasingly worried and pre-occupied about panicking and being seen by others. As his negative affect increased (e.g. anxiety, embarrassment, shame) he became more avoidant and his positive affect decreased. His motivation to find other work and maintain a social life gradually became suppressed. Anxious avoidance interacted with depressive withdrawal and Frank became reclusive: within a year of losing his job he rarely left his house and had only occasionally done so in the previous 18 years. Prior to his referral Frank had received six courses of counselling, clinical psychology or psychotherapy. These had produced minimal benefit.

Frank was a challenging case because of multiple co-morbidities, long-term chronicity and resistance to prior treatments. Figure 1 depicts the biopsychosocial factors associated with Frank's depression. The question is: were these factors complications? The social and work factors were not really complications: his lack of social life and unemployment were a consequence of persistent depression and they did not directly affect his access to treatment, readiness for it, or capacity to form a good working alliance. However, the four co-morbid anxiety disorders were a potential source of complexity: panic disorder, agoraphobia, social anxiety and GAD. In spite of the apparent complexity, Frank's therapist proposed a simple strategy of focusing consistently on overcoming his agoraphobia, nested within desired life-goals to help sustain Frank's motivation. Frank and his therapist were aware of the potential influence of panic, social anxiety and GAD but made overcoming agoraphobic avoidance the priority. It was hoped that these behavioural changes would also have an activating effect towards desired goals, creating positive reinforcement as indicated within behavioural activation (Martell et al, Reference Martell, Dimidjian and Herman-Dunn2010). This iterative process was approached through three recurring steps:

-

(1) Establish concrete approach goals: i.e. Frank's desires of how he would like to live;

-

(2) Conduct exposure to feared situations while increasing behavioural activation towards desired goals;

-

(3) Reflect on the emotional and interpersonal consequences of engaging in new behaviours.

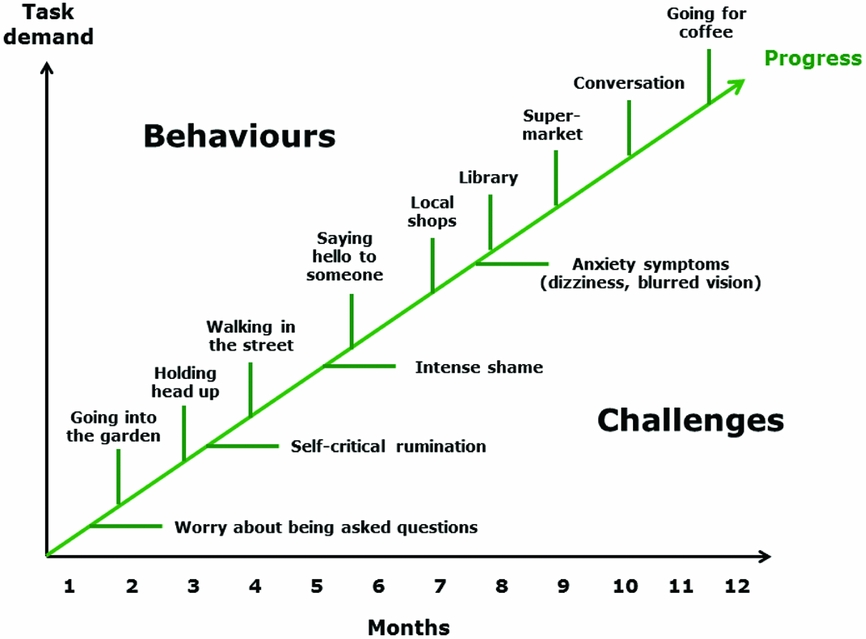

Frank generated four approach goals and these formed a natural hierarchy: (a) go out of his house without fear; (b) go out for a coffee or meal; (c) train to be a painter/decorator; (d) get a job as a painter/decorator. Figure 2 summarizes the behavioural changes across the first phase of Frank's therapy, showing the graded tasks that he approached at each stage. A slow pace was established with lots of repetition of the target behaviours. The aim was to conduct full and thorough exposure to feared situations and to only move onto the next step when the last one had become comfortable, not just tolerable. The first stage focused on Frank stepping a few yards out of his front door into his garden, then holding his head high when he did this, then walking in the local street, and so on.

Figure 2. Frank's progress in the first phase of therapy

As might be expected, at various points progress was slowed by barriers to change that at the time Frank felt were insurmountable, for example, worry about being stopped and asked questions, self-critical rumination, intense shame and severe anxiety symptoms. The strategy was to attend to these factors if they created a block on progress, doing sufficient work on them to enable the change process to continue. Using a disorder-specific strategy, it is important to remain aware of potential interactions with other complexity factors just as Frank and his therapist did. Their focus only switched if another factor had a limiting effect on the main target and created a block on progress. For example, at various points worry, rumination and shame all needed attention because they were limiting further behavioural change. Therapy was still tethered to behavioural change, but these other factors were given time-limited attention to overcome their limiting effects. Having received the attention they needed, this had a consolidating effect on the primary target and treatment then returned to focus directly on it.

The principles underlying the disorder-specific approach can be summarized as follows:

-

(i) Tether to a primary target (A) and keep it the main priority;

-

(ii) Monitor the influence of, and effects on, other factors;

-

(iii) If another factor (B) limits progress on A, give B time-limited attention;

-

(iv) Attend only to those aspects of B that are limiting progress on A;

-

(v) Return the focus to A once those aspects of B have been resolved;

-

(vi) Review progress on A after a sustained dose of treatment has been delivered (usually around 5–6 sessions);

-

(vii) Only change the primary target:

-

(a) When A is resolved and other problems require further attention;

-

(b) If limited progress has been made on A in spite of targeting it in a consistent way.

-

The evidence base in CBT for major depression suggests that this strategy will be effective most of the time because disorder-specific treatments have trans-diagnostic effects: co-morbid disorders are often interdependent and mutually reinforcing. This is a potential source of complexity but it can mean that not all disorders need direct treatment. Assuming there are sympathetic links between disorders, a number of problems will improve through trans-diagnostic and indirect effects (DeRubeis et al., Reference DeRubeis, Hollon, Amsterdam, Shelton, Young and Salomon2005). In this context sympathetic means that A improves when B improves, and A worsens when B worsens. For example, worry might not need separate treatment if changes in rumination indirectly improve the worry process. Consequently, most cases with multiple problems do not need complicated treatment. Co-morbidity is not necessarily complicated, depending on the interactions between the disorders. When problems are sympathetically linked it may not matter what the primary target is, as long as it is manageable and agreed collaboratively. There can be multiple paths to recovery: if A is targeted B improves, and if B is targeted A improves. What matters is tethering to a primary target and monitoring the influence of, and effects on, other problems.

This is a good summary of Frank's treatment. Frank's depression was challenging and difficult to change because of its chronicity and stuckness. Progress was slow. It took Frank two years to achieve his goal of going to college. After three years he was looking for work, functioning well and managing anxiety and depression symptoms that had reduced to a moderate level. However, neither Frank's depression nor its treatment was particularly complicated; progress was difficult but not complex. Although there were multiple co-morbidities the disorders were sympathetically linked. Overcoming agoraphobic avoidance had a simultaneously activating effect on his depression and these changes had a trans-diagnostic effect on his other problems.

Step 4: individualized formulation

The disorder-specific strategy for Step 3 cases will be effective most of the time, but not all of the time. The reason for this is that multiple factors are not always sympathetically linked: sometimes B worsens when A improves, and A worsens when B improves. This suggests antagonistic rather than sympathetic links. In this scenario, change in one area will not necessarily have a trans-diagnostic or helpful effect on other problems. There can also be unstable relationships between factors; in other words, the relationship between A and B is not constant. Some multiple parts are not just interacting; they are changing unpredictably over time. They form a moving target and this makes it difficult to maintain a consistent treatment focus. In Step 3 there are multiple paths to recovery and it may not always matter what the primary target is. In Step 4 the path to recovery is much harder to find. Whichever target is chosen it is difficult to produce change; other factors have a limiting effect or deteriorate when the primary target improves. Consequently, working at Step 4 requires careful navigation: finding a way through densely inter-woven difficulties in spite of cul-de-sacs, wrong turns and dead ends. A good case formulation is essential to map and explore the territory and therapists need to be tenacious, flexible and hopeful, viewing all set-backs as learning opportunities.

Working at Step 4 requires an explicit formulation of the multiple factors interacting with the depression. We propose that this is the main difference between Step 3 and Step 4. At Step 3 the disorder-specific strategy is to tether to a primary target and pay attention to other factors on a needs-led basis. Working simply and pragmatically, there is no need to formulate the whole case if changes in the primary target have a trans-diagnostic and generalized effect. Working at Step 4, the relationship between factors is more likely to be antagonistic, unstable and unpredictable; the usual maintenance of depression is altered and the interaction of multiple factors needs to be formulated to decide how best to proceed. This does not mean providing complicated treatment. Therapy should still be simple at the point of delivery – but deciding which target and therapeutic task depends on a formulation of the multiple factors affecting the case, some of which may be contextual (outside-in), others intra-psychic (inside-out). It means careful targeting of the functional links between problems: rather than targeting A or B, the interaction of A and B is targeted. These interactions can be highly idiosyncratic and need to be approached on a case-by-case basis.

Case illustration: Jeff

At the time of his referral, Jeff was aged 48 and married with two daughters. He was a public service employee with a 20-year history of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) with recurrent major depressive episodes (MDE). Jeff had previously received three courses of CBT:

Treatment 1: CBT for OCD (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2005). Jeff received 14 sessions over a 4-month period. Due to unpredictable changes in mood and affect, it was difficult keeping the focus on OCD. During this treatment a psychiatric assessment resulted in a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder. Jeff disclosed his diagnosis to his employer, believing this was the right thing to do, and this initiated a lengthy process of occupational health assessment. The bipolar diagnosis coincided with staffing changes and Jeff was offered a new therapist who specialized in the area of unstable mood.

Treatment 2: CBT for bipolar disorder (Meyer and Hautzinger, Reference Meyer and Hautzinger2012). Jeff received 53 sessions over a 3-year period. The therapeutic dose reflected the severity of Jeff's depression, mood swings and occasional hypomanic episodes. Treatment was strongly affected by the occupational health process. Jeff was assessed by a number of medical practitioners, not all with psychiatric training. The stress and uncertainty provoked by these assessments interacted with Jeff's unstable moods and made it challenging to progress. Over an extended period there was a gradual improvement and stabilization of Jeff's mood. OCD was not the priority during this period and it was not targeted explicitly within treatment.

Treatment 3: Consolidation of CBT for bipolar disorder. Jeff received a further 23 sessions over a 2-year period to consolidate progress and help him cope with the occupational health process. In the intervening period, his employer had reacted in a risk-averse way, moving him to a less senior role within the organization. His manager informed him: ‘your mental health problems mean you cannot talk to the public’. This had a devastating effect on Jeff's self-esteem and shattered his assumptions about his employer's competence, loyalty and duty of care. It provoked extreme anger, reactivated Jeff's OCD and led to further mood de-stabilization. The context of acute occupational stress was a complicating factor because it increased uncertainty and made it difficult for Jeff to maintain a consistent treatment focus.

In spite of the benefits gained from these treatments, Jeff relapsed into moderate depression with occasional expansive moods and his OCD had also been re-activated. He was pre-occupied by anger with his employer and this was interfering with his functioning at work. Disorder-specific protocols had not had a lasting effect so an alternative approach was adopted. Jeff was offered a new therapist and subsequently received 44 sessions of CBT over a 2-year period. The strategy was firstly to map the non-depression factors that could be complicating his presentation, illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3. Biopsychosocial map of complexity factors associated with Jeff's depression

This revealed three social factors and three psychological factors. The therapist did not assume that these were complicating Jeff's mood disorder; rather, there was a process of guided discovery to find out whether or not they were having a complicating effect. There was a potential healthcare factor concerning Jeff's repeated relapses that may have reduced his confidence in CBT or the clinical service. In fact, this was not the case. Jeff reported experiencing the benefits of the previous courses of CBT but something stopped them having a sufficiently potent and lasting effect. There was a potential interpersonal factor following significant tensions between Jeff and his wife; however, they had managed to overcome these difficulties and they were no longer problematic. There was a clear and pronounced occupational factor that had a complicating effect on Jeff's depression both during and after the occupational health process.

The occupational stress interacted with three psychological factors: hypomanic moods, OCD and post-traumatic anger. Occupational stress over the previous five years had a traumatic impact on Jeff. He was not suffering from PTSD but he continued to feel ‘devastated’ by his employer's actions. They had a profoundly disruptive impact on his self-identity and Jeff felt extremely hurt and angry several years after the most stressful events had occurred. Jeff's work had been a significant and self-defining aspect of his self-identity throughout his adult life.

At Step 4 the strategy is not to deliver a disorder-specific protocol for any one of these problems. Instead, an individualized formulation is developed of the interactions between these factors, i.e. the functional links where the output of A is the input to B, and so on. At the outset of therapy a simple map is used with the main presenting problems on it and this is used to explore the interactions between them. In Jeff's case, as the map grew and became better specified there were three main benefits to having an over-arching formulation. Firstly, because Jeff's problems were inter-dependent and highly changeable the formulation helped to identify his mental state at any point and enabled reflection on how it was affecting his other difficulties. Secondly, the emerging map made it more straightforward to agree the optimal treatment focus at that point. Thirdly, by paying close attention to the interaction between Jeff's difficulties, functional links became apparent and these could then be targeted for change.

Using this approach it is important to ensure that therapy is evidence-based in two key respects: firstly, the formulation should be tested empirically through guided discovery, collaboration, behavioural experiments, etc., so that hypotheses about functional links are disconfirmed and not just assumed. Secondly, only treatment components from evidence-based protocols should be used, even if they are delivered in a novel sequence or innovative way. In Jeff's case occupational stress, depression, hypomania, OCD and post-traumatic anger were interacting in a way that complicated the usual maintenance of depression and made it harder for disorder-specific protocols to have a lasting effect.

The formulation evolved gradually over several sessions and the final version is presented in Fig. 4. Jeff's difficulties were re-triggered by continuing to work in the same organization. Memories of how he had been treated were re-activated on a daily basis and this provoked intense upset, anger and occasional rage. The anger triggered vengeful thoughts and images in which he would retaliate against his managers with extreme physical violence. A complicating factor was the unpredictable effect of those thoughts on Jeff's obsessional and hypomanic tendencies. Sometimes he would experience the thoughts as unwelcome intrusions and an OCD cycle would be triggered with inflated responsibility to prevent harm, anxiety about acting on the thoughts and then various forms of neutralization, including behavioural avoidance and thought suppression. On other occasions Jeff would experience the thoughts as liberating: they enabled him to emotionally process traumatic memories but this could also have a disinhibiting effect, leading to grandiose ideas about being powerful and dominant, resulting in elated mood and raising concerns about risks of harm to others.

Figure 4. Jeff's individualized case formulation

Jeff had learned the harmful consequences of hypomania during earlier treatments and he was wary of acting inappropriately with other people. Memories of past hypomanic behaviour were sometimes activated, leading to guilt and shame-based rumination which had the potential to depress Jeff's mood and spiral into helplessness and social disengagement. Guilt and shame also activated Jeff's felt-sense of responsibility to act dutifully as a husband, father and public servant and this had a reinforcing effect on the OCD cycle. As Fig. 4 illustrates, by mapping out the links between disorders Jeff and his therapist were able to make sense of his different mental events and mood states. The formulation helped to de-mystify and explain what Jeff otherwise experienced as ‘mental turmoil’ or ‘going mad’.

The main complication was anger simultaneously triggering an inhibiting process (OCD) and a disinhibiting process (hypomania) that produced unstable moods, internal conflict and cognitive disorganization. In this respect the maintenance of Jeff's depression was subtly different from many clinical presentations. His depressed moods had classic features such as social withdrawal, rumination and self-critical thinking. However, targeting depressed moods did not automatically improve interactions between depression, hypomania, OCD and post-traumatic anger.

Three trans-diagnostic factors also became apparent; firstly, across different mood states Jeff would often engage in unhelpful repetitive thinking. The content tended to be self-critical in the depressed mode, self-actualizing in the hypomanic mode, retaliatory in the traumatized mode and obsessional in the OCD mode. The common process was repeated dwelling on emotionally charged topics that was generally unproductive and created further distress. Secondly, Jeff's affect was unstable irrespective of which disorder was dominating his current mental state. Thirdly, across different mental states Jeff's self-identity was often uncertain and confused. There was a degree of self-identity confusion prior to treatment that had been exacerbated by the occupational health process. These trans-diagnostic factors were placed in the centre of the formulation as a reminder of higher-order processes that could be targeted in any mood state, for example, encouraging Jeff to be reflective rather than ruminative, encouraging acceptance of affect in favour of emotional avoidance, and affirming experiences in which he felt grounded in his ‘true self’.

In addition, Jeff's treatment included a series of sessions delivering exposure and response prevention (ERP) for his obsessional thoughts (McKay et al., Reference McKay, Sookman, Neziroglu, Wilhelm, Stein, Kyrios, Matthews and Veale2015). Their content was primarily based on the perceived threat of acting on his anger and harming his employer. Jeff was able to expose himself to these thoughts, tolerate the distress they provoked and gradually recognize that they were only thoughts and not intentions. The only deviation from standard protocol was monitoring for hypomania and behavioural disinhibition; this occurred in some of the early exposures. This was used to elaborate the formulation. Overall, the formulation had an integrating effect on Jeff's learning; he was able to identify which processes were active at any point and developed greater mastery in counteracting them with different cognitive and behavioural strategies. Jeff has since made a successful transition into early retirement and his treatment has ended.

Main points

In summary, there are a number of guidance points to help CBT therapists work effectively with complex cases of depression:

-

(1) Use exact terms when describing clients and try not to conflate complexity with other features of depression such as severity, risk, recurrence or chronicity. These features can create difficult personal and technical challenges for clients and therapists, but they are not necessarily complicated or complex.

-

(2) Pay attention to biological, psychological and social factors that co-occur with depression. They may not need to be formulated and targeted explicitly but some will interact with depression and ‘multiple moving parts’ can create complications, including therapy becoming diffuse, disorganized or over-complicated.

-

(3) When complications are present, use disorder-specific protocols in the first instance and deliver treatment responsively to accommodate complexity factors. Pay particular attention to factors that could affect access to treatment, patient readiness, the formation of therapeutic alliance and unusual maintenance processes.

-

(4) At Step 3, select a primary target and tether to it. Provide a sustained dose of treatment on that target and try not to switch focus regularly to other factors. If other factors limit progress give them time-limited attention and return focus to the main target when those aspects have been resolved. Therapy should be simple at the point of delivery.

-

(5) At Step 4, when disorder-specific protocols have been ineffective, develop an individualized formulation of the interactions between depression and biopsychosocial factors, including co-morbid disorders. These interactions can be highly specific to the individual case and need to be targeted carefully to enable change. Therapy should still be simple at the point of delivery – but a formulation of multiple moving parts is needed to keep it simple.

Ethical statement

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the APA. No ethical approval was needed: the treatments were delivered within routine clinical practice and the clinical cases consented for anonymized details of their therapy to be included.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge their gratitude for the contribution of colleagues at the Newcastle CBT Centre to the development of these ideas, in particular Mark Freeston, Kevin Meares and Matt Stalker. Beth Bromley provided helpful feedback on the manuscript, as did two anonymous reviewers; our thanks also to the clinical cases for allowing their treatment to be summarized and included.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Learning objectives

-

(1) To consider a range of biological, psychological and social factors that can interact with depression to complicate its maintenance and treatment.

-

(2) To reflect on adjustments that can be made at Step 3 to the delivery of disorder-specific protocols to accommodate the needs of patients with complex presentations.

-

(3) To consider ways of further adapting CBT at Step 4 for complex cases when disorder-specific protocols have not been effective.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.