Introduction

Currently, there are over 55 million people worldwide living with dementia, and the global annual cost of dementia is estimated to be US$1.3 trillion (World Health Organization, 2021). Informal care provided by family members is estimated to account for half of such annual cost, suggesting that family carers are an essential taskforce in caring for people with dementia. Although there are various positive aspects of caregiving (Yu et al., Reference Yu, Cheng and Wang2018), the psychological and physical demands of caregiving can have a significant impact on mental health among family carers. There is considerable evidence suggesting that family carers of people living with dementia are at high risk of developing anxiety and depressive symptoms (Collins and Kishita, Reference Collins and Kishita2020; Kaddour and Kishita, Reference Kaddour and Kishita2020). However, many are not able to access timely psychological support due to various barriers such as restricted mobility, lack of respite care and a shortage of skilled therapists (Alzheimer’s Society, 2014).

Currently, dementia family carers who receive the least support in the United Kingdom (UK) are those from ethnic minority groups. For example, a systematic review of studies that included UK South Asian people living with dementia could not identify a single clinical trial of an intervention in this population, either for patients or for carers (Blakemore et al., Reference Blakemore, Kenning, Mirza, Daker-White, Panagioti and Waheed2018). Barriers to accessing support in ethnic minority family carers often emerge from cultural values where caregiving is seen as a familial obligation and outside help indicates failure, leading carers to feel guilty or ashamed to seek formal support (Duran-Kiraç et al., Reference Duran-Kiraç, Uysal-Bozkir, Uittenbroek, van Hout and Broese van Groenou2021).

Self-help psychological interventions that use technology, such as internet-delivered psychotherapies, have the potential to overcome existing barriers (such as those associated with fear, stigma, and reluctance to talk to individuals outside of the family about personal problems), as these interventions require fewer interactions with healthcare professionals (Cuijpers and Schuurmans, Reference Cuijpers and Schuurmans2007). Furthermore, systematic reviews on internet-delivered, self-help, psychological interventions for people with common mental health problems suggest that such interventions are equally beneficial to traditional face-to-face interventions (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Basu, Cuijpers, Craske, McEvoy, English and Newby2018), and could potentially facilitate treatment readiness if patients require more intense face-to-face interventions at a later stage (Andersson and Titov, Reference Andersson and Titov2014).

Interest in supporting dementia family carers through internet-delivered interventions is rapidly growing, with increasing evidence suggesting that they may be beneficial in improving the well-being of family carers and offer advantages over traditional face-to-face interventions, such as reducing transportation and time barriers (Etxeberria et al., Reference Etxeberria, Salaberria and Gorostiaga2021; Naunton Morgan et al., Reference Naunton Morgan, Windle, Sharp and Lamers2022). Despite the evidence supporting the feasibility and efficacy of internet-delivered, self-help interventions for mental health problems in the general population, as well as for dementia family carers, such evidence is limited for people from ethnic minority groups. In addition, some studies report that the drop-out rate may be higher among ethnic minority individuals due to different factors, such as lower digital literacy (e.g. concerns related to confidentiality) and their level of comfort with technology as these groups are still somewhat affected by a digital divide (Ramos and Chavira, Reference Ramos and Chavira2022). Therefore, finding ways to improve experiences of internet-delivered, self-help, psychological interventions for family carers of people living with dementia from ethnic minority groups is critical for the development of interventions that are inclusive and widely accessible.

This study aimed to explore the views of family carers from ethnic minority groups and their therapists on an internet-delivered, guided, self-help psychological intervention based on acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for dementia family carers (iACT4CARERS), enhanced with additional therapist guidance. Previous studies have demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of iACT4CARERS in a sample of predominantly White dementia family carers and their therapists (Contreras et al., Reference Contreras, Van Hout, Farquhar, Gould, McCracken, Hornberger, Richmond and Kishita2021, Reference Contreras, Van Hout, Farquhar, McCracken, Gould, Hornberger, Richmond and Kishita2022; Kishita, Gould et al., Reference Kishita, Gould, Farquhar, Contreras, Van Hout, Losada, Cabrera, Hornberger, Richmond and McCracken2022). Therefore, there is a potential for iACT4CARERS to be used with dementia family carers from ethnic minority groups.

Previous reviews on internet-delivered, self-help, psychological interventions for the general population demonstrated that adding therapist guidance can improve treatment adherence and satisfaction, regardless of therapist expertise and qualifications (Shim et al., Reference Shim, Mahaffey, Bleidistel and Gonzalez2017), and that positive therapeutic relationships in an online environment may have a significant impact on treatment outcomes (Sucala et al., Reference Sucala, Schnur, Constantino, Miller, Brackman and Montgomery2012). There is also a randomised controlled trial that directly compared the effectiveness of online cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), either with or without telephone support, to online psychoeducation in dementia family carers (Fossey et al., Reference Fossey, Charlesworth, Fowler, Frangou, Pimm, Dent, Ryder, Robinson, Kahn, Aarsland, Pickett and Ballard2021). This study demonstrated that online CBT without telephone support led to significantly less improvement in mental health outcomes than online CBT with telephone support or psychoeducation. Consequently, the authors concluded that online CBT without telephone support should not be recommended for this population.

In the previous feasibility study of iACT4CARERS, therapist guidance was limited to written text feedback (Kishita, Gould et al., Reference Kishita, Gould, Farquhar, Contreras, Van Hout, Losada, Cabrera, Hornberger, Richmond and McCracken2022). Although this approach demonstrated acceptable levels of feasibility and acceptability in a sample of predominantly White family carers, an in-depth analysis of both the views of family carers and therapists highlighted the challenges of building effective therapeutic relationships through written feedback alone. Recommendations, therefore, suggested inclusion of some face-to-face online interactions (e.g. video call) between the family carer and their therapist (Contreras et al., Reference Contreras, Van Hout, Farquhar, Gould, McCracken, Hornberger, Richmond and Kishita2021; Reference Contreras, Van Hout, Farquhar, McCracken, Gould, Hornberger, Richmond and Kishita2022).

Pre-study consultations with this study’s Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) panel of dementia family carers from South Asian communities also highlighted the need for additional therapist guidance when using iACT4CARERS with family carers from ethnic minority groups. The PPI panel expressed that mental health problems are not always openly discussed in some communities and that some carers may feel less confident in the use of technology. Thus, the inclusion of additional one-to-one support sessions with the therapist alongside the online programme was recommended to improve the experiences of iACT4CARERS for family carers from ethnic minority groups.

Additional one-to-one sessions with therapists via telephone or video call were therefore embedded in the original version of iACT4CARERS used in the previous feasibility and acceptability studies; this updated version of iACT4CARERS (i.e. Enhanced iACT4CARERS) was used in the current study. Views on additional therapist guidance (i.e. one-to-one sessions) and experiences of Enhanced iACT4CARERS among family carers of people living with dementia from ethnic minority groups and their therapists were explored using a qualitative approach.

Method

Context

A qualitative research design, using framework analysis, was employed to explore the views on Enhanced iACT4CARERS among family carers of people living with dementia from ethnic minority groups and their therapists, with a particular focus on additional therapist guidance. This study is reported in line with the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) guidelines (O’Brien et al., Reference O’Brien, Harris, Beckman, Reed and Cook2014) (see Appendix 1 in the Supplementary material).

Sampling strategy

Recruitment took place between October 2022 and January 2023. In total, 14 participants (nine family carers and five therapists) agreed to take part in individual interviews to share their views and experiences of Enhanced iACT4CARERS. This sample size was informed by the concept of information power (Malterud et al., Reference Malterud, Siersma and Guassora2015).

Family carers

Dementia family carers who self-identified as being from an ethnic minority group were recruited through the Centre for Ethnic Health Research and Join Dementia Research (a national online recruitment tool). Members of the Centre for Ethnic Health Research who potentially met the study criteria were informed about the study by a Centre staff member. If they were interested in participating, a member of the study team contacted them to provide and discuss further details of the study. Family carers who were registered with Join Dementia Research were contacted directly by the study team to seek their interest in taking part in the study. We aimed to recruit at least five family carers from the Asian ethnic group as the UK primary care record on dementia diagnosis suggests that the Asian dementia patient group is the second largest group, following the White British patient group (Pham et al., Reference Pham, Petersen, Walters, Raine, Manthorpe, Mukadam and Cooper2018).

Family carers were eligible for participation if they were: (a) aged 18 and over, (b) an unpaid carer for a relative with a clinical diagnosis of dementia, (c) self-identifying as being from a minority ethnic group (Asian, Black, or any other or mixed minority ethnic backgrounds) and (d) willing to try/complete Enhanced iACT4CARERS before attending the interview. Thirteen family carers initially signed up for the study and agreed to complete Enhanced iACT4CARERS. All carers provided written consent via post or electronically. Two family carers did not start Enhanced iACT4CARERS after providing written consent. Further, two family carers completed two and five online sessions, respectively, without attending one-to-one sessions but declined to take part in the interview session. No reason for withdrawal was given by these four carers. The remaining nine family carers agreed to take part in the interview session to share their views and experiences of Enhanced iACT4CARERS. Family carers were encouraged to complete all eight online sessions and attend two one-to-one sessions with their therapist via telephone or video call. Family carers were invited to the interview regardless of whether they completed the whole programme or not.

Therapists

This study recruited five novice therapists from NHS mental health services. Therapists did not hold any formal qualification in clinical psychology, cognitive behaviour therapy, or counselling (e.g. assistant psychologist). Therapists attended a 2-day training on ACT and online feedback provision for this study. They were also trained to use the manual for one-to-one sessions, detailing the structure of sessions and providing the topic guide with example scripts. The detailed therapist manual, which includes access to all audio and video materials embedded in Enhanced iACT4CARERS, is currently only available to therapists who have completed the iACT4CARERS therapist training (if iACT4CARERS is found to be clinically effective in the ongoing full-scale trial, the manual and associated materials will be made available to practitioners). Drop-in group supervision sessions led by the lead researcher were also available every two weeks for the duration of the study. During the study, two or three family carers were randomly allocated to each therapist. Therapists were eligible to take part in the interview regardless of whether their allocated family carers completed the whole programme or not. All therapists consented to take part in the individual interview to share their views and experiences of working with ethnic minority family carers through Enhanced iACT4CARERS.

Intervention (Enhanced iACT4CARERS)

Enhanced iACT4CARERS consisted of the online programme iACT4CARERS, as tested in the previous feasibility and acceptability studies (Contreras et al., Reference Contreras, Van Hout, Farquhar, Gould, McCracken, Hornberger, Richmond and Kishita2021, Reference Contreras, Van Hout, Farquhar, McCracken, Gould, Hornberger, Richmond and Kishita2022; Kishita, Gould et al., Reference Kishita, Gould, Farquhar, Contreras, Van Hout, Losada, Cabrera, Hornberger, Richmond and McCracken2022), and two one-to-one sessions via telephone or video call with the therapist, each lasting 30 minutes. The online programme consisted of eight sessions: Table 1 describes each session. Sessions were made available to family carers five days after the completion of the previous session. Each session took about 30–50 minutes to complete each week depending on the number of self-learning activities included in each session as the number of these exercises differed from session to session. Family carers were informed that access to the online programme would cease after 12 weeks.

Table 1. Content of each session of iACT4CARERS

ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy.

In each online session, family carers were asked to engage in self-learning activities, such as watching videos and listening to audio exercises that illustrated ACT skills. These videos and audio materials were based on ACT exercises and metaphors adapted for dementia family carers (Kishita, Gould et al., Reference Kishita, Gould, Farquhar, Contreras, Van Hout, Losada, Cabrera, Hornberger, Richmond and McCracken2022). At the end of each session, the carers were encouraged to reflect on what was helpful in the session, identify a small step they could take that reflected their values and leave questions for their therapist if anything was unclear. This reflective element was mandatory to complete the sessions. Therapists provided individually tailored feedback to normalise difficult thoughts and emotions that family carers were experiencing, and to encourage them to practise ACT skills they found helpful after each session was completed.

A revision to the previous version of iACT4CARERS used in our feasibility and acceptability studies was the addition of two one-to-one sessions via telephone or video call with the therapist. Thus, the intervention is called Enhanced iACT4CARERS in this study. Family carers were given the option to book two 30-minute one-to-one sessions with their therapist while completing the online programme. Family carers were able to book these sessions anytime during the 12-week intervention phase. These sessions focused on encouraging the carers to: (a) express their feelings and emotional needs; (b) share their challenges and concerns regarding the use of a technology-based intervention; and (c) discuss their expectations for weekly reflection and online feedback from their therapist so that support could be tailored. These one-to-one sessions were optional and not signing up for these did not result in withdrawal from the intervention.

A manual containing detailed scripts for one-to-one sessions was developed by the Manual Development Working Group consisting of the lead researcher (clinical psychologist), two clinicians (clinical psychologist and occupational therapist) who work in NHS mental health services for older people, three therapists who took part in our previous feasibility and acceptability studies and two ethnic minority members from the public who have lived experience of caring for a family member living with dementia.

Data collection methods

Following consent, family carers were asked to complete a demographic questionnaire and standardised questionnaires assessing anxiety and depressive symptoms, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001), to characterise the sample. Following the 12-week intervention phase, family carers were invited to a semi-structured individual interview via video call. At the beginning of the interview session, family carers were asked to complete the Satisfaction With Therapy and Therapist Scale-Revised (Oei and Green, Reference Oei and Green2008), a 12-item self-report questionnaire assessing satisfaction with therapy and satisfaction with the therapist. An invitation to an individual interview via video call was also sent to five therapists at the end of the study.

The semi-structured interviews with both family carers and therapists lasted less than an hour. The purpose of conducting the interview was clearly explained to both family carers and therapists. All interviews were conducted by the same investigator (a female psychologist from an ethnic minority group) to ensure the consistency and reliability of the data collected. The same investigator led the study and therefore the interviewer had a relationship established with family carers and therapists prior to the commencement of follow-up interviews. To ensure consistency, an interview guide with open-ended questions and prompts to help explore family carers’ and therapists’ views of the intervention, with a particular focus on one-to-one sessions, was used (see Appendix 2 in the Supplementary material). Questions in the guide explored carers’ perceptions of the content of online sessions and one-to-one sessions, as well as their benefits and how they found the relationship with their therapist. The guide also explored therapists’ experiences of delivering the intervention, including the provision of written feedback and one-to-one sessions, as well as how they found therapeutic relationships with their carers. Digital audio recordings were transcribed verbatim. All transcripts were anonymised and checked for accuracy. Any personal identifiable information was removed.

Data analysis

Questionnaire data were analysed descriptively and used to characterise the sample. Interview data were analysed using a framework approach, employing inductive and deductive hybrid thematic analysis. This is a commonly used approach in healthcare research, particularly when exploring qualitative views in pilot and feasibility studies (Gale et al., Reference Gale, Heath, Cameron, Rashid and Redwood2013; O’Cathain et al., Reference O’Cathain, Hoddinott, Lewin, Thomas, Young, Adamson, Jansen, Mills, Moore and Donovan2015). The analysis of the qualitative data was led by M.R. (MSc in Rehabilitation Psychology) and E.V.H. (nurse, MSc in Human Sexuality Studies), with co-analysis by N.K. (psychologist, PhD in psychology). First, an initial systematic reading and re-reading of transcripts by two researchers (E.V.H. and N.K.) was carried out to enable familiarisation and in-depth understanding of the data. The initial coding framework was developed using pre-ordinate themes (relevance of the content, sense of connectedness, perceived benefits and areas for improvement) from the previous iACT4CARERS qualitative studies (Contreras et al., Reference Contreras, Van Hout, Farquhar, Gould, McCracken, Hornberger, Richmond and Kishita2021, Reference Contreras, Van Hout, Farquhar, McCracken, Gould, Hornberger, Richmond and Kishita2022) and emerging themes identified at the familiarisation stage. Following this stage, interviews were coded by M.R. and E.V.H., by applying the initial framework to the data using numerical codes. Discussions about the coding process took place between M.R. and E.V.H. The initial framework was updated with any discrepancies identified through those discussions. After coding all interviews (facilitated by NVivo 12), the framework was refined through a particular focus on the research questions and participants’ commonly expressed views and experiences by M.R., E.V.H. and N.K. Coded data were then charted into a framework matrix to summarise the data by themes. The characteristics identified in the charts were analysed for interpretation and the final analysis was reviewed by M.R., E.V.H. and N.K. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

To minimise researcher bias, the refined themes and sub-themes were presented to two family carers from ethnic minority groups with lived experiences of caring for a family member living with dementia, a professional from the Centre for Ethnic Health Research experienced in working with ethnic minority groups, and three therapists who took part in this study. This consultation process was utilised to assess whether their experiences were adequately represented and to incorporate their views into the analysis. The final consensus between M.R., E.V.H. and N.K. established the definitions and visual mapping of over-arching themes and sub-themes.

Results

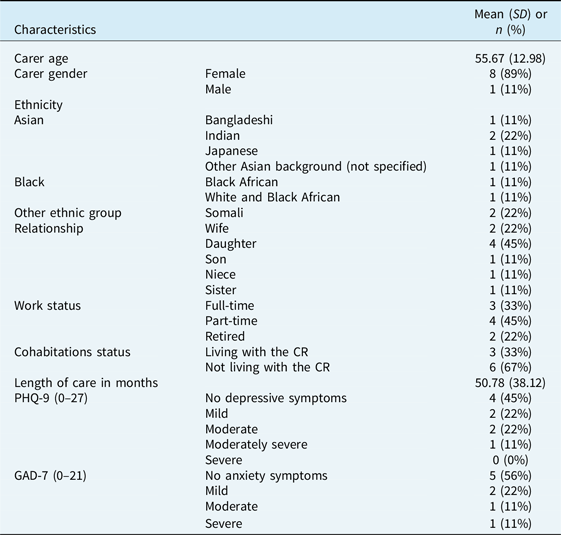

The characteristics of nine family carers who were interviewed are provided in Table 2. The majority were female, non-spousal family carers in either full-time or part-time employment. More than half of family carers were from an Asian ethnic group. The mean age of care recipients was 76.11 (SD=6.53), with the majority being female (n=6) and living with Alzheimer’s disease (n=5).

Table 2. Characteristics of carers who took part in the interview (n=9)

CR, care recipient; GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire.

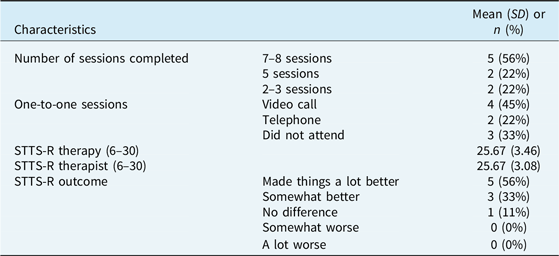

More than half of the family carers completed seven or all eight online sessions and the majority attended at least one optional one-to-one session (Table 3). Satisfaction with therapy and therapist were rated as high across family carers, with a mean of 25.67 (SD 3.46 and 3.08) for both subscales of the STTS-R. The majority reported that therapy made things somewhat or a lot better on the perceived outcome subscale of the STTS-R. Therapists (mean age 29.40, SD 3.14) who worked with these family carers were mainly female (n=4) and had a psychology background (clinical associate psychologist, n=1; trainee clinical associate psychologist, n=2; assistant psychologist, n=1; trainee doctor, n=1). Two of them had some experience in using ACT in their clinical work; the remaining three therapists did not.

Table 3. Treatment engagement data and satisfaction with therapy and therapist (n=9)

STTS-R, Satisfaction with Therapy and Therapist Scale-Revised. This is a 12-item self-report measure consisting of two subscales (satisfaction with therapy and satisfaction with therapist), with each item being rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Scores ranged from 6 to 30 per subscale, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction with therapy or the therapist. STTS-R outcome is a single item measuring perceived global improvement.

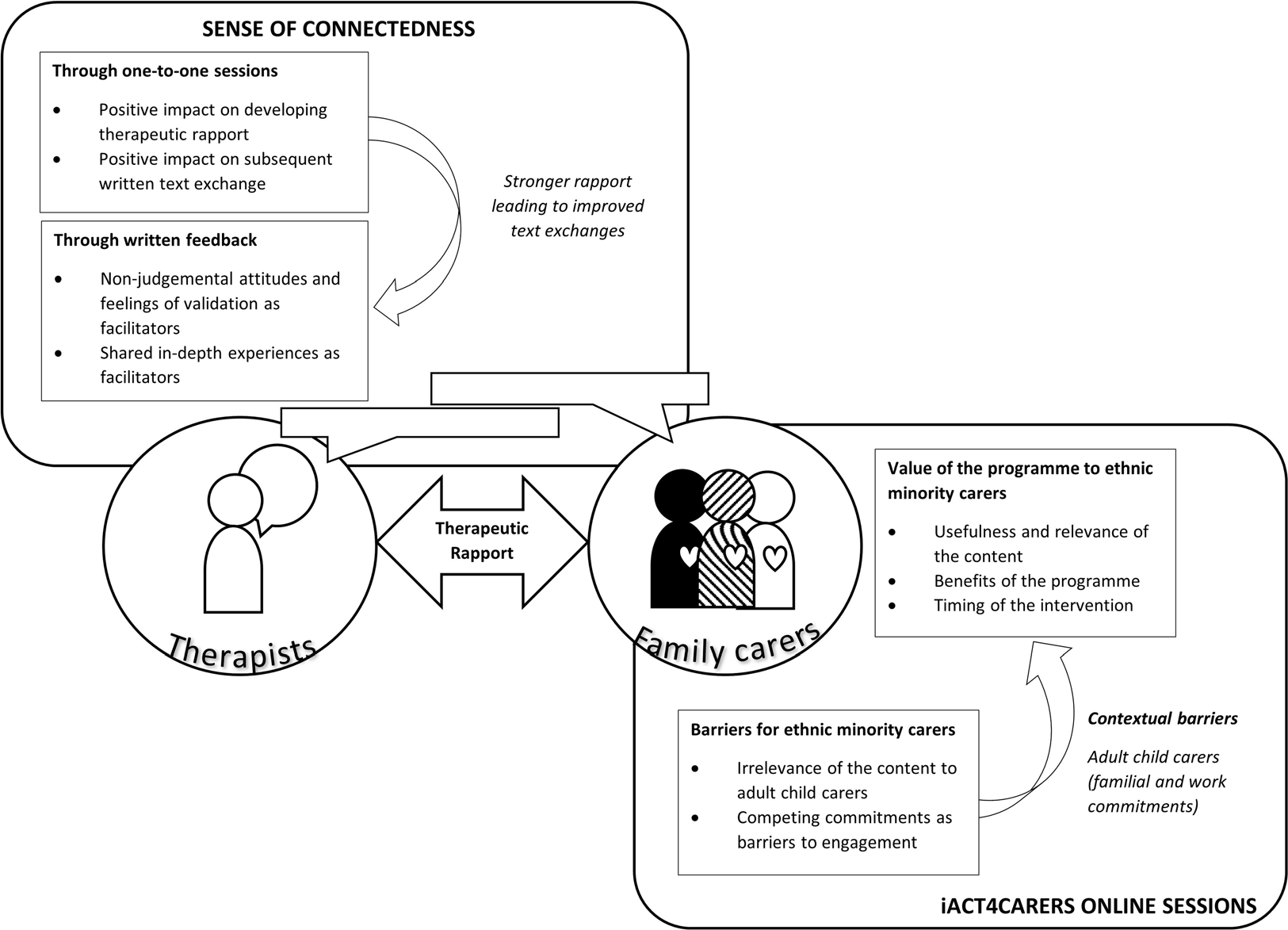

Four over-arching themes were identified relating to the family carers’ and therapists’ views of Enhanced iACT4CARERS: (1) Value of the programme to ethnic minority carers, (2) Barriers for ethnic minority carers, (3) Sense of connectedness through written feedback, and (4) Sense of connectedness through one-to-one sessions. An overview of the over-arching themes and sub-themes is provided in Fig. 1 and a narrative with supporting illustrative quotes are provided below.

Figure 1. Overview of over-arching themes and sub-themes.

Value of the programme to ethnic minority carers

Three sub-themes were identified with respect to the perceived value of the programme: ‘Usefulness and relevance of the content’, ‘Benefits of the programme’ and ‘Timing of the intervention’.

Usefulness and relevance of the content

Many carers commented on the value of being introduced to a range of ACT techniques throughout the online sessions and appreciated having the opportunity to discover techniques that worked best for them. Carers identified specific ACT metaphors which they found useful, such as the beach ball metaphor (which helps carers let go of the urge to control unwanted thoughts and feelings), and the garden of life metaphor (which encourages carers to reflect on their values and consider small steps they could take to bring about change in their lives). They reported that the online programme itself was very user-friendly and easily accessible, and video materials illustrating these ACT metaphors were very simple yet informative, and still effective despite their simplicity.

‘I thought it was very well put together and it was very educational, I found it very helpful, it explained a lot and I loved – I really, really enjoyed the videos, the cartoon and how it went through, without taking too much of time, what you’re going to be learning, what the learning outcome was and also understanding the particular about your feelings and understanding about particular feelings and emotions. It was just very educational, eye opening.’ (Carer 11, Somali)

‘I got the sense they really responded quite well to ACT. (…) Certainly [carer], I felt I got the sense [carer] was learning quite a lot about ACT as the weeks progressed and were trying to apply it to their situation which was great.’ (Therapist 1)

In addition to video materials, multiple carers mentioned how helpful audio-recorded materials were, such as the grounding exercises introduced at the beginning of each session, including an audio-guided self-compassion exercise. Carers found these useful in reframing their thinking, understanding and processing their emotions, and enabling self-forgiveness.

‘For me it was the one about, OK, you take yourself out of yourself and you look at yourself, and how would you think about what you’re observing. For me, personally, it was about that forgiveness, the self-forgiveness, and that really helped. And then it’s that, OK, in 10 years’ time what would you say about this situation. And actually it’s quite a positive thing, I would say, in 10 years’ time compared to how I was feeling at that point in time. So that technique really did help.’ (Carer 2, Asian)

Benefits of the programme

Many carers commented on how the programme met their needs and reported perceived benefits, such as reduced anxiety and increased ability to cope with their unwanted thoughts and feelings. They particularly highlighted that the programme helped them to learn how to live with anxieties or the experiences they struggle with rather than trying to control them. They also reported that completion of the programme reduced feelings of self-blame and perceptions of failure, for not being able to do everything for the person living with dementia.

‘How I was to how I am now, I feel more in control of my thoughts, I’m able to manage them better. I do accept some of the feelings I have are normal, if you like, if that’s the right word to use. You know, things like feeling guilty and such like. And it’s part of the journey, but it’s how to deal with it and look after myself, as well, which I am doing a lot more.’ (Carer 8, Black or Black mixed)

‘For [carer], she found it so valuable, (during one-to-one session) she said it would be something that she really wished everyone that she knew could – there could be something like that and it could be obviously rolled out more widely.’ (Therapist 2)

Timing of the intervention

While carers commended the programme for its value to them, regardless of the care recipients’ stage of dementia, some expressed the importance of considering the optimum time for introducing the programme. Some felt it would have been helpful to have access earlier in the caregiving journey, especially when the diagnosis was initially received.

‘I really wish I had access to this earlier because it really, really helped me reframe my thoughts. (…) when I was put into the situation of having to care for someone with advanced dementia at a time when I was grieving, and there was a lot of job insecurity, and lots and lots of pressures on me, I actually reached out to my doctor and social services to ask: “is there any help I can get?”. And I wasn’t receiving anything, and I struggled. I struggled a lot.’ (Carer 2, Asian)

Barriers for ethnic minority carers

Two sub-themes were identified as potential barriers: ‘Irrelevance of the content to adult child carers’ and ‘Competing commitments as barriers to engagement’.

Irrelevance of the content to adult child carers

Unlike the previous feasibility study of iACT4CARERS, where study participants were mainly spousal, retired, White British carers, the majority of family carers in this study were adult child carers. They either had a full-time or part-time job and other familial commitments, such as childcare. Family carers explained that the main care responsibilities tend to fall on adult children within their communities and care is often shared between several of them. These cultural differences, in terms of expectations within the family, affected how family carers perceived the content of the online sessions. That is, carers expressed how the current examples of carer experiences presented in the programme did not reflect their lived experiences. During one-to-one sessions, therapists also noted that carers expressed frustration about the irrelevance of the content due to such differences.

‘(…) in ethnic minority communities there tends to be a big family support mechanism, large family circle, so people will be coming and giving. (…) and maybe it’s something around a challenge that an ethnic minority would face, rather than it’s seeing friends and seeing people, it’s because some families, there’s multiple people in the family in the house, so it’s not a case of isolation, it’s more case of being comfortable being vulnerable and saying, “I’m not coping. (…) and the challenge I may be facing is you have a perception that I should be strong, that it’s my duty to do this as the spouse or the child or the parent” (…) so maybe the example – a little bit more realistic to an ethnic minority participant – may provide even better outcomes.’ (Carer 2, Asian)

‘[Carer] mentioned that sometimes they found it frustrating that a lot of the examples were based upon carers who weren’t working fulltime as well, and although they understood why that was, they sometimes, at times, found that a little bit frustrating.’ (Therapist 4)

Competing commitments as barriers to engagement

Distractions, priorities, and other commitments were frequently mentioned as barriers affecting carers’ ability to engage in the programme. Factors such as work and childcare competed for their time and attention, making it difficult for them to sit down and concentrate on the content. These competing demands also made it more challenging for carers to book one-to-one sessions with their therapist as these sessions were offered during normal working hours.

‘It was my own discipline, finding time for me to say on that particular day, I’m going to sit down, I’m going to do this because of my life. My work is just so hectic and I’m a mother of four children. (…) so it was a lot.’ (Carer 11, Somali)

‘Because I was working Monday to Friday, and it wasn’t like a weekend thing at first. (…) on the weekend, I was a bit busy as well because I’ve got my kids that go to school Monday to Friday and the weekends, they really wanted some time. (…) I don’t think I could have booked it (one-to-one session) after like – I didn’t want to book it after like four, five o’clock in the evening.’ (Carer 7, Asian)

‘It seemed to be what was going on in their lives seemed to have influenced how well they wanted to engage with the process.’ (Therapist 4)

Sense of connectedness through written feedback

Two sub-themes were identified with respect to written feedback: ‘Non-judgemental attitudes and feelings of validation as facilitators’ and ‘Shared in-depth experiences as facilitators’.

Non-judgemental attitudes and feelings of validation as facilitators

Written feedback exchanged between therapists and carers following each session seemed to be an important factor for both parties, enabling them to build relationships with each other. Many carers expressed positive views and appreciation towards the feedback they received from therapists who were always perceived as being non-judgemental, noting that it encouraged them to continue with the programme, provided support and validation, and helped them consider different ways of overcoming their struggles and achieving their goals.

‘I guess it’s more validation, so it was non-judgmental. (…) I felt that it was understood, what I was saying was understood. And yes, it was quite encouraging, encouraging to carry on, as validated that I understood that module.’ (Carer 2, Asian)

‘(Looking at feedback comments the therapist had provided, which the therapist had kept in their own reflective notes) the feedback I’ve put on my reflections is a lot about encouragement, which is in keeping with the approach of ACT.’ (Therapist 5)

Shared in-depth experiences as facilitators

Written comments submitted by carers also had a significant impact on therapists’ views about the development of therapeutic rapport. Therapists were able to foster a strong sense of therapeutic rapport even through written text exchanges, particularly when carers left comments consistently across sessions and wrote longer comments sharing their in-depth experiences.

‘The comments were a bit longer that they left so I thought I could engage more back and talk through and also because it was all of the sessions that they were involved in, we built up a bit of a therapeutic rapport through that.’ (Therapist 2)

Conversely, therapists reported how the lack of in-depth comments limited their ability to develop rapport.

‘The relationship never really kind of started at all, because I guess there were very few pleasantries exchanged, or very few details exchanged in the actual feedback that they were giving.’ (Therapist 4)

Sense of connectedness through one-to-one sessions

Two sub-themes were identified in relation to one-to-one sessions: ‘Positive impact on developing therapeutic rapport’ and ‘Positive impact on subsequent written text exchange’.

Positive impact on developing therapeutic rapport

Both carers and therapists highlighted the helpfulness of one-to-one sessions in building therapeutic rapport and relationships, particularly when sessions were delivered via video call rather than telephone. Many carers and therapists mentioned the satisfaction of seeing the person they had been exchanging feedback with, emphasising that the visual element made the interaction feel more genuine and personal.

‘(During one-to-one sessions) I felt [therapist] was compassionate, she was friendly, she listened to what I was saying and took on board my problems, concerns, issues and I felt that I did build up a rapport with her, yes. Even though I wasn’t seeing her for the therapy. (…) I felt that I could be open with her and honest and I trusted her and likewise I felt she was very supportive and she really did seem to know where I needed that help.’ (Carer 8, Black or Black mixed)

‘I thought one-to-one sessions were excellent. Actually, after having the session, it gave a chance for carers to get to know you, and see you face-to-face, I think adds a bit of reality to the situation, but otherwise it sometimes feels like you’re almost talking to a machine.’ (Therapist 4)

There was a clear preference for video calls over telephone calls, with some therapists finding one-to-one sessions via telephone more challenging, particularly in terms of achieving clear communication and understanding accents. Therapists valued sensory information such as body language and facial expressions obtained during one-to-one sessions, which enhanced a sense of connectedness.

‘It just feels more personable and there’s a bit more of a connection, the more, I guess, that increases from online to telephone, and then I think it would again increase from telephone to at least virtual, if not face-to-face. So, I think the more sensory information you have about a person, the more connected you feel.’ (Therapist 5)

There was a clear lack of connection evident when one-to-one sessions did not take place. Both carers and therapists felt that the exchange of written text alone did not allow a relationship to develop.

‘I didn’t do any one-to-one sessions, so the relationship was just through me doing my session and them giving me the feedback. So, I wouldn’t really say I had a relationship with them. To be honest I didn’t feel any connection.’ (Carer 7, Asian)

‘I guess another challenge was that I didn’t know [carer] well, so it was – I guess there was no therapeutic rapport beyond the (written) feedback. So I don’t know if that would’ve helped, if [carer] would’ve felt more able to talk or more comfortable to talk if we’d have known each other better.’ (Therapist 5)

Positive impact on subsequent written text exchange

Both carers and therapists found that their interaction through one-to-one sessions improved the quality of subsequent written text exchanges. One-to-one sessions enhanced therapists’ ability to understand carers’ current situation and thus their comments, and it allowed them to tailor their feedback specifically to each carer.

‘One-to-one sessions really helped me visualise the person that we were trying to support. They shared a lot of their background that they didn’t share obviously in their feedback and helped me guide the feedback a little bit more specifically to them. It allowed the feedback, I think, to be a little bit more focused.’ (Therapist 4)

Carers found putting a face to their therapist’s name by attending one-to-one sessions helpful. As a result, they reported becoming more open and personal in their comments following one-to-one sessions, which was noted by their therapists.

‘(…) it was good to meet my therapist and have that I could visually… you know, when I’m writing to her it was great to put a face to her name.’ (Carer 8, Black or Black mixed)

‘After the first one to one session, actually I thought the feedback was more flowing, and I thought the carer became more open, and more willing to share their experiences as well, which I think after that, it means that I could actually give better feedback and better support as well.’ (Therapist 4)

Discussion

This study explored the views of family carers of people living with dementia from ethnic minority groups and their therapists on Enhanced iACT4CARERS. In line with the previous feasibility and acceptability studies of iACT4CARERS, family carers from ethnic minority groups valued ACT techniques, highlighting their accessibility, usefulness and simplicity, which led to perceived benefits. The key element of the intervention that led to such benefits was self-forgiveness, which helped carers to step back from self-critical thoughts and embrace feelings of guilt and failure. Although research on compassion-focused interventions for family carers is still limited, emerging evidence suggests that these types of interventions have some potential utility in supporting family carers (Murfield et al., Reference Murfield, Moyle and O’Donovan2021). The appreciation for this key element is also consistent with the previous study of iACT4CARERS, conducted mainly with White British carers, where an audio-guided self-compassion exercise (learning to be kind, supportive and encouraging to oneself) was the most valued exercise among the majority of carers (Contreras et al., Reference Contreras, Van Hout, Farquhar, McCracken, Gould, Hornberger, Richmond and Kishita2022).

Carers’ engagement with the programme in the current study was facilitated by feelings of validation and encouragement received from their therapist via written feedback each week. This is consistent with the previous study of iACT4CARERS (Contreras et al., Reference Contreras, Van Hout, Farquhar, McCracken, Gould, Hornberger, Richmond and Kishita2022). This is also similar to the findings from a systematic review of internet-delivered, self-help, psychological interventions, which demonstrated that scheduled consistent support from therapists was an important factor in predicting adherence to, and efficacy of, such interventions (Shim et al., Reference Shim, Mahaffey, Bleidistel and Gonzalez2017).

There were some differences from the findings of the previous feasibility study of iACT4CARERS. Some of the ethnic minority family carers described some of the online content in the current study as irrelevant. This was not related to the cultural relevance of the ACT metaphors or the exercises themselves. ACT is being implemented and researched across numerous countries around the world, and thus its metaphors and exercises have been validated with a presumably diverse population (Woidneck et al., Reference Woidneck, Pratt, Gundy, Nelson and Twohig2012). The reported irrelevance was related to the use of examples of carer experiences that did not reflect ethnic minority carers’ cultural context. In terms of their relation to the cared-for person, carer participants in this study differed slightly from those who took part in the previous study (i.e. adult child carers versus spouses). In some ethnic minority groups, such as South Asian communities, caring for older family members is seen as an ingrained, culturally expected (sometimes religious) responsibility (Andruske and O’Connor, Reference Andruske and O’Connor2020). Therefore, the main care responsibilities within these communities tend to fall on adult children. Family carers in this study were mainly adult children juggling multiple competing demands, such as work and childcare. Some felt that the challenges they faced were not reflected in the examples used. For example, some carers mentioned that while it is not challenging to find an alternative carer within their family, as families tend to be large in their community, it can be difficult to express that they are struggling and need a break from caregiving due to the sense of guilt for not fulfilling their familial obligation. It was suggested that these types of culturally informed attitudes could be more directly addressed in the programme. In fact, dementia carer research shows that such cultural values (familism) can affect mental health problems differently in family carers across different cultures (Falzarano et al., Reference Falzarano, Moxley, Pillemer and Czaja2022; Losada et al., Reference Losada, Shurgot, Knight, Márquez, Montorio, Izal and Ruiz2006). This suggests the need for cultural adaptation of psychological interventions for ethnic minority carers in future research.

Results in the current study are consistent with the findings of a recent systematic review on cultural adaptation of internet- and mobile-delivered interventions for mental disorders (Spanhel et al., Reference Spanhel, Balci, Feldhahn, Bengel, Baumeister and Sander2021). This systematic review explored the impact of surface adaptation (e.g. the adaptation of case examples used) and deep adaptation (e.g. addressing mental health literacy) and demonstrated that such adaptations are important and the effectiveness of culturally adapted online interventions is comparable to the respective original interventions. However, this systematic review showed no link between the extent of the conducted cultural adaptations (surface versus deep) and the effectiveness of such interventions. Consequently, the current literature cannot answer how much cultural adaptation is enough to bring about change in general. Future research needs to explore the effectiveness of different levels of cultural adaptation on clinical outcomes among family carers from ethnic minority groups.

It is important to emphasise that ethnic minority groups are heterogeneous, representing a broad range of protected characteristics, and can have diverse needs that may be influenced by differing sociocultural contexts. The carer sample in the current study was certainly heterogeneous and this could limit the generalisation of the findings of this study to a broader population. Future research needs to explore whether it is essential to develop tailored internet-delivered ACT for family carers from different ethnocultural groups.

A recent study, which explored the need for cultural adaptation of CBT (STrAtegies for RelaTive programme) for Black and South Asian family carers of people living with dementia, demonstrated that different tailored treatment manuals are not necessary for each of the groups (Webster et al., Reference Webster, Amador, Rapaport, Mukadam, Sommerlad, James, Javed, Roche, Lord, Bharadia, Rahman-Amin, Lang and Livingston2023). The study showed that changes such as making names culturally neutral, and pictures ethnically diverse, and emphasising confidentiality, are relevant to all populations and could benefit people from different backgrounds.

Furthermore, ACT is a transdiagnostic contextual behaviour therapy, which aims to facilitate psychological flexibility through three sets of skills: stepping back from restricting thoughts and approaching or allowing painful emotions; focusing on the present, connecting with what is happening in the moment; and clarifying and acting on what is most important to do and building larger patterns of effective values-based action (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Levin, Plumb-Vilardaga, Villatte and Pistorello2013). These sets of skills are known to be transcultural processes underpinning mental health problems in dementia family carers across different cultures (Kishita, Morimoto et al., Reference Kishita, Morimoto, Márquez-González, Barrera-Caballero, Vara-García, Van Hout, Contreras and Losada-Baltar2022). Thus, ACT has a potential to be effective for wider groups of carers.

In the current study, 56% of carers completed seven or all eight online sessions, while this completion rate was 70% in the previous study of iACT4CARERS (Kishita, Gould et al., Reference Kishita, Gould, Farquhar, Contreras, Van Hout, Losada, Cabrera, Hornberger, Richmond and McCracken2022). Although these rates need to be compared with caution as the sample sizes are small and different across the two studies, and we did not screen family carers for anxiety or depressive symptoms in the current study, this is in line with previous studies reporting higher drop-out rates for internet-delivered self-help interventions among ethnic minority individuals (Ramos and Chavira, Reference Ramos and Chavira2022). The main reported reason for stopping the intervention in this study was a lack of time due to other commitments, such as childcare, rather than a lack of confidence in the use of technology, which is one of the key factors reported in previous studies (Ramos and Chavira, Reference Ramos and Chavira2022). In addition, family carers who were not presenting clinical levels of anxiety or depressive symptoms at screening were more likely to drop out in this study, which is understandable as their priority for the intervention may be reduced particularly when faced with such competing demands. This suggests that internet-delivered, self-help interventions for carers, such as Enhanced iACT4CARERS, may not be ideal to be used as a preventative approach targeting family carers from ethnic minority groups who are currently not presenting any mental health difficulties, and future research should carefully consider the target carer population.

The findings of the current study also demonstrated that, despite their brevity, additional one-to-one support sessions with the therapist allowed carers and therapists to develop strong therapeutic relationships. This enhanced subsequent written text exchanges, allowing carers to be more open and engaged. In turn, a strong sense of connectedness helped therapists tailor their feedback. The challenges of building good therapeutic relationships through written feedback alone were reported by both family carers and therapists in the previous study of iACT4CARERS (Contreras et al., Reference Contreras, Van Hout, Farquhar, Gould, McCracken, Hornberger, Richmond and Kishita2021, Reference Contreras, Van Hout, Farquhar, McCracken, Gould, Hornberger, Richmond and Kishita2022), but were not evident in the current study, which used Enhanced iACT4CARERS. This suggests that additional one-to-one support sessions may promote the engagement level of family carers. Considering that all family carers who presented clinical levels of anxiety or depressive symptoms at screening signed up for additional one-to-one support sessions, and presented better completion rates in the current study, Enhanced iACT4CARERS may be more beneficial for family carers of people living with dementia from ethnic minority groups with heightened psychological needs.

There were some limitations to the study. Family carers were recruited through the Centre for Ethnic Health Research and Join Dementia Research. As such, many had a good level of literacy regarding the purpose and process of research. The majority of them also had a high level of education as five of nine carers had completed a university degree, which may have contributed to the opinion, such as regarding simplicity of materials. We did not include any family carers who were not able to speak English and would have required an interpreter. The participation of non-Asian ethnic minority family carers, such as carers from Black communities, was also limited. A lack of understanding of the concept of research, the ability to speak English and other socio-cultural barriers which result in health inequalities are considered the critical factors contributing to the under-representation of ethnic minorities in health and social care research (Farooqi et al., Reference Farooqi, Jutlla, Raghavan, Wilson, Uddin, Akroyd, Patel, Campbell-Morris and Farooqi2022). The transferability of the findings of this study may be limited due to the convenience sampling.

The study did not collect data on the ethnicity of therapists and thus we do not know whether ethnic matching of patient and therapist had any impact on the findings. However, a previous meta-analysis on ethnic matching of patients and therapists in mental health services demonstrated that although people tend to prefer having a therapist of their own ethnicity and tend to perceive therapists of their own ethnicity somewhat more positively than others, treatment outcomes do not differ when patients do or do not have a therapist of their same ethnicity (Cabral and Smith, Reference Cabral and Smith2011).

In qualitative research it is important to create a context in which participants feel comfortable enough to share freely with researchers, and some research indicates that matching ethnicity between participant and investigator can have positive effects in qualitative research (Roche et al., Reference Roche, Higgs, Aworinde and Cooper2021). Therefore, a researcher from an ethnic minority group conducted all interviews. As this researcher had a relationship established with family carers before the commencement of follow-up interviews, this may have biased the findings. However, the data analysis was led by two independent researchers, and external public members and therapists were involved in confirmation of data interpretation. The interviewer did not attend any meetings with these individuals to avoid influencing data interpretation.

Finally, a recent systematic review on studies empirically assessing sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research demonstrated that qualitative studies using empirical data reached saturation between 9 and 17 interviews, with a mean of 12–13 interviews (Hennink and Kaiser, Reference Hennink and Kaiser2022). Although no new aspects, dimensions, or nuances of codes were identified in interviews that were conducted at a later stage, our sample size was particularly small for the therapist group. Thus, the findings will need to be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

Carer support is essential for maintaining psychological well-being. Family carers from ethnic minority groups may have a greater need for such support due to the lack of resources tailored to their needs. ACT has a potential to be acceptable to wider groups of carers due to its transdiagnostic and transcultural nature. However, regardless of the format of delivery, previous studies that utilised ACT for family carers of people living with dementia have not targeted carers from ethnic minority groups or reported the ethnicity of the study sample. This study recruited ethnic minority dementia carers and explored their views on internet-delivered self-help ACT tailored for dementia family carers. This study demonstrated that ACT metaphors and exercises may be acceptable to ethnic minority carers, although this can be hindered by using examples of carer experiences that do not reflect their cultural context. Additional one-to-one support sessions allowed the development of effective therapeutic relationships, improving experiences of both carers and therapists. This blended approach may be particularly beneficial for ethnic minority dementia carers presenting with psychological symptoms. Future research could explore the varying degrees and dose of contact with a therapist required to maximise the effectiveness of self-help carer interventions.

Key practice points

-

(1) Internet-delivered self-help acceptance and commitment therapy may be acceptable to family carers from ethnic minority groups.

-

(2) Regular online written feedback from therapists can help carers achieve their goals through increased feelings of validation and encouragement.

-

(3) Brief one-to-one sessions with the therapist alongside the online sessions can help develop effective therapeutic relationships. This can improve the quality of subsequent text-based online interactions between carers and therapists.

-

(4) Adapting examples of carer experiences embedded in interventions to accommodate cultural differences in family dynamics may lead to improved acceptability.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X24000102

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, N.K. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank our patient and public involvement research partners Ruby Ali-Strayton and Firoza Davies for their invaluable insights at every stage of the design and conduct of the research. The authors also would like to thank Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust, Hertfordshire Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust and Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust, as well as all the trial therapists from these Trusts for their enormous support. The huge contribution of principal investigators is duly acknowledged: Dr Anna Forrest and Dr Shaheen Shora. Thank you also to all the collaboration group members (in alphabetical order): Chris Pitt, Connie Clements, Gabriella Hyslop, Jack Avison, Jasmin Plant, Dr Michael Albert, Dr Milena Contreras and Shiona Whitmore.

Author contributions

Naoko Kishita: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Funding acquisition (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Resources (lead), Supervision (lead), Visualization (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Barbara Czyznikowska: Formal analysis (supporting), Funding acquisition (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Validation (supporting), Visualization (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Megan Riggey: Formal analysis (lead), Validation (lead), Visualization (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Elien Van Hout: Conceptualization (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Validation (supporting), Visualization (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Erica Richmond: Funding acquisition (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Rebecca Gould: Conceptualization (supporting), Funding acquisition (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Lance McCracken: Conceptualization (supporting), Funding acquisition (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Morag Farquhar: Conceptualization (supporting), Funding acquisition (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

This study is funded by the NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme (Award ID: NIHR150071). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

Full ethical approval was obtained from the NHS London-Queen Square Research Ethics Committee (22/PR/0743). The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. This study also has been performed in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave informed consent to participate in the study and for the results to be published.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.