The numbers of patients with dementia and/or delirium in general hospitals are significant, with about half of patients over the age of 65 having dementia, delirium or both conditions.Reference Boustani, Baker, Campbell, Munger, Hui and Catelluccio1–3 A number of studies have highlighted that people with dementia are more than twice as likely to be admitted to hospital when compared with people who do not have dementia.Reference Phelan, Borson, Grothaus, Balch and Larson4, Reference Tuppin, Kusnik-Joinville, Weill, Roicordeau and Allemand5 Research suggests that there is a need for education and training in this area to address a lack of knowledge and skills.Reference Dewing and Dijk6–Reference Moyle, Olorenshaw, Wallis and Borbasi8 The aim of this review was to evaluate the effectiveness of educational interventions aimed at staff to improve the care and management of older people with delirium and/or dementia in general hospitals. This was part of a wider review focusing on improving the care and management of older patients with cognitive impairment in general hospitals.

Method

The review design was informed by guidance for systematic reviews in healthcare9 and the PRISMA reporting guidelines.Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Group10 This included writing a review protocol, which outlined the review methods, starting with the formulation of a precise review question and ending with a proposed strategy for data synthesis. A mixed-methods design was planned to elicit evidence not only on the effectiveness of interventions but also on the various aspects of interventions that contribute to their effectiveness. A design combining qualitative and qualitative evidence was planned according to the Joanna Briggs Reviewers' Manual for Mixed Methods Reviews.11

A search strategy was developed to undertake an initial wider review into the care and management of older patients with cognitive impairment in general hospitals. See Appendix 1 for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Details of the databases used and the search strategy can be found in supplementary Appendix 1 and the PRISMA checklist in supplementary Appendix 2, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.29.

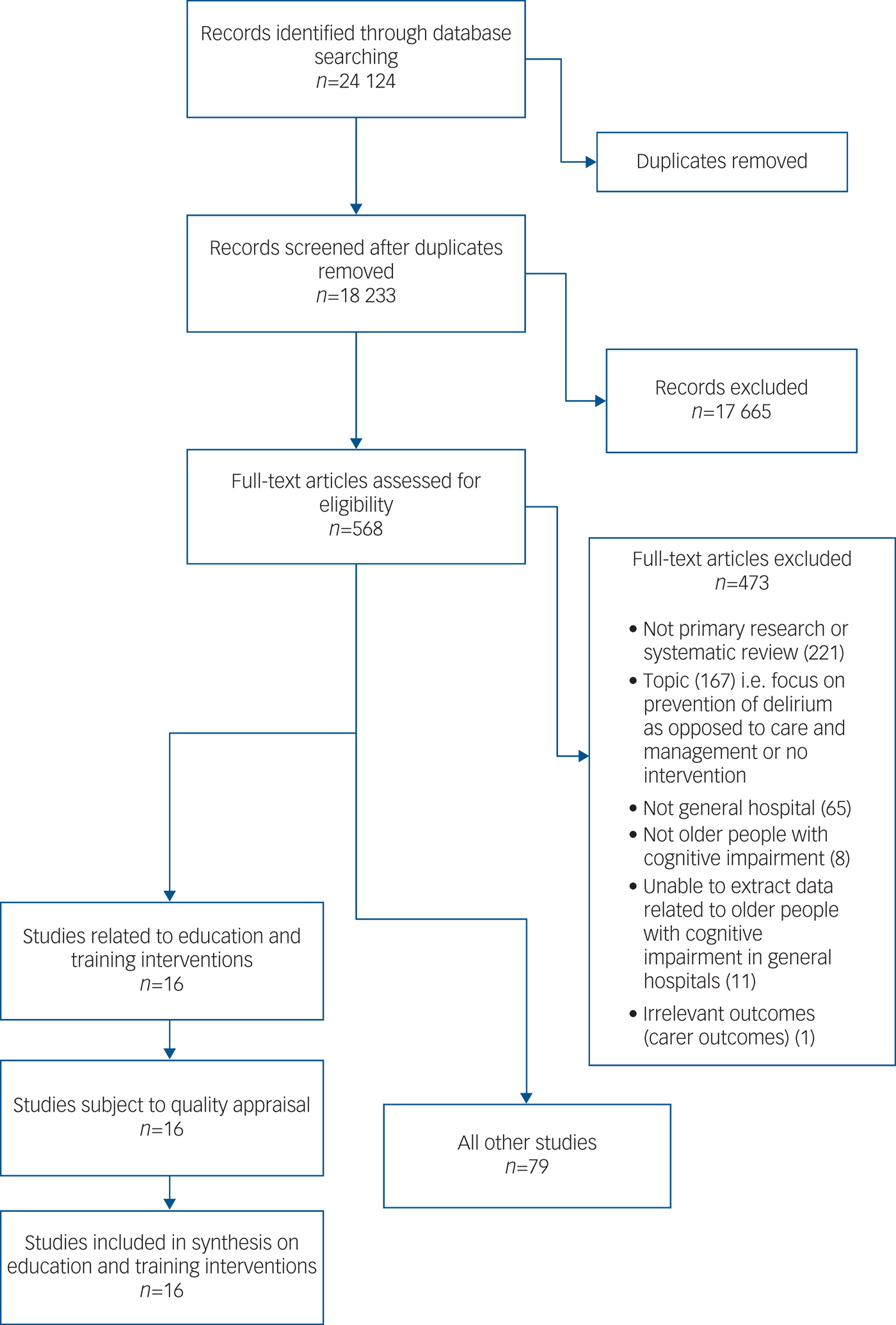

The combined initial and updated search on the care and management of older people with cognitive impairment in general hospitals returned 18 233 citations after de-duplication. For both the initial search and the updated search, titles and abstracts where available, were independently screened by at least two of the reviewers using EndNote (v7). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or for a small number of papers, by involving a third reviewer. Full text of all articles to be included were obtained for further scrutiny. Two reviewers independently screened the full text, again resolving any disagreements by discussion. Papers that met inclusion criteria were subject to quality appraisal and data extraction.

The quality of the studies was assessed in two parts: the risk of bias was assessed using criteria recommended by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Review GroupReference McAuley and Ramsay12 and the external validity was checked using a customised form based on the Guide for Useful Interventions for Physical Activity in Brazil and Latin America (GUIA) External Validity Assessment Tool.13 This form was selected and customised when no other suitable forms could be found. One researcher completed this process. The results were independently checked for accuracy and completeness. A customised data extraction form was used to extract the following information: author, year, study design, results and conclusion and the results were independently checked by another researcher.

As a result of the clinical and methodological diversity of papers identified, it was anticipated that a meta-analysis would not be possible and so a narrative synthesis, using an aggregative approach was adopted. One researcher led on data synthesis, with weekly meetings being held with the lead researcher to discuss each stage of the process (see below for an outline of the four-stage process adopted). The narrative synthesis was informed by the Economic and Social Research Council framework for conducting narrative synthesis in systematic reviews.Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai and Rodgers14 This comprises four distinct stages, although it is recognised that these stages will not be pursued sequentially but iteratively, with movement back and forth between the four stages.

The first stage, developing a theory as to how the interventions work, was done by constructing diagrams showing possible linkage between the various elements. The second stage: developing a preliminary synthesis, involves briefly describing each study and presenting this in a way that allows comparisons to be made across studies. This was done by recording details of the studies in an Excel spreadsheet. The next stage is to explore relationships within and between studies. This was particularly challenging because of the heterogeneity of the studies included. There was variability in study design, in the populations that were involved in the studies, in the educational interventions used (for example some focused on delirium and others on dementia, some involved face-to-face teaching and others used online training) and also in the settings in which they were used (i.e. some were wards, others were departments such as the emergency department). The final stage is assessing the robustness of the synthesis, including considering the methodological quality of the studies included and the trustworthiness of the final outcome of the synthesis. The former was done as part of the quality appraisal process and clearly has an impact on the latter.

All the studies included have at least one element of their design that was flawed. However, despite this, in the absence of other more methodologically robust studies, all were considered to be of some value and were therefore included, with the subsequent limitations of the review overall clearly acknowledged.

Results

A total of 16 articles related specifically to education and training on the care of older people with cognitive impairment in general hospitals and are reported on in this paper (see Fig. 1 Flow chart of included studies).Reference McCrow, Sullivan and Beattie15–Reference Teodorczuk, Mukaetova-Ladinska, Corbett and Welfare30 Out of the 16 papers included, eight were about delirium training, six focused on dementia care training and a further two on training to improve care of confused older patients generally (delirium and dementia). Summaries of the included studies can be found in Table 1. The majority of papers were before and after studies (n = 12). A further two were post-intervention questionnaire studies. One study was a cluster randomised controlled trial and another a stepped-wedge cluster randomised trial.

Fig. 1 Flow chart of included studies: the initial and updated searches combined.

Table 1 Summary of included studies: delirium training, dementia care training, dementia and delirium training

CPOE, computerised provider order entry; IV, intravenous; CAM, Confusion Assessment Method; AHP, Allied Health Professional ; F1, Foundation year 1; CODE, Confidence in Dementia scale; KIDE, Knowledge in dementia scale.

The eight studies related to delirium training were undertaken in a range of countries (Australia, Belgium, Canada, India, the Netherlands, USA). Two of these studies were cluster randomised controlled trials. One was a stepped-wedge cluster randomised trial, four were quasi-experimental studies with no control group and one was a small-scale pilot study. All studies measured the effect of an educational intervention on various outcomes including participants' knowledge of delirium/dementia. Of the six studies on dementia care training, three were from the USA, two from the UK and one from Australia. Five of the studies were quasi-experimental studies with no control group and one was a randomised controlled trial. Two studies on delirium and dementia training were both quasi-experimental, adopting a pre-test/post-test design.

Intervention characteristics

The education and training interventions used in the studies varied.

Delirium training

Four of the interventions were aimed at nurses. Of these, one evaluated an educational website,Reference McCrow, Sullivan and Beattie15 another a 50 min in-service lecture,Reference Meako, Thompson and Cochrane16 the third an e-learning course.Reference van de Steeg, Ijkema, Langelaan and Wagner17 The fourth did not specify details of the intervention.Reference Varghese, Macaden, Premkumar, Mathews and Kumar18 Interventions in two studies were aimed at doctors. The first evaluated a combination of a 2 min in-service training and the introduction of a bedside care checklist to screen for delirium.Reference Olveczky, Mattison and Mukamal19 The second evaluated a combination of seminars and grand rounds.Reference Rockwood, Cosway, Stolee, Kydd, Carver and Jarrett20 The remaining two studies comprised interventions that were aimed at multidisciplinary teams: e-learning modulesReference Detroyer, Dobbels, Debonnaire, Irving, Teodorczuk and Fick21 and a 30 min face-to-face session.Reference Toye, Kitchen, Hill, Edwards, Sin and Maher22

Dementia care training

Of the six studies, five used classroom teaching ranging from 2 to 10 h in lengthReference Elvish, Burrow, Cawley, Harney, Graham and Pilling23–Reference Ouldred and Roberts27 and one used a specially designed educational DVD.Reference Weitzel, Robinson, Mercer, Berry, Barnes and Plunkett28 The interventions varied in their target audiences. Four were for a variety of staff disciplines, two for nurses and one for physicians.

Delirium and dementia training

One intervention consisted of three online learning modules with access to an educational resource officer and was aimed specifically at nurses.Reference Horner, Watson, Hill and Etherton-Beer29 The other was aimed at all disciplines and involved attending two face-to-face study days.Reference Teodorczuk, Mukaetova-Ladinska, Corbett and Welfare30

Study quality

Delirium training

A summary of the quality of the eight studies can be found in Appendix 2. Only three of the studies used a control group.Reference McCrow, Sullivan and Beattie15, Reference van de Steeg, Ijkema, Langelaan and Wagner17, Reference Varghese, Macaden, Premkumar, Mathews and Kumar18 The lack of control group in the remaining five studies leads to a high risk of internal bias. One study used cluster randomisation to allocate one ward to the intervention group and one ward to the control group.Reference Varghese, Macaden, Premkumar, Mathews and Kumar18 However, there is a high risk of contamination bias as the intervention took place at a single hospital. Masking was absent in all but two studies,Reference van de Steeg, Ijkema, Langelaan and Wagner17, Reference Rockwood, Cosway, Stolee, Kydd, Carver and Jarrett20 meaning performance bias was likely in the other six studies.Reference McCrow, Sullivan and Beattie15, Reference Meako, Thompson and Cochrane16, Reference Varghese, Macaden, Premkumar, Mathews and Kumar18, Reference Olveczky, Mattison and Mukamal19, Reference Detroyer, Dobbels, Debonnaire, Irving, Teodorczuk and Fick21, Reference Toye, Kitchen, Hill, Edwards, Sin and Maher22 In addition, only one of the studies reported using a power calculation.Reference van de Steeg, Ijkema, Langelaan and Wagner17

Dementia care training

For the six studies focusing on dementia care training, only one used a control group.Reference Ouldred and Roberts27 Two were pilot studies and had a small number of participants.Reference Ouldred and Roberts27, Reference Weitzel, Robinson, Mercer, Berry, Barnes and Plunkett28 Only one study reported using a power calculation.Reference Elvish, Burrow, Cawley, Harney, Graham and Pilling23 See Appendix 2.

Dementia and delirium training

Neither of the two studies had a control group and thus the risk of internal bias was high. Neither used a power calculation. See Appendix 2.

Outcome measures

All of the delirium education and training studies used questionnaires as the main outcome measures, with each study using different questionnaires. The questionnaires varied in length from 2 to 34 questions and in quality (some had undergone psychometric analysis and validation and others had not). The outcome measures used for the dementia care education and training studies were more diverse. For the studies on delirium and dementia training, outcome data was mostly qualitative in nature, gathered by focus groups and interviewsReference Horner, Watson, Hill and Etherton-Beer29 or by staff posters.Reference Teodorczuk, Mukaetova-Ladinska, Corbett and Welfare30 The latter also measured changes in confidence using a Likert scale.

Reported outcomes: delirium education and training

Delirium knowledge

All of the studies aimed to measure delirium knowledge both before and after the intervention and to observe the changes that took place. All of the studies showed a significant increase in delirium knowledge of the participants from pre-intervention (baseline) to immediately post-intervention, apart from van de Steeg et al Reference van de Steeg, Ijkema, Langelaan and Wagner17 where changes in nurses' delirium knowledge increased but not significantly. In two studies the intervention groups had significantly higher knowledge scores than the control groups immediately after the intervention.Reference McCrow, Sullivan and Beattie15, Reference Varghese, Macaden, Premkumar, Mathews and Kumar18 McCrow et al Reference McCrow, Sullivan and Beattie15 was the only study to test knowledge at a later time after the intervention. Scores increased very slightly but not significantly between immediately post-intervention (T 2) and 6–8 weeks later (T 3) but were still significantly higher than baseline and significantly higher than the control group.

Delirium recognition

Delirium recognition was measured in four of the studies.Reference McCrow, Sullivan and Beattie15, Reference van de Steeg, Ijkema, Langelaan and Wagner17, Reference Rockwood, Cosway, Stolee, Kydd, Carver and Jarrett20, Reference Detroyer, Dobbels, Debonnaire, Irving, Teodorczuk and Fick21 Rockwood et al Reference Rockwood, Cosway, Stolee, Kydd, Carver and Jarrett20 analysed healthcare records of patients and found a significant increase (from 3% to 9% of patients) in the recording of delirium. McCrow et al Reference McCrow, Sullivan and Beattie15 used validated vignettes to test the participants' ability to recognise delirium and found that scores increased significantly between T 1 and T 2 but the significance was not maintained upon further testing at T 3. Scores were also significantly higher than the control group at T 2 but not at T 3, showing that the improvements in recognition that the intervention brought about were not maintained. van de Steeg et al Reference van de Steeg, Ijkema, Langelaan and Wagner17 found that delirium-risk screening went up from 50.8% (control group) to 65.4% in the intervention group. Detroyer et al Reference Detroyer, Dobbels, Debonnaire, Irving, Teodorczuk and Fick21 used vignettes to score delirium recognition and found an increase as a result of the intervention.

Perception of patients with delirium

Olveczky et al Reference Olveczky, Mattison and Mukamal19 measured the perception of residents (junior doctors) on general medical wards in the form of testing their ability to recall which patients had tethers (intravenous fluids, Foley catheters, telemetry) and awareness of delirium in their patients. They found a significant increase in perception scores, in particular after a 2 min in-service talk was introduced.

Quality of nurse–patient interactions

The quality of nurse–patient interactions was considered in one study.Reference Varghese, Macaden, Premkumar, Mathews and Kumar18 Nurse–patient interactions on acute medical wards were observed and scored using a checklist that had been validated by the authors. The total possible score was 100. Scores of below 50 equated to ‘inadequate practice’. The mean score of the intervention group did increase significantly from 18.28 to 37.68, this being a larger increase than in the control group. However, both pre- and post-scores for both groups indicated ‘inadequate practice’.

Reported outcomes: dementia care education and training

Dementia knowledge

Dementia knowledge was an outcome in four of the studies and was measured before and after the intervention using questionnaires that varied in quality between studies. Elvish et al Reference Elvish, Burrow, Cawley, Harney, Graham and Pilling23 found a significant increase in median score immediately post-intervention from 13.0 to 15.0 (maximum score possible 16, indicating better knowledge of dementia) and Galvin et al Reference Galvin, Kuntemeier, Al-Hammadi, Germino, Murphy-White and McGillick24 found a significant increase in average knowledge scores from 9.7 to 12.9. Galvin et al Reference Galvin, Kuntemeier, Al-Hammadi, Germino, Murphy-White and McGillick24 also measured knowledge 120 days post-intervention, finding a significant decline in one hospital but a non-significant decline in the other three. McPhail et al Reference McPhail, Traynor, Wikstrom, Brown and Quinn25 found that knowledge and understanding of dementia improved across all staff after the intervention but failed to provide full results. Instead, they provide a selection of examples of areas that staff improved on such as an increase in staff identifying pain from 25% to 44%. Ouldred & RobertsReference Ouldred and Roberts27 report that dementia knowledge was varied before the intervention with some questions being well answered by everybody and some poorly answered. However, they provide no post-intervention data because of the poor completion rate.

Dementia confidence

Two of the studies that measured knowledge also measured confidence, both finding a significant increase in confidence of staff immediately post-intervention.Reference Elvish, Burrow, Cawley, Harney, Graham and Pilling23, Reference Galvin, Kuntemeier, Al-Hammadi, Germino, Murphy-White and McGillick24 Additionally Galvin et al Reference Galvin, Kuntemeier, Al-Hammadi, Germino, Murphy-White and McGillick24 found that at 120 days post-intervention, confidence levels remained stable in three of the hospitals but declined significantly in one.

Beliefs and attitudes

Elvish et al Reference Elvish, Burrow, Cawley, Harney, Graham and Pilling23 used the Controllability Beliefs Scale to test participants’ beliefs about the controllability of behaviour that challenges. Possible scores range from 15 and 75. A higher score suggests a belief (by the respondent) that the person can control their own behaviour.Reference Dagnan, Hull and McDonnell31 Scores decreased significantly post-intervention from 27.96 to 25.85 and pointed to staff holding a more patient-centred view on challenging behaviour. Galvin et al Reference Galvin, Kuntemeier, Al-Hammadi, Germino, Murphy-White and McGillick24 evaluated participants’ attitudes and practice towards patients with dementia in hospital and found a significant improvement in attitudes in nearly all areas.

Communication techniques

One study measured the use of appropriate and inappropriate communication techniques by staff in direct contact with elderly patients with dementia.Reference Weitzel, Robinson, Mercer, Berry, Barnes and Plunkett28 It found the use of five of the appropriate communication techniques increased significantly post-intervention and three of them increased somewhat but did not reach significance. It also found that the use of inappropriate communication techniques declined, but this was not significant.

Dementia in the emergency department

One study focused specifically on dementia care training in the emergency department.Reference Ouchi, Wu, Medairos, Grudzen, Balsells and Marcus26 Following education of physicians, the study screened elderly patients in the emergency department using the FAST criteria to check for those with dementia. A total of 51 out of 304 screened patients met the criteria for advanced dementia. In total, 18 (35%) of the patients with advanced dementia received a palliative care consultation and 4 (22%) of those consultations were initiated in the emergency department. This was an increase from zero prior to the intervention. Physicians were then administered a questionnaire that showed that barriers to initiating consultation fell under the ‘physicians’ attitudes and beliefs’ category.

Reported outcomes: delirium and dementia education and training

Staff knowledge

Staff knowledge increased in both studies. In Horner et al Reference Horner, Watson, Hill and Etherton-Beer29 staff felt their increase in knowledge had led to better patient care for example trying different strategies before using medication to manage delirium. In Teodorczuk et al Reference Teodorczuk, Mukaetova-Ladinska, Corbett and Welfare30 an increase in knowledge was seen in the posters that participants produced after the 2-day course, with a deeper understanding of the experience of patients with confusion being demonstrated.

Staff self-efficacy and confidence

Horner et al Reference Horner, Watson, Hill and Etherton-Beer29 reported that staff had improved self-efficacy in distinguishing between delirium and dementia and in managing patients with delirium. Confidence in managing patients with confusion increased in Teodorczuk et al.Reference Teodorczuk, Mukaetova-Ladinska, Corbett and Welfare30

Discussion

Main findings

This systematic review focused on evidence for the provision of education and training for staff on the care and management of older patients in general hospitals who have cognitive impairment (delirium and/or dementia). A comparatively small number of papers were included in the final narrative synthesis (n = 16), revealing some evidence that educational interventions improve delirium and dementia care knowledge among staff, and generally have a positive effect on staff. However, this evidence is limited because of the wide range of interventions used and outcomes measured, as well as because of the quality of the studies included.

Importantly, none of the studies directly measured care provided or considered patient outcomes, as a result of education and training for staff, apart from seeking the perspectives of staff as to improvements in practice.Reference Horner, Watson, Hill and Etherton-Beer29 The strength of evidence to support the notion that increased knowledge translates to better staff practice and a subsequent improvement in patient outcomes for older people with delirium and dementia in general hospitals is weak. Undertaking an evaluation of education and training that includes patient outcomes presents a number of challenges including identifying not only relevant outcomes, but also those that can be measured.

Methodological considerations such as ensuring an adequate sample size to demonstrate statistical significance are also imperative. Other authors have acknowledged that patient outcomes are rarely used in the evaluation of healthcare education and training.Reference Garzonis, Mann, Wyrzykowska and Kanellakis32 This review of training for mental health practitioners found that training that focused on a particular skill, such as communication skills, was more likely to lead to positive patient outcomes, but the practitioner's ability to use and communicate knowledge was also crucial.Reference Garzonis, Mann, Wyrzykowska and Kanellakis32 Surr & GatesReference Surr and Gates33 found that changes in staff behaviour and patient outcomes are often not reported when evaluating the effectiveness of education and training on dementia care for hospital staff. A well-recognised framework for evaluating education highlights four main areas that should be considered: the reaction of learners, the extent of learning, the degree to which there has been a change in behaviour/practice change and quality of patient care.Reference Kirkpatrick34 The latter clearly comprises patient outcomes.

Selecting training intervention methods

Acceptability is an important consideration in relation to education and training interventions for delirium and dementia care but also for education and training provision more generally. A website used in one study had the benefit of allowing large numbers of people to access current information and to make learning more personal to the individual's needs.Reference McCrow, Sullivan and Beattie15 Web-based learning programmes have also been shown to lead to better performance compared with traditional instruction in a study using students in academic programmes.Reference Means, Toyama, Murphy, Bakia and Jones35 However, there are risks of a low uptake and a high attrition rate if the website is not properly advertised or engaging enough, meaning the intervention may not reach as many people as intended. Interestingly, Surr & GatesReference Surr and Gates33 recommend that independent study using e-learning is not used both because of potential problems accessing the internet and because of problems of individual motivation.

Identifying the aspect of care to be improved and preferably defining this in terms of patient outcome, is also necessary when planning education and training. None of the studies included in the review took this approach. GarzonisReference Garzonis, Mann, Wyrzykowska and Kanellakis32 has concluded that the training intervention methods should be chosen according their anticipated impact on patient outcomes. They also concluded that the training method used should be informed by the type of skill to be taught.

It is clear that baseline knowledge on the topic of delirium of healthcare professionals caring for older patients needs to be improved. A study by Inouye et al Reference Inouye, Foreman, Mion, Katz and Cooney36 found that nurses had a low sensitivity for detecting delirium, and the specific symptoms of delirium, and that it usually went unrecognised. This is backed up by other studies in this review. Varghese et al Reference Varghese, Macaden, Premkumar, Mathews and Kumar18 deemed nurses' knowledge on delirium before the intervention inadequate and their skills lacking and Meako et al Reference Meako, Thompson and Cochrane16 identified participants' inability at baseline to answer questions pertaining to delirium. This shows an intervention is essential for improving the knowledge and recognition of delirium among hospital staff.

There is no clear consensus on which outcome is the most appropriate for evaluation of educational interventions. Knowledge was the outcome measured most frequently and staff members working with patients with dementia have acknowledged that they need improved knowledge about dementia.Reference Meako, Thompson and Cochrane16 Elvish et al Reference Elvish, Burrow, Cawley, Harney, Graham and Pilling23 and Galvin et al Reference Galvin, Kuntemeier, Al-Hammadi, Germino, Murphy-White and McGillick24 both found a significant increase in knowledge scores following the intervention but McPhail et al Reference McPhail, Traynor, Wikstrom, Brown and Quinn25and Ouldred & RobertsReference Ouldred and Roberts27 did not have sufficient data to conclude that their intervention increased knowledge. The studies by Elvish et al Reference Elvish, Burrow, Cawley, Harney, Graham and Pilling23 and Galvin et al Reference Galvin, Kuntemeier, Al-Hammadi, Germino, Murphy-White and McGillick24 did not use a control group and both contained a high risk of internal bias. Therefore, despite encouraging results, we cannot say these interventions led to an increase in knowledge as confounders have not been accounted for.

Elvish et al Reference Elvish, Burrow, Cawley, Harney, Graham and Pilling23 also highlights the link between confidence and knowledge shown by Hughes et al Reference Hughes, Bagley, Reilly, Burns and Challis37 as justification to measure both in their study. Confidence scores increased significantly in both studies that measured it.Reference Elvish, Burrow, Cawley, Harney, Graham and Pilling23, Reference Galvin, Kuntemeier, Al-Hammadi, Germino, Murphy-White and McGillick24 However, improved confidence in staff does not necessarily mean improved competenceReference Hughes, Bagley, Reilly, Burns and Challis37 and as Elvish et al Reference Elvish, Burrow, Cawley, Harney, Graham and Pilling23 concludes: ‘we are largely in unknown territory regarding whether increased knowledge and confidence among general hospital staff actually improves patient care’.

Patients with dementia often receive suboptimal end-of-life care.Reference Sachs, Shega and Cox-Hayley38 Ouchi et al Reference Ouchi, Wu, Medairos, Grudzen, Balsells and Marcus26 does not provide sufficient evidence that the intervention led to an increase of emergency department initiated palliative care consultations but is useful for gaining an insight as to why patients were not offered these consultations. They concluded that ‘pre-existing beliefs, misconceptions and a lack of knowledge’ prevent physicians from initiating consultations. This highlights areas that could be targeted by future educational interventions in order to increase the initiation of palliative care consultations in turn increasing the quality of end-of-life care for older patients with dementia.

Limitations

One limitation of these review findings is that they are now out of date, the most recent search being run in September 2016. The heterogeneity of the studies included in this systematic review significantly limits its conclusions. It is difficult to summarise findings overall when the focus for studies was so diverse. There was a deliberate intention to include studies on delirium training as well as dementia care training, as much of what is considered to be good practice in care of patients is similar, such as person-centred communication; however, even when considering only studies on either delirium or dementia, heterogeneity was still present. Variability in outcomes, study populations, educational interventions and settings were evident in both the delirium and dementia care studies.

Study quality is also a limitation. Most included studies had a high risk of internal bias therefore it is difficult to say with certainty whether the improvements in the outcomes were directly because of the intervention or if other factors were involved. Methodological limitations included lack of control group, lack of masking, high attrition rate and lack of power calculation. The majority of studies (14 out of 16), were assessed as having low external validity. Limitations to external validity included unrepresentative sample sizes, unrepresentative settings and inconsistent participation rates. This means that although the results may be valid for that particular hospital or subgroup of the population, they are not generalisable. Hence, conclusions cannot be applied to the population.

Further research

Education and training interventions in the care of older people with cognitive impairment in general hospitals has hitherto attracted little research interest. Each study included in this review provides a starting point for further research in that specific area.

Additionally, there is a need for further high-quality research which considers the following:

(a) do improvements in knowledge and recognition translate to better care and management and ultimately better patient outcomes;

(b) for what period of time are improvements in staff knowledge sustained following education and training and what factors have an impact on this;

(c) is one intervention type superior to another and if so in what way and for what reason;

(d) is there a link between the demographic characteristics of participants and the impact of delirium and dementia education and training interventions?

With no mandatory dementia training in over 95% of hospitals in England39 educational interventions have the potential of filling large gaps in the knowledge and skills of staff and therefore improving patient care. This review has highlighted a lack of quality research into the effects of educational interventions and shown that further high-quality research needs to be undertaken in order to work out the best outcomes to measure following an educational intervention and to determine if the interventions lead to improved patient care and management. There is a need not only for high-quality research on delirium and dementia care educational interventions, but also for high-quality educational programmes per se, that focus on patient outcomes.

Funding

C.A. is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Academic Training Clinical Lectureship (CAT CL-2013-04-011). L.R. has an NIHR Senior Investigator Award. This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.29.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria according to PICO (initial wider review of the care and management of older patients with cognitive impairment in general hospitals)

Appendix 2 Summary of quality assessment of included studies: delirium, dementia care, dementia and delirium training

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.