It is well documented that the employment rate for individuals with severe mental illness such as schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder is unacceptably low. Reference Lehman1–Reference Waghorn, Saha, Harvey, Morgan, Waterreus and Bush5 People with severe mental illness face much greater challenges gaining and maintaining employment, owing to educational disadvantage, Reference Waghorn, Saha, Harvey, Morgan, Waterreus and Bush5 stigmatising views in the workplace, Reference Glozier6 and the chronic or recurrent nature of their mental health symptoms. In spite of this it is clear that there are numerous benefits of employment for individuals with severe mental illness. Reference Harvey, Modini, Christensen and Glozier7 Besides financial benefit, Reference Wadhell and Burton8 employment of individuals with severe mental illness is associated with improved self-esteem, Reference Lehman1 greater well-being, greater social contact and independence, Reference Bond9 and reduced use of community mental health services. Reference Bush, Drake, Xie, McHugo and Haslett10 As a result, it is not surprising that the majority of people with severe mental illness consistently report that they want to work, Reference Waghorn, Saha, Harvey, Morgan, Waterreus and Bush5,Reference Secker, Grove and Seebohm11 with mental health services often accused of not focusing enough on this aspect of recovery. Reference Harvey, Henderson, Lelliott and Hotopf12 Traditional rehabilitation models, such as clubhouse pre-vocational training and sheltered workshops, place emphasis on extensive training and preparation prior to any return to competitive (i.e. open) employment; essentially a ‘train–place’ model. Although they may be appropriate for some individuals, traditional models place little urgency around commencing immediate competitive employment (thus delaying the positive effects of employment) and may add to the sense of exclusion from mainstream society felt by many with severe mental illness. Reference Waghorn, Lloyd and Clune13 An alternative approach, known as supported employment, has been developed where the emphasis is on rapidly placing an individual into competitive employment and simultaneously providing them with support to maintain this employment; a ‘place–train’ model. Individual placement and support (IPS) is the most structured and well-defined form of supported employment. It is based on the philosophy that anyone is capable of gaining competitive employment, provided the right job with appropriate support can be identified. Reference Bond9 The core principles of IPS are defined by the IPS Fidelity Scale, Reference Bond, Becker, Drake and Vogler14 with evidence suggesting IPS is most successful when fidelity is high. Reference Bond, Peterson, Becker and Drake15 The key principles of IPS are:

-

(a) competitive employment as the primary goal;

-

(b) eligibility based on patient choice;

-

(c) integration of vocational and clinical services;

-

(d) job search guided by individual preferences;

-

(e) personalised benefits counselling;

-

(f) rapid job search;

-

(g) systematic job development;

-

(h) time-unlimited support. Reference Drake, Bond and Becker16

There have been a number of randomised trials and reviews demonstrating that IPS is effective in achieving competitive employment for individuals with severe mental illness in the USA, where this intervention originated in the 1990s. Reference Bond, Drake and Becker17–Reference Drake, McHugo, Becker, Anthony and Clark19 Two separate Cochrane reviews have provided evidence for IPS increasing rates of employment, Reference Crowther, Marshall, Bond and Huxley20,Reference Kinoshita, Furukawa, Kinoshita, Honyashiki, Omori and Marshall21 with separate studies demonstrating additional benefits in terms of job duration, hours worked per week and wages, Reference Bond, Campbell and Drake22 and decreased healthcare costs for successful users. Reference Bush, Drake, Xie, McHugo and Haslett10 Although IPS may now be seen as the ‘gold standard’ approach to mental health vocational rehabilitation in the USA, its ability to be generalised to other countries has been questioned. Reference Harvey, Modini, Christensen and Glozier7 Several of the core components of IPS, such as the need for integration between vocational and clinical services, involve organisational and cultural factors that may vary substantially between countries. Additionally, given the focus of IPS on early competitive employment, it may be more susceptible to external macroeconomic factors (such as the rate of economic growth and the availability of employment) than traditional vocational programmes. Uncertainty about the impact of these contextual factors on the effectiveness of supported employment programmes has been highlighted as a major barrier to the international implementation of IPS schemes. Reference Boardman and Rinaldi23 Although one previously published review assessed non-USA trials and suggested that IPS probably could be adopted internationally, Reference Bond, Drake and Becker24 a systematic review and meta-analysis of all the international trials of IPS, with specific consideration of the impact of different social and economic conditions, has not previously been reported.

The aim of our study was to determine whether IPS is effective in improving competitive employment rates for people with severe mental illness in different countries with varying health services and economic conditions. To the best of our knowledge this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to directly address these issues of generalisability across countries and contexts, and will, we hope, establish whether IPS can be recommended as evidence-based practice internationally.

Method

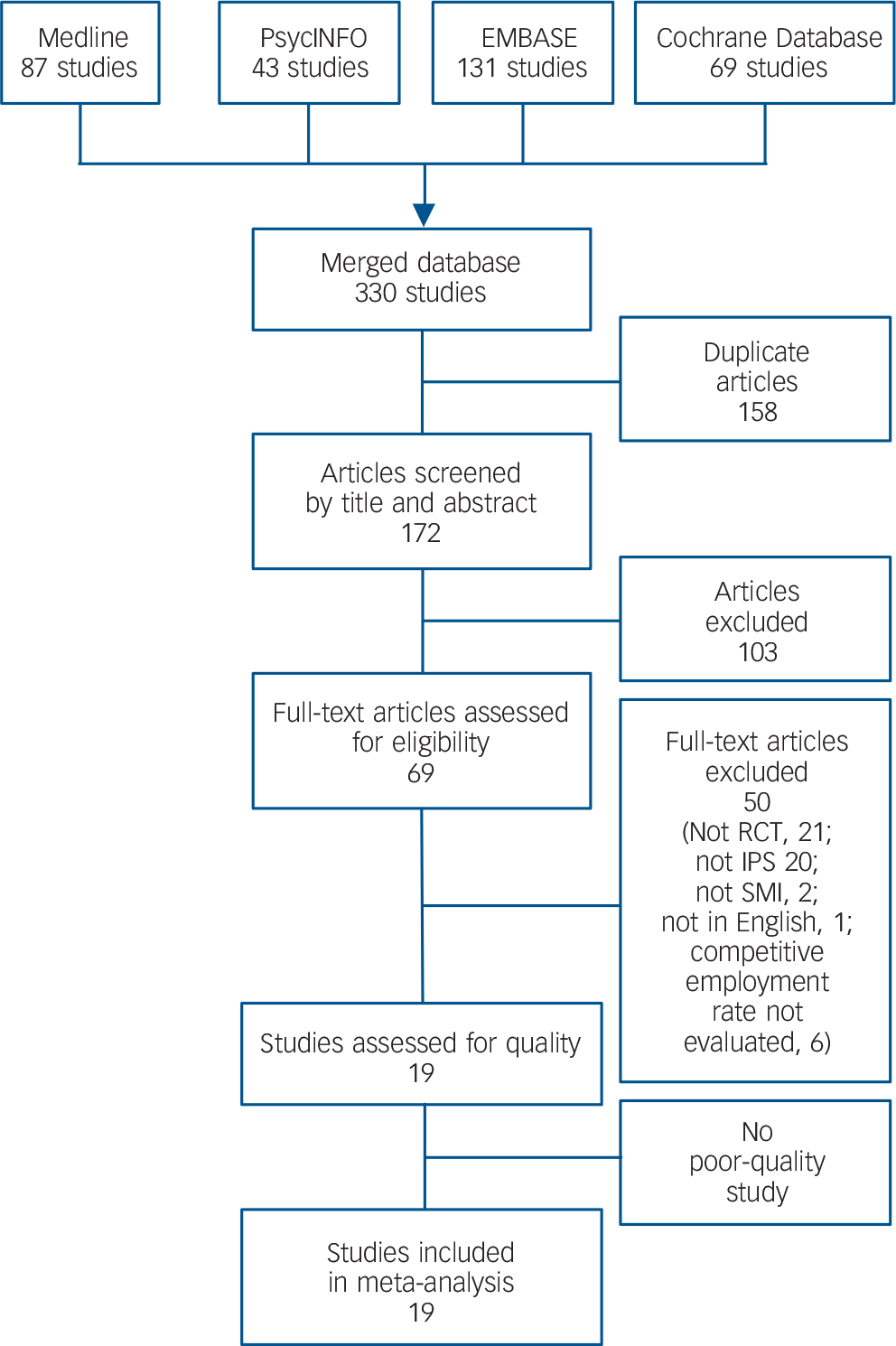

A systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (www.prisma-statement.org), using a predetermined but unregistered protocol. Searches were conducted using the electronic databases Medline, PsycINFO and EMBASE for published studies from January 1993 to January 2015. The search was restricted to studies published from 1993 onwards as, to the best of our knowledge, no study investigating IPS was reported before that year. A combination of keywords relating to severe mental illness, supported employment and randomised controlled trials was used when searching the databases. The full search strategy is shown in online Table DS1. To increase coverage an additional search using the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials was conducted using a combination of the search terms ‘individual placement and support’ or ‘supported employment’. In addition, the reference lists of all studies identified by the above strategies were scrutinised to identify any relevant publications that had not been previously considered.

A study was eligible for inclusion if it was a randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing individual placement and support with traditional vocational services; the IPS demonstrated moderate to high fidelity as measured by the IPS Fidelity Scale Reference Bond, Becker, Drake and Vogler14 or provided evidence that fidelity was adhered to; study participants had severe mental disorders, which in line with previous reviews were defined as schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like disorder, bipolar disorder or depression with psychotic features; Reference Crowther, Marshall, Bond and Huxley20,Reference Kinoshita, Furukawa, Kinoshita, Honyashiki, Omori and Marshall21 and the study was published in the English language. Papers were excluded if rate of competitive employment was not an outcome. Competitive employment was defined as a permanent job paying commensurate wages that was available to anyone (not just individuals with severe mental illness). Reference Bond, Drake and Becker24

Selection process

Two researchers independently analysed each individual title and abstract in order to exclude papers that did not meet inclusion criteria. For the remaining studies the full text was obtained and analysed independently by the two researchers to confirm the paper met the inclusion criteria. To achieve consensus, any disagreement about a study's inclusion at either stage was referred to a third researcher (S.B.H.) for consideration.

Appraisal of quality

The quality of the identified RCTs was assessed using the Downs & Black checklist. Reference Downs and Black25 This checklist demonstrates strong criterion validity (r = 0.90), Reference Olivo, Macedo, Gadotti, Fuentes, Stanton and Magee26 good interrater reliability (r = 0.75) and has previously been used in a Cochrane Collaboration review that considered mental health and the workplace. Reference Nieuwenhuijsen, Bultmann, Neumeyer-Gromen, Verhoeven, Verbeek and van der Feltz-Cornelis27 The 27-item checklist comprises five subscales that measure reporting, external validity, bias, confounding and power.

As noted by a Cochrane Collaboration review of supported employment, Reference Crowther, Marshall, Bond and Huxley20 masking of patients and treating clinicians is not possible in trials of vocational rehabilitation. It is also difficult for those evaluating outcomes to remain unaware of group allocation, as they are obliged to collect data that indicate group allocation (such as days in different types of employment). For this reason questions 14 and 15 of the Downs & Black checklist, which assess masking to the intervention allocation and outcomes, were excluded. Additionally, question 27, which assessed power, was modified in that the scoring was simplified to either 0 or 1 based on whether or not there was sufficient power in the study to detect a clinically significant effect. Thus, studies reporting power of less than 0.80 with α = 0.05 obtained a zero score. The modification of question 27 is in line with previous studies. Reference Samoocha, Bruinvels, Elbers, Anema and van der Beek28,Reference Reichert, Menezes, Wells, Dumith and Hallal29

The maximum score for the modified checklist was 26 with all individual items rated as either yes (scored 1) or no/unable to determine (scored 0), with the exception of item 5, ‘Are the distributions of principal confounders in each group of subjects to be compared clearly described?’ in which responses were rated as yes (2), partially (1) or no (0). The ranges of scores were grouped into four categories: excellent (24–26), good (18–23), fair (13–17) and poor (<12). Studies with an overall poor quality assessment were excluded from the final review. Two researchers independently assessed the quality of each included study. In order to achieve consensus, any disagreement about a study's quality rating was referred to a third researcher (S.B.H.) for consideration.

Data extraction

A single author extracted the following variables from each included study: sample characteristics, country of origin, length of follow-up and rate of competitive employment achieved for the experimental and control groups. Study authors were contacted to obtain additional information when necessary. In order to capture details on the economic situation in each country where the study was conducted, data from the World Development Indicators (World Bank) online database (http://data.worldbank.org) were used to record the annual unemployment rate and annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth for each country. The GDP is the total value of goods produced and services provided in a country annually and is often used to gauge economic growth. The average annual unemployment rate and annual GDP growth were collected when recruitment and follow-up dates of the study were available, or alternatively the average was calculated using data from the 2 years before publication date.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was conducted using competitive employment rates as the sole outcome. Competitive employment rates were scored in all included studies as a binary outcome (i.e. either achieved competitive employment or failed to do so) and thus risk ratios could be calculated. Three separate meta-analyses were conducted. The first comprised all included studies in order to determine the overall effectiveness of IPS compared with traditional vocational rehabilitation. Meta-regressions were carried out to analyse any association between IPS effectiveness and region of origin (Asia and Australia v. Europe v. North America), unemployment rates and GDP growth. The second and third meta-analyses included studies in which the follow-up data were collected after 1–12 months and 13–24 months respectively, in order to determine whether any effectiveness of IPS would remain stable over a 2-year period. The meta-analyses and meta-regressions were performed in Stata/IC release 12.1 statistical programming software using the metan and metreg commands. 30 The pooled effects were presented as risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals. The studies were weighted using the Mantel–Haenszel model. The random effects model was used because it is a more conservative approach that assumes that all studies are estimating different effects resulting from variations in factors such as study population, Reference Higgins and Green31 sampling variation within and between studies, and as a result produces wider confidence intervals. Reference Sutton, Abrams and Jones32 To test for heterogeneity Cochran's Q statistic and the I 2 statistic were reported. An I 2 value of 0% denotes no observed heterogeneity; 25% is low, 50% is moderate and 75% is high heterogeneity. Reference Higgins and Green31 Publication bias occurs when the published studies are unrepresentative of all conducted studies owing to the tendency to submit or accept manuscripts on the basis of the strength or direction of the results. Reference Dickersin33 Publication bias was determined through visual inspection of funnel plots.

Results

The detailed search in all databases identified a total of 172 titles. The title and abstract of each were examined independently by two researchers, who identified 69 articles as relevant to the research question. A further appraisal of the full text version of these articles resulted in 17 studies meeting the criteria for inclusion, Reference Drake, McHugo, Bebout, Becker, Harris and Bond18,Reference Drake, McHugo, Becker, Anthony and Clark19,Reference Bejerholm, Areberg, Hofgren, Sandlund and Rinaldi34–Reference Wong, Chiu, Tang, Mak, Liu and Chiu48 as well as 2 studies with a longer follow-up of previously analysed data, Reference Heslin, Howard, Leese, McCrone, Rice and Jarrett49,Reference Hoffmann, Jackel, Glauser, Mueser and Kupper50 resulting in 19 studies being included in this meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Where two studies used the same data source with different lengths of follow-up, we included data only from the longer or most appropriate length follow-up in each meta-analysis. One study presented data for two control groups, Reference Mueser, Clark, Haines, Drake, McHugo and Bond44 which were aggregated to form a single control group. Studies were split into geographic regions, with four studies conducted in countries in Asia and Australia, six studies in Europe and nine in North America. No additional article was identified by analysing the reference lists of the studies identified from the above strategy. Tables 1 and 2 briefly summarise characteristics of the included studies, including average unemployment rate and annual GDP growth at the time of each study; full details of the interventions are given in online Tables DS2 and DS3. None of the countries experienced negative GDP growth at the time of data collection, indicating that their economies were not in recession; however, GDP growth among the countries ranged from 0.7% to 6.6%, indicating a wide variability.

Fig. 1 Systematic literature search and quality assessment. IPS, individual placement and support; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SMI, serious mental illness.

Table 1 Summary of studies included in meta-analyses from Asian, Australian and European countries

| Study | Country | Unemployment (annual %) a |

GDP growth (annual %) b |

n | Comparison group c | Follow-up (months) |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burns et al (2007) Reference Burns, Catty, Becker, Drake, Fioritti and Knapp36 | UK | 4.8 | 3.2 | 156 | The best alternative vocational rehabilitation service available at each centre |

18 | IPS group significantly more

likely to gain competitive employment or at least 1 day (55% v. 28%) |

| Germany | 10.2 | 0.4 | |||||

| Italy | 8.2 | 0.9 | |||||

| Switzerland | 4.3 | 1.9 | |||||

| The Netherlands | 4.3 | 1.5 | |||||

| Bulgaria | 11.9 | 6.0 | |||||

| Bejerholm et al

(2015) Reference Bejerholm, Areberg, Hofgren, Sandlund and Rinaldi34 |

Sweden | 7.8 | 0.7 | 120 | TVR from various nationally run services |

18 | Significantly more IPS

participants obtained competitive employment (46% v. 11%) |

| Howard et al (2010) Reference Howard, Heslin, Leese, McCrone, Rice and Jarrett40 | UK | 5 | 2.8 | 197 | TAU | 12 | No significant difference

between IPS (13%) and TAU (7%) in obtaining competitive employment |

| Heslin et al (2011)

Reference Heslin, Howard, Leese, McCrone, Rice and Jarrett49

(follow-up study of Howard et al, 2010) |

UK | 188 | TAU | 24 | Significantly more IPS

participants obtained competitive employment v. TAU (22% v. 11%) |

||

| Hoffmann et al (2012) Reference Hoffmann, Jackel, Glauser and Kupper39 | Switzerland | 4.3 | 2.4 | 100 | TVR | 24 | Supported employment group

more likely to be competitively employed than TVR group (45.7% v. 16.7%) |

| Hoffmann et al (2014)

Reference Hoffmann, Jackel, Glauser, Mueser and Kupper50

(follow-up study of Hoffmann et al, 2012) |

Switzerland | 100 | TVR | 60 | Supported employment group

more likely to be competitively employed than TVR group (65% v. 33%) |

||

| Killackey et al

(2008) Reference Killackey, Jackson and McGorry41 |

Australia | 4.9 | 3.1 | 41 | TAU | 6 | Significantly more IPS

participants obtained competitive employment v. TAU (31.7% v 9.5%) |

| Oshima et al

(2014) Reference Oshima, Sono, Bond, Nishio and Ito45 |

Japan | 4 | 3.9 | 37 | CVR | Significantly more IPS

participants obtained competitive employment v. CVR (44.4% v 10.5%) |

|

| Tsang et al (2009) Reference Tsang, Chan, Wong and Liberman46 | Hong Kong | 6.7 | 6.6 | 163 | TVR | 15 | IPS group had better rates

of competitive employment than TVR group (53.6% v. 7.3%) |

| Wong et al (2008) Reference Wong, Chiu, Tang, Mak, Liu and Chiu48 | Hong Kong | 6.8 | 1.8 | 92 | CVR | 18 | Significantly more of the

supported employment group obtained c ompetitive employment over 12 months of follow-up compared with CVR (70% v. 29%) |

CVR, conventional vocational rehabilitation; GDP, gross domestic product; IPS, individual placement and support; TAU, treatment as usual; TVR, traditional vocational rehabilitation; TVS, traditional vocational services.

a. General population unemployment; data collected from the World Development indicators on line database.

b. Data collected from the World Development Indicators online database.

c. Details of comparison treatments are given in online Table DS2.

Table 2 Summary of studies included in meta-analyses from North American countries

| Study | Country | Unemployment (annual %) a |

GDP growth (annual %) b |

n | Comparison group c | Follow-up (months) |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond et al (2007) Reference Bond, Salyers, Dincin, Drake, Becker and Fraser35 | USA | 4.8 | 2.9 | 187 | DPA | 24 | Significantly more IPS

participants obtained competitive employment v. DPA (75% v. 33.7%) |

| Drake et al (1996) Reference Drake, McHugo, Becker, Anthony and Clark19 | USA | 6 | 3.4 | 143 | GST | 18 | Significantly more IPS

participants obtained competitive employment v. GST (78.1% v. 40.3%) |

| Drake et al (1999) Reference Drake, McHugo, Bebout, Becker, Harris and Bond18 | USA | 6 | 3.4 | 152 | EVR | 18 | Significantly more IPS

participants obtained competitive employment v. EVR (60.8% v. 9.2%) |

| Drake et al (2013) Reference Drake, Frey, Bond, Goldman, Salkever and Miller37 | USA | 8.6 | 2 | 2055 | Usual care over the 23 study sites |

24 | Significantly more

participants obtained competitive employment in supported employment v. control (52.4% v. 33%) |

| Gold et al (2006) Reference Gold, Meisler, Santos, Carnemolla, Williams and Keleher38 | USA | 4.3 | 4.5 | 143 | Gradual

work-adjusted experiences followed by placement in a ‘set-aside’ job |

24 | Significantly more IPS

participants held competitive jobs v. control (64% v. 26%) |

| Latimer et al (2006) Reference Latimer, Lecomte, Becker, Drake, Duclos and Piat42 | Canada | 7.5 | 2.1 | 149 | TVS | 12 | Significantly more in

supported employment obtained competitive employment over 12 months follow-up v. TVS (47% v. 18%) |

| Lehman et al (2002) Reference Lehman, Goldberg, Dixon, McNary, Postrado and Hackman43 | USA | 5 | 4.3 | 219 | In-house

vocational training |

24 | Significantly more IPS

participants obtained competitive employment v. control (27% v. 7%) |

| Mueser et al (2004) Reference Mueser, Clark, Haines, Drake, McHugo and Bond44 | USA | 5 | 4.3 | 204 | PSR or brokered supported employment |

24 | Significantly more IPS

participants obtained competitive employment (73.9%) v. PSR (18.2%) or brokered supported employment (27.5%) |

| Twamley et al (2012) Reference Twamley, Vella, Burton, Becker, Bell and Jeste47 | USA | 9.4 | 2.1 | 58 | CVR | 12 | Significantly more IPS

participants obtained competitive employment v. CVR (57% v. 29%) |

CVR, conventional vocational rehabilitation; DPA, diversified placement approach; EVR, enhanced vocational rehabilitation; GDP, gross domestic product; GST, group skills training; IPS, individual placement and support; PSR, psychosocial rehabilitation; TVS, traditional vocational services.

a. General population unemployment; data collected from the World Development indicators on line database.

b. Data collected from the World Development Indicators online database.

c. Details of comparison treatments are given in online Table DS3.

Two researchers independently assessed the quality of the 19 included studies. An interrater reliability of 0.74 (Cohen's kappa coefficient) was computed. Two studies were found to be of fair quality, Reference Howard, Heslin, Leese, McCrone, Rice and Jarrett40,Reference Tsang, Chan, Wong and Liberman46 and 17 studies were found to be of good quality, Reference Drake, McHugo, Bebout, Becker, Harris and Bond18,Reference Drake, McHugo, Becker, Anthony and Clark19,Reference Bejerholm, Areberg, Hofgren, Sandlund and Rinaldi34–Reference Hoffmann, Jackel, Glauser and Kupper39,Reference Killackey, Jackson and McGorry41–Reference Oshima, Sono, Bond, Nishio and Ito45,Reference Twamley, Vella, Burton, Becker, Bell and Jeste47–Reference Hoffmann, Jackel, Glauser, Mueser and Kupper50 with final assessment scores ranging from 16 to 23. No study was excluded from the meta-analyses owing to poor quality.

The first meta-analysis assessed whether IPS was effective in improving competitive employment rates for people with severe mental illness. This meta-analysis comprised all included studies with the exception of two publications, Reference Hoffmann, Jackel, Glauser and Kupper39,Reference Howard, Heslin, Leese, McCrone, Rice and Jarrett40 as other studies included in this meta-analysis analysed the same sample but with a longer follow-up period. Reference Heslin, Howard, Leese, McCrone, Rice and Jarrett49,Reference Hoffmann, Jackel, Glauser, Mueser and Kupper50 Additionally, one study was conducted in six different European countries and so the competitive employment outcome for each location was extracted and included separately in the meta-analysis. Reference Burns, Catty, Becker, Drake, Fioritti and Knapp36 Figure 2 presents the risk ratios for competitive employment in each of the 17 studies included in this meta-analysis, the pooled risk ratio for Asian and Australian, European and North American studies and the overall pooled risk ratio (PRR) using a random effects model for all included studies. The overall PRR for gaining competitive employment for IPS compared with traditional vocational rehabilitation was 2.40 (95% CI 1.99–2.90). Moderate heterogeneity was detected (Q = 62.70, I 2 = 66.5%, P<0.001). Two studies included in this meta-analysis used a sample of individuals with arguably less severe mental illness: one studied individuals with stabilised mental illness, Reference Hoffmann, Jackel, Glauser and Kupper39 and the other individuals with first-episode psychosis. Reference Killackey, Jackson and McGorry41 The analysis was re-run with these two studies excluded in order to determine whether they were positively biasing the results, but the results were almost identical to the overall analysis, with a PRR of 2.40 (95% CI 1.97–2.92).

Fig. 2 Relative risk (RR) of competitive employment for groups receiving individual placement and support (IPS) compared with standard vocational rehabilitation (RR>1 indicates greater rates of competitive employment among those receiving IPS).

Three meta-regressions were carried out to analyse any association between IPS effectiveness and geographic region (Asia and Australia v. Europe v. North America), unemployment rate and GDP growth. The meta-regressions indicated that neither unemployment rate nor geographic region significantly accounted for the heterogeneity (P>0.1 for both). However, the meta-regression for GDP growth indicated that IPS was relatively more effective in the setting of higher GDP growth (β = 0.13, s.e. = 0.59, 95% CI 0.00–0.25, P = 0.045). In spite of this trend, even when only studies carried out in the setting of relatively low GDP growth (less than 2%) were included, IPS remained more effective at gaining competitive employment, with PRR of 1.82 (95% CI 1.37–2.40).

Subsequent meta-analyses aimed to determine whether the effectiveness of IPS would remain stable over a 2-year period. Two studies were included in both these meta-analyses as data were recorded over both specified periods. Reference Tsang, Chan, Wong and Liberman46,Reference Wong, Chiu, Tang, Mak, Liu and Chiu48 Although one study presented follow-up data at 5 years, Reference Hoffmann, Jackel, Glauser, Mueser and Kupper50 only the original study presenting data at 2 years was included in the 13–24 month follow-up meta-analysis, Reference Hoffmann, Jackel, Glauser and Kupper39 to maintain consistency between follow-up rates across all studies. Figure 3 presents the risk ratios for competitive employment in each of the seven studies that had a 1–12 month follow-up period. Reference Burns, Catty, Becker, Drake, Fioritti and Knapp36,Reference Hoffmann, Jackel, Glauser and Kupper39,Reference Oshima, Sono, Bond, Nishio and Ito45–Reference Heslin, Howard, Leese, McCrone, Rice and Jarrett49 The pooled risk ratio for gaining competitive employment within the first year after IPS was commenced, compared with traditional vocational rehabilitation, was 2.59 (95% CI 1.88–3.56). Low heterogeneity was detected (Q = 7.09, I 2 = 15.4%, P = 0.31). Figure 4 presents the risk ratios for competitive employment in each of the 13 studies that had a 13–24 month follow-up period. Reference Drake, McHugo, Bebout, Becker, Harris and Bond18,Reference Drake, McHugo, Becker, Anthony and Clark19,Reference Bejerholm, Areberg, Hofgren, Sandlund and Rinaldi34–Reference Hoffmann, Jackel, Glauser and Kupper39,Reference Lehman, Goldberg, Dixon, McNary, Postrado and Hackman43,Reference Mueser, Clark, Haines, Drake, McHugo and Bond44,Reference Tsang, Chan, Wong and Liberman46,Reference Wong, Chiu, Tang, Mak, Liu and Chiu48,Reference Heslin, Howard, Leese, McCrone, Rice and Jarrett49 The pooled risk ratio for gaining competitive employment within the second year after IPS was commenced, compared with traditional vocational rehabilitation, was 2.41 (95% CI 1.96–2.97).

Fig. 3 Relative risk (RR) of competitive employment within 1–12 months of receiving individual placement and support compared with standard vocational rehabilitation.

Fig. 4 Relative risk (RR) of competitive employment within 13–24 months of receiving individual placement and support compared with standard vocational rehabilitation.

A funnel plot (online Fig. DS1) showed some mild asymmetry, indicating possible small study effects, with a tendency for estimates of the relative effectiveness of IPS to be greater among smaller studies. A sensitivity analysis was conducted excluding all studies with fewer than 100 participants. The results of this analysis were similar to the overall analysis, with PRR = 2.59 (95% CI 1.96–3.42). Separate sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine the possible effect of study quality, in particular the impact of removal of the two studies that scored ‘fair’ on the quality assessment. Reference Howard, Heslin, Leese, McCrone, Rice and Jarrett40,Reference Tsang, Chan, Wong and Liberman46 The removal of these studies did not significantly affect the overall results (PRR = 2.32, 95% CI 1.94–2.77).

Discussion

This paper represents the first published systematic review and meta-analysis specifically examining the effectiveness of IPS across a range of international and economic conditions. Our results indicate that IPS was effective in gaining competitive employment for people with severe mental illness in a wide range of settings, with individuals receiving it being more than twice as likely to gain competitive employment as those undergoing traditional vocational rehabilitation. Furthermore, the benefits of IPS can be demonstrated in a wide range of international settings regardless of the country's unemployment rate, and remained stable across a 2-year period, with similar pooled effect sizes obtained for year 1 and year 2 follow-up data. However, there is evidence that a country's GDP growth does have an impact on the relative effectiveness of IPS. Although the relative benefits of IPS were less in tough economic times, even when GDP growth was low (below 2%) IPS remained significantly more effective at gaining those with severe mental illness competitive employment compared with traditional vocational training.

Our results are in agreement with previous systematic reviews in demonstrating the overall effectiveness of IPS. Reference Crowther, Marshall, Bond and Huxley20,Reference Kinoshita, Furukawa, Kinoshita, Honyashiki, Omori and Marshall21 The key addition made by our updated systematic review and meta-analysis is a direct testing of the generalisability of IPS across different cultural and economic settings. Our finding that IPS has reduced benefit over traditional models of vocational rehabilitation when there is low economic growth is not surprising; it relies on competitive job acquisition so is likely to be more susceptible to macroeconomic factors. Given this, and the direct relationship between GDP growth and unemployment rates, it is notable that unemployment rates did not have an impact on the relative effectiveness of IPS. This may relate to GDP growth being a more sensitive measure of the overall economic condition and the employment market for those with disabilities. While noting the impact of GDP growth, the overall conclusion of the various analyses presented in this paper is that IPS is more effective than traditional models of vocational rehabilitation regardless of the prevailing cultural or economic conditions. Given this, it is important to consider barriers that might limit the international uptake of IPS as part of standard clinical practice. An editorial in the British Journal of Psychiatry summarised the key barriers to wider implementation of IPS into three categories: attitudinal barriers relating to the beliefs of both clinicians and employers; contextual factors relating to the structure of the labour market and welfare systems; and organisational factors within mental health services. Reference Boardman and Rinaldi23 One of the key organisational issues in many countries is the physical and organisational separation between disability employment and mental health services. 51 High-fidelity IPS, which appears essential for effectiveness, Reference Bond, Campbell and Drake22 is impossible to achieve without some integration between those responsible for coordination of clinical care and those directly involved in job search and occupational support. As noted earlier, uncertainty about whether IPS would remain effective in different social and economic settings may have contributed to the relative inaction in addressing some of these barriers. Reference Boardman and Rinaldi23 The results of this meta-analysis, in particular the clear evidence that IPS remains more effective than traditional vocational rehabilitation across a range of international and economic settings, allows greater pressure to be placed on policy-makers and leaders to begin addressing some of the structural and attitudinal barriers preventing wider international uptake of IPS. Better education of clinicians about employment possibilities, vocational recovery and the evidence for IPS will be important, but may need to be aided by more direct policy initiatives, such as considering employment as a key outcome measure for mental health services. Reference Boardman and Rinaldi23

At present it is not clear which of the core features of IPS are most important for its success, but it is likely that a number of factors are critical. The integration of clinical and vocational services is likely to elevate the importance of vocational outcomes within clinical teams, who might otherwise focus on symptom reduction. Second, by beginning job searches immediately, IPS challenges traditional ideas that individuals need to be totally well and free from symptoms prior to returning to the workplace. This is important because the longer individuals are out of work the less likely it becomes that they will return to work, partly owing to deterioration in skills, but more probably owing to increased feelings of anxiety and perceived vulnerability. Reference Henderson, Harvey, Overland, Mykletun and Hotopf52 Recent research within occupational medicine more broadly has confirmed the idea that individuals do not need to be symptom-free before returning to work, Reference Henderson, Harvey, Overland, Mykletun and Hotopf52–Reference Harvey and Henderson54 which has led to the implementation of schemes to encourage earlier, partial returns to the workplace, such as ‘fit notes’ in the UK. Reference Shiels, Hillage, Pollard and Gabbay55

Strengths and limitations

In order to be satisfied that there was consistency of the intervention being examined across different cultural, social and economic situations, we examined only studies that were able to demonstrate moderate to high fidelity to the IPS method. Although this is an important strength of the study and was necessary to meet our primary aim, it does limit the range of fidelity scores included and therefore precludes examination of the impact of fidelity scores on the effectiveness of IPS. Another possible moderator not directly examined was the impact of different social security systems, welfare benefits employment practice and regulation. However, included studies were from a wide variety of countries which undoubtedly have different employment and benefits practices and regulations; the fact that country of origin did not significantly account for heterogeneity provides some indirect evidence that IPS is effective in a wide range of systems, although in the future it would be useful for the role of these factors to be addressed more directly. Publication bias is an inherent issue for any meta-analysis. The funnel plot for this meta-analysis showed some asymmetry, suggesting possible small study effects. There are a number of potential causes for asymmetry in a funnel plot, including publication bias, varying methodological quality, artefact or chance. Reference Higgins and Green31 Reassuringly, a number of sensitivity analyses provided evidence against any significant small study effects, with the overall estimates of IPS effectiveness not altering substantially when all small studies were excluded. There were also some limitations within the included studies which should be highlighted. First, the length of employment deemed to be sufficient to be labelled competitive employment differed, ranging from being in employment for 1 day, Reference Burns, Catty, Becker, Drake, Fioritti and Knapp36 to being in employment for 1 month. Reference Howard, Heslin, Leese, McCrone, Rice and Jarrett40,Reference Heslin, Howard, Leese, McCrone, Rice and Jarrett49 Second, the control conditions varied among the included studies, with some being more active than others. Finally, as mentioned previously, masking of participants, treating clinicians and those evaluating outcome is often not possible in trials of vocational rehabilitation. Although this may lead to an overestimate of effectiveness, it is a problem inherent in almost all vocational rehabilitation research. Reference Crowther, Marshall, Bond and Huxley20

Study implications

This study provides strong evidence that IPS is effective in a variety of international settings, with its impact on competitive employment rates remaining for at least 2 years irrespective of economic conditions. Given these findings, policy-makers and clinicians need to begin addressing the barriers preventing wide-scale use of supported employment principles, to ensure access to high-fidelity IPS is made available to those with severe mental illness regardless of where they live or the prevailing economic conditions.

Funding

The study was funded by the Mental Health and Drug and Alcohol Office of the New South Wales Ministry of Health in Australia. The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.