St Patrick's Hospital, Dublin, was founded following a bequest by the Dean of Saint Patrick's Cathedral, Jonathan Swift, who died in 1745. Building began in 1749 and the hospital was opened in 1757. George Semple (c. 1700–1782) was the architect.

Jonathan Swift was born in Ireland in 1667 but spent a great part of his life in England. He attended Trinity College, Dublin, graduating BA in 1686. He became a minister of the Anglican Church and served in a number of parishes in Ireland before becoming Dean of Saint Patrick's Cathedral in 1713. Although he was a cleric, his major impact was in the literary field. He was a prolific author of political pamphlets, initially supporting the Whigs but shifting his support to the Tories in later life. His literary style was in irony and satire, as seen in his best known work Gulliver's Travels. In 1714 he became a Governor of Bethlem Royal Hospital in the City of London. In his final illness he experienced lethargy, loss of speech, left-sided facial palsy, swelling of the left eye and disorientation. The cause of these symptoms has been strenuously debated.

The executors of Swift's will rented the southern part of the site of Dr Steevens’ Hospital for the asylum. This choice recognised the association between mental and physical illness. Dr Steevens’ Hospital lay to the west of the city, south of the River Liffey and to the east of the Royal Hospital, Kilmainham, of 1680 for wounded and infirm soldiers. Dr Richard Steevens (1653–1710), a Dublin physician, had left a legacy in his will for the building of the hospital. His sister was his executor over many years. Work began in 1721 and the hospital, on the courtyard plan, was opened in 1733.

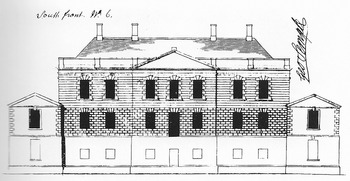

In his plans for St Patrick's Hospital, Semple drew heavily on the layout of Bethlem Hospital at Moorfields, London, of 1676, designed by Robert Hooke. At Bethlem, the wards extended on each side of the administrative block, the galleries facing north and the cells south. At St Patrick's, the administrative block faced south, was of seven bays with a plain balustrade, the centre three bays being advanced and surmounted by a pediment. The building was constructed of grey granite, rusticated in the ground floor and strongly incised in the first floor. From the entrance hall an elegant curved cantilevered staircase rose to the first floor. The two ward blocks extended behind and at right angles to the façade of the administrative building. The ward blocks were of two stories, each providing 16 individual cells for patients, together with a basement, which accommodated a smaller number of patients. Each cell had a high, barred opening on one side to provide ventilation and on the other side opened through a stout doorway on to a wide corridor or gallery which was used for recreation. The galleries faced each other across a small courtyard. The windows of the galleries were small, giving inadequate light, but were later enlarged. Some of the windows were glazed and some had shutters. Later, day-rooms were added, which allowed some segregation of patients according to need. The drains and heating were problematic over many years. By 1762 the hospital had 78 eight beds.

In 1778 Thomas Cooley enlarged the accommodation for patients. He lengthened the existing wards to the north and added small wings to the administrative block (Fig. 1). These additions increased the number of beds to 132. There were many later additions to the hospital. In her book Swift's Hospital, Elizabeth Malcolm describes recurring problems: in the management of the estate, with finance, in contracts with suppliers, maintenance of the buildings, staff discipline, modernising the hospital and in dealing with these matters in compliance with the Founder's wishes. Swift's legacy was too small to sustain a purely charitable hospital and this led to the admission of paying patients.

Fig. 1 The elevation of the front of the hospital, signed by the architect George Semple. Reproduced from Elizabeth Malcolm's book, Swift's Hospital: A History of St Patrick's Hospital, Dublin, 1746–1989, with permission of the publishers Gill & Macmillan.

Throughout its long life the hospital has occupied a prominent position in the care of the mentally ill in Ireland and more recently in teaching and research in association with Trinity College, Dublin.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.