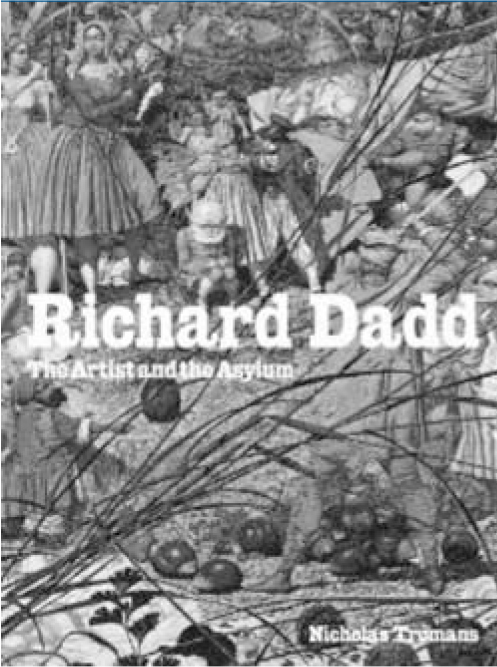

The story of Richard Dadd is well known to historians of art and madness. He was the promising young Victorian artist who, believing his father was Satan, murdered him and subsequently spent the rest of his life in the criminal lunatic departments of Bethlem and Broadmoor, where he continued to paint and to produce works that were arguably more compelling than those he completed before he developed psychosis. In this new and splendidly illustrated book, Nicholas Tromans, an art historian at Kingston University, London, provides a thoughtful and balanced commentary on the Dadd story, which draws on the past three decades of research in the history of psychiatry to create a nuanced and in-depth picture of the 19th-century parricide. Tromans looks at the relationship between madness and creativity, the nature of Dadd's mental disturbance and his time in the asylum.

Some artists stop being creative when they develop psychosis; some, like the ‘schizophrenic masters’ in the Prinzhorn collection, only start painting after they go mad. Dadd's case is rather different. His remarkable technical skills were unaffected by his descent into mental illness and, indeed, in The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke and Contradiction: Oberon and Titania, he made pictures of more complexity than those of his pre-asylum days. What, if any, was the impact of psychosis on his art? Tromans is rightly sceptical of previous attempts to identify stylistic characteristics of ‘psychotic art’, such as obsessive pattern-making, which, in any case, Dadd's work does not display. Instead, he suggests that Dadd lacked a capacity to see the world from other people's point of view. Certainly, the few surviving transcriptions of Dadd conversations reveal that he saw himself as a superior individual who inhabited a higher, spiritual domain, unbound by the rules of ordinary humanity. Ironically, before he became mentally ill, Dadd affected the then-fashionable pose of the artist as Byronic ‘madman’. As Tromans observes, such a pose offered an artist the opportunity to parade his supposedly unconventional and ‘interesting’ persona without actually suffering the blight of insanity.

So what was wrong with Richard Dadd? As the former Bethlem archivist Patricia Allderidge has previously shown, the asylum case note record of Dadd is disappointingly sparse. We know that on 28 August 1843, Dadd stabbed his father to death. Having obtained a passport before the murder, he fled by boat to France with the intention, he later claimed, of assassinating Ferdinand I, the Emperor of Austria. Instead, while travelling in a coach near the Forest of Fontainebleau, he attacked a fellow passenger with a razor, stating that he had received a ‘message’ from the stars instructing him to do so. Dadd believed that his true father was the Egyptian god Osiris and that the man who brought him up was an impostor and most probably the Devil. In court, Dadd claimed he was merely ‘the cat's paw’ in an ‘act of volition’, which could not be attributed to him, though he approved of the murder. He was initially admitted to Clermont Asylum north of Paris, before being transferred to Bethlem Asylum. In 1854 Dr Charles Hood, physician superintendent of the Bethlem, summarised Dadd's case:

‘For some years after his admission he was considered a violent and dangerous patient, for he would jump up and strike a violent blow without any aggravation, and then beg pardon for the deed. This arose from some vague idea… that certain spirits have the power of possessing a man's body and compelling him to adopt a particular course whether he will or no’ (p. 195).

From these sketchy details, most psychiatrists, if they were inclined to engage in retrospective diagnosis, would probably conclude that Dadd suffered from schizophrenia. Tromans remarks that Dadd received very little in way of ‘treatment’, if one wanted to defend the asylum, one could say that it both protected the general public from a dangerous patient and provided Dadd with the facility to continue his work as an artist. Tromans notes that interest in Dadd has fluctuated over the years. After a long period of obscurity in the first half of the 20th century, Dadd enjoyed something of a revival in the 1960s when it seemed that he was on the verge of being recruited as a hero of counterculture, the mad artist whose work was a visionary riposte to the bourgeois order. Although Tromans is at pains to emphasise that he does not see Dadd as any kind of hero, it is to be hoped that his book and the astounding, high-quality reproductions that illustrate it, will inspire renewed interest in the work of this gifted if disturbing Victorian artist.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.