The way we respond to a problem is shaped by how we frame and describe it. The treatment gap is defined as the proportion of people who meet diagnostic criteria for a given disorder whose condition is untreated.Reference Kohn, Saxena, Levav and Saraceno1 This concept, anchored to the twin claims that mental disorders are highly prevalent and that mental health services are scarce, has been a central tenet of the discipline of global mental health (GMH). Treatment gaps ranging from 82 to 98% have been reported for common mental disorders (CMD),Reference Wang, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Angermeyer, Borges and Bromet2 with these figures typically higher among communities that are marginalised or have fewer resources.

The 2007 and 2011 Lancet GMH seriesReference Chisholm, Flisher, Lund, Patel, Saxena and Thornicroft3,Reference Patel, Boyce, Collins, Saxena and Horton4 argued that the central mission of the field is to scale up evidence-based care in order to ‘close the treatment gap’ for mental disorders, of which the most prevalent are CMD (defined as depression, anxiety and somatoform disorders). These arguments are mirrored in key World Health Organization publications, which place ‘closing the treatment gap’ front and centre of international mental health policy.5 Recent literature demonstrates how pervasive this concept continues to be in shaping the narrative of the field, with many articles still framing findings in terms of the treatment gap for mental disorders.Reference Fuhr, Acarturk, McGrath, Ilkkursun, Sondorp and Sijbrandij6

However, there has been much critique of the evidence base for this gap, from arguments that the measures used ignore important local variation in conceptualisations of mental distressReference Ingleby7 to those that draw attention to the broader needs of people with mental illnesses.Reference Pathare, Brazinova and Levav8 In response, the 2018 Lancet CommissionReference Patel, Saxena, Lund, Thornicroft, Baingana and Bolton9 replaced ‘treatment gap’ with the ‘care gap’, referring to the unmet mental health, physical health and social care needs of people with mental illness.Reference Pathare, Brazinova and Levav8 However, we contend that maintaining the notion of a ‘gap’ misses a more fundamental point: why do so few people access mental health treatment? And how does this influence how we conceptualise solutions to the lack of service uptake?

In this analysis, we consider a frequently overlooked contributor to the treatment gap: low demand for services arising from non-medical interpretations of CMD-related experiences – and its implications for how we respond to the needs of people who are considered to suffer from CMD. Our arguments are written from the position of allyship or lived experiences of adversity: three of our authors were born in, or are direct descendants of, communities who face the structural determinants of poor mental health that are largely overlooked in this field. All the authors have devoted their academic careers to advancing arguments that create meaningful space for the contexts of mental health to be taken more seriously. We argue that although providing appropriate services that consider the social and economic realities of people's lives is essential, global mental health must also advance a movement for improved public mental health measures targeting the structural and political determinants of mental health.

Our focus in the current piece is on CMD because this is frequently the target of GMH initiatives, and the majority of people in the ‘mental health treatment gap’ are those considered to have CMD. Some of our argument will apply to other categories of mental disorder but exploring the extent to which it does is beyond the scope of this analysis.

Supply or demand?

The treatment gap is often taken to indicate a shortage of mental health services; in other words, a problem of supply, supported by evidence of resource deficits for mental healthcare. This is used to justify focusing on increasing access to mental health services, particularly in settings where resources are most scarce.

However, there is also evidence to suggest an alternative interpretation. The World Mental Health Surveys, conducted in 24 countries with 63 678 participants, found that lack of perceived need for treatment was by far the most frequently reported reason given for not seeking treatment for mental health problems.Reference Andrade, Alonso, Mneimneh, Wells, Al-Hamzawi and Borges10 This is consistent with the hypothesis that many people who fall in the ‘treatment gap’ do not want treatment for their depression or anxiety symptoms. This alternative interpretation (the treatment gap as a demand rather than supply issue) was borne out in the PRIME programme – an 8-year initiative to increase the supply of mental health services in five low- and middle-income countries – which demonstrated that, in the absence of demand, increasing the supply of mental health services does not reduce the treatment gap for CMD .Reference Shidhaye, Baron, Murhar, Rathod, Khan and Singh11 However, explaining the reasons behind the lack of demand for mental health services has received scant attention in the global mental health literature.

Why is demand for mental healthcare so low?

Low demand for mental health services is typically attributed to stigma, barriers to access such as travel costs, limited ‘mental health awareness’ or limited service provision.Reference Patel, Saxena, Lund, Thornicroft, Baingana and Bolton9 Although these may contribute to low service uptake, our research offers a simpler explanation that has received less attention. Our findings indicate that across multiple low-resource settings in both the global north and south, people fail to seek mental health services – and disengage from services – because people interpret their psychological and emotional states as reactions to social and economic problems, not as health conditions that can be addressed by medical services. Similar findings have been reported in both low- and middle-income countries and among marginalised groups in high-income settings.

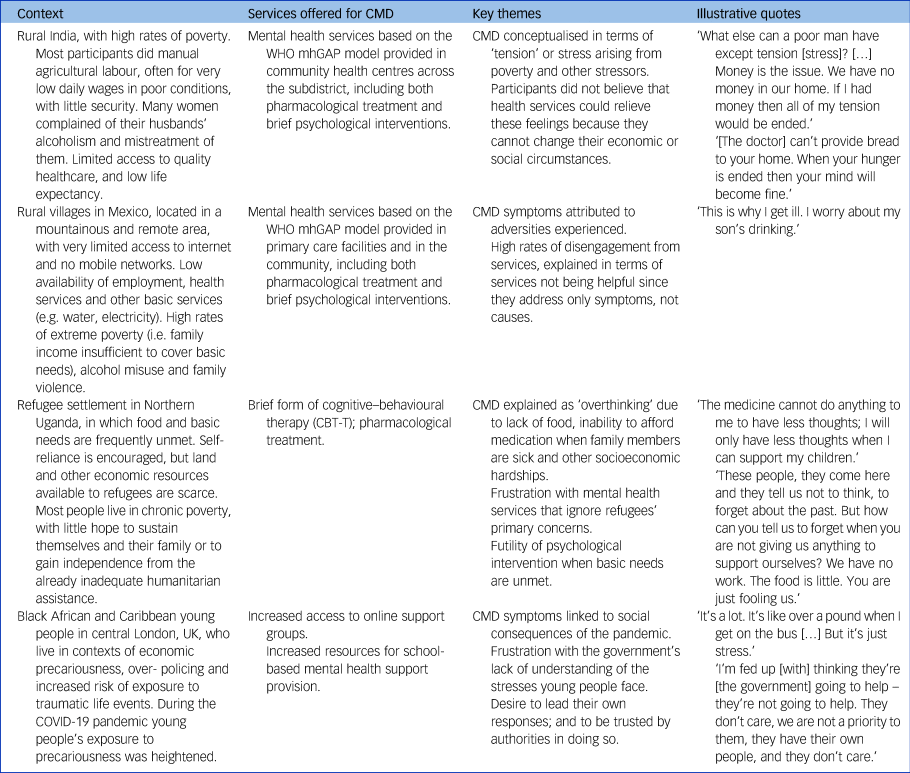

In Table 1 we summarise findings from four qualitative studies.Reference Roberts, Shrivastava, Koschorke, Patel, Shidhaye and Rathod12–Reference Burgess, Kanu, Matthews, Mukotekwa, Smith-Gul and Yusuf15 The research cited adds to the evidence base that decontextualised approaches to mental health treatment make little sense to people whose psychological distress is linked to ongoing adversity. By ignoring the social determinants that frequently cause psychological distress, mental health services often fail to meet people's perceived needs, resulting in low uptake and high drop-out rates when these services are rolled out, despite positive results in trials. Many people do not believe that psychological or pharmacological treatment will make them feel better if their basic needs remain unmet. Indeed, ‘feeling better’ on its own is rarely people's primary goal, when understood solely as a psychological experience; to feel better, people need to see real change in their circumstances.

Table 1 Summary of qualitative research from India, Mexico, Uganda and the UK exploring reasons for low engagement with mental health services for common mental disorders (CMD)Reference Roberts, Shrivastava, Koschorke, Patel, Shidhaye and Rathod12–Reference Burgess, Kanu, Matthews, Mukotekwa, Smith-Gul and Yusuf15

WHO mhGAP, World Health Organization's Mental Health Global Action Programme.

To be clear, we are not advocating the abandonment of mental health treatment. However, to ensure demand for services, community concerns and potential solutions must be central to the design and delivery of mental health programmes. This can be achieved through participatory action research or co-production with potential patients.Reference Campbell and Burgess16 However, this may require a fundamental rethink of interventions and their method of implementation: the resulting interventions may not look like mental health services as conceptualised by the health sector (Appendix).

Don't we just need more mental health awareness?

With low mental health literacy often blamed for low demand for mental health services, efforts to raise awareness have been increasingly mainstreamed in mental health programmes. Calls for awareness campaigns to change the community's current understanding of CMD may be misguided, however, not only because the principles of person-centred care recommend listening to patients and adapting services to their needs (rather than convincing patients that their needs should match the services offered), but also because a growing evidence base suggests that people facing ongoing adversity are indeed less likely to respond to treatment, in the absence of a change in their circumstances. Two recent systematic reviews provide preliminary evidence that both psychological and pharmacological treatments for depression are less effective for people living in greater deprivation.Reference Finegan, Firth, Wojnarowski and Delgadillo17,Reference Elwadhi and Cohen18 Most of the evidence reviewed was from high-income countries, but in a CMD intervention trial in Goa, participants facing major current life problems were also far more likely to remain depressed despite treatment.Reference Patel, Weiss and Mann19

Given the extensive evidence on the social determinants of mental health, it should be unsurprising that trying to improve patients’ mental health while the causes of the problem are ongoing frequently fails. Treating people and sending them back to the same conditions that made them sick is a Sisyphean task. This may go some way towards explaining the lack of association observed between mental health service coverage and prevalence of CMD.Reference Jorm, Patten, Brugha and Mojtabai20

A route forward for global mental health

Arguments thus far illuminate why a treatment gap is a poor measure of unmet need, and GMH must move beyond ‘closing the treatment gap’ – at least for CMD – as its primary goal. Although there is a human rights case for improving access to and quality of mental healthcare for those who want to use formal services, scaling up these services without wider social and economic measures will not necessarily reduce the overall burden of mental ill health.Reference Jorm, Patten, Brugha and Mojtabai20 We need upstream approaches, including social and economic interventions to reduce the causes of mental ill health, to make a meaningful impact on population mental health, especially for deprived or marginalised communities. In other words, in addition to a health sector response, we require a societal response to the causes of CMD that lie beyond the health sector.

We therefore propose an explicit distinction between two separate agendas in GMH, based on distinct rationales:

(a) service improvement, based on human rights, co-production and quality improvement principles

(b) a prevention agenda to reduce the population burden of mental disorders through action on the social, structural and political determinants of mental health (reflecting the explanatory models of people who attribute their CMD symptoms to their social and economic circumstances).

Importantly, these recommendations apply not only to low- and middle-income countries but also to high-income settings, particularly for marginalised groups who are most negatively affected by the structural determinants of mental health and who are least likely to access formal mental healthcare.

Reforming services

The development of effective and culturally appropriate interventions for CMD that can be implemented in low-resource settings, such as the Thinking Healthy intervention in PakistanReference Rahman21 or the Friendship Bench in Zimbabwe,Reference Chibanda, Weiss, Verhey, Simms, Munjoma and Rusakaniko22 has been an important step towards providing appropriate support to people experiencing CMD symptoms. However, the limits of what these interventions can achieve in the absence of social and economic change must be acknowledged, as well as the disparity between the service that is delivered in randomised controlled trials and that which is typically delivered in routine services to those who seek help for CMD.

Although the GMH agenda has placed great emphasis on expanding services to reach all those who meet diagnostic criteria for CMD, many of whom do not consider themselves to need or want such treatment, the quality of care received by the minority of those who do seek treatment – typically those with more severe symptoms – is still frequently poor. We contend that rather than ‘closing the treatment gap’ through identifying more non-treatment-seeking individuals with CMD, improving the quality of care for those who currently seek help should be a priority.

Poor-quality healthcare and struggling health systems limit the extent to which it is possible to deliver effective interventions to those with CMD, particularly those living in vulnerable situations.Reference Kruk, Gage, Arsenault, Jordan, Leslie and Roder-DeWan23 Basic problems such as lack of healthcare personnel, inadequate facilities and shortage of medications still affect a large proportion of the world's population and make it extremely difficult to offer person-centred care through health services. To fulfil the right to health for all, we need health systems that are adequately resourced and designed to address contextual challenges. Persuading more people to seek help for CMD when health services are unable to provide quality care may be counterproductive; our first priority should be to advocate for investment in systems strengthening so that those who do receive treatment receive high-quality and dignified care.

Furthermore, our goal in terms of increasing access to services must be not only that the human right to care is met, but also that people have the ability to improve their lives in ways they consider meaningful. Achieving this is only possible by actively involving communities and those who seek care in the design and evaluation of services and working collaboratively to build solutions with the families and communities that these services serve.Reference Campbell and Burgess16 Such methods ensure greater attention to demand-side barriers – which are often strongly interlinked with the social and economic contexts of people's lives – to create services that people want to engage with.

Upstream interventions to tackle social determinants of mental health

Although good-quality treatment for the minority who want it is important, when it comes to the extensive ‘social suffering’Reference Campbell and Burgess16 experienced by many people with CMD, individual-level treatment is not the answer to failed social systems. Improving population mental health will require improvements in the social conditions that give rise to social suffering. This is referred to as tackling the ‘prevention gap’,Reference Patel, Saxena, Lund, Thornicroft, Baingana and Bolton9 but has thus far received scant attention in the GMH literature. We contend that this stream of GMH requires far greater concerted efforts than it has received to date. It is through this stream, by contributing to collective efforts to advocate for structural changes, that substantive gains can be made in reducing the mental health burden of populations.

In this analysis we make clear the need to bring intervention efforts more in line with voiced concerns of people living through adversity globally. Elsewhere we have suggested models to bring us closer to a field where upstream and downstream approaches work in parallel to respond to social determinants of poor mental health.Reference Campbell and Burgess16,Reference Burgess, Jain, Petersen and Lund24 We welcome recent modelling and quantitative evidence that confirms what has been said for decades by the people who live through adversity and seek to maintain good mental health: that the sociostructural conditions of everyday life matter.

The evidence base for the mental health impact of policies and interventions to address social determinants originates disproportionately from high-income settings in Western Europe, North America and Australasia, and public mental health research is urgently needed that is relevant to other contexts. This will require a different set of research tools from those traditionally employed in GMH, since upstream interventions are not always amenable to randomised controlled trials.

Conclusions

In summary, we believe that ‘closing the treatment gap’ for CMD should be revised as a goal of global mental health. We maintain that recent evidence suggests that the treatment gap for CMD also reflects lack of demand for mental healthcare because symptoms are explained in social or economic terms, mirroring known social determinants of mental health. A growing evidence base also suggests that people with CMD who face adversity are right to doubt the utility of treatment without a change in their social or economic circumstances. Providing interventions that address people's mental health needs is central to global mental health, but ‘treatment’ per se does not necessarily meet these needs. We must therefore expand the notion of what constitutes a mental health intervention. It is important to acknowledge two divergent agendas within global mental health – (a) public mental health and (b) increasing access to and quality of healthcare – which require different skills, strategies, stakeholders and research agendas. We contend that greater transparency about these two parallel streams, and support for the often overlooked public mental health field, is necessary for the field to progress.

Data availability

No new data were created or analysed in this study. The research referenced in Table 1 is reported elsewhere and the supporting data from these studies are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author contributions

T.R., G.M.E. and C.T. conceptualised the analysis and T.R. was responsible for drafting the manuscript. P.P., A.C. and R.A.B. subsequently provided critical feedback and suggested edits and additions to the text. T.R., G.M.E., C.T., P.P. and R.A.B. all provided illustrative examples of the phenomenon discussed from their own research.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. However, T.R. is supported by an Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) post-doctoral fellowship (ES/T007125/1).

Declaration of interest

None.

Appendix

Project Burans is a partnership project working with communities to improve mental health in Uttarakhand, North India. The case study presented below describes how social and economic considerations can be incorporated into interventions for common mental disorders (CMD).

Rajini is a woman in her 30s who lives with her single mother in a slum near the bustling tourist town of Mussoorie in North India. Her mother is the sole breadwinner in the family and they are barely making ends meet. Rajini was diagnosed with CMD and has been confined to her house for most of her adult life because of these difficulties.

A Burans community worker worked with the pair for 4 months, not only looking at the biomedical aspect of Rajini's recovery, but also working through the social aspects, including keeping busy and trusting her with responsibilities. Rajini was enrolled in a 3-month recovery-oriented care plan. Alongside counselling, the community worker contacted a chicken vendor, with the idea that caring for chickens would give Rajini purpose while easing the financial burden of the family.

This simple and sustainable programme has shown surprising results. Rajini gets up early every day, freshens up and takes care of the chicks. Her mother says ‘If each hen gives one egg every 3 days at 10–15 rupees per egg, then we will have a supplementary income. The best part of this has been seeing my daughter take up this responsibility. I never thought I would see this day.’

This story of change has helped the Burans team realise the importance of livelihood interventions to support families, but also the impact of working on social determinants to improve mental health, apart from the biomedical services available.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.