Antipsychotic treatment plays a critical role in alleviating the acute symptoms of schizophrenia and maintenance treatment is routinely recommended to prevent re-emergence/exacerbation of symptoms (i.e. relapse). Reference Takeuchi, Suzuki, Uchida, Watanabe and Mimura1 For example, a recent meta-analysis conducted by Leucht et al, including 64 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), provides compelling evidence that antipsychotic maintenance treatment is superior to placebo in reducing the risk of relapse in stable schizophrenia. Reference Leucht, Tardy, Komossa, Heres, Kissling and Salanti2 That said, definitions of relapse differ substantially between investigations, Reference Gleeson, Alvarez-Jimenez, Cotton, Parker and Hetrick3 which in turn compromises validity when directly comparing multiple studies. This has been noted in Leucht et als meta-analysis, Reference Leucht, Tardy, Komossa, Heres, Kissling and Salanti2 in addition to others comparing efficacy for relapse prevention between first-(FGAs) and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) Reference Kishimoto, Agarwal, Kishi, Leucht, Kane and Correll4 as well as oral and long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics. Reference Kishimoto, Robenzadeh, Leucht, Leucht, Watanabe and Mimura5 In the context of data aggregation, total scores (i.e. a continuous variable) on clinical rating scales such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler6 and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) Reference Overall and Gorham7 provide a more generalisable outcome than relapse, a dichotomous variable that can vary one definition to the next. There have been several meta-analyses Reference Agid, Kapur, Arenovich and Zipursky8–Reference Sherwood, Thornton and Honer11 using PANSS or BPRS total scores, although all have investigated the onset of antipsychotic action or time course of symptom change during antipsychotic treatment in the acute phase of schizophrenia. To date, none has compared symptom trajectories between antipsychotic and placebo treatments in the maintenance phase.

Accordingly, the following question relating to maintenance treatment of schizophrenia remains unanswered: is antipsychotic treatment superior to a placebo replacement in terms of symptom trajectories in the maintenance phase of schizophrenia? To address this clinical question, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs comparing symptom trajectories between antipsychotic and placebo treatments in stable patients with schizophrenia.

Method

Literature search and study selection

Our clinical question built upon the meta-analysis conducted by Leucht et al. Reference Leucht, Tardy, Komossa, Heres, Kissling and Salanti2 Their meta-analysis included 64 RCTs with treatment arms consisting of an antipsychotic(s) along with placebo or no treatment, in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (i.e. schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and/or schizophreniform disorder) who had been stabilised on antipsychotics. From these 64 studies, we selected those that met the following additional eligibility criteria: (a) studies using the PANSS or BPRS; (b) studies reporting the PANSS or BPRS total scores at both baseline and another time point, at minimum; and (c) studies using a last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) method.

Considering that Leucht et al performed their literature search several years ago, we conducted a systematic literature search (last search: 19 January 2016), using the MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) with a limitation of year (i.e. from 2011 to current) in order to update the search. We adopted the same search strategy used by Leucht et al Reference Leucht, Tardy, Komossa, Heres, Kissling and Salanti2 including keywords ((cessation* OR withdraw* OR discontinu* OR halt* OR stop* OR drop-out* OR dropout* OR drop out OR rehospitalis* OR relaps* OR maintain* OR maintenance* OR recur*) AND (schizophr* OR schizoaff*)) and a limitation (‘randomized controlled trial’). Two authors (H.T. and N.K.) independently conducted the literature search in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) statement. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman12 We selected studies that met the following eligibility criteria: (a) original studies (i.e. not protocols, reviews, meta-analyses or secondary analyses); (b) RCTs; (c) studies including treatment arms of both an antipsychotic(s) and a placebo or no treatment; (d) studies where > 70% of participants were diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders; (e) studies including only patients with stable psychopathology; (f) studies using the PANSS or BPRS; (g) studies reporting the PANSS or BPRS total scores at both baseline and another time point, at minimum; and (h) studies using an LOCF method. Risk of bias for each included study was assessed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Reference Higgins and Green13

Data extraction

The PANSS or BPRS total scores were collected for each study for up to 52 weeks from randomisation; weekly for the first 4 weeks and at 4-week intervals thereafter. In order to utilise as much data as possible, values not lining up with the 4-week intervals were moved forward to the next 4-week value (i.e. a value at 4n weeks + 2 weeks was recorded as a value at 4(n + 1) weeks). Data presented in graph-form were extracted automatically using an online computer program (Dexter; German Astrophysical Virtual Observatory, University of Heidelberg, Germany; available at http://dc.zah.uni-heidelberg.de/dexter/ui/ui/custom); for the one case in which the software could not retrieve the data, it was extracted manually instead.

Data analysis

Standardised total scores were calculated by dividing the PANSS or BPRS total scores by the number of items (i.e. 30 items for PANSS and 18 items for BPRS) and used as a primary outcome. Per cent score changes were also calculated using the following formulation Reference Leucht, Davis, Engel, Kane and Wagenpfeil14–Reference Leucht, Kissling and Davis16 as a secondary outcome: (PANSS or BPRS total score at a given time-PANSS or BPRS total score at baseline)/(PANSS or BPRS total score at baseline – 30 for PANSS or 18 for BPRS) × 100.

To compare standardised total scores and per cent score changes over time between the two treatment groups (i.e. continuing antipsychotics and switching to placebo), meta-regression analyses were employed with a mixed model that included baseline scores as a covariate Reference Furukawa, Levine, Tanaka, Goldberg, Samara and Davis17 (none for per cent score changes), group, time and interaction between group and time as fixed effects. In order to allow for a flexible model rather than specific functional forms such as linear and quadratic, a fixed effect of time in weeks was specified as a categorical predictor. The model also included a random time slope and a random intercept, with covariance matrix structure between random effects specified as unstructured. The number of participants at baseline was used as regression weights in the analysis as we only included studies using an LOCF method. The estimation method for mixed-effect models was restricted maximum likelihood. This method is in accordance with a previous meta-analysis examining symptom trajectories during antipsychotic treatment in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Reference Suzuki, Remington, Arenovich, Uchida, Agid and Graff-Guerrero10

As sensitivity analyses, the following studies or arms were excluded from the analyses: studies using BPRS; LAI treatment arms; FGA treatment arms, low-dose antipsychotic treatment arms defined as ⩽80% of daily defined dose (DDD; available at http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index); placebo treatment arms where participants had been treated with LAI antipsychotics before randomisation; or, studies with a high baseline PANSS or BPRS score because of the criteria for symptom stabilisation (see Table 1 and online Table DS1). A two-tailed P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests. All statistical analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS Statistics version 21.

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies a

| Antipsychotic arm | Control arm, placebo | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (years) | Scale | Duration, weeks |

Intervention | Formulation | Dosing | Mean dose, mg/day or month |

n c | Men n (%) |

Mean age years |

Mean illness duration years |

Mean baseline total score |

n c | Men n (%) |

Mean age years |

Mean illness duration years |

Mean baseline total score |

| Arato et al

Reference Arato, O'Connor and Meltzer18

(2002) |

PANSS | 52 | Ziprasidone | Oral | Fixed | 40 | 71 d | 52 (72) | 50.8 | 22.9 | 84.2 | 71 | 59 (83) | 48.7 | 21.7 | 88.4 |

| Ziprasidone | Oral | Fixed | 80 | 68 | 48 (71) | 49.8 | 20.7 | 86.2 | ||||||||

| Ziprasidone | Oral | Fixed | 160 | 67 | 44 (66) | 49.6 | 22.0 | 84.5 | ||||||||

| Beasley et al

Reference Beasley, Sutton, Hamilton, Walker, Dossenbach and Taylor19

(2003) |

PANSS | 30 b | Olanzapine | Oral | Fixed (10/15/20 mg/day) |

13.4 | 224 | 119(53.1) | 36.2 | 11.3 | 42.2 | 100 d | 54 (52.9) | 35.1 | 10.7 | 43.1 |

| Clark et al

Reference Clark, Huber, Hill, Wood and Costiloe20

(1975) |

BPRS | 24 | Pimozide | Oral | Flexible | 5.3 | 15 | 0 | 42.5 | 12.3 | 28.6 | 10 | 0 | 42.1 | 11.3 | 30.8 |

| Thioridazine | Oral | Flexible | 188.8 | 15 | 0 | 43.5 | 11.0 | 28.0 | ||||||||

| Cooper et al

Reference Cooper, Butler, Tweed, Welch and Raniwalla21

(2000) |

BPRS | 26 | zotepine | Oral | Fixed (300/150 mg/day) |

NA | 61 | 40 (65.6) | 43.0 | 13.9 | 49.8 | 58 | 42 (72.4) | 41.6 | 13.16 | 48.4 |

| FU et al

Reference Fu, Turkoz, Simonson, Walling, Schooler and Lindenmayer22

(2015) |

PANSS | 64 | Paliperidone | LAI | Fixed(50/75/100/ 150mg/month) |

114.4 (monthly) |

164 | 85 (51.8) | 39.3 | NA (64.0% >5 years) |

51.1 | 170 | 84 (49.4) | 38.0 | NA (64.7% >5 years) |

51.8 |

| Hough et al

Reference Hough, Gopal, Vijapurkar, Lim, Morozova and Eerdekens23

(2010) |

PANSS | Variable b | Paliperidone | LAI | Fixed (25/50/100 mg/month) |

82.8 (monthly) |

205 | 109 (53) | 38.8 | NA | 52.1 | 203 | 111 (55) | 39.4 | NA | 53.1 |

| Kane et al

Reference Kane, Sanchez, Perry, Jin, Johnson and Forbes24

(2012) |

PANSS | 52 b | Aripiprazole | LAI | Fixed (400/300 mg/month) |

396.3 (monthly) |

269 | 162 (60.2) | 40.1 | NA | 54.5 | 134 | 79 (59.0) | 41.7 | NA | 54.4 |

| Kramer et al

Reference Kramer, Simpson, Maciulis, Kushner, Vijapurkar and Lim25

(2007) |

PANSS | Variable b | Paliperidone | Oral | Flexible | 10.8 | 104 | 58 (56) | 39.0 | NA | 51.0 | 101 | 63 (62) | 37.5 | NA | 53.4 |

| Pigott et al

Reference Pigott, Carson, Saha, Torbeyns, Stock and Ingenito26

(2003) |

PANSS | 26 | Aripiprazole | Oral | Fixed | 15 | 148 d | 84 (54.2) | 42.2 | NA | 81.2 | 149 d | 90 (58.1) | 41.7 | NA | 83.1 |

| Rui et al

Reference Rui, Wang, Liang, Liu, Wu and Wu27

(2014) |

PANSS | Variable b | Paliperidone | Oral | Fixed (3/6/9/12 mg/day) |

9.5 | 64 | 25 (39) | 31.1 | NA | 53.4 | 71 | 30 (42) | 32.3 | NA | 51.5 |

| Tandon et al

Reference Tandon, Cucchiaro, Phillips, Hernandez, Mao and Pikalov28

(2015) |

PANSS | 28 b | Lurasidone | Oral | Flexible | 78.9 | 143 d | 90 (62.5) | 43.0 | 17.8 | 53.2 | 141 d | 88 (62.4) | 42.4 | 16.5 | 54.5 |

PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; LAI, long-acting injection; NA, not available.

a. All studies were double masked. All studies included participants with a diagnosis of schizophrenia except Fu et al Reference Fu, Turkoz, Simonson, Walling, Schooler and Lindenmayer22 , which included patients with schizoaffective disorder only, and Beasley et al, Reference Beasley, Sutton, Hamilton, Walker, Dossenbach and Taylor19 which included both patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.

b. Terminated early.

c. Number of patients for whom PANSS or BPRS total scores were available.

d. PANSS or BPRS total scores were missing for at least one patient.

Results

Included studies

A total of 11 studies Reference Arato, O'Connor and Meltzer18–Reference Tandon, Cucchiaro, Phillips, Hernandez, Mao and Pikalov28 (n = 7 from the studies included in Leucht et al's meta-analysis; n = 4 from the additional literature search) involving 2826 participants (n = 1618 for antipsychotic treatment; n = 1208 for placebo treatment) that met eligibility criteria were identified and included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). The characteristics of these studies are summarised in Table 1, and stabilisation criteria for each are shown in online Table DS1. All studies were parallel-group RCTs conducted in a double-masked fashion with study duration ranging from 24 to 64 weeks. All patients included in the studies had schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and the majority of them had a chronic course of illness. All except one study examined SGAs; three studies included an LAI arm and two a low-dose antipsychotics arm; two studies used the BPRS, neither of which reported which item version of the BPRS was used; three studies included participants treated with LAI antipsychotics before randomisation; and, in three the studies' baseline standardised total score was >2. The results of risk of bias assessment are displayed in online Fig. DS1. Also, the sample sizes at each time point in the antipsychotic and placebo treatment groups are shown in online Tables DS2 and DS3, respectively.

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram of the literature search.

Symptom trajectories in antipsychotic versus placebo treatment

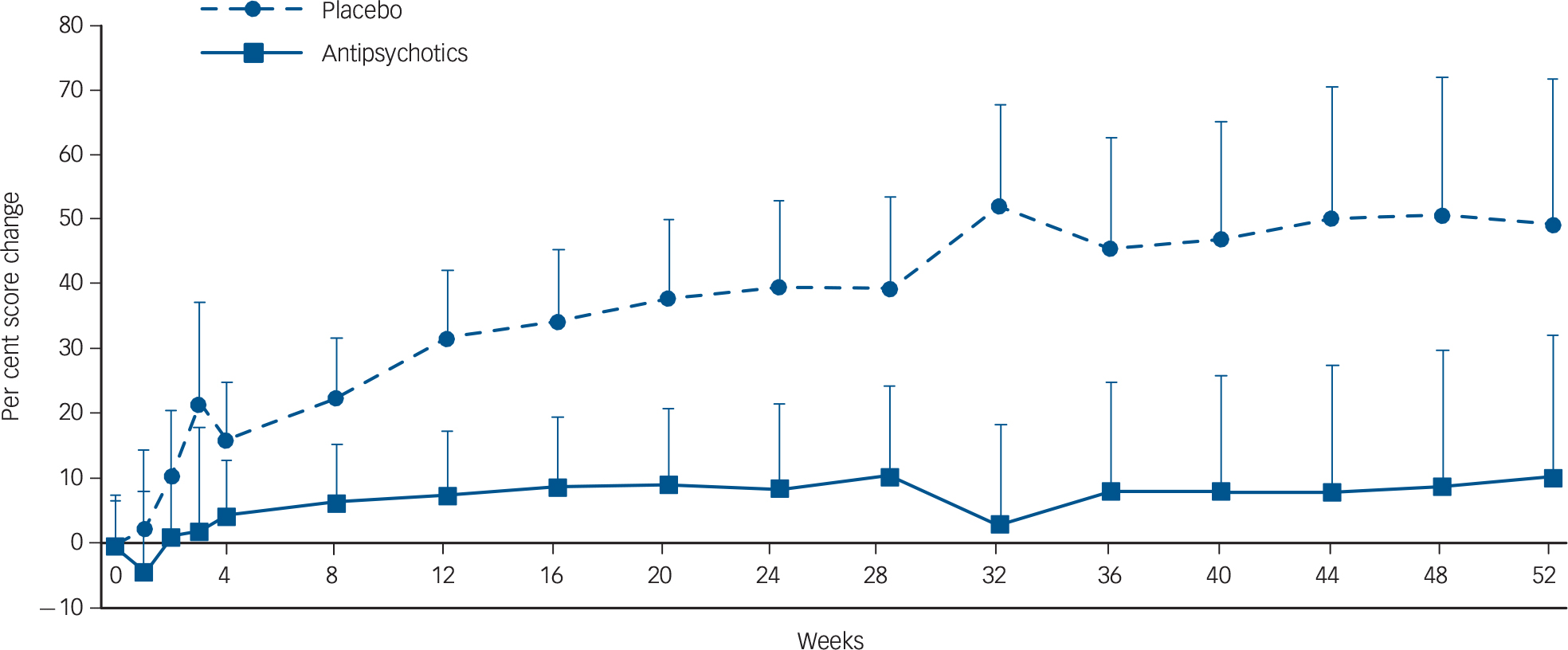

The symptom trajectories of standardised total scores and per cent score changes in the antipsychotic and placebo treatment arms are depicted in Figs 2 and 3, respectively. As indicated in Fig. 2, symptom severity remained nearly unchanged in patients continuing antipsychotic treatment, whereas symptom severity gradually and continuously worsened over time in those switching to placebo treatment; the interaction between group and time was statistically significant (F = 10.5, P<0.0001). Similarly, a placebo replacement was associated with a 49.2% worsening of symptoms from baseline to 52 weeks, in contrast to 10.1% in those who continued antipsychotic treatment; the interaction was significant (F = 8.34, P<0.0001) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2 Symptom trajectories indicated by standardised total score in patients with stable schizophrenia continuing antipsychotics (n=l6l8) versus switching to placebo (n=l208).

The mixed-model analysis revealed a significant interaction between group and time (F=10.5, P<0.0001). The y-axis indicates least squares means of standardised total scores.

Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals.

Fig. 3 Symptom trajectories indicated by per cent score change in patients with stable schizophrenia continuing antipsychotics (n=l6l8) versus switching to placebo (n=l208).

The mixed-model analysis revealed a significant interaction between group and time (F=8.34, P<0.0001). The y-axis indicates least squares means of per cent score changes.

Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals.

Sensitivity analyses revealed that the interactions between group and time remained statistically significant after excluding studies with use of BPRS (n = 2), LAI arms (n = 3), FGA arms (n = 2), low-dose antipsychotic arms (n = 2), placebo arms where participants were treated with LAI antipsychotics before randomisation (n = 3) or studies with a severe baseline symptom level (n = 3) (all Ps<0.0001).

Discussion

Main findings and comparison with findings from other studies

In patients with stable schizophrenia, we found that continuing antipsychotics significantly reduced symptom exacerbation over the following year when compared with individuals switched to placebo. Our findings corroborate the evidence from Leucht et al's meta-analysis showing that relapse risk in stable schizophrenia is reduced with antipsychotic maintenance treatment. Reference Leucht, Tardy, Komossa, Heres, Kissling and Salanti2 However, and most importantly, the current meta-analysis did not employ categorical outcomes that require a specific definition, such as relapse, exacerbation, remission and response, definitions that frequently vary between studies. Instead, we used total scores from the two most commonly employed rating scales in clinical trials involving schizophrenia. This allowed us to treat the data as a continuous variable and compare the trajectory of symptom changes between the two treatment groups with meta-regression analyses. Moreover, all included RCTs were conducted in a double-masked fashion and used placebo treatment rather than no treatment, even though these were not part of the eligibility criteria for the studies. This minimises the chance of performance biases, such as participant and assessor expectations, which can significantly influence results.

Our findings shed light on the importance of using symptom severity rather than relapse to evaluate long-term outcomes in schizophrenia; in contrast to Leucht et al's meta-analysis where the relapse rate between 7 and 12 months was as high as 27% even in patients continuing antipsychotic treatment, Reference Leucht, Tardy, Komossa, Heres, Kissling and Salanti2 our meta-analysis revealed no essential increment in symptom severity in those continuing antipsychotic treatment over 1 year. Further, the current meta-analysis demonstrated that the risk commences almost immediately and progresses in a linear fashion following antipsychotic discontinuation. From a clinical perspective, it argues for immediate and continuous monitoring; within the year following discontinuation there is no time point at which symptom exacerbation reaches a plateau. This said, it should be stressed that not all patient trajectories are the same. The mean score of overall symptom severity in patients receiving placebo can be affected by the scores in those who relapsed; in fact, a significant association between relapse rates and standardised symptom score changes was observed in patients undergoing placebo treatment (online Fig. DS2).

Considerations when interpreting our findings

It is worth highlighting once again that the majority of studies included in the current meta-analysis involved patients whose conditions were more chronic in nature; accordingly, the findings cannot be extrapolated to other populations such as those with first-episode schizophrenia. However, Leucht et al have indicated a greater relapse risk with placebo versus ongoing antipsychotic treatment in a subgroup of patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Reference Leucht, Tardy, Komossa, Heres, Kissling and Salanti2 In addition, Gitlin et al have demonstrated that the rate of symptom exacerbation continues to increase over 2 years in individuals with remitted recent-onset schizophrenia who discontinue treatment, Reference Gitlin, Nuechterlein, Subotnik, Ventura, Mintz and Fogelson29 which is also supported in a recent study and systematic review. Reference Zipursky, Menezes and Streiner30,Reference Mayoral-van Son, de la Foz, Martinez-Garcia, Moreno, Parrilla-Escobar and Valdizan31 Nonetheless, this does not rule out the following possibilities: (a) a specific group of patients may not require antipsychotic maintenance treatment following resolution of an acute psychotic episode; (b) antipsychotics can be reduced rather than totally discontinued. Naturalistic studies with a follow-up duration of 10 years or more have indicated that approximately one-third of patients with schizophrenia can remain stable in the absence of antipsychotic treatment. Reference Harrow, Jobe and Faull32–Reference Wils, Gotfredsen, Hjorth⊘j, Austin, Albert and Secher34 To date, though, no clinical factors have been definitively established that predict those individuals who will not experience relapse following antipsychotic discontinuation. Regarding the second issue, there is still ongoing debate as to whether antipsychotic dose reduction is feasible in terms of relapse prevention; Reference Takeuchi, Suzuki, Uchida, Watanabe and Mimura1 however, some studies have reported benefits with antipsychotic dose reduction, including improvement in motor and cognitive side-effects. Reference Inderbitzin, Lewine, Scheller-Gilkey, Swofford, Egan and Gloersen35,Reference Takeuchi, Suzuki, Remington, Bies, Abe and Graff-Guerrero36 Clinicians should continue to make efforts to minimise side-effects during the long-term antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia.

Given that the vast majority of included studies examined SGAs and a meta-analysis has shown that SGAs are superior to FGAs in terms of relapse prevention, Reference Kishimoto, Agarwal, Kishi, Leucht, Kane and Correll4 it remains unknown if FGAs demonstrate the same magnitude of separation over time versus placebo as SGAs. Another important issue is the type of antipsychotic formulation participants received prior to randomisation. Hypothetically, for patients treated with LAIs antipsychotic activity will persist for a longer interval owing to their prolonged plasma half-lives, which may alter symptom trajectories in the placebo treatment group even if participants received an abrupt switch to placebo. A previous meta-analysis showed that abrupt withdrawal of antipsychotics was related to a higher relapse rate compared with gradual discontinuation, Reference Viguera, Baldessarini, Hegarty, van Kammen and Tohen37 although Leucht et al's meta-analysis demonstrated no significant difference in relapse reduction between immediate and gradual antipsychotic discontinuation. Reference Leucht, Tardy, Komossa, Heres, Kissling and Salanti2 Indeed, all studies except one included in the current meta-analysis appeared to switch to placebo immediately; however, when limiting the analyses to studies where gradual antipsychotic discontinuation was adopted or participants had been treated with LAI antipsychotics before randomisation (n = 4), the findings remained unchanged (Ps>0.0001), suggesting that symptom severity may increase even if antipsychotic treatment is discontinued gradually.

Limitations

As expected, there was considerable variation between the studies included regarding criteria for both symptom and treatment stabilisation (see online Table DS1). This was reflected, for example, in differences in baseline symptom severity among studies; the majority of the studies had a PANSS total score in the range of 55, representing ‘borderline mentally ill’, Reference Leucht, Kane, Kissling, Hamann, Etschel and Engel38 although three studies had relatively severe symptomatology (Table 1). These three studies also included less stringent criteria for stabilisation and did not include a stabilisation phase where patients were treated with an antipsychotic for a defined period to confirm symptom and/or treatment stabilisation before treatment randomisation (online Table DS1). This was reflected in higher baseline scores but as part of our data analysis we controlled for baseline symptom severity and excluded the three studies for sensitivity analysis; however, results remained the same.

Since only one study had a follow-up period of longer than 1 year, we could not examine the time course of symptoms beyond 52 weeks. This underscores the paucity of longer-term RCTs comparing clinical outcomes between antipsychotics and placebo, although there are ethical concerns related to prolonged placebo exposure. Among the 11 studies included, three adopted a variable duration design and six were terminated early as they involved trials of new antipsychotics where efficacy was established in the course of interim analyses. Long-term antipsychotic exposure may be associated with unfavourable consequences, including structural brain changes and dopamine receptor supersensitivity (see the recent argument on long-term prophylactic use of antipsychotics Reference Murray, Quattrone, Natesan, van Os, Nordentoft and Howes39 ). Moreover, Wunderink et al have reported that patients with remitted first-episode psychosis (approximately 70% with a diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorders) receiving antipsychotic reduction/discontinuation are more likely to achieve functional remission over 7 years compared with those continuing antipsychotic treatment Reference Wunderink, Nieboer, Wiersma, Sytema and Nienhuis40 despite shorter-term clinical outcomes being worse. Reference Wunderink, Nienhuis, Sytema, Slooff, Knegtering and Wiersma41 Thus, our findings cannot speak to what might occur beyond 1 year, nor do they address other measures such as functional outcome. Given that functional outcome is important in discussions of recovery in patients with schizophrenia, Reference Jaaskelainen, Juola, Hirvonen, McGrath, Saha and Isohanni42 clinicians must balance symptomatic and functional outcomes.

Other limitations need to be noted as well. First, the number of included studies is relatively small compared with the meta-analysis of Leucht et al (n = 11 v. 65); whereas that meta-analysis involved approximately 6500 participants, ours included 2826. Second, six studies reported only baseline and end-point data, which resulted in fluctuations in sample sizes across time (online Tables DS2 and DS3). Third, we only included studies using a LOCF method because of our intention to add sample weights in the meta-regression analyses. An additional reason behind this strategy was the fact that most studies did not report sample size at each time point for PANSS or BPRS total scores. Thus, we excluded five studies that used either an observed case analysis (n = 1) or did not report which approach they adopted (n = 4) (Fig. 1). This inclusion criterion may limit the generalisability of our findings, although a previous meta-analysis examining the time course of symptom improvement in antipsychotic treatment demonstrated no difference in rates of score changes over time between the two methods. Reference Agid, Kapur, Arenovich and Zipursky8 Fourth, among five studies reporting PANSS subscale scores (four studies had solely baseline and end-point data, and one study had a third time point), only two studies shared the same time points other than baseline, which prevented us from examining trajectories of different symptom domains such as positive and negative symptoms. Finally, our findings cannot be applied to clozapine, the sole antipsychotic medication approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, based on evidence that its time course of symptom improvement differs from other antipsychotics. Reference Suzuki, Remington, Arenovich, Uchida, Agid and Graff-Guerrero10,Reference Sherwood, Thornton and Honer11

Implications

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis indicates that patients with stable schizophrenia who continue antipsychotic treatment demonstrate ongoing symptom stabilisation over a 1-year interval, in contrast to a trajectory of continuous symptom exacerbation observed in patients receiving placebo. This highlights the clinical benefits of antipsychotic maintenance treatment, at least in chronic schizophrenia, as well as the necessity of immediate and ongoing monitoring for clinical worsening in the face of antipsychotic discontinuation. However, given that the current meta-analysis does not address symptomatic outcome beyond 1 year, or functional outcome, clinicians should make decisions on the long-term antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia based on individual patient needs. It has been suggested that there is a subgroup of individuals who do not require ongoing antipsychotic treatment, Reference Harrow, Jobe and Faull32,Reference Harrow and Jobe43 but who these individuals are or when it is safe to discontinue maintenance treatment in those that remain stabilised, represent unanswered questions.

Funding

H.T. is supported through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) fellowship programme. This funding source had no rote in study design, statistical analsis or interpretation of findings, or in manuscript preparation or submission for publication. H.T. has received fellowship grants from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) Foundation, the Japanese Society of Clinical Neuropsychopharmacology and the Astellas Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms Sadhana Thiyanavadivel for her kind help.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.