Abnormalities in the lateral prefrontal cortex have been the focus of schizophrenia research for many years. Increased and decreased activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, predominantly in the context of working memory tasks, has been discussed extensively. Reference Manoach1 Recently, however, evidence is increasing that alterations in medial frontal areas that have been largely disregarded during the past decade of schizophrenia research deserve closer inspection. Thus, processes known to critically depend on medial prefrontal cortex areas, like for example performance monitoring Reference van Veen and Carter2 or judging mental states of the self and others, Reference Bora, Yucel and Pantelis3 have been found to be impaired in the context of the disorder and to go along with altered activation in mainly medial frontal areas. Reference van Veen and Carter2,Reference Lee, Brown, Egleston, Green, Farrow and Hunter4 Moreover, individuals with schizophrenia have been found to exhibit altered activation in medial frontal networks also in association with tasks that are not primarily linked to medial frontal cortex areas. Reference Koch, Wagner, Nenadic, Schachtzabel, Schultz and Roebel5,Reference Schlagenhauf, Dinges, Beck, Wustenberg, Friedel and Dembler6

Given the increasing evidence for altered neural activation in schizophrenia in both medial and lateral frontal areas the question arises whether there is a link to structural abnormalities that are frequently being discovered when comparing people with schizophrenia with healthy volunteers, particularly in white matter fibre tracts connecting frontal and temporal regions. Reference Kyriakopoulos, Bargiotas, Barker and Frangou7 Interestingly, a recent multimodal imaging study identified the medial prefrontal cortex (mainly Brodmann's areas 6/8) as a central region of abnormality that exhibited both structural and functional changes in a sample of people with chronic schizophrenia. Reference Pomarol-Clotet, Canales-Rodriguez, Salvador, Sarro, Gomar and Vila8 Here, structural changes were detectable in the form of grey matter reductions and alterations in white matter. Over 20 studies have indicated white matter alterations in schizophrenia. Reference Kyriakopoulos, Bargiotas, Barker and Frangou7 However, most of these studies investigated fractional anisotropy – a parameter derived from a combination of estimates of axial diffusivity (i.e. diffusivity parallel to the axon) and radial diffusivity (i.e. diffusivity perpendicular to the axon). Axonal damage, such as that caused by a stroke, results in a significant decrease in axial diffusivity as has been shown in experiments with shiverer mice in vivo. Reference Song, Sun, Ju, Lin, Cross and Neufeld9 In contrast, dysmyelination of axons has been shown to be associated with an increase in radial diffusivity without changing axial diffusivity. Reference Song, Sun, Ramsbottom, Chang, Russell and Cross10 Hence, it is surprising that, although dysmyelination is being discussed as a central pathophysiological process in schizophrenia, potential alterations in radial diffusivity have barely been investigated.

Therefore the present study's aim was to investigate potential activation abnormalities in predominantly medial frontal areas in individuals with schizophrenia and relate them to potential alterations in radial diffusivity. Multiple studies in healthy volunteers have demonstrated that tasks that require decisions under uncertainty or processing of ambiguous or uncertain information evoke strong activation in frontomedial areas. Reference Goel and Dolan11–Reference Volz, Schubotz and von Cramon13 Thus, we asked a sample of people with chronic, subacute schizophrenia to perform a task where the condition of interest demanded decision-making under maximum uncertainty. The study is an extension to the findings of a recent study which showed that participants with schizophrenia exhibited increased activation in a frontocingulate network despite increasing predictability (i.e. decreasing uncertainty) when compared with healthy volunteers. Reference Koch, Schachtzabel, Wagner, Schikora, Schultz and Reichenbach14 Linked to this relative activation increase was a significantly impaired ability in these individuals to learn stimulus–consequence contingencies on the basis of feedback and reward. In the present study, we investigated decision-making under conditions of maximum uncertainty that allowed no learning. This has the advantage that results are not confounded by the effects of performance differences – an influencing factor that has been shown to be of major relevance when comparing neural activation between participants with schizophrenia and healthy volunteers. Reference Van Snellenberg, Torres and Thornton15 We expected structural alterations in relevant white matter fibre tracts in those with schizophrenia to go along with altered connectivity and, maybe even as a direct consequence, alterations in absolute intensity of neural activation within associated networks. We expected they would show altered activation in mainly medial frontal regions in association with decision-making under maximum uncertainty. We anticipated these activation changes to be linked to an increased radial diffusivity in relevant fibre tracts.

Method

Participants

The study included 19 right-handed Reference Annett16 people with chronic schizophrenia (the schizophrenia group: 12 males, 7 females; diagnosed by DSM–IV 17 ) and 20 right-handed healthy people (the control group: 12 males, 8 females). On average, the individuals in the schizophrenia group were 35.2 (s.d. = 11.5) years old and had a mean education of 10.58 (s.d. = 2.06) years. For the control group the mean age was 29.7 (s.d. = 9.1) and mean education 12.70 (s.d. = 0.92) years. There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of age (t(37) = 1.62, n.s.) but a significant difference regarding education (t(37) = –4.12, P<0.01, corrected for unequal variances). Diagnosis was established by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders (SCID–I) Reference First, Spitzer, Williams and Gibbon18 and confirmed by two independent clinical psychiatrists (R.S. and Ch.S.). Participants in the schizophrenia group were free of any concurrent psychiatric diagnosis and had no neurological conditions. They were in remission from an acute psychotic episode and, apart from one person who was unmedicated, on stable medication with atypical antipsychotics. The psychopathological status of the schizophrenia group was assessed by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler19 Ratings were 15.4 (s.d. = 4.7) on the positive subscale, 18.8 (s.d. = 6.8) on the negative subscale, and 35.8 (s.d. = 7.6) on the general psychopathology scale. A verbal multiple choice IQ test Reference Lehrl20 confirmed that none of the participants had an intellectual disability (IQ<80).

The control group were screened using comprehensive assessment procedures for medical, neurological and psychiatric history. Exclusion criteria were current and potentially interfering medical conditions, any current or previous neurological or psychiatric disorder, and first-degree relatives with Axis I psychiatric or neurological disorders. All participants gave written informed consent to a study protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of the Friedrich-Schiller-University Medical School.

Experiment design

Using the Presentation software package version 14.6 (Neurobehavioral Systems Inc, USA; www.neurobs.com) for Windows, stimuli were projected onto a transparent screen inside the scanner tunnel that could be viewed by the participant through a mirror system mounted on top of the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) head coil. The participant's responses were recorded by using an MRI-compatible fibre optic response device (Lumitouch, Photon Control Inc, Burnaby, Canada) with four button keypads for the right hand.

A probabilistic trial-and-error learning task arranged as an event-related design was applied. This task is similar to a task used previously in healthy controls. Reference Koch, Schachtzabel, Wagner, Reichenbach, Sauer and Schlösser21 For the purpose of patient studies, however, task difficulty had been reduced. In this task participants were presented with a card with a geometrical figure on it (i.e. circle, cross, half-moon, triangle, square or pentagon). They were told that each figure was associated with an unknown value ranging from 1 to 9. Participants were asked to guess whether the figure on the card predicted a value higher or lower than the number five and were told that each correct guess was followed by a monetary reward (+ e0.50) whereas each wrong guess was followed by a punishment (–e0.50). Participants were also instructed that each figure predicted the respective value (higher or lower than five) with a certain probability. Three conditions were employed: one highly uncertain condition that did not allow any outcome prediction (i.e. 50% stimulus–outcome contingency), one condition permitting full prediction (i.e. 100% stimulus–outcome contingency) and one condition where prediction was partly possible (i.e. 81% stimulus–outcome contingency). Participants were not informed about the predictive probabilities of the respective figures. Thus, they had to learn to improve their guesses based on the different prediction probabilities in the course of the experiment in order to maximise their gains. The whole paradigm consisted of a series of 96 interleaved trials with 16 trials for each probability condition. Each trial started with the presentation of the probability condition-specific figure, which was shown for 1.5 s. After an inter-stimulus interval lasting 4.5 s a question mark was presented for 2.5 s during which participants had to answer by button press. After another inter-stimulus interval of 4.5 s the correct solution followed by the indication of a reward or punishment appeared for 2.5 s. Each trial ended with an inter-trial interval lasting 3.5 s. In addition, we introduced a temporal jitter by varying the second inter-stimulus interval between 4.5 and 5.5 s in order to increase sensitivity. The inter-stimulus interval served as an implicit baseline. Participants were compensated according to their performance, although the minimum of e20 was guaranteed for volunteering.

Functional MRI (fMRI) procedure

Functional data were collected on a 3 T Siemens TIM Trio whole body system (Magnetom TIM Trio, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a 12-element receive-only head matrix coil. Foam pads were used for positioning and immobilisation of the participant's head within the head coil. T * 2-weighted images were obtained using a gradient-echo EPI sequence (repetition time (TR) = 2040 ms, echo time (TE) = 26 ms, flip angle 90°) with 40 contiguous transverse slices of 3.3 mm thickness covering the entire brain. The matrix size was 72×72 pixels with an in-plane resolution of 2.67×2.67 mm2 corresponding to a field of view (FOV) of 192×192 mm. A series of 965 whole-brain volume sets were acquired, with the first three images of each series being discarded.

High-resolution anatomical T 1-weighted volume scans (magnetisation prepared rapid gradient echo, MP-RAGE) were obtained in sagittal orientation (TR = 2300 ms, TE = 3.03 ms, TI = 900 ms, flip angle, 9°, FOV = 256 mm, matrix 256×256 mm, number of sagittal slices 192, acceleration factor (parallel acquisition techniques, PAT) = 2, acquisition time (TA) = 5 min 21 s) with a slice thickness of 1 mm and isotropic resolution of 1×1×1mm3.

Diffusion tensor imaging procedure

Diffusion data were collected with the same coil on the same scanner. Diffusion-weighted images were obtained using echoplanar imaging (TR = 8000 ms, TE = 83 ms, FOV = 256 mm, with an in-plane resolution of 2 mm, a slice thickness of 2 mm, number of slices 71, an iPAT factor of 3, and a phase partial fourier of 6/8). Diffusion-sensitising gradient encoding was applied in 30 different directions with a diffusion-weighing factor of b = 1000 s/mm2 and one b 0 (b = 0) image. Images were acquired parallel to the anterior–posterior commissure.

Data analysis

Behavioural data

Performance was assessed by the percentage of correct reactions. A one-way ANOVA with group (schizophrenia group, control group) as between-participant factor was performed to test for performance differences.

fMRI data

Preprocessing and statistical analysis of the fMRI data was performed using SPM5 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London; www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) for Windows. Functional data were corrected for differences in time of acquisition by sinc interpolation, realigned to the first image of each session and linearly and non-linearly normalised to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI, Montreal, Canada) reference brain (MNI–152 average brain). Data were spatially smoothed with a Gaussian kernel (8 mm, full-width at half-maximum) and high-pass filtered with a 128 s cut-off. All data were inspected for movement artefacts. Participants with movement parameters exceeding 3 mm translation on the x-, y-, or z-axis or 3° rotation were excluded. In addition, individual movement parameters entered analyses as covariates of no interest.

Brain activations were then analysed voxel-wise to calculate statistical parametric maps of t-statistics for each condition of the task described above: stimulus encoding, 50% probability condition (i.e. activation during responding to triangles and pentagons), 81% probability condition (i.e. activation during responding to circles and squares), 100% probability condition (i.e. activation during responding to half-moons and crosses) and feedback (positive or negative feedback) condition (i.e. activation during presentation of correct or incorrect solution and indication of monetary win or loss modelled by separate regressors). Blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal changes for the different conditions were modelled as a covariate of variable length boxcar functions and convolved with a canonical haemodynamic response function. These haemodynamic response functions were then used as individual regressors within the general linear model. A fixed-effect model at the single-participant level was performed to create images of parameter estimates. A one-way ANOVA with group (schizophrenia group, control group) as the between-participant factor was performed on the second level to test for group differences in activation in association with decision-making under maximum uncertainty (i.e. activation in association with a 50% probability condition v. implicit baseline activation). Results were based on a false discovery rate corrected significance threshold of P<0.01. Number of expected voxels per cluster was taken as a spatial extent threshold. Coordinates were transformed into Talairach coordinates using the algorithm proposed by Brett et al. Reference Brett, Johnsrude and Owen22

Diffusion tensor imaging data

The diffusion-weighted images were registered to the non-diffusion weighted b 0 image by affine transformations to minimise distortions because of eddy currents and to reduce simple head motion using eddy current correction as implemented in FSL (FMRIB Software Library, FMRIB, Oxford, UK, http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/). In order to remove non-brain tissue components and background noise, images were extracted using Brain Extraction Tool (BET), also compiled in FSL. Reference Smith, Jenkinson, Woolrich, Beckmann, Behrens and Johansen-Berg23 Next, a diffusion tensor model was fitted in each voxel to provide a voxel-wise analysis of diffusion image maps with axial diffusivity constituting the first eigen vector of the tensor model and radial diffusivity obtained by calculating the mean of the second and third eigen vector, i.e. (λ2 + λ3)/2. Using SPM5 each individual diffusivity map was then coregistered to the individual high-resolution anatomical volume. Each individual high-resolution anatomical volume was linearly and non-linearly normalised to the Montreal Neurological Institute template (MNI–152 average brain) provided by SPM.

The estimated normalisation parameters were then applied to the coregistered diffusion tensor imaging maps and spatially smoothed. A kernel size of 4 times the voxel size has been demonstrated to be most appropriate for detecting white matter differences between individuals with schizophrenia and controls. Reference Jones, Symms, Cercignani and Howard24 As the diffusion tensor tends to be highly variable predominantly perpendicular to the axon Reference Moraschi, Hagberg, Di Paola, Spalletta, Maraviglia and Giove25 smoothing with a large kernel size may cause a loss of directional and structural information. We therefore chose a smoothing kernel size of 8 mm (Gaussian kernel, full-width at half-maximum).

Images were manually inspected for artefacts. Data from one healthy volunteer had to be excluded from analyses. A one-way ANOVA with group (schizophrenia group, control group) as between-participant factor was performed on the second-level testing for altered radial diffusivity in individuals in the schizophrenia group across the entire volume. To investigate a potential effect of atypical antipsychotic medication on radial diffusivity, medication was converted to chlorpromazine equivalent dosage Reference Atkins, Burgess, Bottomley and Riccio26,Reference Mori, van Zijl, Wakana and Nagae-Poetscher27 and correlated with radial diffusivity extracted from the cluster that turned out to be altered in radial diffusivity in individuals with schizophrenia. To investigate potential age effects on radial diffusivity age was likewise correlated with radial diffusivity extracted from this cluster.

To post hoc investigate whether diffusivity in the cluster that showed the greatest alteration in radial diffusivity in the individuals in the schizophrenia group was also altered in an axial direction another one-way ANOVA testing for altered axial diffusivity was performed with group (schizophrenia group, control group) as the between-participant factor and the extent of the cluster showing alterations in radial diffusivity as the spatial extent threshold.

Finally, a potential relationship between altered radial diffusivity and neural activation was investigated. Minimum radial diffusivity from the cluster that showed alteration in radial diffusivity in individuals with schizophrenia compared with controls was extracted from the diffusivity map of each participant in the schizophrenia group and correlated with neural activation across the entire volume. The Matlab (www.mathworks.com) image processing toolbox and in-house software were used for data extraction. Analyses of potential group differences in diffusivity were based on a false discovery rate corrected threshold of P<0.05. Correlation between diffusivity and neural activation was based on a threshold of P<0.001 uncorrected with number of expected voxels as a spatial extent threshold.

Results

Behavioural data

The one-way ANOVA on the percentage of correct responses in association with decision-making under maximum uncertainty yielded no significant group effect (F(1,37) = 1.0), indicating that groups did not differ in performance under conditions of maximum uncertainty (for more detailed results please refer to Koch et al). Reference Koch, Schachtzabel, Wagner, Schikora, Schultz and Reichenbach14

Diffusion tensor imaging data

The one-way ANOVA showed a significantly increased radial diffusivity (Fig. 1) in the schizophrenia group compared with the controls in a cluster comprising white matter of the left superior temporal gyrus most probably containing fibres from the inferior longitudinal fasciculus as well as short-ranging association fibres (x = –61, y = –25, z =5, T = 6.38, k = 20). Reference Ridderinkhof, Ullsperger, Crone and Nieuwenhuis28 The correlation between the radial diffusivity values extracted from this cluster and antipsychotic dosage (in terms of chlorpromazine equivalents) was not significant (r = –0.24); the same applied for the correlation with age (r = 0.05). The one-way ANOVA investigating differences in axial diffusivity between the groups yielded likewise a significantly increased axial diffusivity in the schizophrenia group compared with the control group in white matter of the left superior temporal gyrus (x = –61, y = –21, z =5, T = 7.08, k = 105, x = –44, y = –17, z =5, T = 6.27, k = 47). In addition, there was an increased axial diffusivity in the schizophrenia group compared with the control group in a white matter cluster adjacent to the middle temporal gyrus (x = – 52, y = –43, z = –11, T = 5.17, k = 22).

Fig. 1 Individual and mean (s.d.) radial diffusivity in participants in the control group and schizophrenia group extracted from superior temporal lobe white matter, showing significantly increased diffusivity in those with schizophrenia compared with controls.

fMRI data

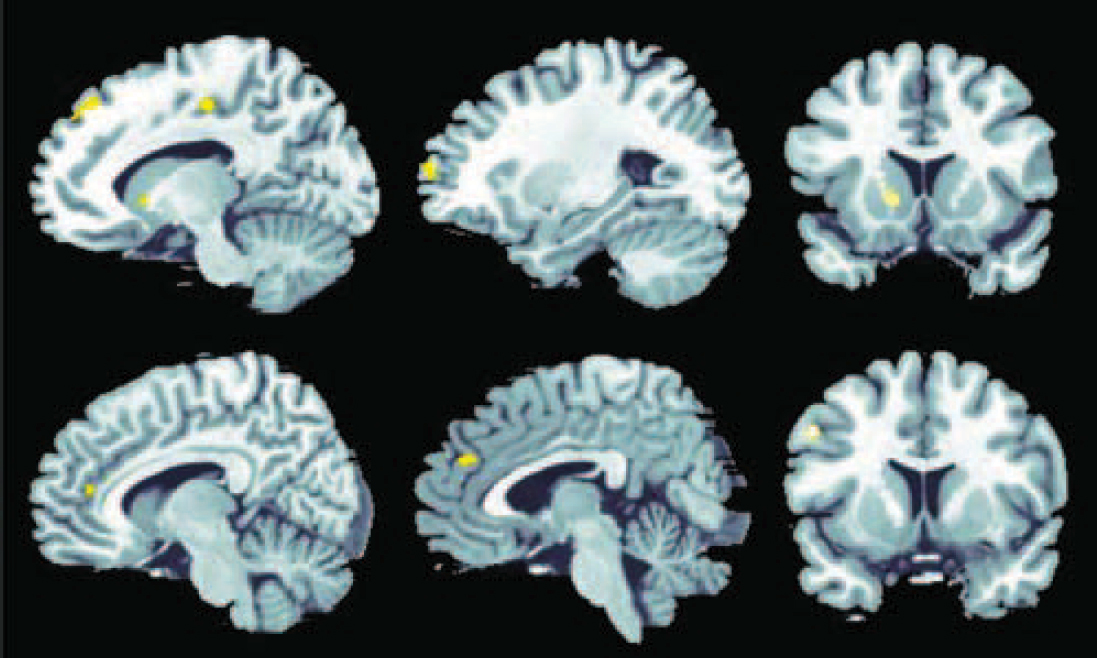

Analysis of activation in association with decision-making under maximum uncertainty yielded significant activation in the control group in an extended network containing mainly frontal, parietal and occipital regions (Fig. 2(a)). In the schizophrenia group, activation was restricted predominantly to the occipital cortex (Fig. 2(b)).

Fig. 2 Significant activation in individuals in the control group (a) and the schizophrenia group (b) in association with decision-making under uncertainty at P<0.01, false discovery rate corrected.

The group comparison yielded significantly decreased activation in the schizophrenia group compared with the control group in a predominantly right-lateralised network containing inferior and superior frontal areas, the anterior cingulate and putamen (Table 1 andFig. 3). The opposite contrast yielded no significant results.

Table 1 Areas showing decreased activation in the schizophrenia group compared with the control group in association with decision-making under maximum uncertainty

| Talairach coordinate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region of activation | Side | x | y | z | T | k |

| Superior frontal gyrus, Brodmann's area 10 | Right | 26 | 62 | 8 | 5.94 | 61 |

| Medial frontal gyrus, Brodmann's area 8 | Right | 4 | 50 | 26 | 5.89 | 99 |

| Superior frontal gyrus, Brodmann's area 8 | Right | 12 | 48 | 42 | 5.83 | 126 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus, Brodmann's area 9 | Right | 50 | 9 | 33 | 5.54 | 13 |

| Anterior cingulate, Brodmann's area 24 | Right | 14 | – 17 | 43 | 5.51 | 24 |

| Anterior cingulate, Brodmann's area 32 | Left | – 8 | 39 | 9 | 5.26 | 10 |

| Middle frontal gyrus, Brodmann's area 9 | Right | 32 | 32 | 21 | 5.14 | 11 |

| Putamen | Right | 12 | 14 | – 3 | 4.96 | 10 |

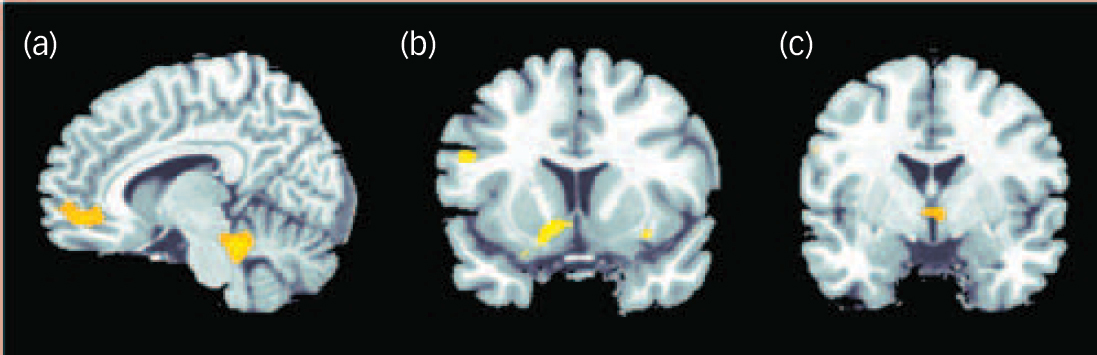

The positive correlation between degree of radial diffusivity extracted from the temporal cluster showing an increased diffusivity in the schizophrenia group and neural activation in association with decision-making under maximum uncertainty revealed no significant results. The negative correlation yielded significant results in a network containing inferior frontal and cerebellar areas, the anterior cingulate, putamen, insula and hypothalamus (Table 2 andFig. 4).

Table 2 Areas showing decreased activation in association with increased temporal lobe diffusivity in the schizophrenia group

| Talairach coordinate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region of activation | Side | x | y | z | T | k |

| Cerebellum | Left | – 8 | – 36 | – 18 | 7.08 | 161 |

| Cerebellum | Right | 26 | – 52 | – 31 | 5.34 | 91 |

| Anterior cingulate, Brodmann's area 32/24 | Right | 12 | 36 | – 12 | 5.57 | 89 |

| Anterior cingulate, Brodmann's area 32/24 | Left | – 10 | 37 | – 9 | 5.23 | 121 |

| Insula, Brodmann's area 22 | Right | 46 | – 28 | – 5 | 4.61 | 26 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | Right | 36 | 25 | – 13 | 4.22 | 16 |

| Putamen | Right | 16 | 9 | – 11 | 4.10 | 25 |

| Hypothalamus | Left | – 4 | – 2 | – 4 | 4.07 | 15 |

Discussion

Main findings

The present study investigated the relationship between altered diffusivity and neural activation in people with schizophrenia. The schizophrenia group showed a significantly decreased activation in a frontostriatocingulate network in association with decision-making under uncertainty. The direct correlation between the degree of radial diffusivity and functional activation yielded a negative relation between diffusivity and activation in several task-relevant regions, indicating that structural alterations may be closely related to the observed activation deficits.

Fig. 3 Significantly stronger activation in the participants in the control group compared with the schizophrenia group in association with decision-making under uncertainty at P<0.01, false discovery rate corrected.

Significant effects were detectable in the frontal cortex (Brodmann's area 8/9/10), anterior cingulate cortex (Brodmann's area 24/32) and putamen.

On the performance level, the schizophrenia group did not significantly differ from the control group. This finding is according to expectation as learning was not possible under the task condition of interest, which was characterised by maximum uncertainty or, in other terms, lacking predictability regarding stimulus contingencies.

Alterations in neural activation

Despite comparable performance, there was a significantly decreased activation in the schizophrenia group compared with the control group in a frontocingulostriatal network. As expected, besides the dorsal striatum, medial frontal regions were strongly affected. Both lateral and medial prefrontal as well as anterior cingulate areas are known to be critically involved in processes demanding a high amount of cognitive control, like for example decision-making under uncertainty. Reference Heckers, Weiss, Deckersbach, Goff, Morecraft and Bush29 Likewise, the medial prefrontal cortex has repeatedly been found to play a relevant role in processing of uncertain information. Reference Heckers, Weiss, Deckersbach, Goff, Morecraft and Bush29 Evidence on altered activation in schizophrenia in the context of learning or decision-making under uncertainty is scarce. The findings are, however, in line with several previous studies that revealed decreased activation in schizophrenia in a frontocingulate network in association with uncertain or, at least, highly demanding task conditions. Reference Koch, Schachtzabel, Wagner, Schikora, Schultz and Reichenbach14,Reference Woods30,Reference Weiss, Siedentopf, Golaszewski, Mottaghy, Hofer and Kremser31 It should be noted, however, that predominantly in the context of high task demands, it cannot be excluded that activation differences mainly reflect the participants’ reduced efforts to cope with the task. But even then the decreased activation in these individuals could be regarded in light of a diminished cognitive control in association with the processing of uncertain information.

Fig. 4 Negative correlation between degree of radial diffusivity extracted from the temporal lobe cluster showing a difference in diffusivity between the groups and neural activation in association with decision-making under uncertainty in the schizophrenia group.

Significant effects at P<0.001 uncorrected were detectable in the cerebellum and anterior cingulate cortex (a), insula and putamen (b) and hypothalamus (c).

Alterations in diffusivity

Apart from the functional alterations, we found significant structural changes in terms of an increased radial and axial diffusivity in the schizophrenia group compared with the control group in the white matter of the superior temporal gyrus presumably containing mainly short-ranging association fibres as well as fibres from the inferior longitudinal fasciculus.

Given the study by Song et al Reference Song, Yoshino, Le, Lin, Sun and Cross32 demonstrating that increased radial diffusivity constitutes a marker of dysmyelination whereas axonal damage, for example caused by a stroke, results in a significant decrease in axial diffusivity, these present findings may indicate impaired axonal integrity as well as alterations in myelination as structural substrates of this altered diffusivity. Recent results from a study with simulated and in vivo data, Reference Wheeler-Kingshott and Cercignani33 however, demonstrate that a simplistic biological interpretation of radial and axial diffusivity output should be avoided as inter-individual variation in underlying tissue architecture can be extensive and interactions between anatomical and scanning parameters can also produce abnormally high and low diffusivity values. Further studies are needed to determine whether increased radial or axial diffusivity can really be regarded as indicators of alterations in myelination or axonal architecture linked to the disorder.

Alterations in radial diffusivity have barely been investigated before in people with schizophrenia. Seal et al examined directionality of diffusion in addition to fractional anisotropy and found an increased radial diffusivity in the capsula externa in people with schizophrenia compared with healthy volunteers. Reference Seal, Yucel, Fornito, Wood, Harrison and Walterfang34 One can only speculate on the reasons for the differences between our findings and those of Seal and colleagues. It is highly probable that the different analysis methods were the decisive factor as Seal et al used a tract-based analysis method that includes only major fibre tracts.

Several studies reported white matter density reductions in left temporal white matter. Reference McDonald, Bullmore, Sham, Chitnis, Suckling and MacCabe35–Reference Whitford, Grieve, Farrow, Gomes, Brennan and Harris37 Accordingly, a recent meta-analysis by Ellison-Wright et al looking for consistent regional white matter changes in schizophrenia found significant reductions in two regions – the left frontal white matter and the left temporal white matter. Reference Ellison-Wright and Bullmore38 Although the temporal white matter cluster that this meta-analysis identified as most consistently reported across all studies was located somewhat more laterally than the temporal white matter cluster in the present study, evidence that the temporal lobe is predominantly affected by structural alterations in people with schizophrenia is increasing.

Link between neural activation and diffusivity

In the present study, the correlation between diffusivity and neural activation showed the increased radial diffusivity in the temporal cluster (presumably containing mainly short-ranging association fibres as well as fibres from the inferior longitudinal fasciculus) to be negatively correlated with activation in cingulate and lateral frontal regions, the dorsal striatum, the hypothalamus, left and right cerebellum and the right insula. This negative association indicates that in the schizophrenia group more distinct white matter deficits are linked to relatively weaker activation during decision-making under maximum uncertainty. To check the specificity of this association we ran another two control analyses correlating radial diffusivity of two frontal clusters (medial frontal lobe at x = –4, y = 15, z = 34; superior frontal lobe at x = 18, y = 33, z = 37) with activation and found no significant effects at P<0.001 uncorrected. These null effects emphasise the relevance of the association between diffusivity and activation detected for the superior temporal cluster and speak against a more general effect of individual differences in whole-brain white matter integrity correlation with brain activation.

Thus, present data suggest that deficits in white matter fibre tracts may constitute the structural basis of alterations in cerebral activation. Although speculative, these deficits in activation might reflect an impaired functional coupling between relevant areas within this network that may constitute the consequence of deficits in anatomical connections because of deficient association fibres. Reference Stephan, Baldeweg and Friston39

As illustrated by the direct group comparison the schizophrenia group as a whole exhibited significantly weaker activation compared with the control group in parts of this network in association with decision-making under uncertainty. As discussed above, lateral frontal and dorsal cingulate areas are known to play a central role in processing of uncertain information and have been found to display relative activation decreases in this context in people with schizophrenia. In a previous study, we likewise found insula and putamen to show a significantly decreased activation in association with decision-making under uncertainty and processing of feedback and reward. Reference Koch, Schachtzabel, Wagner, Schikora, Schultz and Reichenbach14

Closely linked to the processing of uncertainty is the expectation of a negative feedback or unpleasant consequence (like for example in the present study a monetary loss). A recent study by Herwig et al Reference Herwig, Abler, Walter and Erk40 investigated the neural correlates of the expectation of unpleasant stimuli and found activation in a network comprising mainly cingulate cortex, prefrontal areas, hypothalamus, striatum and insula – regions that were underactivated in people with schizophrenia in association with the processing of uncertainty in our study. Along the same lines, Singer et al Reference Singer, Critchley and Preuschoff41 proposed that the insula is involved in learning about risk and uncertainty associated with a given decision and integrates this information with representations of bodily and affective states in accordance with the individual's risk preference and appraisal of the context. Hence, the decreased activation in the schizophrenia group in association with decision-making under uncertainty may reflect a decreased affective reactivity to uncertainty (and its associated negative consequences) that is closely linked to the psychopathology of the disorder and seems to be mediated by structural alterations in white matter.

Although, as discussed above, an association between alterations in diffusivity and deficits in myelination should be established with caution, considering that myelin not only serves the electrical isolation of axons but is also relevant for axonal signal propagation, it is conceivable that disturbed myelination results in a disturbed functional interplay and – maybe even consequently – weaker activation within relevant parts of this network.

Furthermore, there is evidence for an inverse association. A study examining the thickness of myelin sheath in mice has demonstrated that reduced neuronal activity in grey matter contributes to loss of myelination in white matter by showing that the thickness of myelin sheaths in axons depended on the degree of nerve signalling. Reference Michailov, Sereda, Brinkmann, Fischer, Haug and Birchmeier42 Studies on deafferented individuals reporting grey matter decreases as a consequence of lacking afferent input following limb amputation Reference Draganski, Moser, Lummel, Ganssbauer, Bogdahn and Haas43 point in a similar direction and give reason to assume that reduced activation in certain brain areas might also be linked to reduced axonal function. These conclusions have, however, to be drawn with caution and further studies using multimodal imaging are needed to clarify the precise nature of this apparent link between structural alterations and neural activity.

Funding

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [KO ])

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.