There has been a shift in the field regarding how to assess and classify personality disorders. Problems with the categorical system of personality disorder diagnosis have been widely documented.Reference Samuel, Griffin and Huprich1 These include the instability of many personality disorder categories, the arbitrary use of cut-off scores to assign a personality disorder diagnosis and the difficulty of identifying personality disorders as distinct, non-overlapping diagnostic categories. Thus, it has been suggested that trait theory offers the best hope for informing a scientific classification system.Reference Clark, Watson and Reynolds2–Reference Widiger, Simonsen, Krueger, Livesley and Verheul7 Personality traits are described as being hierarchically organised and deconstructed into their component facets. Reviews of the most common trait classification system, the five-factor model,Reference Costa and Widiger5 found that patients with a DSM-based personality disorder have a trait profile consistent with what would be expected, but also have elevated or suppressed scores on a number of other trait dimensions, thus calling into question whether a clear map exists between the DSM personality disorders and their profile.Reference Samuel and Widiger8 Many have suggested that the categories are not as useful as a trait framework because of its capacity to assess many characteristics in personalities not represented in the extant DSM categories.

Because of these findings, section III of the DSM-59 and the upcoming ICD-11 allow for the assessment of the individual's traits, which are assessed with the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 (PID-5Reference Krueger, Derringer, Markon, Watson and Skodol10), an instrument specifically designed to assess pathological expressions of the five-factor traits. A recent meta-analysis of PID-5 studiesReference Al-Dajani, Gralnick and Bagby11 found good evidence that the measure is reliable and valid. However, notable in that review was the fact that most PID-5 research has been conducted with non-clinical samples.

There are at least three major advantages of moving toward a dimensional system. First, dimensional assessment yields greater precision of measurement.Reference Markon, Jonas and Huprich12 When the assessment process yields greater levels of reliability, then evidence for the validity of the measured construct improves. A measure of a diagnostic construct should be reliable, no matter how homogeneous or heterogenous, and the factor structure of the assessment device should be replicable and stable. Personality assessment researchers have shown quite consistently that, when comparing dimensions with categories, dimensions are more reliably measured.

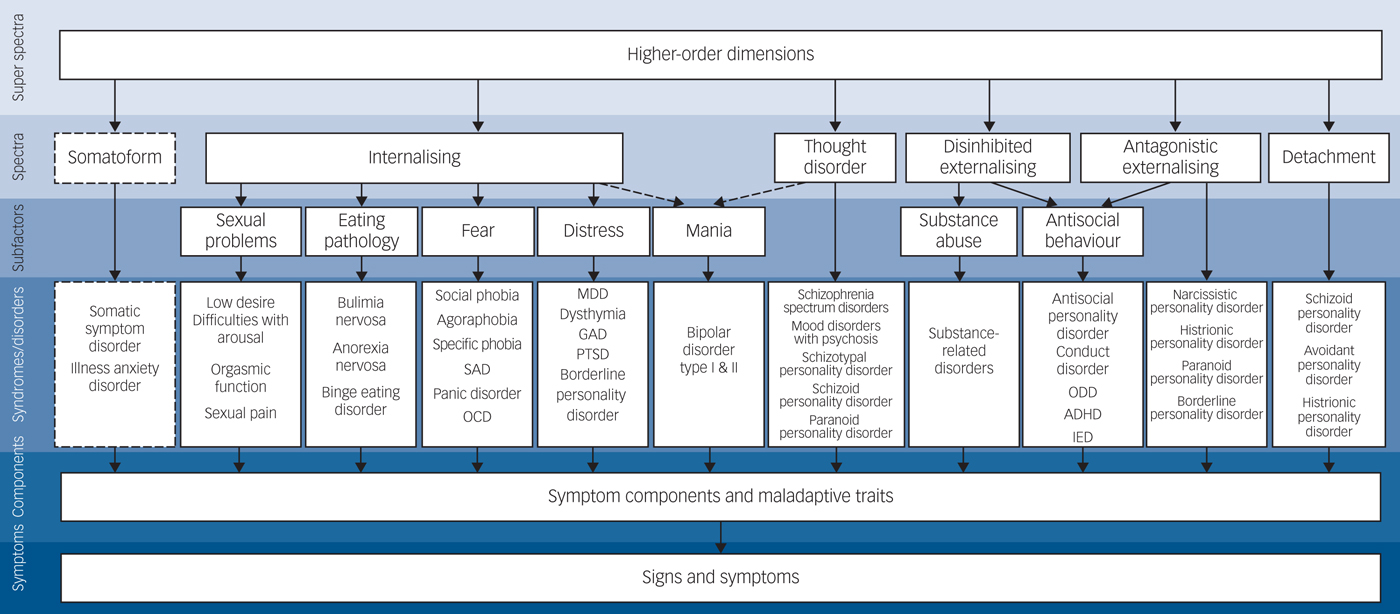

Second, some categories have questionable evidence as a valid constructReference Blashfield, Reynolds, Stennett and Widiger13 or regarding whether they are better placed within a spectrum with other related types of psychopathology.Reference Lenzenweger, Blaney, Krueger and Millon14 For years there has been considerable documentation of the comorbidity of many disorders (e.g. bipolar disorder versus borderline personality disorder or social phobia versus avoidant personality disorder), leading many to question whether there is a shared underlying cause or set of causes for such problems. Because the literature to date has not helped resolved the problem of comorbidity and how to better differentiate these conditions, and dimensional models help to better account for this problem, it would be reasonable for the field to consider a new framework that more effectively addresses this problem. This is the aim of a research consortium known as the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOPReference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff and Bagby15). Collectively, this group has derived a model based on a number of reviews of the empirical literature, diagnostic co-occurrence studies and large twin studies, and found a consistent pattern of co-occurrence and factor analytic organisation in a number of disorders (see Fig. 1).Reference Andrews, Pine, Hobbs, Anderson and Sunderland16–Reference Røysamb, Kendler, Tambs, Orstavik, Neale and Aggen20 For instance, within the detachment spectrum in the HiTOP framework, one could anticipate seeing schizoid, avoidant and dependent characteristics in the same person, and concerns about which diagnosis fits best, or whether two or more diagnoses are appropriate, would be minimised. If the application of dimensions is extended to all psychopathology, one could envision a diagnostic system in which pathology across a dimension would alert clinicians to other types of psychopathology that could be likely, and even anticipated, as the patient is being assessed and treated.

Fig. 1 Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology classification. ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; GAD, generalised anxiety disorder; IED, intermittent explosive disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; SAD, seasonal affective disorder.

Third, a dimensional system of personality pathology assessment may require clinicians to think more broadly about their patients than they do now.Reference Hopwood21 Assessing 25 trait facets (such as within the DSM-5 alternative model) would be time consuming, but has the potential of offering the clinician a more enhanced understanding of the patient than what might currently be happening by sole reliance on a categorical system. However, it may be argued that the all-too-often-used ‘personality disorder not otherwise specified’ category is essentially being perpetuated within this new trait framework. Yet, with traits being clearly defined within their empirically derived hierarchical structure and rated as such by the clinician, this approach could overcome the somewhat nebulous description that the personality disorder NOS category represents. Stated somewhat differently, this approach might promote a more idiographic and empirically grounded assessment of the patient's personality. This is important because failure to conduct idiographic assessment of patients has been a criticism among many clinicians, especially those operating within a psychodynamic framework.

Cautions in moving toward a dimensional framework

With a dimensional framework offering many advantages, it is understandable why some are saying that it is time to move completely toward a dimensional diagnostic system.Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff and Bagby15, Reference Hopwood, Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Widiger and Althoff22, Reference Tyrer, Crawford, Mulder, Blashfield, Farnma and Fossati23 However, there are a number of cautions that should be carefully considered before this transition happens.

Are traits the optimal framework?

There is the epistemological question of whether assessing traits is an optimal method for the classification of personality disorders. Diagnoses serve multiple purposes, including the identification of one disease or illness from another and the execution of a process by which to make this determination.Reference Silk24 Central to these purposes is the need to communicate something important about the patient to clinicians. Medicine has typically utilised diagnoses that are readily connected to the pathogenic condition underlying the illness (e.g. allergic rhinitis, myocardial infarction and stage III liver cancer). Although it could be hypothesised that pathological levels of trait facets within the DSM-5 or ICD-11 disinhibition trait domain could be associated with psychopathology broadly speaking, it is not always clear how this trait domain and its facets would be related to problems in personality. For instance, would excessive gambling or shopping be grounds for a DSM-5 personality disorder diagnosis if the individual assessed has high levels of impulsivity and no other disinhibition facets elevated? If the excessive gambling leads to decreased work productivity, financial stress and relationship distress, might this constitute a personality disorder? The DSM-5, for instance, has a category for impulse control disorders, so how would pathology in this one trait be grounds for a personality disorder diagnosis? The answer to this question is unclear. Similarly, elevations in the psychoticism domain have clear implications of psychopathology, but what makes this specific to personality pathology and not schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, major depressive disorder with psychotic features or delusional disorder?

As the DSM-5 section III model, ICD-11 proposal and HiTOP formulations all suggest, trait domains are the building blocks for a newly reformulated model of psychopathology. Yet, the field is far from broadly accepting a dimensional classification framework, and until then, it may fail to offer the degree of differentiation needed to separate a personality disorder from other conditions. By way of analogy, if one were to compare personality disorder trait structure to houses, a deconstructed, factor analytic approach would identify the ‘skeletal’ structure of a house by way of its core components: outer coverings (brick, stone, siding), connective material (mortar, fasteners, nails, brackets) and structural framework (wood, shingles, glass). These can all be put together a particular way to make up a house; however, many houses can be described by their style: colonial, bungalow, English Tudor, etc. It would seem important that we not lose those styles despite the difficulty in fitting every house into one of those categories, as certain styles do a good job describing what the house is like.

Traits may be a defensive response

KernbergReference Kernberg25, Reference Kernberg26 has noted that some traits may serve a defensive function, thus making the concept of a trait more fluid than what has been considered in many trait models. For instance, it is not too far of a mental stretch to see how trait facets such as withdrawal, intimacy avoidance, rigid perfectionism and unusual beliefs (i.e. PID-5 trait facets) could all describe certain constellations of cognitive, affective and behavioural features of a defence against unpleasant ideas or motives. Withdrawal and intimacy avoidance might be behavioural patterns that defend the self against feelings of shame or inadequacy, or fears of being hurt by others. Patients avoid close interpersonal relationships, yet engage well with others at work and in their immediate families, so differentiating the trait as more of a biogenetic or temperamental determinant of behaviour versus a defence mechanism would require careful consideration from the clinician.

Traits may be unconscious or implicit processes

KernbergReference Kernberg26 also observed that the traits may exist ‘in varying degrees on temperamental predispositions that influence past affective gratification or frustration of the person's own needs and desires in the context of adaptive relations with others’ (p. 148). In other words, a trait may be manifested from past experiences of satisfaction or frustration with others, such that the trait reflects unconscious, implicit processes of relating. Although the trait describes something about the person, it does not tell the clinician anything specific to why that trait is there and how it causes dysfunction. For instance, someone possessing higher levels of negative affectivity who has experienced physical and emotional trauma may have elevations in the facet of unusual beliefs, reflecting their adaptive position toward reality (i.e. ‘I must keep a watchful eye toward others on a daily basis because you never know when they might want to hurt me’), whereas another person with the same level of negative affectivity who had early exposure to sexual gratification might possess high levels of unusual beliefs about sexuality that again serve an adaptive purpose, but may or may not cause major maladaptation (i.e. ‘Looking at pornographic magazines is a good way for me to reduce my stress’, ‘Hooking up online is what I look forward to most weekends’). In both people, the traits are descriptive, but the implications about their origins and how they are addressed in treatment may vary considerably.

Personality disorders are fundamentally interpersonal and intrapsychic

Many models of personality pathology involve problems that are interpersonal or intrapsychic. In the aforementioned comparison of personality disorders to houses, it is important to remember that houses are not just houses, but are also homes wherein there are often many moving parts and dynamic systems. Borderline personality disorder, for instance, may be considered for pathological DSM-5 trait domains and facets in negative affectivity, emotional lability, impulsivity, separation insecurity, hostility, irresponsibility, risk-taking and perceptual dysregulation. However, treatment for borderline personality disorder almost always focuses on the ways in which these qualities lead to intrapsychic distress (e.g. ‘I am so scared by myself’, ‘I am pathetic and cannot act like a grown-up’) or interpersonal problems (e.g. ‘She is such a useless friend. I hate her’, ‘I don't care if I hurt him, he's such a jerk.’). Psychotherapy is not designed to modify most of the dimensional trait domains or their facets, but instead to reduce the problems that arise from internal or interpersonal distress. This does not mean the trait framework is of no value, but how the trait profile maps onto the types of problems that bring people into treatment is unclear. In fact, in the case of borderline personality disorder, it has been found that many of the symptoms or traits that bring people into treatment remain stable over many years,Reference Keuroghlian, Zanarini and Huprich27, Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg, Reich and Fitzmaurice28 but that the distress they bring and the magnitude of their impairment decreases beyond clinical necessity.

Fortunately, the alternative model of personality disorders in the DSM-5 asks clinicians to assess the self and other representations in what it described as levels of personality functioning. Self-functioning is evaluated in the domains of self-directedness and self-identity, whereas other (or interpersonal) functioning is evaluated in the domains of empathy and intimacy. The degree of impairment a person possesses is defined by the quality of their self and other representations. Somewhat similarly, in the ICD-11 proposal, clinicians are asked to assess patients for the severity of their personality pathology, such that individuals are determined to have a mild, moderate or severe personality disorder. In these descriptions, self and other functioning also are evaluated.Reference Tyrer, Crawford, Mulder, Blashfield, Farnma and Fossati23 A problem with these two approaches is that they potentially conflate impairment with the ways in which the self and other are represented. For instance, individuals with very low levels of self and other functioning can become quite successful if the conditions exist that reinforce their extant behaviour. Thus, although these components of the DSM-5 alternative model and ICD-11 proposal offer needed components for understanding self and other functioning, they may not adequately capture all there is to know about the individual's sense of self and interpersonal relatedness or offer ideas on how to improve self and relational functioning.

Demarcating pathological trait levels?

What exactly constitutes a pathological level of a trait has yet to be defined. Studies on the PID-5 and other trait-based instruments need to be conducted that would determine what benchmarks are associated with various levels of dysfunction. Herpertz et al Reference Herpertz, Huprich, Bohus, Chanen, Goodman and Mehlum30 have suggested that a system without clearly defined benchmarks leaves open the possibility that patients could be unfairly stigmatised by a personality disorder diagnosis determined by the clinician's idea that the trait level is too extreme and causing too much dysfunction. Thus, despite an empirically grounded framework of trait dimensions, it remains to be seen how well clinicians would utilise this approach and whether it would accurately detect maladaptation and dysfunction. Furthermore, would clinicians reliably apply the same criteria to determine malfunction and recognise whether a trait is pathological? If this cannot be done better than it has been with the DSM or ICD semi-structured diagnostic interviews, the field will not have advanced much. One alternative might be to ask the patient him or herself to complete a questionnaire about the traits (e.g. PID-5) to facilitate the clinician's diagnostic decision-making process. Although this might prevent some degree of subjectivity on the part of the clinician, it does not eliminate the problem of patients being able to self-report accurately.Reference Oltmanns, Turkheimer, Krueger and Tackett31 Furthermore, it is highly unlikely that clinicians would utilise such a self-report measure, given its length and the general tendency of clinicians to utilise their assessment of patients' self and other functioning and their relationship with them to affect their process for detecting personality pathology.Reference Westen32

A diagnostic system based mainly on deconstructed matrices of self-reports?

There are very few, if any, diagnostic frameworks in place that are centrally organised around patients' reports about themselves. Diagnosis has always relied upon the provider's evaluation of the patient and the use (and frequent requirement) of a medical test or particular examination to confirm a diagnosis. Psychology and psychiatry do not exist at this level of sophistication, and it is unreasonable to place that requirement into a psychiatric diagnostic system at the current time. However, to utilise a mainly self-reported trait system that is derived from statistical variation and covariation (in factor analysis) may miss important aspects of functioning that are assessed by intrapersonal and interpersonal dynamics. Regretfully, there are some signs that these latter issues are already deemed unimportant in a dimensional system. Kotov et al Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff and Bagby15 write, ‘cognitive-behavioural therapy and even disorder-specific therapies have been found to reduce symptoms of various internalizing conditions…’ and that ‘selective serotonin specific reuptake inhibitors and cognitive-behavioural therapy appears to be a shared feature of internalizing disorders…A quantitative nosology fits naturally with this practice by providing a systematic list of symptom targets for pharmacotherapy' (p. 15). These ideas suggest that symptom reduction as recognised within the trait framework by way of cognitive behavioural treatment and pharmacotherapy is a central clinical outcome of this classification system. Utilising just medications for treating personality pathology is not well supported in the literature on personality disorders, in which psychotherapy (with an emphasis on self and other functioning) is often seen as a necessary component of treatment.Reference Oldham, Skodol and Bender33 More importantly, these ideas represent the worst of a deconstructed system – that the person's problems can be reduced to biological functioning and as originating from a maladaptive constellation of biogenetically determined thoughts–feelings–behaviour. Although such ideas have not been presented in other dimensional systems, it is quite alarming that authors of this dimensional system would suggest treatment should be deconstructed as well, so that the symptom constellation becomes the focus of clinical attention.

Categories will not go away

Finally, there is the question of what to do with existing categories in a dimensional system. Some have suggested that the categories should disappear.Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff and Bagby15, Reference Hopwood, Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Widiger and Althoff22 However, others recognise the value of specific categories,Reference Herpertz, Huprich, Bohus, Chanen, Goodman and Mehlum30 and there are decades of research on a number of existing categories that yield meaningful information about the nature of psychopathology and its treatment. It is hard to imagine how these categories will disappear entirely from the clinical and empirical literature.Reference Clarkin and Huprich34 Humans naturally form categories, as they are highly adaptive and help individuals understand the world and how it generally operates. Referring again to the house analogy, some styles or types of houses are quite useful in helping people understand what they are like (e.g. ranch, colonial, etc.). In fact, the dimensional classification system proposed by Tyrer et al Reference Tyrer, Crawford, Mulder, Blashfield, Farnma and Fossati23 requires categorical decisions to be made: Is the level of severity that of a personality difficulty (yes or no), personality disorder (yes or no), complex personality disorder (yes or no) or severe personality disorder (yes or not)? Subsequently, Tyrer et al propose exemplars of what each level of severity might look like. How does this not lead to prototypical representations of levels of severity? For instance, would not a suicidal person whose sense of self is highly unstable and who has very poor defensive functioning automatically be determined to have a severe personality disorder that might be akin to borderline personality disorder? Even with dimensions, the use of categorical and prototypical thinking is inevitable.

Moving forward

Dimensional systems of classification are clearly superior psychometrically over extant categorical systems. However, intrapersonal and interpersonal problems are core features of personality pathology that may not be well represented in a trait domain system. Additionally, certain categories remain clinically useful and an important part of the diagnostic nomenclature (e.g. borderline, antisocial personality disorder). With the development of section III of DSM-5, the ICD-11 proposal and the creation of HiTOP, the field may be able to move to a more empirically informed way of assessing personality and psychopathology that can address many of the problems with the categorical system. Although these frameworks are a big step forward and may ultimately be accepted, they are fraught with risks of losing important concepts and processes that are associated with personality disorders (and are considered as part of the core components of many categories). More importantly, a dimensional system ultimately must sometimes be used in a categorical manner to diagnose and treat a disorder.

What is the solution? Unfortunately, this is not at all clear, and the magnitude of difference at times between those favouring categories and those favouring dimensions has a politically polarised feel to it. However, it might be best to begin with what many know and believe. As a first step, it would seem both dimensions and categories should continue to be part of the current diagnostic nomenclature, such that clinicians who identify a particular category that fits the patient well might legitimately be allowed to use it, while at the same time, the many (in fact, majority) patients who do not neatly fit into an extant category can be diagnosed within a trait system. By way of rapprochement, the field of personality disorders could advance considerably by temporarily accepting this type of system for classifying and diagnosing personality disorders. Moving forward, researchers should continue to compare trait assessment with categorical or prototype methods of assessment and evaluate whether a particular constellation of traits consists in a robust manner among a group of patients that it would make more sense to use a categorical or prototype label to describe them (e.g. borderline, narcissistic). Additionally, an assessment of the trait patterns observed in patients might also derive new categories or prototypes that have not been well-articulated in the literature.

Second, it has been accepted that the number of pathological personality criteria a person possesses is associated with poor overall functioning.Reference Meehan, Clarkin and Huprich35 Severity is rooted in the well-established idea that impairments in self and other representations are essential features of personality disorders.Reference Hopwood, Malone, Ansell, Sanislow, Grilo and McGlashan36 Self and other functioning have much potential to help make the ICD-11 and the alternative model of DSM-5 clinically useful and, if personality disorder diagnosis and assessment is to advance, it is incumbent upon personality disorder researchers to focus as intensely on the phenomenological aspects of personality pathology that rely less on self-reports of traits but more on internal processes, dynamics, contextual variables and relational patterns which seem to be a significant component of what constitutes personality pathology. By going beyond trait dimensions, a more comprehensive and wholistic assessment of the person is possible, while simultaneously utilising the dimensional scaffolding on which to locate the individual person.

Another means of advancing beyond categorical and dimensional models of classification would be to offer a more comprehensive description of personality and its pathology than what currently exists in the DSM-5 or the original ICD-11Reference Tyrer, Crawford, Mulder, Blashfield, Farnma and Fossati23 proposal. For instance, the DSM-59 states that a personality disorder is a pattern of conscious experience and behaviour that significantly differ from cultural expectations, affecting two or more of the following areas: cognition, affectivity, interpersonal functioning and impulse control. However, a review of the personality assessment literature reveals a much more comprehensive description of what to evaluate in personality than do the diagnostic manuals.Reference Bender, Morey and Skodol37–Reference Weiner and Greene40 This includes an expanded assessment of those temperament, biological/familial and trait domains that are part of the person's make-up, the person's self-representation, relational patterns and quality, affective experience and regulation, impulse control, coping or defence mechanisms, reality testing and judgement, contextual and cultural variables and an assessment of how the person applies values and moral reasoning to their daily functioning. Anchoring level of severity into a more comprehensive assessment of personality pathology would advance the field considerably, as most broad-band approaches to personality assessment appreciate that personality has both dynamic and static components, and that what is assessed at any given time is likely to reflect internal processes that regulate self-presentation, which can often be limited by individuals' immediate awareness of themselves. Moving beyond categories and dimensions requires a conceptualisation of personality disorder that captures the breadth, depth and dynamics of the personality system – something a number of personality researchers already endorse.Reference Kernberg41–Reference Hopwood, Zimmermann, Pincus and Krueger45 These more expansive perspectives can readily accommodate trait assessment as a matrix upon which personality pathology can be found and subsequently integrated with other types of psychopathology, much as the HiTOP initiative seeks to do.

Concluding comments

Moving beyond the limits of the existing categorical system is challenging, yet needed. A dimensional framework rooted in traits offers an empirically grounded taxonomy that is parsimonious. Yet, traits do not necessarily provide the optimal framework upon which to ground a new system. How to move beyond the categorical and dimensional debate is challenging, although thinking more carefully about what personality is, and how it becomes pathological, can potentially yield a more clinically useful perspective. Where the field ultimately settles with regard to diagnosing and assessing personality pathology and disorders is unknown, and a rapprochement is most needed. It is time to evolve to the next level.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.