6.1

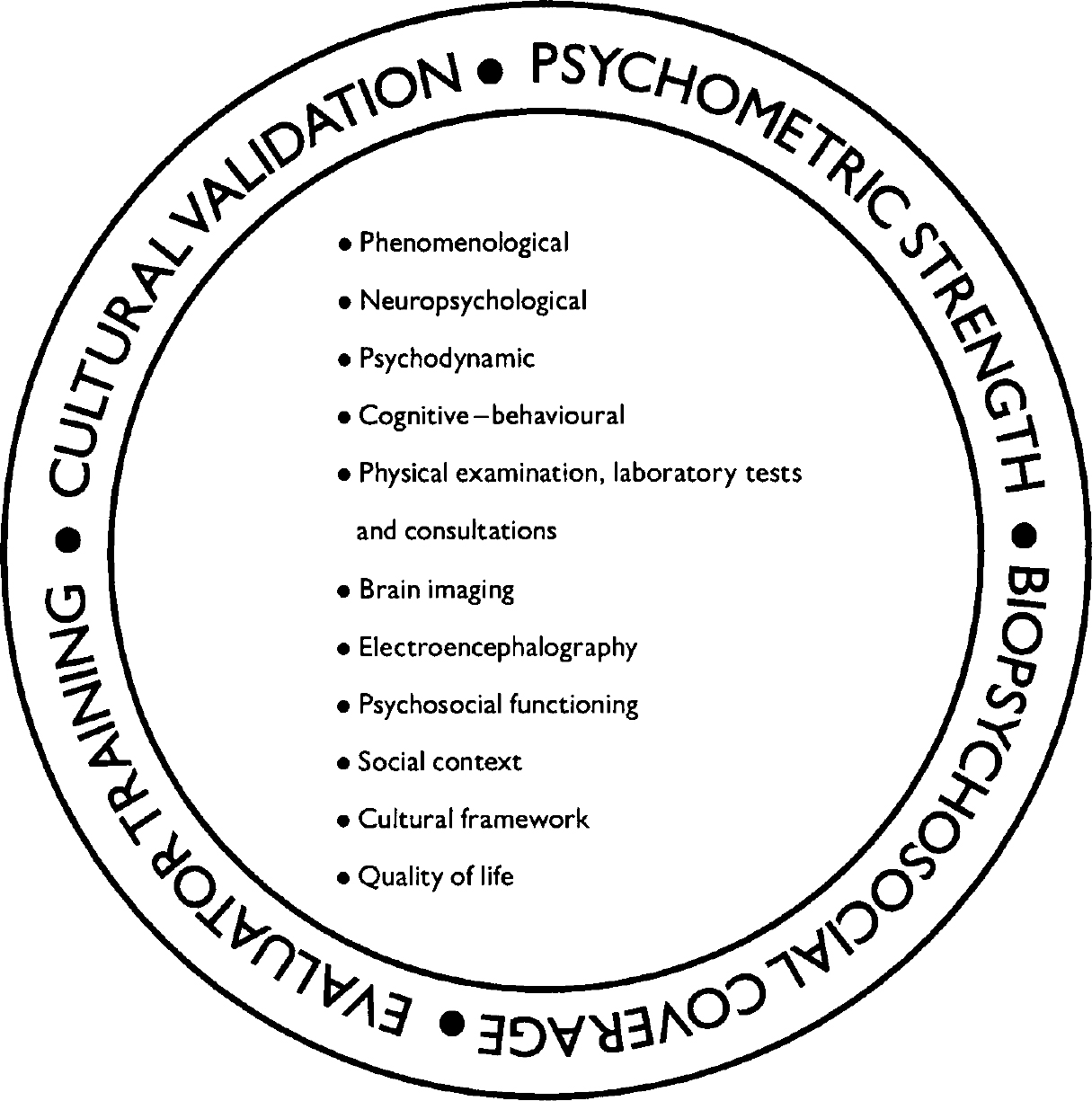

Supplementary procedures (Fig. 6.1) can be used to obtain a comprehensive assessment of social, cultural and other contextual factors influencing the occurrence, presentation, course or treatment of clinical disorders. They may also be useful for measuring social and occupational functioning and participation, social support, family adjustment, life events and quality of life. In these, as in all clinical assessments, the cultural framework should be systematically considered.

Fig. 6.1 Supplementary assessment procedures.

6.2

The purposes of these supplementary assessments are:

-

(a) to document areas and degrees of impairment in social and occupational functioning for the purposes of comprehensive diagnosis, prognosis, care planning and disability compensation;

-

(b) to describe patients' social support systems or networks, personal and environmental resources, and recent and remote stressful life events for the purposes of diagnosis and treatment;

-

(c) to assess the family's perceptions of the patient's problems, their impact on the patient, and their consequences for family functioning;

-

(d) to assess quality of life for a broad assessment of well-being and to ensure that attention is paid to what is most meaningful to the patient (e.g. family supports, religious beliefs).

6.3

Various types of supplementary assessment procedures should be considered for use in evaluating these domains, including clinician-rated, self-rated and family-rated scales, checklists, and semi-structured interview methods.

6.4

Choice of a supplementary assessment procedure should be based on a consideration of the purpose intended (e.g. to aid in determining level of treatment needed, to identify particular targets of treatment); the breadth or specificity desired (e.g. global assessment of functioning v. specific measure of social functioning); the kind of patient, or setting of evaluation (e.g. adults with schizophrenia, married couples, people in institutional care); and the resources available (e.g. trained interviewer, or clerical scorer of self-report questionnaire).

6.5

Global assessment instruments provide an overall rating of clinical state or functioning. A trained clinician is usually needed to make the assessment. The rating is usually made on a single continuous scale and can be used to monitor clinical improvement over time.

6.6

Detailed measures of social functioning should be used to assess clinical state and health status and to determine level of care (e.g. in-patient, out-patient or long-term residential treatment). The most important areas to assess are interpersonal functioning, occupational functioning, self-care and broader social participation, keeping in mind that their relative importance varies across cultures.

6.7

Important areas of social context to be assessed include socio-economic status (for example through head of household's occupation and education), social supports and stressors, and access to care (including financial, insurance, geographical, transportation and cultural barriers).

6.8

Scales and instruments to appraise marital and family functioning as well as sexual health are useful in planning couple or family therapy.

6.9

It is often important, particularly in multicultural societies, to assess the cultural framework of the experience of illness explanations and help-seeking behaviours. Consideration of the patient's explanatory models can be valuable for both valid diagnosis and effective care planning.

6.10

The need to broaden the information base of health status assessment has led to the development of quality-of-life measures. These refer predominantly to the individual's subjective perception of satisfaction with and position in life in relation to that individual's goals, expectations, standards and aspirations.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.