The prescribing of diamorphine (pharmaceutical heroin) as part of treatment for heroin addiction initially appears counter-intuitive. Addiction is increasingly recognised as a chronic relapsing disorder Reference McLellan, Lewis, O'Brien and Kleber1 for which effective treatments exist. Reference Strang, Babor, Caulkins, Fischer, Foxcroft and Humphreys2 However, public responses to addiction tend to polarise around addiction as ‘badness’ or addiction as ‘illness’, and counter-intuitive treatments often generate strongly felt passions associated with these differing frames of reference. When debate gets heated, it is particularly important for science to contribute cool-headed analysis.

Fifteen years ago, Bammer et al Reference Bammer, Dobler-Mikola, Fleming, Strang and Uchtenhagen3 considered this issue at which time there was only one randomised trial (from the UK during the 1970s) investigating heroin-prescribing in an unsupervised clinical situation Reference Hartnoll, Mitcheson, Battersby, Brown, Ellis and Fleming4 and one small randomised trial from Switzerland of a new approach of fully supervised self-administration of the prescribed heroin. Reference Perneger, Giner, del and Mino5 This latter approach of entirely supervised administration of every injected dose has become standard clinical practice in a new generation of well-designed and executed trials – a further five randomised clinical trials internationally over the past 15 years (see below).

Diamorphine has been prescribed at different times in treatment of heroin addiction for more than a century, in countries that originally included the USA Reference Musto6 and has continued throughout the century, to a variable extent, in the UK, Reference Strang and Gossop7 but it was not until the work of Uchtenhagen and his colleagues in Switzerland in the 1990s that the approach of supervised injectable heroin (SIH) treatment was properly established. Reference Rehm, Gschwend, Steffen, Gutzwiller, Dobler-Mikola and Uchtenhagen8–Reference Uchtenhagen10

Two features characterise the new approach. First, SIH treatment is not a first-line treatment, but an option for patients who have not responded to standard treatments such as oral methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) or residential rehabilitation. Second, all injectable doses (typically 150–250 mg diamorphine per injection) are taken under direct medical or nursing supervision, thereby ensuring compliance, monitoring, safety and prevention of possible diversion of prescribed diamorphine to the illicit market; this requires the clinics to be open several sessions per day, every day of the year. This model of treatment involves screening and appropriate patient selection, structured induction and monitoring, and a high level of support and interaction with staff – thus significantly different from the ‘public health’ approach of open-access supervised injecting rooms. Reference Wright and Tompkins11 In contrast, SIH treatment is a high-cost, low-volume specialist intervention.

The Cochrane Collaboration has conducted a systematic review of all heroin-prescribing trials. Reference Ferri, Davoli and Perucci12 While the Cochrane review compared ‘SIH treatment plus methadone v. oral MMT’, based on trials of SIH treatment, a considerable portion of the reported comparisons have drawn on the findings from a wider group of heroin prescribing randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including ‘heroin provision of various modality and route of administration’, i.e. supervised and unsupervised prescribing practices and prescribing of both injectable and inhalable heroin.

The aims of this paper are: (i) to undertake a systematic review and meta-analysis of a defined narrow group of randomised trials of SIH prescribing and (ii) to examine the political and scientific response to the published findings.

Method

Search strategy

The review was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines (www.prisma-statement.org). The search strategy targeted studies that reported on the effect of SIH treatment in a range of outcome domains among individuals with heroin-dependence unresponsive to standard treatments. Computer-based internet databases used for this search included MEDLINE (PubMed database), Web of Science and Scopus. There were no language or publication year restrictions. The combinations of keywords used in the database search included ‘addiction’, ‘assisted’, ‘supervised’, ‘dependence’, ‘diacetylmorphine’, ‘diamorphine’, ‘heroin’, ‘maintenance’, ‘prescription’ and ‘treatment’. The initial data searches and screening of irrelevant abstracts were conducted by T.G. Subsequent data checking and searches were overseen by N.M. and J.S. Lead clinicians and/or researchers who have been at the forefront of testing and trialling SIH trials co-authored this paper.

Inclusion criteria and selection of studies

The methodology was designed to collect evidence in a sequential and logical manner. The review has a clear focus on evidence of SIH treatment efficacy as well as allowing a broad scope for learning about the scientific and political response to the published findings. Only studies that had the key search terms in the abstract and also had opiate use, retention in treatment, mortality and side-effects as outcome variables were considered. Thus, methodological papers were excluded. Papers were also excluded if they were assessing the pre-existing unsupervised heroin treatment provision, which focused on policy aspects, which were only reporting profile of trial participants or which were separately reporting on measures of cost-effectiveness, community perspectives and patient satisfaction or longer-term (beyond the trial follow-up period) effects.

Data extraction

Information extracted from each study included the location of the study, author names, year of publication, sample size, groups studied, time to follow-up, outcome measures and effect-size estimates.

Statistical analysis

Mantel–Haenszel random effects pooled risk ratios and corresponding 95% CI for SIH treatment patients v. comparison groups were calculated using Review Manager 5.2 for Windows 7 with fuller (compared with the latest Cochrane review of 2011) outcome data. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed through the I 2 statistic. Lastly, funnel plots were used to assess potential publication bias for the meta-analyses.

Results

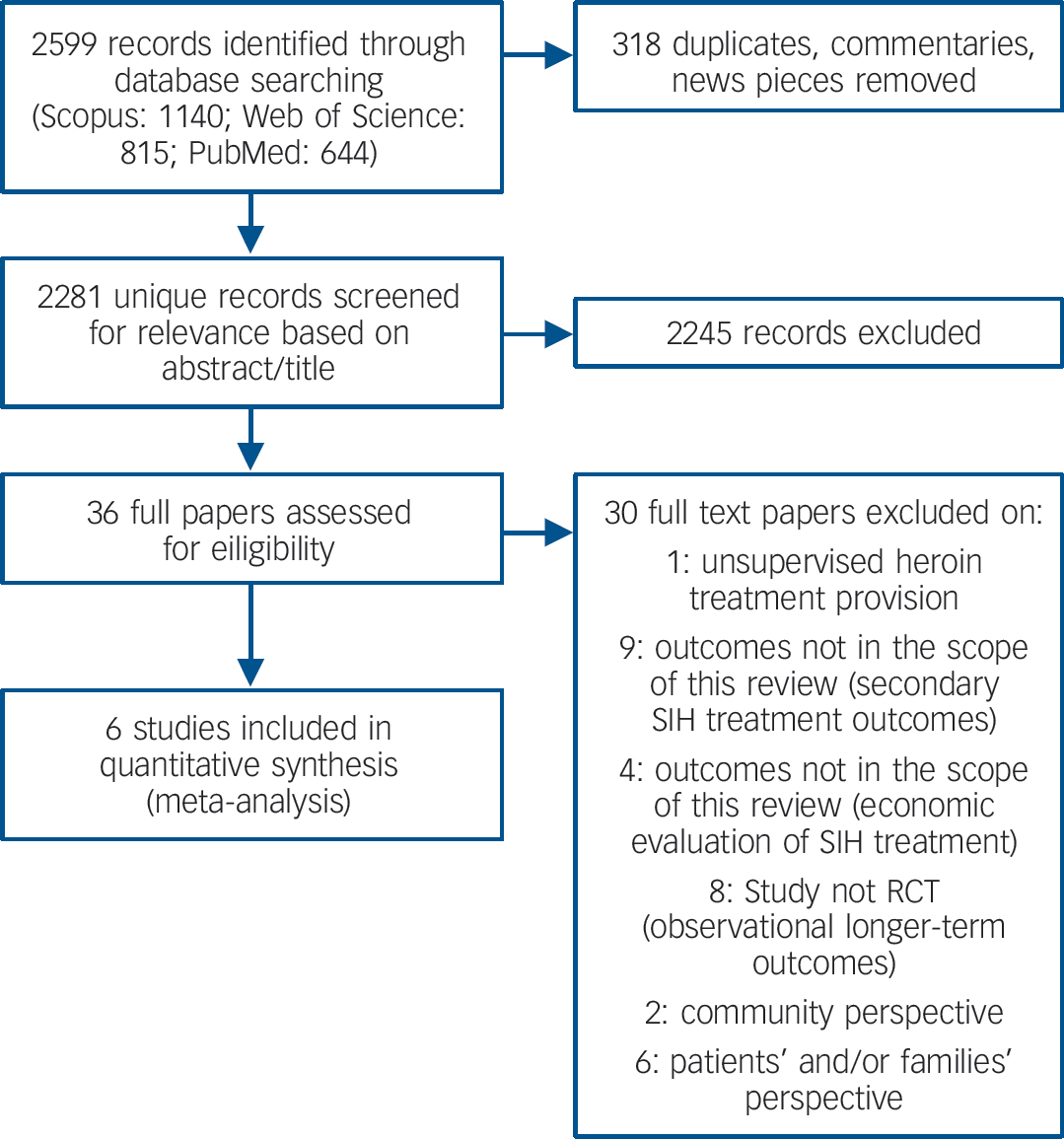

A total of 2599 records were identified using the search terms (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Selection of studies for meta-analysis.

All papers were in English language. Table 1 summarises the six trials included in the review.

Table 1 Six randomised trials of supervised injectable heroin (SIH) (plus flexible supplementary doses of oral methadone): key features and outcomes

| Main paper | Country | Sample size; groups studied |

Time to follow-up |

Cochrane risk of bias

Reference Ferri, Davoli and Perucci12

using five criteria recommended by the Cochrane Handbook Reference Higgins and Green18 |

Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perneger et al Reference Perneger, Giner, del and Mino5 | Switzerland |

n = 51 SIH (+OM): n = 27 OM, detox, rehab: n = 24 |

6 months | Random sequence generation Allocation concealment Incomplete outcome data Selective reporting Blinding (objective outcomes) Blinding (subjective outcomes) |

L L L U H H |

Retention: SIH: 93% v. OM 92% Self-reported illicit heroin use: SIH: 22%, OM: 67% (P = 0.002) SAEs data not reported |

| van den Brink et al Reference van den Brink, Hendriks, Blanken, Koeter, van Zwieten and van Ree13 |

The Netherlands | Injectable trial: n = 174 SIH (+OM): n=76 OM: n = 98 (also SInhH trial, n = 75) |

12 months | Random sequence generation Allocation concealment Incomplete outcome data Selective reporting Blinding (objective outcomes) Blinding (subjective outcomes) |

U L L L L L |

Retention: SIH 72% v. OM 85% Self-reported 40% improvement in at least one domain (physical, mental, social): SIH 56% v. OM 31% (P = 0.002) SAEs: reported data limited to 11 SAEs (two definitely or probably and nine possibly related to injectable heroin) |

| March et al Reference March, Oviedo-Joekes, Perea-Milla and Carrasco14 | Spain |

n = 62 SIH (+OM): n = 31 OM: n = 31 |

9 months | Random sequence generation Allocation concealment Incomplete outcome data Selective reporting Blinding (objective outcomes) Blinding (subjective outcomes) |

U L L L U U |

Retention: SIH 74% v. OM 68% Self-reported illicit heroin use in past 30 days (mean days): SIH = 8.3 v. OM = 16.9 (P = 0.02) SAEs: SIH = 7 (two unrelated and five probably or definitely related to study drug) v. OM = 7 |

| Haasen et al Reference Haasen, Verthein, Degkwitz, Berger, Krausz and Naber15 | Germany |

n = 1015 SIH (+OM): n = 515 OM: n = 500 |

12 months | Random sequence generation Allocation concealment Incomplete outcome data Selective reporting Blinding (objective outcomes) Blinding (subjective outcomes) |

L L L L U U |

Retention: SIH 67% v. OM 40% Improvement in drug use (measured by either UDS and self-report): SIH 69%, OM 55% (P<0.001) Improvement in physical/mental health: SIH 80%, OM 74% (P = 0.023) Combined reduced drug use and improved physical/mental health (responder): SIH 57% v. OM 45% (P<0.001) SAEs: SIH = 177 (58 possibly, probably or definitely related to study drug) v. OM = 15 |

| Oviedo-Joekes et al Reference Oviedo-Joekes, Brissette, Marsh, Lauzon, Guh and Anis16 |

Canada |

n = 251 SIH (+OM): n = 115 OM: n = 111 (also SIHM+OM, n = 25) |

12 months | Random sequence generation Allocation concealment Incomplete outcome data Selective reporting Blinding (objective outcomes) Blinding (subjective outcomes) |

L L L L L L |

Retention: SIH 88% v. OM 54% (P<0.001) Self-reported reduction in illicit drug use or other illegal activities (improvement of 20% for either domain): SIH = 67%, OM = 48% (P = 0.004) SAEs: SIH = 51 v. OM = 18 |

| Strang et al Reference Strang, Metrebian, Lintzeris, Potts, Carnwath and Mayet17 | England |

n = 127 SIH (+OM): n = 43 OOM: n = 42 (also SIM+OM, n = 42) |

6 months | Random sequence generation Allocation concealment Incomplete outcome data Selective reporting Blinding (objective outcomes) Blinding (subjective outcomes) |

L U L L L L |

Retention: SIH (or other treatment) 88% v.

OOM 69% Reduction in ‘street’ heroin – 50% or more negative UDS during weeks 14–26 (responder): SIH 66% v. OOM 19% (P<0.0001) SAEs: SIH = 7 (two probably related to study drug) v. OOM = 9 |

SAE, serious adverse event; OM, oral methadone; OOM, optimised oral methadone; SIM, supervised injectable methadone; SinhH, supervised inhalable heroin; SIHM, supervised injectable hydromorphone. L, low risk of bias; U, unclear; H, high risk of bias.

In addition to the six main papers from the individual trials, a broader set of papers is available, reporting other data such as secondary SIH treatment outcomes, observational longer-term outcomes, health economic data, family perspectives, community perspectives and patient satisfaction. Alongside the results of a meta-analysis of the effects of SIH treatment, this broader set of papers is outlined, although not integrated in our formal analysis for the reasons listed in Table 2.

Table 2 Thirty papers excluded from this review presented in chronological order (from the most recent to the oldest), country and reason for exclusion

| Paper | Country | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Byford et al Reference Byford, Barrett, Metrebian, Groshkova, Cary and Charles19 | England | Outcomes not in the scope of this review (health economics) |

| 2 Groshkova et al Reference Groshkova, Metrebian, Hallam, Charles, Martin and Forzisi20 | England | Patients' perspective |

| 3 Verthein et al Reference Verthein, Schafer and Degkwitz21 | Germany | Study not RCT (longer-term outcomes) |

| 4 Vogel et al Reference Vogel, Knopfli, Schmid, Prica, Strasser and Prieto22 | Germany | Outcomes not in the scope of this review (secondary outcomes) |

| 5 Nosyk et al Reference Nosyk, Guh, Bansback, Oviedo-Joekes, Brissette and Marsh23 | Canada | Outcomes not in the scope of this review (health economics) |

| 6 Marchand et al Reference Marchand, Oviedo-Joekes, Guh, Brissette, Marsh and Schechter24 | Canada | Patients' perspective |

| 7 Verthein et al Reference Verthein, Haasen and Reimer25 | Germany | Study not RCT (longer-term outcomes) |

| 8 Blanken et al Reference Blanken, Hendriks, van Ree and van den Brink26 | The Netherlands | Study not RCT (longer-term outcomes) |

| 9 Blanken et al Reference Blanken, van den Brink, Hendriks, Huijsman, Klous and Rook27 | The Netherlands | Patients' perspective |

| 10 Eiroa-Orosa et al Reference Eiroa-Orosa Haasen, Verthein, Dilg, Schafer and Reimer28 | Germany | Outcomes not in the scope of this review (secondary outcomes) |

| 11 Haasen et al Reference Haasen, Verthein, Eiroa-Orosa Schafer and Reimer29 | Germany | Outcomes not in the scope of this review (secondary outcomes) |

| 12 Karow et al Reference Karow, Reimer, Schafer, Krausz, Haasen and Verthein30 | Germany | Outcomes not in the scope of this review (secondary outcomes) |

| 13 Lasnier et al Reference Lasnier, Brochu, Boyd and Fischer31 | Canada | Community perspectives |

| 14 Miller et al Reference Miller, McKenzie, Lintzeris, Martin and Strang32 | England | Community perspectives |

| 15 Oviedo-Joekes et al Reference Oviedo-Joekes, March, Romero and Perea-Milla33 | Spain | Study not RCT (longer-term outcomes) |

| 16 Oviedo-Joekes et al Reference Oviedo-Joekes, Guh, Brissette, Marchand, Marsh and Chettiar34 | Canada | Outcomes not in the scope of this review (secondary outcomes) |

| 17 Oviedo-Joekes et al Reference Oviedo-Joekes, Guh, Marsh, Brissette, Nosyk and Krausz35 | Canada | Outcomes not in the scope of this review (secondary outcomes) |

| 18 Scafer et al Reference Scafer, Eiroa-Oroa, Verthein, Dilg, Haasen and Reimer36 | Germany | Outcomes not in the scope of this review (secondary outcomes) |

| 19 Haasen Reference Haasen37 | Germany | Outcomes not in the scope of this review (health economics) |

| 20 Perea-Milla et al Reference Perea-Milla, Aycaguer, Cerda, Saiz, Rivas-Ruiz and Danet38 | Spain | Outcomes not in the scope of this review (secondary outcomes) |

| 21 Haasen et al Reference Haasen, Eiroa-Orosa Verthein, Soyka, Dilg and Schafer39 | Germany | Outcomes not in the scope of this review (secondary outcomes) |

| 22 Romo et al Reference Romo, Poo and Ballesta40 | Spain | Patients' perspective |

| 23 Miller et al Reference Miller, Forzisi, Lintzeris, Zador, Metrebian and Strang41 | England | Patients' perspective |

| 24 Verthein et al Reference Verthein, Bonorden-Kleij, Degkwitz, Dilg, Kohler and Passie42 | Germany | Study not RCT (longer-term outcomes) |

| 25 Dursteler-Macfarland et al Reference Dursteler-Macfarland, Stohler, Moldovanyi, Rey, Basdekis and Gschwend43 | Switzerland | Patients' perspective |

| 26 Dijkgraaf et al Reference Dijkgraaf, van der Zanden, de Borgie, Blanken, van Ree and van den Brink44 | The Netherlands | Outcomes not in the scope of this review (health economics) |

| 27 Rehm et al Reference Rehm, Frick, Hartwig, Gutzwiller and Uchtenhagen45 | Switzerland | Study not RCT (longer-term outcomes) |

| 28 Guttinger et al Reference Guttinger, Gschwend, Schulte, Rehm and Uchtenhagen46 | Switzerland | Study not RCT (longer-term outcomes) |

| 29 Rehm et al Reference Rehm, Gschwend, Steffen, Gutzwiller, Dobler-Mikola and Uchtenhagen8 | Switzerland | Study not RCT (longer-term outcomes) |

| 30 Hartnoll et al Reference Hartnoll, Mitcheson, Battersby, Brown, Ellis and Fleming4 | England | Unsupervised heroin treatment provision |

Six randomised trials in six countries over 15 years: synthesis of findings

In this section, we present the trials in historical sequence. The early heroin trial from the 1970s Reference Hartnoll, Mitcheson, Battersby, Brown, Ellis and Fleming4 was not included since this was not based on the new approach of supervised injecting. The series of SIH treatment trials commences with the 1998 Perneger trial in Switzerland, the crucible of the new supervised injecting clinic approach. All of the new randomised trials summarised in this article have taken as their study participants chronic heroin-dependent individuals who have repeatedly failed in orthodox treatment (either currently still failing in treatment as evidenced by continued regular heroin injecting, or alternatively currently no longer engaged in treatment), apart from a subsample of the German study, and they have included randomised comparison with the standard treatment of oral MMT. Generally, the results were consistent and each trial has progressively strengthened the evidence-base for this new treatment approach.

(a) Switzerland, 1998

This small study (n = 51) was important as the first randomised trial of this new supervised treatment approach. Reference Perneger, Giner, del and Mino5 Participants were studied over a 6-month period of injected diamorphine or oral MMT. The two groups had equivalent retention, but the diamorphine-prescribed group had significantly greater reductions in illicit heroin use and in crime after 6 months of treatment. Continued illicit heroin use was self-reported by only 22% of the heroin-prescribed group v. 67% of the control group. This early trial contributed to establishing the feasibility of the randomised trial study design, the potential acceptability of the supervised injectable clinic modality, the high doses of diamorphine maintenance that could safely be administered, as well as the good short-term outcome at 6 months.

(b) The Netherlands, 2003

The two Dutch multi-site randomised trials Reference van den Brink, Hendriks, Blanken, Koeter, van Zwieten and van Ree13 constituted a significant step-change in the evidence-base, bringing sufficient sample size (n = 594) and study rigour to reach more robust conclusions. One of the trials studied the efficacy and safety of injectable diacetylmorphine (n = 174), the other the efficacy and safety of inhalable diacetylmorphine (n = 375) and will not be considered further in this article. Retention rate for MMT at 12 months was higher (85%) than for SIH (72%), but a much larger proportion of the heroin- prescribed group were ‘responders’ on the pre-determined composite scale of response (57% v. 32%). In addition, the Dutch trials showed that SIH was cost-effective for this target population. Reference Dijkgraaf, van der Zanden, de Borgie, Blanken, van Ree and van den Brink44 The study method and the results from the Dutch trial guided the construction of the later trials reported in this article.

(c) Spain, 2006

This small (n = 62) randomised trial was undertaken in Andalucia Reference March, Oviedo-Joekes, Perea-Milla and Carrasco14 and found equivalent retention, and significantly greater reduction in self-reported illicit heroin use in the diamorphine group at their selected 9-month follow-up point. Despite the small sample size and the continued reliance on self-report, these findings provided further evidence of benefit to previous studies and also contributed the perspectives of the families of the heroin addicts in SIH treatment. Reference Romo, Poo and Ballesta40

(d) Germany, 2007

This multi-site trial Reference Haasen, Verthein, Degkwitz, Berger, Krausz and Naber15 is the largest conducted to date (n = 1015), and found slightly higher retention in the heroin compared with the methadone group. It found greater proportions of the heroin-prescribed group reporting reduced heroin use and being ‘responders’ on the multidimensional outcome measure. An advance in this trial was the attention to ensuring good dosage for participants randomised to oral MMT (thus addressing concern that the apparent advantage of heroin-prescribing may be an artefact of suboptimal treatment in the control group). This trial also incorporated various other study elements (two different recruitment strands; and two styles of counselling therapy – neither of which was associated with meaningful differences in outcome). This trial was the first to include objective laboratory test results for illicit heroin, but these were not available across all participants, were only incorporated into the composite score and were not reported separately.

(e) Canada, 2009

The Canadian NAOMI (North American Opiate Medication Initiative) trial (n = 226), a two-site randomised trial, Reference Oviedo-Joekes, Brissette, Marsh, Lauzon, Guh and Anis16 was the first of the randomised trials to be conducted outside Europe and was carried out in severely affected participants not currently in treatment but with multiple previous treatment attempts. Significantly higher rates of retention (in SIH or other treatment) and clinical response scores occurred in those randomised to diamorphine. This trial also included a small subsidiary arm (n = 25) that was an exploratory double-masked evaluation of injectable hydromorphone and which included objective laboratory urinanalysis, and the results showed broadly equivalent benefits. Reference Oviedo-Joekes, Guh, Brissette, Oviedo-Joekes, Guh and Brissette47

(f) England, 2010

The UK three-site RIOTT (Randomised Injectable Opioid Treatment Trial) Reference Strang, Metrebian, Lintzeris, Potts, Carnwath and Mayet17 was important as the first trial to be conducted with laboratory illicit opioid test results as the pre-declared primary outcome measure. This three-way randomised trial compared two forms of supervised injectable maintenance (SIH and supervised injectable methadone maintenance) against an optimised version of oral MMT. Although the sample size was modest (n = 127 across the three groups), the investigators had the benefit of the previous trials to guide calculations of sample size and power, as well as improved laboratory analytical methods involving assay for papaverine and other components of illicit heroin. Reference Paterson, Lintzeris, Mitchell, Cordero, Nestor and Strang48 Good retention was achieved in all groups. At months 4–6, the heroin-treated group was significantly more likely to provide urine specimens negative for markers of illicit heroin than the optimised MMT group. This trial also reported on the speed of onset of the benefit observed in the heroin-treated group (as had the Dutch trial), and again benefits were evident within 2 months of treatment.

Effects of SIH treatment

Opiate use outcome data

Across the trials, different opiate use reduction (or abstinence) outcome measures were used, which prevents exploration of the pooled results in relation to this outcome. Nonetheless, there was a positive effect of SIH on illicit heroin use reported by each individual study. Reference Perneger, Giner, del and Mino5,Reference van den Brink, Hendriks, Blanken, Koeter, van Zwieten and van Ree13–Reference Strang, Metrebian, Lintzeris, Potts, Carnwath and Mayet17

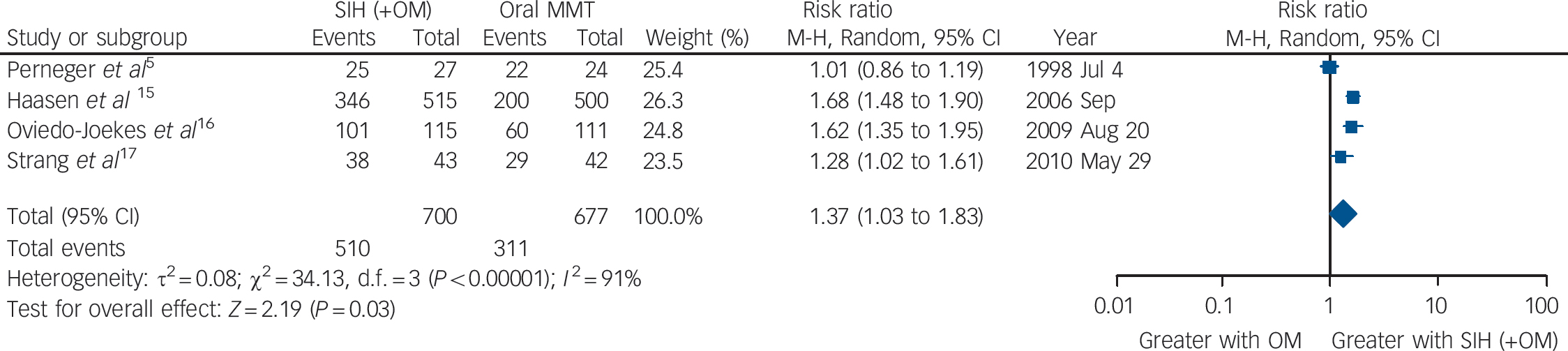

Retention in treatment outcome data

Utilising available data from four studies, Reference Perneger, Giner, del and Mino5,Reference Haasen, Verthein, Degkwitz, Berger, Krausz and Naber15,Reference Oviedo-Joekes, Brissette, Marsh, Lauzon, Guh and Anis16,Reference Strang, Metrebian, Lintzeris, Potts, Carnwath and Mayet17 our meta-analysis identified a significant advantage of SIH over oral MMT treatment in retention in treatment: overall RR = 1.37 (95% CI 1.03–1.83), heterogeneity (P<0.00001), I 2 = 91% (Fig. 2). The Dutch Reference van den Brink, Hendriks, Blanken, Koeter, van Zwieten and van Ree13 and the Spanish Reference March, Oviedo-Joekes, Perea-Milla and Carrasco14 studies were excluded from the analysis of retention because of the specific construction of the two study conditions, i.e. as per trial designs, the participants in the MMT groups had an automatic right to be offered SIH at the end of the randomised trial period. The possibility of exclusion of the RIOTT for the same reason was considered; however, this was not required as there was no automatic right to be offered injectable maintenance at the end of the 6-month randomised trial period, even though there was, in practice, a sympathetic consideration of this request if it was made.

Fig. 2 Supervised injectable heroin (SIH) + flexible doses of oral methadone v. oral methadone: retention in treatment.

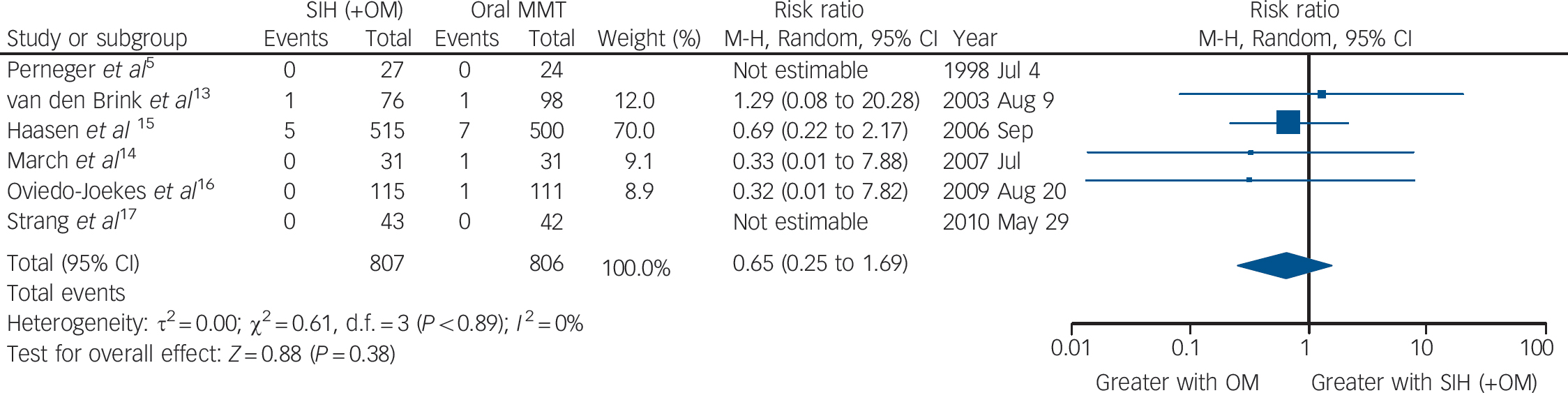

Mortality outcome data

The six trials collectively identified 16 events of death (SIH: n = 6; oral MMT: n = 10) resulting in a numerical advantage of SIH over oral MMT, but crossing the mid-line: RR = 0.65 (95% CI 0.25–1.69), heterogeneity (P = 0.89), I = 0% (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Supervised injectable heroin (SIH) + flexible doses of oral methadone v. oral methadone: mortality.

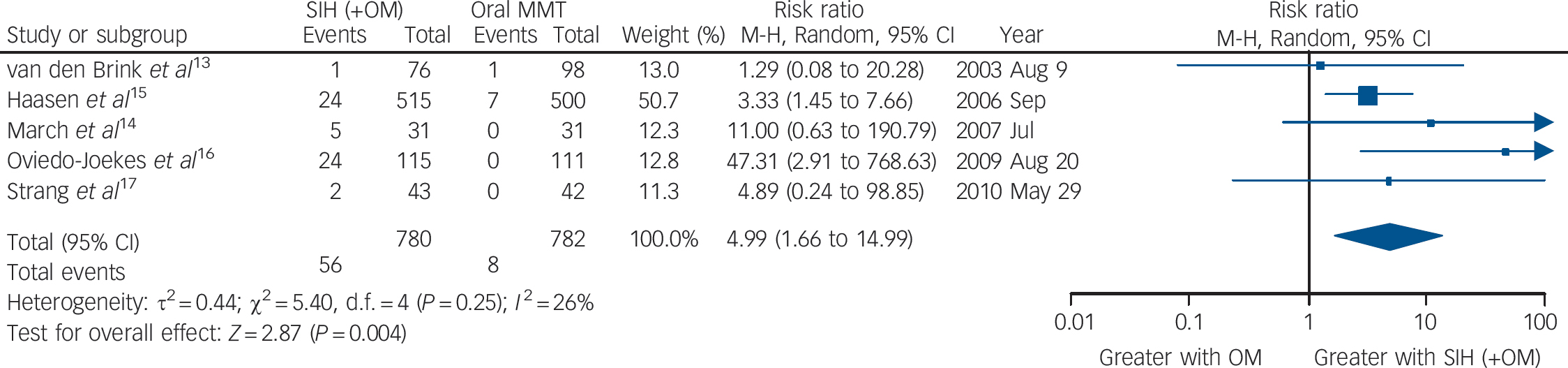

Side-effects data

Taking all side-effects together (serious adverse events probably or definitely related to study medication), the five trials (the Swiss study did not report side-effects data) showed a significant higher risk of side-effects in the SIH compared with the oral MMT treatment groups: RR = 4.99 (95% CI 1.66–14.99), heterogeneity (P = 0.25), I 2 = 26% (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Supervised injectable heroin (SIH) + flexible doses of oral methadone v. oral methadone maintenance treatment (MMT): side-effects (serious adverse events probably/definitely related to study medication).

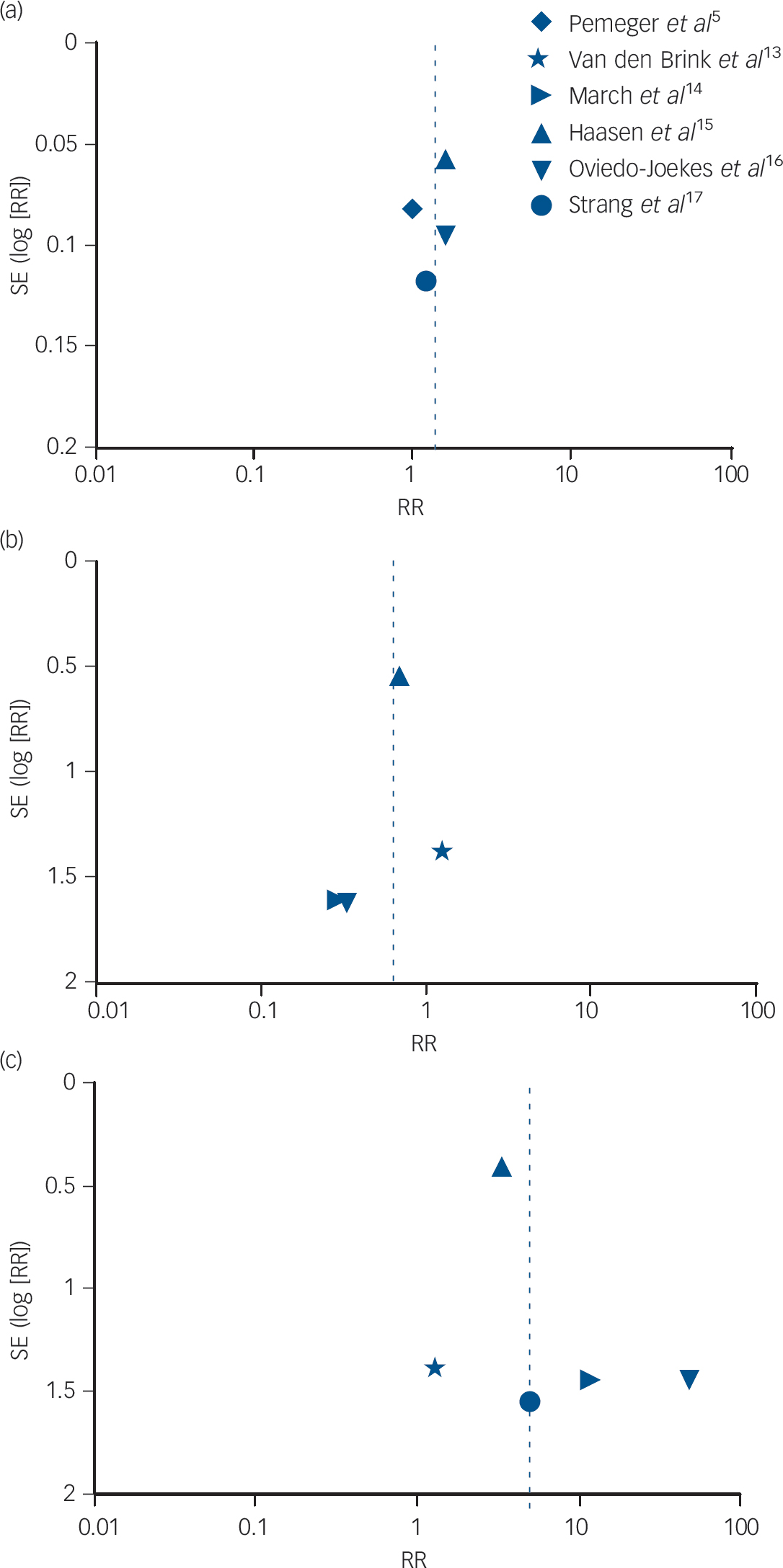

Publication bias

Figure 5 presents the funnel plots to assess potential publication bias for the meta-analyses. We have restricted this to a visual inspection of the plots in line with recommendations not to perform statistical tests of asymmetry where there are a small number of trials. Reference Sterne and Harbord49 The first two funnel plots (Fig. 5a and 5b) relate to the outcomes of retention (as reported earlier and in Fig. 2) and of mortality (as reported earlier and in Fig. 3), and they indicate that the studies had, respectively, very small and small standard errors and RR estimates spanning from below 1 to approximately 2. However, with the outcome of side-effects, the funnel plot in Fig. 5c indicates that the studies included much more variable standard error estimates, with RR above 10, which may reflect small sample size or other limitations.

Fig. 5 Funnel plot of comparison: supervised injectable heroin (SIH) + flexible doses of oral methadone v. oral methadone – outcomes: (a) retention in treatment; (b) mortality; and (c) side-effects.

National and international impact on clinical practice and policy

At the international level, the 1961 and 1971 UN conventions 50,51 contain no explicit regulations concerning the prescribing of diamorphine (heroin) in the context of substitution treatment provision, leaving it to the competence of national governments to regulate in this area. National legislation differs greatly between countries. With the exception of the UK, the development of regulation by means of law and guidelines around heroin prescribing for opioid treatment is a very recent matter.

(a) Countries in which diamorphine exists as a medicinal product

(i) Full approval of diamorphine as a medicinal product (UK). The medical use of heroin is, and always has been, recognised in the UK as a legitimate medicine which a doctor may prescribe for the relief of pain and suffering, as well as for the treatment of opioid dependence. 52,53 However, since the late 1960s, the authority to prescribe diamorphine for addiction treatment has been restricted to doctors with a special licence (essentially being addiction specialists), while all medical practitioners continue to have the authority to prescribe diamorphine for other conditions (e.g. severe pain relief, acute management of coronary infarction).

(ii) Approval of diamorphine as a medicinal product for the specific indication of treatment-refractory heroin dependence (Switzerland, Germany, The Netherlands and Denmark). In Switzerland, Germany and The Netherlands, heroin has been given approved medication status as a legitimate (albeit reserved for severe cases) opioid substitution treatment. In 2001, injectable heroin was registered in Switzerland as a medication for maintenance treatment in opioid dependence, followed by its inclusion on the list of provisions to be fully paid by health insurance in 2002; and, finally, a legal basis was obtained through revision of the narcotic law in 2008. 54 A similar process has been followed and completed over the last decade in The Netherlands Reference van den Brink, Hendriks, Blanken, Koeter, van Zwieten and van Ree13 and in Germany. Reference Pfeiffer-Gerschel, Kipke, Floter, Lieb and Raiser55 In Denmark in 2008, amendment to the Controlled Substances Act was adopted, which allowed the provision of supervised heroin-prescribing and its integration into the existing therapeutic network as an additional treatment for long-term heroin addicts. 56

(b) Countries which have approved diamorphine for research trials

There are also other countries where, in recent years, approval has been given for diamorphine to be prescribed within the context of a randomised trial (e.g. Canada and Spain) – for example, through approval by the Office of Controlled Substances of Health Canada and a Section 56 exemption from Canada's Narcotics Control Act Reference Gartry, Oviedo-Joekes, Laliberte and Schechter57 and, in Spain, through Royal Decrees 75/1990 58 and 5/1996. 59 Approval was granted in 2007 for a similar trial in Belgium that was recently finalised (no report available yet).

(c) Countries in which diamorphine is totally prohibited and hence not available as a medicinal product nor as a research medication

Finally, there are all other countries in the rest of the world where either (i) such treatment appears never to have been seriously proposed or (ii) heroin-prescribing trials have been proposed but have then either been blocked or approval has not been granted (Australia, USA and France).

Discussion

Main findings

A total of six randomised trials from six countries have been included in this review. Based on the evidence that has been accumulated through these clinical trials, heroin-prescribing, as a part of highly regulated regimen, is a feasible and effective treatment for a particularly difficult-to-treat group of heroin-dependent patients. Diamorphine hydrochloride (pharmaceutical heroin) is now registered as a medicinal product for this indication in five European countries (Switzerland, The Netherlands, Germany, UK and Denmark). New research is now testing whether further improvements could be achieved with combination of SIH and incentive reinforcement (termed contingency management, CM) or other specific rehabilitation strategies. Following the conduct of this series of rigorous randomised trials, several countries have altered research restrictions and there has also been new regulatory approval and politically supported changes in narcotics laws of these countries, so that this potentially effective treatment is now becoming available for at least some of the patients whose addiction was previously considered untreatable (and still is, in most countries). An additional option has been added to the clinical algorithm, which can improve personalisation of individually relevant treatment provision, to the benefit of individuals as well as society at large.

Comparison with Cochrane

It is appropriate to compare and contrast the conclusions from the above analyses with the conclusions from earlier and more recent Cochrane Reviews. Reference Ferri, Davoli and Perucci12,Reference Ferri, Davoli and Perucci60 The original 2005 Cochrane Review Reference Ferri, Davoli and Perucci60 examined studies published up to 2002 (and with only two of the studies included in our analysis above) and concluded that, even though there were some results in favour of heroin treatment, ‘no definitive conclusions about the overall effectiveness of heroin prescription (was) possible’. By the time of the later Cochrane Review in 2011, all six of the above-randomised trials were included in the new Cochrane analysis, Reference Ferri, Davoli and Perucci12 and the Cochrane group concluded that, on the basis of the expanded current evidence, ‘heroin prescription should be indicated to people who (are) currently or have previously failed maintenance treatment, and it should be provided in clinical settings where proper follow-up is ensured’, while also noting that adverse events were consistently more frequent in the heroin groups.

However, a major difference exists in the approach taken by our analyses v. the main approach taken by the Cochrane Review: the Cochrane group have included all trials of heroin prescribing, regardless of whether the administration was supervised or for take-home administration (although with additional analyses later included along the lines of the above analyses), whereas we have regarded the SIH approach as a distinct treatment necessitating its own specific scrutiny and analysis. We consider this distinction important because we wish to avoid any possible contamination of analyses, which could result from inclusion of findings from earlier trials in which supplies of heroin were given to addicts on a take-home basis. We thus consider it more appropriate to analyse solely the trials of the new clinical approach of SIH, and this is the basis of our analyses above. The overall conclusions are similar, but a clearer and stronger signal emerges from the more specific narrower approach we have taken.

Obstacles to fuller impact

The introduction of effective interventions, even when demonstrably effective, can sometimes, at first, be viewed as controversial. SIH treatment is often viewed thus. A number of concerns have been raised and we address these in turn.

(a) Concerns about the adequacy of the scientific evidence

This was previously a major obstacle, but has now largely been addressed by the series of trials described above. All of the trials have broadly shown similar benefits and in the same direction – with regard to ‘street’ heroin and other drug use as well as in secondary outcome domains such as physical, mental health and social functioning where these have been studied (Spain, Reference Perea-Milla, Aycaguer, Cerda, Saiz, Rivas-Ruiz and Danet38 Germany Reference Vogel, Knopfli, Schmid, Prica, Strasser and Prieto22,Reference Eiroa-Orosa Haasen, Verthein, Dilg, Schafer and Reimer28,Reference Haasen, Verthein, Eiroa-Orosa Schafer and Reimer29,Reference Karow, Reimer, Schafer, Krausz, Haasen and Verthein30,Reference Scafer, Eiroa-Oroa, Verthein, Dilg, Haasen and Reimer36,Reference Miller, Forzisi, Lintzeris, Zador, Metrebian and Strang41 and Canada Reference Oviedo-Joekes, Guh, Brissette, Marchand, Marsh and Chettiar34,Reference Oviedo-Joekes, Guh, Marsh, Brissette, Nosyk and Krausz35 ). Also, the latest 2011 Cochrane review Reference Ferri, Davoli and Perucci12 reaches a more positive conclusion on SIH than the original 2005 Cochrane review. Reference Ferri, Davoli and Perucci60 However, scientific questions still remain. The new empirical evidence from randomised trials on heroin treatment has mostly focused on short-term outcome, with the randomisation phase of treatment being a maximum of 12 months. Nevertheless, longer-term data are also available from eight extended follow-up studies in four countries (Switzerland, Reference Rehm, Gschwend, Steffen, Gutzwiller, Dobler-Mikola and Uchtenhagen8,Reference Rehm, Frick, Hartwig, Gutzwiller and Uchtenhagen45,56 The Netherlands, Reference Blanken, Hendriks, van Ree and van den Brink26 Spain Reference Oviedo-Joekes, March, Romero and Perea-Milla33 and Germany Reference Verthein, Schafer and Degkwitz21,Reference Verthein, Haasen and Reimer25,Reference Verthein, Bonorden-Kleij, Degkwitz, Dilg, Kohler and Passie42 ) with a consistent finding of additional sustained benefit across a range of different outcome categories. We also need to learn more about the process and influences on remission of illicit drug use and elimination of related problems, and, more importantly, enhanced quality of life and social functioning of these patients.

(b) Concerns about security, public safety, and potential for diversion and abuse

Much concern has been expressed over security, public safety and potential for diversion of prescribed heroin. Three of the randomised trials have evaluated the impact of newly established injectable clinics on crime in trial localities: The Netherlands, Reference Blanken, van den Brink, Hendriks, Huijsman, Klous and Rook27 Canada Reference Lasnier, Brochu, Boyd and Fischer31 and the UK. Reference Miller, McKenzie, Lintzeris, Martin and Strang32 Findings to date suggest no negative effects of the new supervised injecting clinics on public safety, and actual reports of growing local public support.

(c) Concern about rebound damage to other treatments such as oral MMT and rehabilitation

Concern that prescribed diamorphine would preferentially attract heroin users and would undermine other treatments has not been borne out. Most of the six trials actually experienced difficulty in recruiting participants, either failing to reach target recruitment Reference March, Oviedo-Joekes, Perea-Milla and Carrasco14,Reference Oviedo-Joekes, Brissette, Marsh, Lauzon, Guh and Anis16,Reference Strang, Metrebian, Lintzeris, Potts, Carnwath and Mayet17 or needing to extend the planned recruitment time. Reference Haasen, Verthein, Degkwitz, Berger, Krausz and Naber15,Reference Strang, Metrebian, Lintzeris, Potts, Carnwath and Mayet17 It appears that for many marginalised heroin users, the attraction of prescribed diamorphine is rarely sufficient to promote engagement in highly structured treatment. Recent documented experience Reference Groshkova, Metrebian, Hallam, Charles, Martin and Forzisi20,Reference Marchand, Oviedo-Joekes, Guh, Brissette, Marsh and Schechter24,Reference Blanken, van den Brink, Hendriks, Huijsman, Klous and Rook27,Reference Romo, Poo and Ballesta40,Reference Miller, Forzisi, Lintzeris, Zador, Metrebian and Strang41,Reference Clark61,Reference Hannah62 suggests that many patients attending the new injecting clinics aim at sobriety in the longer term or return to healthier stability in existing MMT programmes. However, this still needs to be studied further. A suitable response to the needs and aspirations of this patient group will involve investment of collective effort to developing recovery-oriented heroin maintenance – an approach that will combine heroin pharmacotherapy and a sustained menu of recovery support services to assist patients and families in achieving long-term addiction recovery.

(d) Financial costs

In a context of ever-increasing health costs and competing health priorities, heroin prescribing might be difficult for governments to embrace. Findings of international research Reference Byford, Barrett, Metrebian, Groshkova, Cary and Charles19,Reference Nosyk, Guh, Bansback, Oviedo-Joekes, Brissette and Marsh23,Reference Haasen37,Reference Dijkgraaf, van der Zanden, de Borgie, Blanken, van Ree and van den Brink44 have consistently demonstrated a considerable economic benefit of SIH because of the reduction in the costs of criminal procedures, imprisonment and healthcare. Different models of possible service provision of heroin treatment may identify variants of SIH treatment which are more affordable, and this was being explored in England Reference Strang, Groshkova and Metrebian63,64 up until 2015 when the central funding for this new treatment was not renewed

(e) Hijack by campaigning groups

The encouraging findings from the randomised trials has been picked up by groups campaigning for major changes in the law and the trials have been described as if they were trials of legalisation (which they were not). These misrepresentations are not only misleading but also risk damaging the robustness of the conclusions and the integrity of the clinical procedures. This difficulty is not unique to the heroin trials, and it similarly interferes with objective discussion of harm reduction policies and practices; Reference MacCoun and Reuter65–Reference Strang67 however, careful attention to accurate secondary reporting of the findings of the heroin trials is important so that they are properly understood and the potential for advancement properly identified.

(f) Diamorphophobia

A critical concern relates to public and political anxiety about the acceptability of the idea of heroin being a medicinal product. While diamorphine has existed as a pharmaceutically manufactured medicinal product in the UK for more than a century, the situation is very different in most other countries where heroin is usually regarded as always an illicitly manufactured drug of abuse and addiction. This has contributed to an inability to establish clinical research trials (e.g. Australia Reference Bammer68 ) and to the refusal to provide continuity of diamorphine treatment for individuals beyond the end of trial treatment (e.g. Spain). It is possible that the Canadian identification of similar benefits with injectable hydromorphone Reference Byford, Barrett, Metrebian, Groshkova, Cary and Charles19 may point to an avenue which might circumvent more severe expressions of such diamorphophobia.

(g) Safety

Several of the trials have reported instances of sudden-onset respiratory depression in people receiving injectable diamorphine, at a rate of about 1 in every 6000 injections, Reference Oviedo-Joekes, Brissette, Marsh, Lauzon, Guh and Anis16,Reference Strang, Metrebian, Lintzeris, Potts, Carnwath and Mayet17 hence well below the hazard from injecting street heroin but nevertheless producing clinically critical events. These have all been safely managed with resuscitation measures, but, as noted in the 2011 Cochrane review, this necessitates specific attention and emphasises the importance of supervision of injection by appropriately trained staff. Reference Dursteler-Macfarland, Stohler, Moldovanyi, Rey, Basdekis and Gschwend43 This repeated finding warrants fuller study, and future research will clarify whether it relates to the medicinal product (diamorphine/heroin) itself or to some other aspect of drug-taking behaviour or drug treatment provision. Some such work is ongoing.

Next steps

A trial of SIH treatment has been conducted (2011–2013) in Belgium and future versions of the analysis will be likely to include data from this trial also, once the findings from this further trial have been peer-reviewed and published.

Limitations

The key limitation of this review is that the analysis synthesised the interpretation of the primary data in each paper rather than considering the primary data directly. Future research could compare SIH treatment outcomes across these trials for a number of outcomes by analysing individual patient data generated by the different research groups.

Funding

Funding was received from the EMCDDA (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction) to support review of the international randomised trials of supervised injectable diamorphine (heroin) prescribing and the preparation of a 2012 European report on the evidence-base for this approach for the treatment of entrenched heroin addiction and associated evolving practice.

Acknowledgements

We thank Marina Davoli, Marica Ferri and the Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group for their contribution. J.S. is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.