Clinical practice guidelines, national strategy plans (such as the French Alzheimer plan), the World Alzheimer Reports, and many scientific and non-scientific publications all stress the existence of various ethical issues in dementia care and the importance of awareness and capacity building in this area.Reference Post and Whitehouse1,2 A core challenge for the adequate development of reports, guidelines and training programmes that address ethical issues in dementia care is an unbiased and comprehensive account of all (discussed/reported) ethical issues at stake. Such an unbiased and comprehensive set of ethical issues (a full spectrum of ethical issues) in dementia care can be based on a systematic literature review. This review serves several purposes. First, it raises awareness of the variety of ethical issues and the complexity of ethical conduct in dementia care. Second, together with a comprehensive list of the underlying publications, it can be used to build the basis for the systematic development of information and training materials for health professionals, relatives, patients or society as a whole. Finally, it can be used as the basis for a rational and fair selection of all those ethical issues that should be addressed (with more or less priority) in health policy decision-making and national or local dementia strategies, position papers or clinical practice guidelines.

There are several recent books, reports and review papers intended to highlight (implicitly or explicitly) the range of ethical issues in dementia care.Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3-Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6 To date, the British Nuffield Council on Bioethics report Dementia: Ethical Issues is probably the most extensive.2 Its development involved a working group of 14 experts (mostly from the UK), public consultations, fact-finding meetings and peer review. However, the report, as well as most other existing overviews, could be classified as a narrative (non-systematic) review that did not employ explicit measures to prevent bias and to guarantee comprehensiveness in identifying and presenting relevant literature. Also, the Nuffield Council report is, understandably, oriented specially to the situation in the UK. Furthermore, because of their narrative approach, the mentioned reviews are not structured in a way that clearly illustrates the full spectrum of ethical issues in dementia care. To our knowledge there is only one review of all ethical issues in dementia that employed a systematic review methodology.Reference Baldwin, Hughes, Hope, Jacoby and Ziebland7 This review focused on the older literature published between 1980 and 2000 and presented ethical issues in only one small-scale table listing 20 broad categories (for example advance directives, decision-making or feeding issues) and some examples of subcategories (such as living wills, euthanasia, genetics). This review did not include any further explanation of ethical issues in dementia care, nor link the set of ethical issues to the retrieved references. Another systematic review focused more specifically on empirical literature studying ethical issues in dementia from the perspective of non-professional carers.Reference Hughes, Hope, Savulescu and Ziebland8

The purpose of our review was to determine the full spectrum of ethical issues in clinical dementia care based on a systematic review of the recent literature published between 2001 and 2011 (including journal articles, reports and books). We define a ‘full spectrum of disease-specific ethical issues (DSEIs)’ as a structured, qualitative account of ethical issues in the context of a specific disease (such as dementia), divided into broad categories and narrow subcategories that are based on text examples from the original literature that was included in the review. The purpose of our review is purely descriptive ('empirical' in its literal meaning). A description of the full spectrum of DSEIs prepares the ground for the planning and development of clinical guidelines, national and local dementia strategies and curricula for teaching and capacity-building activities. The aim of our review, therefore, was not to make judgements on the practical relevance or value of specific ethical issues. Moreover, this review does not present any normative recommendations on how to deal with every single ethical issue detected. In the discussion section, however, we highlight core methodological steps that should be taken into account when drafting normative recommendations on the basis of the results of the review.

Method

Literature search and eligibility criteria

We searched in Medline using the following search algorithm: (((((”Ethics”[Mesh])) OR (”ethics”[ti])) OR (”ethical”[ti])) AND (((((”Dementia”[Mesh])) OR (”Dementia”[ti])) OR (”Alzheimer's Disease”[ti])) OR (”Alzheimer Disease”[ti])). The search was restricted to English and German language literature and to publications from 1 January 2000 to 31 January 2011. We searched in Google books with the search string “Dementia AND ethics”. Because of the vast number of hits (12 200) and because Google books listed ‘most relevant’ hits at the top of the list, we focused on the first 100. The ordering for relevance had face validity as we found, among these first 100 hits, many textbooks and monographs that dealt with dementia and ethics we were aware of. No search restrictions were used for the Google books search. The Discussion explains and justifies why we restricted our literature search to Medline and Google books.

For the definition of DSEI we referred to the ethical theory of principlismReference Beauchamp and Childress9 that forms the basis of many ethical and medical professionalism frameworks.10,11 Principlism is based on the four principles of beneficence, non-maleficence, respect for autonomy and justice. These principles represent prima facie binding moral norms that must be followed unless they conflict, in a particular case, with an equal or greater obligation. Moreover, they provide only general ethical orientations that require further detail to give guidance in concrete cases. Thus, when being applied, the principles have to be specified and - if they conflict - balanced against one another. With respect to the principlism approach, a DSEI might arise (a) because of the inadequate consideration of one or more (specified) ethical principles (for example: insufficient consideration of patient preferences in dementia care decisions) or (b) because of conflicts between two or more (specified) ethical principles (for example, balancing the benefits, harms and the respect of patient autonomy in decision-making for or against physical restraints on account of inappropriate patient behaviour).

We included a publication only if: (a) it described a DSEI in clinical dementia care, and (b) the DSEI can be dealt with by individual caregivers or care institutions and does not depend on preceding health policy or political decision-making (for example campaigns for reducing the stigma of dementia, political decisions about the limitations of voting by people with dementia), and (c) it does not relate only to ethical issues in research on dementia (research ethics), and (d) the publication was a peer-reviewed article, a scientific book (for example textbooks or monographs) or a national-level report.

Extraction and categorisation of DSEIs

Our aim was to develop a qualitative framework of narrow and broad categories of DSEIs (the full spectrum of DSEIs) that best accommodated the DSEI mentioned in the included publications. We identified and compared paragraphs that mentioned DSEIs across papers. We matched discussion of DSEIs from one paper with DSEIs from another. We then built first-order (broad) and second-order (narrow) categories for DSEIs that captured similar DSEIs mentioned in different papers.

Paragraphs from the retrieved literature were extracted that described situations that explicitly or implicitly relate to our definition of DSEI. Extraction and categorising of DSEIs unavoidably involves interpretative tasks (for example which text passages deal with a DSEI? What is the appropriate broad and narrow category for the DSEI?). To uphold the validity of coding as well as intercoder reliability we employed the following procedure. Three authors (D.S., M.M. and M.S.) identified and initially categorised DSEIs independently in a subsample of five publications that all could be classified as narrative reviews.Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3-Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Walaszek12 The authors discussed whether paragraphs mentioned a DSEI and how they should be categorised. The remaining 87 publications were grouped in three clusters of 47, 20 and 20 publications. All publications that at initial inspection appeared to be more detailed and comprehensive were purposively put together in the first cluster of 47 publications. One author (M.S.), with a PhD in philosophy, then extracted and categorised DSEIs from this first cluster. The result was a first version of the DSEI spectrum. The second and third clusters were then used to check theoretical saturation of the DSEI spectrum. Theoretical saturation implies that no new categories can be generated.Reference Strauss and Corbin13 The other authors (D.S., M.M., G.N. and H.K.) with professional backgrounds in clinical psychiatry, clinical ethics consultation, philosophy and health services research checked the extraction and categorisation of DSEI in a random sample of 18 publications. Coding problems were resolved by frequent meetings and discussions with all authors. Because the aim of our review was not to assess how often a certain DSEI was mentioned in the literature we only extracted two paragraphs with similar content for each DSEI. We extracted more than two paragraphs per DSEI only in those cases where the content allowed further specification of a certain DSEI.

Results

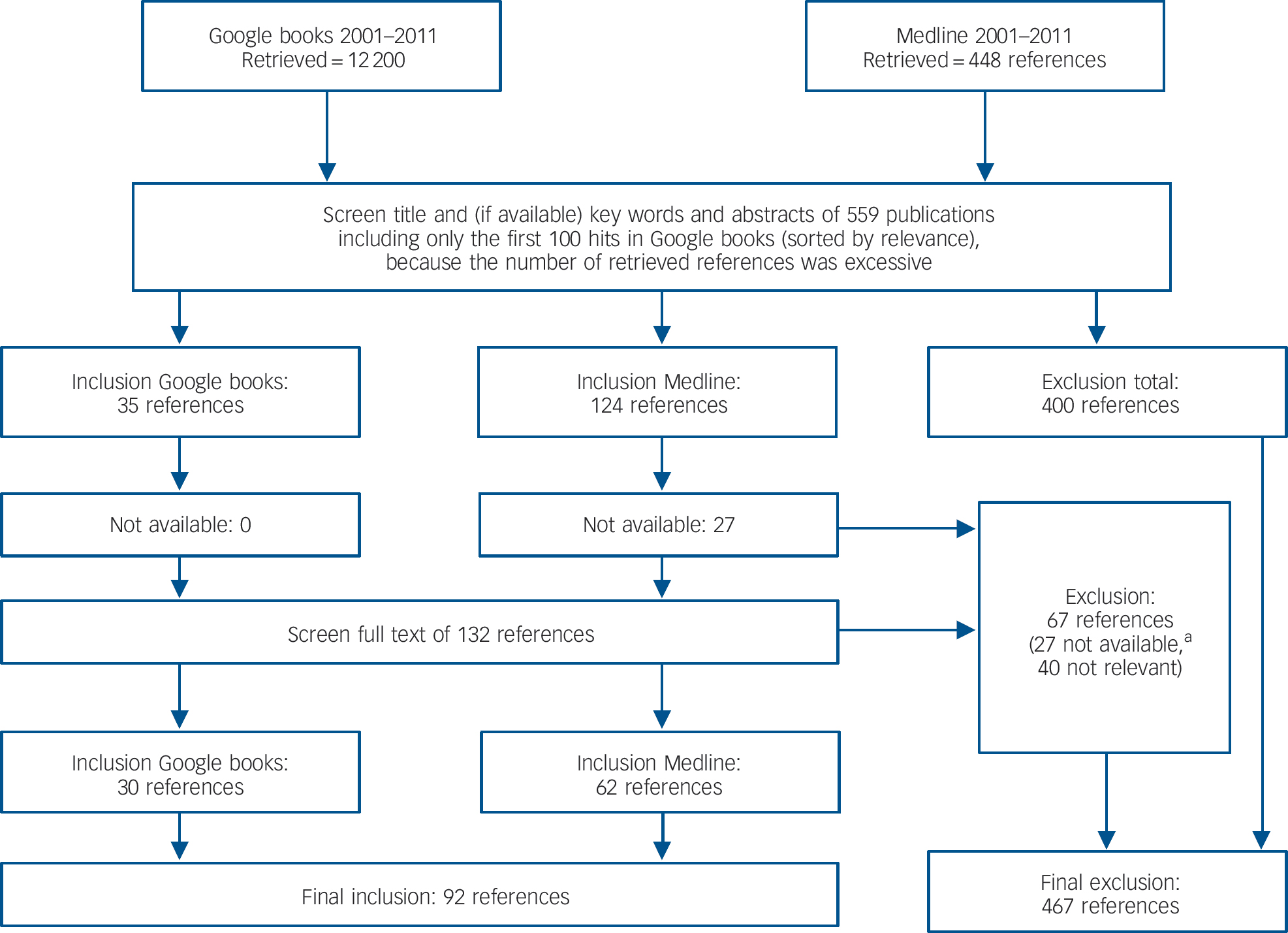

Our literature search retrieved 559 references of which 92 were finally included in the review (Fig. 1). More than half (47, 51%) were published between January 2008 and February 2011. Two-thirds were peer-reviewed journal articles (62, 67%) published in 42 different journals including all relevant disciplines (Table 1). Other publication sources were for example book chapters, monographs or reports. Most journal articles and all but one book were written in English (78, 85%).

The 92 publications together included a spectrum of 56 DSEIs that were grouped under seven major categories: diagnosis and indication; patient decision-making competence; disclosure and patient information; decision-making and informed consent; social and context-related aspects; professional conduct and evaluation; and specific care situations (see Appendix). For each major category, DSEIs were further specified in first- and second-order DSEI categories (Appendix). For example, the major category ‘Diagnosis and medical indication’ consists of 12 second-order DSEIs grouped under 4 first-order DSEIs. An example of a first-order DSEI is ‘Adequate point of making a diagnosis’. This DSEI consists of three second-order DSEIs, of which one is ‘Risk of disavowing signs of illness and disregarding advance planning’. A text example (among others) that built the basis for this DSEI is the following: ‘But there is also the opposite risk that out of a laudable wish to preserve a person's freedom and to avoid giving false label to an existential problem, signs of illness are missed and the ill old person is denied necessary and effective treatment’.Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3 We found text passages in other references that allowed further specification of this second-order DSEI. We cite these references in the Appendix, but for didactic and readability purposes we did not further specify third- and fourth-order DSEIs in this paper. Our analysis received theoretical saturation for the first- and second-order DSEI categories after analysing the third cluster of retrieved references (see Method). Online Table DS1 presents one or two text examples for each of the 56 DSEIs. We therefore have not repeated the presentation of DSEI categories and the underlying text examples in the results section.

Fig. 1 Flow chart for inclusion/exclusion of references.

a. A reference was classified as being ‘not available’ in cases where we did not have access to the paper and where the authors did not respond when we asked them to supply a copy.

The first six main categories involve DSEIs that deal with specific steps in the circular processes of medical decision-making (diagnosis, patient information, treatment/care decisions, evaluation of decisions, etc.) that are characteristic of the management of all diseases but are considered with respect only to dementia in this paper. The seventh major category involves DSEIs that deal with specific situations in the management of dementia that in principle involve all steps of the decision-making process (for example dealing with tube feeding, restraints or suicidality).

Table 1 Characteristics of included publications

| References, n (journals, n) | |

|---|---|

| Publication type | |

| Journal articles | 62 |

| Book chapters | 20 |

| Books/reports | 10 |

| Language | |

| English | 78 |

| German | 14 |

| Field of journal | |

| Medicine/gerontology/palliative care | 22 (14) |

| Ethics/philosophy | 22 (11) |

| Psychiatry/neurology/psychology | 11 (11) |

| Nursing/caring | 6 (5) |

| Social science | 1 (1) |

| Total | 62 (42) |

Discussion

Dementia care in all its interactions and care situations is deeply intertwined with ethical issues. Dealing with ethical issues in a systematic and transparent manner requires, first of all, an unbiased awareness of the spectrum and complexity of DSEIs. Second, it seems important for didactic and pragmatic purposes to fit this spectrum of DSEIs to everyday care situations and to the stepwise processes of medical decision-making rather than to more abstract philosophical categories or ethical principles.

In this paper we presented the full spectrum of DSEIs in dementia care as they are described in the available scientific literature (including medical and nursing journals, organised public consultations and surveys). Our review covers all DSEIs for dementia care that were presented in the already mentioned systematic review of the older literature published between 1980 and 2000.Reference Baldwin, Hughes, Hope, Jacoby and Ziebland7 In addition, our review revealed further DSEIs, further specified DSEIs and directly linked the DSEIs to the relevant references. The findings of this comprehensive and detailed review can raise the awareness that general ethical principles such as ‘respect of patient autonomy’ or ‘beneficence’ obviously need specification (see Appendix) to inform medical decision-making in all its different steps (for example information about the patient, assessing patient decision-making competence, evaluating former decisions and current practice).

Categorisation of DSEIs

This review is the first one that demonstrates what the categorisation and reporting of DSEIs can look like. Further evaluation is needed to assess the advantages and disadvantages of this structured and detailed reporting on DSEIs, in comparison with other more general and abstract types of reportingReference Baldwin, Hughes, Hope, Jacoby and Ziebland7 or narrative book-length descriptions.2,Reference Hughes and Baldwin14 However, the detailed categorisation of DSEIs as the main finding of this review highlights a core challenge in applying systematic review methodology to the field of bioethics: the critical appraisal of systematic reviews of ethics literature should not only address the quality of the literature search but also, with equal importance, the validity and usefulness of the synthesis of findings. Thus, in this review, the full spectrum of DSEIs is presented in first- and second-order categories.

This DSEI spectrum can serve various purposes. It can be used as training material for healthcare professionals, students and the public, to raise awareness and improve understanding of the complexity of ethical issues in dementia care. It can also be used for the systematic and transparent identification of ethical issues that should be addressed in dementia-specific training programmes, national strategy plans and clinical practice guidelines.

We recommend employing the methods applied in this review for the systematic identification of DSEIs in other cognitive and somatic diseases. Although different first- and second-order categories are to be expected for ethical issues in other diseases we assume that the overarching structure of our DSEI spectrum is applicable to all diseases, namely six major categories that deal with the stepwise processes of medical decision-making and one additional major category dealing with specific care situations. Whereas the literature on DSEIs in dementia care was extensive, and therefore allowed theoretical saturation of the respective DSEI spectrum, systematic reviews of DSEIs in other diseases might retrieve fewer references that address DSEIs. To reach theoretical saturation of the respective DSEI spectrum in these cases the systematic literature review might need to be complemented by expert input on DSEIs or surveys of healthcare professionals, patients and relatives. Further research is needed on how these complementary DSEI sources can be integrated in an equally systematic and transparent manner.

Limitations

One limitation of this first systematic review of DSEIs might be seen in the fact that we restricted our search to Medline and Google books. It is clear to us that although our review was systematic we did not include ‘all’ the existing literature dealing with ethical issues in dementia care. We restricted our search to the above-mentioned databases for four main reasons: first, and most important, we reached theoretical saturation for the first- and second-order categories of DSEIs after assessing the 92 references retrieved for Medline and Google books. We did not aim to reach theoretical saturation for the third-order categories. Second, former systematic reviews in the field of bioethics demonstrated the broad coverage of ethics literature in Medline and the little additional value of searching medical ethics literature in other databases such as EMBASE, CINAHL or Euroethics.Reference Sofaer and Strech15,Reference Strech, Persad, Marckmann and Danis16 Third, the characteristics of publications included in this systematic review (Table 1) demonstrate that the 92 references covered journals from all relevant fields. Fourth, the 92 references included several narrative reviews,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Hughes, Baldwin, Jacoby, Oppenheimer and Dening17 topic-specific monographsReference Hughes and Baldwin14,Reference Wetzstein18 and comprehensive reports such as the Nuffield Council on Bioethics report on dementia.2 Currently, the field of systematic reviews on ethical issues (or argument-based literature in general) lacks broadly consented standards such as those available for systematic reviews on clinical research, for example Moher et al.Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman19 Further conceptual and empirical research should address the question on how to modify systematic review methodology for its reasonable application in the field of bioethics.Reference Strech and Sofaer20-Reference McCullough, Coverdale and Chervenak23

We stress the fact that a systematic and transparent process in identifying ethical issues does not automatically indicate that further steps in dealing with such a spectrum are systematic, too. Further research is needed to evaluate how health policy decision-makers or guideline-development panels can chose the ‘most important or pressing’ DSEI from the full spectrum in a transparent and participative manner. The purpose of this review was not to quantify how often certain DSEIs have been mentioned in the literature. It is questionable whether such frequency data are helpful. It might, however, be important to know whether a certain DSEI is more or less frequent in ordinary dementia care. However, such frequency data cannot be derived by counting how often a certain DSEI has been mentioned in the literature. Survey research among carers and patients, informed by the findings of this review, would be a better tool for gaining these frequency data. Further challenges in interpreting quantitative characteristics of systematic reviews in bioethics are described elsewhere.Reference Strech and Sofaer20

Ethical decision-making in dementia care

It should be stated that the process of drafting recommendations on how to deal with individual DSEIs faces several methodological challenges.Reference Eriksson, Hoglund and Helgesson24 On the one hand, oversimplification needs to be avoided to guarantee meaningful and helpful content. The Nuffield Council report provides a good example of how some of the complex DSEIs captured in our DSEI spectrum can be addressed by providing a set of criteria that do not indicate a one-size-fits-all solution for ethical challenges but rather guide the process of ethical decision-making in dementia care. A good example is the second-order DSEI ‘Problems concerning understanding and handling of patient autonomy’. The Nuffield Council addresses this DSEI as follows: ‘Wellbeing factors, such as the person's general level of happiness are also important but again cannot automatically take precedence over the person's interests in having their autonomy respected’.2 In the following, the Nuffield Council suggests factors that should be taken into account when weighing up the conflicting ethical principles in dementia care (well-being v. respect of autonomy):

‘(i) How important is the issue at stake?, (ii) How much distress or pleasure is it causing now?, (iii) Have the underlying values or beliefs on which the earlier preferences were based genuinely changed or can they be interpreted in a new light?, (iv) Do the apparent changes in preferences or values result from psychosocial factors (such as fear) or directly from the dementia (such as sexually disinhibited behaviour), or are they linked with a genuine pleasure in doing things differently?’2

Future developments of dementia-care-specific clinical guidelines, information material and national strategy plans can use the findings of this review for the identification and prioritisation of key ethical issues in dementia care. In addition, transparent procedures should be applied for drafting and approving recommendations that guide everyday ethical decision-making in dementia care.

Appendix

The spectrum of disease-specific ethical issues (DSEIs) in dementia care

1 Diagnosis and medical indication

Adequate consideration of complexity of diagnosing dementia:

• Risk of making a diagnosis too early or too late because of reasons related to differences in age- or gender-related disease frequenciesReference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Schmidt25

• Risk of making inappropriate diagnoses related to varying definitions of mild cognitive impairment2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Walaszek12,Reference Hughes, Baldwin, Jacoby, Oppenheimer and Dening17,Reference Murray and Boyd26-Reference Füsgen30

• Underestimation of the relatives' experiences and assessments of the person with dementia2,Reference Füsgen30,Reference Steeman, de Casterlé, Godderis and Grypdonck31

Adequate point of making a diagnosis:

• Risk of disavowing signs of illness and disregarding advanced planningReference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Walaszek12,Reference Steeman, de Casterlé, Godderis and Grypdonck31,Reference Kruse32

• Respecting psychological burdens in breaking bad newsReference Hughes, Baldwin, Jacoby, Oppenheimer and Dening17,Reference Füsgen30,Reference Steeman, de Casterlé, Godderis and Grypdonck31,Reference Carpenter and Dave33

• Underestimation of the relatives' experiences and assessments of the person with dementia2,Reference Füsgen30,Reference Steeman, de Casterlé, Godderis and Grypdonck31

Reasonableness of treatment indications:

• Overestimation of the effects of current pharmaceutical treatment optionsReference Graham and Ritchie27,Reference Synofzik34

• Considering challenges in balancing benefits and harms (side-effects)2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Synofzik34-Reference Schwaber and Carmeli36

• Not considering information from the patient's relatives2,Reference Rai, Eccles and Rai5,Reference Wetzstein18,Reference Oliver, Gee and Rai37

Adequate appreciation of the patient:

• Insufficient consideration of the patient as a person2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Hughes and Baldwin14,Reference Murray and Boyd26,Reference Füsgen30,Reference Steeman, de Casterlé, Godderis and Grypdonck31,Reference Post, Hughes, Louw and Sabat38-Reference Mahon and Sorrell40

• Insufficient consideration of existing preferences of the patient2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Hughes and Baldwin14,Reference Hughes, Baldwin, Jacoby, Oppenheimer and Dening17,Reference Steeman, de Casterlé, Godderis and Grypdonck31,Reference Synofzik34,Reference Briggs, Vernon and Rai35,Reference Mahon and Sorrell40-Reference Weissenberger-Leduc50

• Problems concerning understanding and handling of patient autonomy2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Walaszek12,Reference Mahon and Sorrell40,Reference Boyle51,Reference Dworkin, Green and Bloch52

2 Assessing patient decision-making competence

Ambiguity in understanding competence2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Walaszek12,Reference Hughes and Baldwin14,Reference Hughes, Baldwin, Jacoby, Oppenheimer and Dening17,Reference Dworkin, Green and Bloch52-Reference Welie and Widdershoven57

Problematic aspects in patient decision-making competence:

• Inadequate assessment2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Rabins and Black4,Reference Hughes and Baldwin14,Reference Helmchen and Lauter29,Reference Welie and Widdershoven57,Reference Chernoff58

• Inadequate consideration of setting or decision content2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Rabins and Black4,Reference Walaszek12,Reference Cornett and Hall59

• Disregarding the complexity of assessing authenticity2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Hughes and Baldwin14,Reference Holm55,Reference Vollmann60,Reference Hartmann, Förstl and Kurz61

• Underestimation of the relatives' experiences and assessments of the patient2,Reference Füsgen30

3 Information and disclosure

• Respecting patient autonomy in the context of disclosure2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Walaszek12,Reference Briggs, Vernon and Rai35,Reference Defanti, Tiezzi, Gasparini, Congedo, Tiraboschi and Tarquini53,Reference Welie and Widdershoven57,Reference Cornett and Hall59,Reference Schermer62

• Adequate amount and manner of information2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Hughes and Baldwin14,Reference Steeman, de Casterlé, Godderis and Grypdonck31,Reference Carpenter and Dave33,Reference Briggs, Vernon and Rai35,Reference Cornett and Hall59,Reference Schermer62

• Adequate involvement of relatives2,Reference Rabins and Black4,Reference Carpenter and Dave33,Reference Cornett and Hall59

• Consideration of cultural aspects2,Reference Rabins and Black4

4 Decision-making and consent

Improvement of patient decision-making competence:

• Risk of inadequate involvement of the patient in the decision-making processReference Rai, Eccles and Rai5,Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Menne and Whitlatch49,Reference Defanti, Tiezzi, Gasparini, Congedo, Tiraboschi and Tarquini53

• Risk of insufficient conditions for fostering decision-making capacity2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Walaszek12,Reference Hofmann63

• Risk of disregarding the need of continuous relationship building with the patient as a means to foster patient autonomy2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Defanti, Tiezzi, Gasparini, Congedo, Tiraboschi and Tarquini53

• Risk of setting the time for decision-making processes too short2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3

• Risk of weakening patient decision-making competence by infantilisation2,Reference Steeman, de Casterlé, Godderis and Grypdonck31

Responsible surrogate decision-making:

• Adequate handling of ‘best interest’ and ‘substituted judgements’ decisions2-Reference Rabins and Black4,Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Walaszek12,Reference Hughes and Baldwin14,Reference Hughes, Baldwin, Jacoby, Oppenheimer and Dening17,Reference Briggs, Vernon and Rai35,Reference Mahon and Sorrell40,Reference Boyle51,Reference Dworkin, Green and Bloch52,Reference Holm55,Reference Dworkin64-Reference Gedge71

• Inadequate communication with relatives2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Hughes and Baldwin14,Reference Murray and Boyd26,Reference Oliver, Gee and Rai37,Reference Penrod, Yu, Kolanowski, Fick, Loeb and Hupcey39,Reference Goldsteen, Widdershoven, McMillan and Hope72-Reference Synofzik78

• Inadequate handling of information stemming from relatives2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Oliver, Gee and Rai37,Reference Defanti, Tiezzi, Gasparini, Congedo, Tiraboschi and Tarquini53,Reference Barnes and Brannelly73,Reference Nagao, Aulisio, Nukaga, Fujita, Kosugi and Youngner79

• Need of advanced planning2-Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Walaszek12,Reference Baumrucker, Davis, Paganini, Morris, Stolick and Sheldon48,Reference Kwok, Twinn and Yan75

• Risk of disregarding legal clarifications2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6

Adequate consideration of living wills/advance directives:

• Challenges in interpreting the living will/advance directiveReference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Hughes, Sabat, Widdershoven, McMillan and Hope41,Reference Defanti, Tiezzi, Gasparini, Congedo, Tiraboschi and Tarquini53,Reference Vollmann60,Reference Maio66,Reference Gastmans and Denier70,Reference Schermer80

• Challenges in deciding to follow or not to follow the content of the living will/advance directive2,Reference Rabins and Black4,Reference Hughes and Baldwin14,Reference Briggs, Vernon and Rai35,Reference Defanti, Tiezzi, Gasparini, Congedo, Tiraboschi and Tarquini53,Reference Maio66,Reference Harvey67,Reference Gastmans and Denier70

5 Social and context-dependent aspects

• Caring for relatives2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Rabins and Black4,Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Hughes and Baldwin14,Reference Wetzstein18,Reference Füsgen30,Reference Steeman, de Casterlé, Godderis and Grypdonck31,Reference Baldwin, Widdershoven, McMillan and Hope76,Reference Bolmsjo, Edberg and Sandman77,Reference Kastner and Löbach81-Reference Gatterer and Croy83

• Caring for clinical personnel and professional carers2,Reference Strauss and Corbin13,Reference Bolmsjo, Edberg and Sandman77,Reference Jakobsen and Sorlie84-Reference Yamamoto and Aso87

• Assessment of the patient's potential to do (direct or indirect) harm to othersReference Rabins and Black4,Reference Rai, Eccles and Rai5,Reference Schwaber and Carmeli36,Reference Robinson, O'Neill and Rai88

• Responsible handling of costs and allocation of limited resources2,Reference Oppenheimer, Bloch and Green3,Reference Rai, Eccles and Rai5,Reference Walaszek12,Reference Graham and Ritchie27,Reference Rosen, Bokde, Pearl and Yesavage89

6 Care process and process evaluation

• Continuing assessment of potential benefits and harms2,Reference Synofzik34-Reference Schwaber and Carmeli36,Reference Kalis, von Delden and Schermer90

Adequate patient empowerment:

• Patient-oriented setting2,Reference Rai, Eccles and Rai5,Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Füsgen30,Reference Oliver, Gee and Rai37,Reference Villars, Oustric, Andrieu, Baeyens, Bernabei and Brodaty91

• Motivation of patientsReference Füsgen30,Reference Steeman, de Casterlé, Godderis and Grypdonck31,Reference Kruse32,Reference Sabat92

Self-reflection of carers:

• Attitudes towards patients with dementia2,Reference Rai, Eccles and Rai5,Reference Kalis, von Delden and Schermer90

• Reflection on conflicts of interests and values2,Reference Rabins and Black4,Reference Rai, Eccles and Rai5,Reference Defanti, Tiezzi, Gasparini, Congedo, Tiraboschi and Tarquini53,Reference Morris, Jones and Miesen93,Reference Kalis, van Delden and Schermer94

• Continuing education/capacity building of the carers2,Reference Rabins and Black4,Reference Steeman, de Casterlé, Godderis and Grypdonck31,Reference Jakobsen and Sorlie84,Reference Hughes95,Reference Richter and Eisemann96

Evaluation of abuse and neglect2,Reference Rabins and Black4,Reference Walaszek12

7 Special situations for decision-making

Ability to driveReference Rabins and Black4-Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Walaszek12,Reference Robinson, O'Neill and Rai88,Reference Rapoport, Herrmann, Molnar, Man-Son-Hing, Marshall and Shulman97

Sexual relationships2,Reference Walaszek12

Indication for genetic testingReference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Walaszek12

Usage of GPS (global positioning system) and other monitoring techniques2,Reference Hughes and Baldwin14,Reference Landau, Auslander, Werner, Shoval and Heinek98-Reference Landau, Auslander, Werner, Shoval and Heinik100

Prescription of antibioticsReference Schwaber and Carmeli36,Reference Rozzini and Trabucchi68

Prescription of antipsychotic drugs2,Reference Walaszek12

Indication for brain imaging2,Reference Rosen, Bokde, Pearl and Yesavage89

Covert medicationReference Hughes and Baldwin14,Reference Hokanen101,Reference Lamnari102

Restraints2,Reference Rai, Eccles and Rai5,Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Hughes, Baldwin, Jacoby, Oppenheimer and Dening17,Reference Defanti, Tiezzi, Gasparini, Congedo, Tiraboschi and Tarquini53,Reference Yamamoto and Aso87,Reference Rosen, Bokde, Pearl and Yesavage89,Reference Sayers, Rai and Rai103,Reference Weiner and Tabak104

Tube feeding2,Reference Rabins and Black4-Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6,Reference Walaszek12,Reference Hughes and Baldwin14,Reference Gove, Sparr, Dos Santos Bernardo, Cosgrave, Jansen and Martensson46,Reference Chernoff58,Reference Geppert, Andrews and Druyan69,Reference Synofzik78,Reference Briggs, Vernon and Rai105-Reference Werner107

End of life/palliative care2,Reference Bernat, Duyckaerts and Litvan6

SuicidalityReference Rabins44,Reference Hartmann, Förstl and Kurz61

Funding

This work was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) (Project number: STR 1070/2-1).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Julian Hughes, Georg Marckmann and Reuben Thomas for critical feedback on an earlier version of this paper.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.