The use of coercion is common in formal and non-formal settings,Reference Ssengooba1,2 including mental health services.Reference Sashidharan, Mezzina and Puras3 Coercive treatment comprises a broad range of practices, ranging from implicit or explicit pressure to accept certain treatment to the use of forced practices such as involuntary admission, seclusion and different forms of restraint.Reference Gooding, McSherry and Roper4 Available epidemiological data suggest wide variations in the rates of involuntary admissions across countries, local areas and services,Reference Weich, McBride, Twigg, Duncan, Keown and Crepaz-Keay5 with rates increasing over time in some countries.Reference de Stefano and Ducci6 In England, for example, the rate of involuntary psychiatric hospital admission has increased by more than one-third in the past 6 years, and in Scotland the number of detentions has increased by 19% in the past 5 years.Reference Sashidharan and Saraceno7 In The Netherlands, in the period 2003–2017 the rate of treated requests for court-ordered involuntary admissions increased from 44 to 64 per 100 000 population.Reference Broer, Wierdsma and Mulder8,Reference Broer, Mooij, Quak and Mulder9 Involuntarily admitted people may also be exposed to further coercive measures during hospital admissions, such as seclusion, administration of medication against their will and restraint, but the frequency and severity of these multiple forms of coercion are still poorly understood.Reference Ssengooba1–Reference Gooding, McSherry and Roper4

Coercive treatment conflicts with the principle of autonomy, a central guiding principle of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which aims to empower mental health patients in making their own decisions about treatment.Reference Freeman, Kolappa, de Almeida, Kleinman, Makhashvili and Phakathi10,Reference Sugiura, Mahomed, Saxena and Patel11 In addition to human rights considerations, empirical data suggest that coercive practices may be a traumatising experience leading to profound loss of trust in the therapeutic relationship and to physical health problems such as skin injuries, neurological problems, pulmonary disease, deep vein thrombosis and even death.Reference Hammervold, Norvoll, Aas and Sagvaag12,Reference Franke, Busselmann, Streb and Dudeck13 Coercion can also have long-term adverse consequences in terms of service avoidance, with reduced access to mental healthcare.Reference Lasalvia, Zoppei, Van, Bonetto, Cristofalo and Wahlbeck14

Against this background, during recent decades strategies and interventions have been developed to reduce the use of coercion, simultaneously attempting to preserve the right of people with mental health conditions to receive effective treatments, including when they may be less able to express their own will and preferences.Reference Gooding, McSherry and Roper4,Reference Puras and Gooding15 However, the efficacy of these interventions is controversial, and the evidence fragmented into several reviews focusing on different populations, interventions and outcomes, leading some to conclude that there is very little research in this area.Reference Sashidharan, Mezzina and Puras3 Consequently, most evidence-based guidelines for mental health conditions do not consider measures to reduce coercion.

Therefore, the aim of this umbrella review was to summarise the efficacy of interventions to reduce the use of coercive care in mental health services. Effect sizes for interventions were re-analysed using quantitative umbrella review criteria in order to accurately quantify the strength of associations, and credibility of evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.16–Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Akl, Kunz, Vist and Brozek18

Method

Study design

We employed an umbrella review methodology to systematically review all available reviews on the topic. Umbrella review is a term applied to systematic overviews of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.Reference Ioannidis19–Reference Barbui, Purgato, Abdulmalik, Acarturk, Eaton and Gastaldon22 This review methodology was chosen as it provides an overall picture of an important area of healthcare and it can highlight whether the evidence base is consistent or contradictory.Reference Solmi, Correll, Carvalho and Ioannidis23 In clinical areas with multiple interventions for the same condition, or with multiple populations for similar interventions, and with several clinically relevant outcomes, umbrella reviews may provide quantitative syntheses of the beneficial effects of interventions for different populations and outcomes using a common metric.Reference Papatheodorou21–Reference Solmi, Correll, Carvalho and Ioannidis23 A review protocol was registered in the Open Science Framework platform: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/S76T3.

Types of systematic review included

Systematic reviews of randomised studies investigating the efficacy of interventions to reduce coercive treatment for people with mental health conditions in any treatment setting were included. Interventions included any type of non-pharmacological strategies aiming to reduce the use of coercive measures such as involuntary admissions or use of physical restraint. Mental health conditions included any mental health problem along a continuum from mild, time-limited psychological distress to long-term and severely disabling conditions.Reference Patel, Saxena, Lund, Thornicroft, Baingana and Bolton24

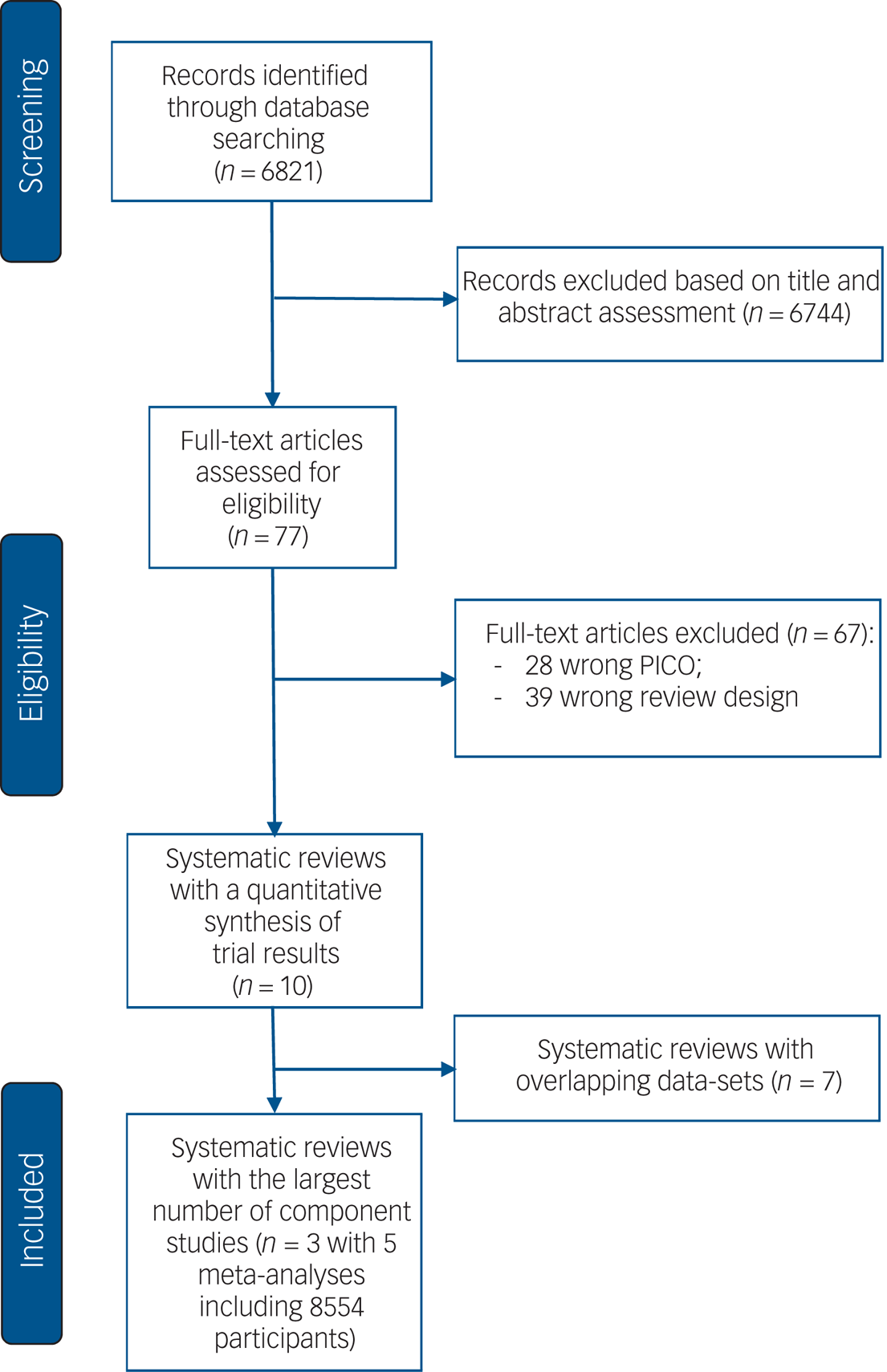

Only systematic reviews with a quantitative synthesis of trial results (meta-analysis) were retained. Similarly, systematic reviews without study-level effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were excluded. When two systematic reviews presented overlapping data-sets, the one with the largest number of component studies providing study-level effect sizes was retained for the main analysis, in agreement with umbrella review methodology.Reference Ioannidis19,Reference Barbui, Purgato, Abdulmalik, Acarturk, Eaton and Gastaldon22 References of primary studies from all identified meta-analyses were inspected to cross-check whether relevant primary studies were missed by the included systematic reviews.

Literature search, systematic review selection and data extraction

MEDLINE, PubMed, Cochrane Central, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Epistemonikos and Campbell Collaboration databases were searched from January 2010 to January 2020. The following terms were used: (coercio*[Title/Abstract] OR involunt*[Title/Abstract] OR restraint*[Title/Abstract] OR seclusion*[Title/Abstract] OR compulsory*[Title/Abstract]) AND (meta-analysis[Publication Type] OR meta-analysis[Title/Abstract] OR meta-analysis[MeSH Terms] OR systematic[Title/Abstract] OR review[Title/Abstract]). The complete search strategy is provided in the supplementary material, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.144. The search was restricted to the past 10 years to provide an up-to-date overview of the evidence.Reference Barbui, Purgato, Abdulmalik, Acarturk, Eaton and Gastaldon22 No language restrictions were applied. Electronic database searches were supplemented by a manual search of reference lists from relevant studies. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses reporting standards (PRISMA) were followed to document the process of systematic review selection.Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman25

The selection of potentially relevant systematic reviews was made by carefully inspecting titles and abstracts. This was done by two reviewers independently (C.B., M.P.). In case of discrepancies, a third review author (G.O.) was involved and consensus reached by discussion. When titles and abstracts did not provide information on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the full articles were obtained to verify eligibility. The full texts of potentially included systematic reviews were obtained and carefully appraised by at least two reviewers. The reference lists of included articles were analysed for additional items not retrieved by the database searches.

From each included systematic review, two investigators (C.B., M.P.) independently extracted information on first author, year of publication, outcomes, number of included studies and reported summary meta-analytic estimates. The following information was extracted from each primary study: year of publication, mental health condition, type of intervention, outcomes, sample size and study-specific effect size with the corresponding 95% confidence interval.

Reporting quality of included systematic reviews

The quality of included systematic reviews was independently assessed by two reviewers (C.B., M.P.) using AMSTAR 2 (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews), a 16-point assessment tool of the methodological quality of systematic reviews.Reference Shea, Reeves, Wells, Thuku, Hamel and Moran26 AMSTAR 2 has good interrater agreement, test–retest reliability and content validity (supplementary material).Reference Shea, Reeves, Wells, Thuku, Hamel and Moran26

Statistical analysis

Summary relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals were re-estimated using common metrics and random-effects models because we were expecting heterogeneity.Reference DerSimonian and Laird27 To produce a pragmatic measure of the efficacy of interventions, numbers needed to treat (NNTs) were calculated using the formulae provided by Furukawa.Reference Furukawa28 We also estimated the 95% prediction interval (PI) for the summary random-effects estimates.Reference Higgins, Thompson and Spiegelhalter29 Prediction intervals further account for heterogeneity between studies and specify the uncertainty for the effect that would be expected in a new study examining that same research question.Reference Higgins, Thompson and Spiegelhalter29 Heterogeneity was evaluated with Cochran's Q statisticReference Cochran30 (statistically significant for P < 0.10) and quantified with the I 2 metric.Reference Higgins and Green31 Egger's test was used to evaluate potential publication and small-study effects biases.Reference Sterne, Sutton, Ioannidis, Terrin, Jones and Lau32,Reference Egger, Davey, Schneider and Minder33 In particular, P ≤ 0.10 in the regression asymmetry test with a more conservative effect in the largest study was considered evidence for small-study effects bias.

We further evaluated the excess significance, which is a test that examines whether the observed number of studies (O) with statistically significant results (positive studies, P < 0.05) in each meta-analysis is larger than their expected number (E).Reference Ioannidis and Trikalinos34 For each meta-analysis, E was calculated as the sum of the statistical power estimates for each study in the meta-analysis. The power of each study was calculated by an algorithm using a non-central t-distribution.Reference Lubin and Gail35 The estimated power depends on the plausible effect size. As the true effect size for any meta-analysis is unknown, we assumed that the most plausible effect is given by the largest study. Excess significance for each meta-analysis was claimed at the P ≤ 0.10 level.Reference Ioannidis and Trikalinos34

On the basis of these calculations, we classified the strength of each association as ‘convincing’, ‘highly suggestive’, ‘suggestive’ or ‘weak’ (supplementary material).Reference Papatheodorou21,Reference Barbui, Purgato, Abdulmalik, Acarturk, Eaton and Gastaldon22,Reference Dragioti, Karathanos, Gerdle and Evangelou36,Reference Machado, Veronese, Sanches, Stubbs, Koyanagi and Thompson37 Specifically, meta-analyses were free from biases (convincing, class I) if they met the following criteria: P < 10−6 based on random effects meta-analysis; >1000 participants; low or moderate between-study heterogeneity (I 2 < 50%); 95% PI that excluded the null value; no evidence of small-study effects and excess significance; largest study nominally significant (P < 0.05). Highly suggestive association (class II) criteria required >1000 participants, highly significant summary associations (P < 10−6 by random-effects models) and largest study nominally significant (P < 0.05). Suggestive evidence (class III) criteria required only >1000 participants and P ≤ 0.001 by random-effects models. Weak association (class IV) criteria required only P ≤ 0.05. Associations were considered non-significant if P was >0.05. Statistical analyses and power calculations were performed using Stata version 15.0 for Windows (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). P-values were all two-tailed.

In addition to these quantitative criteria, the overall credibility of the estimates was qualitatively assessed by two reviewers (C.B., M.P.) using the GRADE method (supplementary material).Reference Barbui, Dua, van Ommeren, Yasamy, Fleischmann and Clark17,Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Akl, Kunz, Vist and Brozek18,Reference Guyatt, Juniper, Walter, Griffith and Goldstein38,Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Kunz, Vist, Falck-Ytter and Schunemann39 GRADE allows the credibility of estimate for each outcome to be rated and supplies a tabular overview of findings easily understandable for intervention participants, policy makers, research planners, guideline developers and other interested stakeholders.Reference Barbui, Dua, van Ommeren, Yasamy, Fleischmann and Clark17 Summary of findings tables were developed using GRADEPro GDT.

Results

Description of included systematic reviews

The systematic search yielded 6821 records. After duplicate removal and inspection of titles and abstracts, 77 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 67 were excluded for the reasons reported in the supplementary material, and 10 systematic reviews with a quantitative synthesis of trial results were identified and critically appraised with AMSTAR 2 (Fig. 1).Reference Ayalon, Lev, Green and Nevo40–Reference Stovell, Morrison, Panayiotou and Hutton49 From these ten systematic reviews we retained and included in statistical re-analysis the three non-overlapping systematic reviews with the largest number of component studies (Fig. 1 and supplementary material).Reference de Jong, Kamperman, Oorschot, Priebe, Bramer and van de Sande43,Reference Lan, Lu, Lan, Chen, Wu and Chang47,Reference Molyneaux, Turner, Candy, Landau, Johnson and Lloyd-Evans48 These 3 systematic reviews provided data on 5 meta-analyses, including 23 randomised studies, 24 comparisons and 8554 participants.Reference Henderson, Flood, Leese, Thornicroft, Sutherby and Szmukler50–Reference Testad, Mekki, Forland, Oye, Tveit and Jacobsen72

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow-diagram.

In terms of populations, four meta-analyses included participants with severe mental illness and one analysed studies with participants with cognitive decline or dementia (Table 1). In terms of interventions, four meta-analyses assessed the efficacy of the following interventions to reduce involuntary admissions: shared decision-making interventions (including advance statements, crisis cards and patient-held information strategies); community treatment orders; adherence-enhancement interventions; or integrated care interventions (Table 1). One meta-analysis assessed the efficacy of staff training to reduce use of physical restraint (Table 1). All studies were conducted in high-income countries.

Table 1 Main characteristics of the 23 primary studies included in the umbrella review

Quality assessment of the included systematic reviews

AMSTAR 2 was used to describe the methodological characteristics of the ten systematic reviews with a quantitative synthesis of trial results, including the three systematic reviews that contributed to the analysis (supplementary material). Two of the three included systematic reviews did not have a review protocol, and none of the three provided a list of excluded studies. In addition, the funding source of the primary studies was not reported (supplementary material). Otherwise, the three systematic reviews performed well in terms of quality of the search strategy, risk of bias, heterogeneity and publication bias assessment (supplementary material).

Summary effect sizes

Re-analysis of the five meta-analyses assessing the efficacy of interventions to reduce involuntary admissions and use of restraint is shown in Fig. 2, and the number of included studies and participants, as well as the main characteristics of each meta-analysis, are reported in Table 2. For the outcome of involuntary admissions, only the meta-analyses of the efficacy of shared decision-making interventions and integrated care reported a statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05) summary effect using random-effects models. Similarly, for the outcome of use of restraint, the meta-analysis on the efficacy of staff training interventions reported a statistically significant summary effect (P ≤ 0.05) (Table 2). Of these three meta-analyses, a significance threshold below 10−3 was reached by the meta-analyses of staff training interventions, but a significance threshold below 10−6 was not reached by any of the meta-analyses reporting a significant association (Table 2 and supplementary material). Similar NNT values were calculated for shared decision-making interventions (NNT = 17.60, 95% CI 10.21–63.70) and staff training (NNT = 16.26, 95% CI 11.68–26.75), while the NNT for integrated care was 10.95 (95% CI 5.30–70.63) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Efficacy of interventions to reduce coercive treatment. RR, risk ratio; NNT, number needed to treat.

Table 2 Characteristics, quantitative synthesis and umbrella review criteria of the five meta-analyses assessing the efficacy of interventions to reduce coercive treatment

RR, relative risk.

In all five meta-analyses, the 95% prediction intervals included the null value. Moderate to substantial heterogeneity (I 2 > 50%) was observed only in the meta-analyses on adherence therapy and staff training interventions. Risk of small-study effects bias was not observed in any of the five meta-analyses, but excess of significance bias was detected in the meta-analysis on integrated care (Table 2).

Umbrella review criteria and GRADE

On the basis of these calculations, the strength of association was categorised as weak for shared decision-making and integrated care interventions, and suggestive for staff training interventions. According to GRADE, the credibility of evidence was moderate for shared decision-making and staff training interventions, low for integrated care and community treatment orders and very low for adherence therapy (supplementary material).

Discussion

The present umbrella review included 8554 participants from 23 studies (24 comparisons) contributing to 5 meta-analyses assessing the efficacy of interventions to reduce involuntary admissions and use of restraint in mental health services. On the basis of umbrella review criteria and GRADE, the evidence on the efficacy of staff training to reduce use of restraint was supported by the most robust evidence, followed by the evidence on the efficacy of shared decision-making interventions and integrated care to reduce involuntary admissions in adults with severe mental illness. By contrast, community treatment orders and adherence therapy had no effect on involuntary admission rates. According to GRADE, the credibility of evidence for staff training and shared decision-making interventions was moderate, with numbers needed to treat suggesting clinically relevant effect, especially in view of the pragmatic and hard nature of the outcome measures.

The beneficial effect of these interventions should be considered against potential risks associated with their implementation. For example, a risk of not providing effective treatments when needed may occur as a consequence of respecting the principle of autonomy when patients are less able to express their own will and preferences.Reference Szmukler73 Reduction of involuntary admissions or use of restraint might lead to greater use of medicines, with a potential increase in negative patient outcomes,Reference Sacks and Walton74,Reference Zaami, Rinaldi, Bersani and Marinelli75 including a theoretical negative effect on stigma where there is no proper care of people with severe illness. Interestingly, the review of Molyneaux and colleagues, in addition to involuntary admissions, analysed the impact of shared decision-making interventions on voluntary admissions, which may be considered a proxy indicator of receiving care when needed.Reference Molyneaux, Turner, Candy, Landau, Johnson and Lloyd-Evans48 The finding that patients receiving shared decision-making interventions were admitted as often as the control group does not seem to give support to this potential risk, even though the provision of other forms of treatment, such as pharmacological or psychosocial interventions, has not been investigated.

Implications for implementation

Important implications for implementation can be drawn from these considerations. A first aspect is that these interventions have been developed to be used in the context of formal settings, that is in the context of existing mental health systems with a community-based organisation of mental healthcare.Reference Gooding, McSherry and Roper4 In addition to the many benefits of community-based and primary care and support, such services may reduce the need for hospital admission.Reference Sugiura, Mahomed, Saxena and Patel11,76 Another prerequisite is the presence of legislative measures and policies aiming at operationalising a rights-based approach to decision-making.Reference Sashidharan, Mezzina and Puras3,Reference Sugiura, Mahomed, Saxena and Patel11,Reference Hanna, Barbui, Dua, Lora, van Regteren and Saxena77,78 For these reasons, results may hardly be applied to contexts where detention, chaining and violent treatment occur outside any legislative framework.Reference Hanna, Barbui, Dua, Lora, van Regteren and Saxena77 In some countries, for example, human rights abuses have been documented in a diverse range of treatment settings, including state hospitals, rehabilitation centres and other types of formal facility.Reference Ssengooba1,2 Results may also hardly be applied to contexts where human rights abuses occur in non-formal settings such as spiritual healing centres and prayer camps.Reference Ssengooba1,2

A second aspect is that the lack of effectiveness of community treatment orders makes a radical rethinking of the use of this intervention essential, particularly as it is included in the legislation and policy of many countries, with the expectation that it would contribute to avoiding compulsory admissions to hospital and enhance engagement in the community.

Within a general legislative, policy and organisational framework, implementing specific interventions to reduce coercive treatment would probably require their inclusion in existing guidelines for mental health conditions. The present umbrella review provides the background evidence for such an inclusion. We found that the evidence base is still not optimal, especially in terms of strength of associations, but it is nevertheless suggestive that coercive treatment may be reduced without major shortcomings. The WHO mhGAP Intervention Guide, for example, recommends a number of communication skills to create an environment that facilitates communication and shared decision-making. It generally suggests the promotion of the rights of people with mental health conditions in line with international human rights standards, although specific interventions with the primary aim of reducing coercive treatment are not included.79 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline on psychosis (www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG178) does state that people have the right to be involved in discussions and to make informed decisions about their care, but this is reported as a general principle of care, and not as a structured group of interventions specifically developed to reduce involuntary admissions. Operationalised and specific recommendations are more likely to be followed. Similarly, the NICE guideline on bipolar disorder (www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG185) encourages people with bipolar disorder to develop advance statements while their condition is stable as part of information and support strategies, but there is no mention of this as part of strategies to reduce coercive treatment. Minimising the use of restraint is reported by the NICE guideline on dementia (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97), but how this should be achieved is not described. In this review we found suggestive evidence for a group of staff training interventions. It may also be important to link existing guidelines on the prevention and management of violence and aggression in mental healthcare80,Reference Steinert and Hirsch81 with guidelines for specific mental health conditions. This could allow harmonisation of recommendations, giving due consideration to specific interventions to reduce coercive treatment.

Limitations

A general limitation of this umbrella review is that the effect on coercive practices of legislation, policies, service organisation models and population-level interventions, such as interventions based on advocacy, awareness-raising campaigns, moral persuasion and public engagement, cannot be assessed by means of randomised trials, and therefore these factors were not included in the systematic reviews that met criteria for this study. Similarly, complex multicomponent actions that are considered active ingredients of community mental health services, such as ensuring comprehensive responsibility in all phases of treatment, working on the environment and the social fabric, and fostering service accountability toward the community,Reference Mezzina82 are difficult to evaluate in formal studies. However, absence of randomised evidence for these interventions does not mean that they are ineffective. Law 180 in Italy remains a paradigmatic example of the potential impact of legislative measures on coercive practices, as its implementation determined a progressive dramatic decrease in the rates of involuntary admissions over the subsequent 40 years.Reference Barbui, Papola and Saraceno83

Specific limitations of this umbrella review are those of the systematic reviews included, which, in turn, suffer from the limitations of the primary studies. The most frequently reported review shortcomings, detected by AMSTAR 2, were lack of a review protocol describing review methods prior to the conduct of the review, lack of information on funding and lack of a thorough discussion of between-study heterogeneity. Heterogeneity may be explained by differences in the details of the interventions, which may be considerable, and by the contexts in which the individual studies were conducted, which may vary greatly in terms of mental health laws, mental health and social care policies, resources and service configurations, and local social and cultural attitudes. Additional limitations refer to the umbrella review methodology, as this approach is based on statistical re-analysis of meta-analyses. By definition, therefore, umbrella reviews include only systematic reviews that applied a quantitative approach to data presentation, while systematic reviews providing qualitative descriptions of the included studies, without applying meta-analytic techniques, are excluded. Related to this, recently published primary studies might exist that have not been covered by the included meta-analyses. Another limitation is the narrow focus on involuntary admissions and use of restraint as main outcome measures. Although these are hard outcome measures, coercive treatment generally involves a broader range of implicit or explicit forms of pressure to accept certain treatments.Reference Gooding, McSherry and Roper4 The absence of studies from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where there is also widespread use of coercive treatment, is another important limitation of the existing literature.

Implications for research

In terms of implications for research, the present review suggests the need for further studies on shared decision-making interventions, aiming to increase the precision of the overall estimate and strength of association, in view of the finding that the largest study included in the analysisReference Thornicroft and Henderson84 highlighted a non-significant trend in favour of the intervention. Additionally, integrated care interventions, which included a crisis resolution team in one study, and a team providing cognitive–behavioural strategies and structured single-family psychoeducation in another, showed promising overall point estimates, but with wide confidence intervals, so the addition of new studies will probably substantially increase the strength and credibility of the evidence. We also note that studies on staff training interventions to prevent use of restraint were conducted in long-term facilities, nursing homes in most cases. A gap in knowledge therefore exists, as currently we do not know whether staff training may have similar beneficial effects on the use of restraint in acute in-patient psychiatric wards.Reference Allen, Fetzer, Siefken, Nadler-Moodie and Goodman85,Reference Bak, Brandt-Christensen, Christensen, Sestoft and Zoffmann86 We do have the first clinical trial, however, showing that training of traditional/faith healers, as well as a structured programme of collaboration with biomedical services, can dramatically reduce coercive practices in non-formal treatment settings.Reference Gureje, Appiah-Poku, Kola, Araya, Chisholm and Esan87

Further research is also needed on the potential impact of other interventions that may be particularly appropriate for reducing coercive treatment, such as peer-delivered mental healthcare,Reference Acri, Hooley, Richardson and Moaba88–Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Gleeson, Rice, Gonzalez-Blanch and Bendall91 domiciliary interventions,Reference Gomis, Palma and Farriols92 open dialogue approaches,Reference Lakeman93 online, social media and mobile technologies,Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Alcazar-Corcoles, Gonzalez-Blanch, Bendall, McGorry and Gleeson94 and the clubhouseReference Battin, Bouvet and Hatala95 and circle of care models.96 More generally, studies assessing the efficacy of interventions to reduce coercive treatment should always include clinical outcomes such as psychopathology status, use of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments, and use of voluntary admissions, in order to better describe whether the provision of these interventions is associated with decreased access to effective care. Future studies could benefit from more systematic mapping of contextual factors, as they may act as powerful effect modifiers. As frameworks for mapping of contextual variation across settings have been developed,Reference Pfadenhauer, Gerhardus, Mozygemba, Lysdahl, Booth and Hofmann97 their systematic use could allow future syntheses of what works, how and in what setting. Patient-rated and patient-generated outcome measures valued by patients should also be included. These studies should be conducted in formal and non-formal settings at different levels of economic development, including LMICs, so that legislative, policy, cultural and contextual factors can be taken into due consideration as potential determinants of intervention implementability and outcome.

Even though treatment guidelines may be extremely helpful in promoting the implementation of less coercive practices, we acknowledge that individual, stand-alone interventions may not be sufficient. To optimise uptake in clinical practice, a more general cultural change is probably needed.Reference Sashidharan, Mezzina and Puras3,Reference Sugiura, Mahomed, Saxena and Patel11 In particular, efforts should be dedicated to increasing participation in individual treatment choices, in policy and legislative decisions, and in general theoretical discussions, of a much broader range of stakeholders, including different groups of people with mental health conditions, family members, mental health professionals with clinical experience, scholars and experts in mental health legislation and policy.Reference Caldas de Almeida98 Finally, a profound reorientation in attitudes of professionals is necessary if practice is to change.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at http://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.144.

Data availability

All data included in this umbrella review were extracted from publicly available systematic reviews.

Author contributions

C.B. and M.P. designed the study. C.B. drafted the manuscript. M.P., M.N., G.O. and F.T. contributed to the database preparation and double check. C.B. and M.P. did data analyses. J.A., J.M.C.-d.-A., J.E., O.G., C.H,. B.S., S.S. and G.T. critically revised the manuscript. All authors commented on, revised and approved the draft and final manuscript.

Declaration of interest

C.B., M.P. and F.T. receive support from the European Commission, grant agreement number 779255 ‘RE-DEFINE: Refugee Emergency: DEFining and Implementing Novel Evidence-based psychosocial interventions’. G.T. is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) South London and by the NIHR Applied Research Centre (ARC) at King's College London NHS Foundation Trust and the NIHR Applied Research Unit. G.T. receives support from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01MH100470 (Cobalt study). G.T. is supported by the UK Medical Research Council in relation the Emilia (MR/S001255/1) and Indigo Partnership (MR/R023697/1) awards. C.H. receives support from AMARI as part of the DELTAS Africa Initiative (DEL-15-01). G.T. and C.H. are funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research Unit on Health System Strengthening in Sub-Saharan Africa, King's College London (GHRU 16/136/54) using UK aid from the UK government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at http://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.144.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.