Postnatal depression affects a mother's ability to cope with the care of her baby, and limits her capacity to engage positively with the baby in social interactions (Reference Murray, Cooper and HipwellMurray et al, 2003a ). Many studies report the detrimental effects of postnatal depression on the cognitive and emotional development of children (Reference Sharp, Hay and PawlbySharp et al, 1995; Reference Murray and CooperMurray & Cooper, 1996; Reference Murray, Sinclair and CooperMurray et al, 1999; Reference Hay, Pawlby and AngoldHay et al, 2003) and so it appears that this disorder has adverse consequences for two generations of individuals. Reported prevalence of postnatal depression varies from 10% to 22% (Reference O'Hara and SwainO'Hara & Swain, 1996; Reference Josefsson, Berg and NordinJosefsson et al, 2001; Reference Coates, Schaefer and AlexanderCoates et al, 2004), with about 70 000 women experiencing postnatal depression in the UK alone every year (Reference Glover, Onozawa and HodgkinsonGlover et al, 2002). Therefore, with its high prevalence and transgenerational effects, this disorder constitutes a highly significant public health problem.

Interventions designed to prevent postnatal depression in mothers have been disappointing (Reference Ogrodniczuk and PiperOgrodniczuk & Piper, 2003); Reference AustinAustin, 2004; Reference BrockingtonBrockington, 2004; Reference DennisDennis, 2005), whereas studies focusing on the early detection and treatment of postnatal depression have shown positive effects. However, these studies have concentrated on benefits to mothers (Reference Appleby, Warner and WhittonAppleby et al, 1997; Reference Misri, Kostaras and FoxMisri et al, 2000; Reference Cooper, Murray and WilsonCooper et al, 2003) and it is unclear whether these interventions benefit child behaviour or development. This cannot be assumed, because the relationship between maternal depression and adverse child behavioural outcomes may also be genetically mediated, and not just the result of a causal effect of maternal behaviour on child functioning (Reference Kim-Cohen, Moffitt and TaylorKim-Cohen et al, 2005). Nevertheless, the most recent Scottish guidelines published in 2002 (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2002) recommended that future research should assess the effects of interventions not just on mothers but also on the whole family unit. It is therefore important, for both research and clinical practice, to examine the effects of treating postnatal depression on the cognitive and psychosocial development of children. Therefore we sought to examine this issue within the context of a systematic review.

METHOD

Literature search

A systematic search was undertaken of 12 electronic bibliographic databases – MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, the Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Central Register of Controlled Trials and the American College of Physicians Journal Club), the Health Technology Assessment database, EBSCO, Zetoc, Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts, PsycINFO, the Social Sciences Citation Index, the British Nursing Index and the Allied and Complementary Medicine database – covering the period 1966 to 2005. Search words used in Medline were post partum depression, postnatal depression, maternal depression, puerperal disorder of melancholy, postpartum OR postnatal OR psychiatric disorders. These were combined with terms for trials and children such as Randomised controlled trial, controlled clinical trial, clinical trials, random allocation, double OR single blind methods, evaluation studies, cross over studies AND children, infant, toddler, baby, adolescents. No language restriction was applied. The Medline search strategy was modified for the search of other databases. Reference lists of all included articles and review articles were also checked to identify any other relevant studies. Owing to time constraints, ‘grey’ literature such as conference proceedings and unpublished data were not searched and authors reporting on maternal outcomes only were not contacted for queries on measurements of child outcomes.

Inclusion criteria

Studies that met the following criteria were selected: randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials; all types of treatment interventions (pharmacological and non-pharmacological) for mothers diagnosed with post-partum depression; and outcomes measured in children up to 14 years of age. Studies that measured outcomes in other siblings in the family were also included in the review.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they reported non-randomised interventions; interventions only for maternity ‘blues’ or maternal psychosis; or preventive interventions during the antenatal or early postnatal period, for participants identified to be at risk.

Assessment of studies

All identified abstracts were scanned by two reviewers independently. Each article that met the inclusion criteria was critically appraised, using a standard data extraction form, independently by two reviewers. Any queries about inclusion were discussed with the second reviewer and any disagreement was resolved by discussion with referral to a third reviewer. Information on study design, setting, sample characteristics, intervention details, measurement instruments used and follow-up was extracted. Child behaviour, mother–infant interaction or mother–infant relationship, and infant or child cognitive development (such as communicative, attentional and social skills) were the main outcomes assessed.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of each included study was also assessed using a standard quality assessment form adapted from the Cochrane Collaboration and the Jadad scale (Reference Jadad, Moore and CarrollJadad et al, 1996). Primary studies were assessed on the quality of random allocation of concealment; comparability of groups at baseline; masking of healthcare providers; outcome assessor's masking to intervention; time of follow-up, and percentage followed up; details of those leaving the trial; validation of the outcome measures used; reporting of outcomes (self-reported or objective measurement); and intention-to-treat analysis. Each of these criteria was graded from 0 to 2 according to the strength of compliance, giving a maximum total of 20. Each study was subsequently classified on the basis of the score obtained, with total scores below 10 considered to be weak, scores of 10–15 considered as moderate and scores above 15 as strong in quality.

Data analysis

Combination of results using meta-analysis was inappropriate owing to the heterogeneity of the included studies, which were varied in their interventions, outcome measurements and target populations. However, comparisons across studies were made, and direction of effect size discussed. The results are summarised according to the child outcome measures assessed.

RESULTS

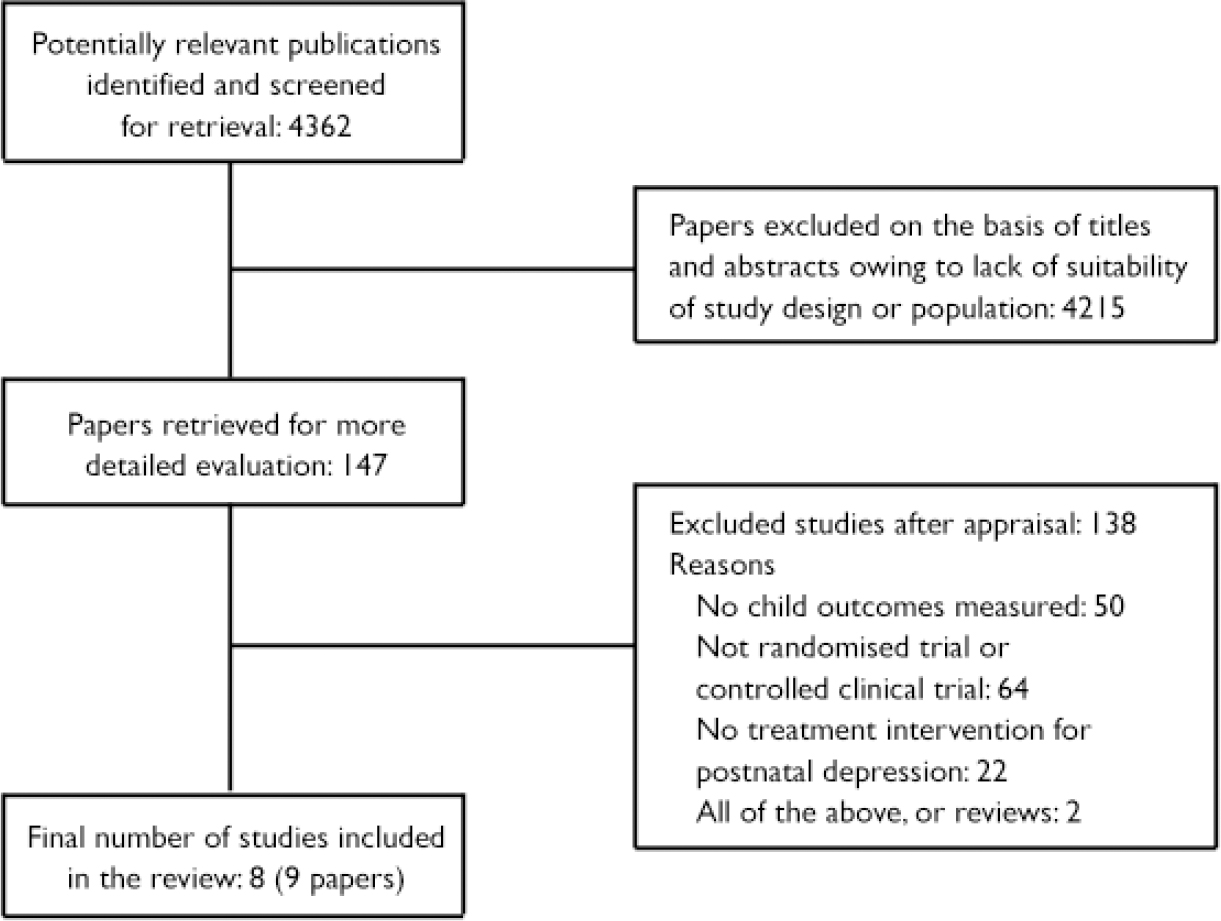

The search identified a total of 4362 abstracts, which were scanned and full texts of 147 potentially eligible articles were critically appraised. Eight randomised trials or controlled clinical trials (nine papers) that met the inclusion criteria assessing the effects of treatment of postnatal depression on child outcomes were included in this review. The selection process is summarised in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Selection process of the systematic review.

Of the eight studies identified, only three measured cognitive development in children (Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch and TothCicchetti et al, 2000; Reference Clark, Tluczek and WenzelClark et al, 2003; Reference Murray, Cooper and WilsonMurray et al, 2003b ) and the other five studies (six papers) assessed the effects of treatment on the mother–infant interaction or relationships (Reference Meager and MilgromMeager & Milgrom, 1996; Reference Hart, Field and NearingHart et al, 1998; Reference O'Hara, Stuart and GormanO'Hara et al, 2000; Reference Horowitz, Bell and TrybulskiHorowitz et al, 2001; Reference Onozawa, Glover and AdamsOnozawa et al, 2001; Reference Glover, Onozawa and HodgkinsonGlover et al, 2002). We considered that this was still an important outcome treatment measure, in that the quality of the early mother–infant relationship is likely to have important consequences for later emotional and behavioural development (Reference Murray, Sinclair and CooperMurray et al, 1999). Individual studies are presented according to the child outcomes measured.

Cognitive development in children

The three studies that assessed cognitive development in children (Table 1) were varied in their participants and the interventions. Murray et al (Reference Murray, Cooper and Wilson2003b ) had only mothers as participants, whereas the other two studies (Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch and TothCicchetti et al, 2000; Reference Clark, Tluczek and WenzelClark et al, 2003) included mothers and their infants. Cicchetti et al (Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch and Toth2000) investigated the efficacy of toddler parent psychotherapy (n=43) in postnatally depressed women, comparing them with 54 depressed mother–infant pairs not receiving this therapy 61 normal mother–infant pairs with no intervention (Table 1). The intervention lasted over a year (weekly for 57 weeks). The Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) were used at baseline and the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scales of Intelligence (WPPSI–R), which measure IQ in children aged 3–7 years, were used for older children. At the end of the trial, the WPPSI–R full-scale IQ score showed statistically significant differences between the groups (P=0.008). Whereas, the infants from the intervention group had IQ scores as high as those of the non-depressed control group (P=0.91), the infants in the control group with untreated depression had significantly lower full-scale IQ scores than either of the other two groups (nondepressed control group, P=0.009; intervention group, P=0.02). Further analysis demonstrated that these overall differences were attributed to group differences in the verbal performance IQ scales of the children (P=0.024; mean verbal IQ scores were 104.2 in the intervention group, 103.7 in the non-depressed control group and 97.5 in the depressed control group), with no statistically significant difference between the groups for performance IQ (P=0.10). Analyses of the differences between the standardised full-scale IQ and standardised Bayley Mental Development Index (MDI) score also revealed significant differences between groups (P=0.05). Following the same pattern, post hoc tests found that infants in the depressed control group were significantly less well developed than those in the other two groups, who did not differ from each other. Additional factors that could potentially account for the intervention effects were used as additional covariates in the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to examine cognitive functioning, controlling for the baseline MDI score. These factors included maternal education, subsequent depressive episodes, marital status, mother's work status and presence or absence of comorbidities. In this analysis only subsequent depressive episodes accounted for the cognitive outcome difference at 36 months, with significant differences for full-scale IQ scores (P=0.012) and verbal scores (P=0.015) but not for performance IQ scores. This followed the same pattern with worse outcomes for the depressed control group compared with the other two groups.

Table 1 Studies that assessed cognitive development in children

| Study | Location, design and quality of study | Details of participants | Intervention and delivery | Outcome measurements and results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cicchetti et al (Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch and Toth2000) | USA | Mothers and infants (n=187) | Toddler parent psychotherapy (n=43) compared with depressed (controls) (n=54) and non-depressed controls (n=61) | Primary outcome: child cognitive development, assessed by the Bayley Mental Development Index in infants and Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scales of Intelligence in older children |

| Design: RCT | Age: mothers, mean 31.6 years; infants, mean 20.5 months | Psychotherapy was delivered on a weekly basis for an average of 57 weeks between child ages 20 months and 3 years, mean number of sessions was 45 | Results: significant differences in favour of the psychotherapy group (n=43) compared with depressed controls (n=54) for cognitive development in children. No significant difference between the psychotherapy group and non-depressed controls (n=61) | |

| Quality of study: moderate | No follow-up | |||

| Murray et al (Reference Murray, Cooper and Wilson2003b ) | UK | Mothers only (n=193) | Routine primary care (n=52) compared with one of the three index interventions such as counselling (n=48), cognitive—behavioural therapy (n=43) and psychodynamic therapy (n=50) | Primary child outcomes: child behaviour, mother—infant relationship, infant attachment and child cognitive development, various tools were used to assess child outcomes at different time points |

| Design: RCT | Age: mothers, range 26-28 years; infants, mean 18 months | Therapy was conducted on a weekly basis, from 8 weeks to 18 weeks post-partum, by specialists in the three intervention fields; routine care was delivered by GPs and health visitors | Results: all the treatments showed some short-term benefit in mother—infant relationship and child outcomes with counselling and cognitive—behavioural therapy more beneficial than psychodynamic therapy. In the long term no significant benefit was observed with any of the treatments for all outcomes | |

| Quality of study: strong | Follow-up at 18 months and 5 years | |||

| Clark et al (Reference Clark, Tluczek and Wenzel2003) | USA | Mothers and infants (n=39) | Two active intervention groups compared with a waiting-list control group (n=11). The active interventions were mother—infant therapy (n=13) and interpersonal psychotherapy (n=15) delivered by psychologists and social workers | Primary child outcomes: mother—infant interaction and child cognitive development. Child domains of the Parenting Stress Index were used to measure the stress related to the child domain. The Parent—Child Early Relational assessment was used to assess the quality of the mother—child relationship. Bayley Scales of Infant Development — mental scales were used to assess the cognitive and motor development of the infants and toddlers |

| Design: CCT | Age: mothers, mean 31.4 years; infants, mean 8.9 months | No follow-up | Results: mother—infant therapy (n=13) and interpersonal psychotherapy (n=15) were equally effective in terms of mother—infant relationship compared with the waiting-list control group (n=11) but no statistically significant difference was found between the three groups in child cognitive development | |

| Quality of study: moderate |

Murray et al (Reference Murray, Cooper and Wilson2003b ) evaluated the effect of three types of psychological treatment – non-directive supportive counselling, cognitive–behavioural therapy and brief psychodynamic psychotherapy – compared with routine primary care on the mother–child relationship, and continued to measure child outcomes up to 5 years of age (Table 1). The results were adjusted for relationship and behavioural problems prior to treatment, and also for social adversity. At the end of the treatment period (after 4 months), all three treatments significantly improved the quality of the mother–infant relationship but had no effect on the level of behavioural management problems. At 18 months follow-up, Behavioral Screening Questionnaire (BSQ) scores showed a significant difference between the groups (Kruskal–Wallis test=9.04, P=0.03), reflecting greater effects of active treatment compared with routine care. Using a general linear model assuming a gamma distribution (skewed distribution) rather than the usual normal distribution for the BSQ scores, analysis of the treatment groups data showed significant differences for the non-directive counselling group (χ2=12.19, P=0.001), the brief psychodynamic therapy group (χ2=4.06, P=0.03) and the cognitive–behavioural therapy group (χ2=3.52; P=0.06) when compared with the control group. However, scores on infant attachment and child cognitive development were similar in the four groups (Kruskal–Wallis=0.78, P=0.85). At the end of 5 years, child emotional and behavioural difficulties were assessed using maternal reports on the Rutter A2 Parent Scale for Pre-school Children and teacher reports on the Pre-school Behavior Checklist. The differences between the four groups on the Rutter A2 scale did not quite reach significance (Kruskal–Wallis=7.19, P=0.07). Scores on teachers’ reports of child behaviour difficulties (Kruskal–Wallis=0.10, P=0.99) and measures of cognitive development using the McCarthy scales (Kruskal–Wallis=0.55; P=0.91) more clearly showed an absence of differences between the groups. In addition, no significant treatment effect was observed even after controlling for level of social adversity in the linear model.

Clark et al (Reference Clark, Tluczek and Wenzel2003) used a short-term intervention that compared a mother–infant therapy group (n=13) with interpersonal psychotherapy (n=15) and a waiting-list control group (n=11). They examined the effects of treatment on the mother–infant relationship and child cognitive and motor development but did not examine behavioural symptoms or long-term effects. Using ANCOVA with pre-treatment scores and maternal age as covariates, the child domain scores of the Parenting Stress Index were only significant for the ‘child adaptability’ (P=0.036) and ‘reinforces parent’ (P<0.001) domains. Post hoc tests on both of these domains showed the difference was an improvement for the active intervention groups compared with the waiting-list control group, with no statistically significant difference between the two active interventions. Similarly, Parent–Child Early Relational Assessment ratings showed statistically significant group differences for factor 1 (maternal positive affective involvement and verbalisation; P=0.005) and factor 2 (maternal negative effect and behaviour; P=0.035). For factor 1, both of the therapy groups scored higher than the waiting-list group, demonstrating more maternal positive affective involvement and verbalisation with their infants; again, the two intervention groups did not differ from each other. However, for factor 2 the mother–infant therapy group was significantly different from the waiting-list group whereas the interpersonal therapy group was not. Although values were not reported in the paper, its authors commented that no statistically significant difference was found among the three groups for the mental scales of the BSID.

Because of the heterogeneity of these three studies meta-analysis was considered inappropriate, but some qualitative comparison may be worthwhile. Clark et al (Reference Clark, Tluczek and Wenzel2003) had a small sample size and a short-term intervention with no follow-up. Cicchetti et al (Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch and Toth2000) had a much more intensive and prolonged intervention which showed beneficial effects on cognitive development in children. However, there was no long-term follow-up similar to that by Murray et al (Reference Murray, Cooper and Wilson2003b ) to assess the sustainability of the benefits. On the other hand, Murray et al (Reference Murray, Cooper and Wilson2003b ), with comparable sample sizes to the Cicchetti study but a much shorter duration of therapy, showed some short-term benefits from all the treatments for the mother–infant relationship and early child outcome, but did not show any long-term benefit in emotional and behavioural adjustment or cognitive development after 5 years of follow-up.

Mother–infant interaction or relationship

Five studies assessed only mother–infant relationships (Table 2). Once again the interventions varied, ranging from a support group for mothers with depression to interpersonal psychotherapy, making any formal pooling of the results inappropriate.

Table 2 Studies that assessed mother–infant relationships

| Study | Location, design and quality of study | Details of participants | Intervention and delivery | Outcome measurements and results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meager & Milgrom (Reference Meager and Milgrom1996) | Australia | Mothers only (n=20) | A 10-week post-partum support programme (n=10) was compared with a waiting-list control group (n=10). Each session was 1.5 h in duration and conducted by clinical psychologist | Primary outcomes: maternal |

| Design: RCT | Age: others, mean 29.6 years; infants, mean 10.6 months | No follow-up | Secondary child outcome: Parenting Stress Index — child domain Results: no statistically significant difference between support group (n=6) and controls (n=6) in PSI. Child domain sub-scale showed statistically marginal deterioration in control group (P=0.05) between baseline and end of trial | |

| Quality of study: moderate | ||||

| O'Hara et al (Reference O'Hara, Stuart and Gorman2000) | USA | Mothers only (n=120) | Interpersonal psychotherapy (n=48) compared with a waiting-list control group (n=51) over 12 weeks | Primary outcomes: maternal |

| Design: RCT | Age: mothers, mean 29.7 years; infants, not reported | Interpersonal psychotherapy was administered in 12 hour-long individual sessions by psychotherapist with training in this intervention | Secondary outcome: mother—infant relationship, assessed using the self-reported Social Adjustment Scale, which looks at relationship with children older than 2 years, and the Post Partum Adjustment Questionnaire, which looks at relationships with children other than the baby | |

| Quality of study: moderate | No follow-up | Results: statistically significant difference between the groups favouring the interpersonal psychotherapy (n=48) in relationship with children -2 years old and children other than the baby, but no significant difference in relationship with the new baby | ||

| Hart et al (Reference Hart, Field and Nearing1998) | USA | Mothers and infants (n=27 dyads) | Teaching mothers to use Mother's Assessment of the Behavior of her Infant (n=14 dyads) compared with a weekly written report of infants behaviour by control group mothers (n= 13 dyads) | Primary outcome: Neonatal Behavioural Assessment Scale, designed to evaluate behavioural and neurological functioning in neonates and young infants |

| Design: RCT | Age: mothers, mean 21.6 years; infants, mean age at start 40.3 h, at 1 month 32 days | No follow-up | Results: Ratings by examiners showed significant improvement in social interaction and state organisation in treatment group, (where mothers administered MABI periodically at home; n=14 dyads) compared with the control group (no MABI administered by mothers but had a written report; n=13 dyads) | |

| Quality of study: moderate | ||||

| Horowitz et al (Reference Horowitz, Bell and Trybulski2001) | USA | Mothers and infants (n=122) | Home visits only (n=57) compared with home visits and interaction coaching for at-risk parents and infants (n=60) | Primary outcome: mother—infant responsiveness, assessed with the Dyadic Mutuality Code |

| Design: RCT | Age: mothers, mean 31 years; infants, not reported | Three home visits over 18 weeks by research nurse, and interaction coaching delivered by advanced practice nurses and research assistants. Each session lasted 15 min | Results: statistically significant difference in favour of interaction coaching group (n=60) compared with group with only home visits (n=57) for increase in responsiveness (P=0.006); this was maintained over time (P=0.025) | |

| Quality of study: moderate | No follow-up | |||

| Onozawa et al (Reference Onozawa, Glover and Adams2001) | UK | Mothers and infants (n=34) | Support group only (n=12) as controls compared with infant massage in addition to support group (n=13) | Primary outcome: mother—infant interaction, assessed by video recording and rated according to global rating for mother—infant interactions at 2 months. This rates the maternal contribution, infant's contribution and the interaction itself |

| Design: RCT | Age: mothers, median 18-45 years; infants, 9 weeks | Support group consisted of 30 min per week informal group discussion for 5 weeks. Infant massage consisted of a short period of relaxation followed by infant massage for 1 h by trained instructors, in addition to support group for 5 weeks | Results: statistically significant difference in favour of infant massage (n=10) compared with the support group (n=12), with marked improvement in mother—infant interaction (P=0.0004) | |

| Quality of study: moderate | No follow-up | |||

| Glover et al (Reference Glover, Onozawa and Hodgkinson2002)1 | UK | Mothers and infants (n=34) | Support group only (n=12) as controls compared with infant massage in addition to support group (n=13) | Primary Outcome: mother—Infant interaction, assessed by the video recording and rated as above |

| Design: RCT | Age: mothers, median 18-45 years; infants, median 9 weeks | Intervention described above (Onozawa et al, 200 1) | Results: statistically significant improvement in mother—infant interaction was achieved for the mothers who attended the massage class (n=12) compared with the control group (n=12) over time — from baseline to the final session (P<0.00 1) | |

| Quality of study: moderate |

Two of the studies (Reference Meager and MilgromMeager & Milgrom, 1996; Reference O'Hara, Stuart and GormanO'Hara et al, 2000) had only mothers with postnatal depression as participants. Meager & Milgrom (Reference Meager and Milgrom1996) observed changes in the children but had small sample sizes (10 in each arm). They measured scores on the Parenting Stress Index which did not change significantly over time for either group. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess changes in child domains and to explore the variation between ‘mothers’ and ‘time spent by mothers in support programme’ over all 10-week time points. This did show a deterioration in the child domain subscale scores, with a post hoc least significant difference over time of 13.42 (P=0.05) for the control group but not for the intervention group. Although the support group showed marginal benefits, this was based on a sub-scale reflecting the mother's perception of the infant rather than the child outcome itself. In the other study with only mothers as participants, O'Hara et al (Reference O'Hara, Stuart and Gorman2000) assessed the effect of interpersonal psychotherapy; this was a larger study but conducted over only two weeks. The results, repeated ANOVA measures, favoured interpersonal psychotherapy over control for two of the sub-scales of the Social Adjustment Scale and the Postpartum Adjustment Questionnaire (PPAQ) reflecting the quality of the parent–child relationship. These sub-scales were ‘relationship with older children more than 2 years’ (P<0.05) and ‘mother's relationships with children other than the baby’ (P=0.005). However, the PPAQ showed no significant difference between the two groups with respect to the ‘relationship with the new baby’ sub-scale (P=0.13).

Three studies (Reference Hart, Field and NearingHart et al, 1998; Reference Horowitz, Bell and TrybulskiHorowitz et al, 2001; Reference Onozawa, Glover and AdamsOnozawa et al, 2001) had both mothers and their infants as participants, but once again interventions varied. Horowitz et al (Reference Horowitz, Bell and Trybulski2001) studied the effects of ‘interactive coaching’ on the mother–infant relationship. Here the coached group had a statistically significant higher Dyadic Mutuality Code mean score than the control group at 10–14 weeks (P=0.002) and at 14–18 weeks (P=0.029). Responsiveness between mother and the infant using repeated measures of ANOVA also showed a significant difference between the treatment and control groups (P=0.006) and over time (P=0.025). Thus, the increase in responsiveness that occurred following the intervention was maintained at least to 18 weeks. A study reported on by both Onozawa et al (Reference Onozawa, Glover and Adams2001) and Glover et al (Reference Glover, Onozawa and Hodgkinson2002) compared infant massage with a support group. Mother–infant interactions were assessed by video recording and rated as ‘maternal contribution to the interaction’, ‘infant's contribution’ and the mother–infant interaction itself. Onozawa et al (Reference Onozawa, Glover and Adams2001) found an improvement in the maternal–infant interaction in the massage group compared with the support group. Glover et al (Reference Glover, Onozawa and Hodgkinson2002) reported the same results slightly differently, presenting the mother–baby interaction scores over time, showing that for mothers who attended the massage class a statistically significant improvement was achieved (P<0.001) compared with the control group.

Hart et al (Reference Hart, Field and Nearing1998) reported a different intervention in which the researchers sought to assess whether training depressed mothers to examine their infants might improve their child's developmental outcomes. Those in the intervention group (14 mother and infant pairs) observed an administration of the Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS) soon after the delivery of the baby, by a trained examiner. The examiner explained the significance of various infant behaviours, such as turning toward a sound source and tuning out distractions. Mothers were then given feedback on their infant's behaviour, and given the opportunity to discuss this. After the administration of NBAS by examiners, mothers were taught to administer a similar instrument, the Mother's Assessment of the Behavior of her Infant (MABI), independently. They were then instructed to repeat the administration at home at 1-week intervals for 1 month. For the control group (13 mother and infant pairs), mothers were not present when the NBAS was administered by the examiners at the delivery, although they were asked to periodically complete written assessments at home of their parenting attitudes and the infant's development. Outcomes consisted of both examiner and maternal ratings on the NBAS at the end of the trial. Ratings of infants by examiners (unaware of the mother's group status) revealed that after 1 month, infants in the experimental group (where mothers administered the MABI periodically at home) were performing better than the infants in the control group for social interaction (P<0.05) and state organisation (P<0.05). Mothers in both groups, although not significantly different from each other, rated their infants as showing significant improvements over time for social, motor and state organisation indicative of developmental progress. The authors concluded that NBAS/MABI enhanced social interaction and state organisation in children, even though mothers’ perceptions of their infant's behaviour were not different between the two groups.

Overall, these five studies measuring the mother–infant relationship showed improvement irrespective of the type of intervention and the target population (either mothers only, or infants along with mothers). However, the instruments used to measure outcome in these studies need to be taken into consideration. The Parenting Stress Index used by Meager & Milgrom (Reference Meager and Milgrom1996), measured parental adjustment to parenting rather than outcomes in children per se. In the study by Hart et al (Reference Hart, Field and Nearing1998), the measure was the same as the intervention that had been used more often in the active treatment group. It is therefore unclear whether this study simply detected the effects of the infants practising the assessment rather than any genuine therapeutic effect.

DISCUSSION

With many women experiencing postnatal depression and the apparent ineffectiveness of preventive strategies for postnatal depression in women at high risk of this disorder, early detection and treatment are increasingly being recognised as the priority (Reference Ogrodniczuk and PiperOgrodniczuk & Piper, 2003; Reference DennisDennis, 2005). Despite the wide range of treatments (including antidepressants, progesterone, cognitive–behavioural therapy and interpersonal therapy) that are available and beneficial for mothers, an important question is whether treatment of postnatal depression has demonstrable benefits for children, given the significant short-term and long-term consequences of the disorder on both the baby and its siblings.

This review is the first to search systematically for clinical randomised controlled trials that assessed the effects of treatment of postnatal depression on the physical and mental health of children rather than that of the mothers. We were also interested to find out whether this depended upon the type of treatment and if it was influenced by maternal variables such as persisting depression or psychosocial adversity.

Methodological issues and limitations

Despite a comprehensive search, only eight studies (nine papers) assessing child outcomes in response to postnatal depression treatment were identified, since most studies focused only on maternal outcomes. Treatment interventions in the identified studies varied widely, but all contained elements that sought to influence child development or the mother–child relationship. This highlights a potentially important issue in relation to the aetiology of postnatal depression, in that it may be driven by maternal difficulties in forming a relationship with the infant. The interventions described in this review may serve to treat depression by addressing these underlying relationship conflicts directly, or through simple effects on the depression with naturally positive consequences for the relationship. Most studies were not able to address this distinction. Improved infant behaviour could have been a direct reflection of improvement in maternal mood. This is particularly likely for some of the outcome measurement tools used, such as the Parenting Stress Index (Reference Meager and MilgromMeager & Milgrom, 1996; Reference Clark, Tluczek and WenzelClark et al, 2003) which did not measure child behaviour directly but were self-report measures, reflecting maternal attitudes and perceptions. It seems likely that scores on these measures would improve with better mood, irrespective of whether the child's behaviour or the relationship had actually improved.

Nevertheless, for studies that did measure child outcomes directly, it was impossible to disentangle whether improvement of maternal–infant relationship would result from simple treatment of the postnatal depression, or whether this improvement is dependent on a treatment that directly addresses mother–infant relationship issues and involves infants in treatment. One possible pointer is that the interventions by Cicchetti et al (Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch and Toth2000) and Murray et al (Reference Murray, Cooper and Wilson2003b ) are likely to have been of equal benefit in the treatment of depression; this suggests that the specific benefits found in the study by Cicchetti et al (Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch and Toth2000) stemmed from positive influences on the mother–infant relationship. Further, our review did not cover interventions in the prenatal stage or interventions directed at mothers who were not clinically depressed.

A final methodological point that emerged from our review concerned group therapies and therapists’ skill levels. Although patient numbers might have been high, therapists tended to be few in number and their experience varied; some were students. Although usually training had been provided to the study therapists (Reference Clark, Tluczek and WenzelClark et al, 2003), it is possible that outcomes reflected individual differences between therapist skill levels rather than differences between treatments unless it was controlled for as in the study by Murray et al (Reference Murray, Cooper and Wilson2003b ) which showed no specialist therapist effect. Consequently, potential differences between treatments can be confounded by differences among those who are delivering the treatments.

Findings of the review

Overall, we found that all treatments for postnatally depressed mothers had some benefits in improving the quality of the mother–infant interaction and relationship, the level of behavioural management problems and cognitive development in children. However, it is important to highlight that observed improvements were based on only a few studies, with very different interventions and measurement tools. Only the study by Cicchetti et al, (Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch and Toth2000), assessing toddler parent psychotherapy as an intervention, showed significant improvement in the children's cognitive development. In this study the intervention was much more intensive and longer-lasting. The outcomes were measured objectively using standard validated measuring tools, and the degree of improvement following the intervention is likely to have been clinically and developmentally significant. However, this study did not follow the children up to see if the benefits were sustainable. In contrast, the long-term follow-up study by Murray et al (Reference Murray, Cooper and Wilson2003b ) (5 years of follow-up) failed to show sustainability of short-term benefits, but it had an intervention of shorter duration (only 18 weeks).

Improvements observed in the infants could also have been a direct reflection of improvement in maternal depression scores. All the studies, irrespective of the child outcome measured, made an assessment of maternal depression scores and reported improvement in the women's depression levels. Although no detailed analysis was carried out for this review regarding the outcome in mothers, none of the studies made any attempt to explore an association between the improved maternal depression scores and the improved infant outcomes. From this, there is not enough evidence to show if the improvement in maternal–infant relationship was a consequence of improvement in maternal depression alone or if there was an additional intervention or participant element that could have improved the cognitive status of the children.

Implications for practice

From the evidence available, treatment interventions in mothers for postnatal depression seem to have some benefits for the mother–infant relationship. However, for improving cognitive development in children, in spite of one high-quality study in our review providing strong evidence of benefits, the long-term sustainability needs to be assessed. Cognitive development in children, along with mother–infant relationships, may also be best improved with sustained interventions over a longer period.

Implications for research

In spite of the significant impact of postnatal depression on children, most treatment trials for this disorder treat mothers in isolation and concentrate on maternal outcomes. Even in studies with assessments of both maternal and child outcomes, no attempt had been made to determine whether there was any association between the maternal and child outcomes, which could have considerable implications. A well-conducted randomised controlled trial with adequate power and long-term follow-up, comparing two different potentially effective interventions identified in this review, is warranted to try to identify the most effective intervention and assess the impact of treatment of postnatal depression on children. Furthermore, combining treatments for maternal depression (such as antidepressant medication) with therapies focused on the mother–infant relationship and investigating associations between improved maternal depression and infant outcomes may also be worthy of consideration. Studies should also assess the effect of treatment using directly rated child measures rather than relying on maternal self-reporting. Given that our review did not cover interventions in the prenatal stage or interventions directed at mothers who were not clinically depressed, future research should consider this group.

This review is unable to provide strong evidence for a single effective intervention to improve cognitive development in children, given the disparate interventions. The research does, however, suggest that long-term, intensive interventions directed at the mother–infant relationship may bring about benefits in cognitive development of the child. These potentially effective interventions should be further explored with well-powered trials so that comparisons can be made in order to achieve improvement and sustainability over a long period.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Scottish Evidence Based Child Health Unit, National Health Service Scotland.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.