Early intervention services have been developed to address the needs of individuals with early psychosis. Typically, there is a delay between the onset of the first episode of psychosis and receiving an effective treatment – a period of untreated psychosis. Reference Harrigan, McGorry and Krstev1 Reducing this duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) for people with schizophrenia may lead to an improved prognosis. Reference Harrigan, McGorry and Krstev1–Reference Bottlender, Sato and Jager4 Early intervention services aim to detect emergent symptoms, reduce DUP, and improve early access to effective treatment, particularly in the ‘critical period’ (the first 3–5 years following onset). Reference Birchwood, McGorry and Jackson5–Reference Lieberman and Fenton7 Although at the time there was little evidence for the effectiveness of this approach, early intervention services were developed in Australia, the USA, Canada, New Zealand and elsewhere; and the widespread deployment of such services was recommended in the National Service Framework for Mental Health 8 and in the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline on schizophrenia for England and Wales. 9

Since then, the provision of early intervention services has steadily increased, Reference Singh, Wright, Burns, Joyce and Barnes10 with 145 early intervention services currently operating in the UK, serving about 15 750 individuals (Care Services Improvement Partnership, personal communication, 2009). Early intervention teams have also gradually evolved and now often consist of community-based multidisciplinary mental health teams that provide a combination of pharmacotherapy, family intervention, cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), social skills training, problem-solving skills training, crisis management and case management. Reference Craig, Garety, Power, Rahaman, Colbert and Fornells-Ambrojo11,Reference Grawe, Falloon, Widen and Skogvoll12 However, although the evidence base for early intervention services is growing, their specific benefits have not been clearly demonstrated. Reference Marshall and Rathbone13,Reference Penn, Waldheter, Perkins, Mueser and Lierberman14 Therefore as part of an update of the NICE guideline on schizophrenia, 9,15 we conducted a systematic review of early intervention services for people with a first or early episode of psychosis. Because early intervention services typically include an individually tailored combination of evidence-based psychological interventions, we also examined the data on the separate use of CBT and family intervention used specifically in the context of early psychosis.

Method

Search strategy and selection criteria

We identified randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of early intervention services, CBT or family intervention for people with early psychosis, using the original schizophrenia guideline 9 and five bibliographic databases (CINAHL, CENTRAL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO). The database search was conducted in September 2009 and restricted to English language papers or papers with an abstract in English. Full details of the search strategy can be found in the online supplement. Additional papers were identified by searching the reference list of retrieved articles, tables of contents of relevant journals, recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses of interventions in schizophrenia, and suggestions made by members of the schizophrenia Guideline Development Group (a comprehensive review protocol can be found in the updated edition of the full schizophrenia guideline, available from www.nccmh.org.uk). 15

Early psychosis was defined as a clinical diagnosis of psychosis within 5 years of the first psychotic episode or presentation to mental health services. Interventions addressing high-risk groups or ‘pre-psychotic’/prodromal populations were excluded, as were studies where the main focus of the intervention was not on psychosis or where the duration since the first psychotic episode was greater than 5 years.

Quality assessment

All trials meeting the eligibility criteria were assessed for methodological quality using a modified version of the SIGN checklist. 16 Trials that were judged to be of adequate quality were included in the review. Trials that were not clearly described as randomised were excluded as were those with fewer than ten participants per intervention arm.

Data extraction

Two of the authors (V.B. and J.M.) entered study details into a database and assessed methodological quality. Three of the authors (V.B., C.W. and P.P.) extracted outcome data into Review Manager (RevMan version 5.0.18 for Windows XP; The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). The assessment of study quality and all outcome data were double-checked by one author (C.W.) for accuracy, with disagreements resolved by discussion.

Where available, data were extracted for the following outcomes: hospital admission; psychotic relapse (if appropriate criteria were used); DUP; and mean positive and negative symptoms as measured using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler17 Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), Reference Ventura, Lukoff, Neuchterlein, Liberman, Green and Shaner18 Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS), Reference Andreasen19 and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Reference Andreasen20 Outcome data were extracted at both end of treatment and follow-up (based on mean end-point scores). In light of the fundamental aims of early intervention services, Reference Grawe, Falloon, Widen and Skogvoll12 data on remaining in contact with services and accessing psychosocial treatments were also extracted.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was used, where appropriate, to synthesise the evidence using RevMan. Where possible, intention-to-treat with last observation carried forward data were used in the analyses. For binary outcomes, this approach assumes that participants leaving the study early, for whatever reason, had an unfavourable outcome. We calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) for continuous outcomes, and relative risk (RR) for binary outcomes. For consistency, data from all outcomes (continuous and binary) were entered into RevMan in such a way that negative effect sizes or relative risks less than one favoured the active intervention. The number needed to treat for benefit (NNTB) Reference Altman21 was calculated for statistically significant relative risks. Data from more than one study were pooled using a random-effects model, regardless of heterogeneity between trials, as this has recently been shown to be the most appropriate model in most circumstances. Reference Schmidt, Oh and Hayes22 Summary effects were assessed for clinical importance, taking into account both the point estimate and the associated 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

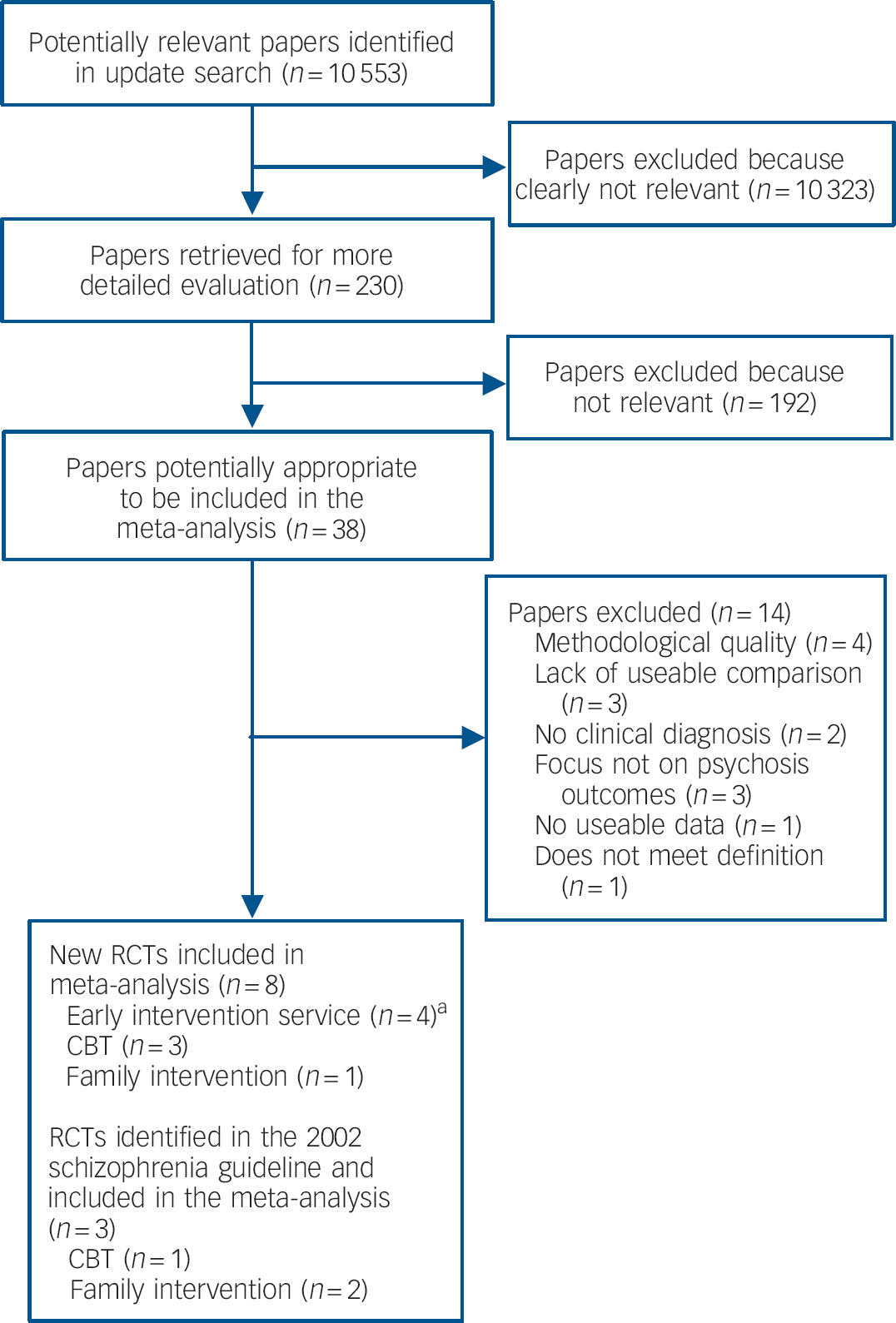

The search process and total number of trials included in the review are illustrated in Fig. 1. Details of all included trials can be found in Table 1, with further information about included and excluded studies available in online Tables DS1 and DS2.

Table 1 Characteristics of included trials

| Study (primary paper) | Total participants, n | Treatment groups | Duration and frequency of treatment | Standard care comparison group | Outcomes extracted for this review |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early intervention services | |||||

| COAST Reference Kuipers, Holloway, Rabe-Hesketh and Tennakoon23 | 59 | Early intervention service including psychological interventions as required | 9 months follow-up reported, with service available 7 days a week including nights | Local available CMHT services | Leaving the study for any reason, PANSS not extracted as n < 10 in comparison arm at 9 months |

| LEO Reference Craig, Garety, Power, Rahaman, Colbert and Fornells-Ambrojo11 | 144 | Early intervention service established on principles of assertive outreach including psychosocial interventions | 12 and 18 months follow-up reported, with extended hours service including weekends | Local available CMHT services | Leaving the study early, relapse, hospital admission, remaining in contact with services, receiving psychosocial interventions, positive symptoms (PANSS), negative symptoms (PANSS) |

| OPUS Reference Petersen, Jeppesen, Thorup, Abel, Ohlenschlaeger and Christensen24 | 547 | Early intervention service: assertive community treatment, family intervention and social skills training | 2-year treatment duration, with service available between 8am and 5pm with a crisis plan for each patient | Services offered by local community mental health centres | Leaving the study early, hospital admission, remaining in contact with services, positive symptoms (PANSS), negative symptoms (PANSS) |

| OTP Reference Grawe, Falloon, Widen and Skogvoll12 | 50 | Early intervention service: integrated treatment with structured psychological interventions | 2-year treatment duration, with treatment session provided weekly – monthly over 2 years | Regular clinic-based services (80% from hospital out-patient, 20% local community general health services) | Leaving the study early, hospital admission, relapse receiving psychosocial interventions |

| Cognitive–behavioural therapy | |||||

| Jackson et al Reference Jackson, McGorry, Edwards, Hulbert, Henry and Harrigan25 | 91 | Individual CBT: cognitively oriented psychotherapy | 40-minute session weekly or fortnightly for up to 12 months | Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre (EPPIC) | Positive symptoms (BPRS), negative symptoms (SANS), hospital admission |

| Lecomte et al Reference Lecomte, Leclerc, Corbière, Wykes, Wallace and Spidel28 | 75 | Group-based CBT tailored to first-episode psychosis | 24 treatment sessions delivered twice a week for 3 months | Local mental health clinic or early intervention programmes | Positive symptoms (BPRS), negative symptoms (BPRS) |

| Lewis et al Reference Lewis, Tarrier, Haddock, Bentall, Kinderman and Kingdon26 | 203 | Individual CBT: Study of Cognitive Reality Alignment Therapy in Early Schizophrenia | 15–20 h within 5 weeks with booster sessions at a further 2 weeks, 1, 2 and 3 months | Routine clinical care from local mental health units | Positive symptoms (PANSS), negative symptoms (PANSS), relapse, hospital admission |

| Wang et al Reference Wang, Li, Zhao, Pan, Feng and Sun27 | 251 | Individual CBT offered at recovery stage | Six weekly 40- to 50-minute sessions | Hospital services including clozapine or risperidone | Positive symptoms (PANSS), negative symptoms (PANSS), hospital admission |

| Family intervention | |||||

| Goldstein et al Reference Goldstein, Rodnick, Evans, May and Steinberg29 | 104 | Family intervention: crisis oriented, individually delivered | Six weekly intervention sessions | Standard treatment with either low- or high-dose fluphenazine | Relapse (end of treatment and 6-month follow-up) |

| Leavey et al Reference Leavey, Gulamhussein, Papadopoulous, Johnson-Sabine, Blizard and King30 | 106 | Family intervention: education and problem-solving | Seven 1 h sessions | Usual care from psychiatric services and CMHTs | Hospital admission (end of treatment) |

| Zhang et al Reference Zhang, Wang, Li and Phillips31 | 78 | Family intervention: group and individual sessions focused on education | 18 months with contact every 1–3 months | Standard hospital out-patient services | Hospital admission (end of treatment) |

Early intervention services

Four published trials (n = 800) were included in the meta-analysis of early intervention services: COAST (Croydon Outreach and Assertive Support Team); Reference Kuipers, Holloway, Rabe-Hesketh and Tennakoon23 LEO (Lambeth Early Onset); Reference Craig, Garety, Power, Rahaman, Colbert and Fornells-Ambrojo11 the OPUS trial; Reference Petersen, Jeppesen, Thorup, Abel, Ohlenschlaeger and Christensen24 and OTP (Optimal Treatment Project). Reference Grawe, Falloon, Widen and Skogvoll12 Inspection of the Cochrane review of early interventions in psychosis Reference Marshall and Rathbone13 identified three additional trials; however, these were excluded as they failed to meet our inclusion criteria regarding the population studied and comparison used. All included trials recruited participants from local mental health services such as community mental health teams, in-patient and out-patient services. However, the trials varied as to whether the participant was a new referral, with LEO Reference Craig, Garety, Power, Rahaman, Colbert and Fornells-Ambrojo11 including only those making contact for the first or second time, whereas COAST, Reference Kuipers, Holloway, Rabe-Hesketh and Tennakoon23 OPUS Reference Petersen, Jeppesen, Thorup, Abel, Ohlenschlaeger and Christensen24 and OTP Reference Grawe, Falloon, Widen and Skogvoll12 considered people who had a documented first contact within a specified time period, ranging from 12 weeks to 5 years. Interventions often included a case manager or care coordinator, with a lower case-load than in standard care. In addition to medication management, all participants allocated to early intervention services were offered a range of psychosocial interventions, including CBT, Reference Craig, Garety, Power, Rahaman, Colbert and Fornells-Ambrojo11,Reference Grawe, Falloon, Widen and Skogvoll12,Reference Kuipers, Holloway, Rabe-Hesketh and Tennakoon23 social skills training Reference Petersen, Jeppesen, Thorup, Abel, Ohlenschlaeger and Christensen24 and family intervention Reference Grawe, Falloon, Widen and Skogvoll12,Reference Kuipers, Holloway, Rabe-Hesketh and Tennakoon23,Reference Petersen, Jeppesen, Thorup, Abel, Ohlenschlaeger and Christensen24 or family counselling, Reference Craig, Garety, Power, Rahaman, Colbert and Fornells-Ambrojo11 and vocational strategies such as supported employment. Reference Craig, Garety, Power, Rahaman, Colbert and Fornells-Ambrojo11,Reference Grawe, Falloon, Widen and Skogvoll12,Reference Kuipers, Holloway, Rabe-Hesketh and Tennakoon23 The psychosocial and vocational interventions were usually adapted to the needs of first-episode psychosis and offered on an ‘as-required’ basis. The frequency and duration of contact differed between trials, with the duration of the intervention lasting up to 2 years. Outcomes were reported at 9 months to 5 years post-randomisation.

Participants receiving early intervention services, when compared with those receiving standard care, were less likely to relapse (35.2% v. 51.9%; NNTB for one extra patient to avoid relapse 6, 95% CI 3 to 25; heterogeneity I 2 = 0%, P = 0.67) or be admitted to hospital (28.1% v. 42.1%; NNTB = 7, 95% CI 5 to 7; heterogeneity I 2 = 0%, P = 1.00) (Table 2). Early intervention services also significantly reduced positive symptoms with a pooled SMD of –0.21 (95% CI –0.42 to –0.01; heterogeneity I 2 = 9%, P = 0.29) and negative symptoms with a pooled SMD of –0.39 (95% CI –0.57 to –0.20; heterogeneity I 2 = 0%, P = 0.38). The rate of discontinuation for any reason was lower for early intervention services compared with standard care (27.0% v. 40.5%; NNTB = 8, 95% CI 5 to 14; heterogeneity I 2 = 40%, P = 0.17). In terms of access and engagement with treatment, although generally high, participants in early intervention services were more likely to remain in contact with the index mental health team (91.4% v. 84.2%; NNTB = 13, 95% CI 4 to); heterogeneity I 2 = 0%, P = 0.79), and were twice as likely to receive a psychosocial intervention (36.6% v. 14.0%; NNTB = 5, 95% CI 4 to 6; heterogeneity I 2 = 74%, P = 0.02).

Table 2 Analysis of interventions for early psychosis compared with standard care (random-effects model)

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of selection of papers for inclusion in the clinical review.

CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; RCTs, randomised controlled trials. a. Includes RCTs published in multiple papers.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy

Four published trials of CBT Reference Jackson, McGorry, Edwards, Hulbert, Henry and Harrigan25–Reference Lecomte, Leclerc, Corbière, Wykes, Wallace and Spidel28 were included in the review (n = 620). One paper Reference Wang, Li, Zhao, Pan, Feng and Sun27 published in Chinese but with an English abstract was translated subsequent to publication of the schizophrenia (update) guideline 15 and included in this analysis.

Participants were recruited from a range of services which included early intervention services, community mental health clinics and in-patient psychiatric wards. In two trials, participants were exclusively in their first episode of psychosis. Reference Jackson, McGorry, Edwards, Hulbert, Henry and Harrigan25,Reference Wang, Li, Zhao, Pan, Feng and Sun27 Another trial Reference Lewis, Tarrier, Haddock, Bentall, Kinderman and Kingdon26 additionally included participants who had been admitted for a second time, providing the episode occurred within 2 years of the first admission (17% of their sample). The fourth trial Reference Lecomte, Leclerc, Corbière, Wykes, Wallace and Spidel28 included participants who had consulted a mental health professional for psychosis for the first time in the past 2 years. Cognitive–behavioural therapy was delivered individually in three out of the four trials, Reference Jackson, McGorry, Edwards, Hulbert, Henry and Harrigan25–Reference Wang, Li, Zhao, Pan, Feng and Sun27 with a group-based approach in the fourth. Reference Lecomte, Leclerc, Corbière, Wykes, Wallace and Spidel28 Two of the interventions specifically adapted the CBT approach for early psychosis, Reference Jackson, McGorry, Edwards, Hulbert, Henry and Harrigan25,Reference Lecomte, Leclerc, Corbière, Wykes, Wallace and Spidel28 with the remaining two interventions targeting positive symptoms Reference Lewis, Tarrier, Haddock, Bentall, Kinderman and Kingdon26 and insight building. Reference Wang, Li, Zhao, Pan, Feng and Sun27 The frequency of sessions and the duration of treatment varied across trials, with the total duration ranging from 5 weeks (plus booster sessions) Reference Lewis, Tarrier, Haddock, Bentall, Kinderman and Kingdon26 to 1 year. Reference Jackson, McGorry, Edwards, Hulbert, Henry and Harrigan25

At up to 2 years post-treatment follow-up, when compared with standard care alone, CBT significantly reduced mean positive symptoms with a pooled SMD of –0.60 (95% CI –0.79 to –0.41; heterogeneity I 2 =0%, P = 0.44) and mean negative symptoms with a pooled SMD of –0.45 (95% CI –0.80 to –0.09; heterogeneity I 2 = 62%, P = 0.07). These benefits were not evident at the end of treatment in terms of both positive (SMD = –0.05, 95% CI –0.22 to 0.12; heterogeneity I 2 = 0%, P = 0.92) and negative symptoms (SMD = 0.03, 95% CI –0.17 to 0.23; heterogeneity I 2 = 0%, P = 0.41), or relapse within the 2-year follow-up period (27.8% v. 32.2%, P= 0.44; heterogeneity I = 79%, P = 0.03). Rates of hospital admission up to 2 years follow-up also failed to demonstrate any additional benefit for CBT compared with standard care (38.4% v. 38.5%, P= 0.94; heterogeneity I 2 = 0%, P = 0.36).

Family intervention

Three trials (n = 288) assessing family intervention in early psychosis were included in the review. Reference Goldstein, Rodnick, Evans, May and Steinberg29–Reference Zhang, Wang, Li and Phillips31 Participants were recruited from psychiatric services, including in-patient units, and were either first or second admissions, Reference Goldstein, Rodnick, Evans, May and Steinberg29,Reference Zhang, Wang, Li and Phillips31 or had made first contact with services within the past 6 months. Reference Leavey, Gulamhussein, Papadopoulous, Johnson-Sabine, Blizard and King30 Two trials Reference Goldstein, Rodnick, Evans, May and Steinberg29,Reference Leavey, Gulamhussein, Papadopoulous, Johnson-Sabine, Blizard and King30 included the individual with psychosis in the family sessions, whereas in Zhang et al Reference Zhang, Wang, Li and Phillips31 the majority of family sessions did not include the patient. The interventions delivered in each trial included an element of psychoeducation and problem-solving, with crisis management also evident in one trial. Reference Goldstein, Rodnick, Evans, May and Steinberg29 Interventions varied in their mode of delivering, with two trials Reference Goldstein, Rodnick, Evans, May and Steinberg29,Reference Leavey, Gulamhussein, Papadopoulous, Johnson-Sabine, Blizard and King30 utilising an individual family approach and the remaining trial combining individual and group-based family sessions. Only one trial Reference Goldstein, Rodnick, Evans, May and Steinberg29 reported relapse and a further two trials Reference Leavey, Gulamhussein, Papadopoulous, Johnson-Sabine, Blizard and King30,Reference Zhang, Wang, Li and Phillips31 reported hospital admission; these outcomes were combined to increase statistical power.

The combined analysis indicated that at the end of treatment, participants receiving family intervention were less likely to relapse or be admitted to hospital compared with those receiving standard care (14.5% v. 28.9%; NNTB = 7, 95% CI 4 to 20; heterogeneity I 2 = 0%, P = 0.40). At up to 2 years follow-up, one study Reference Goldstein, Rodnick, Evans, May and Steinberg29 reported a numerically lower risk of relapse (23.1% v. 30.8%, P = 0.38), although this was not statistically significant. None of the included family intervention trials provided data on mean positive and negative symptoms.

Discussion

Main findings

For people with early psychosis, in four trials of early intervention services, four trials of CBT, and three trials of family intervention, meta-analysis demonstrated advantages over standard care. By the end of treatment, early intervention services produced clinically important reductions in the risk of both relapse and hospital admission. In addition, small effects favouring early intervention services were shown in terms of reduced symptom severity and improved access to and engagement with treatment (including psychological therapies). Family intervention also produced clinically important reductions in the risk of relapse and hospital admission when compared with standard care. In the 2 years following the intervention, medium effects favouring CBT were demonstrated in terms of reduced positive and negative symptom severity. We found no data on the effect of family intervention on symptoms and insufficient evidence to reach a conclusion about the impact of CBT on relapse or hospital admission.

Early intervention services

Compared with a previous review of early interventions in psychosis, Reference Marshall and Rathbone13 our meta-analysis found stronger evidence to support the effectiveness of early intervention services overall. The earlier review included fewer trials that specifically focused on service-level interventions delivered during the ‘critical period’ following onset of psychosis. Furthermore, although the previous review included both discrete psychosocial and multicomponent service-level interventions, there was a lack of comparable trials for any conclusions to be drawn. Our findings do, however, substantiate those previously reported in a narrative review of randomised and non-randomised studies by Penn and colleagues, Reference Penn, Waldheter, Perkins, Mueser and Lierberman14 who concluded that early interventions had beneficial effects across a range of domains, although further investigation was needed to establish the robustness of these findings. Reference Penn, Waldheter, Perkins, Mueser and Lierberman14 Our review attempts to overcome these limitations and provides the first meta-analytic evidence indicating that both early intervention services and discrete psychological interventions improve outcomes for early psychosis.

In the present review, the early intervention services provided in all of the trials included the provision of psychosocial interventions, pharmacological treatment and some form of case management involving smaller case-loads (1:10) and an assertive approach to treatment. All of the components were tailored to meet the needs of the individual patient and offered at the earliest opportunity. These elements were not present in treatment as usual, although an assertive approach to treatment is so common that it cannot be specifically excluded. The psychological interventions used in the included trials were CBT and either family intervention Reference Grawe, Falloon, Widen and Skogvoll12,Reference Kuipers, Holloway, Rabe-Hesketh and Tennakoon23,Reference Petersen, Jeppesen, Thorup, Abel, Ohlenschlaeger and Christensen24 or family counselling. Reference Craig, Garety, Power, Rahaman, Colbert and Fornells-Ambrojo11 It is possible that the reduced case-loads and more appropriate use of pharmacological interventions within early intervention services may account for some of the clinical and statistically important improvements demonstrated. Although further research is needed to investigate the beneficial contributions of these features of early intervention, given the positive effects of CBT and family intervention when delivered as discrete interventions for people with early psychosis, it is just as likely that these two psychosocial interventions have contributed to some of the benefits of early intervention services in this review.

Gleeson and colleagues Reference Gleeson, Cotton, Alvarez-Jimenez, Wade, Gee and Crisp32 recently demonstrated that the addition of a cognitive–behavioural and family therapy-based relapse prevention programme to an early intervention service for individuals in remission from a first episode of psychosis was more likely to prevent or significantly delay a second episode when compared with an early intervention service alone. In this trial the early intervention service alone included only family psychoeducation and peer support. This study provides some evidence to support our hypothesis: that an important part of the overall effectiveness of the early intervention teams included in our meta-analysis derives from the inclusion of two evidence-based psychological interventions, namely, CBT and family intervention. In our review we have shown that the likelihood of a service user receiving a psychosocial intervention in an early intervention team is double that found in a community mental health team.

Limitations

One limitation of the present review is the paucity of trials included in each meta-analysis. We excluded trials focusing on high-risk groups or prevention of psychosis because of the possible ethical implications of targeting interventions at these individuals. Reference Birchwood, McGorry and Jackson5 Another limitation is the variability in long-term follow-up measures available in different trials making some comparisons difficult. Only one trial of an early intervention service provided long-term data (up to 5 years post-randomisation), Reference Petersen, Jeppesen, Thorup, Abel, Ohlenschlaeger and Christensen24 whereas all four trials of CBT Reference Jackson, McGorry, Edwards, Hulbert, Henry and Harrigan25–Reference Lecomte, Leclerc, Corbière, Wykes, Wallace and Spidel28 and one of family intervention Reference Goldstein, Rodnick, Evans, May and Steinberg29 included long-term follow-up measures. Therefore, it remains to be determined whether the effects of early intervention services are sustained.

Psychological interventions

Despite the limitations, our findings regarding the efficacy of CBT and family intervention are consistent with, and reflect, the wider evidence base found in the treatment and management of later psychotic episodes. The updated edition of the schizophrenia guideline 15 recommends that both interventions should be offered to people experiencing an acute episode of schizophrenia and for promoting recovery in those with established schizophrenia.

The evidence presented here suggests that CBT for early psychosis has longer-term benefits in terms of reducing symptom severity. Consistent with the wider evidence base for CBT for established psychosis, the present review failed to find any evidence that CBT reduced relapse rates in early psychosis, which suggests that the main benefits of this intervention are likely to be a reduction in symptoms and distress in early and established psychosis. This finding confirms a recent review assessing both RCTs and non-randomised studies of CBT in first-episode psychosis, which also failed to demonstrate positive effects on relapse and readmission. Reference Morrison33

Although the number of RCTs for family interventions for early psychosis was limited in our review, the evidence is consistent with the larger body of evidence for the role of family interventions in established schizophrenia, in that family intervention reduced combined hospital admission and relapse rates. The review conducted for the updated edition of the schizophrenia guideline 15 also found robust evidence for the efficacy of family intervention in established schizophrenia in reducing symptoms at the end of treatment. However, in the present review, none of the included trials reported measures that allowed us to assess this in the context of early psychosis. It is, therefore, anticipated that family intervention in first-episode psychosis may also reduce symptom levels.

Critical period

The studies included in the present review did not provide any data relating to DUP, as all papers focused on people with an agreed diagnosis, not on populations at high risk of becoming psychotic and receiving a diagnosis. A number of other reviews assessing DUP as a predictor have indicated that longer DUP is subsequently associated with poorer outcomes, including reduced adherence to CBT, Reference Álvarez-Jiménez, Gleeson, Cotton, Wade, Gee and Pearce34 altered response to antipsychotic medications, Reference Perkins, Gu, Boteva and Lieberman35 poorer social functioning Reference Barnes, Leeson, Mutsatsa, Watt, Hutton and Joyce36 and increased levels of disability. Reference Farooq, Large, Nielssen and Waheed37 There is some suggestion from studies assessing the impact of early intervention programmes on high-risk and ultra-high-risk populations that education and awareness of psychosis may significantly reduce DUP. Reference Joa, Johannessen, Auestad, Friis, McGlashan and Melle38 However, further research is needed to clarify issues surrounding DUP. Reference McGorry39

The present review focused on the first 3–5 years following the onset of illness. This period has been defined as a critical period, when many of the psychological, clinical and social deteriorations associated with psychosis might occur, Reference Birchwood, McGorry and Jackson5,Reference Lieberman and Fenton7,Reference Birchwood, Iqbal, Chadwick and Trower40 and when interventions might potentially have their greatest positive impact on prognosis. Reference Birchwood, McGorry and Jackson5,Reference Joseph and Birchwood6 Although the current evidence to support this idea is limited, intervening at the earliest possible opportunity makes both practical and ethical sense, and hope remains that such intervention might reduce subsequent symptom severity, loss of functioning and other negative consequences of psychosis such as social exclusion. Reference Thornicroft41 Intervening early may also help to reduce the adverse social and societal consequences of the disorder for both individuals and their family and carers. However, it can also be argued that providing excellent care and access to a range of appropriate and effective psychological, pharmacological and vocational interventions should be available at any stage of psychosis. Reference Kuipers42,Reference van Os and Kapur43

Implications

On balance, the evidence reviewed here suggests that early intervention services are an effective way of delivering care for people with early psychosis and can reduce hospital admission, relapse rates and symptom severity, while improving access to and engagement with a range of treatments. The characteristics of these early intervention services include the provision of multigmodal psychosocial interventions, pharmacotherapy, and some form of case management with lower case-loads and an assertive approach to treatment, all within the context of intervening as early as possible. Our review also suggests that providing evidence-based psychological interventions as part of a comprehensive early intervention service may contribute to improving outcomes for people with early psychosis. It is important that these psychological interventions have been shown rather more robustly to be effective for people with established schizophrenia. This raises the possibility that comprehensive services comparable to those described here as early intervention services, which include a full range of evidence-based psychological interventions, should be considered for people with established psychosis.

Acknowledgements

We thank other members of the Guideline Development Group of the updated edition of the schizophrenia guideline and Ms Sarah Stockton for creating the search strategies and conducting the database searches. We also thank Dr Adegboyega Sapara for independently extracting the data for the CBT section of the review.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.