Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a highly prevalent mental disorder that is associated with a high socioeconomic burden.Reference Laurenssen, Smits, Bales, Feenstra, Eeren and Noom1 Psychotherapy is the treatment of choice for patients with BPD.2–4 Mentalisation-based treatment (MBT),Reference Bateman and Fonagy5 is one of the empirically validated psychotherapies for BPD. MBT is based on the assumption that key features of BPD, such as impulsivity, affect dysregulation and problems in interpersonal relationships are related to impairments in mentalising, that is, the ability to understand the actions of other people and oneself in terms of mental states (for example needs, thoughts, feelings, wishes and desires).Reference Bateman and Fonagy5 The main goal of MBT is to help patients develop robust mentalising skills within everyday interpersonal interactions, to improve affect regulation and interpersonal functioning.

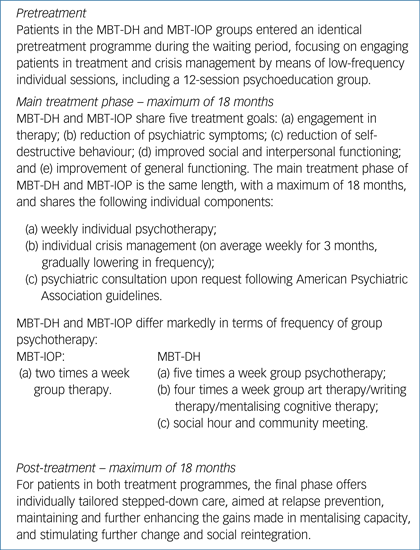

Two types of MBT for BPD have been developed and evaluated in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and naturalistic outcome studies: day hospital MBT (MBT-DH)Reference Bateman and Fonagy6–Reference Bales, van Beek, Smits, Willemsen, Busschbach and Verheul10 and intensive out-patient MBT (MBT-IOP).Reference Bateman and Fonagy11–Reference Kvarstein, Pedersen, Urnes, Hummelen, Wilberg and Karterud14 MBT-DH and MBT-IOP are identical in length (with a maximum duration of 18 months) and consist of the same number of individual treatment sessions, but they differ markedly in the frequency of group psychotherapy (Appendix). Given the large differences in the intensity and thus costs of the two treatment programmes, there is an urgent need for studies directly comparing them. A direct head-to-head comparison of MBT-DH and MBT-IOP has not yet been conducted. The current study was designed to fill this gap. We present treatment outcome results 18 months after start of treatment for a multicentre RCT comparing MBT-DH and MBT-IOP in patients with BPD (Nederlands Trial Register: NTR2292). We hypothesised that patients in both treatment programmes would show significant improvements on primary and secondary outcomes. Because of its greater treatment intensity, MBT-DH was expected to be superior to MBT-IOP (defined in terms of a between-group difference of Cohen's d ≥ 0.5) on the primary outcome of symptom severity at 18 months as measured with the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI).Reference Bateman and Fonagy5, Reference Derogatis16 Secondary outcomes included measures of borderline symptomatology, personality functioning, interpersonal functioning, quality of life and self-harm.

Method

This study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands (NL38571.078.12). The design of the study has been described in detail elsewhere.Reference Laurenssen, Smits, Bales, Feenstra, Eeren and Noom1 Inclusion criteria were (a) BPD diagnosis, (b) age ≥18 years, (c) adequate mastery of the Dutch language, and (d) travel time to the MBT ward of <1 h.

Exclusion criteria were (a) a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, chronic psychotic disorder or organic brain disorder that interferes significantly with the ability to mentalise; (b) intellectual disability (IQ < 80); or (c) a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder with a history of physical violence.

Because of ethical considerations, patients who had a stable job for at least 2 years for a minimum of 15 h a week and/or were primary caregivers of children under 4 years of age could agree to either be randomised into the study or enter MBT-IOP directly, in which case they were excluded from the trial. After providing written informed consent, patients were assessed for symptom and personality disorders using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I and Axis II disorders (SCID-I, SCID-II)Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams17, Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams and Benjamin18 administered by trained MSc-level psychologists. Patients who were excluded or refused to participate in the trial were ideally referred to an alternative evidence-based treatment delivered within the participating sites. Participating patients were then randomly allocated to either MBT-DH or MBT-IOP by an independent researcher, based on a 1:1 computerised randomisation algorithm. However, because of insufficient capacity to provide alternative treatments within the treatment sites, patients who refused participation in the trial had to be allocated to MBT-IOP more often than anticipated. This consumed part of the IOP trial capacity and we subsequently decided to adjust the randomisation algorithm in agreement with the trial steering committee, taking into account available treatment places to prevent ethically unacceptable long waiting periods while assuring random allocation. Yet, this still resulted in a skewed randomisation between the treatments. However, the average waiting period before starting both treatments was 4.3 months (s.d. = 2.4 months), and was not significantly different between the two treatment groups.

Two sites that had originally intended to participate in the trial were excluded because they were unable to implement MBT in a timely fashion, resulting in the recruitment of patients at three treatment sites (de Viersprong Amsterdam, de Viersprong Bergen op Zoom and the Netherlands Psychoanalytic Institute). Recruited patients completed an assessment battery before randomisation, at the start of treatment and at 6-month intervals up to 36 months after the start of treatment.

Treatment interventions

MBT focuses on improving capacity for mentalising in patients with BPD.Reference Bateman and Fonagy19 Mentalising is thought to play a key role in affect regulation and interpersonal relationships.Reference Bateman and Fonagy5, Reference Bateman and Fonagy20, Reference Bateman, Bales and Hutsebaut21 Treatment components and features in MBT-DH and MBT-IOP are generally very similar (Appendix), but the intensity of group therapy differs markedly: MBT-IOP involves two group therapy sessions per week, whereas MBT-DH entails a day hospital programme 5 days per week, with nine group therapy sessions per week.

Both MBT-DH and MBT-IOP were offered by therapists who had completed MBT training and received ongoing supervision in MBT. The three participating treatment sites had also successfully implemented MBT following criteria set out in the MBT quality manual,Reference Bateman, Bales and Hutsebaut21 including monitoring of adherence in daily practice by means of internal and external team supervision. To assess within-session adherence to the model, three trained raters independently rated 20 randomly sampled taped treatment sessions (stratified for condition, setting and treatment duration) using the MBT Adherence Scale.Reference Bateman and Fonagy22 Interrater reliability across the 20 tapes was high, with an average intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.87–0.99 for the subdomains and 0.94 for the total adherence score. Only one session was rated as ‘non-adherent’ to the MBT model. The average total adherence score was 3.0 (s.d. = 1.2) on a scale ranging from −3 to 9. Of all sessions, 42% were rated as ‘above adequate MBT’, represented by a total score >3.5. No significant differences were found between conditions and treatment sites in terms of adherence.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was symptom severity as assessed by the Global Severity Index (GSI) of the BSI.Reference De Beurs15, Reference Derogatis16 Secondary outcomes included (a) severity of borderline symptoms as measured with the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI-BOR);Reference Distel, De Moor and Boomsma23 (b) personality functioning as assessed by the Severity Indices of Personality Problems (SIPP);Reference Verheul24, Reference Verheul, Andrea, Berghout, Dolan, Busschbach and van der Kroft25 (c) interpersonal problems as measured by the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP);Reference Horowitz, Alden, Wiggins and Pincus26, Reference Zevalkink, de Heys, Hoek, Berghout, Brouwer and Riksen-Walraven27 (d) quality of life as assessed by the Dutch-language version of the EuroQol (EQ-5D);Reference Brooks, Rabin and de Charro28 and (e) frequency of suicide attempts and self-harm as assessed by the Suicide and Self-Harm Inventory (SSHI).Reference Bateman and Fonagy19

The a priori power analysis was based on the GSI. With n = 45 patients in each treatment arm, a superiority margin of d ≥ 0.50 could be detected with one-sided testing, α = 0.05 and 0.80 power.Reference Laurenssen, Smits, Bales, Feenstra, Eeren and Noom1

Statistical analyses

Differences in demographic and clinical features at baseline were investigated using two-tailed chi-square tests and independent sample t-tests, as appropriate. Treatment outcomes were examined over time using multilevel modelling in order to deal with the dependency of repeated measures within participants over time and missing data in longitudinal follow-up using the XTMIXED procedure of Stata Statistical Software Release 12.

All outcome analyses were based on intention-to-treat principles. Time points were coded −3, −2, −1 and 0, implying that regression coefficients involving time measured the rate of change from baseline to 18 months after start of treatment and regression intercepts referenced group differences at the last time point. SSHI scores were log-transformed as they were highly positively skewed. Maximum likelihood was used to assess whether random or fixed slopes should be assumed in models for each outcome variable. Subsequently, quadratic and cubic time variables were added to the model if likelihood ratio tests showed significant improvement in fit. Estimates and Cohen's d effect sizesReference Cohen29 are based on predicted values.

There was a substantial proportion of missing data (range 12–52%), which was evenly distributed across the conditions. Although multilevel modelling is quite robust in dealing with missing data, we re-ran all analyses using state-of the-art data imputation procedures. Missing values were imputed using the multiple imputation software Amelia-2 (for R version 3.2.1+) in ten data-sets. These ten imputed data-sets were combined using Rubin's rules for combining estimates obtained from multiple imputed data-sets.Reference Rubin30 Because estimated trajectories of change and effect sizes were highly similar for the imputed and non-imputed data, results based on the non-imputed data-set are reported. Results of the imputed data are available upon request from the author.

Results

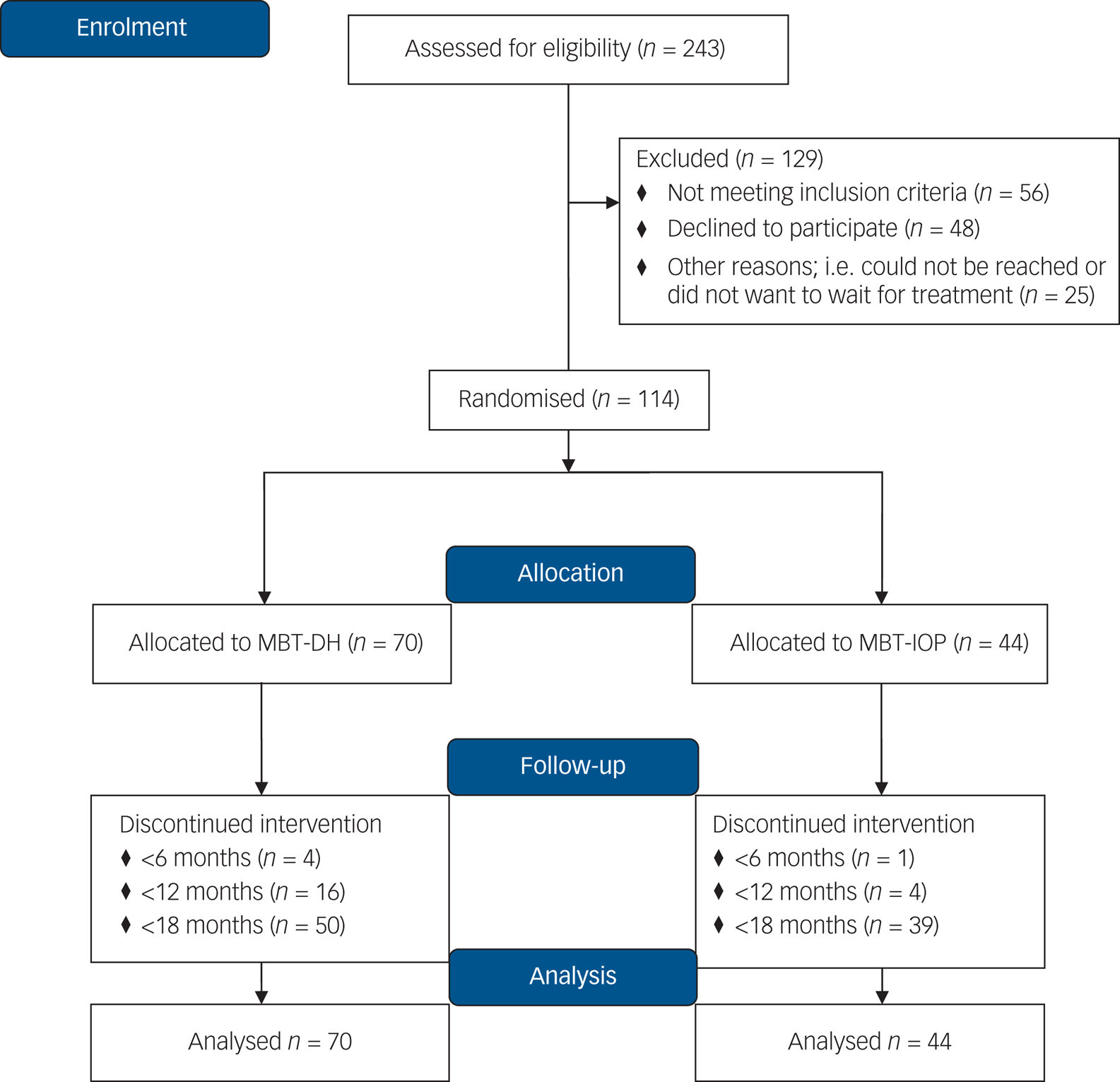

Between March 2009 and June 2014, 243 patients were referred to MBT in the participating treatment centres, of whom 114 met inclusion criteria and were randomised (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 CONSORT flow diagram.

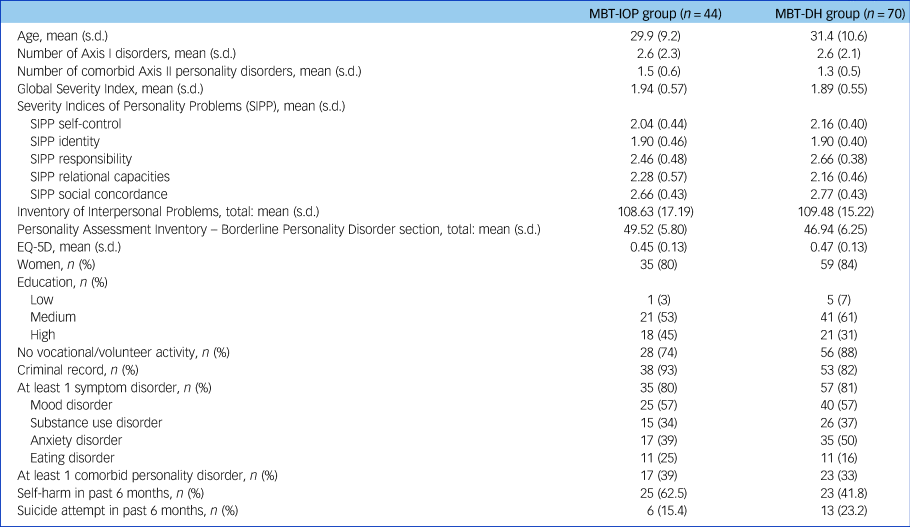

Table 1 shows demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline. There were no significant baseline differences between patients who were excluded and patients who were randomised. Treatment groups did not show any significant differences at baseline, except for self-harm. A greater number of patients assigned to MBT-IOP reported self-harm in the previous 6 months (χ2(1) = 3.96, P < 0.001), although there was no significant difference in reported frequency. Average treatment duration was slightly, although significantly, shorter in MBT-DH (mean 14.3 months, s.d. = 4.2) compared with MBT-IOP (mean 15.9 months, s.d. = 3.1), t(109) = 2.223, P = 0.028. The overall drop-out rate was 12% (n = 14), with no differences between the groups (n = 5, 11% for MBT-IOP and n = 9, 13% for MBT-DH), χ2(1) = 0.056, P = 0.813.

Table 1 Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with borderline personality disorder in intensive outpatient mentalisation-based treatment (MBT-IOP) or day hospital mentalisation-based treatment (MBT-DH)a

a. Baseline estimates based on predicted values. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics on education, vocational or volunteer activity, criminal record, self-harm and suicide attempts were not available for n = 114 due to missing data.

Primary outcome

Improvement over time between baseline and 18 months after start of treatment was significant, representing large effect sizes, in both MBT-IOP (d = 0.83) and MBT-DH (d = 1.16). There was no evidence for a differential rate of change between the two groups (β = −0.06, 95% CI −0.19 to 0.07, z = −0.88, P = 0.377). The between-group effect size of Cohen's d = 0.34 indicated that MBT-DH was not superior to MBT-IOP in terms of improvements in symptom severity based on the a priori specified Cohen's d ≥ 0.5 margin (Table 2).

Table 2 Predicted means and results from multilevel models on primary outcome measure symptom severity for patients randomly assigned to intensive out-patient mentalisation-based treatment (MBT-IOP) (n = 44) or day hospital mentalisation-based treatment (MBT-DH) (n = 70)a

GSI, Global Severity Index of the Brief Symptom Inventory; d.f., degrees of freedom.

a. See supplementary Table 1 for a version of this table that also includes data for secondary outcomes.

** P < 0.01.

Secondary outcomes

Significant improvements were observed on all secondary outcome measures 18 months after start of treatment, representing moderate to very large within-group effect sizes for both MBT-DH and MBT-IOP (see supplementary Table 1, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.9). For most secondary outcome measures, the differential rate of change between MBT-DH and MBT-IOP was not significant, with two exceptions, both in the domain of relational functioning. The differential rate of change was significantly larger for MBT-DH relational capacities as measured with the SIPP (β = 0.12, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.22, z = 2.26, P = 0.024) and there was a similar trend for interpersonal problems as measured by the IIP (β = −7.40, 95% CI −14.93 to 0.13, z = −1.93, P = 0.056).

On secondary outcomes, between-group effect sizes consistently favoured MBT-DH, with multiple secondary outcome measures indicating MBT-DH to be superior to MBT-IOP at 18 months, defined as between-group differences ≥0.5. This was also the case on the PAI-BOR, which assesses core features of borderline pathology. However, both treatment groups showed similar improvements in terms of suicide attempts and self-harm, with medium to large effect sizes.

Discussion

Main findings

This is the first study to compare the efficacy of two intensities of MBT for patients with BPD. Both treatment groups showed major improvements on primary and secondary outcome measures 18 months after start of treatment. Within-group effect sizes were for the most part large to very large and comparable with those found in other studies of MBT.Reference Bateman and Fonagy6, Reference Bales, Timman, Andrea, Busschbach, Verheul and Kamphuis9–Reference Bateman and Fonagy11, Reference Jørgensen, Bøye, Boye, Jordet, Andersen and Kjolbye13, Reference Kvarstein, Pedersen, Urnes, Hummelen, Wilberg and Karterud14 Treatment drop-out was relatively low (mean 12%, n = 14) compared with that reported in other RCTs of specialised BPD treatments.Reference Barnicot, Katsakou, Marougka and Priebe31 Contrary to our hypothesis, MBT-DH was not superior to MBT-IOP in terms of reductions in symptom severity. However, MBT-DH showed a tendency towards superiority on most secondary outcomes, with medium to large within-group effect sizes (range d = 0.51–1.82).

Interpretation of our findings

Importantly, although patients in both MBT-DH and MBT-IOP showed large improvements in core features of BPD, there was a clear trend for MBT-DH to be associated with greater changes in BPD features. Yet, between-group differences were most pronounced in the domain of relational functioning, with patients in MBT-DH showing large improvements, whereas patients in MBT-IOP showed limited improvements over the course of 18 months. This latter finding may perhaps be in part explained by the greater availability of the ‘safety net’ provided by the day hospital setting of MBT-DH. Patients in MBT-DH might have had more opportunities to experiment with new (interpersonal) behaviours within a relatively safe context, whereas patients in MBT-IOP were forced to experiment with new interpersonal behaviours mainly in their own personal environment, which may not yet provide the safe context that would assist successful generalisation of therapeutic gains.

These views are consistent with recent conceptualisations of therapeutic change in patients with BPD,Reference Fonagy, Luyten and Allison32 emphasising the need for patients with BPD to generalise what they have learned in treatment to the real world outside the treatment context. However, patients in MBT-DH may begin to struggle with the same interpersonal problems as patients in MBT-IOP after the end of their treatment, when their ‘safety net’ has largely disappeared. Thus, longer-term follow-up is imperative to provide more accurate estimates of sustained change in both types of treatment. In addition, further exploration of the mechanisms of change in both treatment conditions would serve to shed more light on these assumptions. Future reports will focus on these issues.

Irrespective of the fact that there was no clear evidence for the superiority of MBT-DH 18 months after the start of treatment and irrespective of whether or not there is evidence for the superiority of MBT-DH at longer-term follow-up, the current findings suggest that patients in MBT-DH and MBT-IOP follow different trajectories of change, which may be important not only for patients but also for clinical decision-making.

Limitations

There are a number of important limitations of this study that should be kept in mind when interpreting the results. First, the choice of symptom severity as our primary outcome measure was based upon the need to facilitate future comparison with treatment outcome in clinical practice by using a simple and widely used outcome measure. However, the BSI might not capture key BPD features. Therefore, we also included more specific BPD measures as secondary outcomes, including the PAI-BOR, the IIP and SIPP. Note, however, that the BSI was highly significantly correlated with the PAI-BOR in the current study (r = 0.73, P < 0.01).

Second, although both MBT programmes were offered by certified therapists, treatment sites were monitored for adherence to MBT quality guidelines and within-session adherence in individual therapy was monitored, important features of adherence to MBT (i.e. continuous adherence to the model at the level of programme organisation and in group therapy) were not systematically measured in this study. The potential influence of these factors was somewhat mitigated, however, by the finding that there were no differences in within-session adherence between MBT-DH and MBT-IOP and both treatments were offered by the same treatment services.

Third, there was a considerable percentage of missing data in the study, particularly at follow-up assessments. However, the multiple imputation analyses yielded comparable results. Fourth, the superiority margin set in this study corresponded to a medium effect size. Smaller between-group differences may be clinically relevant, and thus further research is needed to address this issue. Fifth, the tendency of MBT-DH to be superior on secondary outcomes might reflect chance findings, particularly as there were no differences in terms of self-destructive behaviour. Findings of this study therefore need to be replicated, and longer-term follow-up is needed to investigate whether these differences are maintained in the longer term.

Sixth, it cannot be ruled out that pharmacotherapy might have contributed to the observed improvements, as medication use over the course of treatment was not included in the analyses. However, there were no differences between the conditions in terms of the percentage of patients using medication at baseline and during treatment. Finally, randomisation to the two conditions was skewed. However, there were no baseline differences between the two groups, with the exception of slightly higher levels of self-reported self-harm in the MBT-IOP group.

Implications

In conclusion, this study suggests that treatment intensity may have an effect on treatment outcomes in a specialised psychological treatment for patients with BPD at least 18 months after the start of treatment and in particular domains of functioning. This finding is important given the increasing financial pressure to develop less intensive treatments and the gradual discontinuation of high-intensity programmes in clinical practice. The current findings suggest that such a policy may be premature, as there was a tendency for MBT-DH – the more intensive treatment – to be more effective than MBT-IOP on a range of secondary outcomes. Ultimately, longer-term follow-up and considerations concerning the cost-effectiveness of both treatments may be key in determining the optimal intensity of specialised treatments for patients with BPD, such as MBT. This will be addressed in future studies.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.9.

Funding

This research was supported in part by a grant from ZonMw (grant no. 171202012).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all research assistants for collecting the data. We are also grateful to the patients who participated in this study.

Appendix

Comparison of intensive outpatient mentalisation-based treatment (MBT-IOP) and day hospital mentalisation-based treatment (MBT-DH)

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.