Cluster B personality disorders, including borderline, antisocial, histrionic and narcissistic, are among the most prevalent mental disorders in the general population Reference Torgersen, Kringlen and Cramer1,Reference Lenzenweger, Loranger, Korfine and Neff2 and in mental healthcare settings. Reference Zimmerman, Rothschild and Chelminski3,Reference Zimmerman, Chelminski and Young4 Moreover, these disorders are associated with high societal costs and a low quality of life. Reference Soeteman, Hakkaart-van Roijen, Verheul and Busschbach5,Reference Soeteman, Verheul and Busschbach6 Although different in many respects, a common feature of cluster B personality disorders is a rather dramatic and impulsive manifestation that is considered more persistent and resistant to change than cluster C personality disorders (i.e. avoidant, dependent and obsessive–compulsive) but less so than cluster A personality disorders (i.e. paranoid, schizoid and schizotypal). Currently, several treatments with demonstrated efficacy for borderline personality disorders are being adapted and tested for antisocial personality disorders, suggesting a partially common nature to these disorders. Reference Bateman and Fonagy7 Additionally, contemporary classification models of personality disorders increasingly focus on dimensions rather than categories, and cluster B personality disorders seem to have similarly high scores on dimensions of behavioural and emotional disinhibition and antagonism. Reference Saulsman and Page8 This paradigm shift makes it clinically relevant to include the full range of cluster B personality disorders in analyses rather than focusing solely on the more common borderline personality disorders.

A multidisciplinary clinical guideline in The Netherlands recently identified various modalities of psychotherapy, including out-patient, day hospital, and in-patient psychotherapy, to be preferential for cluster B personality disorders, 9 consistent with two other clinical guidelines that focused on borderline personality disorders. 10,11 Although based on strong evidence of efficacy, Reference Verheul and Herbrink12 the economic impact of these recommendations has not yet been explored and few cost-effectiveness analyses of personality disorder interventions exist that can guide decision-making with respect to clinical practices and healthcare resource allocation. Recently, the Study on Cost-Effectiveness of Personality disorder Treatment (SCEPTRE) was conducted with the purpose of providing data for economic evaluation of various psychotherapeutic treatments for personality disorders. Used in a decision-analytic framework, the data on health benefits and resource use from this study can be synthesised to evaluate the relative performance of health interventions under conditions of uncertainty and imperfect data. Reference Briggs, Sculpher and Claxton13 The objective of this study was to assess the cost-effectiveness of three modalities of psychotherapy in treating cluster B personality disorders (i.e. out-patient, day hospital and in-patient psychotherapy) and to inform decision makers about the value of these treatment options. We incorporated clinical and economic patient-level data from the SCEPTRE trial in a simulation model to compare the strategies over a 5-year time horizon in terms of costs per recovered patient-year and costs per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

Method

Model

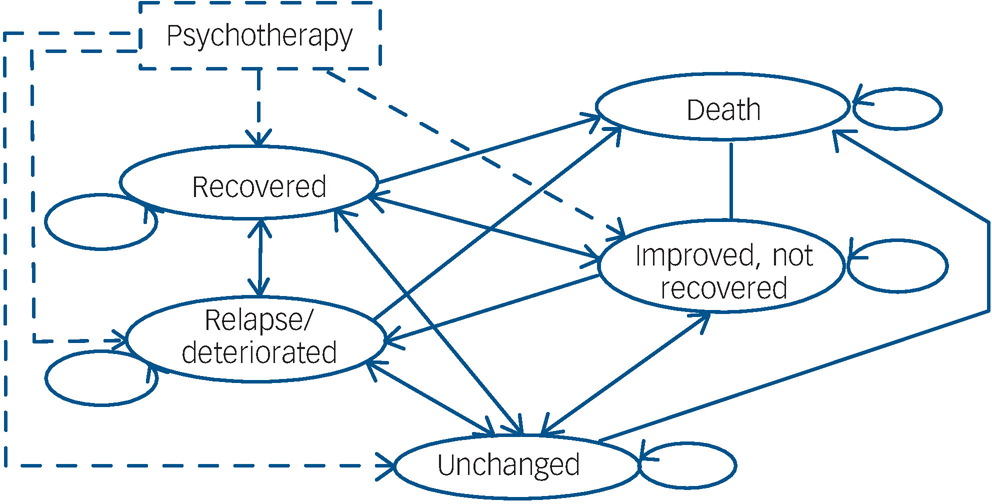

We used a previously developed Markov cohort model Reference Briggs, Sculpher and Claxton13,Reference Soeteman, Verheul, Meerman, Ziegler, Rossum and Delimon14 to simulate the transition of a cohort of individuals with cluster B personality disorders through mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive health states over time, based on data from the SCEPTRE trial. The model is then used to estimate the impact of different interventions on the patient population. The underlying clinical process driving the current model and by which the health states are defined is ‘clinically significant change’, based on a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Reference Jacobson and Truax15 To calculate the cut-off points and the reliable change index required for this approach, norm scores based on the Symptom Checklist–90 Revised (SCL–90–R) were used as treatment outcome measures for both the functional and the dysfunctional population. Reference Derogatis16 Patients are classified into one of four health states: recovered (if the magnitude of change is statistically reliable and the individual ends up within normal limits on the variable of interest); improved (if the individual shows statistically reliable change but ends therapy still somewhat dysfunctional); unchanged (if the magnitude of change is not statistically reliable, the method cannot determine whether or not the change is clinically significant); and relapsed or deteriorated (if a statistically reliable change is in the opposite direction to that indicative of improvement). At anytime, patients can also die from suicide or age-specific background mortality. The structure of the Markov model is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 State transition diagram of the Markov model for psychotherapy.

Four types of parameters were used in the model: transition probabilities, which govern the movement between the five states at each cycle; treatment costs of the three modalities of psychotherapy; costs of healthcare utilisation and productivity losses incurred by patients in each state; and health state utilities, which reflect the health-related quality of life experienced by individuals in each state. These data were obtained from a single patient-level data source (i.e. the SCEPTRE trial), a non-randomised clinical trial. Strengths and limitations of the study design have been discussed elsewhere. Reference Drummond, Sculpher, Torrance, O'Brien and Stoddart17,Reference Glick, Doshi, Sonnad and Polsky18 To overcome the problem of selection bias we controlled for initial differences in patient characteristics with the propensity score method (see p. ). The results are based on intention-to-treat analyses.

Transitions between health states in the model were assumed to occur at a constant interval of every 6 months, corresponding to multiple changes in pathology, symptoms, treatment decisions or costs for patients with personality disorders.

To be consistent with many other trial-based economic evaluations in the literature, we chose a 5-year time horizon, which is 2 years beyond the duration of the clinical trial. With respect to the transition probabilities, we extrapolated for the last 2 years of the analysis and considered several methods of extrapolation. Based on the trends observed during the study, we elected to average the last two observations (i.e. years 2 and 3) from the trial and hold those values constant in years 4 and 5 of the analysis. For other model inputs, data collection did not stop at 3 years; indeed, we relied on questionnaires that were administered in the fourth year to estimate the costs and utilities associated with different health states and kept these values constant for the fifth year. We reported results as costs per recovered patient-year and costs per QALY over the 5 years using the model; costs and QALYs were discounted at an annual rate of 4.0% and 1.5% respectively, consistent with guidelines for economic evaluations in The Netherlands. 19 In a sensitivity analysis, we studied the impact of applying a 3% discount rate for both costs and health outcomes as recommended by UK and US economic guidelines. The base case analysis was conducted from the societal perspective, and a secondary analysis from the payer perspective.

Recruitment and assignment

Individuals were recruited from a consecutive series of admissions to six mental healthcare institutes in The Netherlands offering specialised psychotherapy for adults with personality disorders. Diagnoses were based on the Dutch version Reference De Jong, Derks, Van Oel and Rinne20 of the Structured Interview for DSM–IV Personality (SIDP–IV). Reference Pfohl, Blum and Zimmerman21 For this particular analysis, inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of cluster B personality disorders, age 18–70 years, assignment to a specified dosage of psychotherapeutic treatment for personality disorders, and Dutch literacy. Exclusion criteria were psychotic disorders (e.g. schizophrenia), organic cerebral impairment and mental retardation. Comorbid Axis I and Axis II disorders were allowed.

From March 2003 to March 2006, 1379 individuals completed the intake procedure and were selected for various treatment options. Of those, 241 individuals were eligible, provided informed consent and entered the study (Table 1). Participants were assigned to one of three treatment groups, based on a comprehensive assessment battery combined with the expert opinion of clinicians: out-patient, day hospital and in-patient psychotherapy. In the out-patient strategy, individuals are offered up to two sessions per week. In the day hospital strategy, individuals are offered psychotherapy combined with sociotherapy and/or non-verbal therapies for 1–5 days per week. The in-patient strategy offers the same but individuals reside in the treatment centres 5–7 days per week. Mean duration of treatment for these three strategies was 15.1 (s.d. = 7.1), 10.4 (s.d. = 4.7) and 9.3 (s.d. = 2.9) months respectively.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical charactersistics of 241 study participants

| Characteristics | Out-patient (n = 57) | Day hospital (n = 99) | In-patient (n = 85) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 35.4 (8.7) | 31.4 (8.2) | 28.9 (7.2) |

| Female, % | 64.9 | 76.8 | 70.6 |

| Comorbidity Axis II, % | |||

| Pure cluster B | |||

| (no comorbid cluster A/C) | 33.3 | 37.4 | 48.2 |

| Cluster B and cluster C | 8.8 | 0 | 3.5 |

| Cluster B and cluster A | 49.1 | 45.5 | 40.0 |

| Cluster B and both cluster A and C | 8.8 | 17.2 | 8.2 |

| Personality disorder, % | |||

| Borderline | 71.9 | 80.8 | 80.0 |

| Narcissistic | 29.8 | 22.2 | 18.8 |

| Histrionic | 19.3 | 9.1 | 14.1 |

| Antisocial | 8.8 | 5.1 | 3.5 |

Input data

Transition probabilities

The proportion of participants in each of the health states was determined at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months after baseline from the SCEPTRE trial. Based on the difference between the frequency distributions over time, the probabilities of transitioning from one state to another in each 6-month time period were calculated (transition probabilities among the recovered, improved, unchanged and relapsed or deteriorated health states are available from the author on request).

Costs

Costs were estimated from both societal and payer perspectives. The calculations from the societal perspective included direct medical costs (i.e. primary treatment costs and costs of healthcare utilisation post-discharge) and direct non-medical costs (i.e. lost productivity due to time spent in treatment), as well as indirect costs (i.e. future lost productivity due to disease), whereas the payer perspective included only direct medical costs. Mean primary treatment costs for the three strategies were calculated by multiplying the resource quantities with the 2007 unit costs or prices of the corresponding treatment options. We obtained data from the hospital finance departments on staff salaries, equipment, buildings and departmental overheads, and used a micro-costing approach to derive the cost of a treatment session and an in-patient day. The resource quantities were collected from the hospital data systems. Costs due to productivity loss because of patients' time in treatment were also estimated and included in the analysis from the societal perspective. For participants with paid employment at enrolment, mean costs were calculated by multiplying the actual days (in-patient psychotherapy, day hospital psychotherapy) and hours (out-patient psychotherapy) spent in treatment by the net income of the participant per day and per hour respectively. The mean treatment costs were €7445 (s.e. = 511) for out-patient psychotherapy, €23 279 (s.e. = 1738) for day hospital psychotherapy, and €35 218 (s.e. = 1354) for in-patient psychotherapy.

Post-discharge costs due to healthcare utilisation and productivity losses, which were likely to be substantial, were also included. The Trimbos and Institute for Medical Technology Assessment (iMTA) Questionnaire on Costs Associated with Psychiatric Illness (TiC-P) was used to collect data on direct medical and indirect costs. Reference Hakkaart-van Roijen22 For direct medical costs, the total number of medical visits (e.g. out-patient visits, hospital lengths of stay, use of medication) was multiplied by the 2003 unit prices of the corresponding healthcare services. Reference Oostenbrink, Bouwmans, Koopmanschap and Rutten23,24 The reference unit prices of healthcare services for 2003 were adjusted to prices in 2007 using the consumer price index. 25 The mean direct medical costs over the recall period of the TiC-P (i.e. 4 weeks) were multiplied by 6.5 to calculate the 6-month costs to correspond to the model cycle length. For indirect costs, we obtained data on absence from work, reduced efficiency at work, and difficulties with job performance from the TiC-P short form of the Health and Labor Questionnaire. Reference Roijen, Essink-Bot, Koopmanschap, Bonsel and Rutten26 The days of short-term absence from work and actual hours missed at work because of health-related problems were multiplied by the net income of the participant per day and per hour respectively. The number of lost working days per participant was calculated, taking into account the number of days and hours of paid employment of the participant per week. To value long-term absence from work, we applied the friction-cost method, which takes into account the fact that a formerly unemployed person may replace a person who becomes disabled. Reference Koopmanschap and Rutten27 The period needed to replace a worker (the so-called friction period) is estimated to be 5 months; we therefore assumed the maximum indirect costs to society were limited to productivity losses during a period of 5 months. The cost estimates from the societal perspective used in the analysis are summarised in Table 2. For each strategy, the model calculates the expected cost by taking a weighted average of the costs of each health state and the proportion of the cohort in each health state at each 6-month period; the total expected cost of the strategy is then calculated by summing over the 5-year time horizon.

Table 2 Model parameters: mean health state costs and utilities over time from the societal perspective

| Recovered | Improveda | Unchanged | Relapsed or deteriorated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health state costs, €:b mean (s.e) | ||||

| 1-2 years | 6637 (3 064) | 9639 (4 848) | 10 846 (3 763) | 24 481 (13 204) |

| 3 years | 2472 (458) | 3899 (1 013) | 5705 (1 533) | 5554 (2 312) |

| 4-5 years | 2188 (491) | 11 395 (8 215)c | 4751 (1 297) | 5767 (2 830) |

| Health utilities,d mean (s.e.) | ||||

| 1 year | 0.78 (0.03) | 0.64 (0.11) | 0.67 (0.06) | 0.39 (0.10) |

| 2 years | 0.82 (0.02) | 0.65 (0.03) | 0.59 (0.03) | 0.47 (0.07) |

| 3 years | 0.83 (0.02) | 0.58 (0.05) | 0.60 (0.04) | 0.45 (0.18) |

| 4-5 years | 0.87 (0.02) | 0.67 (0.04) | 0.69 (0.03) | 0.34 (0.15) |

Health utilities

To reflect the diminished quality of life of people with personality disorders, health utility weights were assigned to each health state, based on the EuroQol EQ–5D which records quality of life in five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Reference Brooks, Rabin and de Charro28 Each dimension is divided into three response levels: no problems, some or moderate problems and extreme problems or complete inability. A total of 243 different possible health states are each weighted to derive a single index score between –0.33 (worst imaginable health state) and 1.00 (best imaginable health state). The Dutch norm scores were used for calculating the mean EQ–5D index values. Reference Lamers, Stalmeier, McDonnell, Krabbe and Busschbach29 The mean quality of life utilities of a year spent in each of the model health states for each cycle are summarised in Table 2. The expected number of QALYs for each strategy was estimated by weighing the duration of time in a particular health state by the utility of that health state and then summing over all health states in each cycle. The expected number of QALYs per patient over 5 years was calculated by summing over all cycles.

Mortality rates

Participants in the recovered health state were assumed to face a risk of death equivalent to that observed in the general population. These age- and gender-specific mortality rates were obtained from standard life tables. 30 Moreover, we assumed participants in the improved, unchanged and relapsed or deteriorated health states faced an elevated risk of death due to suicide, based on the SCEPTRE data.

Propensity score method

To overcome the problem of selection bias, we controlled for initial differences in patient characteristics with the multiple propensity score method. Reference Rosenbaum and Rubin31 The estimated propensity score is defined as the conditional probability of assignment to a particular treatment, given a set of observed pre-treatment characteristics. Details of the method and the variables used to estimate the propensity scores are described elsewhere. Reference Bartak, Spreeuwenberg, Andrea, Busschbach, Croon and Verheul32 Multinomial regression analyses were conducted to adjust the transition probabilities for the multiple propensity scores.

Analysis

In order to reflect uncertainty in our parameter values, we conducted a probabilistic analysis in which distributions were assigned to the input parameters of the model (i.e. gamma distributions for costs, beta distributions for utilities and Dirichlet distributions for probability parameters). Reference Briggs, Sculpher and Claxton13 Multiple simulations were conducted in which a single value for each parameter was randomly sampled from the corresponding distribution, creating a unique parameter set. One thousand parameter sets were sampled and used in the model to calculate the expected costs, expected recovered patient-years and QALYs for each strategy.

The mean values of costs, recovered patient-years, and QALYs across all 1000 simulations were used to calculate incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICER) associated with each strategy, defined as the additional cost divided by the additional health benefit associated with one strategy as compared with the next less costly strategy. The most cost-effective strategy was then identified by comparing the ICERs of different strategies against various threshold values, which reflect the decision maker's willingness-to-pay for an additional unit of effect. Strategies below a specific willingness-to-pay value generally represent good value for money; the ‘most cost-effective’ strategy is the strategy with the highest ICER below the willingness-to-pay threshold, representing the option that yields the highest level of benefit for an acceptable cost.

In order to report on the impact of the uncertainty in the parameter values, cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEAC) were created to indicate the probability of each option being cost-effective conditional on the decision maker's willingness-to-pay for a recovered patient-year or QALY. Reference Fenwick, Claxton and Sculpher33 Finally, the cost-effectiveness acceptability frontier (CEAF) was plotted to portray each CEAC over the range of threshold values for which each option is estimated to be the most cost-effective, as well as the threshold ICER at which there are changes in the optimal modality (i.e. ‘switch points’). Reference Barton, Briggs and Fenwick34

Results

Five-year costs and health outcomes

The mean 5-year costs and health outcomes from the societal perspective are presented in Table 3. The table shows that the mean costs are substantially lower for out-patient psychotherapy, suggesting that the higher treatment costs of the day hospital and in-patient modalities are not offset by savings elsewhere, such as reductions in costs from healthcare utilisation and productivity losses. The rank ordering of strategies by effect is the same for both recovered patient-years and QALYs, indicating in-patient psychotherapy as the most effective option. With respect to the percentage of participants residing in the recovered health state at year 5, day hospital psychotherapy is associated with the highest percentage recovered. Out-patient psychotherapy appears to be consistently the least effective option.

Table 3 Discounted costs and health outcomes over 5 years from the societal perspective

| Modality of psychotherapy | Costs,a € | Recovered patient-yearsb | Costs,a € | QALYsc | Recovered, %d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Out-patient | 78 548 | 1.1449 | 80 247 | 3.1080 | 24.7 |

| Day hospital | 89 323 | 2.0227 | 91 090 | 3.3005 | 48.6 |

| In-patient | 96 264 | 2.0840 | 97 351 | 3.3223 | 36.1 |

Cost-effectiveness analysis from the societal perspective

The cost-effectiveness ratios for each strategy, reported as cost per recovered patient-year and cost per QALY over a 5-year time horizon, are displayed in Table 4. Out-patient psychotherapy yields the lowest costs and health benefits; day hospital psychotherapy shows higher costs and effects, and was associated with an ICER of €12 274 per recovered patient-year and an ICER of €56 325 per QALY compared with out-patient psychotherapy. In-patient psychotherapy yields the highest costs and health benefits and was associated with an ICER of €113 298 per recovered patient-year and an ICER of €286 493 per QALY compared with day hospital psychotherapy.

Table 4 Cost-effectiveness from the societal perspective over a 5-year time horizona

| Modality of psychotherapy | Cost per recovered patient-year, € | Cost per QALY, € |

|---|---|---|

| Out-patient | - | - |

| Day hospital | 12 274 | 56 325 |

| In-patient | 113 298 | 286 493 |

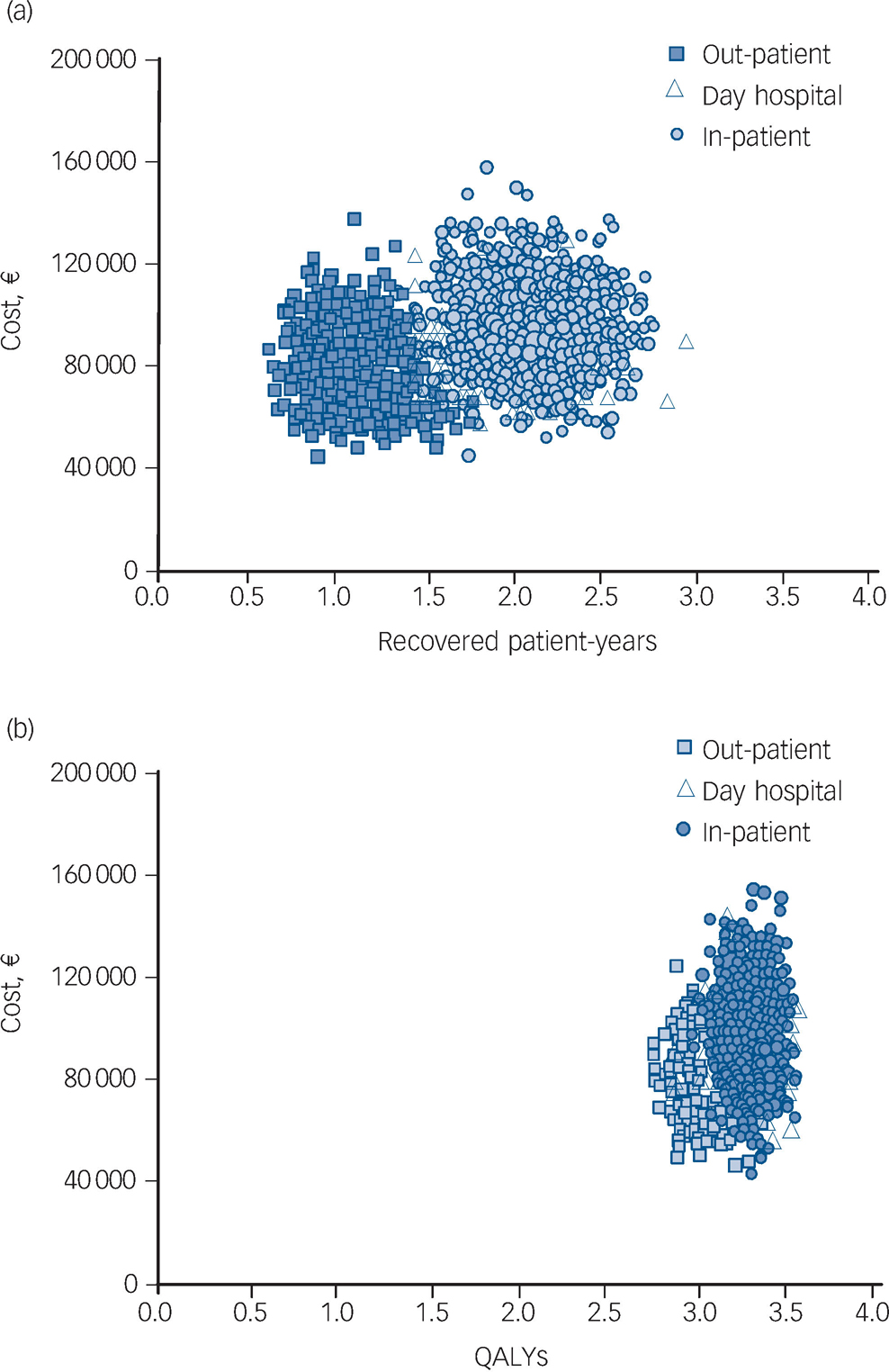

To display the impact of parameter uncertainty we plotted the relationship between cost and health outcomes for each of the three competing psychotherapy modalities over 1000 simulations in the cost-effectiveness plane (Fig. 2). When plotting costs against recovered patient-years (Fig. 2(a)), we found substantial uncertainty about both costs and effects for all treatment options. When using QALYs as the health measure (Fig. 2(b)), we found equal uncertainty about costs, whereas the uncertainty in effect was less substantial. The observed differences among the three treatment modalities relating to the effects were more pronounced in terms of recovered patient-years than QALYs.

Fig. 2 Scatter plots showing the costs and health outcomes of the treatment strategies from 1000 Monte Carlo simulations for (a) recovered patient-years and (b) for quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs).

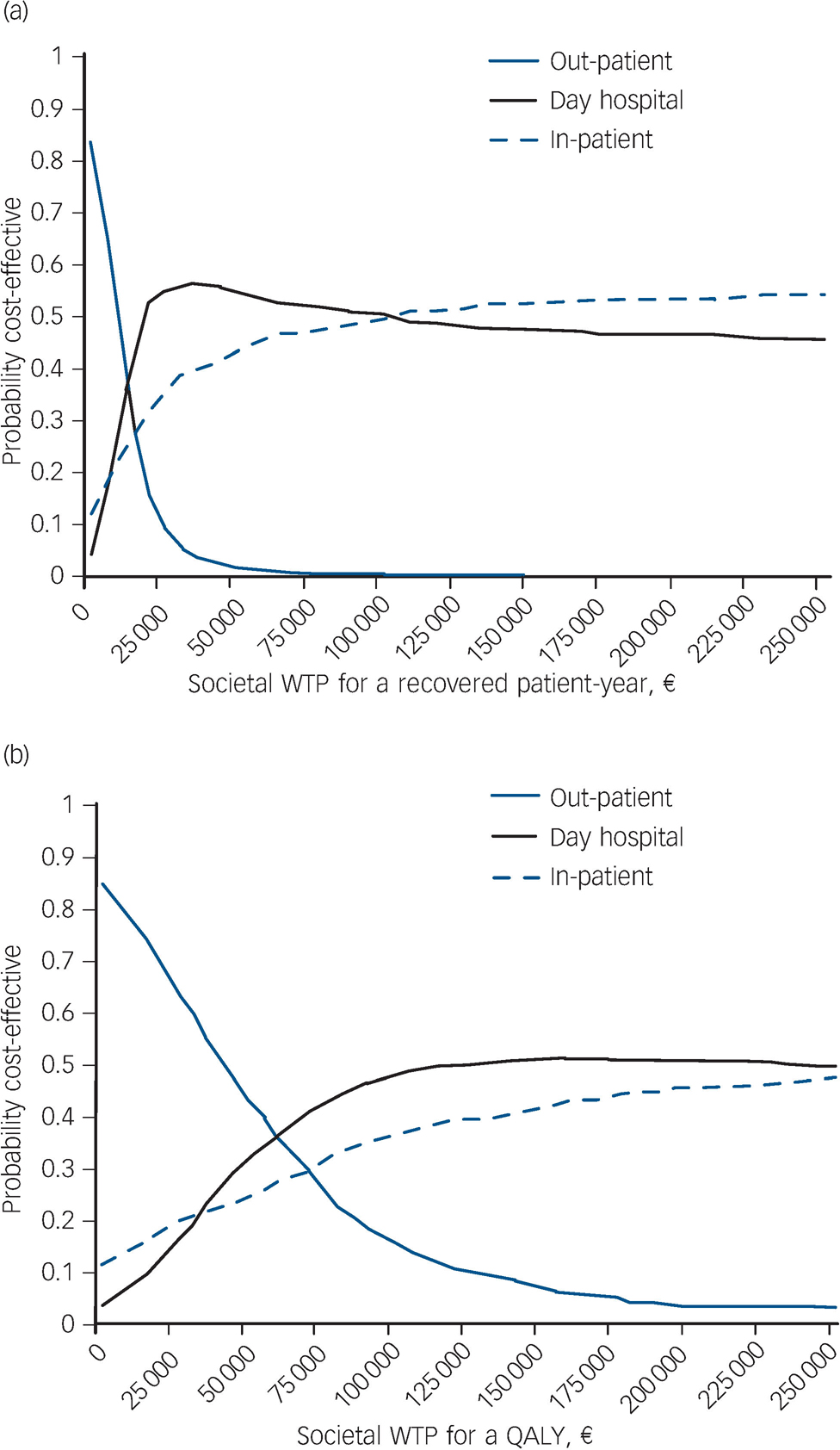

Figure 3 shows the CEAC, which indicate the probability of each strategy being cost-effective at different values of the societal willingness-to-pay for a unit of health benefit. In terms of cost per recovered patient-year (Fig. 3(a)), out-patient psychotherapy has the highest probability of being cost-effective for values of the societal willingness-to-pay below €12 500. For values between €12 500 and €103 100 per recovered patient-year, day hospital psychotherapy is likely to be the most cost-effective. For values above €103 100 per recovered patient-year, in-patient psychotherapy has the highest probability of being cost-effective. In terms of costs per QALY (Fig. 3(b)), the same pattern of results can be observed, but the switch points were located at threshold values of €59 700 and €298 000 respectively. By definition, the CEAC crosses the Y-axis at the probability that the intervention under evaluation is cost saving, as a willingness-to-pay of zero implies that only cost determines cost-effectiveness (formula: willingness-to-pay × Δ effect–Δ costs >0). Reference Fenwick, O'Brien and Briggs35 According to the current analysis, out-patient psychotherapy has a probability of being cost saving in approximately 84% of model simulations; in contrast, day hospital and in-patient psychotherapy have a negligible probability of being cost saving.

Fig. 3 Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEAC) showing the probability of each modality being cost-effective at different values of the societal willingness-to-pay (WTP). (a) CEAC for recovered patient-year; (b) CEAC for quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs).

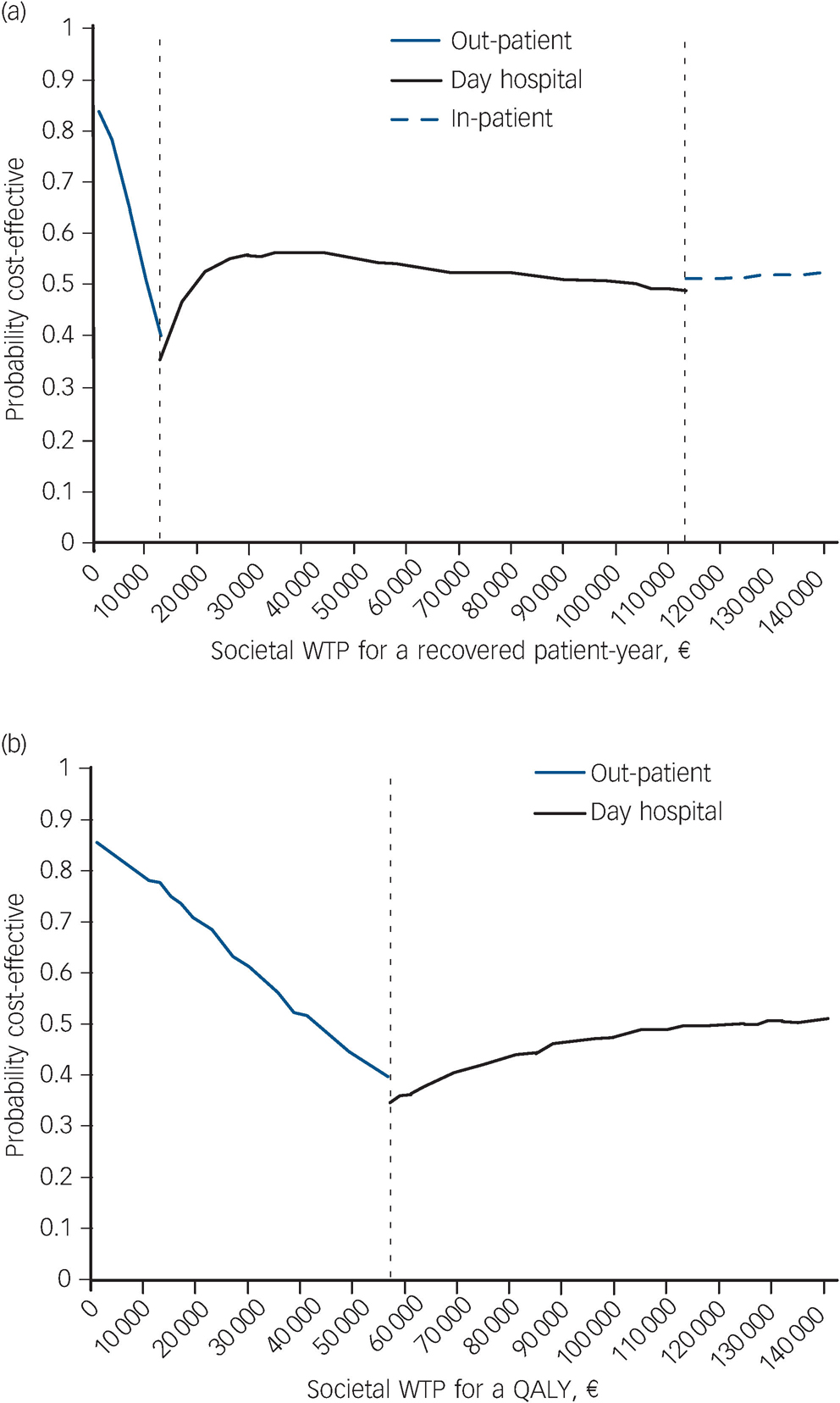

Although it is helpful to know the impact of uncertainty on results, the probability of a strategy being cost-effective is not sufficient to determine the optimal option. Decisions should be made on the basis of expected net benefit, regardless of the uncertainty associated with the decision. Reference Fenwick, Claxton and Sculpher33 To identify the optimal treatment option (i.e. the option with the highest expected net benefit for a given cost), the CEAF were plotted (Fig. 4). The CEAF of costs per recovered patient-year (Fig. 4(a)) show the range of threshold values over which out-patient psychotherapy (€0–12 274), day hospital psychotherapy (€12 274–113 298) and in-patient psychotherapy (above €113 298) have the highest expected net benefit and can be considered the optimal choice. The switch points, at which there is a change in the optimal option, correspond to the ICERs between out-patient and day hospital psychotherapy, and day hospital and in-patient psychotherapy. In terms of cost per QALY (Fig. 4(b)), the switch points were located at threshold values of €56 325 and €286 493 respectively. If society's willingness-to-pay for a QALY is below the threshold value of €56 325, out-patient psychotherapy is the most cost-effective choice; above this value (and below €286 493), the optimal strategy would be day hospital psychotherapy. When we varied the discount rate to 3% per year for both costs and health outcomes, the optimal option changed from out-patient psychotherapy to day hospital psychotherapy and from day hospital psychotherapy to in-patient psychotherapy at threshold values of €12 120 and €132 866 per recovered patient-year, and €58 035 and €283 755 per QALY respectively.

Fig. 4 Cost-effectiveness acceptability frontiers (CEAF) showing the optimal modality for each value of the societal willingness-to-pay (WTP). (a) CEAF for recovered patient-year; (b) CEAF for quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

The switch points at which there is a change in the optimal option from out-patient psychotherapy to day hospital psychotherapy and from day hospital psychotherapy to in-patient psychotherapy were located at threshold values of €12 274 and €113 298 per recovered patient-year and €56 325 and €286 493 (not displayed in figure) per QALY.

Cost-effectiveness analysis from the payer perspective

The CEAF of cost per recovered patient-year and cost per QALY from the payer perspective show the same pattern of results as from the societal perspective. However, the switch points were located at different threshold values: €9895 and €155 797 per recovered patient-year, and €43 427 and €561 188 per QALY. When using a discount rate of 3% per year on outcomes, the switch points shifted marginally to threshold values of €9495 and €204 278 per recovered patient-year, and €44 580 and €500 151 per QALY.

Discussion

Main findings

Using decision-analytic modelling, we estimated the cost-effectiveness of three modalities of psychotherapy for cluster B personality disorders over a 5-year time horizon from both societal and payer perspectives. To our knowledge, this is the first assessment of the cost-effectiveness of treatment modalities for this population based on a formal decision-analytic modelling approach. As recommendations of current clinical guidelines in The Netherlands have been informed by limited economic evidence, we believe this study has the potential to inform clinical decision-making and healthcare resource allocations.

Our findings indicate that when the societal willingness-to-pay does not exceed €12 274 per recovered patient-year, out-patient psychotherapy provides the highest expected net benefit. If society is willing to pay more than €12 274 per recovered patient-year, day hospital psychotherapy is the optimal choice. Notably, in-patient psychotherapy would not be considered the most cost-effective treatment modality unless the threshold value reached €113 298. Defining an acceptable threshold for a recovered patient-year is challenging and without a common health metric the cost-effectiveness ratios cannot be readily compared with interventions for other illnesses; for example, the costs of a cluster B personality disorder recovered patient-year can only be compared with a depression recovered patient-year if they experience the same burden of disease. The use of QALYs as the health outcome allows for such a comparison across disease burdens, although there is no universally accepted threshold value. Our results in terms of cost per QALY can be interpreted according to recommendations by the Dutch council for Public Health and Health Care. 36 For acutely life-threatening illnesses (with a maximum burden of disease), an explicit maximum of €80 000 per QALY was recommended. For less life-threatening illnesses that only affect quality of life the council recommends a proportional lower acceptable threshold. Cluster B personality disorders are associated with severe impairment in quality of life. Reference Soeteman, Verheul and Busschbach6 The observed burden of 0.49 (i.e. mean EQ–5D index value of 0.51, range 0.50–0.52) indicates that treatments may cost up to €39 200 per QALY to be acceptable. Based on this threshold value, out-patient psychotherapy can be identified as the most cost-effective and thus the optimal option as it provides the greatest benefit below the threshold.

The adoption decision for out-patient psychotherapy is robust over the discount rates applied, which could be expected because we only model outcomes over a 5-year time horizon. Our results suggest that the two cost-effectiveness measures with different health outcomes yield similar trends in results, with out-patient psychotherapy being the optimal intervention at low levels of the societal willingness-to-pay, day hospital psychotherapy at higher levels and in-patient psychotherapy at the highest levels. The switch points in terms of cost per QALY occurs at higher threshold values, which can be explained by the fact that the distinction between modalities regarding health benefits was more pronounced in terms of recovery rate than in terms of QALYs. Consequently, the relatively low costs of out-patient psychotherapy carries more weight in the calculations of cost per QALY than of cost per recovered patient-year and leads to more favourable results for out-patient psychotherapy. Previous studies have suggested that the EQ–5D may be insensitive in capturing changes in the quality of life of patients with borderline personality disorders. Reference van Asselt, Dirksen, Arntz, Giesen-Bloo, van Dyck and Spinhoven37,Reference Brazier, Tumur, Holmes, Ferriter, Parry and Dent-Brown38 However, the health state utility weights calculated and used in the current analysis indicate that the EQ–5D, used to generate QALYs, can be considered sensitive to changes in patients with cluster B personality disorders. For example, participants in the recovered health state show health utility weights (i.e. a quality of life) approaching the utility weight observed in the normal (non-clinical) population (0.85); participants in the unchanged health state have a relatively stable utility weight compared with their value at enrolment (0.51); and those in the relapsed or deteriorated health state were assigned much lower health utilities compared with enrolment. Despite the sensitivity of the EQ–5D in distinguishing quality of life associated with particular health states, QALYs are nonetheless less adequate measures for discriminating levels of change between the different modalities of psychotherapy.

The cost-effectiveness results for the two effect measures indicate that out-patient psychotherapy and day hospital psychotherapy are more cost-effective for cluster B personality disorders than in-patient psychotherapy. Our findings are consistent with the scarce existing economic evidence identified by Brazier and colleagues in their systematic review evaluating the cost-effectiveness of psychological interventions for borderline personality disorders. Reference Brazier, Tumur, Holmes, Ferriter, Parry and Dent-Brown38 Based on best available evidence, their review suggests that both out-patient and day hospital treatment (i.e. dialectical behavioural therapy and mentalisation-based therapy) are likely to be a cost-effective treatment modality for borderline personality disorders.

Several clinical implications can be derived from our analyses. From a health economic perspective, out-patient psychotherapy and day hospital psychotherapy should be considered the options of first choice for patients with cluster B personality disorders, based on accepted willingness-to-pay thresholds. Interestingly, this conclusion is consistent with several efficacy and effectiveness studies. Reference Verheul and Herbrink12 Note, however, that this study attempts to inform recommendations from the public health (i.e. population) perspective and should be not used for individual decision-making. Although we used primary patient-level data from a clinical study, we used those data to inform population averages (and plausible ranges) for our parameters. As a result, we were limited in our ability to examine individual-level heterogeneity such that there will undoubtedly be some people for whom in-patient psychotherapy may be the best option. Also, we have to emphasise that cost-effectiveness is only one aspect of medical decision-making, so in daily clinical practice other important factors that were not considered in our model must be considered, such as individual preferences, past history, insufficient or even pathogenic social support systems. Our study has identified in-patient psychotherapy as an effective but expensive option; future research should test patient-treatment matching hypotheses in this respect.

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of this study was the collective use of the state of the art methodology and patient-level primary data to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of healthcare interventions. Decision-analytic modelling provides a framework for informed decision-making under conditions of uncertainty. Specifically, it allows for exploration of the impact of uncertainty across multiple parameters simultaneously and projection of results beyond the time horizon of the clinical trial. Furthermore, the availability of primary data from such a large patient trial provided a unique opportunity to inform the parameters of our model, as most modelling studies are based on secondary data. Data from future studies can be used to update the parameters of this existing probabilistic cost-effectiveness model.

Assumptions were made in this model-based analysis. To correspond to the model cycle length, the costs of healthcare utilisation post-discharge were multiplied by 6.5 to estimate the half-yearly costs. The extrapolation of these costs is based on the assumption that the recall period of 4 weeks of the TiC–P is representative for half a year. This assumption was tested in the same population in a previously published study, indicating that at a population level there was no significant difference between the costs as measured with a recall period of a year compared with a recall period of 4 weeks. Reference Soeteman, Hakkaart-van Roijen, Verheul and Busschbach5 We therefore believe that the costs calculated in the present study are a reasonable estimation of the actual costs generated over the model cycle length of 6 months.

Our analysis has several limitations. First, the model is developed using data from a treatment-seeking patient population, and in particular for those who seek specialised psychotherapy for personality problems. Therefore, the applicability of the results to non-treatment seekers, forensic care or individuals who present with a primary Axis I diagnosis is limited. Second, despite the fact that this population is known to use criminal justice resources these costs were not included in the analysis, which leads to an underestimation of the true societal costs. Third, this study compares only three modalities of psychotherapy, whereas the included treatments may also differ in terms of other characteristics such as theoretical orientation and therapeutic techniques. This limitation is somewhat mitigated by studies showing that theoretical orientation as a treatment parameter might only account for minor differences in effects – if any, Reference Svartberg, Stiles and Seltzer39,Reference Leichsenring, Rabung and Leibing40 and is not likely to be associated with costs. This is however not true for duration as a treatment parameter; future research should therefore address optimal dosing in terms of treatment duration. Finally, our analyses were based on a clinical trial with a non-randomised study design. That patients were not randomised over treatment conditions, however, is not a drawback but rather an advantage within the context of economic evaluations, because non-randomised studies are likely to be more representative and thus externally valid with respect to costs and effects. Reference Drummond, Sculpher, Torrance, O'Brien and Stoddart17,Reference Glick, Doshi, Sonnad and Polsky18 Moreover, randomisation between existing treatment options is no longer feasible because, once information about a therapy's clinical effectiveness is available, patients may not be willing to participate in experiments simply to evaluate its value for the cost. Exactly because of this reason, the same research group recently failed to conduct a randomised clinical trial comparing in-patient and out-patient psychotherapy for cluster C personality disorders. To overcome the problem of selection bias, we controlled for initial differences in patient characteristics with the propensity score method. Reference Bartak, Spreeuwenberg, Andrea, Busschbach, Croon and Verheul32

Implications

It can be concluded from our model-based analysis that out-patient psychotherapy and day hospital psychotherapy are the optimal treatments for patients with cluster B personality disorders in terms of cost per recovered patient-year and cost per QALY. The ultimate selection depends on which cost-effectiveness threshold is considered acceptable and what perspective is adopted. The decision whether or not to adopt a treatment strategy is inevitably made in a context of uncertainty surrounding the cost-effectiveness of these strategies, and therefore there is a possibility of making a wrong decision at a patient level. Future work should include a so-called value of information analysis that evaluates the extent to which additional evidence might reduce the probability and the consequences (costs) of a wrong decision and compares that improvement with the cost of information.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the contributions of the participating specialist centers of psychotherapy in The Netherlands: Center of Psychotherapy De Gelderse Roos, Lunteren; Medical Center Zaandam; Altrecht, Utrecht; Center of Psychotherapy Arkin, Amsterdam; GGZWNB, Bergen op Zoom; Center of Psychotherapy De Viersprong, Halsteren.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.