Background

Clozapine is the antipsychotic of choice for treatment-resistant schizophrenia given its unique efficacy,Reference Stroup, Gerhard, Crystal, Huang and Olfson1 but also has recognised benefits in reducing suicidalityReference Meltzer, Alphs, Green, Altamura, Anand and Bertoldi2 and aggression. Although the effectiveness of clozapine is widely acknowledged,Reference Stroup, Gerhard, Crystal, Huang and Olfson1,Reference Masuda, Misawa, Takase, Kane and Correll3 adherence with evidence-based guidelines recommending its use by clinicians remains particularly challenging.Reference Patel4 Thus, a substantial number of patients are eligible for clozapine months or even years before its definitive introduction.Reference Howes, Vergunst, Gee, McGuire, Kapur and Taylor5

Several studies have assessed the reasons for non-adherence with guidelines in the past few years, highlighting multiple factors related to patients, physicians, treatments and healthcare organisations.Reference Farooq, Choudry, Cohen, Naeem and Ayub6,Reference Gee, Vergunst, Howes and Taylor7 Concerns from patients and clinicians of serious adverse events are often mentioned as a barrier to clozapine initiation (such as neutropenia/agranulocytosis, myocarditis, seizures, paralytic ileus).Reference Rubio and Kane8–Reference Daod, Krivoy, Shoval, Zubedat, Lally and Vadas10 In addition, the need for repeated blood tests at the beginning of treatment is another obstacle to the introduction of clozapine.Reference Okhuijsen-Pfeifer, Cohen, Bogers, de Vos, Huijsman and Kahn11 Moreover, a significant proportion of psychiatrists (from 41% to 82%) mentioned prior non-adherence to antipsychotic treatment as a major barrier to the introduction of clozapine.Reference Gee, Vergunst, Howes and Taylor7,Reference Grover, Balachander, Chakarabarti and Avasthi9,Reference Daod, Krivoy, Shoval, Zubedat, Lally and Vadas10,Reference Swinton and Ahmed12,Reference Tungaraza and Farooq13 Indeed, several studies have shown that previous non-adherence to antipsychotic predisposes to future non-adherence.Reference Lacro, Dunn, Dolder, Leckband and Jeste14,Reference Ascher-Svanum, Zhu, Faries, Lacro and Dolder15

Weiss et al, however, reported in 2002 that clozapine improved adherence in non-adherent patients in the USA, but this study sample was relatively small (n = 162).Reference Weiss, Smith, Hull, Piper and Huppert16 Furthermore, most studies comparing discontinuation rates of clozapine with those of other antipsychotics found a significantly greater continuation of treatment with clozapine.Reference Vanasse, Blais, Courteau, Cohen, Roberge and Larouche17,Reference Weiser, Davis, Brown, Slade, Fang and Medoff18 Additionally, patients with psychiatric comorbidities and poor adherence to treatmentReference Leclerc, Demers, Bardell, Bilodeau, Williams and Tibbo19 are often difficult to study specifically in randomised controlled studies, and observational studies are particularly suitable to study this specific population.Reference Taipale and Tiihonen20

Aims

Given this widespread barrier limiting the use of clozapine in clinical practice and the lack of consensus in the literature, this study aims to determine if prior poor out-patient adherence to any antipsychotics before initiating clozapine predisposes to poor out-patient adherence to any antipsychotics and to clozapine after initiation of clozapine.

Method

Design and data sources

This retrospective cohort study extracted patient data from the Régie de l'assurance maladie du Québec (RAMQ), which administers universal health insurance for Quebec residents, including physician and hospital coverage. The RAMQ's universal health programme is complemented by a public drug insurance plan (PPDIP) that covers individuals without access to a private drug insurance plan, all last-resort financial assistance recipients and about 90% of individuals aged 65 and over. Previous analyses of a prevalent cohort indicated that 85% of patients with schizophrenia were on the PPDIP (data not shown).

RAMQ health databases include patient demographic data, a hospital discharge register (MED-ECHO), physician claims and the PPDIP. Demographic databases contain information about patient age, gender and eligibility for PPDIP. MED-ECHO contains primary and secondary diagnoses (ICD-9 before April 2006 and ICD-10 after that date),Reference Régie de21, Reference Régie de22 hospital admission dates and health procedures (for example surgical interventions). The physician claims database collects the date and diagnosis (ICD-9) of each service provided. The drug database includes information on drugs claimed from community pharmacies by individuals with coverage under the PPDIP. The database does not include in-patient medications. Individual patient records were linked to a unique encrypted identifier to provide demographic, medical and drug information.

Study cohort

Extracted from a larger cohort database on severe mental disorders (including schizophrenia, bipolar and other psychosis disorders), the study cohort included all patients with a prior diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9: 295; ICD-10: F20, F21, F23.2, F25), starting oral clozapine (with a clearance baseline period of 24 months without oral clozapine claim) between 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2016, and covered by the PPDIP 2 years before and 1 year after the first oral clozapine claim. The index date refers to the date of initiation of oral clozapine. In order to measure antipsychotic treatment out-patient adherence 1 year before and 1 year after the index date we excluded patients with a very long hospital length of stay (>9 months over 1 year before or >9 months over 1 year after) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Selection of the study cohort.

a. Two years before and 1 year clozapine initiation. b. With a clearance period of 24 months. c. Baseline period: 1-year period before clozapine initiation. PPDIP, public drug insurance plan.

Main variables: out-patient adherence measure before and after index date

Treatment out-patient adherence was measured by the medication possession ratio (MPR), which was calculated from data in the RAMQ drug database. MPR is widely used in the literature and is associated with clinical outcomes.Reference Valenstein, Blow, Copeland, McCarthy, Zeber and Gillon23 The MPR was obtained by dividing the number of antipsychotic medication supply days that the patient received from the out-patient pharmacy during the study period by the number of out-patient days (in order to exclude the number of hospital days). The threshold of 0.8 is generally used in the literature to indicate good adherence.Reference Valenstein, Blow, Copeland, McCarthy, Zeber and Gillon23

In the present study, three out-patient adherence measures were calculated and used to define the dependent and independent variables:

(a) independent variable (groups 1 to 5): adherence to any antipsychotics during the baseline year before index date (MPRprior) and categorised as good adherence MPRprior ≥ 0.8 (group 1) and four groups of poor adherence: MPRprior of 0.6 to <0.8 (group 2), MPRprior of 0.4 to <0.6 (group 3), MPRprior of 0.2 to <0.4 (group 4) and MPRprior < 0.2 (group 5);

(b) dependent variable 1 (binary): poor adherence to any antipsychotics taken as a whole category (including clozapine) (MPRantipsychotic < 0.8) during the year after index date;

(c) dependent variable 2 (binary): poor adherence to oral clozapine (MPRclozapine < 0.8) during the year after index date.

Covariables

The following covariables were assessed as they may potentially influence the adherence trajectory:

(a) gender assignment at birth (female/male);

(b) age at clozapine initiation;

(c) low socioeconomic status (defined as patients 65 years and older with pension income supplement or being a recipient of social welfare) (yes/no);

(d) status of schizophrenia diagnosis (incident/non-incident) (incident: date of the first diagnosis of schizophrenia occurring in the year before index date, non-incident: date of the first diagnosis of schizophrenia occurring more than 1 year before the index date);

(e) prescriber of the initial antipsychotic (psychiatrist/other clinicians);

(f) substance-related disorders (yes/no);

(g) history of personality disorder diagnosis (yes/no);

(h) use of: lithium (yes/no), divalproex (yes/no), antidepressants (yes/no), benzodiazepines (yes/no) or lamotrigine (yes/no) in the 12-month baseline period;

(i) hospital admission for schizophrenia or psychosis (yes/no), for another mental disorder (bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, etc.) (yes/no) or for a physical health reason (yes/no) during the 12-month baseline period;

(j) number of ambulatory visits (including emergency, out-patient and primary care clinics, etc.); and

(k) comorbidity index (0/≥1). Similar to Charlson's comorbidity index, the comorbidity index selected was proposed by Simard et alReference Simard, Sirois and Candas24 and was measured during the year before the index date. We excluded mental conditions including alcohol and drug misuse from the comorbidity index calculation.

Statistical analysis

A patient was considered exposed to the drug from the date(s) a prescription was claimed at a community pharmacy and for the time the drug was provided (index date). In cases where a patient received the first prescription at the hospital, the index date would still be the first out-patient prescription as no information on drug treatment during hospital admissions was available.

First, for each day of the 1-year baseline period before clozapine initiation, a patient was exposed to one of the eight categories of antipsychotics or was not exposed to any antipsychotics (the ninth possible category), except for in-patient stays (see Supplementary Figure 1; available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2022.1, for an example of an individual antipsychotic-use trajectory).

Second, for each day of the 1-year follow-up period after clozapine initiation, a patient was exposed to three possible categories (oral clozapine in monotherapy or polytherapy, other antipsychotic excluding clozapine or was not exposed to any antipsychotics) (see Supplementary Figure 2 for an example of an individual clozapine-use trajectory).

These antipsychotic utilisation trajectories (as patterns of antipsychotic use over time) before and after clozapine initiation were then presented stratified by the five baseline adherence-level groups (≥0.8, 0.6 to <0.8, 0.4 to <0.6, 0.2 to <0.4, <0.2) using the visual representations offered by the state sequence analysis method.Reference Vanasse, Courteau, Courteau, Benigeri, Chiu and Dufour25 As this approach is not inferential, to determine if previous out-patient adherence levels were statistically associated with poor out-patient adherence to any antipsychotics taken as a whole category (MPRantipsychotic < 0.8) and poor out-patient adherence to clozapine (MPRcloz < 0.8) after the index date, we also performed multiple logistic regressions including in the models all covariables mentioned above that were statistically associated with the dependent variables (backward stepwise selection, P < 0.1).

As supplementary analyses, we performed logistic regressions using 0.9 as a higher cut-point for good out-patient adherence, recognising that rapid readministration of clozapine after missing doses may have potential for harm in patients with schizophrenia. In addition, to see what happens after 1 year of follow-up, we performed the state sequence analysis and logistic regression analyses on a subcohort of patients with schizophrenia initiating oral clozapine from 2006 to 2014, allowing a follow-up of 3 years. We also measured the correlations between the MPR before index date (MPRprior) and both the MPR after index date (MPRantipsychotic and MPRclozapine). The analyses were carried out using SAS 9.4 and the TraMineR package in R for the visualisation of the trajectories.

Ethics and consent statement

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board Committee of the Université de Sherbrooke and by the Commission d'accès à l'information of Quebec. No informed consent is required for register-based studies using anonymised data.

Results

Study population, clinical and sociodemographic characteristics

The study included 3228 patients (Fig. 1), of whom 66.2% were men (Table 1). Patients had a mean age of 41.1 years. Five groups were formed according to the level of out-patient adherence to antipsychotic treatment – from the greatest (group 1) to the poorest (group 5) adherence – in the year before index date. Characteristics differed between groups. Younger patients were found in the groups with poorer adherence (MPRprior < 0.8) than group 1 (MPRprior ≥ 0.8). There was a higher proportion of ‘incident cases’ and a higher proportion of substance-related disorders in the poor adherent groups (groups 2 to 4). The use of antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and divalproex was more frequent in the greatest adherence group (group 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of the study population by baseline out-patient adherence level

MPR, medication possession ratio.

a. As a result of small numbers and ethical considerations, some information are not presented.

Hospital admission for schizophrenia and psychosis were more frequent in groups 2, 3 and 4. Group 5 had the lowest rate of hospital admissions for schizophrenia or psychosis, but the highest proportion of hospital admissions for a non-psychiatric reason. Group 5 had fewer ambulatory visits than the other groups in the year before the introduction of clozapine.

Antipsychotic-use trajectories 1 year before and after index date

The trajectories of clozapine use, other antipsychotics (non-clozapine) and non-use of antipsychotics were represented 1 year after the index date according to their prior level of out-patient treatment adherence (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 State distribution plot of antipsychotic treatment trajectories (left side) and hospital admission trajectories (right side) 1 year before and 1 year after oral clozapine initiation (index date)a stratified by baseline out-patient adherence level.

State distribution plot: as a summary for all patients' antipsychotic-use trajectories (left side), state distribution plots show the proportion of patients (y-axis) of antipsychotic use for each day of the 12-months period before and after the initiation of clozapine (index date). As opposed to the medication possession ratio (MPR) calculation, the antipsychotic trajectories representation do not take into account days spent in the hospital since pharmacy data were not available during hospital admission. This explains the antipsychotic use drop just before the index date (as shown by the hospital admission trajectories on the right side of the figure). a. With a 2-year clearance period without oral clozapine before the index date. CLOZ, clozapine; O, Oral; OLAN, olanzapine; RISP, risperidone; QUET, quetiapine; SGA, second-generation antipsychotics; FGA, first-generation antipsychotics; LAI, long-acting injectables; Poly, polypharmacy; mono, monotherapy; Hosp., hospital admission

These graphical representations include information about which out-patient treatment was used prior to the index date and whether it was continued or switched. Although group 1 had the highest number of patients (n = 2441) and the most favourable adherence rate in the year before index date, adherence was significantly improved in all groups regardless of the category of prior adherence to treatment. In addition, the majority of participants from all groups were admitted to hospital just before starting clozapine, mainly for urgent, semi-urgent or legal admission for mental disorder. This high hospital admission rate before introduction have contributed to the observed decline in the treatment-use trajectory shortly before the start of clozapine, as hospital-administered treatments were unavailable for the current analysis (Fig. 2). Interestingly, these findings were maintained up to 3 years after the initiation of clozapine (Supplementary Figure 3).

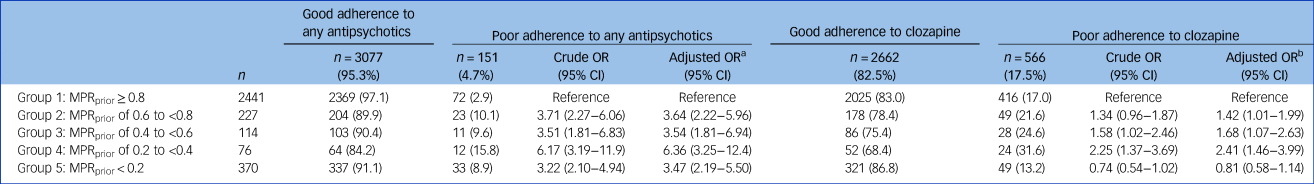

As the state sequence analysis is not an inferential approach, albeit providing powerful visual representations of antipsychotic-use trajectories, logistic regressions were performed as complementary analyses and are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Association between previous out-patient antipsychotic adherence level and poor out-patient adherence to any antipsychotics (dependent variable 1: MPRantipsychotic < 0.8) and poor out-patient adherence to clozapine (dependent variable 2: MPRclozapine < 0.8) after initiation of clozapine: results of the multiple logistic regression (reference: group 1)

MPR, medication possession ratio.

a. Adjusted for covariables in Table 1 statistically associated (P < 0.1) with the dependent variable 1: Hospital admission for schizophrenia/psychosis; number of ambulatory visits and substance-related disorders.

b. Adjusted for covariables in Table 1 statistically associated (P < 0.1) with the dependent variable 2: age; hospital admission for schizophrenia/psychosis; hospital admission for other mental disorders; hospital admission for non-mental disorders, substance-related disorders; number of ambulatory visits.

Out-patient adherence to any antipsychotics (including clozapine) after index date according to baseline out-patient antipsychotic adherence level

Table 2 shows the adjusted odds ratios (aORs) of poor adherence to any antipsychotic taken as a whole category after index date in groups with previous poor antipsychotic adherence (groups 2 to 5) compared with previous good antipsychotic adherence (group 1). The aORs demonstrated that poorer adherence level to antipsychotics before the index date was associated with an increased risk of poor adherence to any antipsychotic treatment after index date compared with group 1 (aORs ranging from 3.47 to 6.36). However, from 84.2% (group 4) to 97.0% (group 1) of patients had good adherence to any antipsychotic after introducing clozapine; hence, although the levels of adherence prior to and after introducing clozapine were significantly correlated, the MPRantipsychotic were nonetheless fairly high in all five groups.

Logistic regression using 0.9 as the cut-point for good adherence (Supplementary Table 1) produced essentially similar results. The Pearson correlation between MPRprior and MPRantipsychotic was 0.13 (P < 0.0001), indicating a small linear relationship between them.

Supplementary analyses on a subcohort (n = 2258) with 3 years of follow-up after clozapine initiation show that antipsychotic use, taken as a whole category, remains very high even after 3 years of follow-up, regardless of the previous adherence level: from 80.8% (group 4) to 92.4% (group 1) of patients had good adherence to any antipsychotic (Supplementary Table 2).

Out-patient adherence to oral clozapine (on monotherapy or polytherapy) after index date according to baseline out-patient antipsychotic adherence level

Table 2 shows the aORs for poor adherence to clozapine after index date in groups with previous poor antipsychotic adherence (groups 2 to 5) compared with previous good antipsychotic adherence (group 1). The results demonstrated that groups 2 to 4 (MPRprior from 0.2 to <0.8) had a greater risk of poor adherence to clozapine compared with group 1 (aORs between 1.42 and 2.41). Nevertheless, the overall proportion of patients adhering to clozapine over 1 year after its initiation varied from 68.4% (group 4) to 86.8% (group 5). The group showing the poorest antipsychotic adherence before starting clozapine (MPRprior < 0.2) was more likely to adhere to clozapine, but this was not statistically significant (confidence interval including 1).

Logistic regression using 0.9 as the cut-point for good adherence (Supplementary Table 1) produced essentially similar results. The Pearson correlation between MPRprior and MPRclozapine was, however, very low (r = 0.002, P = 0.9075), indicating no linear relationship between them.

Supplementary analyses show that clozapine use remains relatively high 3 years after its initiation: from 57.7% to 75.4% of patients had good adherence to clozapine (Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

Main findings

The results obtained with logistic regressions showed that previous poor antipsychotic adherence level compared with good adherence is an important risk factor of future antipsychotic poor adherence (aORs varying from 3.47 to 6.36) and clozapine poor adherence (aORs varying from 0.81 to 2.41). This supports the position of 41% to 82% of surveyed psychiatrists who mentioned prior non-adherence to antipsychotic treatment as a major barrier to the introduction of clozapine.Reference Gee, Vergunst, Howes and Taylor7,Reference Grover, Balachander, Chakarabarti and Avasthi9,Reference Daod, Krivoy, Shoval, Zubedat, Lally and Vadas10,Reference Swinton and Ahmed12,Reference Tungaraza and Farooq13

On the other hand, used in combination with logistic regressions, state sequence analysis allowed a complementary representation of complex patterns of antipsychotic use over time. As easily seen in Fig. 2, out-patient treatment adherence was significantly improved once clozapine was initiated, regardless of previous out-patient antipsychotic adherence level. Although these two elements could be perceived as contradictory, they only highlight the limits inherent to measures of association such as ORs and relative risks. Indeed, independently of their prior treatment adherence, very few patients had poor antipsychotic adherence (absolute risk varying from 2.9% to 15.8%) and poor clozapine adherence (absolute risk varying from 13.2% to 31.6%). In fact, more than 84.2% of patients with poor antipsychotic adherence (MPRprior < 0.8) before clozapine initiation were considered to have good adherence to antipsychotic treatment after clozapine initiation.

Altogether, these results sustain the initiation of clozapine in eligible patients regardless of their previous adherence profile, thereby allowing them to benefit from the many advantages of clozapine. Although this study was not aimed at comparing hospital admissions prior to and after the introduction of clozapine, Fig. 2 seems to suggest that the introduction of clozapine treatment was translated into a significant decrease in days spent in hospital.

Comparison with findings from other studies and interpretation of our findings

This manuscript enhances previous studies reporting that clozapine was less frequently discontinued than other antipsychotic treatmentsReference Masuda, Misawa, Takase, Kane and Correll3,Reference Vanasse, Blais, Courteau, Cohen, Roberge and Larouche17,Reference Weiser, Davis, Brown, Slade, Fang and Medoff18 and increased adherence.Reference Takeuchi, Borlido, Sanches, Teo, Harber and Agid26 As expected, the group with an MPRprior ≥ 0.8 had the most significant number of patients (n = 2441). Indeed, a bias toward clozapine introduction was found in patients who were more adherent to their treatment (MPRprior ≥ 0.8) compared with those who were less adherent (MPRprior < 0.8). In a similar manner, Weiser et al suggested that this type of bias could explain the lower discontinuation rates with clozapine as its introduction may have been reserved for patients with a greater propensity for repeated follow-up visits and monitoring.Reference Weiser, Davis, Brown, Slade, Fang and Medoff18 Despite the fact that clozapine was primarily prescribed for patients with favourable adherence (MPRprior ≥ 0.8) in the current study, patients with an MPRprior < 0.8 were still significantly adherent to both clozapine and any antipsychotic after initiating clozapine. Interestingly, a higher cut-point for good adherence (0.9) showed similar results.

The group with the poorest prior adherence level (group 5: MPRprior < 0.2) was especially noteworthy. Although group 5 had a lower proportion of hospital admissions for psychosis/schizophrenia than the other groups, this group seemed to have fewer contacts with the medical system. In particular, patients in this group had by far fewer ambulatory visits than the other groups. This may have influenced some covariables (such as substance-related disorders, history of personality disorder), as they theoretically consulted less, but our hypothesis remains that these patients were not less ill, but on the contrary more disaffiliated from the healthcare system.

Several hypotheses may explain the absolute increase in treatment adherence after initiating clozapine. As mentioned by Weiss et al, the proven efficacy of clozapine has the potential to decrease psychotic symptoms, improve cognitive symptoms and thus improve understanding of the need for treatment, and promote regular follow-up with a medical team to monitor treatment.Reference Weiss, Smith, Hull, Piper and Huppert16 Therefore, one could consider that clinicians may overestimate poor adherence to clozapine after its initiation, which must be put into perspective with our results. Still, adherence to treatment for people with chronic illnesses and particularly psychotic disorders remains a major issue in daily practice.Reference Lacro, Dunn, Dolder, Leckband and Jeste14

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to specifically investigate clozapine out-patient adherence according to different levels of prior out-patient adherence. In addition, this study examined the widely recognised barrier of non-prescribing of clozapine in patients with a history of poor adherence to antipsychotic treatment. Therefore, the combination of standard statistical methodology and an innovative approach resulted in a better understanding of the difference between relative and absolute risks of treatment adherence.

These results must be interpreted with caution, considering some limitations. Although all adherence measures are prone to their own limitations, the method used in this study (MPR) consists of an indirect measure of adherence.Reference Valenstein, Blow, Copeland, McCarthy, Zeber and Gillon23,Reference Valenstein, Copeland, Blow, McCarthy, Zeber and Gillon27 However, this measure is widely recognised as a reliable measure of adherence in pharmaco-epidemiological studies that use pharmacy data and is associated with outcomes such as psychiatric hospital admissions.Reference Ascher-Svanum, Zhu, Faries, Lacro and Dolder15,Reference Valenstein, Copeland, Blow, McCarthy, Zeber and Gillon27 In addition, the detailed profile of side-effects as well as reasons for discontinuation could not be specifically studied as our administrative database did not contain any information in this regard, a limitation shared by all such studies relying on large registries.

Our observational study could include some biases specific to the study of administrative databases (coding errors and missing data). However, the information from the RAMQ database is proven to be accurate.Reference Vanasse, Blais, Courteau, Cohen, Roberge and Larouche17 Still, our design allowed us to study a complex population, including patients eligible for clozapine, representative of patients found in clinics.

Another limitation is that information on the treatments used during the in-hospital period was not available in this database. This prevented us from obtaining an adherence measure encompassing the full period of observation. To limit the impact of the absence of treatment information during hospital admissions in the analyses, we had removed periods of hospital stay from the calculation of out-patient adherence (MPR); however, this was not possible for the antipsychotic treatment trajectory representation (state sequence analysis). Also, the length of follow-up before and after initiation of clozapine (1 year) remained limited in the treatment of schizophrenia. We thus performed a supplementary analysis on a subcohort with 3 years of follow-up, and the results remain impressively similar to the original analysis (Supplementary Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 2).

An additional limitation is that the use of several regression models may inflate the risk of a type 1 error. One way to minimise this error is the use of a multinomial logistic regression so that all the groups could be included in a single model. We thus performed a post hoc multinomial logistic analysis using the following outcome defined in three categories: (a) poor adherence to any antipsychotics; (b) poor adherence to clozapine but good adherence to any antipsychotics; and (c) good adherence to clozapine (Supplementary Table 3). The conclusions regarding the link between previous antipsychotic adherence level and future adherence to any antipsychotics were very similar to the original analysis. However, this post hoc analysis does not allow us to respond to if prior poor adherence to any antipsychotics before initiating clozapine predisposes to poor adherence to clozapine.

Finally, the study had a defined period of 24 months without clozapine, so patients may have received a previous trial of clozapine before that baseline washout period. Unfortunately, we were unable to quantify the real number of new versus old users as our database contained data only from 2002. Moreover, in order to accurately identify ‘true’ new versus old users, we would have to include only patients continuously receiving a PPDIP for a long period of time, which would have resulted in a significant selection bias (i.e. selecting patients with schizophrenia that were older and/or poorer). However, we tried to have an estimation of the proportion of new versus old users of clozapine using a subcohort of patients that were continuously covered over a 7-year period before and 1-year period after clozapine initiation (n = 2582). Among this subcohort, as low a number as 158 (6.1%) had received an out-patient prescription of clozapine during the 5-year period before the clearance period of 2 years.

Implications

Although we observed that poorer antipsychotic out-patient adherence prior to clozapine introduction increased the odds of later poor out-patient adherence, absolute rates of good adherence to any antipsychotics and clozapine remained high (>84.2% and >68.4%, respectively), regardless of prior antipsychotic adherence level. These results support the initiation of clozapine in eligible patients and may have an important potential to change a widespread barrier.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2022.1.

Data availability

The data are not publicly available because of privacy or ethical restrictions.

Author contributions

S.B., J.C., A.V., M.C., M.-A.R., E.S., A.L. and M.-J.F. contributed to the concept and design of the study, data gathering and interpretation. J.C. performed the analyses. S.B., A.V., M.-A.R., E.S., A.L., M.-J.F., M.-F.D., O.C. and L.B. contributed to the interpretation of the results in the context of clinical practice and mental healthcare. S.B. and J.C. drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Centre de recherche du CHUS (CRCHUS) and the Département de médecine de famille et de médecine d'urgence at the Université de Sherbrooke. This work was also partly supported by a grant from Janssen (division of Johnson & Johnson) and the Ministère de l’Économie et de l'Innovation (MEI), within the framework of Données de recherche en contexte réel – Partenariat Innovation-Québec-Janssen (PIQJ) administered by the Quebec Health Research Funds (FRQS).

Declaration of interest

E.S. received funding from Lundbeck Canada Inc. and Otsuka Canada Pharmaceutical Inc. He has served on the advisory boards and been a lecturer for Lundbeck Canada Inc, Otsuka Canada Pharmaceutical Inc, and Janssen. M.-A. R. reports grants from Mylan Canada, Janssen Canada, Mylan Canada and Otsuka-Lundbeck Alliance Canada during the conduct of the study. Outside the submitted work, he has also received personal fees from Boehringer Canada (research contracts), Lundbeck Canada (research contracts), Otsuka-Lundbeck Alliance (advisory honoraria; speaker honoraria), HLS Canada (advisory honoraria), Mylan Canada (advisory honoraria; speaker honoraria) and Janssen Canada (speaker honoraria). M.-F.D. reports grants from Mylan Canada, Janssen Canada and Otsuka-Lundbeck outside the submitted work. Outside the submitted work, she has also received personal fees from Otsuka-Lundbeck Alliance (advisory honoraria; speaker honoraria) and Janssen Canada (speaker honoraria). Except for the grant mentioned above, the authors declare no other competing interests.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.