1. Introduction

In the last decade, Wisconsin has become a symbol of the polarization and “norms-be-damned”Footnote 1 tactics that now characterize American policymaking. Prior to 2011, however, Wisconsin had a longstanding reputation for promoting progressivism and pluralist democracy, with high union membership,Footnote 2 a history of welfare and labor policy innovation, and idols like “Fighting Bob” La Follette, the Wisconsin governor and head of the Progressive Party in the early 1900s. In 2011, these traditions transformed into a “politics of resentment”Footnote 3 when the newly elected governor, Scott Walker, passed “Budget Repair,” a bill repealing a celebrated collective bargaining policy. How, then, did this contentious bill retrenching worker rights pass in a state once celebrated as “union country”?

Research on policymaking often emphasizes policies’ path dependence, showing how they create interests and stakeholders who act to preserve the status quo. When institutional change does occur, it is because strategic efforts from social movements mobilize policymakers toward change. However, this literature often does not account for the effect that improvised, subversive politics can have on the policymaking process. Expanding on this work, this study examines a case of significant institutional change, the passage of 2011 Wisconsin's retrenchment policy of Budget Repair. Based on an analysis of the policy's critical junctures, I argue that in the early stages, newly elected GOP politicians, under the influence of the Tea Party movement, used mobilization strategies to obfuscate costs, avoid blame, and secure votes from hesitant legislators.Footnote 4 However, these strategies ultimately devolved into a reactive struggle for power with entrenched Democratic legislators and previous policy beneficiaries. Integrating research on oppositional tactics,Footnote 5 then, I show how politicians in each party wrested control over the policymaking process by adopting subversive tactics that eroded governance norms.

2. Mobilization and Opposition in the Face of Change

Policies, norms, and procedures—as institutionalized structures that habituate action and take on “a rulelike status”Footnote 6—can have “lock-in effects”: in organizing power and resources, they establish institutional stakeholders and patterned action that is difficult to undo.Footnote 7 For example, the dramatic expansion of social welfare in the twentieth century created constituencies of policy beneficiaries willing to engage in activism to protect these programs.Footnote 8 These social policies also expanded government, creating bureaucrats with an interest in preserving and expanding these policies.Footnote 9 Institutional structures, thus, create incumbents who benefit from and reinforce the status quo.

When institutional change does occur, it often happens when insurgent social movements seize opportunities to target those in power, appealing to their identities and beliefs to mobilize them toward new ideologies and agendas.Footnote 10 For example, contemporary conservative movements created majorities in courts and local legislatures through legal and policy networks that subtly perpetuated conservative ideology.Footnote 11 Additionally, in the 2010 midterm campaign, GOP elites and conservative media partnered together with Tea Party activists to win majorities in the House and Senate.Footnote 12

In turn, policymakers often rely on these social movements for storytelling and framing that can package these agendas in meaningful ways. This often involves obfuscating, scapegoating, or exempting key constituencies to avoid blame when changing policies with lock-in effects.Footnote 13 Advocates for redistributive policy in favor of the wealthy, for example, were successful when they used “strategic policy crafting,” drawing on familiar policy frames and obfuscating social costs.Footnote 14 Generally, policymakers emphasize benefits and downplay risks to build or retain support.

However, contemporary work on institutional change does not yet fully articulate how strategies and political opportunity can change through ongoing interaction with opponents.Footnote 15 For example, work on conservative movements often focuses on premeditated strategies, showing how they create and mobilize Republican majorities to retrench social policy.Footnote 16 Similarly, analysts of abortion and same-sex marriage politics concentrate on how social movements on the left strategize preemptively against the “perceived threat” of conservatives rather than on any direct politicking.Footnote 17 Such analyses do not typically consider how these mobilization strategies can prompt improvised, direct responses from locked-in incumbents, who, through their action, complicate the path toward change.

Indeed, struggles for power can also invite more reactive oppositional tactics. In contrast to the mobilization strategies that build consensus through institutionally acceptable means (e.g., coalition-building, framing), these improvised tactics subvert the institutional mechanisms that give others control. The often-highlighted site for these politics is the workplace, where workers use everyday forms of deviance and resistance such as rule bending, theft, calling in sick, work slowdowns, and feigning productivity.Footnote 18 In contrast to more general theories of mobilization,Footnote 19 these organizational politics are particularly understood as “weapons of the weak,”Footnote 20 whereby those with less leverage subtly undermine the existing institutional structure to create change (e.g., new rules, more equity, more efficient production processes).Footnote 21

Extending work on institutional change, then, I argue that policymakers’ strategies for enacting change do not always anticipate the reactive responses that arise from lock-in effects, in which incumbents engage in their own efforts to protect the status quo. My argument does affirm that mobilization strategies,Footnote 22 which pursue institutionally accepted methods for generating consensus such as coalition-building, blame avoidance, and framing, are powerful tools for insurgents, in that they mobilize allies and constituents to action.Footnote 23 However, when, in spite of these strategies, insurgents still face ardent opposition from locked-in incumbents,Footnote 24 their efforts may devolve into reactive attempts to gain control. Engaged in a struggle for power, both incumbents or insurgents may turn to oppositional tactics, which, in eroding the institutional norms and rules that give opponents’ control,Footnote 25 help them to either preserve (incumbents) or advance (insurgents) their interests.

3. Analytic Approach

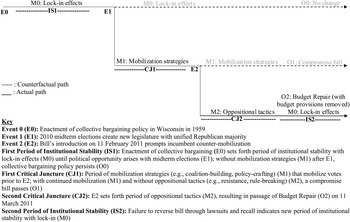

To analyze the passage of Budget Repair, I use the case method, which can show how institutions and actors change vis-à-vis ongoing interaction and identify causal mechanisms that elaborate on theories of change.Footnote 26 In particular, I use critical juncture analysis, examining the events and actions through which path-dependent institutional structures with lock-in effects become susceptible to change.Footnote 27 A critical juncture is a brief phase, following a period of institutional stability, during which an event creates opportunity. Critical juncture analysis, thus, involves constructing a narrative of the juncture, including the instigating event, the ensuing choices made, and the plausible alternative paths (i.e., counterfactuals). In analyzing policymaking, counterfactuals must be theoretically and historically consistent, representing a narrow range of policy options that were “available, considered, and narrowly defeated.”Footnote 28 Applying this approach to Budget Repair, I identified a period of institutional stability in which collective bargaining for public employees persisted (IS1 in Figure 1), followed by two junctures (CJ1 and CJ2 in Figure 1) in 2010 and 2011.

Figure 1. Events (E), Mechanisms (M), and Outcomes (O) during Periods of Institutional Stability (IS) and Two Critical Junctures (CJ), 1959–2011 Wisconsin

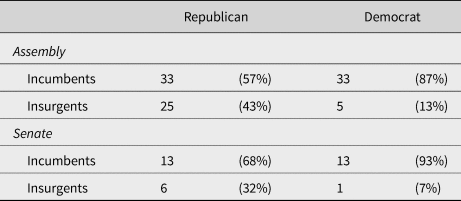

Using secondary sources on labor and collective bargaining history,Footnote 29 I traced how the passage of the collective bargaining policy (E0 in Figure 1) cultivated public-employee-union identities and broad bipartisan support, facilitating protection of these rights for more than fifty years (IS1 in Figure 1). The first critical juncture (CJ1 in Figure 1) followed the election of a new state legislature in the 2010 midterm elections (E1 in Figure 1). Analyzing the tenure and affiliations of legislators (presented in Tables 1 and 2) described in the 2009‒2010 and 2011‒2012 State of Wisconsin Blue Books, data on Wisconsin's legislative majorities from the Lucy Burns Institute, and work on contemporary conservative movements,Footnote 30 I identified how the 2010 midterm elections created a political opportunity for Republicans, giving them a unified government and the political will to make changes to the collective bargaining law.

Table 1. Composition of the Wisconsin State Legislature, 2011

Note: Legislators were coded as insurgents if they had been in that branch of the legislature for less than one year by January 2011.

Table 2. Business Ties in the 2011 Wisconsin State Legislature

Note: Business ties were recorded if legislators indicated that they were previously or currently a small business owner, business manager, or CEO.

However, my analysis of the previous period, the votes on Budget Repair, and the competing policy options circulating during the time of the bill indicated a theoretically and historically consistent counterfactual of the collective bargaining policy's continued path dependence (O0 in Figure 1). The original collective bargaining law, passed in 1959, had generated popularity for public-sector unions and collective bargaining in Wisconsin; as such, several incumbent Republicans had a stake in preserving the status quo and initially favored a budget policy that cut public program funding but not collective bargaining rights. Both the empirical reality and theories on lock-in and path dependenceFootnote 31 (M0 in Figure 1) suggested that the insurgent Republicans desiring change would need to mobilize votes or the bill would fail.

To understand how insurgent Republican legislators avoided this counterfactual outcome, I looked closely at newspaper articles, media interviews with legislators, government documents, and book-length accounts about Budget Repair.Footnote 32 I triangulated these accounts to identify key features of the bill—the “Budget” framing and the exemption of police and fire—that helped to mobilize the necessary votes. The findings were consistent with work on mobilization strategies,Footnote 33 indicating how insurgents can use framing and coalition building to move others toward change (M1 in Figure 1).

The second critical juncture (CJ2 in Figure 1) began after the bill's introduction (E2 in Figure 1), when a countermovement of public-sector employees and state Democrats complicated the efforts of the Republican insurgency. Again, I drew on primary and secondary accounts of Budget Repair's policymaking process as well as interviews with protest attendees,Footnote 34 finding that, even though insurgent Republicans secured the support of incumbent Republicans, these legislators did not anticipate the policymaking stalemate that would arise from the countermovement against Budget Repair. Consistent with the insurgency's previous strategies and theories on mobilization (M1 in Figure 1), they could have attempted strategic policy crafting once again to appeal to Democrats’ priorities and secure their cooperation in passing the bill.

However, Republicans ultimately rejected this option in favor of a more controversial choice. Frustrated by the opposition's stalling tactics, Republicans also defied procedure and bypassed the technical obstacle producing the stalemate. As described in the literature on oppositional tactics,Footnote 35 each side attempted to undermine their opponents through oppositional tactics that defied norms and rules (M2 in Figure 1), eventually resulting in Budget Repair's passage (O2 in Figure 1). While protests, recall elections for Republican senators and Governor Scott Walker, and several court battles continued over the next year, these efforts were unsuccessful in reversing the bill. Because of the failure of these actions, a new period of institutional stability and lock-in began (IS2 and M0 in Figure 1), indicating to me the end of the critical juncture analysis.Footnote 36

4. Institutional Stability (IS1): The Emergence of Public-Sector Collective Bargaining Rights (E0) and Subsequent Lock-in Effects (M0)

My analysis of historical accounts of the initial 1959 collective bargaining policy, public opinion, and legislative majorities in Wisconsin following the initial policy's passage, indicate that, in addition to securing bargaining rights for public workers, the policy created stakeholders with an interest in protecting those rights. Collective bargaining rights for public-sector workers emerged in the mid-twentieth century to address disparities in wages and benefits between these workers and private-sector employees. The National Labor Relations (Wagner) Act of 1935 enabled private employees to negotiate contract terms, wages, and working conditions via union organization. However, public-employee-union rights were not federally mandated and were stalled in state policymaking because of lack of public support, the emerging “right-to-work” movement of the 1940s, and fear of permitting public workers, particularly police, with the right to strike. Despite these setbacks, however, the labor movement continued to grow, and organizations such as the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME)—which originated in Wisconsin—emerged using informal negotiation tactics and lobbying to advocate for public-employee interests.Footnote 37

In the 1950s, the Wisconsin chapter of AFSCME, the Wisconsin Council of County and Municipal Employees (WCCME) began lobbying the state legislature to implement public-employee union rights, with extensive efforts to pass bills in 1951, 1955, and 1957. Republican majorities in the legislature killed such attempts each time, often citing concerns about police strikes and walkouts.Footnote 38 In 1958, however, Democrats made gains in both the Assembly and governorship for the first time in decades and growing public support for unions provided a new opportunity. WCCME crafted a new bill, which excluded public safety officials like police and included a commission that would oversee any conflicts or impasses. In 1959, with a few revised provisions, the legislature passed the bill and Wisconsin became the first state to recognize public-sector unions and their rights.

Over the years, policymakers amended the original 1959 law. In 1961, the Wisconsin legislature elaborated the role of the commission in arbitration, authorized legally binding collective bargaining agreements, and prohibited strikes. In 1965, it extended rights from local government employees to those in state government.Footnote 39 The legislation, however, still excluded police and firefighters, who continued to strike illegally until legislators passed an amendment to include these workers in 1971.Footnote 40

The 1959 policy, and its subsequent amendments, had local feedback effects in Wisconsin. By endowing public employees with the right to negotiate their contracts and conditions, it expanded union membership and political power. In an indication of public employees’ increased organizational capacity, the number of bargaining units grew to nearly 2,000 in the period following the 1959 policy and before the passage of Budget Repair.Footnote 41 The policy also had cognitive consequences, contributing to the creation and legitimation of public-employee union identities and mass acceptance of public-sector unions in Wisconsin. According to polls, between 53 and 71 percent of the Wisconsin general public supported public-employee unions and collective bargaining by 2011.Footnote 42 As the first state to pass public-sector collective bargaining and a holdout against “right-to-work” policies, Wisconsin emerged as a bastion of the progressive movement and union organizing.

Indeed, the public popularity of unions and collective bargaining in Wisconsin corresponded with bipartisan preservation of the law. Prior to the midterm elections of 2010, repealing collective bargaining was not a prioritized agenda for either Democrats or Republicans in Wisconsin. From 1992 until 2010, Republicans had majority power in two of the three legislating state bodies (Senate, Assembly, or governorship) for twelve of the observed eighteen years.Footnote 43 For two of these years, 1995 and 1998, Republicans had a fully unified government,Footnote 44 and yet they did not enact any policies that challenged the collective bargaining law. Rather, it appears that the more entrenched interest for both Republicans and Democrats in Wisconsin was to avoid such legislation.

Thus, my analysis of historical accounts of the worker organizing, public opinion on public-sector unions and their rights, and legislative majorities in Wisconsin suggests that the passage of the 1959 policy (E0 in Figure 1) not only provided concrete benefits for public employees, but also generated powerful lock-in effects (M0 in Figure 1) that contributed to its long-term persistence (IS1 in Figure 1). In the periods preceding and following the passage of the 1959 public-sector bargaining law, public employees became a critical part of Wisconsin's labor movement; the institutionalization of their rights through the law also institutionalized their organizational identities as public employees. Their presence, and the continued popularity of unions and collective bargaining among the public, made it politically risky for legislators of any party to make changes to the law, facilitating its persistence for more than fifty years. Such lock-in effects eventually presented challenges throughout the two critical junctures of Budget Repair's passage, creating both hesitance among incumbent Republicans to support Budget Repair (during CJ1 in Figure 1) and oppositional resistance from Democrats and their entrenched public-employee constituents (during CJ2 in Figure 1).

5. First Critical Juncture (CJ1): The 2010 Midterm Elections (E1), the Counterfactual Path of Lock-in (M0), and the Chosen Path of Mobilization Strategies (M1)

Analyses of primary and secondary accounts of conservative movements, the 2010 midterm campaign, and the elected 2011 Wisconsin state legislature suggest that the emergent Tea Party movement in the 2010 midterm elections created a new Republican majority (E1 in Figure 1) and, as a result, a critical juncture (CJ1 in Figure 1) during which GOP insurgents had an opportunity to make changes to Wisconsin's public-sector bargaining laws. However, my analyses of the previous period (IS1), competing policy options, the Budget Repair vote tally, and reports of hesitant incumbent Republicans also indicate a counterfactual path in which the lock-in effects of the 1959 policy could have influenced these key legislators to reject the bill (E1 to O0 in Figure 1). To convince these Republican colleagues and secure their votes, the new Republican insurgency used strategic policy crafting, giving these incumbent legislators a means to avoid blame and maintain the support of powerful constituents. Mobilization strategies (M1 in Figure 1) thus facilitated the policymaking process until the next critical juncture (CJ2 in Figure 1).

5.1 The 2010 Midterm Elections (E1)

In 2010, Republican politicians were using symbols of business efficiency, austerity, and fairness to condemn President Obama's first two years in office, the state of the Great Recession, and Democrats’ management of the economy and federal budget deficit. These discussions were a reflection of two major factions in conservative politics at the time: (1) business elites, who were drawing on logics of the free market and efficiency to advocate for a pro-business agendaFootnote 45 and (2) the Tea Party, which was channeling mounting white anxiety and rural resentment to advocate for a smaller government that favored “hard-working” Americans, as opposed to “freeloaders.”Footnote 46

During the midterm campaign, these two factions partnered together to put forth a vision of fiscal conservatism.Footnote 47 Business, conservative media, and Tea Party activists argued that President Obama and Democrats, through the policies like the Affordable Care Act and American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, had run rampant with spending projects.Footnote 48 The influential Americans for Prosperity, largely supported by business elites the Koch brothers, served as a primary vehicle for organizing Tea Party rallies and election campaigns.Footnote 49 In 2010, this campaign succeeded, with Tea Party politicians replacing many Democrats’ and more centrist Republicans’ seats in Congress.

The conservative movement permeating national politics also had local effects in Wisconsin. The state Senate and Assembly transitioned from a Democratic majority to a Republican majority in 2010, with a considerable number of novice legislators and business elites contributing to this majority. Upon the inauguration in January 2011, the number of novice Republicans was five times larger than the number of novice Democrats in the state Assembly and six times larger in the state Senate, indicating a strong Tea Party influence in the Republican legislature (see Table 1). Furthermore, business was the largest single professional background represented among Republican legislators and exceeded the business representation among Democratic legislators by double (see Table 2).

As a gubernatorial candidate who would eventually have aspirations for higher office, Scott Walker won the governor's race by capitalizing on the Tea Party discourse and the growing resentment of liberal elites, urban centers, and public institutions within Wisconsin's primarily white and rural communities.Footnote 50 Positioning himself as a reformer willing to bring bold changes to government, he also attracted the support of business elites like the Koch brothers, who saw him as a vehicle for their anti-union agenda.Footnote 51 Furthermore, the Bradley Foundation, a think-tank funder promoting anti-union ideology in Wisconsin, facilitated Scott Walker's political grooming, with the president Michael Grebe chairing his campaign.Footnote 52

The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a conservative organization that drafts pro-business policies for state legislators, was another clear influence on Walker's policy agenda. The incoming governor was a longtime ALEC member and, in his first year, signed nineteen ALEC bills into law. While Budget Repair was not modeled on one particular ALEC policy, it drew heavily from the organization's anti-union policy ideas, including preventing unions from mandatorily enrolling members and collecting dues.Footnote 53 To be sure, ALEC's retrenchment agenda was reflected in a substantial amount of legislation introduced nationally in 2011 and 2012 curbing union rights, including 820 bills in nineteen states.Footnote 54 Armed with these policy models and noticing the “stable of newly elected conservatives in both chambers who were eager to shake things up,”Footnote 55 the insurgent governor saw an opportunity to enact the reform that would be his signature legislation.

5.2 Counterfactual: Lock-In (M0) and No change (O0)

The political opportunity provided by the midterm elections (E1 in Figure 1) was a necessary but not sufficient condition for changing the public-sector bargaining policy, given that the policy's lock-in effects (M0 in Figure 1) could have generated a counterfactual path that preserved the law (O0 in Figure 1). Because of unions’ popularityFootnote 56 and polling that suggested that “economy and jobs” and “budget, deficit, and taxes” were top concerns for Wisconsin voters,Footnote 57 a polarizing bill that did not have a clear connection to these issues was politically risky for incumbent legislators, especially for those from moderate and swing voting districts. According to several accounts, many incumbent Republicans, particularly those in the Senate and with ties to organized labor, expressed little desire to participate in legislation explicitly aimed at dismantling public-sector unions.Footnote 58 Senator Luther Olsen (R) emphasized this concern publicly right before the bill's introduction, expressing that he was ready to take on cuts to pensions and healthcare but not to strip collective bargaining away from “a lot of good working people.”Footnote 59 Senator Kapanke (R) expressed a similar sentiment, saying that the vote on Budget Repair was “one of the toughest votes.”Footnote 60

Such evidence suggests that the handful of votes that ensured an eighteen-vote majority and the bill's passing in the Senate on March 11, 2011, were not inevitable achievements but were hard-won. The Wisconsin State Senate consists of thirty-three seats, which in 2011 included nineteen Republicans and fourteen Democrats. The final vote in the Senate for Budget Repair was 18–0,Footnote 61 with one incumbent Republican, Senator Dale Shultz, voting no. Up until the vote, however, at least two incumbent Republicans aside from Shultz—perhaps even “‘five or six’ from moderate districts” by some reportsFootnote 62—were publicly wavering on the bill. If even two of these senators acted on their hesitance or any entrenched interests in their voting districts, Budget Repair would have died in the Senate.

Indeed, other policy models that focused strictly on budget issues may have been more appealing to these hesitant senators. From a public policy perspective, the specific provisions in the Budget Repair bill, on their own, did not immediately connect with these legislators’ primary priority: the economy. While other states with public-sector collective bargaining laws had slightly higher deficits, the budgetary problems of states in 2010 and 2011 were largely attributed to the recession.Footnote 63 More fitting policy measures for resolving the budget crisis at that time, then, would have been those proposed by both Tea Party and moderate Republicans during the midterm election campaigns, such as cutting programs that drew directly from state budgets. Many state legislatures in 2011 were making cuts to welfare programs, including reducing Medicaid coverage and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).Footnote 64 Other, more fitting, policy models that focused on austerity and program cuts were thus available as an option for Wisconsin legislators looking to address the budget crisis.

Public-employee unions in Wisconsin—having failed to pass a contract with the previous legislature in December—were anticipating these austerity measures and were ready to negotiate and mobilize around any proposed legislation. They, and incumbents like Senator Luther Olsen (R)—who was ready to support such cuts—were shocked when the revealed bill went much further.Footnote 65 By Walker's own account, each time he shared his proposal to restrict collective bargaining with Republican legislators in the months leading up to public introduction, he was met with hesitance or responses that he had “lost his mind,”Footnote 66 indicating that rejection of the bill from incumbent senators was possible. To avoid a counterfactual outcome in which public-sector bargaining persisted (counterfactual path from E1 to O0 in Figure 1), the bill's advocates had to make a case as to why restricting collective bargaining should be a policy priority in the context of more pressing budgetary issues.

5.3 Mobilization Strategies (M1)

To make this case and mobilize hesitant incumbent senators, the bill's proponents used mobilization strategies (M1 in Figure 1). First, in naming the bill “Budget Repair” and framing all changes to public employment as solutions to the budget crisis, they obfuscated the loss of public-employee unions’ bargaining rights. In the publicly announced version of the bill, Walker connected balancing the budget to collective bargaining, stating, “this budget repair bill will meet the immediate needs of our state and give government the tools to deal with this and future budget crises … through changing some provisions of the state's collective bargaining laws.”Footnote 67 The press release summarizing the bill listed fiscal measures first—such as “Pension contributions” and “Health insurance cost containment strategies”—with the more controversial collective bargaining measure toward the bottom. Walker and his colleagues further obfuscated by including more familiar welfare-oriented provisions that gave the governor more power to reorganize funding for Medicaid and TANF programs, which had more clear connections to the state budget.

Additionally, the bill framing connected with the Tea Party argument of “fairness.” Walker contended that the bill would end union cronyism and ask employees to make healthcare and pension contributions equivalent to those of private-sector employees.Footnote 68 This argument cut to the Tea Party's “freeloader” concern, a point that a sympathizer echoed during our interview. As a teacher at a charter school (and thus, not unionized), she thought unionized public teachers had an unfair advantage, stating, “I don't deem it [collective bargaining] a right … it's a luxury … I just wanted the playing field leveled.”Footnote 69

Walker and his colleagues also framed the bill as economically efficient to appeal to Republican legislators. They suggested that the bill would lower the state's interest rate, save nearly $200 million and “lay the foundation for a long-term sustainable budget … without raising taxes.”Footnote 70 Walker restated this logic in his account, reasoning that even with a Republican majority, Budget Repair would not have passed were it not for “the magnitude of the deficit” and the ways the policy would “balance the budget.”Footnote 71 In a nod to the business-minded approach of both the bill and the GOP, he held up a “Wisconsin is open for business” bumper sticker when signing the bill into law on March 11, 2011.

The final key policy design was the exemption of police and firefighters, a constituency who historically concerned Wisconsin lawmakers. Police and firefighter unions in Wisconsin, initially barred from the 1959 collective bargaining policy, had a history of striking and walkouts, even in spite of laws prohibiting such action.Footnote 72 Madison firefighters also had a history of striking and were encouraged by the union president to do so following the introduction of Budget Repair, despite their exemption.Footnote 73 This history suggests that if police and firefighters had been included in the bill, a walkout by the whole of law enforcement would have been possible.

In addition to threat of walkouts, including public safety officials in the bill would have been politically risky. Several of the 300 police and firefighter unions in Wisconsin had endorsed Walker for governor.Footnote 74 Additionally, during the time after September 11, 2001 (but prior to movements for Black lives and police reform), the public was largely supportive of law enforcement communities.Footnote 75 A bill including police and firefighters, then, would have risked activating this powerful constituency. However, Governor Walker acknowledged that exempting this particular public sector was not initially an intended measure but was included after a few top Republican colleagues echoed the early concerns around the1959 policy: the risk that police and correctional officers would walk off the job.Footnote 76

Thus, while the midterm elections (E1 in Figure 1) gave Scott Walker and his allies a majority in the legislature, they needed first to secure the votes of incumbent Republicans. Reducing collective bargaining rights was not an inherent Republican motivation in Wisconsin prior to 2011, where the 1959 policy had created powerful constituencies of public union supporters and lock-in effects (M0 in Figure 1). Other policy options were available to address the budget crisis, so Walker had to convince these incumbents that cutting collective bargaining for public workers was the most viable path, particularly if law enforcement threatened a walkout. Without incumbent Republicans’ support, Budget Repair would have failed in the state Senate and the collective bargaining policy would have persisted (counterfactual path from E1 to O0 in Figure 1). Through mobilization strategies that framed the bill as “Budget Repair” and exempted police and firefighters from the bill (M1 in Figure 1), Walker and his allies secured the necessary votes.

6. CJ2: Incumbent Countermovement Following Budget Repair's Introduction (E2), a Counterfactual Path of Continued Mobilization Strategies (M1), and the Chosen Path of Oppositional Tactics (M2)

My analysis of primary and secondary sources on the protests and bill proceedings indicates the countermovement of Senate Democrats and public employees following the bill's introduction (E2 in Figure 1) complicated the bill's path. News reports and released emails of legislator negotiations suggest that following this event, Republicans considered pursuing more mobilization strategies (M1 in Figure 1) that would have created a compromise bill to lure Democrats back for a vote (counterfactual path to O1 in Figure 1). Instead, Republicans, frustrated with Democrats’ continued opposition, also defied political norms to rush the bill's passage. These events indicate that, engaged in a struggle for power, politicians in each party used oppositional tactics (M2 in Figure 1) to gain leverage over the policymaking process during the second critical juncture (CJ2 in Figure 1), ultimately resulting in the bill's passage (O2 in Figure 1).

6.1 The Introduction of Budget Repair (E2) and Incumbent Counter-Mobilization

Like the reaction of incumbent Republicans, Senate Minority Leader Mark Miller (D) and Assembly Minority Leader Peter Barca (D) were alarmed by the bill's radical measures, telling Governor Walker in a meeting just moments before the bill's introduction on February 11, 2011, that he was “blowing up the state.”Footnote 77 Public workers were also surprised; the Teaching Assistants Association at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-Madison) had already coordinated a Valentine's Day demonstration to protest what they expected would be cuts to the UW system. However, when the announcement revealed that gutting collective bargaining was part of the bill, they shifted their efforts to a more disruptive strategy.Footnote 78

Following the initial Valentine's Day demonstration, thousands showed up at the state capitol daily, disrupting the bill's legislative proceedings. On February 15, 2011, masses of protesters arrived to participate in Assembly hearings over the bill, “a citizen filibuster” that lasted until 3 a.m.Footnote 79 This event also inspired encampments in the capitol rotunda as protesters targeted lawmakers and waited for their turn to speak. On February 22, 2011, assembly members began debating the bill, a session that became the longest in state history.Footnote 80

In addition to these tactics, a critical form of disruption was the action by the fourteen Democratic senators who fled the state in response to the bill. Wisconsin state law requires a quorum of at least twenty senators for votes involving budget provisions. Just shy of this number with nineteen senators, the Republican Senate needed at least one Democratic senator present to pass the bill. However, on February 17, 2011, when the bill was up for vote, Senate Democrats fled to Illinois to prevent the quorum. Citing the injustices of the bill and its assault on Wisconsin workers and history, these senators used their absence to pursue a compromise bill that would concede some fiscal provisions but preserve collective bargaining rights.Footnote 81

6.2 Counterfactual: Mobilization Strategies (M1) and Compromise (O1)

By fleeing the state, Senate Democrats did create a window of opportunity, prompting Republicans to consider mobilization strategies (M1 in Figure 1) that would produce a compromise bill with Democrats (counterfactual path from E2 to O1 in Figure 1). Throughout the protests, Governor Walker and Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald also considered removing the budget items that necessitated the quorum, to facilitate the bill's passage.Footnote 82 Up until March 9, 2011, however, many incumbent legislators were hesitant to support such changes; as Walker stated, they “didn't want to send the message that the bill was about breaking the unions instead of balancing the budget,”Footnote 83 which, indeed, would have challenged the framing of “Budget Repair.” Instead, these Republicans asked that Walker “tone down” his proposal.Footnote 84

Throughout this time, then, Governor Walker and his allies pursued talks with senators Cullen (D) and Jauch (D) about a compromise, while also attempting more aggressive tactics to lure them back (e.g., publicly blaming them for shirking their duties, issuing fines, and filing recall petitions).Footnote 85 On the one hand, the Democrats were holding out for a compromise that would include the preservation of collective bargaining for public employees, a stance that had the support of both public workers and the public (in polls).Footnote 86 On the other hand, the Walker administration remained adamant about restricting collective bargaining in some capacity but was open to making changes that would allow public-sector unions to bargain over mandatory overtime, hazardous duty pay, and workplace safety and also open to dropping the restriction that tied bargaining over wages to inflation.Footnote 87

If they had successfully negotiated with Democrats, a less restrictive bill could have emerged. While Walker and his allies were never likely to completely retreat from their goal of weakening unions, Democrats could have negotiated to preserve some key pieces of the collective bargaining law, particularly regarding pay and workplace conditions. Continued mobilization strategies on both sides (M1 in Figure 1), then, would have produced a counterfactual path in which Budget Repair would have been replaced with a newly negotiated bill that included small gains for each party (E2 to O1 in Figure 1).

6.3 Oppositional Tactics (M2)

However, each party's continued use of oppositional tactics (M2 in Figure 1) eventually foreclosed this counterfactual path. In public statements during the week of March 7, 2011, Senator Mark Miller (D) criticized Republicans’ unwillingness to compromise, while Governor Walker claimed otherwise, revealing emails in which his office was negotiating with other Democrats.Footnote 88 Frustrated and blaming Miller for a botched compromise, Governor Walker met with the Republican Senate on March 9, 2011, to discuss removing budget items from the bill. During the meeting, which he described as “testy” and fraught with uncertainty,Footnote 89 he delineated a choice between splitting up the bill or raising taxes and gutting schools. Following this meeting, the Republican legislators decided that removing some of the budget provisions was the only way to overcome the stalemate.Footnote 90

The same day, Republican leaders in the Assembly rushed the bill through conference committee, giving less than two hours’ public notice before their brief meeting. While arguably violating the state's open meetings laws, GOP leadership worried that with more delays and public deliberation, the votes for the bill would not hold.Footnote 91 Shortly after, the Senate voted; all but one Republican senator supported the bill, though none commented after their vote that day.Footnote 92 The next day, the Assembly held a vote, passing the bill 53–42, with one assemblymember abstaining. On March 11, 2011, Walker signed the bill into law, marking the bill's deliberation period (24 days) as among the shortest in Wisconsin history.Footnote 93

Thus, after the bill's introduction (E2), the countermovement of public employees and Senate Democrats complicated Republicans’ efforts. Fleeing the state and creating a stalemate were oppositional tactics (M2 in Figure 1) that allowed Democrats’ some leverage to negotiate with Republicans. If Republicans had continued with mobilization strategies (M1 in Figure 1) to lure these Democrats back, they could have created a compromise bill in which public employees retained some or all of their collective bargaining rights but conceded on some fiscal matters (counterfactual path from E2 to O1 in Figure 1). However, eventually frustrated with Democrats’ continued resistance, Republicans also resorted to oppositional tactics (M2 in Figure 1). Like their counterparts, Republican legislators defied precedent and procedure, bypassing the quorum requirement, holding closed-door meetings, and rushing any deliberation to ensure Budget Repair's passage.

7. Discussion

As the epicenter of a national labor movement for public-sector bargaining, Wisconsin passed the first policy in 1959 (E0 in Figure 1) and, in doing so, produced effects beyond allocating those rights. The passage of the first public-sector collective bargaining policy both facilitated the expansion of public-employee labor unions and affirmed public employees’ identities as union members. As the policy became institutionalized over time, it also became a celebrated Wisconsin tradition. The policy, thus, enjoyed an over 50-year tenure (IS1 in Figure 1), in which legislators, public employees, and public opinion, through lock-in effects (M0 in Figure 1), supported and preserved the status quo.

In 2011, an opportunity to retrench the policy emerged when a national Tea Party insurgency delivered a unified Republican government to the Wisconsin State Legislature (E1 in Figure 1). However, a cadre of incumbent Republicans, though generally sympathetic to the Tea Party insurgency's goals, were hesitant to overturn such a popular policy; without their votes, the collective bargaining policy would have remained unchanged (O0 in Figure 1). To secure their votes, the insurgency buried the threat to collective bargaining rights in other familiar policy provisions that more directly affected state budgets. To appeal to GOP sensibilities, they also positioned Budget Repair as a cost-saving measure that would resolve the deficit and lead to more economic prosperity and fairness. Finally, Republican lawmakers exempted police and firefighters from the bill, preempting any major opposition from these key Republican constituencies. These mobilization strategies (M1 in Figure 1) built a majority that could change the collective bargaining law (CJ1 in Figure 1).

However, the insurgency did not anticipate the massive countermovement that emerged. Following public-employee protests, Senate Democrats decided to engage in their own opposition (M2 in Figure 1), fleeing the state to stall the bill's proceedings. Republicans attempted to build consensus for a short while, negotiating a compromise bill that would have preserved some bargaining rights for public workers (O1 in Figure 1). However, eventually, frustrated by Democrat obstinance, they opted for a more controversial course, removing fiscal items from Budget Repair to bypass the quorum requirement. They also veiled these controversial decisions with closed-door meetings, rushed votes, and limited engagement with the public following the vote. With these tactics (M2 in Figure 1), Republicans passed Budget Repair (O2 in Figure 1).

Theories on institutional persistence suggest that policies have lock-in effects, creating institutional relationships, stakeholders, and movements that work to ensure policies’ path dependence.Footnote 94 Such lock-ins can be overcome when insurgents seize political opportunities and mobilize key allies toward change.Footnote 95 In the context of policymaking, these mobilization strategies often involve “strategic policy crafting,”Footnote 96 whereby policymakers emphasize benefits and downplay risks to appeal to allies and avoid blame.Footnote 97

The analysis presented above provides some support for these theories. The lock-in effects (M0 in Figure 1) of the 1959 policy (E0 in Figure 1) created incumbents who ensured the policy's path-dependent, 50-year tenure (IS1 in Figure 1). Recognizing the opportunity from the 2010 midterm elections (E1 in Figure 1), the insurgency drew on familiar policy frames and obfuscated social costs to provide ample political cover for hesitant Republicans. Such mobilization strategies (M1 in Figure 1) created the coalition needed to pass Budget Repair (CJ1).

However, typically, this literature overlooks how such strategies can prompt subversive responses from locked-in incumbents and stakeholders and how this struggle for power can complicate insurgents’ efforts.Footnote 98 Indeed, theories on mobilization could not fully illuminate the reactive sequences in this case, when, following the bill's introduction (E2 in Figure 1), Democrats fled the state to avoid a quorum and Republicans, in turn, worked to overcome this stalemate (CJ2 in Figure 1). Building on this work, then, I incorporate theories of organizational devianceFootnote 99 to argue that when mobilization strategies fail to generate a sufficiently powerful coalition, insurgents may turn to oppositional tactics, subverting the norms and rules that give opponents control. Democrats’ shirking of Senate duties and Republicans’ tactics to evade deliberation and public involvement were forms of oppositional tactics (M2 in Figure 1) that flouted policymaking norms to recover political leverage.

8. Conclusion

The institutional change that accompanied Budget Repair in 2011 set off a wave of local anti-union legislation, with eighteen states considering retrenchment policies that year. It was also part of a new shift in contemporary politics, with Wisconsin becoming a symbol of the increasing divide between urban and rural, left and right, and various racial and ethnic groups. My analysis of this case helps to advance understanding of this contemporary period of political hostility, showing how political parties and movements subvert their opponents’ efforts and power. In the case of Budget Repair, policymakers, rather than using strategies to build consensus, opted for subversive tactics that eroded governing norms, marking a new period of retrenchment policy and polarization in American politics.

This study, then, lays the groundwork for furthering work on oppositional tactics and their implications for democratic governance. For example, a unique feature of the Trump administration was its repeated defiance of political norms, and the crises that have emerged as a result.Footnote 100 However, Trump was not the first to engage in this form of politics; he was preceded by President Obama's and President Bush's unprecedented expansions of executive powerFootnote 101 and Senate Republicans’ defiance of norms in 2016, when they refused to deliberate Merrick Garland's nomination to the Supreme Court.Footnote 102

At the state level, local legislators nationwide have engaged in a similar set of oppositional strategies. In 2019 Oregon, Republicans fled the state, successfully blocking gun control and vaccine bills, and in Pennsylvania, Republicans defied procedure by refusing to swear in a reelected senator; these events suggest that the political model used in Wisconsin in 2011 has been replicated.Footnote 103 Future analyses of the dynamics underpinning these politicians’ struggle for control could enrich understanding of institutional change and its consequences for democracy.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Ed Walker, Rebecca Emigh, Bill Roy, Eleni Skaperdas, Jonah Stuart Brundage, Gabriel Rossman, Zach Griffen, Andrew Herman, Kyle Nelson, Kevin Shih, Pei Palmgren, and David Coles, who provided feedback on multiple drafts on this article. Many thanks also to the Contentious Politics and Organizations Working Group (now called Movements, Organizations, and Markets) at UCLA and the reviewers at Studies in American Political Development for their very helpful comments.