Introduction

Small businesses are often considered the backbone of economic growth and the main contributor to employment in developing and developed countries. Despite their importance, access to funding is fairly restricted to these businesses (European Commission 2021; FI-Compass 2019). This so-called funding gap has several well-accepted causes including information asymmetries and transaction costs (Beck and Demirguc-Kunt Reference Beck and Demirguc-Kunt2006; Carnevali Reference Carnevali2005; Cressy Reference Cressy and Cumming2012; Cull et al. Reference Cull, Davis, Lamoreaux and Rosenthal2006; Ross Reference Ross1996). Households that rely on credit to cover setbacks in revenues and expenses fare even worse (Baradaran Reference Baradaran2015; Caskey Reference Caskey1994; Collins et al. Reference Collins, Morduch, Rutherford and Ruthven2009; Morduch and Schneider Reference Morduch and Schneider2017; Servon Reference Servon2017; Wright Reference Wright2019). Even today, the number of underbanked adults who have limited or no access to credit or financial services more generally is estimated to be 1.7 billion (Demirgüç-Kunt et al. Reference Demirgüç-Kunt, Klapper, Singer, Ansar and Hess2020). The COVID-19 pandemic, which has adversely impacted vulnerable groups, has only worsened this (Gutiérrez-Romero and Ahamed Reference Gutiérrez-Romero and Ahamed2021).

Financial inclusion initiatives set out to address these funding gaps and aim to bolster economic growth by providing small businesses and households universal access to credit as well as a wide range of other useful and affordable financial services (UNSGSA 2021). While inclusive finance – of which microcredit is an important part – is a relatively novel concept, municipal pawnshops (Calder Reference Calder2001; Carboni and Fornasari Reference Carboni, Fornasari, Cantaluppi, Colchester, Costabile, Hofmann, Schenk and Weber2020; Maassen Reference Maassen1994; McCants Reference McCants2007; Tebbutt Reference Tebbutt1983; Woloson Reference Woloson2007, Reference Woloson2009), cadastral systems (Van Bochove et al. Reference Bochove, Deneweth and Zuijderduijn2015), preprinted loan contracts (Van Bochove and Kole Reference Bochove and Kole2014), and specialized intermediaries (Hoffman et al. Reference Hoffman, Postel-Vinay and Rosenthal2000, Reference Hoffman, Postel-Vinay and Rosenthal2019; Van Bochove and Van Velzen Reference Bochove and van Velzen2014; Verwaaij and Van Bochove Reference Verwaaij and van Bochove2019) already made credit markets more inclusive during medieval and early modern times. As a consequence, sizeable and developed credit markets existed in the towns and countrysides of Europe and North America (Briggs and Zuijderduijn Reference Briggs and Zuijderduijn2018; Dermineur Reference Dermineur2018; Middleton Reference Middleton2012; Ogilvie et al. Reference Ogilvie, Küpker and Maegraith2012; Schofield and Lambrecht Reference Schofield and Lambrecht2009; Vickers Reference Vickers2010).

The organization of credit markets came under pressure during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as economic and social development changed urban and rural societies’ demand for credit and altered their ability to secure it. In rural areas, credit cooperatives – or so-called Raiffeisen banks – emerged to tackle these challenges and even today these are still one of the most enduring and prevalent forms of organized small-scale credit in the world (Guinnane Reference Guinnane, Armendáriz and Labie2011; Hollis and Sweetman Reference Hollis and Sweetman1998a). Precisely for this reason, a substantial literature, spearheaded by Guinnane and coauthors, has focused on rural credit cooperatives (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Besley and Guinnane1994; Ghatak and Guinnane Reference Ghatak and Guinnane1999; Guinnane Reference Guinnane1997, Reference Guinnane2001, Reference Guinnane, Armendáriz and Labie2011). Guinnane’s main contribution has been to demonstrate that rural credit cooperatives – established within close-knit local communities – were able to screen loan applicants, monitor outcomes, and enforce repayments with relatively low costs by relying on social capital and joint liability. As such, these institutions were able to overcome issues related to moral hazard and adverse selection, which plague small-scale lending, and which prevented conventional banks from reaching out to the rural poor. Later scholars strengthened the analysis of Guinnane by demonstrating that credit cooperatives’ business form also allowed them to adjust to local circumstances and to weather financial distress (Colvin Reference Colvin2017) and by analyzing the variables that drove the spread, success – or lack thereof – and evolution of rural credit cooperatives (Colvin et al. Reference Colvin, Henderson and Turner2020; Suesse and Wolf Reference Suesse and Wolf2020).

As we will demonstrate in more detail throughout this paper, the history of the urban counterparts to rural credit cooperatives is either less researched or the scholarship is simply less well known. One thing that is clear, though, is that urban credit cooperatives were often less successful than their rural counterparts in reducing poverty through access to credit (Guinnane Reference Guinnane1997: 254; Reference Guinnane, Armendáriz and Labie2011: 84). As the demand for credit by small businesses and households persisted, this raises the question what institutions instead developed in the towns that had proved so creative in developing more inclusive credit markets during the medieval and early modern periods.

Through a close reading of scattered, disparate, and largely unconnected secondary sources, supplemented with the analysis of primary sources, and backed by economic theory, this paper finds that in towns across Europe and North America, so-called small-scale credit institutions – a term coined by Wadhwani (Reference Wadhwani, Cassis, Grossman and Schenk2016) – could be found that shared a reliance on loan cosigners, or guarantors, to secure loans and weekly instalments to repay them. We call them cosignatory lending institutions or CLIs. Throughout this paper, we will demonstrate that, just like credit cooperatives, these institutions provided small loans. Credit cooperatives, however, relied on a stronger form of loan securitization (which held all members of the cooperative accountable via joint liability) and less frequent instalments (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Besley and Guinnane1994). Also, like credit cooperatives, CLIs’ shared lending format was flexible enough to display regional variations (Colvin and McLaughlin Reference Colvin and McLaughlin2014).

We show that the cosignatory lending format worked in societies characterized by notable differences in wealth and economic structure. The institutions that used it thrived as loan funds in Ireland, Morris Plan banks in the United States, Hebrew Free Loan Societies in Europe, Canada, and the United States, and help banks (hulpbanken) in the Netherlands.Footnote 1 Although their origins date back to even earlier periods, many of these institutions were introduced throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and continued to play an important role in local financial markets well into the twentieth century. The ancient roots of some of the CLIs suggest that searching for solutions to meet demand on credit markets is a historical constant. Moreover, it shows that CLIs seemed capable of offering a sustainable solution for the growing demand for small-scale credit in towns. This paper thus goes further than Carruthers et al. (Reference Carruthers, Guinnane and Lee2012), Guinnane (Reference Guinnane, Armendáriz and Labie2011), and Guinnane and Henriksen (Reference Guinnane and Henriksen1998) who recognized CLIs as a functional alternative to credit cooperatives, but did not identify them as a broader movement and institutional innovation.Footnote 2

Like Banerjee et al. (Reference Banerjee, Besley and Guinnane1994), Guinnane (Reference Guinnane, Armendáriz and Labie2011), and Hollis and Sweetman (Reference Hollis and Sweetman1998a, Reference Hollis and Sweetman2001) we argue that the challenges faced and solutions tried by CLIs are similar to those of financial inclusion initiatives today. Precisely for this reason, Hollis and Sweetman (Reference Hollis and Sweetman1998a: 1888) called it “inappropriate” not to draw lessons from these historical parallels. Therefore, we believe that, while keeping a keen eye for differences in contexts, it is possible to draw lessons from the history of CLIs that are applicable to present-day, financially-inclusive institutions (Bátiz-Lazo and Billings Reference Bátiz-Lazo and Billings2012; Caprio and Vittas Reference Caprio, Vittas, Caprio and Vittas1997; Cassis et al. Reference Cassis, Grossman and Schenk2016; Mersland Reference Mersland2011; Wadhwani Reference Wadhwani, Cassis, Grossman and Schenk2016; Woolcock Reference Woolcock1999). This is important because, similar to these historical institutions, contemporary initiatives to make financial markets more inclusive are often concentrated in towns.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides context by discussing the theory of cosignatory lending institutions. By focusing on the cosignatory lending model, we can start to recognize a broader movement of institutions that applied it and better understand the diversity in historical credit markets. Section 3 then addresses the commonalities and differences between the cosignatory and cooperative lending formats. It also lays out why cosignatory lending was more effective in towns than in the countryside and why CLIs formed a distinct institutional type. Section 4 traces the roots of CLIs into the early modern period and establishes a link between CLIs operating under different names in different places and times. Despite such variation, CLIs were remarkably similar in terms of their location, clients, and loans. They represented a broad movement and made a positive socio-economic impact by forming an important source of credit to local communities. Finally, Section 5 summarizes, concludes, and offers avenues for further research.

Theory of cosignatory lending institutions

Credit risk is the possibility of a loss resulting from a borrower’s failure to repay a loan or meet contractual obligations (Crouhy et al. Reference Crouhy, Galai and Robert2000). One way to reduce the odds and consequences of borrowers not meeting their obligations is to seek security over some assets of the borrower. Such collateralization of assets offsets the risk of default because it permits the lender to seize and sell the asset (Cerqueiro et al. Reference Cerqueiro, Ongena and Roszbach2016). Precisely for that reason, peer-to-peer and pawnshop lending have relied on collateral for centuries (Van Bochove and Kole Reference Bochove and Kole2014; Gelderblom and Jonker Reference Gelderblom and Jonker2004; Maassen Reference Maassen1994; Tebbutt Reference Tebbutt1983; Woloson Reference Woloson2007, Reference Woloson2009). The drawback of loan collateralization, though, is that small-scale borrowers often lack sufficient assets to offset the credit risk or cannot do without such assets (e.g. equipment and company stock) in their businesses or households (Beck and Demirguc-Kunt Reference Beck and Demirguc-Kunt2006).

More inclusive credit institutions such as credit cooperatives therefore tend to secure loans by relying on cosigners, who could be held responsible for the loan amount and any additional fees if borrowers defaulted (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Besley and Guinnane1994). Cosigning a loan thus involved the possibility of a real economic loss to the cosigner. Cosigners with positive net wealth would only accept this risk if they believed borrowers to be trustworthy and likely to repay loans. According to Banerjee et al. (Reference Banerjee, Besley and Guinnane1994) and Mushinski and Philips (Reference Mushinski and Phillips2001, Reference Mushinski, Phillips, Yago, Barth and Zeidman2008) the borrower’s ability to find cosigners hence provided a strong signal of being what they refer to as a “high-type” or low-risk borrower. They theorized that this assortative matching mechanism enabled lenders to distinguish and separate groups composed (almost) entirely of “high-type” borrowers and groups composed (almost) entirely of “low-type” or high-risk borrowers. This mechanism, in turn, made screening, monitoring, and enforcing easier and cheaper for lenders (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Besley and Guinnane1994; Ghatak and Guinnane Reference Ghatak and Guinnane1999; Guinnane Reference Guinnane2001, Reference Guinnane, Armendáriz and Labie2011; Mushinski and Phillips Reference Mushinski and Phillips2001, Reference Mushinski, Phillips, Yago, Barth and Zeidman2008).

Like posting collateral, cosigning was a convenient and widely-used way of securing credit. It was used in bills of exchange, accommodation paper, and in regular loans. In large and developed credit markets, like eighteenth-century Amsterdam, cosigned (as well as collateralized) loans were so frequently made that stationers even sold preprinted forms for recording them (Van Bochove and Kole Reference Bochove and Kole2014). The drawback of using cosigners, however, was that it hinged on cosigners to be well acquainted with borrowers to be able to apply (non-)economic sanctions to pressure them into repaying their loans when necessary and capable of repaying loans themselves in case of default. While borrowers’ ability to provide cosigners was important, it thus remained imperative for lenders to carefully assess cosigners and their relationship to borrowers (Besanko and Thakor Reference Besanko and Thakor1987; Bond and Rai Reference Bond and Rai2008).Footnote 3

Despite the benefits of cosigners, not all borrowers could identify suitable lenders – especially when borrowers belonged to homogeneously cash-strapped groups – and not all lenders could easily and cheaply verify borrowers’ cosigners. Similar problems existed in collateralized borrowing, but whereas (municipal) pawnshops successfully solved them by providing collateralized loans on an institutional basis across Europe (Maassen Reference Maassen1994; Tebbutt Reference Tebbutt1983) and North America (Calder Reference Calder2001; Woloson Reference Woloson2007, Reference Woloson2009), something similar did not happen as early with cosigned loans. Ordinary people in urban and rural societies consequently had to turn to less desirable loan types instead or had to refrain from borrowing altogether.

To fill this lacuna – and considerably earlier than the more well-known credit cooperatives established from the mid-nineteenth century onwards – a new type of small-scale credit institution was introduced in the early modern period: the cosignatory lending institution.Footnote 4 This paper will demonstrate in detail that CLIs shared several core features. They were specifically designed to issue small-scale loans (but could provide larger ones) at relatively low annualized percentage rates (APRs). Their propagators realized that the challenge resided in how such loans could be provided efficiently and in a borrower-friendly way. A combination of two solutions helped achieve this. To reduce repayment problems, loans were tallied to borrowers’ possibilities: they were granted for fairly lengthy periods of time – usually one year but especially in later periods also up to two years – and had to be repaid in weekly instalments.Footnote 5 Borrowers who repaid loans in time were rewarded, while those who failed to do so were fined. Combining this with a reliance on the social ties within local communities further reduced risks for CLIs. Only requiring cosigners to secure loans thus proved to be another effective way to screen and monitor borrowers and mitigate problems with loan repayments.Footnote 6

A comparative perspective on small-scale credit institutions

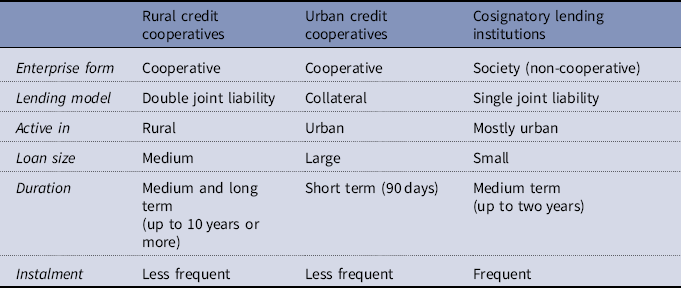

Equipped with a better understanding of how CLIs and the cosignatory lending format functioned in theory, we compare CLIs to the related but better-known credit cooperatives and their cooperative lending format. Such comparison clarifies why CLIs formed a distinct institutional type and deepens our understanding of why cosignatory lending was comparatively more effective in towns than in the countryside. Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of CLIs and credit cooperatives, and Figure 1 visualizes the institutional differences. Together, they provide a good starting point for a more in-depth discussion.

Table 1. Stylized characteristics of credit cooperatives and cosignatory lending institutions

Source: See text.

Note: Based on the schema used in Colvin et al. Reference Colvin, Henderson and Turner2020; Colvin and McLaughlin Reference Colvin and McLaughlin2014; Hollis and Sweetman Reference Hollis and Sweetman1998a.

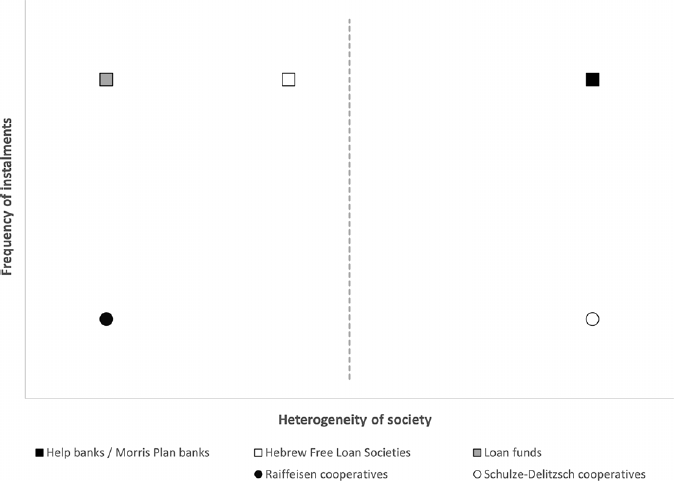

Figure 1. CLIs and credit cooperatives compared

Source: See text.

Notes: The squares represent types of CLIs that could be found in different types of environments, but as small differences existed within each type of CLI it should be reminded that clouds of squares scattered around each of the current squares would have been a more accurate representation. This point also applies to the credit cooperative dots (Colvin Reference Colvin2017; Colvin and McLaughlin Reference Colvin and McLaughlin2014; Guinnane Reference Guinnane1994, Reference Guinnane, Armendáriz and Labie2011).

We start by looking at the similarities between CLIs and credit cooperatives and then look at the differences. For completeness’ sake, we distinguish between rural and urban cooperatives and compare both with CLIs. Like CLIs, rural credit cooperatives were founded to help small businesses and households to raise their incomes through small but productive investments (Colvin and McLaughlin Reference Colvin and McLaughlin2014). They also relied on local elites for volunteer labor to keep transaction costs low and they likewise did not rely on collateral but instead on cosigners to secure most of their loans (Ghatak and Guinnane Reference Ghatak and Guinnane1999: 212). Urban credit cooperatives, also referred to as Schulze-Delitzsch banks, named after their founding father Franz Hermann Schulze-Delitzsch, existed alongside rural credit cooperatives but received much less scholarly attention. They operated similarly to their rural counterpart but seemed to have been less successful in making credit markets more inclusive (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Besley and Guinnane1994: 495–497; Guinnane Reference Guinnane1997: 254; Reference Guinnane, Armendáriz and Labie2011: 84).

Despite their many similarities, CLIs and credit cooperatives (both urban and rural) also crucially differed from one another. The first distinction between these institutions, illustrated by the vertical axis in Figure 1, is the frequency of instalments. CLIs relied on frequent instalments and are therefore placed towards the top of Figure 1. In comparison, credit cooperatives had a significantly lower repayment frequency, hence the lower placement of credit cooperatives (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Besley and Guinnane1994).

A more notable difference is the way in which these institutions secured their loans. CLIs relied on a more straightforward system of cosigning, whereby borrowers were required to bring cosigners who would be held accountable in case of default. As discussed in the previous section, this lending model made screening, monitoring, and enforcing easier and cheaper, which allowed CLIs to be more inclusive.

As argued by, for instance, Banerjee et al. (Reference Banerjee, Besley and Guinnane1994), Ghatak and Guinnane (Reference Ghatak and Guinnane1999), and Guinnane (Reference Guinnane2001, Reference Guinnane, Armendáriz and Labie2011), credit cooperatives relied on a more elaborate system of securing loans, which is known as joint liability. In this lending model, not only the cosigners of a specific loan but also all cooperative members may be held accountable. In other words, the credit cooperatives’ practice of joint liability essentially involved a larger group of cosigners in the process of assortative matching. In case of default, borrowers faced social sanctions from a broader and more diverse group, which also stood to lose economically through its share in the cooperatives’ capital and the deposits it may have held there. As both of these channels improved cooperatives’ ability to select trustworthy borrowers, they could offer their members better loan conditions and, in some cooperatives, dividend payments (Ghatak Reference Ghatak1999; Ghatak and Guinnane Reference Ghatak and Guinnane1999; Guinnane Reference Guinnane2001; Mushinski and Phillips Reference Mushinski, Phillips, Yago, Barth and Zeidman2008).

Joint liability thus offered benefits to members but also introduced additional risks. Risk-averse individuals were, of course, only willing to accept the additional risk that came with membership of a cooperative when they personally knew the other members, could assess the nature of the investments they planned, and were able to punish bad behavior (Mushinski and Phillips Reference Mushinski, Phillips, Yago, Barth and Zeidman2008: 132–137). Consequently, not only would joint liability lending in an urban context – where members had less knowledge of each other’s businesses and personal traits – be less effective; it would also be less desirable (Guinnane Reference Guinnane1997: 254). To put it in layman’s terms, individuals with little in common would simply not be willing to rely on mutuality: the risks would exceed the benefits. As a consequence, urban credit cooperatives came to rely less on cosigning and joint liability and more on traditional lending practices – in particular the use of collateral – and became more akin to commercial banks (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Besley and Guinnane1994; Guinnane Reference Guinnane1997, Reference Guinnane, Armendáriz and Labie2011). They were thus also less successful in reducing poverty through access to credit as they increasingly favored their wealthier clientele – that had access to collateral – at the expense of poorer ones (Engels Reference Engels2009: 24–25; Hermes and Lensink Reference Hermes and Lensink2011).

Figure 1 clarifies this insight through the arbitrarily placed dashed vertical line that differentiates environments that were homogeneous enough for the joint liability of credit cooperatives (i.e. to the left of the line) from environments that were too heterogeneous for this (i.e. to the right of the line). The countryside, with its small, tight-knit, and stable communities and less-varied occupational structure, formed a more homogeneous environment than towns and was hence better suited for the joint liability of credit cooperatives. This helps explain why rural credit cooperatives were more successful than urban credit cooperatives (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Besley and Guinnane1994: 495–497; Guinnane Reference Guinnane1997: 254; Reference Guinnane, Armendáriz and Labie2011: 84). The simpler cosignatory lending model of the CLIs was more suited in towns and did a better job there in reaching small businesses and households than the urban credit cooperatives with their joint liability lending model.

We argue, however, that this did not preclude CLIs and urban credit cooperatives from serving more homogeneous environments, such as the countryside (in the case of CLIs) or specific occupational or religious groups in towns (in the case of urban credit cooperatives). Here, it should be remembered that joint liability was a mid-nineteenth-century invention: CLIs had been operating long before the cooperative form was introduced to credit markets. This helps understand why CLIs also operated in the countryside and why they did not change their liability regime or why credit cooperatives could not replace them there, as Colvin and McLaughlin (Reference Colvin and McLaughlin2014) suggest may have been the case in Ireland. Processes of path-dependency (i.e. custom) may also explain why, long after the introduction of the cooperative form, CLIs were still established in small religious communities, as happened with the Hebrew Free Loan Societies in the United States. It should not be lost out of sight either that in some cases, such as that of the Jewish population of New York City, the size of a religious group – and accordingly: its heterogeneity – will have complicated the use of the cooperative form.

The foregoing showed that borrowers always had to weigh costs and benefits: in credit markets, benefits never come without (additional) liabilities. This is why, even though CLIs and credit cooperatives both relied on cosigners, they formed two distinct types of small-scale lenders – a distinction that nineteenth-century observers in the Netherlands also made (Fokker Reference Fokker1872a, Reference Fokker1872b, Reference Fokker1873; Goeman Borgesius Reference Goeman Borgesius1872; Voorschot-vereenigingen 1872) – and why it is not very meaningful to ask which of the two was the best. Each was simply suited best to particular historical environments.

Socio-economic impact of cosignatory lending institutions

This section builds on our theoretical analysis and assesses the socio-economic impact of CLIs by looking more closely at three aspects. It will be demonstrated that CLIs had early modern roots and remained relevant well into the twentieth century. They could be found around the globe but were mainly active in urban areas. There, CLIs improved access to small loans to borrowers with diverse occupational backgrounds and various reasons for requiring such loans.

History of cosignatory lending institutions

The earliest traces of CLIs are available for Jewish communities, such as Amsterdam’s Sephardim, who established the Honen Dalim loan society in 1625. Guided by religious principles, the society charged no interest on its loans. Although the society initially provided small loans on collateral only, it later also offered cosigned loans (Bernfeld Reference Bernfeld2012; Da Silva Rosa Reference Da Silva Rosa1925). This likely started before 1739, the year in which London’s Sephardim – who copied most of their practices and institutions from Amsterdam – first discussed the establishing of a CLI (Lieberman Reference Lieberman, Lieberman and Jan Rozbicki2017, Reference Lieberman2019). The Amsterdam CLI survived the hand of time, and during the 1850s there even were two Jewish CLIs in Amsterdam: one for the Sephardim and the other probably for the Ashkenazim. At this time, Jewish CLIs also existed in Arnhem, Groningen, Leeuwarden, and The Hague. They were all funded by gifts and members’ contributions and they were considered the philanthropic version of the secular help banks discussed below (Fokker Reference Fokker1872a; Onze Hulpbanken 1862).

The Ma’asim Tovim society, the first CLI established by the London Sephardim, was founded in 1749 and was also funded through gifts and members’ contributions. It provided interest-free loans of up to ₤5 for productive purposes. Loans were secured by cosigners or collateral and instalments had to be made regularly. Those who defaulted on their loans were excluded from receiving charity (sedaca) (Lieberman Reference Lieberman, Lieberman and Jan Rozbicki2017, Reference Lieberman2019). During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, very similar institutions operated across England. The Jewish Board of Guardians in London and Manchester are examples of this (Black Reference Black1988; Godley Reference Godley1996; Lipman Reference Lipman1959). In Manchester, immigrants from Eastern Europe established the Russian Jews’ Benevolent Society (1905) – renamed into Manchester Jews’ Benevolent Society in 1911 – for providing exactly the same type of loans (Liedtke Reference Liedtke1998a, Reference Liedtke1998b).

Jewish communities founded CLIs based on the same motivation and principles in Germany, Poland, and Russia as well (Tenenbaum Reference Tenenbaum1993). The first Jewish CLI in Germany was established in Landsberg an der Warthe (now Gorzów Wielkopolski in Poland) in 1813 and a second CLI followed in Hamburg in 1816 (Vorschuss-Institut). A similar but short-lived Christian institute had been founded in Hamburg in 1796, but the Hamburg Jews do not seem to have taken their inspiration from it. During the twentieth century, and especially during the Interbellum, Jewish communities continued to establish CLIs (Darlehenskasse) in Germany (Bericht über das Vorschuß-Institut 1804; Fischer Reference Fischer2006; Kreutzmüller Reference Kreutzmüller2017; Liedtke Reference Liedtke1998a, Reference Liedtke1998b; Marcus Reference Marcus1934; Nathan Reference Nathan1916; Schwarz Reference Schwarz, Stascheit and Stecklina2013; Segall Reference Segall1915).

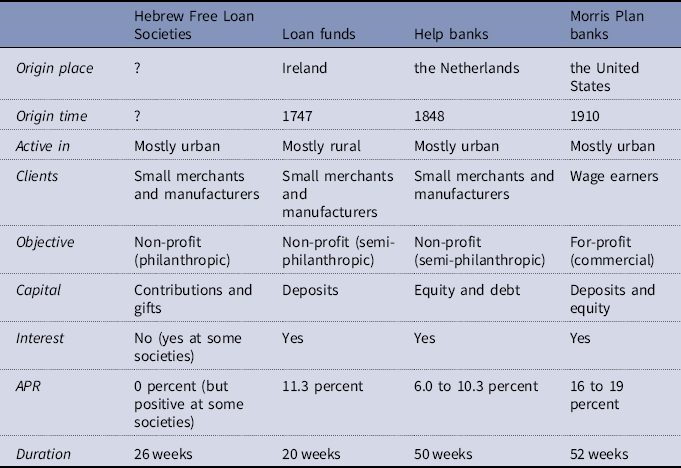

Once the Jewish diaspora from Eastern Europe reached North America, it established their CLIs there as well. As immigrants, most Eastern European Jews had little collateral for securing the small loans they regularly needed. Loans by family and friends were often unavailable or insufficient, whereas loans from pawnshops or loan sharks were expensive, and loans from commercial banks were inaccessible because loan applicants were too poor and did not speak the language (Day Reference Day2002). The first Hebrew Free Loan Society (hevrot gemilut hasadim) was established in Pittsburgh in 1887 and hundreds of similar societies in large and small communities across the United States would follow.Footnote 7 They were typically operated by volunteers, and by 1927 there were over 500 of them (Adelman Reference Adelman1954; Eisinger Reference Eisinger1977; Godley Reference Godley1996; Horvitz Reference Horvitz1978; Joselit Reference Joselit1992; Light Reference Light1984; Pitterman Reference Pitterman1980; Pollack Reference Pollack1988-1989; Pollak Reference Pollack2002: Rosen Reference Rosen1969; Segal Reference Segal1970; Tenenbaum Reference Tenenbaum1986, Reference Tenenbaum1989, Reference Tenenbaum1993, Reference Tenenbaum and Nadell2003). The most important of these, the Hebrew Free Loan Society of New York, was founded in 1892 by immigrants from Vilnius (then part of Russia). From its foundation until 1940, this society provided $32.7 million in over 671,000 loans. From 1920 onwards, it regularly disbursed over $1 million in loans per annum (Tenenbaum Reference Tenenbaum1993). Inspired by their success in Europe and the United States, Hebrew Free Loan Societies were also adopted in Montreal (Canada) in 1911. This first Jewish CLI in Canada lent almost $100 million to over 90,000 people (Guttman Reference Guttman2004; Taschereau Reference Taschereau2005, Reference Taschereau2006).Footnote 8

Another strand of CLIs found their origin during the 1720s with Jonathan Swift, author and dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin. According to his biographer Thomas Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1787: 234), Swift set out making loans “to poor industrious tradesmen in small sums of five and ten pounds, to be repaid weekly, at two or four shillings, without interest”. The sources cited by McLaughlin (Reference McLaughlin2009) suggest the Italian and Dutch pawnshops to have been Swift’s source of inspiration. A connection with these institutions seems unlikely, though, as they provided interest-bearing loans, secured by collateral, and repaid without weekly instalments (Bindon Reference Bindon1729; Madden Reference Madden1816). Footnote 9 In contrast, the striking similarities with the practices of the Jewish CLIs – cosigners, interest-free loans, and weekly instalments – make it tempting to conclude that Swift was inspired by these Jewish small-loan credit institutions.

While Swift still provided his loans on a peer-to-peer basis, the Dublin Musical Society was the first to institutionalize this practice in Ireland in 1747. Relying on the revenues of its concerts, this society offered interest-free loans to the poor. Other institutions followed the Musical Society’s example, but only during the first half of the nineteenth century did the number of CLIs start to increase considerably. There then existed three types of Irish CLI: loan fund societies and reproductive loan funds could be found in the countryside, whereas friendly society loan funds could be found in cities. Footnote 10 The loan fund societies were the most numerous of the three, and during the early 1840s a total of 553 of them operated across Ireland. In 1840, they combined for £474,538 in 130,044 loans (Goodspeed Reference Goodspeed2016, Reference Goodspeed2017, Reference Goodspeed2018; Hollis Reference Hollis, Lemire, Pearson and Campbell2002; Hollis and Sweetman Reference Hollis and Sweetman1998a, Reference Hollis and Sweetman1998b, Reference Hollis and Sweetman2001, Reference Hollis and Sweetman2004; McLaughlin Reference McLaughlin2009, Reference McLaughlin2013; McLaughlin and Pecchenino Reference McLaughlin and Pecchenino2019). Footnote 11 The nineteenth-century loan funds differed from Swift’s model in two ways: they obtained about 90 percent of their funding through deposits and they charged interest. Interest was discounted upfront and the annualized percentage rate averaged about 11.3 percent. This rate was kept in check by the fact that loan funds reduced operating costs by relying on the labor of unremunerated local elites (Hollis and Sweetman Reference Hollis and Sweetman1998b, Reference Hollis and Sweetman2001).

It were the rural Irish loan fund societies that Dutch social reformers, inspired by the new ideas of scientific philanthropy, turned to during the late 1840s when looking for ways of enabling industrious people without much capital (minvermogenden) to help themselves. Through an article in the French journal Annales de la Charité of 1847, the philanthropist W.H. Suringar became aware of the Irish loan funds that provided small loans. He subsequently propagated their introduction in the Netherlands, going so far as to also propose statutes for the Dutch equivalents, as he believed that credit would enable the underprivileged to get by on the basis of their own resourcefulness, thrift, and discipline (De Vicq and Van Bochove Reference De Vicq and van Bochove2021; Shepelwich Reference Shepelwich2002; Tenenbaum Reference Tenenbaum1993). Inspired by Suringar’s plea, the first help bank was established almost immediately. Dozens more followed, and by the late nineteenth century around 70 help banks operated across the Netherlands. Like their Irish counterparts, Dutch help banks (partially) relied on unremunerated local elites and discounted interest up front with rates of 3 to 5 percent or an annualized percentage rate of 6.0 to 10.3 percent. Contrary to the Irish loan funds, which relied heavily on deposits, the Dutch help banks primarily relied on equity and retained earnings. They probably kept from collecting deposits because dozens of savings banks across the Netherlands were already in this business (Dankers et al. Reference Dankers, van der Linden and Vos2001). Besides, local elites were large and wealthy enough to buy low-denomination shares.Footnote 12

In the United States, Arthur J. Morris took supplying small loans through cosignatory lending one step further by turning it into a for-profit business. His Morris Plan banks, the first of which was established in 1910, became America’s leading provider of small loans secured by cosigning (Barron Reference Barron1998; Barth et al. Reference Barth, Li, Angkinand, Chiang and Li2012; Herzog Reference Herzog1928: 19–21, 60–64; Mushinski and Phillips Reference Mushinski and Phillips2001, Reference Mushinski, Phillips, Yago, Barth and Zeidman2008; Saulnier Reference Saulnier1940: 72–83; Shepelwich Reference Shepelwich2002). As was the case with Swift’s initiative in Ireland, the Morris Plan too may have been based on Jewish CLIs. A few years after establishing the Morris Plan bank, Morris was taken to court by his former client David Stein, who claimed to have originated the CLI concept in 1898. Relevant for this paper is that the evidence presented in court revealed that Stein became familiar with the lending format in Russia (Trumbull Reference Trumbull2014; Universal Sav. Corp. v. Morris Plan Co. of New York et al. 1916). Given that Hebrew Free Loan Societies also flourished there, it is plausible that Stein copied their lending format. Footnote 13

As for-profit organizations, the Morris Plan banks could not rely on unremunerated workers. To turn a profit, they hence charged interest discounts that were higher than those of the semi-philanthropic Irish loan funds and Dutch help banks. Combined with the weekly instalments this meant that the annualized percentage rate of Morris Plan banks ranged between 16 and 19 percent. The fact that advertised interest rates (i.e. the discounts) concealed that actual borrowing costs (i.e. the annualized percentage rate) were much higher – a practice that was also common at the Dutch help banks – was criticized by contemporaries (Carruthers et al. Reference Carruthers, Guinnane and Lee2012; Fleming Reference Fleming2018; Guinnane Reference Guinnane, Armendáriz and Labie2011). Footnote 14 Whatever one makes of this, however, the Morris Plan banks’ annualized percentage rates compared well to the rates of pawnshops and loan sharks, which could reach as high as 300 percent (Calder Reference Calder2001: 48). Based on the rapid expansion of lending, moreover, Morris Plan banks must have filled a substantial niche: relying primarily on time deposits and deposits obtained by selling instalment certificates to borrowers, the 109 Morris Plan banks together lent about $220 million in 1931 (Mushinski and Phillips Reference Mushinski and Phillips2001, Reference Mushinski, Phillips, Yago, Barth and Zeidman2008). The success of the Morris Plan banks thus provides testimony to the effectiveness of CLIs in solving the problems inherent to the business of providing small loans.

Although demand for CLIs persisted well into the twentieth century, several developments led to their eventual demise. First, economic development reduced the demand for small loans. The consolidation of stores and workshops transformed a demand for small loans previously provided by CLIs into a demand for large loans and equity that other suppliers of funding could better provide. Stable jobs with higher and more regularly-paid wages likewise reduced the need for small emergency loans among laborers, but increased their demand for other financial products such as savings accounts and loans for durable consumer goods (Boter and Gelderblom Reference Boter and Gelderblom2022; Calder Reference Calder2001; Deneweth et al. Reference Deneweth, Gelderblom and Jonker2014). Second, the rise of the welfare state after World War II provided new solutions to the problems that small loans often sought to remedy. While unemployment benefits and old-age pensions helped mitigate reductions of income, the effects of unexpected shocks to expenditure were tempered by health insurance (Lindert Reference Lindert2004). Combined, these measures reduced the need for the small loans typically provided by CLIs. Third, new technologies reduced the transaction costs of banks, which helped them become better and more competitive in small-loan lending. As rising wages helped banks to attract more clients, the creation and storage of financial transaction data increasingly enabled banks to build records of the financial behavior of their clients (Lauer Reference Lauer2017). This facilitated a shift from relationship-based lending to transaction-based lending, which was further stimulated by the introduction of computer technologies after World War II. As these technologies were subject to economies of scale, banks gradually obtained further cost advantages over their competitors (Berger and Udell Reference Berger and Udell2006). This, then, better enabled banks to offer new forms of credit – such as the credit card – and provide some of the loans previously provided by CLIs.

CLIs across Europe and North America responded similarly to the challenges posed by these developments. One of their responses was to start offering new types of credit (such as consumer loans, student loans, and mortgages) or start serving new clienteles (as did the Hebrew Free Loan Societies, which substituted recently-immigrated Jews for clients who no longer required small loans) (Joselit Reference Joselit1992; Tenenbaum Reference Tenenbaum1993). However, CLIs dipping their toes in this market faced fierce competition and more often than not saw their number of clients dwindle due to almost exponential growth of instalment credit from the 1920s onwards. Realizing they were fighting an uphill battle, many CLIs had closed their doors by the late 1960s, and those that continued to operate did so more as remnant of a bygone age than as key providers of small loans – a point not missed by other researchers (Guttman Reference Guttman2004; Jacobs Reference Jacobs2005; Mushinski and Phillips, Reference Mushinski, Phillips, Yago, Barth and Zeidman2008; Taschereau Reference Taschereau2005, Reference Taschereau2006; Tenenbaum Reference Tenenbaum1989).

Location of cosignatory lending institutions

The most active Hebrew Free Loan Societies in the United States and Canada could be found in urban centers such as Boston, Chicago, Montreal, New York, and San Francisco. As their economies developed and industrialized, the populations of these cities grew rapidly and this created a demand for credit among consumers and producers alike. This is not to say, however, that Hebrew Free Loan Societies could not be found outside the centers of industry, commerce, finance, and transportation. Jewish CLIs were also established in smaller and more close-knit communities such as Altoona (Pennsylvania; 38,973 inhabitants), Elmira (New York; 35,672 inhabitants), Lafayette (Indiana; 18,116 inhabitants), and Shreveport (Louisiana; 16.013 inhabitants) (Bureau of the Census 1901: 447, 454, 464, 471; Tenenbaum Reference Tenenbaum1993).

Unlike the Hebrew Free Loan Societies, the Irish loan funds not only flourished in urban areas, but also in rural ones (McLaughlin Reference McLaughlin2013). What exactly was responsible for the latter is unclear, but it may be that Ireland’s economic underdevelopment and poverty had to do with it. Poor farmers possibly substituted credit secured by reputation (i.e. cosigned loans) for unsecured credit or credit secured by collateral. CLIs may also well have been their sole institutional resource to credit. By taking deposits and by providing small loans, the early rise of loan funds seems to have contributed to the floundering of credit cooperatives. The latter were introduced in Ireland relatively late and never became as successful as elsewhere in Europe (Colvin and McLaughlin Reference Colvin and McLaughlin2014; Guinnane Reference Guinnane1994). Footnote 15

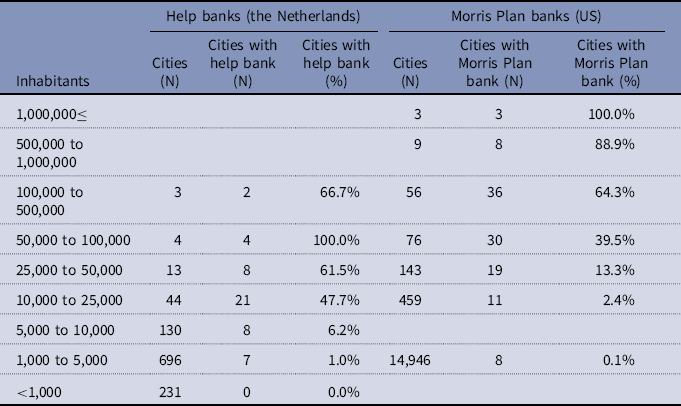

Data on help banks in the Netherlands corroborate the predominantly urban incidence of CLIs (see Table 2). Here too, it stands out that CLIs were well-represented in large cities. In smaller cities, they were all but absent. Given that help banks, like most other CLIs discussed in this paper, mainly targeted the laboring and lower middle classes and benefited from the philanthropic activities of well-endowed local elites, both of whom were more concentrated in urban areas, this pattern is not that surprising.

Table 2. Help banks and population sizes of all Dutch cities (1895) and Morris Plan banks (1926) and population sizes of all US cities (1920)

Source: Boonstra Reference Boonstra2016; Bureau of the Census 1921: 50, 178–319; Departement van waterstaat, handel en nijverheid 1897; Herzog Reference Herzog1928: 78–81.

Note: The source only specified the location of help banks that reported detailed data. As reporting help banks ranged from small to large, however, there is no reason to expect the Table to suffer from a reporting bias.

The fact that Morris Plan banks were for-profit CLIs means their distribution over US towns provides a purer insight into the economics of establishing CLIs. Herzog’s (Reference Herzog1928) list of all 115 cities that had one or more Morris Plan banks in 1926 is helpful here. Table 2 combines these data with population figures from the 1920 census. What again stands out immediately is the positive relationship between population size and Morris Plan bank incidence. All cities with more than one million inhabitants had a Morris Plan bank and all but one city with 500,000 to 1,000,000 inhabitants. Only some of the larger cities had more than one office and in rural communities and very small cities they were virtually absent. This point was not missed by Herzog (Reference Herzog1928: 77–82), who commented that Morris Plan banks were present in most of the leading manufacturing cities, but absent where industrial development or favorable state law were lacking. Interestingly, the threshold for Morris Plan banks to be established in the US was higher than for help banks to be founded in the Netherlands. This suggests that for-profit CLIs required a larger market than non-profit CLIs.

Lending practices of cosignatory lending institutions

CLIs improved access to a part of the population that otherwise struggled with gaining entry to credit markets at reasonable terms. This is illustrated, among others, by the diversity of the occupations of CLIs’ borrowers. The Hebrew Free Loan Society of New York (1914), for instance, listed 138 occupations in its annual report for 1914. In general, about one-third of Hebrew Free Loan Societies’ borrowers consisted of artisans and other laborers. The other two-thirds consisted of storekeepers, peddlers, jobbers, contractors, butchers, teachers, booksellers, and farmers, among others. While borrowers were mostly of (Eastern European) Jewish origin, more than 15 percent of all loans were granted to non-Jews (Guttman Reference Guttman2004). Loans were usually made for productive purposes, such as starting, continuing, or expanding a business, but sometimes they were also used for financing personal expenditures (Tenenbaum Reference Tenenbaum1989). It is important to note here that imposing a present-day, clear-cut distinction between producer and consumer credit to the past is somewhat of an anachronism. The vast majority of businesses were one-person enterprises and there was hardly any separation between personal and business capital. Many goods and machinery funded with borrowed money served both productive as well as consumptive means. Conversely, loans aimed for consumption-smoothing purposes could be used to free up capital, thus serving more productive investments (Lemercier and Zalc Reference Lemercier and Zalc2012).

The main clients of the Irish loan funds were small farmers, weavers, spinners, dealers, and laborers. Their loans typically were productive as well and projects included the purchase of dairy cows, pigs, sheep, tools, or inventory. However, loans were also used to pay for rent or to purchase food in bulk (Hollis and Sweetman Reference Hollis and Sweetman1998b, Reference Hollis and Sweetman2001). Borrowers who most commonly used the Dutch help banks were laborers, sales workers (in particular small merchants, grocers, and shopkeepers) and, more generally, farmers or agricultural workers. A case study of the Nijmegen help bank identified around 200 occupations in loans made during the period 1871–1939. Approvable credit applications included but were not limited to the purchase of basic machinery (e.g. sewing equipment), fuel (e.g. coal and peat), raw materials needed to create manufactured goods (e.g. cloth and leather), or final goods which could be sold at a profit. Sometimes, loans were used to purchase shop inventories (e.g. fruit and vegetables) in bulk and in rare occasions even to pay for rent arrears, tuition fees, and bail (De Vicq and Van Bochove Reference De Vicq and van Bochove2021).

Morris Plan banks likewise lent to borrowers in a wide range of occupations. The Morris Plan bank of Detroit, for example, observed over 400 different occupations among its borrowers in 1926 (Herzog Reference Herzog1928: 93). Morris Plan bank borrowers primarily were low- and middle-income individuals who could not obtain loans from commercial banks. Reports of the Morris Plan Company of New York reveal that, during the first eight months after its establishment, borrowers were mostly clerks, state officials, salesmen, and bookkeepers (Herzog Reference Herzog1928: 91–93). More mature Morris Plan banks and such CLIs in other cities – where government jobs were less common – seem to have attracted primarily clerical workers and wage earners who needed credit to cover unexpected events. Others borrowed in order to begin or expand their businesses (Mushinski and Phillips Reference Mushinski and Phillips2001, Reference Mushinski, Phillips, Yago, Barth and Zeidman2008; Neifeld Reference Neifeld1941; Saulnier Reference Saulnier1940: 131–133).

Generalizing from the foregoing is complicated by the sources which often described jobs rather casually, did not specify the occupation of women, and contained large groups of miscellaneous occupations. Nevertheless, the historical international classification of occupations (HISCO) system can be used to identify some patterns in the relative importance of large occupational groups (Van Leeuwen et al. Reference Leeuwen, Maas and Miles2002). This reveals that while borrowers from all occupational groups could be observed, most loans were provided to occupational groups 4 (‘sales workers’) and 7/8/9 (‘production and related workers, transport equipment operators and laborers’). As indicated above, occupational group 3 (‘clerical and related workers’) was important in New York as well (Herzog Reference Herzog1928: 92–93; Saulnier Reference Saulnier1940: 131–133). Occupational group 6 (‘agricultural, animal husbandry and forestry workers, fishermen and hunters’) was relatively important in Ireland (Hollis and Sweetman Reference Hollis and Sweetman1998b: 361; Reference Hollis and Sweetman2001: 302). The same applied to the help bank of Nijmegen (Nijmeegse hulpbank 1870-1952: selected years during the period 1871–1939), but less to a set of help banks located in the more developed western part of the country: Haarlem (Haarlemse hulpbank 1855-1950), The Hague (Hulpbank te ’s-Gravenhage 1853-1954), and Utrecht (Jacobs Reference Jacobs2005, 52–53 for the year 1853). Footnote 16

All in all, the occupational data demonstrate that CLIs targeted notably heterogeneous occupational groups. With clients and loan purposes quite similar across CLIs, it is not surprising that the same applied to loan sizes and instalments. Loans were generally small, but still large enough to be economically significant to borrowers and instalments suited borrowers’ revenue streams (i.e. they were small but frequent). Average loans provided during the period 1892–1940 by the largest Jewish CLI in the United States, the Hebrew Free Loan Society of New York, ranged between $5 (1892) and $118 (1929). However, compared to the average loans of Jewish CLIs in other major American cities during the period 1925–37, average New York loans were always smaller than the sample average. Despite such regional variations and changes over time, the average loan of the whole sample only exceeded $100 in 1925. Loans typically had to be repaid in six months (Tenenbaum Reference Tenenbaum1993: 57, 64, 69). In Hamburg, Germany, average loans of the Jewish CLI ranged between 208 Mark ($50) and 354 Mark ($84) during the period 1875–1915 (Nathan Reference Nathan1916).Footnote 17

Loans issued by the Irish loan funds were significantly smaller. In 1843, the maximum loan size was £10 ($48), and the average loan at 298 loan funds then was £3.3 ($16), or a little less than the average per capita income (Hollis and Sweetman Reference Hollis and Sweetman1998a: 1879; Reference Hollis and Sweetman1998b: 355). Loans were repaid in 20 weekly instalments of equal size. As in the case of the Hebrew Free Loan Societies, clients who failed to keep to their repayment schedules could be excluded from borrowing for a certain period of time. Punctuality was further enforced by a system of fines for late payments. The fine for each overdue day amounted from 0.4 to 0.8 percent of the face value of the loan (Hollis and Sweetman Reference Hollis and Sweetman1998b).

The average loan of the Dutch help banks increased from 67 guilders ($27) in 1849 to 154 guilders ($62) in 1898, which equaled about a sixth to a third of the annual income of an industrial worker (De Vicq and Van Bochove Reference De Vicq and van Bochove2021). However, these averages hide the fact that a select few borrowers obtained much larger loans. At the Nijmegen help bank, for instance, the directors of a roof tile factory received loans of several thousands of guilders (Nijmeegse hulpbank 1870-1952: box 13 loan 527, box 14 loan 499, box 15 loans 322 and 406). Loans of such magnitude were, however, a very rare occurrence. The maximum duration of loans was in principle set at 50 weeks. Help banks’ borrowers were held to strict repayment schedules, typically with weekly instalments and, as an extra incentive, a discount if borrowers repaid ahead of time. Clients who failed to keep repayment schedules were penalized and excluded from borrowing for a certain period of time (Deneweth et al. Reference Deneweth, Gelderblom and Jonker2014; Geesink Reference Geesink1855). As was the case with the other CLIs, the remarkably low number of defaulting repayments (i.e. in almost all cases below one percent) show that this rarely happened (De Vicq and Van Bochove Reference De Vicq and van Bochove2021).

The loans issued by the Morris Plan banks averaged $126 in 1915 and $262 in 1926. During the period 1929–38, the average loans of a sample of ten Morris Plan banks ranged between $228 and $317. This meant that these loans equalled ten to twenty weeks of salary of an adult male. The formal lending scheme of Morris Plan banks was less straightforward than that of other CLIs. Loans typically had a maximum term of one year, but borrowers did not use their weekly instalments to redeem their loans directly and purchased certificates instead. When a loan matured, these certificates were exchanged for cash that was subsequently used to redeem the loan. As was the case in the other CLIs, defaulters were punished, but here too this was rarely necessary (Herzog Reference Herzog1928: 83; Mushinski and Phillips Reference Mushinski and Phillips2001, Reference Mushinski, Phillips, Yago, Barth and Zeidman2008; Robinson Reference Robinson1931; Saulnier Reference Saulnier1940: 85).

Table 3 summarizes the findings of this section by focusing on the main types of CLI, their key characteristics, and the (dis)similarities that existed in those.

Table 3. Overview of CLIs in Europe and North America

Source: See text.

Note: Based on the schema used in Colvin et al. Reference Colvin, Henderson and Turner2020; Colvin and McLaughlin Reference Colvin and McLaughlin2014; Hollis and Sweetman Reference Hollis and Sweetman1998a.

Conclusion

This paper started by exploring the economic theory behind credit risk and some common lending models, such as cosigning, aimed at reducing it (Beck and Demirguc-Kunt Reference Beck and Demirguc-Kunt2006; Cerqueiro et al. Reference Cerqueiro, Ongena and Roszbach2016; Crouhy et al. Reference Crouhy, Galai and Robert2000). It then argued how a newly-uncovered type of financial institution, we labeled them cosignatory lending institutions (CLIs), improved upon this lending model; thus allowing these institutions to issue small-scale loans at relatively low annualized percentage rates. CLIs achieved this by providing loans that suited borrowers (i.e. loans had terms that were long enough and were repaid through weekly instalments) and by implementing a system of carrot and stick (i.e. a reward for those who repaid in time and a fine for those who missed payments).

Next, the paper analyzed the main commonalities and differences between CLIs and the more well-known credit cooperatives. Based on a review of the theoretical work by Guinnane and coauthors (Ghatak Reference Ghatak1999; Ghatak and Guinnane Reference Ghatak and Guinnane1999; Guinnane Reference Guinnane2001) and Mushinski and Phillips (Reference Mushinski, Phillips, Yago, Barth and Zeidman2008) it was argued that while joint liability offered benefits it also introduced additional risks. It did so because risk-averse cooperative members accepted that risk solely because they were well familiar with the other members and their investment plans and could punish undesirable behavior. It was concluded that cosigning combined with joint liability among all credit cooperatives’ members was not the only effective model for lending small sums to small businesses and households. Cosigning combined with regular instalments sufficed as well. That lending model was particularly convenient in towns; precisely the location where CLIs were more common.

With a better understanding of how CLIs worked in theory, the paper then discussed the socio-economic impact of these institutions. A close reading of primary and secondary sources, informed by economic theory, confirmed that CLIs formed a distinct and important institutional type and demonstrated they thrived across Europe and North America as loan funds, Morris Plan banks, Hebrew Free Loan Societies, and help banks. These institutions were often introduced during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and remained important during a substantial part of the twentieth century.

By exploring how CLIs operated, developed, and improved access to credit, this paper deepened our understanding of the history of institutional arrangements that made credit markets more inclusive in urban contexts. And while this paper helped to address this lacuna, it could not cover all ground, and we hence identify three avenues for future research. First, collecting information about the presence of CLIs in locations not covered by this paper and the transplantation of CLIs from one place to the other. Second, analyzing how small businesses and households used peer-to-peer lending, pawnshops, banks, and both rural and urban credit cooperatives alongside or instead of CLIs. Third, assessing the impact CLIs had on the performance of small businesses and the welfare of households and, with that: the economy at large. We believe these three steps will contribute to a better understanding of the composition and evolution of the market for small loans. This will generate better insight into how access to small loans was improved, the historical circumstances that played a role in this, and perhaps even whether and how CLIs and their cosignatory lending format may be replicated in present-day developed and less-developed economies.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Chris Colvin, Oscar Gelderblom, Abe de Jong, Joost Jonker, Eoin McLaughlin, members of the Utrecht financial history group, the referees, and seminar participants at Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Utrecht University, the N.W. Posthumus Institute’s 2019 Annual Conference (Ghent) and the 13th Finance and History Workshop (Amsterdam) for helpful comments and suggestions.