Introduction

Europe’s long nineteenth century was characterized by an impressive rise in overall migration (Lucassen and Lucassen Reference Lucassen and Lucassen2009). Processes of demographic growth, proletarianization, mechanization, and the disintegration of rural livelihoods, fueled migration to cities and stimulated urban growth (Lees and Lees Reference Lees and Lees2007). At the same time, the marked expansion and improvement of means of communication and transport facilitated migration and mobility, allowing more people to move over longer distances (O’Rourke and Williamson Reference O’Rourke and Williamson2001). While the scale and direction of aggregate change during this so-called “mobility transition” (Zelinsky Reference Zelinsky1971) have been the subject of various studies, little is known about the evolution of migration flows from a social and spatial perspective. In this article, we investigate the social characteristics and spatial trajectories of international migrants to one booming European port city during the second half of the “long nineteenth century” to identify patterns of change in urban migration flows over time. We use this case study to argue and illustrate how the loosening connection between migration distance, social class, and gender, a process we call the democratization of long-distance migration, was one of the most momentous changes characterizing the unprecedented expansion of migration during the “mobility transition” of the long nineteenth century.

Migration selectivity and the mobility transition

Historical patterns of migration differed considerably according to age, gender, social position, and geographical background: migration is a selective, social process, which channeled particular groups to specific destinations (Moch Reference Moch2003). To account for this selectivity, Hoerder (Reference Hoerder, Lucassen and Lucassen1997) has drawn attention to the so-called micro-level and meso-level, next to structural macro-factors, to explain migration behavior. Macro-factors refer to societal characteristics that govern the spatial distribution of opportunities and constraints, such as employment, prices, and wages in economic terms, or persecution in political terms, while the micro-level refers to individual characteristics of migrants such as age, gender, skill, and wealth. In between stands the meso-level, i.e., the social networks and information channels at the disposal of (potential) migrants, which guide them in their migration decisions (Rosental Reference Rosental2006). A special case is that of chain migration, when relatives or co-villagers already resident elsewhere provide information and support to (future) migrants (Wegge Reference Wegge1998). Yet, migration also regularly took place without personal or family connections, guided by other channels of information, such as printed media, professional networks, recruitment agencies, travelers’ tales, or even gossip (Lesger Reference Lesger2006; Lesger et al. Reference Lesger, Lucassen and Schrover2002). Crucially, access to such personal and impersonal networks and information is socially selective, which helps to explain why and how different migrant groups adapted their behavior to changing circumstances in different ways and at different speeds (Winter Reference Winter2009).

Distance has long been a distinctive feature in migration selectivity. Like other spatial interactions, migration tends to be characterized by a distance-decay effect: other things being equal, the likelihood of migration between any two places declines as their distance increases (Fellman et al. Reference Fellman, Getis and Getis2003: 68–69). Yet, migration’s sensitivity to distance and “intervening obstacles” is socially selective, which can be related to differences in the relative costs and benefits of travel (Lee Reference Lee1966) and differential access to social networks and channels of information (Winter Reference Winter2009). Ravenstein’s (Reference Ravenstein1885: 196–99) so-called “laws of migration” observed as early as the late nineteenth century that women were as mobile as men but tended to move over shorter distances, while men dominated long-distance migration between cities (see also Alexander and Steidl Reference Alexander and Steidl2012). Likewise, Winter (Reference Winter and Clark2013) has likened urban immigration in early modern Europe to a social pyramid. Its broad base, gender-balanced or even female-predominant, consisted of short-distance, low-skilled, low-literate, and unspecialized rural migrants, whose continued influx was necessary to oil the brawn-intensive preindustrial urban economy (Clark Reference Clark, Clark and Souden1987; De Vries Reference De Vries1984: 199–210; Poussou Reference Poussou and Dupâquier1988). The top of this migration pyramid – its size determined by the city’s demand for skill – consisted of long-distance, predominantly male migrants who were better skilled, literate, and specialized, and mostly moved in interurban patterns of career migration (Groot and Schalk Reference Groot and Schalk2022: 211–14; Lesger Reference Lesger2006: 8–11, 19–20; Lucassen and De Vries Reference Lucassen, de Vries, Gayot and Minard2001; Luu Reference Luu2004). While the former depended primarily on diffuse channels of interpersonal, oral communication, which were most dense between a city and its direct hinterland, the latter had access to specialized, professional networks and information channels that covered longer distances (Kooij Reference Kooij, Menjot and Pinol1996: 200–201; Winter Reference Winter2009). More generally, the bulk of rural migration in early modern Europe took place over short distances, hence is dubbed “micro-mobility” rather than migration (Deschacht and Winter Reference Deschacht and Winter2019; Poussou Reference Poussou and Dupâquier1988), while migration over longer distances was predominantly interurban in character (Tilly Reference Tilly and McNeill1978).

The positive correlation between migration distance, urban background, and social status observed in early modern history, contrasts sharply with the image of low-skilled and ragged rural masses crossing long distances and even oceans in extensive numbers on the eve of World War I (Hoerder and Kaur Reference Hoerder and Kaur2013; McKeown Reference McKeown2004; Steidl Reference Steidl2021), when women too became more prominent in long-distance migrations within and from Europe (Donato and Gabaccia Reference Donato and Gabaccia2015; Gabaccia and Zanoni Reference Gabaccia and Zanoni2012; Schrover Reference Schrover, Hoerder and Kaur2013). In that respect, the long nineteenth century appears as a transition period during which the longstanding connection between migration distance and social status broke down, widening the migration horizons of millions of Europeans from modest backgrounds, a process that we propose to label the “democratization of long-distance migration.” In their quantitative study of European migration levels over the past five centuries, Lucassen and Lucassen (Reference Lucassen and Lucassen2009) conclusively debunked the myth of migration as a “modern” phenomenon of the nineteenth century and demonstrated long-standing involvement with migration since at least the sixteenth century. In this context, the real novelty of the “mobility transition” of the long nineteenth century was possibly not so much the observed increase in levels of mobility per se, as a restructuring and widening of existing patterns of mobility, transforming earlier processes of (short-distance) “micro-mobility” into (longer-distance) “migration” (cf. Deschacht and Winter Reference Deschacht and Winter2019).

At the macro-level, Europe’s Age of Mass Migration (Hatton and Williamson Reference Hatton and Williamson1998) was fueled by a fundamental restructuring of constraints – the increasing precarity of rural livelihoods – and opportunities – the proliferation of industrial and service jobs in cities home and abroad. Yet, the key to the emancipation from the impediment of distance that underlay the mass nature of migration were the many improvements in transport and communication technologies. These fundamentally altered the dynamics at the meso-level and allowed rural migrants to access information and support networks that transcended the regional hinterland of the nearest towns (De Block and Polasky Reference De Block and Polasky2011; Schepers et al. Reference Schepers, Polasky, Verhetsel, De Block, Blondé, Geens, Greefs, Ryckbosch, Soens and Stabel2020). Newer, faster, and more reliable overland and waterway connections via paved roads, railways, and steamships, and the strong competition between transport and travel agencies, fostered a noticeable decrease in travel cost (Feys Reference Feys2013; Martí-Henneberg Reference Martí-Henneberg2021; O’Rourke and Williamson Reference O’Rourke and Williamson2001: 35–36; Pooley Reference Pooley2017). At the same time, growing literacy rates, the proliferation and improved distribution of newspapers, postal services, telecommunications, and activities of recruitment agencies facilitated and democratized access to information (Crafts Reference Crafts1997: 305–7; Kaukiainen Reference Kaukiainen2001: 8–21; Wadauer et al. Reference Wadauer, Buchner and Mejstrik2012: 168–71; Wenzlhuemer Reference Wenzlhuemer2007). As these changes facilitated the movement of goods, information, and people, they significantly lowered the burden of distance and barriers to migration.

While long-distance migration in the nineteenth century has received attention primarily in the context of transatlantic migration (e.g., Harzig Reference Harzig1997), in this study we focus on analyzing the role of distance from a more inclusive, long-term perspective, allowing us to evaluate shifts over time in migration range. Several scholars have studied migration by specific groups, or to specific cities and regions during the age of mass migration (e.g., Green Reference Green1998; Hochstadt Reference Hochstadt1999; Jackson Reference Jackson1997; Pooley and Turnbull Reference Pooley and Turnbull1998; Steidl Reference Steidl2003, Reference Steidl2021), expanding our insight into the varied experiences of Europe’s mass migrants. While they enrich our understanding in many respects, no existing study explicitly tackles what we believe to be a central feature of Europe’s mobility transition, namely the declining social selectivity of distance. In this article, we combine a conventional analysis of urban migration streams in the second half of the long nineteenth century with a novel focus on the changing relationship between migration distance, social status, and gender. By analyzing individual data on c. 5,000 international migrants moving to the booming port city of Antwerp between 1850 and 1910, we aim to gain a better, differentiated understanding of the social and gender dimensions that contributed to the democratization of long-distance migration in the long nineteenth century.

Case study and sources

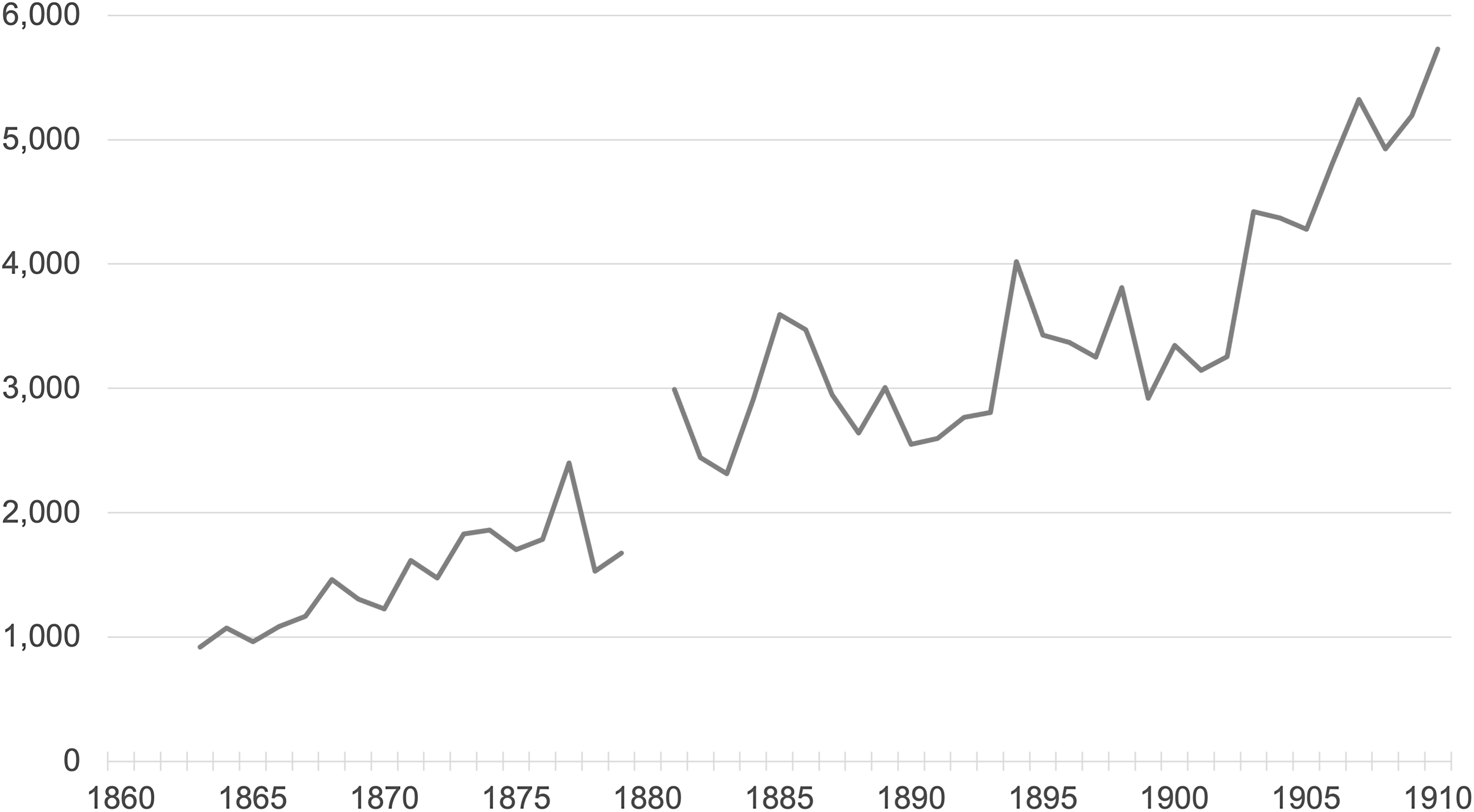

The city of Antwerp represents an interesting case for this study. During the second half of the long nineteenth century, the former regional textile town developed into a flourishing Atlantic port and trading center (Veraghtert Reference Veraghtert and Suykens1986). The city became a prime node in the Atlantic economy not only for the transshipment of goods but also for that of passengers with the establishment of the Red Star Line (1873), which would transport many hundreds of thousands of Europeans to America (Feys Reference Feys2013). New employment opportunities in the port economy, service sector, and port-related industries heightened its appeal to newcomers, as did processes of economic depression and proletarianization in its hinterland (Lis Reference Lis1986). Its population expanded rapidly from c. 100,000 mid-century to more than 300,000 on the eve of World War I, which officially made it the largest city of the Kingdom of Belgium. While Antwerp recorded some 5,000 newcomers per year in the 1850s – both national and international – this increased to more than 8,000 in the 1870s and 1880s and more than 20,000 in the first decade of the twentieth century. An important share of this growing number of newcomers came from abroad. Because of Belgium’s relatively small size and Antwerp’s location near the border, foreign newcomers extended from quasi-neighbors who had traveled less than 50 km, to those who had crossed continents and oceans. Annual published figures, available from 1864 onwards, show a steady increase in international migration over the period (Graph 1). Recorded immigration from abroad fluctuated around 1,000 in the early 1860s, increasing to around 3,000 to 4,000 in the 1890s, and surpassing 6,000 in the years leading up to World War I. Over the same period, the proportion of foreign nationals in the city’s overall population expanded from 6.82% in the 1856 census to 11.16% in 1910 (Greefs and Winter Reference Greefs, Winter, Blondé, Geens, Greefs, Ryckbosch, Soens and Stabel2020a; Statistique de la Belgique 1856–1910; Verslag over het bestuur en den zakentoestand der Stad Antwerpen 1865–1911).

Graph 1. Yearly number of Antwerp’s immigrants from abroad, 1863–1910.

Source: Verslag over het bestuur en den zakentoestand der stad Antwerpen, 1865–1911.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, international migration to Antwerp was dominated by male migrants who worked as merchants, clerks, and hospitality workers in the city’s expanding commercial firms, insurance companies, banks, shipbuilding companies, and bourgeois cafés and restaurants – i.e., a classic pattern of social selectivity in long-distance migration (Winter Reference Winter2009). A similar “elite” nature of foreign migration was also noticed in the capital city of Brussels in the same period (De Schaepdrijver Reference De Schaepdrijver1990). After observing that single foreign migration to Antwerp feminized considerably between 1850 and 1880 (Greefs and Winter Reference Greefs and Winter2016), we embarked on the current, more encompassing research endeavor in which we extend our time frame to 1910 and include all international newcomers, in order to make the evolution of the social selectivity of distance over time our prime focus.

The empirical basis of this study derives from Antwerp’s foreigners’ files (dossiers des étrangers), kept in the city archives from the 1840s onwards. For each foreigner who came to reside within a municipality of the Belgian state, a personal information form (bulletin de renseignements) had to be filled out by the local police, and forwarded to the national agency monitoring immigration, the Sûreté Publique (Caestecker Reference Caestecker2000). The bulletin contained answers to pre-printed questions on the identity (name, age, and sex), social and family background (parents, marital status, and occupation), and migration trajectories (place of birth and of last residence abroad and in Belgium) of the foreigner and his/her family, next to more lapidary information on judicial antecedents, reputation, or documentary status. Whereas the conservation of individual files at the state level has been patchy, especially for the years up to 1890 (Willems et al. Reference Willems, Strubbe and Heynssens2018), the local series of foreigners’ files have been conserved in their entirety in Antwerp.

The foreigners’ files were but one component of the precocious and laborious administrative infrastructure of population registration in nineteenth-century Belgium, which also included the civil registry of births, marriages, and deaths, 10-yearly population censuses, dynamic population registers, passport provisions and visa registration, and municipal demographic statistics including yearly immigration and emigration (Bracke Reference Bracke2008; Debackere Reference Debackere2020; Eggerickx and Sanderson Reference Eggerickx and Sanderson2010). Destined specifically for the registration of foreign residents who intended to stay for a while – the normative cut-off was longer than a fortnight – the foreigners’ files inherently exclude highly mobile and transitory groups, such as short-stay visitors, sailors, wanderers, or passengers waiting for departure.Footnote 1 Those who did fall within the scope of the foreigners’ files, mostly presented themselves for registration soon after arrival and on their own initiative, possibly prompted by landlords, acquaintances, employers, local constables, travel guides, and/or an internalized expectation of registration. The information noted down in the bulletin was verified on the basis of identity documents produced by the migrant, and/or inquiries with (previous) employers, landlords, or local authorities of previous places of residence. When foreigners arrived as a family unit, a bulletin was compiled only for the head of household, with mention of spouse and/or children. As far as we could gauge, registration did not entail any obvious disadvantages, except for those liable to be considered as vagrants or criminals. Although some intentionally or unintentionally evaded registration, the sheer volume of the bulletins des étrangers together with the city’s well-developed population administration, warrant that they were a small minority at most.Footnote 2 It is therefore safe to assume that the bulletins des étrangers recorded the lion’s share of all foreign migrants and can be taken as indicative of the evolution of foreign migration to Antwerp in this period.

We collected, cleaned, and analyzed all nominal data from the foreigners’ files for three sample years, 1850, 1880, and 1910, chosen to represent years not characterized by specific crisis contexts and at equal intervals to explore changes over time (henceforth DFFA, Database Foreigners’ Files Antwerp, 1850–1910).Footnote 3 This resulted in a total sample of 5,883 records: 680 for 1850, 1,723 for 1880, and 3,480 for 1910 – an increase in line with the figures in the published statistics.Footnote 4 This database provides the empirical basis for the discussion below. We will first discuss the main evolutions in migrants’ origins, before relating these to their profiles in terms of gender and occupation between 1850 and 1910. Next to the impressive expansion and broadening of Antwerp’s migration field, we will argue that the main evolutions observed here represent an overall loosening of the ancien régime link between migration distance on the one hand, and social selectivity on the other hand. This resulted in an overall democratization of long-distance migration, in the sense that more people with lesser means tended to move over larger distances. By focusing on gender and social class as markers of social selectivity and by examining the stepwise nature of the moves of these growing numbers of long-distance migrants, we gain more insights into the new trajectories of these “modest” migrant groups.

Nets cast wider: an expanding and broadening migration field

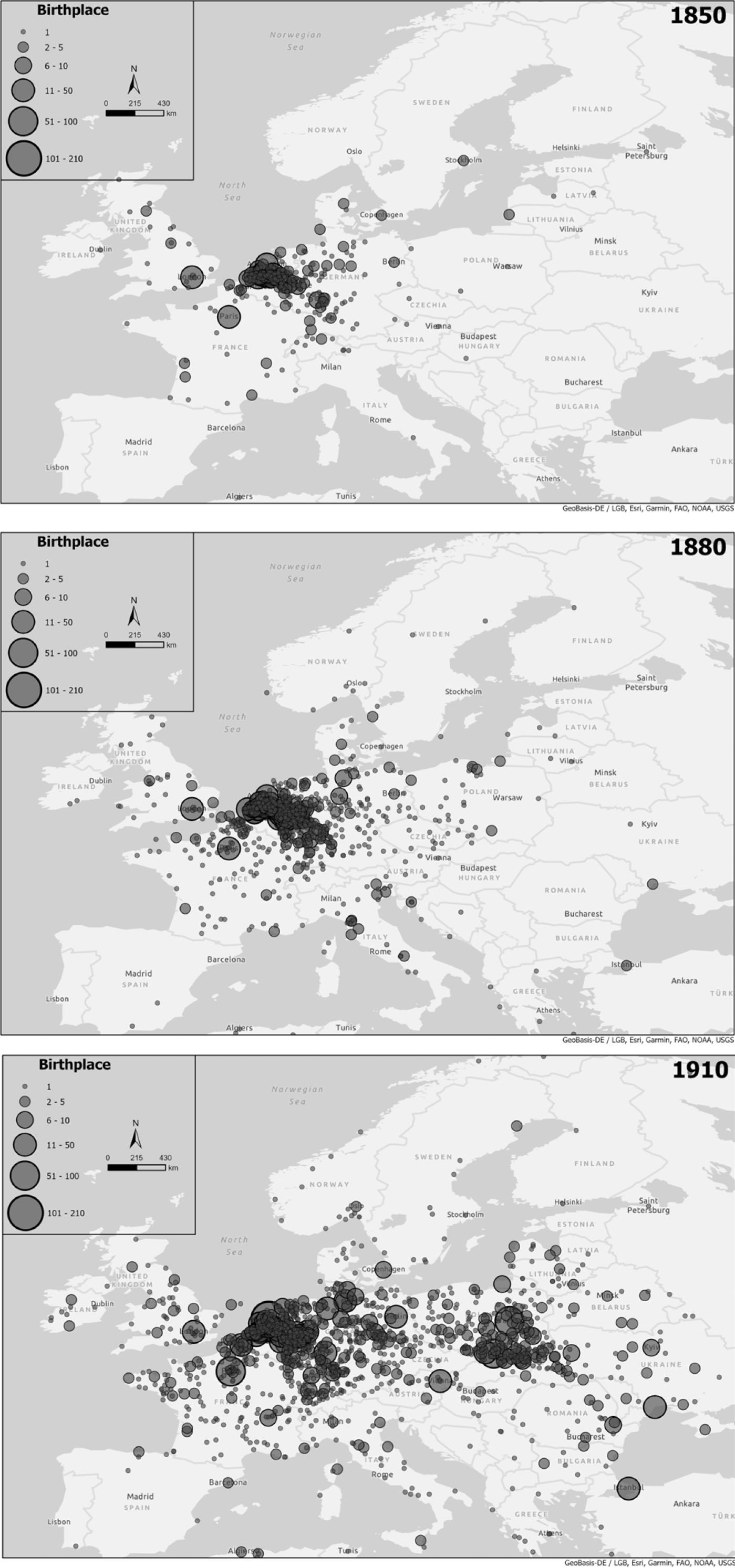

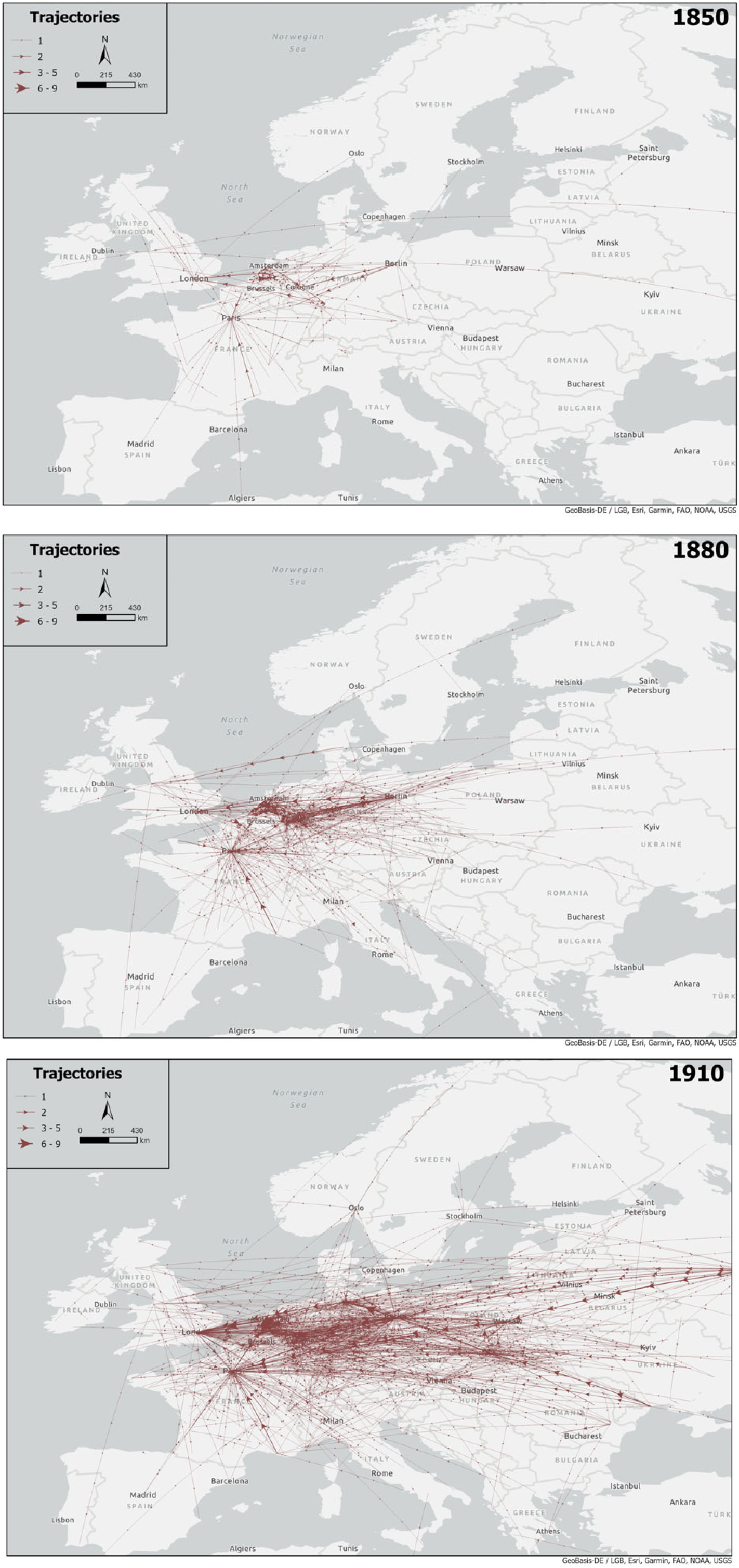

While the overall number of foreign newcomers to Antwerp grew considerably between 1850 and 1910, so did the area where they hailed from. Comparing Maps 1.1–1.3 illustrates an impressive expansion of the city’s migration field, in which there was a decreasing relative importance of nearby border regions and an increasing importance of more distant regions of origin, especially from the north-east.Footnote 5 With Antwerp located only 20 km south of the Dutch border, “international” migration from the Dutch border regions had been part of Antwerp’s regional migration field for centuries. We know for instance from earlier research that these regions supplied more than two-thirds (68%) of foreign residents in the 1796 census, when Antwerp was merely a regional textile center (Winter Reference Winter2009). Whereas Dutch border regions in 1850 still supplied 41% of all foreign newcomers, by 1880 this was only 28%, and in 1910 barely 12%.Footnote 6 In 1880 they were complemented mainly by growing numbers from the German border regions (24%),Footnote 7 with which intense commercial interaction was invigorated by Antwerp’s revived port activity and an early railway connection (the “Iron Rhine,” in 1843) (Devos and Greefs Reference Devos and Greefs2000; Vrints Reference Vrints2002). By 1910, Antwerp’s migration field clearly surpassed not only the cross-border regions but also the neighboring countries. Most conspicuously, by 1910 Central and Eastern Europe were supplying 27% of newcomers, whereas this had been 4% at most mid-century.

Map 1.1–1.3. Place of birth of foreign newcomers to Antwerp, 1850–1910 (N).

Source: DFFA, 1850–1910.

Since these spatial shifts took place in a context of rising overall numbers, they correspond to a continuity of cross-border streams in absolute terms, primarily of Dutch and increasingly also German origin, supplemented by a surge in the number of people from more distant European origins, such as from present-day Poland (from three in 1850 to 506 in 1910), Ukraine (from zero to 105) and Russia (from two to 51). Map 1.3 shows that most of this Eastern recruitment was concentrated in what was then the Kingdom of Galicia under Austrian rule, and adjacent Polish areas under Russian and Prussian rule, a poor, predominantly rural, area with an increasingly persecuted Jewish minority, which was also heavily involved in transatlantic migration by the late nineteenth century (Steidl Reference Steidl2021: 133–36). Clearly, some of them were not merely passing through Antwerp on their way to the Americas (Caestecker and Feys Reference Caestecker and Feys2010), but settled in the city, their journey facilitated by the denser rail network that connected Eastern Europe to Belgium via Germany (Martí-Henneberg Reference Martí-Henneberg2021: 226). Although the foreigners’ files did not record religious denomination, many of these Eastern newcomers likely had a Jewish background. Hence, their immigration featured in the attested expansion of the Jewish population in Antwerp from an estimated 1,000 prior to 1880 to 20,000 on the eve of World War I, mainly from Eastern European origin (Saerens Reference Saerens2000: 6–9; Schreiber Reference Schreiber1996; Vanden Daelen Reference Vanden Daelen2018).

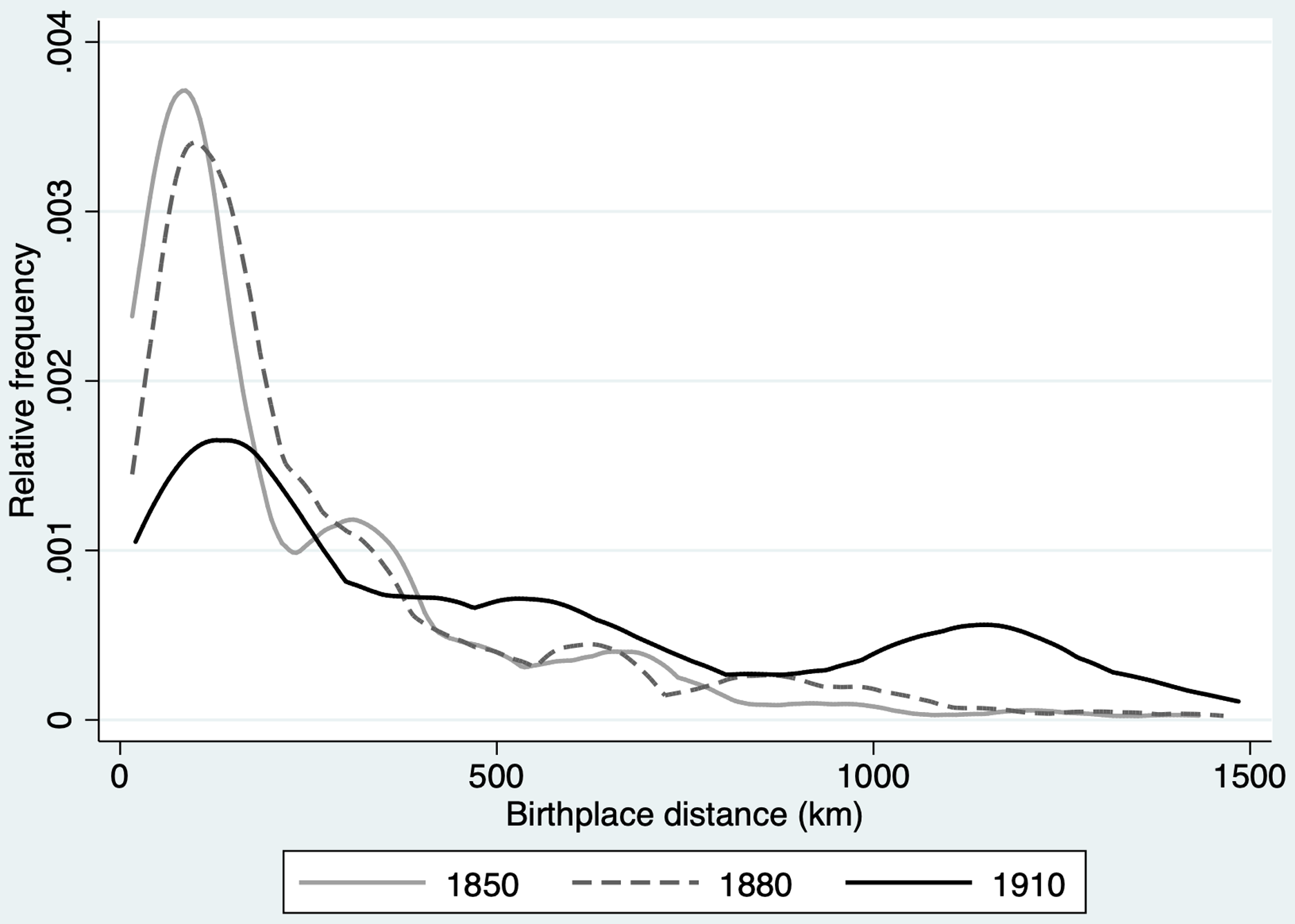

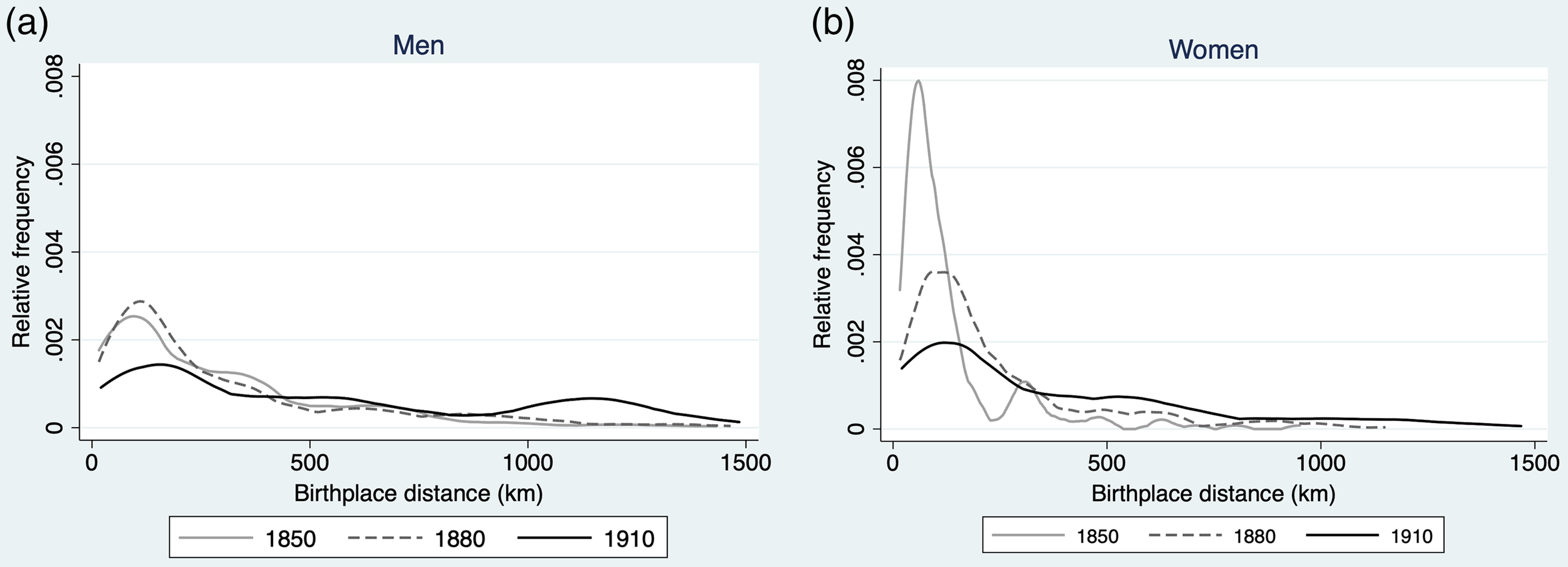

In quantitative terms, the marked expansion of Antwerp’s migration field implied a flattening of the distance-decay effect over time (Graph 2). In 1850 and somewhat less so in 1880, the lion’s share of foreign newcomers had traveled only a couple of hundred km at most. By 1910, however, the distance-frequency line had become much flatter, as a majority by then had traveled more than 600 km. Over this 60-year period, the mean birthplace distance more than doubled, from 275 km in 1850 to 351 km in 1880 and 695 km in 1910, while the median more than tripled from 133 km over 179 km to 450 km respectively. While a first shift towards longer distances was observable in 1880, the major shift took place in the run-up to 1910.

Graph 2. Birthplace distance distribution (km) of foreign newcomers to Antwerp, 1850–1910.

Source: DFFA, 1850–1910.

As Maps 1.1–1.3 demonstrate, the overall expansion of the foreign migration field went hand in hand with its broadening, in the sense that migrants originated from a wider array of places by 1910 than in 1850, increasing the number of different birthplaces from 357 to 1,837. This meant that most arrivals in 1910 (54%) were born in a place that did not figure among their 1850 or 1880 counterparts. Furthermore, 41% of arrivals in 1910 had a “unique” birthplace, i.e., one that supplied only one immigrant that year, which may indicate the limited importance of direct personal connections as a channel of (chain) migration.Footnote 8 Conversely, the proportion of newcomers born in the ten most frequent places of birth decreased from 21% in 1850 to 17% in 1910, another indication of the “broadening” of migration. The composition of these top 10 birthplaces also changed considerably over time, reflecting the city’s expanding migration field. In 1850 the top 10 consisted primarily of regional centers in the Dutch border provinces such as Breda, Bergen op Zoom, Tilburg, and ‘s Hertogenbosch, with only Amsterdam (#1), London (#3), and Paris (#7) as major cities, yet relatively nearby ones. In 1880, the image was already more exotic, with Paris, Cologne, Aachen, Rotterdam, and Amsterdam heading the list. By 1910, these were complemented by major eastern cities such as Krakow (#2), Warschau (#4), Hamburg (#6), and Berlin (#7). As growing numbers of newcomers came from an increasingly varied array of birthplaces, then, Antwerp was at the same time expanding its attraction in an eastern direction and connecting more firmly to an interurban European network.

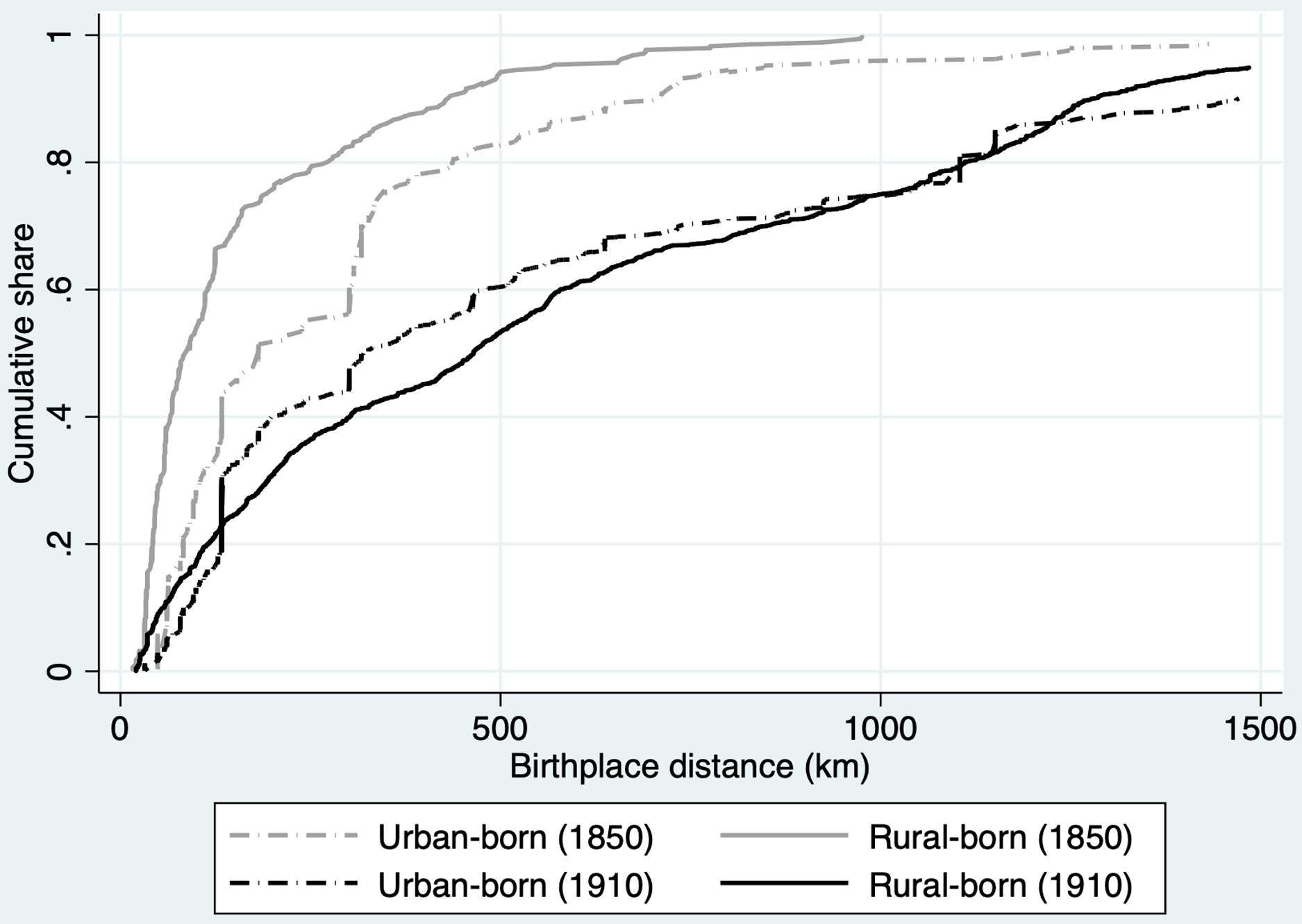

Urban places of birth, defined as places with more than 10,000 inhabitants, indeed became more important over time, providing 46% of all foreign newcomers in 1850 and 55% in 1910.Footnote 9 As this difference was attributable mostly to the “urbanization” of birthplaces over time, the increasingly urban background of Antwerp’s newcomers reflected Europe’s overall urbanization process in this period more than any urban-oriented shift in the city’s migration field.Footnote 10 Yet what did change markedly over time, was the relationship between birthplace size and distance. In 1850 urban-born migrants had traveled considerably longer distances than their rural-born counterparts, with a median of 181 km and an average of 362 km, against 86 km and 166 km respectively – a characteristic typical for preindustrial urban migration. This correlation, however, weakened and eventually disappeared over the next half-century (Graph 3). By 1910, rural-born newcomers recorded even higher median (469 km) and mean (652 km) birthplace distances than urban-born (317 km and 641 km respectively). On the eve of World War I, in other words, rural-born foreign newcomers had traveled as far as urban-born ones, and in this, they differed considerably from their ancien régime counterparts.

Graph 3. Cumulative birthplace-distance distribution of urban-born and rural-born foreign newcomers to Antwerp, 1850–1910.

Source: DFFA, 1850–1910.

The second half of the nineteenth century thus witnessed a clear expansion and broadening of the migration field of the port city, particularly in an eastern direction. Although migrants arrived from France and several Mediterranean countries as well as from Britain, most foreign newcomers came from the Netherlands and Germany, in addition to an increasing number from Eastern Europe, particularly from present-day Poland. The expansion and growing density of the European railway network provided the infrastructure to facilitate moving, while proletarianization and changing opportunities at home provided incentives to do so.

Trajectories and gateways

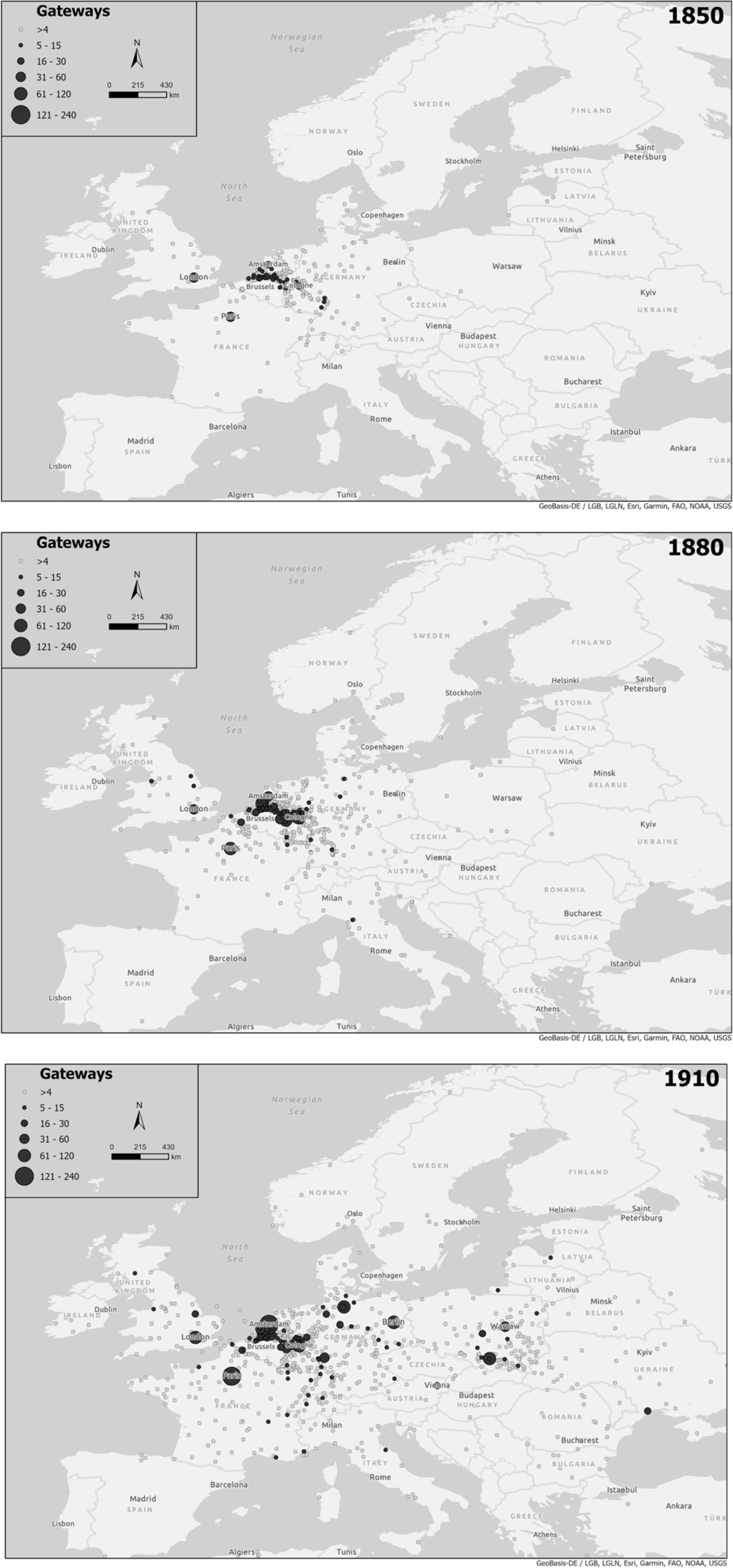

As birthplaces became more distant and more varied, newcomers were also considerably more likely to have traveled elsewhere before coming to Antwerp. While the foreigners’ files unfortunately do not inform us of the means of travel, comparing the last place of residence with that of birth does allow us to infer prior trajectories. As people may in reality have made multiple moves, the resulting figures provide a minimal proxy of prior mobility. In 1850, one in two (50%) foreigners had come to Antwerp directly from their place of birth, by 1880 (35%) and 1910 (34%) this was only one in three. Maps 2.1–2.3 illustrate how these diversifying trajectories of prior mobility added up to a widening and denser web of spatial connections throughout Europe (and beyond).Footnote 11 Not only were newcomers increasingly likely to have moved before coming to Antwerp but the distance of these prior trajectories also increased.Footnote 12 Not always did their trajectories bring them closer: about one in three (35%) indirect migrants had a last place of residence abroad that was actually located further from Antwerp than their place of birth. The resulting expansion in cumulative migration distance – i.e., the sum of distance between birthplace and last place of residence, and between the latter and Antwerp – was impressive: from a median of 144 km in 1850 to 571 km in 1910, and an average of 418 km to 971 km.

Map 2.1–2.3. Prior trajectories of indirect foreign migrants to Antwerp, 1850–1910 (N).

Source: DFFA, 1850–1910.

Note: Arrows indicate moves from place of birth to last place of residence abroad before arriving in Antwerp.

Unsurprisingly, newcomers from more distant regions displayed higher rates of indirect migration than those from more nearby regions: the longer the distance covered, the higher the chance of intermediate stops on the way. However, this correlation between birthplace distance and indirect migration was not as rigid as might be expected and became muddled over time. Although the Dutch still provided the highest share (44%) of direct migrants in 1910, also one in three (34%) among the relatively “new” distant groups from Eastern and Central Europe traveled to Antwerp directly, which was considerably more than the Germans (27%) and French (25%). This might be explained not only by the expansion and growing density of railway networks across the European continent and by economic opportunities, but also by more pronounced push factors in the region of origin and the importance of chain migration (Caestecker and Feys Reference Caestecker and Feys2010; Steidl Reference Steidl2021).

Urban-born migrants were more likely to have traveled directly (57% in 1850 and 44% in 1910) than rural-born migrants (48% and 25% respectively). This points to a pattern of stepwise migration, where rural-born migrants first moved to nearby cities before traveling on, to Antwerp and elsewhere. Adding the available information on the size of last places of residence to that of birth, raises the proportion of newcomers from an urban background from 46% to 60% in 1850, and from 55% to no less than 80% in 1910. In other words, most foreigners arriving in Antwerp, although often born in the countryside, had lived in other cities before coming to Antwerp, increasingly so as the second half of the long nineteenth century progressed. Over this period, Antwerp became more firmly included in both stepwise and interurban migration trajectories over longer distances.

Some cities were particularly important as “gateways” channeling migrants to Antwerp and here too we observe important changes over time (Maps 3.1–3.3). One is diversification, in the sense that indirect migrants came from a more varied array of last places of residence as the century progressed: 50% of all indirect migrants came from only 15 gateways in 1850, yet 24 gateways in 1880 and 33 gateways in 1910. Over the same period, the average distance of these gateways to Antwerp increased from 172 km over 201 km to 478 km. Apart from the continued importance of Paris and London, there was a clear trend towards internationalization, whereby nearby towns in border regions were overtaken by more distant cities of international standing. The number of Dutch cities in the top 20 gateways decreased from 12 in 1850 over 9 in 1880 to only 4 in 1910 – retaining the major cities of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and The Hague – while the number of cities in present-day Germany increased from 4 in 1850 to 7 in 1880 and 8 in 1910, adding major eastern cities such as Berlin and Hamburg to nearby towns such as Cologne, Düsseldorf, and Aachen. Also featuring cities such as Krakow, Warschau, New York, and Vienna by 1910, the changing composition of the gateway top 20 reflected Antwerp’s expanding and increasingly international migration field, and more generally a situation of overall widening transport infrastructure and intensifying mobility throughout Europe.

Map 3.1–3.3. Last place of residence abroad of foreign newcomers to Antwerp, 1850–1910 (N).

Source: DFFA, 1850–1910.

Note: Visualization includes last residence abroad for both direct and indirect migrants, i.e., both those whose place of birth was also that of last residence abroad and those where these two places differed.

Not all gateways had the same allure. Dutch cities primarily channeled Dutch migrants, just like nearby German towns such as Düsseldorf and Köln mainly sent German migrants, and Krakow and Warschau those born in present-day Poland, and to a lesser extent Ukraine. London, on the other hand, was a truly international gateway, channeling only a handful of British migrants, but many more from all over Europe, especially from Germany and Central and Eastern Europe. Cities such as Paris, Hamburg, and Berlin were somewhat in between, sending about as many compatriots as international migrants. In addition, 5% of Antwerp’s newcomers in 1910 had first resided in Brussels, Belgium’s capital city located at c. 45 km distance, which offered a nearby alternative destination (Goddeeris Reference Goddeeris2013). Although unfortunately the foreigners’ files do not inform us of newcomers’ subsequent mobility, there is no doubt that most of them moved on again (Greefs and Winter Reference Greefs, Winter, Blondé, Geens, Greefs, Ryckbosch, Soens and Stabel2020a), making their stay in Antwerp one stage in their increasingly wide and complex migration trajectories.

As migration trajectories became longer and included more rural-born migrants, then, indirect migration became more important, with several major cities both in the vicinity and further away playing important roles as gateways for Antwerp-bound migration. In the following paragraphs, we will demonstrate how this increase in migration distance went hand in hand with a loosening selectivity in terms of gender and occupation.

Gender and marital status: changing constellations

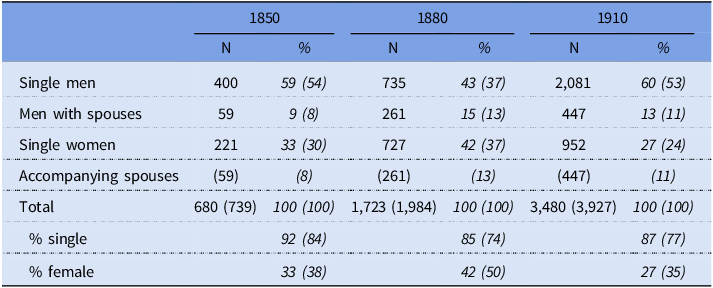

Foreigners’ files were compiled for heads of households, which means that women were recorded in their own right only if they were unmarried, widowed, or unaccompanied by their husband: married women were simply mentioned in their husband’s file if they arrived together and remain obscured from further analysis (see also Hoerder Reference Hoerder, Hoerder and Kaur2013: 24). Following the registration logic of the foreigners’ files, the dataset used here pertains to household heads and therefore underestimates not only women but also married couples among foreign newcomers. Nonetheless, they allow us to establish that most foreign newcomers were young and single. The median age of the household heads recorded in the foreigners’ files was 26 for men and 24 for women, without great change throughout the period, while singles comprised 92% of all files in 1850, 85% in 1880, and 87% in 1910 (Table 1). We can moreover induce the “obscured” number of female spouses from their husband’s file (bracketed figures in Table 1), which increases the share of migrants arriving as a married couple from 16% in 1850 to 23% in 1910. This increase was general, in the sense that it was not particular to specific geographical backgrounds. While these figures indicate a slight shift towards more family migration over time (increasing the female “omission bias” in the foreigners’ records), single adults remained predominant throughout as regards both men and women.

Table 1. Gender and marital status in Antwerp’s foreigners’ files, 1850–1880

Source: DFFA, 1850–1910.

Note: Non-bracketed figures refer to the number of foreigners’ files. Bracketed figures refer to the extrapolated total of adults in the files, i.e. including female spouses accompanying their husband on the basis of their being mentioned in their husband’s file (see text). Everyone arriving without an accompanying spouse is counted as single in this table. According to information on civil status, those arriving ‘single’ were primarily unmarried (88%), married but not accompanied by their spouse (8%) or widowed (4%). Accompanying children are not included in this table, nor are the very rare instances where non-married adults (e.g., siblings) were recorded together on one bulletin.

As discussed in the introduction, in ancien régime cities, women typically moved over shorter distances, while long-distance migration was primarily a male affair – a pattern that was also observed for Antwerp in the first half of the nineteenth century, when foreign-born men far outnumbered women (Winter Reference Winter2009). Yet in the second half of the nineteenth century, women started to participate in greater numbers in foreign migration – although the evolution was not linear. Female catch-up in foreign migration took place primarily between mid-century and the 1880s (Greefs and Winter Reference Greefs and Winter2016). Local annual statistics (available from 1863 onwards) show that women made up about 50% of Antwerp’s foreign immigrants in the 1860s to 1880s, but only c. 40% in the 1890s and 1900s (Gemeenteblad 1850–1915). Similarly, local census results show that the share of women among foreign residents increased steadily between the censuses of 1846 and 1890 (from 43% to 55%), but then declined again to 50% in 1910 (Statistique de la Belgique 1846–1910). Yet in general, as in other European areas, the presence of foreign migrants became more gender-balanced in Antwerp (Donato and Gabaccia Reference Donato and Gabaccia2015; Schrover Reference Schrover, Hoerder and Kaur2013).

Although the foreigners’ registers underestimate the female presence by recording only single women, our sample elucidates the dynamics underlying women’s changing role in foreign migration between 1850 and 1910. Women accounted for 33% of foreigners’ files in 1850 and 42% in 1880, but only 27% in 1910. When we correct for the omission of married women, the female share evolves from 38% in 1850, over 50% in 1880, back to 35% in 1910 (Table 1), corroborating a chronology of increasing female presence up to c. 1880, followed by a relative decrease in the following decades. Following the categorization of Gabaccia and Zanoni (Reference Gabaccia and Zanoni2012), the more balanced gender ratio (between 47 and 52% female migrants) in 1880 shifted again to a slightly male-predominant one (between 25 to 47% female migrants). In absolute terms, this reflected a two-speed increase in the number of female foreigners, being overtaken by a steadier increase among their male counterparts: between 1850 and 1880 the number of women increased by a factor of 3.5, but between 1880 and 1910 only by 1.4, while among their male counterparts, this was 2.2 and 2.5, respectively.

Geographically, the growing presence of female foreign migrants went hand in hand with a restructuring of gender patterns in Antwerp’s migration field. In 1850 female foreign migration was primarily a cross-border regional affair: 64% of women recorded in the foreigners’ registers came from the nearby Dutch border regions. By 1880 this share had dropped to 32%, to the benefit primarily of an increased influx from the German Rhineland (28%). By 1910, even combined, Dutch (21%) and German (13%) cross-border migrants supplied only a minority of foreign women, as more and more moved from more distant regions and countries. The increasing mileage of female migrants is illustrated in Graph 4, which shows how their migration-distance curve flattened quite spectacularly between 1850 and 1910. In 1850, only 16% of foreign women had traveled more than 200 km, by 1880 this was 37%, and by 1910 55%. Their median birthplace distance tripled from 83 km via 153 km to 249 km over the same period, while the average increased even more from 131 km via 259 km to 454 km.

Graph 4. Birthplace distance distribution of male and female foreign newcomers to Antwerp, 1850–1910.

Source: DFFA, 1850–1910.

Compared to their male counterparts, dynamics of both convergence and divergence were at play. Convergence took place when we restricted our view of birthplace distances to less than 1,000 km, which made up the bulk of foreign migration. In this segment, women caught up with men over time, resulting in converging curves and measures of distribution.Footnote 13 Yet at the same time, they diverged with regard to very-long-distance migration, especially after 1880: the proportion of men traveling more than 1,000 km increased from 4% in 1850 over 7% in 1880 to 32% in 1910, while women lagged behind at 0%, 2%, and 11%, respectively. This was attributable primarily to marked gender biases for the distant regions that came to the fore after 1880. In 1910, the proportion of (single) women among foreigners from border countries was between 30–40% but fell below 15% for those from Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe and other continents. It is worth recalling that female data are limited to single women only: including married women would likely narrow the observed gender gap in migration distance, but not efface it.Footnote 14 Taken together, dynamics of gender convergence dominated between 1850 and 1880 and were followed by dynamics of divergence in the period up to 1910, which were situated primarily in the tail of the distance distribution. While the latter complicates the picture, the end balance does add up to an overall weakening of gender selectivity in migration distance over time, with the (important) exception of the new, male-dominated segment of very long-distance migration.

Occupation and social class

Long-distance migration to early modern cities was typically not only a male but also an upmarket affair, in which highly skilled, specialized, and/or wealthy migrants were overrepresented compared to regional counterparts – and such continued to be the case in Antwerp in the first half of the nineteenth century (Winter Reference Winter2009). By the second half of the century, however, the – qualified – process of feminization went hand in hand with one of democratization, as differences between men and women were also intertwined with social distinctions. To establish migrants’ social positions, we used HISCO and HISCLASS to convert male and female occupations to social class (Van Leeuwen and Maas Reference Leeuwen and Ineke2011; Van Leeuwen et al. Reference Leeuwen, Maas and Miles2002).Footnote 15 Overall, foreign migrants maintained relatively high-class positions in the period 1850–1910, as far as can be gauged from their occupational denomination. Although the share of elite members decreased from 8% in 1850 to 4% in 1910, that of middle-class and skilled workers increased from 23% and 7% to 31% and 17%, respectively. Conversely, the share of low-skilled workers remained constant at 17%, while that of unskilled workers decreased from 45% in 1850 to 31% in 1910.

The overall advance of foreigners’ social class was the result of both changes in societal stratification overall and of an increasingly diverse opportunity structure of Antwerp’s port economy. Next to diversifying its functions as commercial transport hub and service center, industrial activities connected to intercontinental port traffic, such as sugar refineries, rice mills, shipbuilding, metalwork, and diamond industry, also expanded considerably over the period in question (Loyen Reference Loyen and voor Antwerpse Geschiedenis2008; Veraghtert Reference Veraghtert and Suykens1986). This is reflected in the diversification of the occupational profile of Antwerp’s foreign newcomers over time. Among foreign women, the share of domestic servants declined from 72% in 1850 over 55% in 1880 to 47% in 1910, attesting to widening of employment opportunities for (single) women in the city’s commercial, retail, and leisure sectors, as shop girls, waitresses, or sex workers but also, at the end of the period, more upmarket positions as cashiers, teachers, and clerks.Footnote 16 Antwerp’s booming port economy also multiplied and diversified employment opportunities for male profiles, from merchants, clerks, and commercial agents, via actors, waiters, and singers to toolmakers, building workers, shipwrights, and, by the end of the period, electrical engineers, and diamond workers. In addition, by 1910, 4% of men came to Antwerp to study, while 11% of women were members of religious congregations.

Occupational orientation differed according to geographical background. Dutch cross-border migrants were, for instance, oriented more toward domestic service and casual labor, while French workers were overrepresented in the hospitality industries, Germans in white-collar commercial activities, Scandinavians in shipping, and Eastern Europeans in diamond processing. Such geographical clustering was however never dominant, as these “niche workers” were accompanied by compatriots in other sectors, while, conversely, all occupational activities drew newcomers from various regions. Overall, the extent of geographical clustering in occupational activities declined over time, except for those relatively “new” groups in 1910, as Eastern Europeans dominated the inflow of foreign diamond workers and traders that accompanied the spectacular take-off of the Antwerp diamond industry in the late nineteenth century, overtaking Amsterdam and employing many Jewish workers (Hofmeester Reference Hofmeester2013).

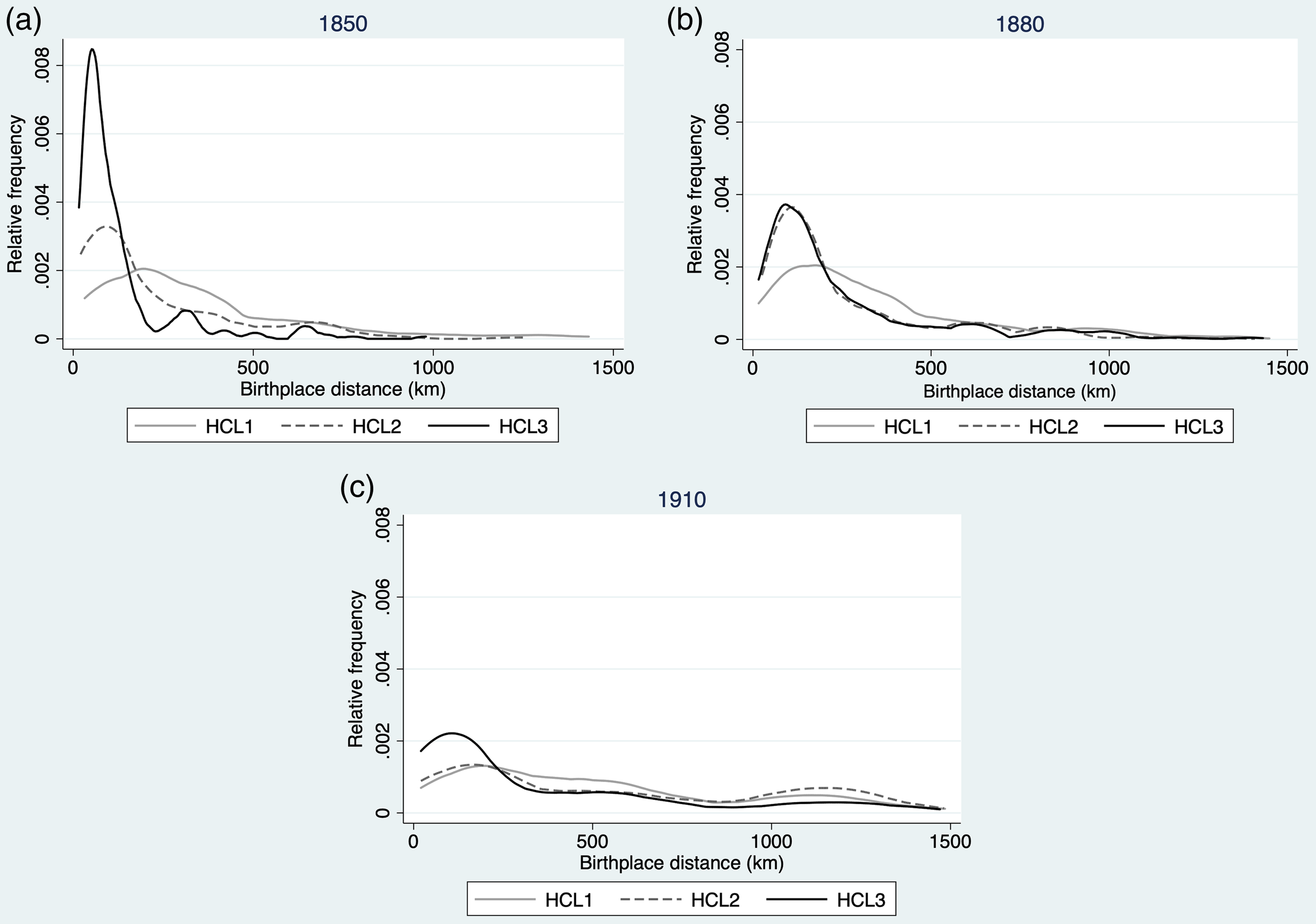

The “upgrading” of foreigners’ social class over time, interestingly, was not a reflection of their increasing migration distance. On the contrary, as their occupational profiles diversified, the correlation between migration distance and social class weakened over time. Graph 5 illustrates how the flattening of the birthplace-distance curve went hand in hand with its convergence between status groups. In 1850 social selectivity in migration distance was still marked: the median birthplace distance of elite & middle-class migrants was more than double that of skilled workers, and four times that of unskilled workers. Over time, this gap decreased considerably: between 1850 and 1880 unskilled workers caught up with skilled workers, and in 1910 the latter approximated elite & middle-class migrants in terms of birthplace-distance distribution. While the average birthplace distance of elite & middle-class migrants had less than doubled from 422 km to 743 km between 1850 and 1910, that of their unskilled counterparts had increased more than fourfold from 127 km to 537 km. On the eve of World War I, even low-skilled foreigners traveled long distances, and in this, they were at the vanguard of new migration dynamics ushered in by the transition from preindustrial to industrial society.

Graph 5. Birthplace distance distribution of foreign newcomers to Antwerp according to social class, 1850–1910.

Source: DFFA, 1850–1910.

Note: HCL1: Elite & middle class = hisclass 1–5, HCL2: Skilled manual workers = hisclass 6–10, HCL3: Unskilled manual workers = hisclass 11–12.

Conclusions

In this case study, we have analyzed the social backgrounds and trajectories of c. 5,000 foreign immigrants to Antwerp between 1850 and 1910 to demonstrate a process of decreasing social selectivity of migration distance. As immigration to the Atlantic port city expanded both in size and in scope, the distance-decay effect characteristic of foreign immigration in earlier periods gave way to a flattening of the birthplace-distance curve over time and a marked elongation of its tail, especially in the period 1880–1910. As migration distances increased, trajectories became more complex. The growing diversification and internationalization of gateways channeling Antwerp-bound migration reflected a context of widening migration horizons throughout Europe and beyond. During this process, the correlation between birthplace size and distance disappeared, while that of social class and gender weakened. The result was the appearance of large numbers of non-elite migrants who traveled long distances, a process which we proposed to call the “democratization of long-distance migration,” which we believe was the most important novelty of Europe’s “mobility transition.” After Lucassen and Lucassen’s (Reference Lucassen and Lucassen2009) influential re-evaluation of Europe’s migration levels in the long nineteenth century, and subsequent quantifications of the changing gender dimensions (Donato and Gabaccia Reference Donato and Gabaccia2015; Gabaccia and Zanoni Reference Gabaccia and Zanoni2012; Schrover Reference Schrover, Hoerder and Kaur2013), this article’s identification of the process of decreasing social selectivity of distance, constitutes a crucial contribution to our understanding of migratory change during this period of societal transformation.

To be sure, the causes of this “democratization of long-distance migration” have been inferred, rather than studied directly in this study, let alone demonstrated. Only follow-up research can lay bare the actual importance of railway expansion, improving transport by road and sea, decreasing travel costs, increasing literacy, labor market formalization, chain migration, and other factors for the different migrant groups involved. Yet rather than to explain the process of decreasing migration selectivity, the prime endeavor of this study was to demonstrate its existence and highlight its proportions. Another caveat is that the observed evolutions were partly painted by the specificities of Antwerp’s history and registration practices. Its increasing attraction over time was, for example, (also) attributable to the city’s promotion from mid-sized regional port to prime transatlantic hub. Yet many cities were undergoing similar dynamics of unprecedented expansion and economic transformation in this era, and in that sense, Antwerp’s specific experience was but one variation on a Europe-wide process of urbanization. Crucially, its new groups of long-distance migrants represented more than simply a rise up the urban ladder, as the underlying declining social selectivity of migration distance was characteristic of a radically new dimension of migratory change. Although it has at times been implied in other research on this period, we know of no other studies that have explicitly argued nor quantified this trend of democratization of long-distance migration over time.

We believe that placing the focus on the weakening social selectivity of migration distance in the second half of the long nineteenth century is crucial to put the “mobility transition” in perspective. What was radically new in this period was not so much the arrival of large numbers of migrants, nor even of relatively exotic migrants, but the arrival of large numbers of long-distance migrants who were not necessarily male, high-skilled, or urban-born. These shifts, we believe, did not merely represent abstract quantitative measures, but implied a fundamental restructuring of centuries-long characteristics of urban migration, which radically transformed the migration experience both of the migrants involved and of urban society.