Introduction

The population of countries around the world is ageing; many industrialised countries currently have life expectancy above eighty years old; and there are projections showing that by 2030 many high income countries will have female life expectancy close to ninety years old, if not above (Kontis et al., Reference Kontis, Bennett, Mathers, Li, Foreman and Ezzati2017). As a result, more emphasis is put on the importance of delivering a satisfactory social care system able to deal with the needs of the older population. An essential part of the system is its funding. This article focuses on funding and main aspects of delivery of long-term care (LTC), also known as social care or social assistance for older people. This research is focused on a range of developed countries, of similar income per capita and other demographic characteristics and sharing a concern for the wellbeing of elders as a social issue: namely, Austria, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, Netherlands and the four countries of the United Kingdom (England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland). As a side note, at the time of writing, the world is experiencing a pandemic caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) and the expected economic impact of the pandemic is likely to be significant (International Monetary Fund, 2020). However, the purpose of this article is to mainly describe different funding systems and the characteristics of several countries prior to the pandemic in order to provide a range of perspectives for researchers and policy makers. The aim of the article is to provide a broad perspective of funding arrangements and, in doing so, provide references to work that discuss specific aspects in more details.

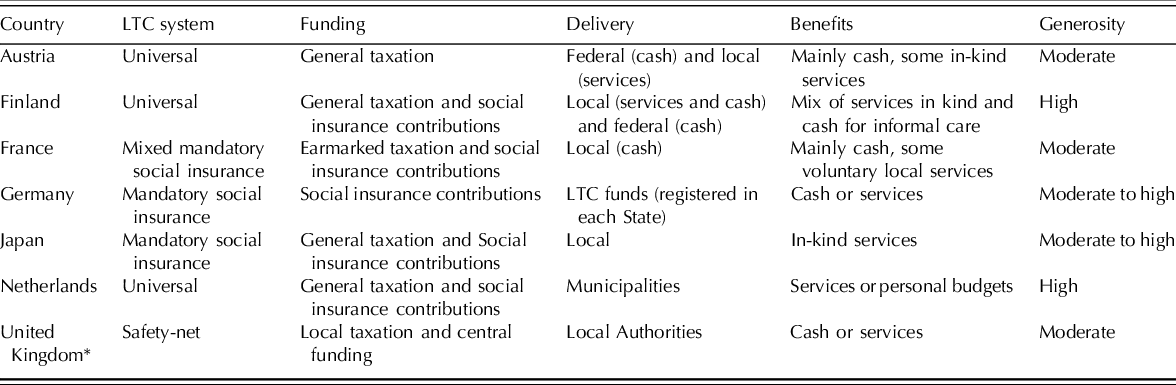

By collating and discussing the main features of several social care funding and delivery systems, this research aims to help planning the way forward, adapting the funding and delivery of social care as a response to the current global health crisis, demographic changes and fiscal adjustments. Table 1 summarises LTC funding, delivery and generosity of benefits. Some countries, such as in the United Kingdom (UK), follow a ‘safety-net’ model in general, where the benefits are means-tested and are only available to the poor or to individuals who have exhausted their savings paying for services in care homes – however, threshold limits are less strict for home care services and in Scotland there is free personal care for any adult in need of home care services. Others have a co-operative model, such as Germany, where long-term care insurance (LTCI) is simply another pillar of the social welfare system similar to healthcare, with a few restrictions. There is also the “Scandinavian system” where access to benefits is universal to all its citizens, such as in Finland.

Table 1 Summary of LTC characteristics

The generosity of benefits is somewhat linked with each country’s overall stance on other welfare issues, i.e. the more generous overall, the more generous is the support for LTC. However, there are exceptions to the norm such as in England where the National Health System (NHS), for example, universally provides healthcare, but support for LTC is budget constrained and means-tested.

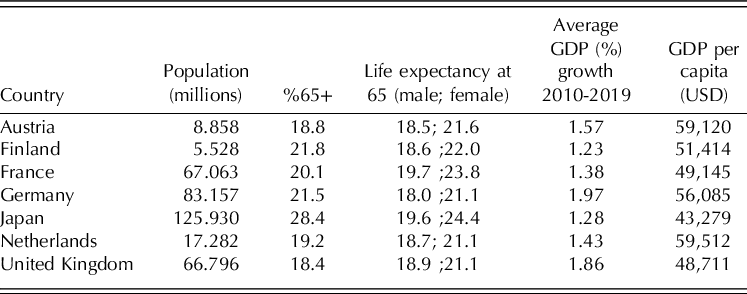

Table 2 summarises some key characteristics from the countries discussed. They differ in population size, demographic composition, economic aspects and funding methods for long-term care. Japan, for example, has the highest percentage of older people (sixty-five years or older), partly due to their long history of investments in health care for older population that goes back to 1874 (Olivares-Tirado and Tamiya, Reference Olivares-Tirado and Tamiya2014). Overall, countries do share some traits such as similar proportion of older population, life expectancy, average GDP growth and a well-developed LTC system.

Table 2 Selected characteristics from nine developed countries

Source. OECD.stat; data for 2019 or closest year.

Funding arrangements

Funding for social care, or long-term care (LTC), can come from different sources and usually a combination of sources (Cylus et al., Reference Cylus, Roland, Nolte, Corbett, Jones, Forder and Sussex2018). They range from mandatory social insurance, or long-term care insurance in Germany and Japan, to fully tax funded in Austria, or a mix of both in the case of France and Netherlands. Some countries are more generous than others, funding a larger part of LTC costs, but no country fully funds the cost of LTC in our sample of countries, which means co-payments are often expected. The three main sources of funding are taxation, long-term care insurance and out-of-pocket payments or private arrangementsFootnote 1 . The remainder of this section will outline the different types of funding systems.

Taxation

Taxation can be collected from individuals or companies, in a direct manner such as income tax, or indirect such as value added tax, and it can be pooled into a general pot or be earmarked (ring-fenced or hypothecated) for a specific purpose. It can also be charged at a national or sub-national level. Each dimension can shape how equal, progressive and sustainable the funding system is. Taxes collected at a national level can be distributed locally, levelling out differences in local taxation revenue, ultimately improving equality at a national level. For example, Finland’s national government supplements local funding with grants (Kröger, Reference Kröger, Jing, Kuhnle, Pan and Chen2019) that form up to a third of public funding for LTC (Klavus and Meriläinen-Porras, Reference Klavus and Meriläinen-Porras2011; Anttonen and Karsio, Reference Anttonen and Karsio2016) as a response to inequalities in the quality of care across municipalities in the country (Kröger, Reference Kröger, Jing, Kuhnle, Pan and Chen2019). Austria also chose to supplement funding with state grants as a way to compensate loss of resources since a reform in December 2017 disregarded persons’ assets during means-assessments performed by municipalities (Fink and Valkova, Reference Fink and Valkova2018). Taxation is also the main funding option in Austria, where its main benefit, the Pflegegeld, is entirely funded by taxation collected nationally since 2012, when funding and organisation became centralised in the hands of the federal government (Miklautz and Habersberger, Reference Miklautz and Habersberger2014). Before this, the central government shared the funding responsibility with the nine regions of Austria, each of them with their own cash benefits (Landespflegegeld). Also in Austria, a combination of national taxation, taxation by the federal provinces and the municipalities funds LTC services in kind. Combined taxation is also used in Japan, alongside premium contributions. In general, 25 per cent of publicly funded LTC is funded by taxes collected by the central government, 12.5 per cent from the local prefectures and 12.5 per cent from municipalities. Similarly, in the Netherlands, a recent reform in 2015 decentralised a part of funding and municipalities are now responsible for non-residential services in accordance with the Social Support Act (WMO) while local health insurers are responsible for community nursing services and ‘body-related’ personal care, as prescribed in the Health Insurance Act (Zvw). Institutional care, however, is still funded by the national public LTC insurance scheme, outlined in the Long-term Care Act (WLZ) (Maarse and Jeurissen, Reference Maarse and Jeurissen2016; Alders and Schut, Reference Alders and Schut2019). The financial charges outlined in the Social Support Act varied from one municipality to another but since 2019 they were fixed nationwide. In 2020, the contribution could not exceed nineteen euros a month, up from 17.5 euros the year before. The contribution is not income dependent but low earners might be exempt from contributions (CAK, 2020).

Funding shortages might also occur when taxes are earmarked for LTC. What happens if the funding is not sufficient due to demographic ageing increasing demand for services or because of lower than expected tax revenue? France uses earmarked taxation to fund part of social care, with money from three different taxes hypothecated towards social care. The most recent tax, the contribution additionnelle de solidarité pour l’autonomie created in 2013, was implemented as a response to the insufficient amount of funds raised, improving the system’s sustainability. The French cash allowance, the allocation personnalisée d’autonomie (APA) receives 70 per cent of its funding from taxes collected by the local authorities (département), which are also responsible for the provision of the benefit (Le Bihan, Reference Le Bihan2018).

Local taxation is the main funding option in Finland, where municipalities are responsible for a large share, up to two thirds, of funding for LTC. Non-earmarked taxes are collected locally and local authorities decide how to allocate resources to meet several needs, including LTC (Johansson, Reference Johansson2010). In the UK, local taxation is also the main option of funding. It varies slightly between England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, and given recent budget cuts local taxation has increased its importance. England has seen the greatest cut, increasingly moving away from redistributive central government grants and towards local business and residential property taxes (Glendinning, Reference Glendinning2018).Footnote 2 More specifically, local taxation was put together in a national pot and redistributed as a revenue support grant, according to a formula, but since 2013 half the funds were retained at local level and used to fund expenditure (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2013). Plans were set to progressively let local authorities keep 75 per cent of taxes raised in 2022, but there was uncertainty on the benefits of this policy locally (Calkin, Reference Calkin2020). Now, the grant is distributed according to a set of complex formulae that take into account Local Authorities (LAs) taxation characteristics, with as little as zero percent of funds being distributed centrally (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, 2021). But in all four countries there is some degree of central funding, which comes from general taxation. In England, central funding comes mainly from the Better Care Fund (BCF),2 an initiative to promote integration between health and social care services, facilitating local support for people planning to manage their own health and wellbeing, living independently in the community for as long as possible (NHS England, 2020), which would reduce expenditure and pressure on the health system. Announced in 2013 and previously known as Integration Transformation Fund, the BCF did not bring new funds as it simply rearranged existing funds destined to health care or funds that were already being transferred from the National Health Services to social care (Bennet and Humphries, Reference Bennet and Humphries2014). In Scotland, funds are allocated to counties and LAs through the General Revenue Funding of Local Authorities, in Wales the Revenue Support Grant has this role, along with NHS Wales funding, and in Northern Ireland the integration between health and social care means the Department of Health (NI), through the five health and social care trusts, is directly responsible for funding and provision of long-term care (Oung et al., Reference Oung, Schlepper and Curry2020).

Long-term care insurance

Some countries opted for a pay-as-you go system in which premiums are paid towards a long-term care insurance where contributions are taken from payroll and the individual is entitled to care should the need arise in the future. The German LTC system was created in 1995 and went through changes but maintained its essence – universal coverage, funded by social insurance premiums, aimed at providing basic levels of care for people in need. The premiums have increased over the years going from 1 per cent in 1995 to 3.05 per cent in 2020, divided equally between employees and employers. Pensioners also contribute to the statutory social LTCI with the same rates, but since 2005 pension funds stopped paying half and now pensioners make up the difference, paying in full. Childless workers pay an extra 0.25 per cent since 2002 to reflect the likelihood of a greater reliance on public funds to pay for care later in life as opposed to support from family, and to reward parents for their time spent raising children (Curry et al., Reference Curry, Schlepper and Hemmings2019). Concerned about the impact that baby-boomers will have on demand for care in the future, Germany set aside 0.1 per cent of the contributions every year to form a fund that will not be used until 2035, when pressure on the LTC system is expected to rise significantly (Federal Ministry of Health, 2020b).

Another example of significant use of LTCI comes from Japan, having implemented their current system (Kaigo Hoken) in 2000. Half of Japan’s public LTC funding comes from taxation, but the other half comes from LTCI premiums. The municipal government starts collecting insurance premiums from workers age forty and above (Sakamoto H. et al., Reference Sakamoto, Rahman, Nomura, Okamoto, Koike, Yasunaga, Kawakami, Hashimoto, Kondo, Abe, Palmer and Ghaznavi2018). There are two types of insured groups and the premiums differ between them. Workers age forty to sixty-four years, called secondary group, have their premiums collected nationally which are later distributed to municipalities based on demographic characteristics. Pensioners aged sixty-five and older, called the primary group, have the premiums discounted from their pensions by the municipalities. The LTCI premium is typically paid as a supplement of around 1 per cent on health care insurance based on the employee’s choice of health insurer (Centre for Policy on Ageing, 2016). As many elements of LTC were previously the responsibility of the health insurance system in Japan, the current LTC insurance benefits are more generous than most countries (Ikegami, Reference Ikegami2019).

Other countries have small parts of LTC covered by mandatory social health care insurance contributions. Many elements of LTC in France are mixed with healthcare, which is why a large portion of the budget from the Caisse Nationale de Solidarité pour l’Autonomie (CNSA), responsible for funding part of LTC, comes from the employers and employees’ social insurance contributions for illnesses, with the yearly amount destined to LTC defined by the Objectif National des Dépenses d’Assurance Maladie (ONDAM). In 2021, the forecast budget for CSNA is 31.6 billion euros (CNSA, 2020a), but the CNSA is also funded by taxes and suppression of a bank holiday (Le Bihan, Reference Le Bihan2018). A consolidated breakdown of public expenditure from 2018 on funding of all health and social care elements of LTC, a total of 24 billion euros, showed that the CNSA contributed with 53 per cent of the public funds. The local authorities (départements) contributed with 19 per cent and the remaining difference was covered by health social insurance and central government contributions (CNSA, 2020b). Due to a recent change in the financing law, the CNSA will receive 1.93 per cent of a social tax on income, the Contribution Sociale Généralisée (CSG) (CNSA, 2021) and given changes based on a recent report, the cash allowance APA now can be based on the fees of institutional care, subject to means assessment (Le Bihan and Sopadzhiyan, Reference Le Bihan and Sopadzhiyan2019; French Public Service, 2021). Finland provides a care allowance for pensioners (eläkeläisten hoitotuki) that is organised by the Social Insurance Institution (KELA). It is funded by a mandatory social insurance contribution, taken from payroll, that mainly funds the health care system. In the Netherlands, the contributions outlined in the Long-term Care Act (Wlz) are similar to the current health insurance system and are based on premiums of the income tax up to a ceiling beyond which there is no charge. Currently, the payroll premium is based on 9.65 per cent of taxable income up to 34,712 euros (Zorgwijzer, 2020).

Mandatory LTCI can be collected by the government or private companies, but voluntary insurances are only collected by private companies. Approximately 10.6 per cent of the population in France is insured through voluntary private LTCI, but this is not a widely used option elsewhere – with the partial exception of Germany (as insurance there is mandatory). Close to 90 per cent of Germans are covered by statutory social LTCI, the remaining 10 per cent have private LTCI (Federal Ministry of Health, 2020a). Self-employed workers or civil servants are enrolled in the private system, and employees that earn more than 62,550 euros a year can choose between the social or private LTCI (Federal Government of Germany, 2020). The choice between social or private LTCI involves many elements, including individual autonomy and responsibility, efficiency, fairness, sustainability and risk pooling. Evaluating these elements, Barr (Reference Barr2010) used economic modelling and reached the conclusion that ex ante social insurance, that is mandatory social LTC insurance, would be the most efficient option, with the possibility for top-ups either through private savings or private LTCI. Such arrangements could be seen as a balance between efficiency, fairness and sustainability.

Out-of-pocket payments or private arrangements

Out-of-pocket payments, co-payments or private expenditure, are present in every country as public funding is insufficient to cover all the costs associated with LTC. Private contributions towards LTC are expected as there is either a limitation on how many public benefits are available, covering only the most basic aspects of LTC, or the care package provided explicitly demands a private contribution to cover the costs. Even in Finland, where the “Scandinavian system” provides generous benefits, private payments represent roughly 17 per cent of LTC funding (Klavus and Meriläinen-Porras, Reference Klavus and Meriläinen-Porras2011; Anttonen and Karsio, Reference Anttonen and Karsio2016). In Japan, standard co-payments of 10 per cent of LTC costs are required from users. A reform in 2014 enforced a higher contribution, of 20 per cent, from individuals with higher earnings from income or pensions. In 2018 a third category was created and currently about 3 per cent of users, earning more than 3.4 million yen a year [roughly 27,300 euros], must pay 30 per cent of costs. Another 9 per cent of users pay 20 per cent and the lowest earners continue paying 10 per cent. There is a monthly cap on co-payments of 44,400 yen [˜350 euros] for all users, after which the costs are entirely covered by public funds as long as the users are entitled to the benefits (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2017; Curry et al., Reference Curry, Castle-Clark and Hemmings2018).

It is common to have the LTC user pay for the services up to a limit, after which public funds cover the cost of care. Austrians who require LTC services in care homes need to pay up to 80 per cent of their income, including cash allowance and pensions, to cover the costs (Miklautz and Habersberger, Reference Miklautz and Habersberger2014) and after this limit the municipalities and provinces must cover the costs of care. However, due to different caps on private expenditure according to local legislation, home care has terms that are more generous overall and on average users pay about 25 per cent of the costs (Leichsenring, Reference Leichsenring2009).Footnote 3 France, alongside Austria, also has significant out-of-pocket spending in LTC. For home care services an average of 18 per cent of the cost of care is paid out-of-pocket but for room and board services in residential care this figure rises to 81 per cent (Doty et al., Reference Doty, Nadash and Racco2015). In the UK, exact details are outlined in individual national legislative acts in effect since the 2000’s and 2010’sFootnote 4 , but overall, after establishing need for care through a needs assessment, care users go through a means assessment to establish how much they need to pay for their care. In general, public funds work as a safety-net for the poorest part of the population or once personal resources have been exhausted, especially in England. There are some differences within the UK: Scottish adults are entitled to free personal care after passing a needs-assessment; there is a cap limit on weekly expenditure for home care in Wales, currently set at £80; and in Northern Ireland home care is free of charge for over seventy-five years old.

Private arrangements, where care is provided informally, are also common. In fact, almost 80 per cent of LTC in Europe is provided by family members (Hoffmann and Rodrigues, Reference Hoffmann and Rodrigues2010). Country estimates vary according to datasets and definition of informal care, but they range from 4 per cent in Germany (although this figure can be as high as 18 per cent) to 38.8 per cent in France.Footnote 5 The LTC cash allowance provided in Austria is often used to reward relatives that are providing informal care (there is no monitoring on how the individuals spend their cash allowance) as 80 per cent of people in need of care are attended in their homes by their relatives, most of whom are women (Riedel and Röhrling, Reference Riedel and Röhrling2016; Government of Austria, 2020). Finland also provides an allowance for informal care (omaishoidon tuki), but many times informal care is provided free of charge by friends and relatives. A large part of LTC in the UK is actually provided by informal care from family and friends. Actual estimates of the value of this informal care differ significantly. In 2011, it was estimated that informal carers provided services worth between £55 and £97 billion (Morse, Reference Morse2014). The Office for National Statistics suggested, in 2014, a figure of £56.9 billion (Office for National Statistics, 2016) and Carers UK, in 2015, published a report with estimates of £132 billion per year, a figure similar to its healthcare counterpart, the National Health Services (Yeandle and Buckner, Reference Yeandle and Buckner2015). The figures vary due to methodological choices, but they all show a substantial value. Elsewhere, the Netherlands has encouraged its citizens to seek informal care arrangements as individuals with lower needs would not have access to public funds and would have to organise home care themselves (Maarse and Jeurissen, Reference Maarse and Jeurissen2016; Alders and Schut, Reference Alders and Schut2019). A reliance on family, especially the older person’s children, is implied in Germany, given its extra 0.25 per cent charge on childless individuals. Furthermore, the choice to also offer cash benefits, alongside services in kind, was designed by the German government as a way to acknowledge the time invested by family caregivers (Da Roit and Le Bihan, Reference Da Roit and Le Bihan2007). In Japan, there is a strong sense of social responsibility originating from the Shogunate law, where the family is responsible for the care of its dependent members (Nakabayashi, Reference Nakabayashi2019). Due to this perception, coupled with the high degree of prevailing strong masculine social norms (Alders and Schut, Reference Alders and Schut2020), it was decided that cash allowances would not be available as feminist groups feared it could increase the pressure for women to provide care to family members, including in-laws (Ikegami, Reference Ikegami2007).

Delivery

Long-term care benefits can be provided in cash or in kind. Services in kind range from simple provision of meals at home, to assistance with activities of daily living (ADL) at home (home care) to all-inclusive care at nursing homes, including elements of health care. The delivery of LTC benefits plays an important role in the sustainability in the system: the more generous is the system, the greater the funding it requires.Footnote 6 As a consequence many countries have opted for increases in the threshold for eligibility to public benefits. Due to funding concerns, in 2015, Austria increased the number of hours of care necessary to qualify for its care cash allowance (Fink and Valkova, Reference Fink and Valkova2018). Currently, the lowest level of need according to its needs assessment, level one, requires between sixty-five and ninety-five hours of assistance with ADL per month according to federal regulation, for at least six months. The 2013-2015 reform in the Netherlands increased the level of need required for people to be admitted into a nursing home. The idea was that people should get more help at home and this would alleviate public expenses, but individuals with high need of care would still be eligible for public benefits. This shift towards arrangements at home reflects the new trend of ageing-in-place (at home), which is another attempt to cut costs of LTC while maintaining quality. The latest set of planned reforms (SOTE reform) in Finland was aimed at deinstitutionalising care, making ageing-in-place a priority; but it is not entirely clear if this change will cut costs (Anttonen and Karsio, Reference Anttonen and Karsio2016).

Centralisation or decentralisation of care is also seen as a pathway to saving costs, taking into account local and national characteristics. As mentioned earlier, the Netherlands opted for decentralisation of funding and provision of part of its LTC system. The extent to which the reform aimed at cutting costs is unclear, as evidenced by concerns from municipalities on the sustainability of the current fixed fee for LTC home care services (Kelders and de Vaan, Reference Kelders and de Vaan2018). Facing another situation, in Finland, the per capita expenditure in health and social care in 320 municipalities (some merged to provide care) ranges from 1,980 to 4,689 euros and the average expenditure is 2,940 euros, indicating the magnitude of the problems that municipalities face vary greatly (Kalliomaa-Puha and Kangas, Reference Kalliomaa-Puha and Kangas2018). Consequently, the SOTE reform was planned to reduce the number of authorities responsible for health and LTC, down to eighteen counties that would take charge of funding and organising provision of services. Scheduled to take place in 2020, the reform has been delayed due to political tensions which contributed to the fall of the government just five weeks before the 2019 planned elections (BBC, 2019). The reform was redrafted and was approved by parliament in late June 2021, transfering many aspects of health and LTC responsibilities from 293 municipalities to twenty-one regional authorities plus the city of Helsinki by 2023 (Yle, 2021).

Limiting access to benefits or the amount of benefits is another strategy implemented in several countries. In Germany there is an understanding that the benefits are not enough to cover full costs of care, but simply to ensure basic care. The needs-assessment done by the Medical Review Board (Medizinischer dienst der krankenversicherung) places the individuals’ care needs in a rank from one to five. The amount of benefits varies according to the type of benefit chosen (cash or in kind) and the level of care need, ranging from 125 to 2,005 euros (values for 2020). In Japan, benefits are available to people above sixty-five years old, part of the primary insured group. There are no benefits in cash in the Japanese systems and all users must choose from a selection of benefits in kind (Iwagami and Tamiya, Reference Iwagami and Tamiya2019). Benefits for the secondary group, age forty to sixty-four, is only available if the claimant presents a disability evaluated at the needs-assessment, determining how comprehensive the care package will be (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2016).

Conclusion

In this article we presented a brief description of funding models for long-term care in a sample of developed countries. The sample provides a wide picture of ways to fund and organise LTC showing how diverse these arrangements are. The only clear pattern that every country is facing is that of increasing costs due to the ageing population leading to increasing costs of LTC services, which are expected to continue to rise. Coupled with financial turmoil in the late 2000’s the increased pressure on the system has led to changes in many countries. Some opted for small incremental changes such as Germany, Japan and France where social insurance premiums were increased over time in Germany and Japan, and in the latter the creation of a new tax in 2013 alleviated the pressure on finances for the LTC system. Other countries opted for reforms, such as the Netherlands and Finland, seeking to increase efficiency and save resources.

The path for the reforms varied as some countries opted for centralised organisation while others chose the opposite. Austria, which uses cash benefits as the main form of support, decided in 2012 to centralise the benefit at the hands of the federal government, who is now responsible for provision of cash benefits. Finland also opted for centralisation as it is pushing a reform to bring together municipalities to form larger regions responsible for provision of LTC benefits. Going in the other direction, in 2015 the Netherlands has decentralised part of their LTC system, with municipalities taking up responsibility for LTC elements of home care. The UK has made no significant change to its decentralised system where local authorities are responsible for provision of LTC benefits, but since 2016/17 funding responsibilities have increased for English local authorities as they progressively rely on increases in local taxation to offset reductions in central government grants.

Reliance on informal care is another relevant aspect of LTC provision as countries actively encourage individuals to seek support within their family and friends network such as in the Netherlands. Cash allowances in Austria and Finland reward carers in an informal setting while Germany implies a reliance on family members as there is an extra premium of 0.25 per cent deducted from payroll for childless individuals. In Japan, due to cultural norms, cash allowances are not available as care provided by friends and family is seen as a civic duty with no need for monetary reward.

A move towards home care, or age-in-place, is widespread as countries recognise the potential for increased wellbeing of the older population and for savings to the public purse, as opposed to institutionalised care in care homes or nursing homes. This emphasis on home care is supported by ever-increasing eligibility criteria of needs-assessments, which leads people to seek their own arrangements or lower level of support at home until their needs for care are high enough to qualify for more benefits. Although both informal care and raising eligibility criteria have the potential to generate savings to LTC public funds, the evidence is inconclusive whether these are not offset by other factors.