Introduction

Restorative Approach (RA) is based on wider restorative theory which argues that repairing the harm caused by offences is best achieved by building better relationships between those involved rather than penalising the individual(s) who created the harm (Strang and Braithwaite, Reference Braithwaite, Strang and Braithwaite2000; McCluskey et al., Reference McCluskey, Lloyd, Kane, Riddell, Stead and Weedon2008; Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2009). RA shares the philosophical roots and methodology of Restorative Justice, a practice commonly employed in criminal justice systems, but differs in that it can be adopted to improve the everyday environments of diverse communities and organisations as well as being used to deal with offences and problems as they arise (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2004, Reference Hopkins2009). To date, use of RA has produced promising findings in various settings including schools, where it has been linked to better communication, improved learning, increased pupil responsibility and greater empathy (Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd, McCluskey, Riddell, Stead, Weedon and Kane2007; McCluskey et al., Reference McCluskey, Lloyd, Kane, Riddell, Stead and Weedon2008), children's residential homes where it has led to decreased contact with the justice system (Willmott, Reference Willmott2007), and in communities where adoption has improved cohesion and reduced conflict (Fives et al., Reference Fives, Keenaghan, Canavan, Moran and Coen2013).

Use of RA as a framework for delivering UK early intervention family services is growing, but knowledge of its impact on service delivery and effect is sparse. Much existing pertinent evidence comes from use of the associated restorative practice of Family Group Conferencing (FGC) which has been associated with some reduced use of aspects of child welfare and protection systems in parts of the world (Burford and Hudson, Reference Braithwaite, Burford and Hudson2000; Pennell and Burford, Reference Pennell and Burford2000)). Similar knowledge of RA efficacy in family services is thwarted by lack of evidence from experimental or quasi-experimental studies with most accounts of use found in the grey literature. This lack extends the problem of a dearth of evidence of the sustained effects of wider early family interventions (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Smailagic, Huband, Roloff and Bennett2012) to RA, and leaves calls for governments to limit endorsement to evidence based interventions or programmes (Save the Children, 2010) further unmet.

Whilst it can be argued that this position demands a body of robust research to explore RA adoption in early intervention family services, concerns about adopting restorative practices in new settings without fully understanding their processes and implementation have been voiced (Greene, Reference Greene2013). Indeed, such anxieties are echoed by those who note the lack of implementation science in the associated field of Family Decision Making Conferences (which include FGC), who contend that this muddies the interpretation of results and ignores opportunities to improve knowledge of what works and so improve outcomes (Merkel-Holguin and Marcynyszyn, Reference Merkel-Holguin and Marcynyszyn2015). These concerns are likely to apply equally to use of a RA within family services, as different RA models are developed and taught and no evidence of using theoretical implementation frameworks (e.g. Glasgow et al., Reference Glasgow, Vogt and Boles1999; Rogers, Reference Rogers2003) to direct evaluation and assess effect in a systematic way found.

In sum, this situation suggests that a corpus of experimental work could be usefully prefaced by some theoretical consideration of RA, of how this approach maps onto family service delivery and receipt, and whether it has potential to influence them positively. This article seeks to undertake this conceptual deliberation. To do so it draws on existing literature to define RA, explore its theoretical foundations and consider how this maps onto current recommendations for early intervention family service provision in the UK. To aid this exercise, models of RA and of multi-agency family service delivery with a RA framework will be constructed with the purpose of stimulating and aiding discussion around whether and how RA has the potential to improve multi-agency early intervention family service organisations, delivery and effect in the UK and wider.

The roots of a restorative approach

RA is closely allied to Restorative Justice, a practice linked to ancient methods used in Native American, Aboriginal, Maori and other indigenous communities (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2004, Reference Hopkins2009; Gavrielides, Reference Gavrielides2007; Wachtel, Reference Wachtel2013). Restorative Justice was developed in the 1970s in response to calls to involve victims more closely in addressing crimes (Van Ness, Reference Van Ness2005; Zehr, Reference Zehr2015), and criticisms of systems that removed the justice process from those most affected, to award it to the state (Daly, Reference Daly2001).

Masters (Reference Masters and Hopkins2004) contends that Restorative Justice draws on a number of specific practices: ‘face to face’ victim offender meetings in the criminal justice system in Canada, Family Group Conferencing in New Zealand; the scripted conference model in Australia; and sentencing circles as used by the First Nation in Canada. Collectively these practices inform a process in which an offender, the victim, and others affected by a crime or injustice take part in facilitated discussions in which participants acknowledge the crime and its consequences, before considering how these can be resolved and resultant harms repaired (Zehr, Reference Zehr2002). Through this process Restorative Justice seeks to foster changes in the determinants of injustices in a way that is characterised by the involvement of the community affected by the crime (Braithwaite, Reference Braithwaite2002).

Restorative Justice is governed by theory based on the principles of collaboration, self-determination, flexibility, voluntary participation, adherence to fairness, unbiased, non-discriminatory and respectful attitudes and use of honesty, humility, mutual care, and trust between those involved (Restorative Justice Council, 2013; Restorative Justice Network, 2003; Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2009). The process of Restorative Justice revolves around two constructs: a tangible procedure and the principles described. Whilst the relative importance of both remains debated (Daly, Reference Daly2001; Zehr and Mika, Reference Zehr, Mika, McLaughlin, Fergusson, Hughes and Westmarland2003), some view them as intrinsically linked and mutually reinforcing, arguing that the process of Restorative Justice is but an expression of the underlying values (Restorative Justice Council, 2013; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2006). To date, Restorative Justice has proved effective in reducing levels of reoffending and achieving some reparation for victims in many parts of the world (Sherman and Strang, Reference Sherman and Strang2007).

Description of RA (also termed restorative practice) as the adaption and application of Restorative Justice to community/organisational contexts (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2004, Reference Hopkins2009) extends the concept beyond penal reforms to govern a way of living and addressing conflict in all conditions (Greene, Reference Greene2013). The online literature offered by a number of agencies which provide commercial RA training (e.g. Transforming Conflict, The Restorative Justice Council) supports this opinion as it emphasises how use of RA in wider settings requires an understanding and application of Restorative Justice principles. However, whilst RA shares the values of Restorative Justice it is distinguished by the contexts it can be employed in and the rationale for its use. The next section will consider RA, its theory, value base and practice.

A restorative approach

The values underlying all restorative practices support a general consensus they include the repair of relationships and harm, community reintegration, community development, shared learning, forgiveness and love (Braithwaite, Reference Braithwaite, Burford and Hudson2000a). Theorists opine that these values are built on democratic principles which believe communities are strengthened by practices that place responsibility for solving problems with those affected. Further, they argue that restorative practices rest on a collaborative, partnership-based, inclusive approach that shares power fairly between state, family and community representatives and resources, believing that if this is achieved such practice systems can promote human rights, social justice, and give voice to those often unheard (Burford and Hudson, Reference Braithwaite, Burford and Hudson2000).

However, as yet theories, models, definitions and explanations of RA that set out the operations through which it effects change are unclear. Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2016) made effort to clarify these in an edited volume that brings together restorative experts and asks them to set out the pathways through which each believes RA effects change. Contributing authors draw on a range of biological, social and psychological arguments, including theories of: attribution (Starbuck, Reference Starbuck and Hopkins2016); affect and motivation (Thorburn, Reference Thorburn and Hopkins2016); personal construct (Denicolo, Reference Denicolo and Hopkins2016); conflict and human relationships (Shearer, Reference Shearer and Hopkins2016) and social construction (Drewery, Reference Drewery and Hopkins2016). Whilst interesting, the various varied explanations can cause confusion, and a later section in which the commonalities between these theoretical processes are identified is arguably more helpful as it turns attention to a higher level theory of behavioural change. In this, contributors argue that RA effects change by drawing on innate human needs that encourage individuals to connect with each other and attempt to understand the determinants and effects of behaviours. Further, authors contend that fulfilling this need engenders increased empathy, compassion, kindness and generosity in those involved and this, in turn, motivates a desire to amend matters thereby satisfying another innate yearning for justice. Herein the authors add detail to the more common definition of RA as an ethos and practice that works by building, maintaining and sustaining relationships, by providing a rationale for why people tend to respond positively to restorative approaches, and describing how the process stimulates changes in cognition and actions.

Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2004; Reference Hopkins2009) turns attention to the practicalities of using RA by conceptualising a pyramid that links restorative values, skills and outcomes. The pyramid is supported by a base consisting of restorative values and the associated themes of: respect and appreciation for individual accounts, commitment to developing mutual understanding, a focus on the harm caused and how to repair it, appreciation of individual needs, and a shared accountability for resolving matters. This base supports a smaller ‘skills’ section, which draws on and is made effective by using and meeting the values and themes. The skills consist of good communication skills, the ability to create a safe environment for those participating, and working in a non-discriminatory manner. The pyramid is topped by an apex representing the hoped for outcome of restorative processes, better interaction and resultant changes.

Whilst the pyramid is applicable to all restorative practices, it is important to appreciate the differences in varied approaches. Restorative Justice is a more reactive process employed to address and resolve crises or crimes/offences. In contrast, a RA works on two related levels. The first consists of restorative values and skills which can be applied widely, holistically and proactively in organisational, group and community settings, to improve the day to day interactions, relationships and environments of those who live or work in them. The second is concerned with employing restorative principles and skills reactively and as needed to resolve conflict and solve problems as they occur within settings (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2009). Costello et al. (Reference Costello, Wachtel and Wachtel2010) offer a restorative continuum that represents and links these different levels, moving from an ‘informal’ adherence to principles that promotes active listening, creates empathy and encourages collaboration, to formal resolutions that include restorative circles, mediation or full restorative conferences as needed and chosen (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Restorative practice continuum

Wachtel (Reference Wachtel2013) gives more detail of how this operates, explaining how when conflict arises, RA can move up the scale by actioning a set of affective or ‘restorative’ enquiries that can facilitate behaviour changes. These are outlined in Table 1.

It is also important to appreciate that even when used reactively, RA differs from Restorative Justice as it works from a stance that addresses problems by building better relationships and achieving positive behaviour changes in ways that concentrate on the problem rather than the person (McCold and Wachtel, Reference McCold and Wachtel2003, Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2004, Reference Hopkins2009). Costello et al. (Reference Costello, Wachtel and Wachtel2010) deflect criticism that this approach is too weak or accepting by applying the values of control and support to restorative practices. From this perspective, the value of control imposes boundaries set by community/social norms and expectations, whilst sustained support ensures that all receive continual encouragement and a feeling of being valued. Costello et al. use these principles as the cross axis frame of the ‘social discipline window’, a conceptual framework of four sections that represents working relationships based on different combinations of high and low control and support. Within this structure RA sits in the quadrant made up of high control and high support (doing things with people), as opposed to the non-restorative sections of high control and low support (doing things to people), low control and high support (doing things for people), and low support and low control which is essentially not doing anything to promote change.

Drawing on the key concepts and theories outlined above, RA can be defined as an ethos founded on values such as fairness, participation, inclusion, and support that can build and strengthen communities, and which can be drawn on to shape a process that resolves arising problems by bringing those involved together and repairing the damaged relationships by increasing mutual understanding, generating motivation to remedy matters, and providing support needed to remedy the issue as far as is possible in a way acceptable to all.

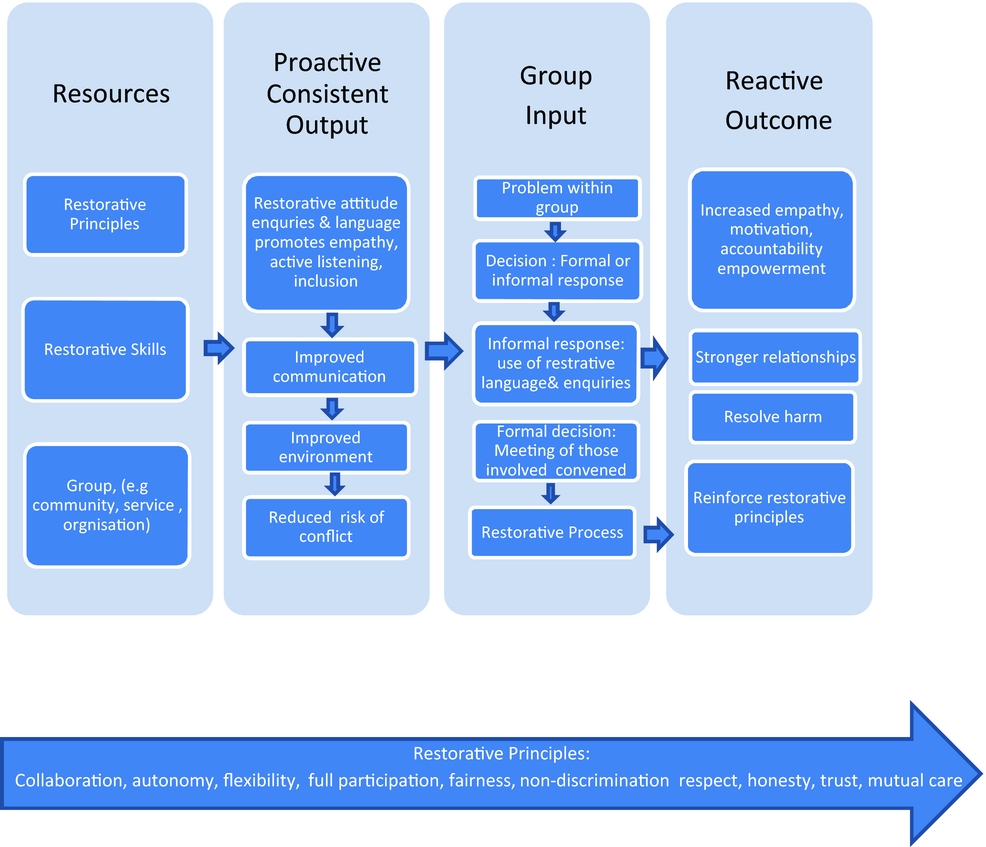

Describing RA this way identifies integral stages that are analogous with other behaviour change methods that have been employed effectively in varied settings, including family services. Braithwaite (Reference Braithwaite2011, Reference Braithwaite2016) has commented on the ways in which both motivational interviewing and restorative practice help people uncover personal incentives to change. Restorative practices have been associated with cognitive behaviour in recognition that both increase understanding of why behaviours have occurred, an understanding which can change perceptions of one another's motivations and behaviours (Sherman et al., Reference Sherman, Strang, Angel, Wood, Barnes and Bennett2005). The collaborative discussions of goals and how to achieve them is reminiscent of solution focused therapy, which has been used to help achieve change with families elsewhere (e.g. Forrester et al., Reference Forrester, Holland, Williams and Copello2016). It has also been argued that RA can encourage change through consistent experiences of careful listening, discussions and goal planning with full inclusion that gives ample opportunity for social learning (Macready, Reference Macready2009). Viewed from this perspective RA is a system made up of consistent values, language and attitudes, that builds positive environments and better relationships, but can also address problems and conflicts through a fair, inclusive and honest process that harnesses and expedites recognised behaviour change mechanisms. Figure 2 represents this process.

Figure 2. A model of restorative approach

Attention now turns to how RA maps onto family service provision in the UK.

Use of restorative approaches in early intervention family services

As noted, although the lack of peer reviewed literature related to RA in early intervention family settings indicates a paucity of research in this area, the knowledge base around FGC is pertinent as the practice applies restorative principles to family welfare albeit mainly in child protection arenas.

FGC is a restorative practice that was introduced into New Zealand child protection services in 1989, after being developed from local intrinsic Maori culture and practices. FGC was formulated to challenge the more authoritative child protection services in New Zealand of that time, and did so by introducing a democratic, partnership-based system that worked by gaining better understanding of family situations, increasing feelings of responsibility and harnessing family capabilities to address concerns (Burford and Hudson, Reference Braithwaite, Burford and Hudson2000). FGCs were first actioned as part of a legal process that brought families and professionals together to discuss and resolve child protection concerns and form child safety plans (Levine, Reference Levine2000). FGC became linked to reduced child removal into state care (Maxwell and Morris, Reference Maxwell and Morris1992; Burford and Hudson, Reference Braithwaite, Burford and Hudson2000; Pennell and Burford, Reference Pennell and Burford2000; Sheets et al., Reference Sheets, Wittenstrom, Fong, James, Tecci, Bauman and Rodriguez2009) and sparked wider global attention, especially in communities and nations with similar indigenous practices (Nixon et al., Reference Nixon, Burford, Quinn and Edelbaum2005). Many subsequent findings have strengthened early findings (e.g. Kiely, Reference Kiely2005; Titcombe and LeCroy, Reference Titcombe and LeCroy2005; Marsh, Reference Marsh2013). Further work has associated FGC with a number of additional positive effects including: increased family feelings of support when involved with children's services (Horwitz, Reference Horwitz2008); increased support from extended families (Gunderson et al., Reference Gunderson, Cahn and Wirth2003; Koch et al., 2006; Morris, Reference Morris2007); greater satisfaction with services (Burford and Hudson, Reference Braithwaite, Burford and Hudson2000); financial savings due to reduced care entry (Marsh, Reference Marsh2013); and reduced child maltreatment (Titcomb and LeCroy, Reference Titcombe and LeCroy2005). Despite this, some studies have demonstrated little impact of FGC on child protection re-referrals rates (Sundell and Vinnerljun, Reference Sundell and Vinnerljun2004), whilst others argue that FGC effect is influenced by recipient social, cultural and organisational norms (Nixon, Reference Nixon, Burford and Hudson2000). This latter contention is supported by the history of the adoption of FGC in the UK, which commenced in the 1990s (Holland et al., Reference Holland, Scourfield, O’ Neill and Pithouse2005), a time when the participatory principles of FGC aligned closely with the recently implemented 1989 Children's Act (Nixon, Reference Nixon, Burford and Hudson2000). Despite this, the introduction of FGC met resistance at different levels. First, FGC did not achieve legislative status; instead government guidance recommended its use in instances without child protection concerns or alongside rather than instead of standard child protection processes (Nixon, Reference Nixon, Burford and Hudson2000; Holland et al., Reference Holland, Scourfield, O’ Neill and Pithouse2005). Further, FGC elicited professional concerns around increased levels of risk alongside a reluctance to shift the power balance so far towards families (Nixon, Reference Nixon, Burford and Hudson2000). Today FGC in UK child protection and wider family welfare systems is not mainstream, and spaces for parents, families and friends to speak freely in welfare system arenas are still described as ‘fragile’ (Featherstone et al., Reference Featherstone, White and Morris2014).

This brief consideration of FGC illustrates how it brought restorative principles into family settings. Emerging accounts (e.g. Kay, Reference Kay2015; Finnis, Reference Finnis2016; Bright, no date) indicate that innovative applications of RA are currently bringing restorative practices into different levels of family service delivery. Some such accounts also infer that introducing RA into family services can work to align practice delivery with that recommended and promoted by family policies across the UK (e.g. Welsh Government, 2011; DCLG, 2012).

UK early intervention family support services

As noted when discussing FGC many calls to reorganise existing children and family services over the last few decades were triggered by a desire to challenge the dominance of interventional practice determined by professional experts, and meet attendant demands for more empowering practice and a re-balancing of power differentials (e.g. Dominelli, Reference Dominelli2002; Featherstone et al., Reference Featherstone, White and Morris2014). Some such demands were articulated during a time that saw the emergence of new prevention/early intervention UK family programmes such as Sure Start and the Children's Fund, which sought to meet family needs better through packages of cross-sector multiagency services working at a family rather than individual family member level. These programmes illustrated an important shift in central UK government policy with greater recognition of the complex socio-ecological forces that can prejudice the welfare of children and families living with disadvantage. Intervening years have given opportunity to evaluate and analyse these and other UK family services, and relate them to wider international evidence (Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Rodger and Palmer2010; Scott, Reference Scott, Arney and Scott2013). At present, opinion suggests that effective early intervention services are based around key elements:

• A commitment to prevention

• Service provision in the early years of a child's life

• Continued commitment to the provision of early intervention services in later years

• Multi-agency approach

• High quality work force

• Investment in programmes that work

Frost et al., Reference Frost, Abbott and Race2015

Further factors have been identified. These include infrastructural factors that call for improved interagency communication, integration, collaboration, accessibility and flexibility (Luckock and Briant, Reference Luckock and Briant2002; Dahl et al., 2005; Howarth and Foreman, Reference Howarth and Foreman2006; Spicer and Smith, Reference Spicer and Smith2006) and service delivery factors that demand use of empathetic, family-focused, strengths based, respectful, positive ways of working (Dunst et al., Reference Dunst, Trivet and Hanby2007; Forrester et al., Reference Forrester, Holland, Williams and Copello2016). Collectively these show renewed appreciation of the importance of a central restorative tenet: the importance of good relationships between organisations, practitioners and clients (e.g. Munro, Reference Munro2011; Scott, Reference Scott, Arney and Scott2013; Frost et al., Reference Frost, Abbott and Race2015). Further emphasis on these can be found in guidance for some major ongoing UK family programmes (e.g. Welsh Government, 2011; DCLG, 2012) which call for better interagency integration and systematic use of ‘family-focused’ and ‘whole family approaches’ within service delivery. When reflecting on what these mean and how they relate to restorative principles, Hughes (Reference Hughes2010) has helped by categorising common UK family service delivery methods into three models. The first focuses attention on one primary service user, and the ability of the wider family to support them; the second treats family members as service users in their own right but still concentrates on helping them support the primary service user; the final ‘whole-family approach’ (WFA) works at the collective family level directing attention to the needs and strengths of the group (family) unit and building resultant services around these. Whilst all models require a good working relationship with families, WFA requires more extensive knowledge of the family and family needs, it also has a wider remit as it seeks to elicit change at the family level and build resilience and social capital within the family system (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Hughes, Clarke, Tew, Mason, Galvani, Lewis and Loveless2008; Hughes, Reference Hughes2010).

Despite these advances, any complacency stemming from increased recognition of the important facets of family care provision and their ability to increase service effectiveness is challenged by suggestions they are not yet faithfully and reliably reproduced in the UK. Efforts to implement such models are tested by the different socio-demographic profiles family programmes serve, the impact of declining UK financial resources, and the current existence of different central and devolved governments with varied family service policies. In regards to the latter, although Welsh policy emphasises service provision at the family level (Pithouse and Emlyn-Jones, Reference Pithouse, Emlyn-Jones and Vincent2015), with Scotland appearing more child-centred (Rose, Reference Rose and Vincent2015), both appear to embrace a strengths-based high support approach in principle. This contrasts with some rhetoric around the Troubled Families programme in England which attributes the programme need to poor parenting, anti-social families and delinquency, thus reinforcing the concept of individual pathology, placing responsibility with the family, and ignoring wider determinants (Crossley, Reference Crossley2015). Further caution must be exercised when assessing progress in family service provision in the UK more widely. Even with best intent, translating policy into early intervention family programmes using more proactive strength-based approaches in an embedded holistic way is not easy. Reports related to the recent adoption of an early intervention multi-agency family programmes in Wales refer to how efforts to adopt and embed more collaborative inter-organisational practice have been hampered by different professional cultures and practices (Welsh Government, 2013, 2014), whilst Munro (Reference Munro2011) attributes family failure to engage in services to fractured relationships with key professionals and a sense of lost empowerment and autonomy.

This situation leaves space for the consideration of whether other methods have the potential to develop, implement and provide family services in a way that promotes interagency collaboration, embeds use of whole family approaches, and addresses some of the wider social determinants of family difficulties. The next section explores this by considering delivering family services using a RA framework and whether this has the potential of improving current family service provision.

Restorative approaches in multi-agency family support services

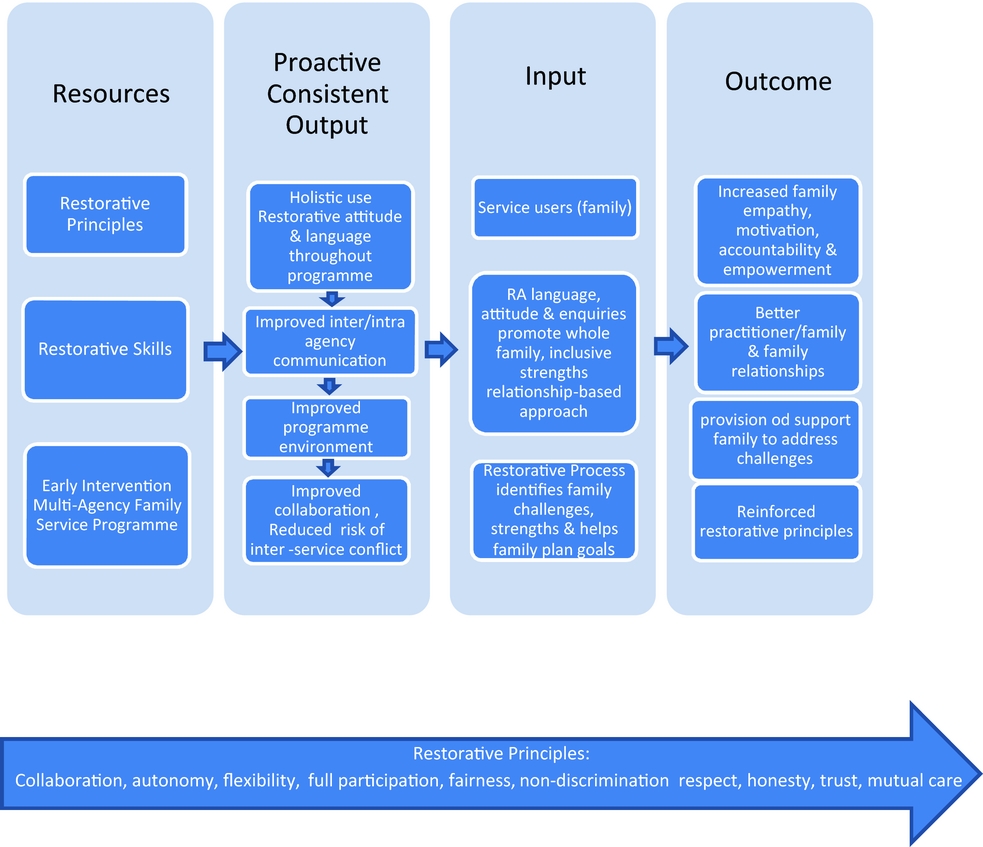

Claims that RA can resolve and prevent harm by building and sustaining relationships within institutions, communities and between individuals suggest it may positively impact on early intervention multi-agency family service systems at organisational, service provision and receipt levels. The following section discusses the potential impact of RA on multi-agency family services by drawing on empirical and conceptual literature. Figure 3 maps the concept of RA onto UK multi-agency family service provision as currently recommended.

Figure 3. Restorative multi-agency early intervention family services

At organisational level there is evidence that the adoption of RA by multi-agency programmes working with disadvantaged communities is feasible and has helped move services closer to recommendations by improving inter-agency interactions, communication and integration, and increasing staff feelings of responsibility and accountability (Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Johnstone, Green and Shipley2011; Fives et al., Reference Fives, Keenaghan, Canavan, Moran and Coen2013). An account of adopting RA within a statutory UK Children's service organisation (Tariq, Reference Tariq2016) takes these claims further, linking RA to better intra-agency consultation, improved managerial knowledge of facilitators and barriers of best practice, and a more positive, productive workforce. Collectively, this provides evidence that RA can improve relationships within and between agencies via an ethos and process that advocates regular discussions, increases mutual understanding and identifies necessary changes; whilst maintaining organisational and service collaboration and cohesion. This indicates that RA adoption has been successful in overcoming organisational and structural barriers, thus facilitating changes that can lead to better ‘joined up’ working and increased service effectiveness (Moore and Fry, Reference Moore and Fry2011). However, the experiences cited also suggest caution: Tariq (Reference Tariq2016) advises that adopting RA requires good leadership, whilst Lambert et al. (Reference Lambert, Johnstone, Green and Shipley2011) warn that acceptance can be slow and need sustained effort as organisational resistance can be encountered. Despite this, both sources agree that RA has been generally accepted, embedded, seen positively and provided diverse professionals with a common connection, language and set of processes.

Considering adoption of a RA at provider level theoretically, the values supporting RA suggest that its adoption as a framework for family service provision maps well onto early intervention family service provision as advocated by existing literature and UK early intervention family programme directives. More specifically, the RA ethos would promote interactions shaped by collaboration, trust, autonomy, flexibility, voluntary participation, and delivered using fair, honest, unbiased, non-discriminatory and respectful attitudes (Restorative Justice Network, 2003; Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2009). The RA model of delivery would also promote inclusive, family–focused, participatory, strengths-based relationship-based practice as the process would promote communication with and within families, elicit information about the family situation from all, and help form a shared understanding of family problems and how people were affected, thus building family and individual motivation to change. The later phases of RA which revolve around collaborative family-led discussions of what and how to achieve changes are goal orientated and solution focused, and therefore likely to build family autonomy, confidence and resilience if they lead to successful outcomes. In addition, consistent use of RAs by all multi-agency service providers promises to lead to repeated, more positive experiences of service receipt which may move some families closer to their communities as evidenced elsewhere (Macready, Reference Macready2009; Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2009). This may address feelings of exclusion generated by previous negative experiences of service use (Forrester et al., Reference Forrester, Holland, Williams and Copello2016) and, over time, allow families to revise pre-existing negative opinions of authorities and reduce alienation from services and the systems they represent.

Potential challenges

Use of a RA within multi-agency family services is likely to face challenges at organisational, and practice levels. First, negative reactions to FGC in the UK and wider (Nixon, Reference Nixon, Burford and Hudson2000; Ney et al., Reference Ney, Stoltz and Maloney2013) suggests resistance may be found to other restorative practices in some family service organisations or agencies, especially in today's UK social welfare climate where authoritarianism persists in many social work organisations (Featherstone et al., Reference Featherstone, White and Morris2014). However, as introducing RA into early-intervention family services involves using the approach in situations in which service use is not mandatory and engaging families is essential, more positive responses may emerge.

At service delivery level, questions have been raised about whether it is possible to teach practitioners the values and attitudes needed to use people-centred skills or if these are qualities built from experience or possessed innately (Goodman, Reference Goodman2011). This is an important point to consider as failure to adopt and use a RA holistically across all sectors and agencies may seriously reduce effectiveness and fail to test the theory that social exclusion can be reduced by moving individuals closer to social systems (Le Grand, Reference Le Grand2003). When reflecting further on delivering family services using RA other problems may be faced if bringing families together to address problems is inadvisable or infeasible, although working with individual family members to achieve positive changes on a one to one level or to reach a point where they may be able to join the group is possible.

A wider systems concern is the possibility that RA adoption is limited to service provision rather than organisational change. If so, RA may reinforce tendencies to focus on changing families and strengthen the practice of blaming individuals whilst ignoring wider societal forces that sustain inequality. It would also miss an opportunity to replicate and explore the impacts of RA on agency collaboration as described by Lambert et al. (Reference Lambert, Johnstone, Green and Shipley2011) and the redistribution of power within organisations as reported by Tariq (Reference Tariq2016).

Finally, the sustained debate on how democratic RA really is (Daly, Reference Daly2001; Gavrielides, Reference Gavrielides2007) raises questions about how participatory and collaborative a process that tries to bring the behaviours of ‘offenders’ closer to a norm decided on and decreed by authorities can be. This is especially relevant when RA is introduced to services in a society that clings to the notion of ‘failing families’, at least to some extent.

Conclusion

This article explored the concepts and theory of restorative justice, restorative approach and effective family service provision before considering the potential impact of RA on early intervention multi-agency family services. Overall, the process suggests that RA possesses potential to improve UK family service systems and methods by improving communication, building better relationships and providing support which enables individuals, families and organisations to identify and achieve necessary changes in a positive way. Although adopting RA throughout a multi-agency family service system would be a large undertaking requiring systemic and systematic changes at multiple levels, the literature indicates that this has already been attempted and achieved to various extents as illustrated in settings where it has had a positive impact on organisational and staff patterns of communication, interactions and working. In addition, RA appears to offer a way of working with families that pulls together a set of evidence-based interventions, placing them in a systematic process that employs a whole family, relationship based, participatory, strengths based approach in a family service delivery setting against a background of more collaborative, integrated multiagency programmes. However, the scarcity of robust evidence around use of RA in complex family service contexts calls for further evaluation of its use within family services to give empirical insight into whether early intervention multi-agency family services and the families using them can benefit from the adoption and use of RA as both an ethos and method.

Acknowledgements

The work was undertaken with the support of Health and Care Research Wales, CASCADE the Children's Social Care Research Centre at Cardiff University, and The Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer), a UKCRC Public Health Research: Centre of Excellence. DECIPHer gratefully acknowledges funding from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council (RES-590-28-0005), Medical Research Council, the Welsh Government and the Wellcome Trust (WT087640MA), under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration.