Я сижу и смотрю в чужое небо из чужого окна I sit and look at an alien sky through an alien window

И не вижу ни одной знакомой звезды. And don't see one familiar star.

Я ходил по всем дорогам и туда, и сюда, I walked all the roads, both there and back,

Обернулся—и не смог разглядеть следы. Turned around, and couldn't see my footprints.

—Kino, “Pack of Cigarettes” (1989)I can attest to the glares and threats one can receive as a racially marked foreigner in Russia, or when passing as someone from the former Soviet periphery. However, in Moscow or St. Petersburg, hearing Viktor Tsoi and his band Kino played or covered on the street was always strangely assuring. The fact that the late-Soviet period's most prominent rock star—an enduring cult figure long after his 1990 death by car crash at the age of twenty-eight—happened to be half-Korean was somehow a source of comfort. This may seem irrational, since listening to minority musicians is no reliable foil against racism, and in any case one would be hard-pressed to locate any “Korean” form or content in his work. It would be speculative to hear his song about the “trolleybus which heads to the east” as a reference to Asia, or his playful “Kamchatka” as a reference to the Russian Far East rather than the eponymous Leningrad boiler room where he worked and held concerts.Footnote 1 Among his contemporaries, discussion of his Asianness tends to be cursory and superficial, limited to his idolization of Bruce Lee and enjoyment of Asian food.Footnote 2 Accordingly, a 1987 short story written by Tsoi registers at best an ambivalent relationship with Asia: its protagonist believes that the only “acceptable path is to achieve the peaceful relationship with death and eternity proposed by the East,” but finds this thought “unbearably boring” and ultimately achieves a newfound embrace of life.Footnote 3 In one 1990 interview, Tsoi himself claimed that as a native Leningrader, he had no connection to Korea, but added that “probably some genetic connection remained, possibly manifesting in my interest in Eastern culture.” In another 1990 interview, while spurning ethno-nationalist conflict as unreasonable, he stated that “the national question never stood before me in any form.” His passport registered his nationality as Russian, following his mother. However in the same interview he again muddled matters by adding, “I don't consider myself culturally Russian. I'm an international [internatsional΄nii] person (he laughs)”—here ironizing a term long defined in the USSR as “close ties among Soviet nationalities.”Footnote 4

The aim of this article is not to pin down Tsoi's identity but to unpack the difficulty of pinning him down, which is reflected in his popularity across national and political boundaries. Kino songs and covers have played at both pro- and anti-Putin rallies; at the 2020 protests in Belarus and at Euromaidan in 2014, but also Russia Day concerts on Red Square and events celebrating the annexation of Crimea.Footnote 5 Such broad appeal speaks to Tsoi's ability to eschew binaries—an ability common, as we will see, to what Alexei Yurchak has described as the “last Soviet generation,” but which, in contemporary Russia, has congealed into a belligerent nationalism that we can only hope will pass. By examining the Tsoi of late socialism as a reluctant national minority—what I will be calling his “deterritorialized nationality”—this article seeks to foreground radical internationalisms that help us to think beyond the renewed polarization of Russia and the west, as well as the ever more polarized discussions surrounding identity in the west. I will begin by discussing Tsoi and the 1980s Leningrad rock scene with the help of Yurchak's account of late-socialist deterritorialization, that is, the last Soviet generation's ability to operate simultaneously within and beyond official discourses. I will then turn away from Tsoi to show how particularly for Soviet Koreans, deterritorialization enabled open-ended understandings of identity that both drew from and eschewed state nationalities policy.Footnote 6 The bulk of the article will then focus not so much on Tsoi himself, but on his representation in film as well as the reception of these films to highlight a common language for discussing identity across east and west—ultimately, a bridge between late socialism and Birmingham School cultural studies, which in the 1970s and 80s used youth subcultures to connect race, class, and gender in ways conducive to cross-group coalitions. The keystone for this bridge will be Tsoi's traversal of alien terrains without leaving footprints, as expressed in the lyrics above—ways of being visible as a minority that eschew fixed interpretations, and that bring into focus the now-foreclosed possibilities of the perestroika period.

Summer, Kirill Serebrennikov's 2018 biopic about Tsoi and Zoopark's Mike Naumenko, showcases that period's utopian charge through a self-consciously nostalgic haze, one that highlights the gap between the hopes of late socialism and the moribund post-socialist present.Footnote 7 Specifically, the film conveys the sense of a world opening up through music: from concerts at the Komsomol-run, KGB-supervised Leningrad Rock Club, where the artists push against state-imposed limits that the viewer knows will crumble; to an idyllic seaside picnic and acoustic songs among friends, culminating with a beach bonfire and nude frolicking in the Baltic; to a dream performance of the Talking Heads’ “Psycho Killer” amid a clash with anti-rock conservatives on a commuter train, bystanding passengers singing along. Tsoi appears as a taciturn force of nature, standing apart from, even a bit indifferent to the seaside group, but then winning both Naumenko's tutelage and Naumenko's wife's affections through his song-writing prowess. The film well captures the cultish mythology that has long surrounded him: Tsoi as an outsider among outsiders, whose raw talent brought him to the forefront of the 1980s Leningrad rock scene. However, though he is the only character in the film racially marked as a minority, Tsoi's Korean background is never addressed in the dialogue or love-triangle plot; the film does not explicitly attribute his outsider status to it.Footnote 8 This is not meant to critique Serebrennikov, since the elision can be seen as faithfully expressing Tsoi's own reticence about his background. The absent presence of Tsoi's minority status instead reinforces the difficulty of discussing his Koreanness without seeming reductive, even as it is impossible for viewers not to register it.

This is where Yurchak comes in handy: I would like to suggest that his account of late-socialist performance—as described in his Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More (2005)—helps us to unpack not only the utopian charge surrounding groups like Kino in the 1970s and 80s, but also Tsoi's minority background and its cinematic representation. For Yurchak, what distinguished the last Soviet generation was its ability to use the ritualized and repeated forms of Soviet society to open up “spaces of indeterminacy, creativity, and unanticipated meanings.”Footnote 9 That is, the performative dimension (for example, the ritual of voting in a fixed election, and the context and conventions compelling one to perform this ritual) made it possible to render the literal meanings of the constative dimension (for example, the result of said election) “open-ended, indeterminate, or simply irrelevant.”Footnote 10 In accordance with John Austin's work on performative speech acts, official rituals were performed in ways that were either felicitous or infelicitous—that is, successful or unsuccessful in following established forms—rather than true or false. Felicity in turn enabled individuals to produce “multiple deterritorialized publics” rather than “static public spheres.”Footnote 11 Deterritorialization here means the displacement of authoritative discourses from within: “the routine replication of the authoritative symbolic system” in ways enabling “new, unpredictable meanings that went beyond those that were literally communicated,” as well as “new identities, socialities, and forms of knowledge.”Footnote 12 Such discursive flexibility enabled this generation to “preserve the possibilities, promises, positive ideals, and ethical values of the system while avoiding the negative and oppressive constraints within which these [were] articulated.”Footnote 13 Thus, under late socialism, one could avoid being cast as simply either a dissident or conformist, pro-western or pro-Soviet; rather, one could playfully shift authoritative discourses in ways that upended such binaries.

As Yurchak shows, this open-endedness figured into both the underground Soviet rock scene and the Soviet reception of western rock. For instance, he describes how students writing letters to each other in the 1970s interpreted western rock as perfectly compatible with Soviet ideals; how they were able to combine “bourgeois” and communist cultures to articulate optimistic visions of the future. In particular, they were able to discern in western rock echoes of the Soviet avant-garde of the 1920s, and thus combine the persistent “futurist strand of Soviet culture” with what Yurchak calls the “Imaginary West” of late socialism—here referring to the last Soviet generation's ability to use western culture “to imagine worlds that did not have to be linked to any ‘real’ place or circumstances, neither Soviet nor Western.”Footnote 14 According to Yurchak, what made the Russian underground rock scene that emerged in the 1970s exciting was its experimental sound that “came from an imaginary elsewhere and shifted the constative meaning of authoritative discourse.”Footnote 15 As a case in point, he describes how the band AVIA decontextualized Soviet agitprop by mixing “the avant-garde aesthetics of the optimistic 1920s and the frozen ideological form of the stagnant 1970s with elements of punk and slightly erotic cabaret. In AVIA performances up to twenty actors in workers’ overalls fervently marched in columns, shouted slogans and ‘hurray,’ and built human pyramids.”Footnote 16 Such decontextualization of and overidentification with official discourses points to a specific kind of deterritorialization, namely, the ironic aesthetic practice known as stiob, in which it is impossible to discern “sincere support, subtle ridicule, or a peculiar mixture of the two.”Footnote 17 For example, a 1987 Leningradskaia pravda article used formulaic party language to denounce the city's rock subculture, specifically the bands Akvarium and Alisa, but in fact was written by a member of that subculture who had performed with those bands.Footnote 18 Stiob occupied a position both inside and outside of authoritative discourses, in the process underscoring their rigidity.

Yurchak's framework illuminates dimensions of Tsoi's image and sound that would otherwise remain obscure. We can hear the “Imaginary West” in Kino's use of synthesizers and brittle guitar riffs—echoes of western postpunk and new wave, with Tsoi's low singing voice uncannily resembling Ian Curtis’ of Joy Division, and his jerking movements on stage evoking Roger Smith of The Cure.Footnote 19 Stiob seems to be behind the maybe ironic, maybe earnest slogan “We Will Save the World,” printed in white all-caps on the black t-shirts donned by Kino members.Footnote 20 Yurchak likewise helps us to understand the difficulty of casting Tsoi as either dissident or conformist. For instance, the hit song “Changes” can readily be heard as a soundtrack for the Soviet collapse, with its famous refrain proclaiming, “Changes! Are what our hearts demand. Changes! Are what our eyes demand. In our laughter and in our tears, and in the pulse of veins: Changes! We await changes.” However, Tsoi himself did not regard it as a protest song,Footnote 21 and the other verses foreground quiet, everyday details—holding a cigarette with tea on the table, an empty box of matches, the blue light of a gas stove—pointing to the need less for political change than for existential change amid the stagnant circularity of everyday life.

That such details seem in harmony with late-socialist deterritorialization should not be surprising, given Tsoi's prominent place in and for the last Soviet generation. What I would like to add is that deterritorialization also provides us with a historically grounded way to think beyond such binaries as Korean versus Russian, minority versus majority in the late Soviet Union. I am following the lead here of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, from whom Yurchak draws the concept of deterritorialization, and who themselves apply deterritorialization to minority identity—or what they call “becoming-minoritarian”: identity-formation as a process that alters our understanding of both the major and the minor. According to them, “Even blacks, as the Black Panthers said, must become-black. Even women must become-woman. Even Jews must become-Jewish (it certainly takes more than a state). But if this is the case, then becoming-Jewish necessarily affects the non-Jew as much as the Jew. Becoming-woman necessary [sic] affects men as much as women.”Footnote 22 In short, deterritorialization continuously destabilizes and reconstitutes both minority and majority identities.

At first glance, this process might not seem to apply to the Soviet Union, with its assignment of fixed territories to nationalities large and small. However, and in keeping with Yurchak's framework, the contradictions built into official policy from its outset made it possible to view nationality as both essential and irrelevant, eternal and transitory, laying the seeds for deterritorialization. As scholarship on Soviet nationalities policy (especially on its “feast of ethnic fertility” in the 1920s and early 30s) has shown, upon gaining power the Bolsheviks promoted both modernizing assimilation and primordial nationalism—a tension often traced back to Iosif Stalin's 1913 definition of a nation as a stable, historically constituted community of people with a shared 1) language, 2) territory, 3) economic life, and 4) “psychical disposition, manifested in a community of culture.”Footnote 23 Elaborating on this fourth component, Stalin wrote that while “national character” changed with the “conditions of life,” nonetheless “it exists at every given moment, it leaves its impress on the physiognomy of the nation.”Footnote 24 Thus, nations were both fixed and malleable: defined by state-delineated languages, territories, and characters, but then pushed through the stages of Marxist economic development.Footnote 25 Stalin-era film was a key medium for transmitting this policy—with its contradiction/dialectic between “national form” and “socialist content”—into popular consciousness, and perhaps no film was more notable in this regard than Grigorii Aleksandrov's hit musical Circus (1936), which offers a useful precursor and counterpoint to the Tsoi films discussed below. Showcasing, in Richard Taylor's words, “the superior rights afforded to minorities in Stalin's earthly paradise,” the film depicts a white American circus performer and her half-Black toddler finding an anti-racist refuge in the USSR.Footnote 26 At the famous dramatic close, the toddler—played by Jim Patterson, the half-Black, half-Russian son of an African American émigré—is whisked to safety from the woman's German fascist promoter by a diverse Soviet audience: first a Russian woman cradles the toddler and sings him a lullaby. Then she hands him down to a Ukrainian man who sings a Ukrainian translation of the same song. Then down to a Tatar and a Georgian; to the accompaniment of a klezmer fiddle, a Jewish pair, one played by Solomon Mikhoels, who would go on to forge anti-fascist ties with Jewish Americans during World War II but then lose his life amid the postwar “anti-cosmopolitanism” campaign; and a Black man who sings in Russian accompanied by a blues horn.Footnote 27 Alongside the top-down acceptance of miscegenation (as the circus director explains to the grateful mother, the USSR embraces all colors) and despite the audience's modern clothing, primordial differences become frozen in place through language and music.

If Circus reveals how, in the authoritative discourse, nationality was ultimately “mummified” via territory and essentialist approaches to identity, Yurchak's framing opens the possibility that, in late socialism, one could arrive at more flexible, bottom-up understandings of group identity.Footnote 28 In this case, the authoritative discourse would be comprised of the nationality (“Uzbek” or “Jewish,” for example) listed in each Soviet citizen's passport, as well as of official slogans like “the friendship of peoples” and “national in form, socialist in content.” Deterritorialization would involve the performance of these categories and slogans in ways allowing for new meanings. Indeed, post-Stalinist nationalities policy took an open-ended turn after Nikita Khrushchev, in 1961, asserted the existence of a Russian-speaking “Soviet people [narod]” with an eye towards the “rapprochement [sblizhenie]” of nationalities and, after the ultimate victory of communism on a global scale, post-national “fusion [sliianie].” As Jonathan Brunstedt has recently discussed, however, the official policy still emphasized “national flourishing,” in large part to appease the entrenched national elites in each Soviet republic, hence the indefinite forestalling of “fusion.”Footnote 29 Thus, under late socialism, one could oscillate between national and Soviet selves, which as Caroline Damiens writes, fostered the formation of hybrid, fragmented identities: instead of being pushed through linear stages of development (from primordial tribes to modern nations and Soviet people), national minorities could be portrayed as occupying a simultaneity of states that unsettled the very notion of primordial or modern groupings.Footnote 30

This development provides context for Tsoi's above-noted ambivalence about his identity: Tsoi as reluctant to identify as either Korean or Russian. However, before returning to Tsoi, a brief discussion of Soviet Korean history will help bring into focus what I mean by deterritorialized nationality, for the simple reason that this was a nationality famously stripped of territory. Even before the Soviet period, Koreans had long been associated with mobility. Searching for farmland, Korean settlers arrived in the Russian Far East from the 1860s, and though some Russian officials worried about an incursion of the “yellow race,” they accepted the economic benefit that these settlers brought to the region. Nonetheless, from 1886, the Russian state began placing limits on Korean settlement, which as the historians Ivan Sablin and Alexander Kuchinsky note, “followed a trend in the Pacific region, including efforts by the USA government to limit Chinese immigration with the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882.”Footnote 31 Koreans were thus caught up in a global “yellow peril” discourse, but those who had already settled in the region often prospered by the turn of the century. One English traveler in a border village noted the Koreans’ multi-room homes with “papered walls and ceilings, fretwork doors and windows, ‘glazed’ with white translucent paper, finely matted floors, and an amount of furnishings rarely found even in a mandarin's house in Korea.”Footnote 32 Alongside these traditional trappings were brass samovars and candlesticks, as well as pictures of the tsar and Russian icons.Footnote 33 Such cultural syncretism is perhaps to be expected in a borderland region, and indeed, in 1894, when Russian officials discussed how best to integrate Koreans into the empire, one military governor suggested that they be made “part of the privileged Cossack estate” and entrusted with guarding the borderlands.Footnote 34 This never came to fruition, but armed groups of Koreans would circulate across the region's national borders after the Japanese occupation of Korea, when the Russian Far East became a center for anti-imperial activism and partisan raids.Footnote 35

Although many Koreans came to embrace the Bolshevik Revolution and the Comintern as vehicles for national independence, there was a mismatch between this group's mobility and Soviet policy's emphasis on territory. Stalin's 1913 essay had foregrounded territory by promoting regional autonomy “for such crystallized units as Poland, Lithuania, the Ukraine, the Caucasus, etc.” as a key solution to “the national question.”Footnote 36 Though comprised of both majority and minority groups, each region would ultimately dissolve national barriers and unite “the population in such a manner as to open the way for division of a different kind, division according to classes.”Footnote 37 Meanwhile, national minorities within these units would be granted equal rights “in all forms (language, schools, etc.).”Footnote 38 Stalin's emphasis on territory of course anticipated the Soviet Union's division into national republics, and smaller national minority regions within each republic. Accordingly, the early Soviet state promoted Korean cadres and granted the group one small national region and 171 villages, as well as Korean-language schools, a pedagogical institute, newspapers, and a theater.Footnote 39 However, in 1937 the NKVD deported the entire Korean population (approximately 171,000) from the Far East to Central Asia on the premise that they might bolster Japanese interests in the region—either by serving as spies or by provoking the Japanese military to enter the USSR in search of partisans.Footnote 40

According to the anthropologist Hyun Gwi Park, the deportation thus marked the punitive internalization of a border for those “who were accused of blurring the territorial borders” (29). The result was an extreme form of Yurchak's internal displacement and, in turn, a unique instance of the open-ended meanings and identities of the last Soviet generation. As Park writes:

The experience of Koreans largely confirms Yurchak's sympathetic and humanizing interpretation of Soviet socialism. Most Russian Koreans were proud of belonging to the Soviet Union, and ‘the last Soviet generation’ of Koreans truly believed in socialism, as did Yurchak's interlocutors. Yet, as one of the minorities in the Soviet Union, the spatial displacement of Koreans from their homeland (the RFE) to the alien steppe region resulted in a significantly different type of internal displacement. With their forcible deportation and lack of entitlement to any territory-based Soviet administrative structures, Koreans’ internal displacement resulted in a highly flexible economic life based on widespread mobile agriculture and collective, kinship- based temporary groups.Footnote 41

By this account, Soviet Koreans experienced a literal, not merely performative, version of deterritorialization, which translated into specific economic activities that became associated with Koreanness. Park details how, after World War II, Soviet Koreans combined a belief in socialism with a nomadic, semi-private agricultural practice (known as gobonjil) for which they became famous across the USSR, enlisting the labor of countless seasonal harvesters of many nationalities. For Park, such activities reinforce how this largely Russified community tied Koreanness not to any fixed, intrinsic factors, but rather to mobile kinship relations and entrepreneurial endeavors.Footnote 42 Soviet Koreans thus exemplified late socialism not only by sidestepping binaries like dissident versus conformist, but also by revealing the fluidity of Korean nationality. Lacking a fixed territory—indeed, deported from the border regions that it once possessed—this group found itself both inside and outside of (in the sense of Yurchak's “vnye”) Soviet nationalities policy.Footnote 43

Thus, it is difficult to pin down Soviet Korean identity in general, not only Tsoi's half-Koreanness. His family's history reflects this difficulty, bolstering Park's point about Soviet Korean mobility. In Vladivostok before the deportation, Tsoi's paternal grandmother sang in a Korean choir that was broadcast over state radio—a clear instance of Soviet nationalities policy's promotion of minority cultures. After arriving in Kazakhstan, his paternal grandfather graduated from a local university (where he was “a model student: excellent grades, athletic, a Komsomol member”) and in 1943 began a lengthy career as a counter-intelligence officer for the NKVD, the same commissariat that executed the deportation. In the 1950s he was briefly deployed to Sakhalin, presumably to work with the Koreans that the Soviets inherited there from Japan after the war.Footnote 44 Tsoi's father was born in Kazakhstan the year after the deportation, eventually making his way to Leningrad as an engineer. In short, Tsoi came from a successful, upwardly mobile family, one not simply oppressed by the state and defined as such.

Returning at last to Tsoi's image and sound, my focus will be on his appearance in the films Assa (1987, directed by Sergei Solov΄ev) and Needle (1988, directed by Rashid Nugmanov). These films have frequently been discussed together due to their shared use of previously underground rock music and focus on criminal underworlds. They also have a shared genealogy: Rita Safariants has detailed how Solov΄ev instructed Nugmanov at Moscow's Vsesoiuznyi gosudarstvennyi universitet kinematografii imeni Gerasimova (VGIK, Gerasimov All-Soviet State University of Cinematography)—a creative-pedagogical encounter that drew from the French New Wave and Dziga Vertov, and that emphasized “cinematic playfulness, rule-breaking and experimentation,” including the use of amateur actors like Tsoi.Footnote 45 In turn, Nugmanov was the one who, through his student film documentary project on the Leningrad underground, introduced Solov΄ev to Tsoi. Affirming Yurchak's account of late socialism's discursive flexibility, both films have been read as occupying a space between dissidence and conformism by combining societal exposés with fairytale escapism—the latter taking the form of a demobilizing faith in the Leningrad underground as “genuine and pure” in Assa, and the inexplicably low-key heroism of Tsoi's character in Needle.Footnote 46 As I discuss the films, my aim will be to use late-socialist deterritorialization to open unanticipated meanings around Tsoi's racial otherness, which is visible on screen in ways not possible with music.

Tsoi appears only at the very end of Assa, a crime drama set in a Crimean resort, about an eccentric young artist and musician who goes by Bananan and falls in love with the mistress of an organized crime boss. After the plot's resolution—Bananan has been killed, the mistress arrested after killing the crime boss in turn—the film fades to black, and white lettering announces: “But this is not the end of the story. It would be unfair not to say what happened later. However, everything is just still beginning.” We then see Tsoi, playing himself, applying for a gig at the resort's restaurant with the help of one of the film's main characters, Vitya, a friend and bandmate of Bananan's who happens to be half-African (figure 1) and who is wearing a “We Will Save the World” t-shirt. A bespectacled administrator lists the position's requirements in a monotone: two music diplomas, a music certificate, residency card. “No,” Tsoi responds to each item, noting that he does not live anywhere, with Vitya adding, “He's a poet, he lives on the whole earth [na belom svete].” Dismayed, the administrator then lists the rules and regulations attached to the position, prompting Tsoi and Vitya to exit the office for the banquet hall; and gradually her unfazed voice is drowned out by the opening beats of “Changes.” Already playing in the hall, the other Kino members appear (the guitarist also wearing a “We Will Save the World” t-shirt), and Tsoi, taking the stage, glares through narrowed eyes directly at the viewer as he sings in place, the camera trained on his vibrating head and torso. His sudden jerking movements seem tense and mechanical, his left fist clenching and unclenching while the right grips the microphone, as though he is about to explode. With his British-new-wave-inspired performance style, he himself seems to offer the new beginning promised by the film—a sense of the unfamiliar that Solov΄ev presumably sought to accentuate through what he described as Tsoi's “withdrawn” and “inaccessible” persona, “closed in an Oriental way.”Footnote 47 As the song progresses and the end credits appear, the fourth wall decisively breaks: suddenly we see him performing not in an empty resort hall but a nighttime concert at Moscow's Green Theatre, the camera panning over thousands of candle-wielding fans.

Figure 1. Still from Assa (1987)

The encounter in this scene illustrates well Yurchak's point about the constative and performative dimensions coexisting in late socialist culture—the constative here represented by the rules listed by the resort administrator. However, the fact that she keeps listing these rules even after the two men walk out highlights the open-ended performative dimension: maybe she does this because she is reading and does not see them leave, or maybe she is just following the ritual. In any case, continuing to do so even after they leave adds an ironic dimension to these rules. Meanwhile, at first glance Vitya and Tsoi seem like dissident figures when they walk out on the administrator; the fact that both characters are visibly persons of color in contrast to the white administrator might be seen as a further source of tension. Right before she starts listing the rules, however, the administrator tells them to go to the hall to perform so that she can listen. They are doing what they are told to do, reinforcing Yurchak's argument that the performative dimension was not simply anti-state or anti-socialist. Accordingly, and in keeping with deterritorialized nationality, even as the film seems to foreground racial difference—ending with Tsoi and opening with a saxophone-wielding Vitya singing a rock/disco hybrid entitled “The Boy Bananan”—it quickly asserts the fluidity, even irrelevance of race. In an early scene, Bananan introduces the heroine to Vitya, then asks, “Why are you being shy? Perhaps you're perplexed that he's a Negro. It's nothing [pustiaki]. He's our Soviet socialist Negro. One can say you see before you a Negro of a new formation. Note: not Michael [Maikl], not Joe [Dzho], but Vitya . . . an ordinary Vitya.” Bananan here reveals the place of race in Yurchak's Imaginary West: Blackness as automatically evoking African Americans (with names like Michael or Joe), but then reworked into a new, Soviet racial formation with unexpectedly radical underpinnings. A bit later in the film we learn that Vitya is the son of a tragically deceased Angolan revolutionary, presumably one of the many African students and political figures who spent time in the Soviet Union after WWII.Footnote 48 With this detail in mind, it becomes possible to reread the pairing of Vitya and Tsoi at film's end as an Afro-Asian friendship borne from Soviet outreach to the decolonizing world. That is, Vitya's and Tsoi's racial backgrounds signify not simply the fact of the Soviet population's diversity. The deterritorialization of Blackness here also reveals the history of Soviet-sponsored revolutionary Third Worldism across what is now called the Global South.Footnote 49 The presence of minorities imparts to the film the sense of the unfamiliar and exotic, but in a way that also highlights Soviet ideals about cross-racial, international equality.

Tempering this optimistic Third Worldist reading is the fact that the role of Vitya was filled by a Russian actor in blackface—a far cry from the regimented representation of race in Circus.Footnote 50 Indeed, Assa explicitly distances itself from Circus when Bananan, soon after introducing Vitya to the heroine, quietly sings to himself an adapted line from “Song of the Motherland,” the de facto Soviet anthem first featured in Circus. Instead of the original version's “For us there are no Black people, no people of color [ni chernikh, ni tsvetnykh],” he sings “For us there are no Negroes, no people of color [ni negrov, ni tsvetnykh].” The reference to “Song” is a clear, playful instance of deterritorialization, and I tend not to read Soviet uses of the word “negr” as deliberately offensive. However, given the substitution of the more neutral “Black” by “Negro,” one cannot but be taken aback and confused over whether Bananan is mocking or embracing Soviet outreach to minorities. The confusion is heightened by the fact that Bananan's starring role was filled by the artist and curator Sergei Bugaev, who from the early-1980s went by (and still goes by) simply Afrika—a name coined by Boris Grebenshchikov of Akvarium, at the time enamored with reggae and dub, in response to Bugaev's fascination with Pushkin's (and, thus, Russian culture's) African roots.Footnote 51 Here we see one pitfall of deterritorialized nationality: a fluidity that allows not just for open-ended meanings and aesthetic charge, but also racial appropriation and fetishism. In particular, the blackface, altered “Song of the Motherland,” and name Afrika are all instances of what can be termed “minority stiob”: overidentification with Soviet rhetoric around the “friendship of peoples,” but also as racial and national minorities. As with all stiob, the result is an ability to operate inside and outside of authoritative discourses—in this case, a contradictory nationalities policy and the categories enshrined by it—in a way that wavers between support and ridicule.Footnote 52

I will return to minority stiob below, but first want to foreground a more clearly affirmative instance of deterritorialized nationality by turning to Tsoi's lead performance in Needle, for which he was named 1989 Soviet film actor of the year by the journal Sovetskii ekran. Here again Tsoi is marked as racially different: though a Kazakhstani production set in Kazakhstan, all the main roles besides Tsoi's are played by whites—perhaps reflecting the fact that, for much of the Soviet period, due in large part to the horrors of collectivization, there were more Russians than Kazakhs in Kazakhstan. In the face of this hierarchical history, however, Nugmanov's film eschews national binaries by including multiple languages (in addition to Russian, bits of Kazakh, Italian, French, German, and English), and as Angelina Karpovich has noted, by foregrounding a sense of placelessness vis-à-vis both the Soviet Union and Asia.Footnote 53 Tsoi provides a case in point of this placelessness by demonstrating how one can be or look like an Asian minority without being confined by this designation. He stars as Moro, a black-clad gangster who travels from Moscow to Alma-Ata to collect a debt, finds that his ex-girlfriend Dina is a morphine addict, and goes to battle with the local narco-mafia. To be sure, since he speaks little and conveys few emotions, one could readily stereotype him in the same way that Solov΄ev did: as a withdrawn and inscrutable Asian. In a fight scene, Tsoi seems to engage in martial arts, perhaps reflecting his admiration for Bruce Lee. Throughout the film, his body is simultaneously lithe and restrained; moving slowly and deliberately, but then suddenly flipping beneath a doorway cross-bar (as the Soviet state news theme, Georgii Sviridov's “Time, Forward!,” triumphantly blares in the background), or climbing a wrecked ship in the desiccated Aral Sea.

The character portrayed by Tsoi, however, coupled with the soundtrack's exclusive use of Tsoi's music, grants Needle an ambiguous, contradictory quality that allows for, without being limited by, such racialized readings. The film begins with Moro walking through an alley towards the viewer, while a narrator states, “Nobody knows where he is going, and neither does he” to the accompaniment of the Kino song “A Star Called the Sun.” The song's long-view of history—describing an ancient city under yellow smoke, and pointless wars that come and go—concludes by noting how we are fated to love those who die young, who live by their own rules, and who do not remember ranks, names, or the words yes and no: those “able to reach the stars, not figuring this is a dream.” These lyrics of course feed the mythology surrounding Tsoi—seeming to anticipate his own early death—but they also fit the character Moro. It is unclear why he resides in Moscow and why certain Alma-Atans are indebted to him. His romantic past with Dina and why he chooses to help her are never explained. At one point he boards a train leaving the city until he remembers to return her apartment key, its pendant chiming the theme from the Mickey Mouse Club. Forcing her to break her addiction during a weeks-long escape to the steppe, he seems to understand an elderly man speaking only Kazakh, and for some reason posts in their mud hut a picture of two kitsch cherubs who appear to be South Asian. The film's ending is left open-ended: Dina is back on morphine; Moro, after staring down her dealer/ex-lover, calls to say he is coming to her, but then is stabbed on a snow-covered path to the accompaniment of the song “Blood Type,” the first song of Tsoi's that Nugmanov knew he wanted to use in the film.Footnote 54 To a slow cruising beat and jangling guitars, the lyrics—about street gangs going to battle—emphasize constant movement: from the opening lines (“A warm place, but the streets await the imprints of our feet—stardust on boots”), to the refrain (“Wish me luck in the fight, wish me that I won't get stuck in this ground”), to the final verse (“I would like to stay with you, simply stay with you, but a star high in the sky calls me away”). Accordingly, after kneeling with a lit cigarette lighter, blood dripping on the snow, Moro rises up and keeps walking, this time away from the viewer as a bookend to the film's start (figures 2 and 3). He opts not for a settled resting place but staggers towards the night horizon while hovering between life and death.

Figure 2. Still from Needle (1988)

Figure 3. Still from Needle (1988)

At this point it should be clear that such ambiguity reflects late socialist culture's emphasis on mobility and fluidity. One clue about the place of race in this mobility can be found in a 1989 Iskusstvo kino review of the film, which reads Moro as a figure beyond anti-establishment anger, instead masquerading as a romantic knight. The author, Marina Drozdova, then offers her own interpretation of Moro's blood type:

The question is whom will it occur to him to rise as (rise up) from his blood. Perhaps a neo-Jacobin, “panmongolist” (“though the name is savage . . .” for them “it caresses the ear”)—as Tsoi himself often appears on stage, though this would already be a different film.

Cut by the blade of his narrow eyes, “slanted and greedy,” into the exhausted expanse, where everyone was already exhausted and tired of everything long ago, perhaps Tsoi should have hacked away this given world?Footnote 55

Rare for its time, this foregrounding of Tsoi's race disconcertingly echoes turn-of-the-century “yellow peril” discourse, such as Vladimir Solov΄ev's poem “Panmongolism” (1894) and Aleksandr Blok's poem “Scythians” (1918), the sources of the lines quoted by Drozdova. Thus, perhaps what we find here is late socialism's racist subconscious: Tsoi as an Asian invader bent on destruction, which heightens his force as an actor.Footnote 56

While allowing for this possibility, I would like to propose that Drozdova's reading also points to an Imaginary East that rounds out Yurchak's Imaginary West: the figure not just of the west, but of Asia and Tsoi's Asianness as allowing for new imagined worlds unbound to any given place. The Solov΄ev and Blok poems have themselves been read as foregrounding east-west ambiguity, as well as Russia's long and problematic identification with Asia—Russia as, in Leah Feldman's words, “both and neither Asian nor European.”Footnote 57 Associating Tsoi with Blok's Scythians—his recasting of the Bolsheviks as Asians poised to assault the west—arguably ennobles rather than demeans through the figure of Asian revolutionary, of Asian neo-Jacobin. Indeed, this association resonates with the early Soviet state's efforts to foment world revolution via Asia.Footnote 58 In any case, Drozdova's point here is not to pigeonhole or stereotype Tsoi: she also connects his muted heroism to French existentialism and dandyism, and also to what she calls a global postpunk movement that has belatedly arrived in the Soviet Union from the west—postpunk defined by image-based free play (igra vo chto ugodno), unconcerned with the concrete rules torn down by punk. Thus, what we see in the article is an emphasis on Tsoi's Asianness—for Drozdova, a source of revolutionary energy, an apocalyptic clearing away of the old—but only as part of a larger picture of cultural circulation across east and west. In response to Needle's conclusion, she asks, “But where is he heading? To that America where he will never be? (And even if that America exists, does its force of attraction lie in its geographic reality?)”Footnote 59 Drozdova here illustrates perfectly Yurchak's Imaginary West: at the film's end, Tsoi traverses a deterritorialized imaginative space, a move accentuated by his association with an iconoclastic, Imaginary East. His identity emerges from the articulation of multiple associations and histories, some of which are discernibly Asian, but which together unsettle the constative meanings attached to racial phenotype or passport nationality.

Another virtue of Drozdova's reading is that, via postpunk, it offers a bridge between late socialism and a dynamic body of western critical theory that also emerged in the 1970s and 80s, namely Birmingham School cultural studies. As noted above, the postpunk link is apt—discernible in the influence on Tsoi of bands like Joy Division and The Cure—and Tsoi himself forged east-west networks for what might be described as a postpunk international. Most notably and brilliantly, soon after the January 1990 screening of Needle at the Sundance Film Festival, he and Nugmanov met with the Talking Heads’ David Byrne to plan a collaborative film project set in a post-apocalyptic Leningrad—starring and featuring the music of Tsoi; Byrne both acting and co-producing the soundtrack; and the screenplay co-written by cyberpunk founder William Gibson, who hailed Tsoi as “a half-Korean, half-Russian Bruce Lee, a real master of martial arts, unbelievably attractive,” and claimed that Kino's music inspired parts of his 2003 novel Pattern Recognition.Footnote 60 Birmingham scholarship highlights precisely such unexpected linkages—the circulation of music, gestures, and clothing—and adds a radical political horizon by considering these in relation to race, class, and gender inequality. For instance, Dick Hebdige's seminal Subcultures: The Meaning of Style (1979) shows how British punks from the white working class drew from reggae, which was brought to the UK by Black immigrants from the West Indies. Hebdige thus uses punk music and style to articulate together race and class, which in turn leads him to find in subculture forms the expression of “a fundamental tension between those in power and those condemned to subordinate positions and second-class lives.”Footnote 61 In punk, this tension is expressed through a tangible alienation that “gave itself up to the cameras in ‘blankness,’ the removal of expression . . . the refusal to speak and be positioned”—all qualities that could readily be ascribed to Tsoi.Footnote 62 Such attempts to recode class can be seen as part of a broader effort to arrive at flexible notions of identity: to cite one influential example, Stuart Hall's 1989 conceptualization of “new ethnicities” that eschew singular, essentialist notions of Blackness, Black experience, or Black activism (comparable to the reified nationalities established by Soviet policy) in favor of a “politics of ethnicity predicated on difference and diversity.” For Hall, cultural representation offers a canvas for negotiating this difference within difference by bringing into focus minority experience as diaspora experience, “and the consequences which this carries for the process of unsettling, recombination, hybridization and ‘cut-and-mix’—in short the process of cultural ‘diaspora-ization’ (to coin an ugly term).” The result of this process is a foregrounding of the margins and peripheries of each group—as well as the ways in which “racial differences do not constitute all of us”—in order to bolster cross-group alliances and the formation of Gramscian counter-hegemonic blocs.Footnote 63

Through his use of reggae beats in the song “Boshetunmai” but more broadly in the difficulty of applying fixed racial or national categories to him, Tsoi shows that it is possible to extend such theories to late socialism: to speak of “new nationalities” alongside “new ethnicities,” Soviet deterritorialization alongside western diaspora-ization. This pairing usefully grants Yurchak's account of late socialism much-needed political teeth: while Yurchak describes late-socialist culture as either felicitous or infelicitous in its performance of authoritative discourses, Hall forces us to parse through the political effects of this culture. Does Drozdova's reading of Tsoi advance cross-group alliances and counter-hegemonic blocs? Yes, in that it unsettles national and racial boundaries in ways that shockingly foreground minority agency. What about the appropriations of Blackness in Assa? Probably not. The film's Third Worldist undertones are compromised by its extension, even if unintended, of a long history of subjection: in this case, the minstrel tradition of whites performing as Blacks, from the perspective of which Assa's minority stiob seems not simply offensive but passé.Footnote 64

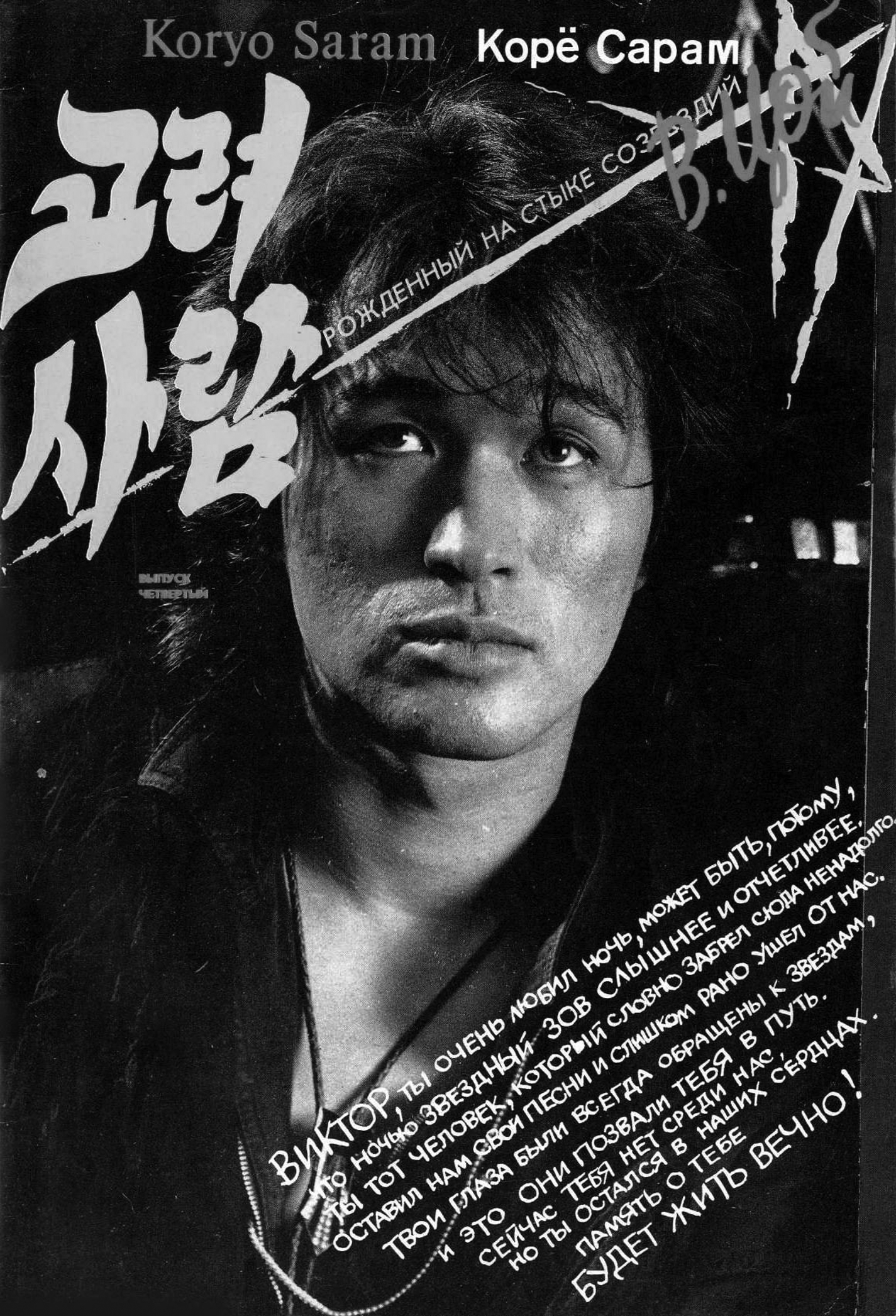

The combined perspectives of Yurchak and Hall also make it possible to better grasp the foreclosure of possibility after the passing of late socialism, as evident in what can be described as the post-Soviet territorialization of Tsoi's race and nationality.Footnote 65 For example, a journal produced by Russian Koreans in St. Petersburg devoted an entire 1992 issue to Tsoi (figure 4), providing details about his background, such as the Chinese character for his surname (Choe, in English typically rendered as Choi) and his ancestral homeland on the Korean peninsula.Footnote 66 It also published for the first time a family photo from the sixtieth birthday of Tsoi's ex-NKVD grandfather in Kyzyl-Orda, Kazakhstan (figure 5, an awkwardly adolescent Viktor stands in the third row, second from left); and republished individual reminiscences, including one by Nugmanov claiming that, as a Kazakh, he understood Tsoi through their shared Asian blood and that, in Tsoi's final years, “a new side of his nature, his blood” was opening, prompted by a 1990 visit to Japan.Footnote 67 Whether or not Tsoi indeed felt this way, such essentialist readings marked a turn from deterritorialization in ways evocative of one of the more rigid components of Soviet nationalities policy: the official enshrinement of national heroes and forebears.Footnote 68 Interestingly, however, such readings were not limited to the former Soviet Union: in South Korea, Tsoi first became popular among student activists in the early 1990s, both as an anti-authority figure and a beacon of socialism.Footnote 69 Among them was the prominent musician Yoon Do-hyun, who in 1999 released an album entitled “Korean Rock Recalling” (Han'guk rock tashi purŭgi), a search for the roots of Korean rock. Along with remakes of South Korean classics, Yoon included his Korean-language version of “Blood Type,” which he implicitly reinscribed as being about Korean blood. Concluding with a cry for freedom and peace, Yoon's version is a melodramatic rendering of the original, for example, translating the refrain “Wish me luck in the fight, wish me that I won't get stuck in this ground” as, “At the fight protect my soul, here on the cold land I will bury my blood.” Thus, in place of mobility, Yoon's version emphasizes rootedness: blood-soaked territory in place of deterritorialization. All of this speaks to the paradoxical rise, in both the former socialist world and beyond, of ethno-nationalism amid the 1990s triumph of neoliberal globalization.Footnote 70

Figure 4. Koryo Saram journal cover (1992)

Figure 5. Tsoi family photo, from Koryo Saram (1992)

In more recent years, the territorialization of Tsoi has taken the form of the Russian state monumentalizing him through statues, squares, and other such tributes.Footnote 71 More unnerving, though, are instances of deterritorialized nationality gone awry: the playful unsettling of racial and national boundaries being pressed into the service of militant nationalism. For instance, uncannily echoing Drozdova's reading of Tsoi as westward invader, at a June 2022 St. Petersburg exhibit celebrating Tsoi's sixtieth birthday, the artist Aleksei Sergienko unveiled a portrait of an armed Tsoi in military uniform, a tri-color “Z” emblazoned on his sleeve. Staring out against a backdrop of presumably Ukrainian urban ruins, his impassive face is conspicuously pale, as though to de-accentuate his Asianness. Here we see the racial fluidity and decontextualized overidentification with official policies that I have associated with deterritorialized nationality, but in this case unambiguously aligned with state interests, as the artist made clear in interviews.Footnote 72 Co-opted deterritorialization has also figured prominently in state-sponsored social media misinformation: for instance, the now-familiar phenomenon of Russian internet trolling, in which individual posters identify with multiple, conflicting political positions in order to heighten confusion and cynicism.Footnote 73 Journalists have covered how, during the 2016 US election cycle, the St. Petersburg troll factory known as the Internet Research Agency created popular social media accounts such as “Blacktivist” and “Stop All Invaders,” performing the roles of both Black Lives Matters activists and white nationalists.Footnote 74 For the Russian trolls, all the direct or indirect products of late socialism, the constative dimension of American racial discourse—which, in its crudest, most reductive form, casts one simply as either racist or anti-racist—was irrelevant. What mattered was the trolls’ ability to repeat the rituals and forms of American discussions on race, for instance the clash of slogans like “What kind of protest has ever been acceptable?” and “Sharia law should not even be debatable,” as well as images of violent confrontations between police and demonstrators. The trolls’ performance particularly of African American roles echoed the instances of minority stiob found in Assa. Again we find decontextualized overidentification with Blackness, but now harnessed for geopolitical ends—an attempt to undermine the US by ironically performing the roles established by American racial discourse.Footnote 75 Deterritorialization here works to negate this discourse in ways that reinforce the very kinds of binaries (east versus west, race versus race) once so seamlessly confounded by the last Soviet generation.

In contrast to such examples of stiob gone cynically awry, the Tsoi of late socialism shows how deterritorialization can breathe new life into authoritative discourses by revealing within them unanticipated meanings and positive values—for instance, the hybrid and syncretic minority representations, resonant with western critical race theory, that were possible during perestroika. Deterritorialization also reveals the radical, unrealized internationalisms surrounding Tsoi prior to his death—the (compromised) Third Worldism of Assa, the Imaginary East and West of Needle, as well as the postpunk collaborations that never came to be—all of which offer Soviet-inflected counterpoints to actually existing globalization and its attendant ethno-nationalisms. Against the cold wars and culture wars that are currently ascendant, a grasp of deterritorialized nationality in its positive forms keeps alive the utopian, cross-racial possibilities of that time—a key component of Tsoi's enduring allure.