Introduction

The turnip played a central role in the farming of Great Britain from the late eighteenth century right through to the middle years of the twentieth.Footnote 1 While agricultural historians might dispute the chronology of its introduction, by the middle years of the nineteenth century, it was firmly established in crop rotations.Footnote 2 Many aspects of its cultivation, allowing for differences in climate and soil types, were broadly similar across the country. However, there is a stark difference between the careful and detailed descriptions of the practice of turnip hoeing in memoirs of farm life in northeast Scotland and relative silence elsewhere.Footnote 3 On further investigation, out of what might seem to external observers, the relatively mundane practice of removing weeds and singling plants by the use of the hoe grew an elaborate array of competitive hoeing matches in Aberdeenshire in particular.Footnote 4 In these, hoers were allocated a limited time to hoe a set length of turnip drills, being judged on both speed and accuracy. Prizes were awarded and matches attracted large numbers of both competitors and spectators, building to a peak in the 1930s. Contrasting these with the limited traces of such events in the rest of Scotland, and to a limited extent, in England and Wales, is at the core of this article.

In his investigation of changing senses of place in rural England, Keith Snell uses the traces left by one taken-for-granted practice, the memorial inscriptions carved on gravestones, to track how people chose to record geographical attachment.Footnote 5 An exploration of practices of religious governance, ones which were often consequential for the rural poor, has shown how different they were in eighteenth-century England and Scotland. In the former, practices varied considerably from parish to parish, forms of record keeping, and participants being largely governed by local custom and tradition.Footnote 6 In Scotland, by contrast, there was much more consistency, with adherence to procedures laid down centrally producing detailed records. Relating such practices to broader societal logics indicates what has been termed a culture of personal accountability in England, manifested in trust in the personal qualities of office-holders, in contrast to systemic accountability in Scotland, in which trust lay in the operation of procedures that could be, and were, tightly monitored. It is this focus on taken-for-granted practices that animates this article.

Practices that are seen by participants as routine and ‘natural’ can often generate broader senses of culture and identity. For example, writers on religion have suggested that it is participation in ritual practices, such as acts of collective worship, that foster belief.Footnote 7 While those practices might have originated in belief as theorised by the theologically adept, for the ‘averagely faithful’ arcane disputes about the origins of the practices they engage in are not germane. Rather, it is the practices they engage in with others that foster not only belief but also a sense of identity. Examining such taken-for-granted practices, which are often neglected by accounts that focus on more abstract questions, can provide insights into broader cultural norms that might influence attitudes in other spheres of activity.

There are a number of challenges in exploring practices.Footnote 8 One is the availability of evidence. Oral history has been found to be a valuable way of recovering routine practices, especially those associated with work.Footnote 9 However, the practices explored here lay beyond the reach of memory, except as recorded in the memoirs already noted. The widespread digitisation of local newspapers offers us one valuable source of evidence. One is struck by the detail of recording of rural affairs, with detailed commentaries on the status of crops a feature of many local newspapers. Some newspapers carried reports of practices far outside their home county. This was particularly true of the Aberdeen Journal and its successor (from 1923) the Aberdeen Press and Journal, which often reported on farming matters outside Aberdeenshire. The availability of such newspapers for searching is conditioned by those which have been digitised, with better coverage for the east and south of Scotland. There are other limitations on such sources, as will be discussed in more detail later, but they do offer us a potential way in. The other problem with taken-for-granted practices is simply their ‘obvious’ nature. This means that they tend to fade into the background and we need some way of, as it were, ‘making them strange’. It is here that contrastive forms of investigation, such as those with the ability to search newspaper reports across a wide range of settings, are valuable. It will be seen below that there appears, from the evidence of newspaper reports, to be a stark difference between practices in Scotland and England. However, as Barry Reay reminds us, there were many ‘Rural Englands’.Footnote 10 While some pointers are presented in this article for further research, the available evidence is skewed towards one region of England, the southwest. Accordingly, while some English examples are given by way of illustration, the major contrast essayed here is between the northeast of Scotland, particularly Aberdeenshire, and the rest of Scotland.

The article begins by outlining some of the material dimensions of turnip cultivation, with a focus on the practices that it entailed. This section does not aspire to be a comprehensive treatment; its purpose is to provide context for the main focus on competitive hoeing matches. A quantitative examination of newspaper reports, with suitable caveats, indicates a significant contrast between, firstly, Scotland and England and, secondly, within Scotland between Aberdeenshire and much of the rest of the country. The contrast is about the cultural meanings attached to the cultivation of turnips, something that is particularly visible in the prevalence of competitive turnip hoeing matches in Aberdeenshire in the years between 1850 and 1940. The development of such matches is explored in some detail, showing the increasing size and organisational complexity of such matches, with focus on the prevalence of Hoeing Associations and champion hoers in the 1930s. Such organisational forms are contrasted with the rather limited examples outside the broader northeast, where a more ‘top-down’ approach, similar to that to be found in English examples, seemed to be at work. The article concludes by setting these contrasting practices in their broader social and cultural contexts. While some differences in material factors are pointed to, the main conclusion is that different cultural consequences could flow from practices. The value of attending to taken-for-granted practices and what they reveal about broader social and cultural factors is stressed.

Cultivating the turnip

Turnips were an important crop in the farming systems of the period for two reasons.Footnote 11 One was that they were regarded as a ‘cleaning crop’. The traditional practice was to allow land to rest fallow before being cultivated for a grain crop. Fallowing did not necessarily mean that land was not cultivated to remove weeds and restore fertility but it was an unproductive part of rotations. Growing turnips as a break crop between cereals meant that land was still productive. The cultivation needed to make a seedbed for turnips and, more importantly, the weeding that was necessary to make the most of the crop was an ideal preparation for a grain crop the following year. The second was that they increased the carrying capacity of the land in terms of livestock. That might be sheep folded on the turnips in the fields, as was often the practice in the eastern counties of England in particular, or cattle fed indoors over the winter months. In both cases, turnips enabled the production of valuable manure, either dropped by sheep as they grazed on turnips in the field or mixed with straw from indoor-housed cattle.Footnote 12

Initially, turnip seed had been sown broadcast on land ploughed and harrowed to produce a seedbed. Over the course of the eighteenth century, farmers in Scotland innovated in ways that increased the productivity of the turnip crop in two ways. One was that rather than sowing turnip seed across a wide area, they earthed up the soil into ridges termed ‘drills’. As a report from the Borders parish of Mordington recorded for 1795

Though they are sometimes sown in what is called broad-cast, that is on ridges made up in the same manner as those on which barley, oats, or any other grain are commonly sown; yet they are more frequently raised on drills, from 24 to 30 inches wide. This latter method is preferred, on account of its giving an opportunity for horse hoeing, and thus occasioning less manual labour, and consequently less expence in thinning and cleaning them.Footnote 13

An obituary in the Caledonian Mercury for 1822 records that one James McDougall ‘was the first ploughman in Scotland that drew a straight turnip drill with a two horse plough, without a driver’.Footnote 14 His employer, the noted agriculturalist William Dawson of Frogden, had undertaken an apprenticeship in Norfolk before returning to put what he had learned into practice in Scotland. The creation of a ploughed drill must have occurred at some point in the 1760s, a time of the rapid take off of new farming methods in Scotland. Sowing turnips on drills also required the development of a means of sowing seed in a straight line. Also known as drills, these implements were the occasion of much innovation in Scotland. For example, in 1802, the Caledonian Mercury reported on a meeting attended by upwards of 500 ‘gentlemen and agricultural amateurs’ hosted on an annual basis by Mr Sitwell of Barmoor Castle. Amongst other demonstrations, they witnessed ‘a turnip drill, invented by Mr JOSEPH LOWERY, steward to JOHN FORDYCE, Esq. of Ayton’.Footnote 15 Such implements made it possible to sow turnip seed in a continuous line. However, the plants needed to be singled so that they had room to grow. The careful preparation of the ground also made for an ideal growing medium for weeds, so there was a need for weeding.

Kames, in his Gentleman Farmer of 1776, argued for the value of hand weeding of the turnip crop by women and children.Footnote 16 However, by the nineteenth-century, weeding and singling were done by use of the hoe in Scotland, in contrast to some parts of England, where it was still done by women and children on hands and knees.Footnote 17 It was a labour-intensive process. The demands of other crops could mean that the regular farm workforce needed to be augmented. An important observation is that employment practices differed across Scotland. In the more intensive arable districts of the southeast, the workforce was largely composed of farm labourers, living in cottages and hired by the day or the week. By contrast, in the northeast, the majority of the workforce were farm servants, hired by the year and living on the farm. There was a distinction here between the areas where such servants lived in bothies, where they prepared their own food, and those who lived in a chaumer, a room in the farm buildings but took their meals in the farmhouse kitchen. Bothies were more prevalent in Angus, but servants in the chaumer were dominant in the northeast, especially in Aberdeenshire. Farm servants were young, male, and single. They would tend to move on when married, many to small farms or crofts, but some to be farm labourers, living in cottar houses.Footnote 18 These distinctions will be important when we consider the cultural impact of turnip hoeing. However, while turnip hoeing was an important task for them, they would need to be supplemented. Such supplements might come from local tradesmen, who would often be skilled hoers from raising the crop on their own small land holdings. However, women and children could also be mobilised. Thus, in Aberdeenshire, the Garioch Farmers’ Club resolved in 1813 to offer premiums based on performance in competitive hoeing matches, ‘being very sensible of the utility of having the women practised to the hoeing of turnips’.Footnote 19 (The initiative, it appeared, met with success, for two years later it applied to outdoor work by women in general). The gendered nature of turnip hoeing matches is another consideration to which we will return.

Aberdeenshire hoeing matches: trials of skill

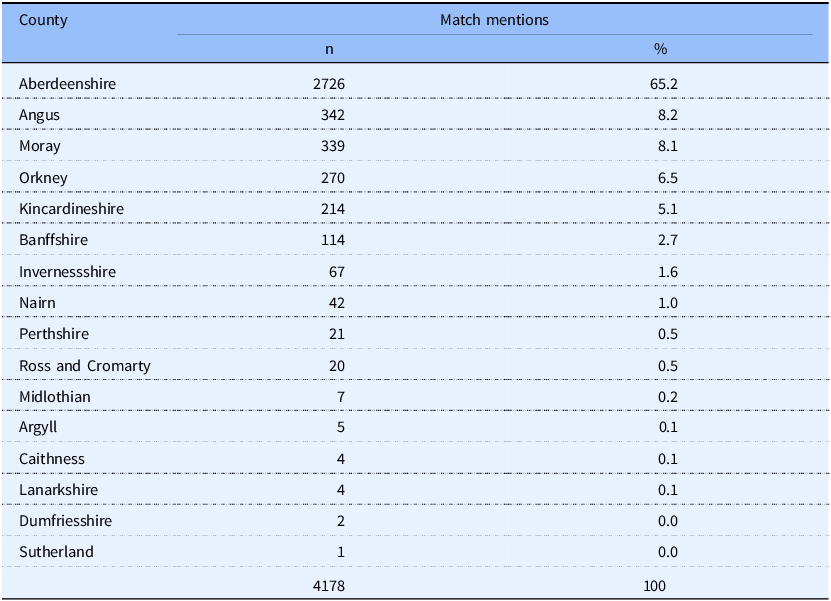

Table 1 shows the results of searches on the British Newspaper Archive. Before exploring these results, some caveats are in order.

Table 1. Newspaper reports by country 1750–1999: British Newspaper Archive

These figures are the result of searches using the terms ‘hoeing match’ and ‘turnip hoeing’ against the whole body of material as of February 2024. While this covered publications from 1750 to 1999, the overwhelming majority of material was from the period 1850 to 1949 (96 per cent for hoeing matches, 91 per cent for turnip hoeing). The searches were made using the ‘exact match’ function and inspection indicated that the optical character recognition was generally accurate. Any spurious results would be marginal. The use of the term ‘turnip hoeing’ was designed to pick up mentions from England and Wales that might not be picked up by the more specific term, and it can be seen that this gave more results, although still indicating greater proportional reporting in Scottish newspapers. The overall figures therefore give a good picture of newspaper reports, but it has to be acknowledged that these are reports and so might reflect editorial judgments rather than an ‘accurate’ picture of practices on the ground. It also has to be noted that the archive allocates reports on the basis of where the newspaper was published, and so might not be an accurate picture of county practices. Furthermore, the search is a measure of reports, whereas one report might mention several events under one heading. These points can be illustrated by a report in the Banffshire Journal for August 1861.Footnote 20

The report began with the observation that ‘an immense number of hoeing matches have lately been held all over the country’. It then listed the number of competitors and the first prizewinner for thirty events, all of them in the neighbouring county of Aberdeenshire. It is highly possible, therefore, that the counts given above tend if anything to underestimate the number of hoeing matches that took place, necessitating closer inspection of the results. The figures do, however, provide us with a useful starting point. Looking at Scotland in more detail, we can see confirmation of the dominance of Aberdeenshire when it comes to reports of hoeing matches.

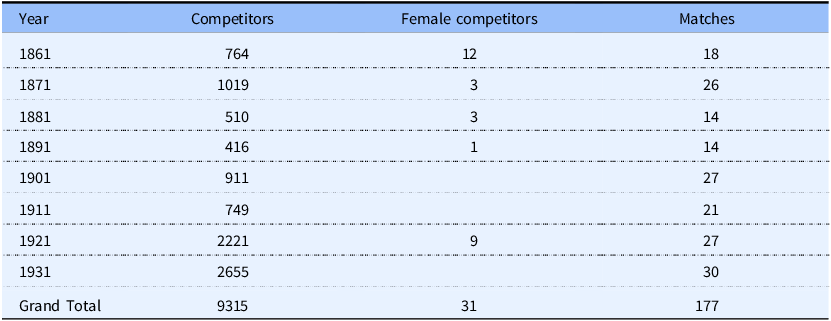

The figures in Table 2 are for counties with any mentions. Outside Aberdeenshire, the mentions are concentrated in the lowland districts of eastern Scotland north of the Tay. Given the clear dominance of Aberdeenshire in the results for hoeing matches, this section explores reports for that county in more depth, before looking at some examples further afield. Given the sheer volume of reports for Aberdeenshire, it was necessary to carry out a more focused analysis. Accordingly, the reports for each decennial census period starting in 1861 were inspected as this allowed for further matching to the census returns. Not only could the number of matches and competitors thus be ascertained but also some detail on participants could be traced in census returns.

Table 2. Mentions of hoeing matches in Scotland 1840–1999: British Newspaper Archive

Not all reports gave number of competitors; in these cases, the numbers of prizewinners (which were always given by name) were used. This means that the figures, especially for the earlier periods, are likely to be an underestimate. In particular, the number of female participants is almost never given and so the figures are for prizewinners. (In 1891, Mrs Middleton, wife of the local blacksmith, ‘gained a special prize as the only woman hoer’ in a match at Wardhouse.Footnote 21 This was the only mention of the number of women at matches). Despite this, what one can observe is the substantial number of competitors, a number that grew through the period.

Emergence and development

The first report of a competitive turnip hoeing match in Aberdeenshire came in August 1856 when thirty competitors assembled on a farm in the parish of Methlick.Footnote 22 Once started, the innovation spread rapidly. In 1860, the Peterhead newspaper reported that ‘turnips having shown a most luxuriant briard this season, hoeing matches have been in the inland districts, of almost daily occurrence’, something that occasioned an emulation nearer the coast.Footnote 23 One source for the origins of the practice might have been indicated in the report in the Banffshire Journal noted above. A match had been ‘kindly got up by a number of the neighbours and friends of Mr J. Fowlie, Brucehill, in order to further his hoeing, which had fallen behind, in consequence of severe family affliction’.Footnote 24 Between eighty and ninety hoers turned up in this act of collective self-help. Other examples of what in 1921 was termed a ‘love darg’ featured in the reports (darg being the dialect term for ‘to dig’, by extension coming to mean any routine task).Footnote 25 In that case, ‘the love darg was promoted by neighbouring farmers to help on the work of the croft’.Footnote 26 In other cases, farmers sponsored annual matches on their land, thus getting hoeing done in return for a small outlay on prizes and refreshments for the competitors. Thus, in 1871, ‘Mr Alexander Mackie, Hill of Rora, held his annual hoeing match the evening of Tuesday the 4th inst., when between fifty and sixty hoes were set agoing by many crack hands’.Footnote 27

Whatever the origins, as the century wore on, hoeing matches became more organised, with advance notice being given in the advertising columns of local newspapers. It is possible that ploughing matches supplied a template for organising these events. The first mention of such a match in Aberdeenshire came in 1796 when ten ploughs competed near Fraserburgh.Footnote 28 Such matches saw the drawing of lots to allocate parts of the field to ploughmen and the winning of silver medals. From the beginning of the nineteenth century, such medals were sponsored by the Highland Society, something which did not happen with hoeing matches until much later (the first mention of such sponsorship was in 1914).Footnote 29 Many of the associations that grew up to organise hoeing matches would over time become combined hoeing and ploughing associations. One sample advertisement from 1909 from an association solely concerned with hoeing can act as a guide to how such matches took place that we can then unpack:

THE BRUCKLAY HOEING ASSOCIATION will hold their Annual Match at Mr JOHN PANTON’S, Overhill, New Pitsligo, on WEDNESDAY, 7th July, at 7 o’clock p.m. Champions 1s, Locals 6d, Boys 3d. Dimensions, 7 inches. Medals and Money Prizes will be given.Footnote 30

A starting point is that these were evening occasions, so after work. That restricted the time available for the competition and so the amount of work that could be expected. At the first Muchalls hoeing match in 1864, competitors were allowed an hour and twenty minutes to hoe two hundred yards.Footnote 31 Competitors paid an entrance fee, and the drills were drawn by lot. While organisers might seek to obtain what was literally a ‘level playing field’, vagaries of soil condition, plant sowing, and growth and the weather could all interfere. At Tyrie, in 1913, some competitors ‘were rather handicapped by being placed, owing to the large tum-out, on a rather stony part of the field’.Footnote 32 Likewise, at New Deer in 1911 ‘heavy ruin prevailed throughout the day, and although clearing a little towards evening, the field was in a rather sodden condition, and greatly handicapped the competitors’.Footnote 33 Competitors were allocated a number by a bookkeeper so that their performance was judged against the number of their drill rather than by name. A timekeeper gave a signal to start and finish. Competitors brought their own hoes, which were designed to produce the gaps between plants laid down. Judges, often expert hoers from a previous generation, measured the distance between plants and frowned upon any handling of the plants. This was because transplanted turnips would never grow properly.Footnote 34 The emphasis was on both speed and accuracy, although judges often disagreed about the trade-off between the consistency of plant spacing and the size of the plants left. As one judge explained when commenting on the work demonstrated by an expert hoer for the Finzean Junior Agricultural Club, ‘too many judges paid too much attention to the regularity of the turnips, whether the plant was large or small, whereas he would prefer to see the large plants left, even although they were not quite regular’.

He also impressed on competitors the value of taking the whole side of the drill with one stroke of the hoe so that as little time possible was spent on the drill, giving more time for selection and singling of turnips. He also advised them to keep the drill well up, and round well, with the plants as near the centre of the drill possible, pointing out how neatly Mr England had dressed his drill, how well-balanced and how alike both his drills were.Footnote 35

Prizes and competitors

The early matches simply noted the places obtained but over time an increasing number of prizes were awarded. These were partly funded by entrance fees, partly by social functions to raise funds, and partly by donations from local businesses. Prizes could be quite modest in the earlier days. Thus at St Cyrus in 1881, ‘a number of the successful competitors were presented with prizes, in the shape of money, tobacco, tea, &c. subscribed for by a number of friends’. In the same year at Cocklaw, the prizes were a whip, a pair of braces, a nightcap, and a pocket knife.Footnote 36 However, the same year saw what seems to have been the first match featuring silver medals as prizes. This was at a match at Auchindoun, in the neighbouring county of Banffshire (but a match reported in the Aberdeenshire press). Here, ‘Charles Cantlie, Esq., gave two silver medals, one for the best male hoer, and the other for the best female hoer’. Such medals became keenly contested and emphasis on them grew. In Balthangie, in 1911, ‘the management, with their usual enterprise, offered tempting inducements, in the form of handsome money prizes, together with silver medals for the premier awards in each section. The coveted trophy, however, was the massive challenge cup given for the best hoed drill on the field’.Footnote 37

Organisers were also inventive in finding other ways of awarding prizes. The 1881 Drumoak match featured prizes for the hoer with the longest service, the oldest and youngest hoers, the hoer with the largest family, and the best drill hoed by a tradesman.Footnote 38 At the Auchindoun match, there was an award for the competitor who had walked furthest to the match (we will return to the winner below). As noted for Wardhouse, even when there wasn’t a specific class for women, women hoers could get a special prize. In 1901, there was a prize at the Ythan Wells match for the best-looking hoer and at Longside for the hoer most recently married.Footnote 39 What such prizes point to is the important social dimension of the matches, which frequently concluded with a dance in the loft of the farmer’s barn. At Rora in 1871, after a match attended by between fifty and sixty competitors, dancing continued well after midnight:

On the completion of the work, both workmen and spectators were abundantly supplied by Mrs Mackie with creature comforts. A musical instrument and musician having been procured dancing pretty much in the ram reel style was keep by those possessed of a superfluity of animal spirits till the “wee smaa hour ayont the twal”.Footnote 40

Match reports gave the names of prizewinners and where they were from. They also often gave occupations, especially if these were in trades. Such lists allow us to get a sense of the participants and further details can be gleaned by cross-referencing the census returns. For a match held in Methlick on 2 July 1861, occupational data are available for all twenty prizewinners (of sixty entrants).Footnote 41 The winner was John Anderson, a twenty-seven-year-old farmer’s son working on his father’s seventy-acre farm. There were another seven farmers’ sons hailing from farms ranging in size from seventeen to seventy-eight acres, with an average size of thirty-four acres. The biggest group was the eight farm servants, that is, men hired by the year and living in the farm buildings. There was also an overseer from a 500-acre farm, a definite outlier in this district of small farms. In addition, there was one farmer, working his mother’s twenty-acre croft at Backhill of Ards. The numbers were made up of three tradesmen: a flesher (butcher), a blacksmith, and a wright. The ages of these winners ranged from seventeen to thirty-five, with an average age of twenty-six. These details give us a sense of the milieu from which competitors were drawn, with the dominant group being a mixture of farmer’s sons from the small to medium-sized farms that characterised the area and the farm servants who worked on the larger farms, leavened with a sprinkling of tradesmen.

As noted above, it is difficult to assess the participation of women in these events, as only prizewinner details are given in the reports. While female prizewinners were always numerically marginal, their greater presence at mid-century events is perhaps a reflection of their activities in the fields. At this time, there were still women employed as outdoor farm servants, although their numbers were declining. At the Lonmay match in 1861, Mary Percival, aged eighteen, was living with her unmarried aunt, the dressmaker Isabella Webster, when she came third out of a field of fifty-five. Margaret Milne, who came seventeenth, is likely to have been the sixteen-year-old dairymaid on the forty-acre Roundhill farm in the parish. It has not been possible to trace Catherine Alexander, who came in fifteenth.Footnote 42 The numbers thereafter diminish, probably under the influence of notions of separate spheres of activity: men in the fields, women in the house. Certainly much later accounts of turnip hoeing stress the opportunity for men to swap bawdy gossip and jokes.Footnote 43 It was not until the stresses of war and the consequent shortage of labour that women were again considered as potential competitors. In 1916, William Watt, a prime mover in hoeing matches, wrote to the Aberdeen Journal in response to suggestions that a women’s category be added. ‘When we are hearing so much and reading much of the abilities and willingness of the women undertake certain kinds of farm labour’, he wrote, ‘this should be a favourable opportunity to make a start, and show their prowess’.Footnote 44 There was certainly a ladies’ category at the Fetterangus match that year and subsequent matches continued the practice. These were often the newer matches, with the recently formed Turriff Association putting on a match that attracted record numbers in 1924. It featured a ladies’ section with eight prizewinners. However, this renewed enthusiasm was not to last. Despite the newly formed Cluny association featuring a ladies’ class, which attracted six entries in 1937, participation remained overwhelmingly a male affair.Footnote 45

Growth and organisation

Hoeing matches started out as local affairs but, as they became more established, competitors came from further afield. To return to a match just over the border in Banffshire, when Peter Young won the prize for the hoer who had walked furthest to Auchindoun in 1881, he had travelled the seven or so miles from Aberlour. He was an eighteen-year-old farm servant.Footnote 46 Matches continued to grow in number and size, reaching a peak in 1924 when the match at Turriff drew not only 192 competitors but also some 600 spectators. Spectating was an active business as they followed the hoers up their drills. At Millbrex in 1907, there was ‘a good deal of excitement towards the finish as there were several running each other very close. The field was visited during the evening by a large number of onlookers, who showed great interest in the work’. Numbers of spectators were swelled as at Tyrie in 1912 ‘when it became known that such champions as Beaton of Nether Boyndlie, and Gordon of Middlemuir, New Deer, were amongst the competitors’. Such an observation points to the growing organisation of matches and the emergence of a new class of competitors, the ‘champions’.

The first formal association to be mentioned in a newspaper report was that at Muchalls in 1864. It had been ‘lately organised for the Promotion of Social Intercourse, as well as the Improvement of Agricultural Labour’, an interesting echo of the Mutual Improvement Societies that were a distinctive feature of Aberdeenshire rural life at mid-century.Footnote 47 Table 3 shows the figures for matches organised by associations that were recorded in each of the sample years. Despite the example of Muchalls, associations did not really take off until the twentieth century.

Table 3. Newspaper reports for Aberdeenshire hoeing matches 1861–1931: extracted from British Newspaper Archive

The associations grew out of local committees that organised matches and were a measure of the growing scale and popularity of hoeing competitions. They organised social events to raise money for the prize fund. One particularly active association was the Brucklay Hoeing Association and one of their social events is worthy of special mention. The Buchan area of Aberdeenshire is renowned as the premier source of traditional ballads in the country and its premier collector at the period was Gavin Greig (1856–1914). His massive collection with the Reverend J. B. Duncan extended to eight volumes and was part of considerable local pride in songs and writing couched in the Doric, the distinctive language of the northeast. In 1906, he gave a lecture on ‘Our Old Buchan Songs’ at a meeting at New Deer organised by the Brucklay Association. His lecture ‘dealt with the traditional minstrelsy of the district, analysing its characteristic features, and referring to the movement now on foot for collecting our old folk-songs’.Footnote 48 In an area also known for the songs written and sung about farm life collectively known as ‘bothy ballads’, this had considerable resonance.Footnote 49 Thus, a match organised by the Brucklay association was the occasion for a fifteen-verse poem to be published in the Buchan Observer and East Aberdeenshire Advertiser using the Doric to extol the virtues of prizewinners, judges, and host alike.

Twas a sicht when that army o’ men,

Mair than threescore and ten sturdy chiels,

A’ eident [industrious] and earnest, and bent to their wark,

Were spread far and wide owre the drills.Footnote 50

Inter-war triumph and decline

It was the inter-war years that were the high point of hoeing association matches, with new associations, such as at Turriff and Cluny being formed (Table 4). Associations were now often combined with hoeing and ploughing associations. With their dominance came the era of the champion hoer. As early as 1860, a report could refer to the ‘crack hoers of this district’, a formulation that was by the early twentieth century shortened to ‘cracks’: ‘Ninety-two competitors, including the pick of the local men as well as some noted cracks from a distance’ competed at the meeting of the Balthangie Ploughing and Hoeing Association at Monquhitter in 1904.Footnote 51 Early matches generally had two classes, men and boys, but by 1901, the Balthangie association was holding a champion class in addition to an ordinary (or local) and boys class.Footnote 52 Champion classes were open to those who had won first prize in the ordinary category and noted champions started to emerge. In 1912, James Beaton won the inaugural hoeing match of the Central Aberdeenshire Association. This body aimed to be what we might term the ‘cup final’ for hoers and it attracted champions from many of the local matches. As its chairman stated in 1922, ‘they had continued, he said, now for a number of years to draw the principal hoeing champions from all parts of the county. Being favourably situated in the centre, their match was considered the principal battle ground for the champions to meet and decide who was to be regarded as the year’s champion’.Footnote 53

Those who triumphed were regarded as local celebrities, attracting the sort of newspaper coverage later accorded to football stars. For example, the result of the 1912 contest was reported under the headline ‘the hoeing champion’ and under a photograph of the winner was the report that it was of

Mr James Beaton, Mains of Glack, who won the championship hoeing match which took place at Sunnyside, Wartle, in a field kindly granted by William Watt. Mr Beaton is an expert hoer. He won his first medal at Balthangie, Monquhitter, about nine years ago and has been three times champion there. His prizes include three silver cups and a gold medal at Millbrex. One of the cups was a challenge trophy which was secured by Mr Beaton twice in succession. He also won a cap at New Byth, a gold medal at Brucklay, and he also holds several silver medals awarded at various other places.Footnote 54

Something of the effort that this represented can be seen in the career of one outstanding champion, Robert England. Entering his first champions’ class in 1925, he competed in 85 matches between then and 1939, winning thirty-four first places. In his most successful year, 1931, he competed in ten matches with six first places. That represents about two matches a week, some at a considerable distance. The furthest from his farm at Bucharn near Banchory was Turriff, some forty-five miles away.Footnote 55 Given that he had his own farm to run after a number of years when he competed as a farm servant, and that these were evening matches, the sheer amount of work is remarkable.

The year 1931 turned out to be the high-water mark of the competitive hoeing match. Even before the external jolt of war, this could be seen in the declining numbers competing in the Central Aberdeenshire event. From 130 entrants in 1931, this declined to ninety in 1935 and fifty-four in 1936, after which reports ceased. There were two causes. One was internal to the dynamics of the competition. The Buchan Observer and East Aberdeenshire Advertiser, arguing that the hoeing match was ‘something of a dying institution’, put the blame on the emphasis on champions and their ability to attend more matches thanks to the increasing mobility afforded by motor transport. ‘But when deck-sweepers from afar off enter the lists it is as a damper for the local cracks’, the correspondent argued, suggesting some remedies.Footnote 56 However, against these were the longer-term trends in farming practice, specifically the replacement of the turnip by silage for feeding cattle. The shift was starting to be discussed in the early 1920s, although farming conservatism and the need for new infrastructure meant that it did not take off fully until after the Second World War.Footnote 57 By that stage, turnip hoeing was more a means of stimulating young farmer involvement than the fierce competition that it had been.

Further afield in Scotland

It was noted above that one limitation of the analysis of newspaper reports was that the county of publication did not necessarily correlate with events in that county. That was certainly the case for Lanarkshire and Midlothian, where all the reports were for other counties and reflected instead their place as the base for national newspapers like the Daily Record and the Scotsman, respectively. However, the reports for other counties do suggest some caution about the representativeness of the analysis. There were only two mentions of hoeing matches in Dumfriesshire, for example, but both referred to ‘annual’ matches. Both were in 1939 with no indication of how long either the match prompted by the Applegarth, Hutton, and Corrie Ploughing Association or that at Closeburn had been conducted. The latter match, however, was reported as having ‘been in abeyance for several years’. That forty-six people took part in the former match – twenty-six seniors, thirteen juniors, and seven ladies – does suggest some degree of permanence.

If we look at another county outside the cultural and material pull of Aberdeenshire and one with more mentions, Perthshire, we find that such mentions also point to matches with a longer pedigree. The first mention came in 1880, when a match, ‘the first ever held in the district’, was conducted in the Stormont area. Thirty-five competitors came forward. The first prize was taken by a woman, Mary McLaren of Mains of Fordie, and another woman, Jane Robertson, from the same farm, came fourth. Jane Roberston, in 1881, was the thirty-six-year-old wife of Daniel Robertson, farmer of the 200-acre Mains of Fordie and a member of the organising committee. The only Mary McLaren in the parish in 1881 was the forty-one-year-old wife of the ground officer and farmer of fifteen acres, Charles. These suggest a divergence from Aberdeenshire practice as being older women at a time when matches in Aberdeenshire were becoming male-dominated and the women who had competed previously appeared to have been younger. That the prizes were awarded by Sir A. M. Mackenzie, Bart, of Delvine does suggest a degree of elite sponsorship.

However, it is instructive to note that, on the evidence of newspaper reports, such matches did not ‘stick’. The next mention in a Perthshire newspaper did not come for over thirty years, and they were then reports of the Wartle championship match. It was not until the 1930s that a series of reports appeared about events in the county. As with Dumfriesshire, they indicated that matches had been occurring for longer. In 1931, the annual match at Glenlyon was held, an event which continued to be reported until 1938. In 1932, the ‘annual turnip hoeing match of the Mid Atholl and Tullymet Agricultural Association’ anticipated a field of between forty and fifty. These two matches were those with the most mention, although another event reported as ‘annual’ was held at Rannoch in 1933. In the last report, the Glenlyon event attracted twenty-seven hoes, the Mid Atholl thirty-eight. At the latter, there were five champions, ‘including one lady’, twenty-seven in the ‘Highland Society Medal ordinary class’, and six juveniles. While these are healthy numbers, they were clearly nothing like the numbers at Aberdeenshire events. It is perhaps also instructive that they were organised by Agricultural Associations; the Glenlyon event organised by the Glenlyon Ploughing and Agricultural Association. This is a further point of contrast with the Aberdeenshire experience, where associations dedicated to hoeing or at least equal with ploughing were the common form. Just as in Aberdeenshire, however, the coming of the Second World War marked a watershed, with the last report in 1952 being for an event organised, as Aberdeenshire events were, by a Junior Agricultural Club, in this case at Aberfeldy.

Conclusion: contrasting practices

What are we to make of the very different patterns of activity that a focus on the taken-for-granted practice of turnip hoeing has thrown up? The evidence points to the growth of a significant ecosystem of competitive hoeing matches in Aberdeenshire, one that peaked in the inter-war years and one that involved substantial numbers of both competitors and spectators. Outside of the counties linked to Aberdeenshire in northeast Scotland, both by similarities in farming and employment practices and in cultural norms, hoeing matches appear, on the evidence of newspaper reports, to have been less significant.

One key difference was the degree to which turnip hoeing matches were employer-led. It would be wrong to say that concerns about the availability of skilled labour were absent in Aberdeenshire. In the early years of the nineteenth century, the Garioch Farmers’ Club sought to increase the participation of women. However, the growth of competitive hoeing matches in the county was centred around the demonstration of skills. It was only in the early twentieth century that comments were encountered about the development of such skills as a contribution to agricultural productivity. At the 1922 meeting of the Central Aberdeenshire Hoeing Association, it was asserted that ‘all were agreed on the great advantage and profit in good, careful hoeing, and trusted the association would supported by farmers in their effort to secure a general improvement in hoeing’.Footnote 58 However, what the reports from elsewhere in Scotland suggest, echoing the evidence from England, is how much more prominent as a motive was this desire to enhance labouring skills through competition.

The format of hoeing matches suggests as much. The English matches were held during working hours, as was necessitated by the scale of the task set.Footnote 59 Matches usually began early in the morning so that they could continue for periods of around five hours. By contrast, the Aberdeenshire matches were evening affairs, which necessarily restricted the time that could be spent. Their focus was on the hoeing of a specified length of drill, with the aim being a mix of speed and accuracy. By contrast, the focus in the English matches was on area, with this generally being around a quarter of an acre. The focus was thus on emulating what an employer might be looking for, whereas, while the skill and accuracy exhibited by Aberdeenshire competitors could indeed aid farm productivity, it was secondary, as observers agreed, to the individual skill demonstrated. Thus the performance of the champion hoers tended to exhibit a polish that was pertinent to the demands of competition, not work.

The emphasis in the English matches on employment status was reinforced by the need for candidates to be sponsored by employers, at least in early iterations, and by the listing of who prizewinners were servants to. By contrast, in Aberdeenshire, the focus was on occupational status. Some were acknowledged as being farm servants, but others were farmers in their own right, farmers’ sons or tradesmen. Rather than an employer being given, the place of occupation was given. In addition, given the timing of matches, the social dimension was important. This was not only evident in reports of dances after the completion of competition but also in the social events, from concerts and dance to lectures on folk song, that characterised the associations that developed to further competitive hoeing. These were associations dedicated to the specific tasks of organising competitive matches, although over time they often coupled this with organisation of ploughing matches. By contrast, the English matches, as with several of those in the rest of Scotland, were organised by a range of organisations, usually agricultural societies, as an offshoot of their main activities.Footnote 60

These divergences were influenced by material factors in farming practice. In Aberdeenshire, turnips were grown for feeding cattle housed in byres in the winter. Turnips were pulled from the ground and carted back to the farm steading. The turnip was central to the farming of the county, a symbol of its success. By the same token, it was also a very visible symbol. Aberdeenshire was not a county with a tradition of nucleated village settlement. Rather it was a populated landscape of small farms, crofts, and cottar houses, meaning that the results of farming practice were widely visible. As the farmer Charlie Allan in his memoirs puts it of the years after the Second World War, when he participated in hoeing on his father’s farm, ‘a mistake beside the road was twenty times as bad as one in a shed. The great competition to be started and finished first with the very public jobs of hoeing turnips and harvesting were a universal passion’.Footnote 61

What this meant in Aberdeenshire was a focus on skill and the ability to work hard. Allan, again, places this in the context of the cultural norms of the farm servant: ‘First and last was the passionate devotion to the job and the mission to do it right’.Footnote 62 That mission could translate into the incredible effort to compete at turnip hoeing after a full day’s work. In turn, such norms have to be set in the context of the social structure of farming. As Carter explains, many farm servants were themselves the sons of small farmers or crofters, well used to hard farm work from an early age.Footnote 63 Many might expect to return to the farm in due course, and so there was no great social distance between them and the farmers’ sons against who they might compete. Tying this set of cultural norms together were the bothy ballads, songs created out of farming practice that focused on reputations, reputations that included the valorisation of hard work as a good in its own right.

One factor in the decline of hoeing matches might have been the gradual decline in the number of small farms, thus undermining the structural underpinning of this cultural complex. The aftermath of the First World War and the earlier imposition of death duties saw the breakup of many estates, enabling some farmers to purchase their land. In turn, this often extended to the engrossment of smaller holdings, thus removing the ability of many to envisage a future for themselves as farmers. It was not entirely beyond the bounds of possibility, as vividly illustrated in the memoirs of Mary Michie, who with her husband managed the move from croft to farm, but this was very much an exceptional journey.Footnote 64 By the years following the Second World War, the world of the farm servant was starting to disappear. While turnip hoeing matches did not vanish with it, they very much became an activity associated with young farmers’ clubs – clubs in which women played a more noticeable role.

As has been seen, participation in hoeing matches was very much a male preserve. While we lack firm evidence on the degree to which women participated in the routine hoeing of turnips on the farm, it seems clear from the evidence of newspaper reports that the matches themselves became increasingly male preserves. The jolt to this came with the demands of labour shortages in the First World War. The creation of a class for women at some matches during the war meant a degree of opening up in the inter-war years, but the evidence suggests that this was marginal in impact. An interesting contrast here is with the matches in other parts of Scotland, where the very limited evidence suggests greater participation by women. In discussing the decline of women as outdoor servants in Aberdeenshire, Carter notes that while in Perthshire women worked with horses, ‘the cultural prescription against women working with horses was absolute in the north-east’. He notes a decline in the number of women hired to carry out tasks such as turnip hoeing and concludes that ‘it is indubitable that fewer and fewer women did field work in the northeast’, something he attributes to a growing reluctance of girls to do work other than in harvest.

An examination of a routine farming practice, that of the hoeing of turnips, which often recedes into the background as a taken-for-granted aspect of crop cultivation, brings to sight considerable differences. It draws our attention to an otherwise neglected phenomenon, the competitive hoeing match, that was for a significant span of years a central social activity in certain parts of Britain. Revealing such activities in turn raises questions about why such matches were so prevalent in some areas and relatively absent elsewhere. Of course, there are limitations in the analysis presented. More work on practices in England where such matches did seem to exist would be very valuable. Newspaper reports are, of course, not the same thing as activities taking place, and it is entirely possible that detailed local studies using other sources might bring such activities to light. However, the thoroughness with which local newspapers covered farming matters in the period concerned does suggest that they are a valuable way of tracing practices. There could certainly be value in more work on the role of women in the weeding and singling of the turnip crop, just as it would be useful to look in more detail at the distribution of hand weeding as against hoeing.

However, what this article has demonstrated is the value of newspaper reports as enabled by digitisation in surfacing routine practices. It has also shown the value of contrastive explanation in exploring the differences thrown up by searches. While recognising the very different rural cultures existing within each country,Footnote 65 it is argued that more work contrasting practices on either side of the border could be very valuable.

Table 4. Aberdeenshire hoeing associations and champion classes: British Newspaper Archive

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the editor and reviewers for an exemplary reviewing process that was both speedy and constructive. Thanks also to John Orley for overcoming his initial incredulity about the nature of competitive hoeing matches and asking good questions.