In the winter of 1142, while the Byzantine Emperor John II Komnenos expressed his desire to visit Jerusalem, Fulk, King of Jerusalem, apologised to him, explaining his position in a letter, ‘The Kingdom is of very limited extent, nor does it afford sufficient food for so large a host. It could not sustain such an army without the risk of famine resulting from an utter dearth of the necessities of life’. Fulk expressed the city’s ability to receive only ten thousand of the emperor’s soldiersFootnote 1. Although this King had implied political reasons, his justifications did not go beyond what was right.

Indeed, food supplies were one of the great problems facing the Crusaders when they attacked the LevantFootnote 2. They were exposed to food crises during their invasion of the major cities, Antioch, Jerusalem, and TripoliFootnote 3, especially with the limited and irregular arrival of European supplies, which included wheat, wine, barley, meat, and cheeseFootnote 4. This forced the Crusaders to attack many local villages and plunder their cropsFootnote 5. They later became accustomed to fighting during the harvest season so as not to suffer from a shortage of food suppliesFootnote 6.

The provision of wheat was the essential requirement of the Franks when they settled in the Levant, but winds, storms, and pirate attacks were fierce obstacles to ships arriving with wheat from Byzantium, Cyprus, and SicilyFootnote 7. Also, the Italian cities’ efforts to bring in wheat and food supplies were feeble, at least until the mid-1130sFootnote 8. Claude Cahen, Jean Richard, and Joshua Prawer argued that the Franks in Antioch, Tripoli, Galilee, and Tiberias planted wheat in the outskirts and achieved self-sufficiencyFootnote 9. It seems that these historians were influenced by the accounts of European travellers who were dominated by religious sentiment and evangelical references, as those travellers attempted to draw an ideal picture of Frankish life in the East instead of understanding their political and societal realityFootnote 10.

This paper attempts to re-image the first fifty years of the Franks in the Levant, highlighting the importance of the Islamic countryside in securing their food supplies. Therefore, it relies on three vital pillars: first, highlighting the important crops cultivated in the Islamic countryside neighbouring the Franks and how much they benefited from them; secondly, studying the Frankish administration of the Islamic countryside villages, understanding the extent of its interaction with feudal influences; thirdly, reimagining the purpose of building Frankish castles and fortresses, beyond the stereotypical interpretation related to the military aspect.

Crops of the Islamic countryside and supplying the Crusader cities: Edessa and Antioch

Exploring the nutritional structure of the Crusader principalities, it is seen that they were in constant need of the Islamic countryside. For example, the county of Edessa, with its arms east and west of the Euphrates, was in constant need of grainFootnote 11. In the east of the Euphrates, it relied on the outskirts of Mosul and the fertile Harran countrysideFootnote 12, which was subjected to continuous pressure from the FranksFootnote 13. According to Matthew of Edessa, Edessa was meeting its need with wheat and barley from the fields of HarranFootnote 14, which was confirmed by William of Tyre, ‘Baldwin, Count of Edessa, hoped and believed that he would be able to secure ample provisions for his own citizens from the region lying beyond the Euphrates’. William continued, ‘The region in the vicinity of the river Euphrates produces most abundant crops. Taking advantage of this fact, our chiefs, ordered food supplies of every kind to be gathered there and transported by horses, camels, asses, and mules across the river. In this way, the towns and fortresses were supplied with a large quantity of food, sufficient for a long time. Special attention was devoted to provisioning the city of Edessa, even to an overabundance’ Footnote 15 .

At the same time, the Franks of Edessa reached the outskirts of Aleppo, west of the Euphrates. They took the castles of Aʿzāz, Tell Bāshir, Aintab, and Marash as bases to advance on the northern and eastern borders of AleppoFootnote 16. According to Arabic sources, the northern regions of Aleppo were famous for cotton, wheat, and other types of grains, while its western regions were planted with grains, olives, and fruits and the production of oil and raisinsFootnote 17.

According to Ibn al-ʿAdīm, wheat was the most important of these crops, as Aleppo had warehouses to sell it, in addition to hay, which was necessary for animal fodderFootnote 18. In addition to wheat, the countryside of Tell Bāshir was cultivated with cotton and milletFootnote 19. These crops were so important that their price was estimated in 1124 at one hundred thousand dinarsFootnote 20. William of Tyre added to Tell Bāshir’s food materials, ‘wine and oil’ Footnote 21 , making it a rich city compared to the rest of the dependencies of Edessa east of the Euphrates, which sometimes suffered from destitutionFootnote 22. This encouraged the Counts of Edessa to reside inside Tell Bāshir, not EdessaFootnote 23.

The Franks strategically used Tell Bāshir’s castle to monitor the fields of northern Aleppo. If the harvest season came and they could not provide food, they plundered the crops. For instance, in 1120, Jocelin I took advantage of the Muslim villagers’ reassurance over their truce with the Franks of Antioch, so he collected their crops and animalsFootnote 24. In fact, he utilised his attacks to force the inhabitants of Aleppo to conclude a suitable agreement that would guarantee him a share of their crops, which was achieved in April 1126, when he was granted half the production of the fields extending between Aʿzāz Citadel and AleppoFootnote 25.

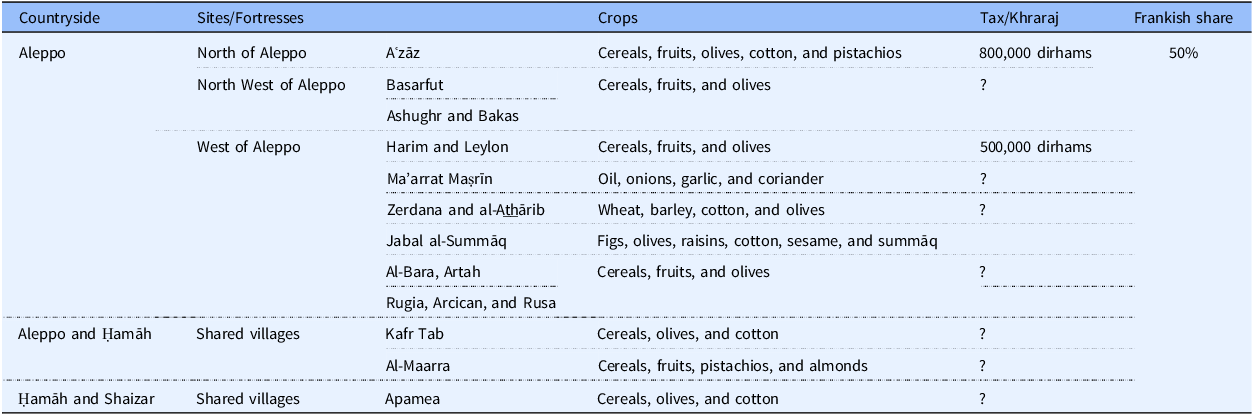

Thus, the castles west of the Euphrates were a logistical necessity for the Franks of Edessa to secure a share of food suppliesFootnote 26. Therefore, their loss of Edessa in 1144, in exchange for the survival of these castles, was merely a moral loss. Realising this, Nur ad-Dīn Mahmoud devoted his effort to annexing these castles. He was certain that this would cut off the Franks’ hope of reaching the fields of Aleppo, on the one hand, and would secure the trade line extending between Mosul and Aleppo, on the otherFootnote 27, so he seized Aʿzāz in July 1150Footnote 28and Tell Bāshir on July 18, 1151Footnote 29 (Table 1).

As for Antioch, its population was approximately one hundred thousandFootnote 31. Despite the agricultural activity around Jableh and LatakiaFootnote 32, Aleppo was the most important for AntiochFootnote 33. The villages between Antioch and Aleppo were famous for wheat, barley, olives, and fruits, according to a witness who visited the region before the arrival of the Franks and noted: ‘The distance between Aleppo and Antioch was a fertile land, cultivated with wheat, barley and olives. Its villages were connected, its gardens were blooming, and its water was plentiful’Footnote 34. The fields of Ḥamāh and Shaizar also contained the same crops according to some studies that concluded that the Levant in the years of the Franks’ arrival was abundant with rainwater and full of cropsFootnote 35. Cotton could be added to Shaizar crops, as was understood from an Arabic source narrationFootnote 36. A recent study concluded that the agricultural production of the Levant was comparable to the production of European regions during the Crusader eraFootnote 37.

Sources have proven that the Franks of Antioch set out from Apamea and attacked the outskirts of Ḥamāh and Shaizar, and plundered the crops and animals on several occasions Footnote 38. Likewise, their control over Basarfut fortress in March 1104Footnote 39, al-Athārib and Zerdana in 1110Footnote 40, Artah castle in May 1105Footnote 41, as well as the castles of Rugia, Arcican, and RusaFootnote 42, Ashughr, and BakasFootnote 43, allowed them to penetrate east of the Orontes River and reach the fields of Aleppo (see Table 2). However, the Franks did not achieve expansionary results or did not want to expand.

Table 1. The important crops that the Franks of Edessa reaped from the borders of Aleppo and the tax value of some villages

Table 2. The most important crops that the principality of Antioch benefited from the Islamic countryside

Nicholas Morton comments that the Franks needed to maintain the momentum built up by the First Crusade and continue to convince their neighbours (many of whom possessed far greater resources) to remain or become quiescent. He adds that the relationship of Aleppo rulers with the Franks included only sporadic moments of conflict interspersed with periods of ‘peace’ and occasional instances of cooperationFootnote 44. Morton probably agrees with some scholars who argue the same point, such as Ernest Barker, who confirms that the profits the Franks obtained from these raids were limited and temporaryFootnote 45; Raymond Smail who argues that these raids were carried out with small forces and their purpose was to achieve greater gains and not necessarily plunder and sabotageFootnote 46; and Joshua Prawer who suggests that the Franks’ campaigns were out of economic necessity to create or safeguard their sources of income from the agricultural production of the landFootnote 47.

Accordingly, the Franks of Antioch employed their attacks as a way to conclude a suitable agreement that would provide them with regular access to agricultural supplies, as they did in their attack on Aleppo in 1118 when they forced its inhabitants to hand over the citadel of Aʿzāz and to cede to them the fields north and west of Aleppo, as well as a sum of moneyFootnote 48. What indicates the somewhat peaceful intentions of the Franks was that they approached the Muslim villagers of Aʿzāz and helped them cultivate their landsFootnote 49. In 1119, they asked the people of Aleppo to share the crops with themFootnote 50. This reflects the solicitude of Antioch’s Franks to cultivate the nearby Islamic countryside and preserve their share of its products and their endeavour to achieve this through a policy that varied between war and diplomacy.

This policy resulted in an agreement secured by the Franks in October 1120 with Ilghazi, the ruler of Aleppo, who granted them half of the villages in northern Aleppo and ceded to them Al-Bara, Kafr Tab, and Al-Ma’arrat, which facilitated the Franks’ access to the fields of Ḥamāh and Shaizar, as well as AleppoFootnote 51. Ilghazi also granted them half of the villages of Leylon-Afrin, Aʿzāz, Ma’arrat Maṣrīn, and some villages of Jabal al-Summāq. Additionally, the Arabic sources mentioned that Ilghazi shared with the Franks all the villages of western AleppoFootnote 52. That is, the Franks had at least half the crops of these regions, including grains, olives, cotton, fruit, almonds, pistachios, sesame, summāq, onions, garlic, and coriander (see Table 2)Footnote 53.

This agreement was the cornerstone of a relationship between Antioch and Aleppo that lasted for at least ten years, during which the principality of Antioch secured regular agricultural supplies. Therefore, the Franks solicited to confirm this agreement with Ilghazi in March 1122Footnote 54. Then, they documented it with his nephew Badr al-Dawla in April 1123, obtaining the fortress of al-Athārib, 35 km west of Aleppo and overlooking the most important roads with AntiochFootnote 55. According to Arabic sources, the result was that agricultural conditions improved in these areasFootnote 56.

The Franks imposed the same agreement on Aqsunqur al-Bursuqi in September 1125, following the difficult and painful siege on AleppoFootnote 57. Then, they got half of the crops of Jabal al-Summāq, west of AleppoFootnote 58. It is clarified that the Franks were igniting war with every new ruler of Aleppo to gain two benefits: renewing the agreement and having new gains. These agreements were certainly beneficial to them. According to Ibn Munqidh, the silos of Antioch were full of grain when Bohemond II came to power in 1126 and when he died in 1130Footnote 59. In other words, this ruler succeeded in securing his principality’s grain supplies throughout his rule.

The castles located east of the Orontes were the guarantor of feeding Antioch with these crops but at the expense of the markets and the livelihoods of the Islamic cities. Realising this situation, Imad al-Din Zengi destroyed al-Athārib in 1130Footnote 60. He surrounded Harim until the Franks gave him half of its villages’ taxFootnote 61. He raided Maʿarat al-Nuʿmān and Kafr Tab in 1133Footnote 62 and controlled them in 1137Footnote 63. His possession of these fortresses enabled him to seize Homs on June 30, 1138Footnote 64, and Baʿlabekk on October 16, 1139Footnote 65. Therefore, he paved the way to capture Edessa.

Zengi’s success in drawing a line for his country extending from Edessa in the north to the outskirts of Damascus in the south was fruitful. He preserved the villages and fields, extended his protection to the peasants, and secured the crops and food supplies for his cities. The manifestations of his success appeared in the abundant and cheap fruits and crops in the markets. Ibn al-ʿAdīm provided evidence in his classification of the prices of five main commodities that were sold before Zengi’s death in the markets of Aleppo, as follows:

In contrast, Zengi’s expansionist policy, or war of attrition, as Andrew Buck called it, negatively affected the Franks, as it reduced revenues from border agricultural lands, on which the authority to govern and organise military defence dependedFootnote 67.

Nur ad-Dīn continued his father’s efforts and annexed the fortress of Artah with several nearby castles in 1147Footnote 68. He took Apamea on August 1, 1149Footnote 69. Thus, the Franks were deprived of their most important outlet on the Orontes, which became their border with Muslim SyriaFootnote 70; consequently, their crops became limited. This argument was supported by two texts. The first was by Ibn al-Qalānisī, who declared that the Franks were forced to give up their influence in the western fields of AleppoFootnote 71. The second was a letter sent to the Templar Everard des Barres, circa 1150, which contained ‘that the Muslims shut up the Franks within the walls of Antioch and took away all the harvests and vintages’Footnote 72. With the occupation of Harim on August 18, 1164, the Franks lost their last outlet to the fields of AleppoFootnote 73. Realising this, Arab sources praised this eventFootnote 74.

The fall of the Harim was disastrous for the Franks. Its catastrophic consequences were not limited to the military aspect, as some argued that Antioch lost its military importanceFootnote 75to the point that the Franks were forced to sell or rent the castles east of the Orontes to the Hospitallers in an attempt to restrain Nur ad-Dīn Footnote 76. Moreover, the matter exceeded Antioch’s logistical loss, as its markets faced a food supply crisis. Michael the Syrian explained that wheat became scarce in Antioch in 1164 until half a measure was sold for a dinar and shortly disappeared from the marketsFootnote 77. This crisis was directly related to Antioch’s loss of Harim and its deprivation of the fields east of Orontes.

Tripoli and Jerusalem

The principality of Tripoli was coastal, and its area was not as large as the other principalitiesFootnote 78. Its capital, Tripoli, was bordered by the sea to the west and the mountain ranges of Lebanon to the eastFootnote 79. Therefore, its fields were not expected to meet the Franks’ need for agricultural supplies, especially grainsFootnote 80.

From the beginning, the Franks tried to control the Islamic rural suburbs that provided them with continuous supplies. In 1105, they tried to seize Raphanea, located west of Ḥamāh, which had a fertile suburbFootnote 81. A poem by Ibn Munqidh showed the extent of fertile agriculture in this region, especially grainsFootnote 82. The Franks also extended their control over the outskirts of Tripoli in the same yearFootnote 83. These rural suburbs stretched between the Beqaa and GhūṬa and were full of palm trees, vines, fruit, sugar cane, and olivesFootnote 84.

After the establishment of the Tripoli principality, the Franks attacked the fields of ḤamāhFootnote 85. In 1108-1109, they took Arqa on the eastern borderFootnote 86. An anonymous traveller visited the region in the mid-twelfth century and pointed out the importance of Arqa, overlooking the fertile fields of Ḥamāh to the northeast and its counterparts belonging to Baʿlabek in the southwestFootnote 87. Burchard confirmed that these fields, in addition to being full of various fruit trees, included villages, vast pastures, and numbers of Bedouins who owned abundant herds of sheep and camelsFootnote 88. Moreover, the large number of river mills in ArqaFootnote 89 denoted that the grain input was plentiful. This encouraged some to believe that a Frankish settlement arose around ArqaFootnote 90.

The Franks also penetrated the fields of Homs after they took control of ʿAkkār fortress, northeast of Tripoli, in 1109Footnote 91. This allowed them to monitor the fields and had, in 1142, fishing rights in the freshwater fisheries near HomsFootnote 92.

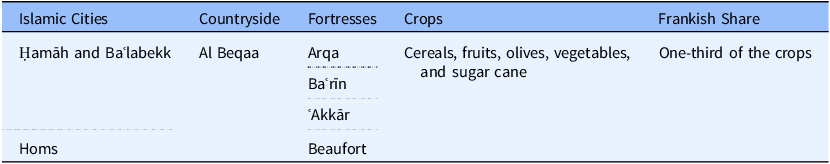

Consequently, the Franks secured a satisfactory agreement with Ṭughtekīn, atabeg of Damascus, in 1109, under which they obtained one-third of the crops of the Beqaa ValleyFootnote 93. This agreement was confirmed by Ṭughtekīn with Baldwin I, King of Jerusalem, in 1110Footnote 94.

Michael Köhler described this agreement as a sign of the balance of power between the two partiesFootnote 95, while Kevin Lewis did not consider its fruitful results, justifying that it was held for stereotypical military motivesFootnote 96. Heather Crowley relied on this agreement a lot, considering it proved how quickly the Franks adapted when they settled in the Levant and understood how to manage the Condominium properties, even if they did not interfere with how they were farmedFootnote 97.

This agreement was the pivotal axis of the logistical policy of the County of Tripoli and a safety valve that secured a share of crops for a quarter of a century and even permitted them, according to Bar Hebraeus, to practice grazing in the Islamic countryside, to the eastFootnote 98. The castles of Baʿrīn, Beaufort, and Arqa were the main guarantors of the implementation of this agreement (see Table 3). Baʿrīn and Beaufort allowed them to put pressure on the Muslim villages in the Beqaa, control the southern access to this plain, and ensure communication between Antioch and JerusalemFootnote 99. Baʿrīn also empowered the Franks from the villages of Ḥamāh and remained a threat until Zengi seized it in August 1137Footnote 100. Arqa Castle enabled the Franks to monitor and threaten the fields of Baʿlabekk and remained a danger to Ḥamāh until the 1170s when Nur ad-Dīn b. Zengi destroyed it in 1172, which deprived Tripoli of a vital outlet to the eastern hinterlandFootnote 101. However, the Franks of Tripoli had the Castle of Krak des Chevaliers, which they sold to the Hospitallers in 1142Footnote 102. This castle threatened the fields of Homs and Ḥamāh until the 1180s, as Ibn Jubayr pointed outFootnote 103.

Table 3. The important crops that the principality of Tripoli benefited from the Islamic countryside

As for the Kingdom of Jerusalem, it was the poorest in providing food supplies compared to other Crusade principalities. It did not have rivers but obtained water from wells, reservoirs, and cisternsFootnote 104. Moreover, the lands of the Kingdom were planted with limited wheat, barley, vines, figs, olives, and other fruitsFootnote 105, which did not meet the food needs of its peopleFootnote 106. This was confirmed by Fulcher of Chartres’s account, ‘Because the area was dry, unwatered, and without streams our men as well as their beasts suffered’Footnote 107, Orderic Vitalis comment on Jerusalem’s economic value, ‘noting that the land thereabouts was parched, not suitable for grazing, possessing few trees, and having only a few vines and olives’Footnote 108, Burchard’s observation about the Kingdom’s need for Damascus fruitFootnote 109, and the content of King Fulk’s letter mentioned above.

Contrary to Ekkehard’s dreamy storyFootnote 110, King Baldwin I realised the deficit in agricultural production in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, especially with the constantly arriving pilgrims, and that he lacked an alternative to obtain provisions and supplies. Additionally, he fully realised the seriousness of the Kingdom’s geographical and geopolitical situation, which Fulcher explained by the weakness of aid from the sea and the landFootnote 111. Therefore, Baldwin created his policy based on two parallel frames. First, he sought to seize the coastal cities that were still in the control of the FatimidsFootnote 112, which would enable him to facilitate communication with the commercial cities of Western Europe to supply him with the needs by seaFootnote 113. Second, he was keen to penetrate the Islamic interior to secure his Kingdom geopoliticallyFootnote 114 and to provide an alternative in case of a lack of supplies from the seaFootnote 115. Thus, Baldwin held the stick from the middle, establishing for his successors a balanced policy that lasted until the end of the first half of the twelfth century.

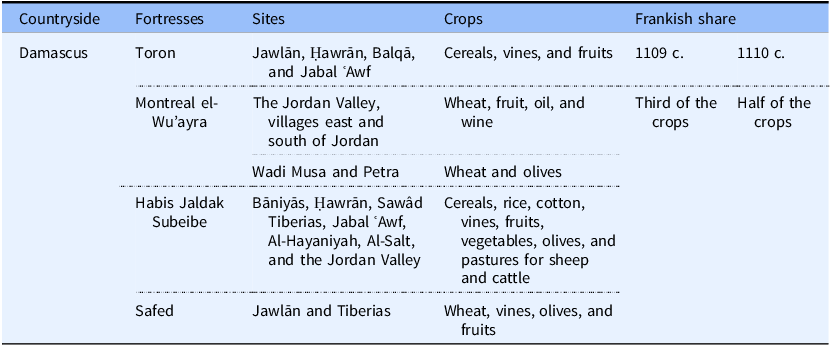

Wheat was the most important requirement of Jerusalem kingsFootnote 116, who sought to gain it from the fields of Damascus, which they accessed via the Jawlān. Bāniyās, 24 miles from Damascus, was the main entrance to this countryside, extending from the shores of Tiberias in the south to Ḥawrān in the eastFootnote 117. Bāniyās countryside was distinguished by growing wheat, rice, and cotton. Thus, Al-Muqaddasī called it ‘the Granary of Damascus’Footnote 118, and Ibn Jubayr described it as spacious ploughsFootnote 119. The hypothesis of wheat cultivation in Bāniyās was demonstrated by discovering the remains of a Frankish River millFootnote 120. In addition to Bāniyās, the Damascus borders included other agricultural sites that lured the Franks, such as al-Sawâd Tiberias, Ḥawrān, Balqāʾ, and Jabal ʿAwfFootnote 121. These areas were so rich in crops and livestock that they could help provide supplies for the Frankish siege of Sidon, according to Albert of Aachen’s confirmationFootnote 122.

The Franks built castles and fortresses on the outskirts of Damascus, such as the castle of Safed in 1102, to control the road between Damascus and AcreFootnote 123 and to monitor the fields of Bāniyās, whose city was only 23 km away from SafedFootnote 124, and the castle of Toron between Mount Lebanon and Tyre, in 1104, at the same distance from BāniyāsFootnote 125. These two castles enabled the Franks to threaten the agricultural villages southwest of Damascus: Ḥawrān, Jabal ʿAwf, and Balqāʾ. In the same vein, the Franks sought to build al-‘Al fortress on Tiberias outskirts (Al-Sawâd) in 1105, but it was destroyed by Ṭughtekīn, atabeg of DamascusFootnote 126. The Franks were keen to possess Al-Sawâd region, which was producing wine, grains, and olives, according to William of TyreFootnote 127. Al-Idrîsî wrote about date cultivation and described small boats that used to travel from Zoghar, south of Tiberias, loaded with grains and dates until they reached Jericho, Jerusalem’s gateway to the Transjordan regionFootnote 128.

One of the significant results of the Frankish policy of building fortresses was that Ṭughtekīn rushed to conclude an agreement with Baldwin I in the summer of 1109, stating the division of the crops of Al-Sawâd and Jabal ʿAwf regions: A third for the Franks, a third for the Damascenes, and a third for the peasants of the two regionsFootnote 129. It seems one-third was insufficient for the Kingdom of Jerusalem, so Baldwin decided to increase his share. Between 1109 and 1110Footnote 130, he built Cave de Sueth/Habïs Jaldak, a new fortress, in the Lower Yarmouk Valley, 16 miles south east TiberiasFootnote 131 and cooperated with the Count of Tripoli in threatening Ṭughtekīn, who agreed in July 1111 to give the Kingdom of Jerusalem half of the crops of the aforementioned regions, in addition to new ones, namely al-Hayaniyah, according to Ibn al-QalānisīFootnote 132, al-Ḥannāna, al-Salt, and the Jordan Valley, according to Ibn al-AthīrFootnote 133.

These areas were abundant in grains, as the production of al-Salt and Balqā in 1192 reached six thousand Gherara (approximately 480,000 kg)Footnote 134. The regions of Upper Jordan were known for the cultivation of sugar cane, according to Daniel the Monk, who mentioned a forest belonging to wild boars and a number of leopards and lionsFootnote 135. The Jordan Valley (al-Ghawr) was also known for the cultivation of sugar cane, bananas, palm treesFootnote 136, and a variety of vegetablesFootnote 137.

The agreement of 1111 AD was a turning point in the mutual relationship between Jerusalem and DamascusFootnote 138. It shaped their interrelationship with peace and tranquillity for most of the first half of the twelfth century. It gradually ensured that the Jerusalem Kingdom secured its food supplies. Nicholas Morton emphasised the desire of both sides to maintain peace between them. However, he ignored, for the reasons he gave, the keenness of both sides to cultivate the border area between themFootnote 139, which necessitated peace between both sides.

There is no doubt that Steve Tibble was right in saying that stable, well-managed, sedentary societies had reserves of food and could, just, absorb temporary or infrequent climatic shocksFootnote 140. In confirmation of that, the critical historian Ibn al-Qalānisī noted that establishing security in Damascus villages adjacent to the Franks and regularly cultivating crops could only result from a peaceful relationship between the rulers of Damascus and the Frankish kings, stating that, ‘The correspondence between Ṭughtekīn, Atabeg of Damascus, and Baldwin, King of the Franks, was established to make a truce, reconciliation, and peace in order to populate the villages and secure the wayfarers’Footnote 141. Consequently, both sides were keen on renewing the aforementioned agreement in 1112Footnote 142, 1113Footnote 143, 1115Footnote 144, and 1119Footnote 145.

Within three years, the Franks of Edessa and Antioch renewed their agreements with the Muslim rulers of northern Syria, which had a positive impact on the Frankish markets. Fulcher points out, ‘This year (1122) ended as abundant as the previous year, in products of all kinds, whatever is reaped in the fields. A measure of wheat sold for a denarius, or forty for a golden piece’Footnote 146.

The dividing line in the Condominium between Muslims and the Franks was unclear but was rather fuzzy or fluid, as Denys Pringle puts itFootnote 147. Ronnie Ellenblum suggests that the borders between Muslims and the Franks were not clear, at least in the first half of the twelfth centuryFootnote 148. The matter can be further clarified by saying that the Franks, in view of their expansionist desire, did not have in their interest to define borders between themselves and the Muslims as long as the latter did not have a strong rulerFootnote 149.

Accordingly, the rural suburbs of Damascus became a vital target for the Franks, who viewed them as an inexhaustible warehouse of agricultural supplies. Therefore, according to Ibn al-Athīr, in 1128, the Franks agreed with one of the Damascene Shiites to hand over Damascus to them in exchange for TyreFootnote 150. Although this story was not mentioned in another source, it confirms the importance of Damascus to the FranksFootnote 151. Ibn al-Athīr even justified their attack on Damascus’s countryside in the following year as a result of the failure of this agreement. He noted that the Franks’ concern was the possession of crops from the suburbs of Damascus, especially ḤawrānFootnote 152. Michael the Syrian addressed this attack, reporting that it was due to the interruption of supplies from Damascus to the Franks, ‘En 1129, Les Turcs, de Damas, s’étaient emparés des défilés pour qu’on ne pût ravitailler les Francs’. Hence, the Franks imposed on Būrī, ruler of Damasus, an annual tribute of twenty thousand dinarsFootnote 153.

Bāniyās remained as a vital target for Jerusalem’s Franks. When Muʿīn ad-Dīn Unur, ruler of Damascus, sought their support in the war against Zengi, the Franks insisted on controlling Bāniyās, which was achieved in July 1139Footnote 154. The importance of this region for Jerusalem was evident from the narration of William of Tyre, Ernoul, and Ibn Jubayr, who confirmed that the sharing of its crops and taxes remained valid between Muslims and Franks until 1182Footnote 155.

The importance of Damascus to the Franks was also confirmed during the Second Crusade (1147–1149). The commanders of this expedition sought to seize this city, although their coming was mainly for the fall of Edessa. None of the contemporary sources provided a convincing reason for the expedition’s deviation towards Damascus. Claude Cahen even confirmed that the emergence of the name Damascus as a target of the campaign was surprisingFootnote 156.

Some scholars suppose that the expedition’s goal was to possess the rich villages and fields of Damascus to provide an uninterrupted food supply to the Kingdom of JerusalemFootnote 157. William of Tyre hinted that the Kingdom would not allow Nur ad-Dīn to control a vital resource like DamascusFootnote 158. This proposal clearly explains why Baldwin III attacked the outskirts of Damascus before the advent of the CrusadeFootnote 159. This King tried to seize three fortresses in ḤawrānFootnote 160 and reconstructed el-Wu’ayra Castle in the Petra region in 1144/1145Footnote 161, as he was in a feverish race with Nur ad-Dīn. Baldwin III did not cease his attacks after the failure of the Second Crusade, to the point that the peasants of Ḥawrān in 1149 were not safe in transporting their crops to Damascus except under the protection of Unur forcesFootnote 162.

Nur ad-Dīn employed these attacks as a pretext to invade DamascusFootnote 163. Abaq, ruler of Damascus, was on the horns of a dilemma. When he hired the Franks in March 1151 to repel Nur ad-Dīn, they demanded getting crops of Ḥawrān and some of the suburbs of DamascusFootnote 164. Then, they attacked the fertile fields of Bosra, south of Damascus, in August 1151. On the other side, Nur ad-Dīn raided and plundered the crops and livestock of other Damascene fields in Ḥawrān, GhūṬa, and Marj RahitFootnote 165. Consequently, the greed for the crops and supplies of Damascus was distributed between the Franks and Nur ad-Dīn. The farmers and people of Damascus paid a heavy price.

As Nur ad-Dīn’s pressure on Damascus increased, the Franks turned to possess the rest of the eastern Mediterranean coast to ensure their communication with Europe by sea and create a strong defensive line to confront the interior rising Islamic stateFootnote 166. Ascalon was the last coastal city they captured on August 12, 1153Footnote 167. William of Tyre praised the positive consequences of the Ascalon capture, confirming that the peasants began to plant the countryside with grains and fruitsFootnote 168. This suggests that the Franks’ goal in obtaining Ascalon was to provide an alternative to the supplies of Damascus, whose fall into the hands of Nur ad-Dīn had become inevitable.

William of Tyre described Damascus’s seizure by Nur ad-Din on May 2, 1154, as a disaster for the Franks. He explained that the former ruler of Damascus, who was weak and used to pay an annual tribute to the Franks, had been replaced by a strong ruler who would disturb the Franks’ tranquillityFootnote 169. The severest consequence was cutting off agricultural products from Damascus to Jerusalem, which happened when grains became scarce in the markets of Jerusalem in 1154 to the point of famine. William of Tyre said, ‘In 1154, a severe famine spread over the whole land, it took away our main support, bread, so that a measure of wheat (five bushels) was sold for four gold pieces’Footnote 170.

William did not explain the reason for this crisis other than his usual religious intimidation. However, there appears to be a close connection with Nur ad-Dīn ’s seizure of Damascus. Several threads supported this hypothesis. It was the custom for the Franks of Jerusalem to compensate for their food supply deficit with Damascus crops by purchasing, sharing, or paying tribute, part of which was grains or through raiding, if necessary. But Damascus was besieged by Nur ad-Dīn in 1153, and its markets were in crisis, as grains became scarce until a measure of wheat (al-Gherara) cost twenty-five dinarsFootnote 171. Additionally, its fall prevented reaching the agricultural supplies to Jerusalem, threatening its people with famine. William of Tyre commented that the abundant grain found by the Franks in Ascalon saved them from famine, as he confirmed that the grain shortage crisis occurred in the year following the fall of Ascalon, raising contradiction in his narration.

Jean Richard tried to find a way out of William’s narration confusion; he mentioned that the capture of Ascalon was in 1154, not 1153Footnote 172, despite the Arab sources agreeing with William on the latter year!! In his turn, Richard did not reveal the causes of the food shortage crisis in Jerusalem’s markets, which has no proper explanation other than that it was a result of Nur ad-Dīn ’s seizure of Damascus. As for the return of wheat to the markets of Jerusalem, William of Tyre mentioned that it happened after the Franks cultivated the countryside between Jerusalem and Ascalon with grains until the land’s productivity increased sixty times compared to the previous era. William, supported by Jean Richard, confirmed that Ascalon’s cultivation was self-sufficient for the Jerusalem Kingdom in the following years.Footnote 173Was this true?

To say that cultivating a new territory would provide a portion of the Kingdom’s supplies was entirely plausible, but William’s description of the land’s productivity and emphasis on the Kingdom’s self-sufficiency were undoubtedly exaggerated. Actually, the richest deltas known did not reach this productivity, and the travellers who visited Jerusalem beginning in the tenth century did not reach, in their most sentimental descriptions, William’s estimatesFootnote 174. At the same time, Damascus witnessed an abundance of crops after Nur ad-Dīn stimulated its cultivation and renewed and maintained its irrigation systems, suggesting that the Kingdom of Jerusalem tended to compensate for the deficit in their supplies from Damascus. Thus, in the year following the fall of Damascus, the Franks entered into negotiations and concluded peace with Nur ad-Dīn Footnote 175.

The Franks also kept Bāniyās because they were aware of the permanent agricultural and animal supplies it providedFootnote 176. William of Tyre mentioned that the Muslims were grazing herds of cattle and horses in the vicinity of Bāniyās according to an agreement concluded with King Baldwin IIIFootnote 177. Undoubtedly, William adopted the story of Albert of Aachen, who classified grazing animals into camels, cows, sheep, and goatsFootnote 178. In general, Bāniyās provided important animal production to the point that Baldwin III permitted the Hospitallers to share its pastures in 1157Footnote 179. The utilitarian exchange between the Franks and Muslims continued until the year 1182 AD, as noted by Ibn Jubayr, who said, They were sharing the crops, and their herds were grazing together. Footnote 180

In sum, Nur ad-Dīn realised that the Franks’ possession of Bāniyās Castle motivated them to threaten the fields of Damascus, so he captured it in November 1164. He put pressure on the Franks of Jerusalem until they granted him half of Tiberias’s cropsFootnote 181. Thus, his efforts not only resulted in the security of his villages and fields but also threatened the Franks’ crops and agricultural supplies. Raymond Smail commented on this, saying: ‘In this way the Christian rulers lost the military force which those lands had supported’ Footnote 182 .

The Franks and the management of the rural countryside: Feudal influences and taxes

The Franks transferred almost their feudal system to the LevantFootnote 183and were keen to provide food supplies, such as wheat, barley, and oil, as well as animal fodder for their vassals as soon as they swore vassalageFootnote 184. With the inability of their principalities to give sufficient agricultural production, the lords sought to provide fiefdoms, landed or monetary, in the Islamic countryside adjacent to the Crusader cities in the LevantFootnote 185, which was an easy solution compared to the successive difficulties facing the arrival of European supplies.

If the Franks were unable to acquire agricultural supplies, they imposed royalties on the Muslim rulers, which naturally helped them purchase agricultural productsFootnote 186. Arabic sources detailed the tributes that the Franks imposed on their Muslim neighbours, at least until the 1130s. The Aleppans paid to the Franks of Antioch an annual sum ranging from twenty to thirty thousand dinars and several horsesFootnote 187. They pledged to the Franks of Edessa in 1127 twelve thousand dinars annuallyFootnote 188. Shaizar paid four thousand dinarsFootnote 189, and Ḥamāh paid two thousand dinars to the Franks of Antioch Footnote 190 . Furthermore, Tyre paid seven thousand dinars to the kings of JerusalemFootnote 191. The rulers of Damascus paid twenty thousand dinarsFootnote 192, and Homs paid the Franks of Tripoli four thousand dinarsFootnote 193. Baʿlabekk committed an annual tribute to the latter, according to Jacob of Vitry, who did not specify its amount.Footnote 194 The Franks made the time to pay these taxes coincide with the harvesting of cropsFootnote 195. Perhaps, they allowed the Muslim rulers to sell their crops or took an in-kind portion of the tribute, as Bar Hebraeus confirmed: ‘The Arabs in Aleppo, Hamah, Homs and Damascus paid tribute to the Franks. In Aleppo they paid half of their crops to the Franks’Footnote 196

The Franks benefited from the Right of Conquest that they applied on the eve of their invasion of the Levant, which allowed them to divide the villages adjacent to their Levantine principalities into small fiefdomsFootnote 197, stripping off their ancient Hebrew and Arabic names and giving them names of the Frankish familiesFootnote 198. This right encouraged young knights to undertake military adventures in the countryside surrounding the Kingdom of Jerusalem. They penetrated Transjordan, for example, which became subordinate to the royal crown and operated under the feudal systemFootnote 199.

Over time, the Muslims and the Franks realised that mutual border clashes would not benefit them. For example, when the Franks of Galilee, in their first years, attacked the Transjordan fields, destroyed crops, and plundered livestockFootnote 200, they caused a scarcity of food and a rise in prices in the markets of DamascusFootnote 201. On the other hand, such clashes heralded the interruption of trade coming from deep within Syria or at least prevented the establishment of markets on the Islamic borders. As a result, valuable goods, especially spices, oil, sugar, cotton, and linen, were not imported to the Crusader citiesFootnote 202, causing a loss for the European commercial cities which carried these goods and sold them in other markets at high pricesFootnote 203. The Franks realised then that their wars against Damascus were not in their interest. Nicholas Morton comments that the rulers of Jerusalem Kingdom had no immediate ambition to stage a major campaign against Damascus but were content to focus their attention on the coast and TransjordanFootnote 204.

Based on these considerations, the peace treaty that Baldwin I concluded with Ṭughtekīn in 1115Footnote 205was not for military-political reasons, as Fulcher and Ibn al-Athīr imaginedFootnote 206, rather, for reasons related to the food capacity of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Kingdom had limited agricultural areas, which experienced human and natural disasters, e.g., the disaster following Baldwin’s defeat in the Battle of Jisr al-Sinbara, on July 4, 1113, where the fields extending between Jerusalem and Acre were devastated and devoid of cropsFootnote 207. In the spring of 1114, locusts attacked and destroyed the kingdom’s cropsFootnote 208. Consequently, Baldwin’s insistence on making peace with Ṭughtekīn in the following year was an inevitable result of the devastation of his Kingdom’s crops. Since the peace agreements between the Franks and the Muslim rulers were followed by the latter paying tribute, part of which came in the form of in-kind materialsFootnote 209, it is likely that Baldwin I sought to compensate food supply deficit from Damascus’s crops by confirming the agreement with Ṭughtekīn, secured in 1109 and was renewed in 1110Footnote 210. Thus, Baldwin made a safe way to the fields of Bāniyās and ensured his access to the fields of Transjordan, from which he brought crops and transported Christian farmers to the outskirts of JerusalemFootnote 211.

Baldwin I established a pragmatic principle for the Kingdom, i.e., to follow a cooperative or hostile policy with the Muslims to the extent that it secured its supplies. The effect of his pragmatism was evident in the policy of his successors, as Baldwin II granted tax exemption, on January 31, 1120, to both Muslim and Christian farmers and merchants on the grains, barley, vegetablesFootnote 212, beans, lentils, and chickpeas they brought to the Kingdom’s marketsFootnote 213.

This decree brought undoubted positive outcomes to the Kingdom of Jerusalem. William of Tyre explicitly pointed out the connection between this decree and the availability of agricultural supplies in the Kingdom’s marketsFootnote 214. Joshua Prawer praised the outcomes of the decree, attributing the stability of the Kingdom in the second quarter of the twelfth century to the surplus of agricultural products from the new rural centres, coinciding with the commercial activity that the Kingdom experienced after seizing the seaports.Footnote 215 Moreover, this decree encouraged Ronnie Ellenblum to argue that the Kingdom enjoyed peace in the following yearsFootnote 216. However, a question arises: What were the reasons for issuing this decree?

There is an undoubted connection between this decree and the bad conditions the Kingdom went through before its issuance, as the Kingdom experienced four lean years when its crops were destroyed by locusts and rats, which made grain scarceFootnote 217, bread disappeared, and famine afflicted Jerusalem in 1119-1120, as Michael the Syrian and William of Tyre confirmedFootnote 218. Hans Mayer believes that the decree was issued due to these circumstancesFootnote 219, leading to the hypothesis that Baldwin II sought help from the Islamic countryside to meet his food deficit. Therefore, Prawer’s judgement that the peripheral areas of the Kingdom of Jerusalem were economically less important than the coastal ports was inaccurateFootnote 220. The truth is that they were equally important, but the building of a unified state by the Zengids since the 1130s prompted the Kings of Jerusalem to direct their attention towards the supplies coming by sea.

Due to the scarcity of evidence for agricultural regimes in Palestine and Syria in the medieval periodFootnote 221, there is no definitive opinion on the method of managing the countryside joint villages between the Franks and Muslims in what is known as muqasama. Perhaps an agreement concluded in 1271 between the Mamluk Sultan Baybars and the Hospitallers over the properties of Lod (Lydda) Castle reflected a closer picture of what was happening. The text reads: ‘It is agreed to share crops, pastures, water, mills, and houses… provided that the Sultan sends a representative and the Hospitallers send a representative. Neither of them shall decide a matter without consulting the other’Footnote 222. It could be understood that the administration of the Condominium was equal between the Franks and the Muslims. Ibn al-Qalānisī confirmed that the agreement of 1157 between Nur ad-Dīn and Baldwin III required the presence of Muslim delegates to administer Bāniyās countrysideFootnote 223. Ibn Jubayr confirmed the same information during his journey in 1183Footnote 224.

While the Arabic sources showed the powers of the Arab delegate, which varied between financial and judicial burdensFootnote 225, it was not known precisely what powers the Frankish delegate had. The latter might be the ra’īs who appeared in Frankish documents and relied upon to administer the Casals of their principalitiesFootnote 226. John of Ibelin noted that the ra’īs had judicial powers, and Christopher MacEvitt added military-administrative powers to himFootnote 227. Prawer and Benvenisti added financial powers to the ra’īs and made him an active element in the Frankish feudal administration of the villageFootnote 228.

The ra’īs was entrusted with activating the feudal fees applicable in Europe, such as providing hospitality duties to the lord when he visited the villageFootnote 229, collecting a share of the crops, and catering tax paid three times a year in cash or in-kindFootnote 230. Additionally, he supervised the collection of crops, estimated the terraticum assigned to the feudal lord, which amounted to a third, and then delivered them to his agentFootnote 231. The Franks mostly kept a raw share of the crops to supply hospitals, churches, and monasteriesFootnote 232.

It is worth noting that the Franks recruited Muslim ra’īs to manage their villages. Ibn al-ʿAdīm provided an example of this, reporting that the Franks entrusted the management of the villages of al-Athārib to one of its citizens, i.e., Hamdan b. Abdul Rahim (1068-1147)Footnote 233. Benjamin Kedar mentioned that Hamdan worked within the existing feudal and administrative system in the Frankish villages, so he served as a ra’īs Footnote 234. In addition, some documents contained Arabic names of village chiefs, which encouraged Benvenisti to confirm that all villages in the Crusader principalities were supervised by Muslim leadersFootnote 235. In the same context, Claude Cahen and Kevin Lewis did not rule out that the ra’īs in the countryside of Antioch and Tripoli were MuslimsFootnote 236. Alan Murray opposed this orientation, asserting that the Franks, in their hierarchical dealings with the inhabitants of the Levant, placed the Muslims in the lowest rankFootnote 237. In this context, Buck believed that the urban areas of Antioch witnessed ra’īs from the local Christians, even if they spoke ArabicFootnote 238. It is clear that the Muslim ra’īs worked in the Frankish villages rather than the cities, as Ibn Jubayr mentioned, ‘The Franks owned the cities, while the villages belonged to the Muslims’Footnote 239. On the other hand, documents show that some Frankish villages within the Kingdom of Jerusalem had a head called Baillus Footnote 240, which increased the likelihood that the Franks adopted the experience of Hamdan only in the Islamic villages with shared management. Perhaps discussing the issue of Frankish settlement in the Islamic rural suburbs, which remains a thorny issue, would support this conclusion.

Sources have very brief accounts of the Frankish settlementsFootnote 241. William of Tyre, for example, mentioned that many civilians were residing near Bāniyās Castle, and King Baldwin III was inspecting their conditions, making it likely that a Frankish settlement existedFootnote 242. William’s account of the countryside of Montreal Castle suggested that there was a settlementFootnote 243, as well as another near el-Wu’ayra castleFootnote 244. A huge settlement was near Karak Castle, which relied mainly on local Christians (Syriacs and probably Armenians)Footnote 245. While there were strong settlements in northern Syria around the castles of Aintab, Marash and Tell Bashir, the same was not the case with the castles west of Aleppo – east of the Orontes – whose settlements were difficult to judge precisely, as they were always battlefields between the rulers of Antioch and their counterparts in Aleppo. A settlement of about 700 Frankish knights ruled Jabal al-Summaq regionFootnote 246, and another county arose around the fortress of al-Athārib. However, they undoubtedly disappeared before the end of the 1130s in the face of Zengid’s expansionFootnote 247. These accounts encouraged Joshua PrawerFootnote 248, David JacobyFootnote 249, Raymond SmailFootnote 250, and Christopher TyermanFootnote 251 to argue that Frankish settlements existed, but only next to castles.

Claude CahenFootnote 252, Meron BenvenistiFootnote 253, Hans MayerFootnote 254, Raymond SmailFootnote 255, and Jonathan PhillipsFootnote 256 doubted the success of Frankish settlements in rural areas. Jonathan Riley-Smith points out that there were active efforts by the military Orders to establish Frankish settlements in the countryside adjacent to the Muslim cities, especially the Hospitallers, who had previously obtained papal support for the establishment of churches and cemeteries on the Muslim frontier. However, the Hospitallers did not seem to have succeeded in establishing permanent settlements until the middle of the twelfth century, and they were more successful in the suburbs of Jerusalem than in the suburbs of Antioch and TripoliFootnote 257. Ronnie Ellenblum confirmed that the Franks imposed some features of their rural life in Europe on the villages of the LevantFootnote 258 and tended to build fortified settlements on the outskirts of Islamic cities outside their control, such as AscalonFootnote 259. Although Denys Pringle questioned their usefulness as conclusive pieces of evidence of Frankish settlementsFootnote 260, Ellenblum relied on demographic assumptionsFootnote 261and archaeological finds in Palestine to confirm that many Frankish agricultural settlements were established next to fortresses during the early days of the Kingdom of JerusalemFootnote 262. Boas and Barber were motivated by this idea, stressing that the settlements of Jerusalem had succeeded in supplying the Kingdom with agricultural suppliesFootnote 263. However, Ellenblum did not object to Benvenisti’s strict ruling that the Frankish settlement efforts were unsuccessfulFootnote 264.

Nicholas Morton addressed the demographic aspect when discussing the decline in the number of Franks militarily, saying: ‘What was needed was a settler population large enough to marshal sufficient forces to drive away an aggressor in the event of a major battlefield reverse. The Crusader States never possessed this kind of manpower and this deficiency goes some way to explaining their major territorial loses following the defeats in front of Muslims. To this extent at least, limited manpower reserves were a major problem’Footnote 265. This is what Steve Tibble alluded to in his analytical context of the Crusader strategy in the LevantFootnote 266.

Heather Crowley discussed the settlement issue in detail, using archaeological research. She took the remains of bakeries, mills, and olive presses, which were apparent features of the Frankish settlements in the Levant, as a criterion for judging the presence of Frankish settlements in the rural areas between the Franks and Muslims. Crowley did not find a convincing argument except for what was proven by the remains of Frankish ovens and mills in Montreal and some bread ovens (tabuns) in the Krak des Chevaliers castle overlooking the fields of Homs and Ḥamāh. She argued that the Franks were indifferent to agriculture in the countryside of their principalities. However, she did not deny their awareness and knowledge of the tax system in force in Islamic villages, from which they benefitedFootnote 267. Micaela Sinibaldi supported the hypothesis of the presence of strong Frankish settlements. She made a great effort to examine the archaeological remains of five Frankish castles in Transjordan and beyond the Dead Sea: Montreal, Karak, Al-Silaʿ, Habis Jaldak, and al-Wuʿayra, considering them as settlement bases (see Table 4). Sinibaldi also confirmed their strategic importance in securing the southern entrance to the Kingdom of Jerusalem and monitoring the trade route between Cairo and DamascusFootnote 268. In this way, she somewhat contrasted with Tibble, who entrusted the task of settlement to the inner castles of the FranksFootnote 269.

Ultimately, the hypothesis of the presence of Frankish settlements in the Islamic hinterland could be accepted, but these settlements were more firmly established in some suburbs and possessions of the Kingdom of Jerusalem in Transjordan and the Dead SeaFootnote 270. These settlements were based mainly on the local Christians, and their presence did not contradict the fact that local villagers controlled the surrounding landsFootnote 271. As for the Franks, the successive wars were enough to eliminate their rural settlementsFootnote 272; therefore, it is logical that they would prefer to live in castles and fortified citiesFootnote 273and welcome shared villages to be administered according to agreements with the Muslim rulers.

Arabic sources mentioned vital information about the number and financial income of Islamic or Frankish-Islamic villages adjacent to rural fortresses. The villages of Karak, for example, numbered four hundredFootnote 274, and villages of Aʿzāz were three hundred with a tax of eight hundred thousand dirhamsFootnote 275. The tax of Harim villages was five hundred thousandFootnote 276, and the tax of Tell Bāshir villages was three hundred thousandFootnote 277. The Franks got half of that income (Tables 1 and 2). In addition to the rest of the areas stipulated in the treaties, the sources did not specify their tax. Concerning the fertility of their villages and the abundance of crops, it is likely that their tax was close to what was previously mentioned.

However, it seems that the Franks imposed additional feudal taxes on the Muslims of the shared villages. Thus, Joshua Prawer and Meron Benvenisti traced the feudal system in Jerusalem. For example, the Franks imposed on the Muslim villagers near the fortress of Toron a chicken and ten eggs, one kilo and three hundred grams of cheese, and twelve golden bezants for every carruca Footnote 278 . The Franks possibly applied this system in all other shared villages. Ibn Jubayr stated that the land tax (terraticum) amounted to half of the crops.Footnote 279. He undoubtedly meant the rural suburbs of Bāniyās, whose crops were divided equally according to the agreement of 1111Footnote 280. Then, Ibn Jubayr referred to two other taxes, ‘A tax of one dinar and five carats on each head, and a low tax on the fruits of the trees’ Footnote 281 . Prawer explained that the fruit tax was on fruit and olive trees, estimating it to be one-third of the cropFootnote 282. He added an in-kind tax on wax and honeyFootnote 283, while Runciman suggested that Muslims also paid the dime tax to the Latin ChurchFootnote 284. Perhaps this was part of the agricultural system imposed by the Franks, which military religious Orders played a role in developing, as they focused on vital crops, such as wheat, olives, cane and grapesFootnote 285.

Muslims did not object to the Franks managing their villagesFootnote 286 and paid the money they owedFootnote 287, which helped facilitate agriculture and regular tax collection. Ibn Jubayr confirmed this situation when describing the Bāniyās countryside, emphasising the good relationship between the Muslims and the Franks. He said, ‘The Muslims were friendly with the Franks’ and expressed his regret that the Muslim villagers did not find such treatment from their rulersFootnote 288. Despite its conflict with contemporary accounts about the oppression of the Franks on MuslimsFootnote 289, this narration encouraged some researchers to argue that a modus vivendi imposed itself on the relationship between the Franks and their Muslim neighbours, which created a beneficial or pragmatic exchange between themFootnote 290. This coexistence was a life necessityFootnote 291, as it prevented the occurrence of famines that might result from the invaders’ settlementFootnote 292. It is noted that this harmony contradicted MacEvitt’s pessimistic view of ‘Rough Tolerance’Footnote 293. Heather Crowley also doubted this harmony, declaring that power-sharing in the shared rural villages was unclearFootnote 294. However, this did not prevent an Arab scholar from concluding that the early Crusader presence in the Levant did not harm Muslim farmersFootnote 295.

Some sources indicate that the Franks insisted on being friendly with the Muslim farmers in the shared villages to ensure the management of these villages and the collection of their taxes and to secure permanent communication channels to preserve their shares of agricultural supplies. For instance, Ibn al-ʿAdīm reported that Tancred, Emir of Antioch, was keen to improve his relationship with the peasants of al-Athārib and encouraged them to cultivate their fields. He even obligated the ruler of Aleppo to return the women of these peasants who had fled during the Frankish siege of al-Athārib CastleFootnote 296. At that time, the Muslim peasants in these areas realised that it was better to reconcile with the Franks to preserve the fields they shared. Both parties were convinced that crop safety ensured their food security. This was demonstrated in Ibn al-ʿAdīm’s note about the events of 1118, in which crop spoilage due to environmental reasons caused high prices in Antioch and Aleppo simultaneously ‘The famine became severe in Antioch and Aleppo, because the crops were damaged and the wind hit them when they ripened, destroying them’.Footnote 297. William of Tyre praised the Frankish-Islamic cooperation and noted its fruitful impact in cultivating the fields of the Blanche-Garde fortress near Ascalon, which provided food supplies for the FranksFootnote 298.

Albert of Aachen presented another account that Baldwin II allowed the Muslims to graze their herds in Bāniyās region and received four thousand bezants from them in returnFootnote 299. The Franks were keen to provide justice to the Muslim villagers. Ibn Munqidh told a funny story, dating to 1140/1141, ‘The Frankish ruler of Bāniyās looted sheep from an Islamic village called Al-Shu’ara’, ignoring the treaty concluded with Mu’in ad-Din Unur, Ruler of Damascus. The latter sent Ibn Munqidh to convey the news to King Fulk, who ordered seven knights to investigate the case. They judged to fine the ruler of Bāniyās four hundred dinars’Footnote 300.

Theoderic mentioned that the farmers of the villages extending north of Galilee, on the road between Bāniyās and Acre, were Muslims. He explained that the presence of these farmers was based on the approval of the Frankish kingsFootnote 301. This point was confirmed by the jurist Ḍiyā’ ad-Dīn Al-Muqaddasī in his narration about the Muslims of Nablus before 1156Footnote 302. Also, it was confirmed by Arnoul in his reference to Amalric’s welcome of the increase of Muslim peasants in the suburbs of Jerusalem, which aroused the anger of Thoros II, King of Armenia, who offered to replace these peasants with thirty thousand ArmeniansFootnote 303. Joshua Prawer tried to explain Amalric’s position, providing a demographic basis that the number of Franks three or four generations after their landing in Jerusalem was about one hundred and twenty thousand, and they were mainly distributed among the citiesFootnote 304, so they left rural farming to the locals: Syriacs, Georgians, Armenians, Maronites, and MuslimsFootnote 305. Those peasants helped in agricultural work, village management, and tax collection. Moreover, they cultivated the Condominium fields east of Tiberias and the villages of DamascusFootnote 306.

This treatment, or enlightened policy, as Raymond Smail called it, was a wise method adopted by the Franks with Muslim peasants in the provinces neighbouring their principalitiesFootnote 307. Therefore, Benjamin Kedar declared that the Franks, except for the head tax and agricultural taxes imposed on Muslims, did not change the conditions or methods of agriculture in Islamic villagesFootnote 308.

Lopez’s hypothesis about the agricultural development in Europe beginning in the tenth century and the ability of the Franks to diversify crops contradicted this supposeFootnote 309. Similarly, Claude Cahen referred to Antioch’s export of cotton to Genoa in 1140Footnote 310, and the Franks of Tripoli made efforts to increase the cultivation of cane, linen products, oils, and winesFootnote 311. Additionally, there were the polemics of Cahen himself, Joshua Prawer, Jean Richard, Meron Benvenisti, J. Riley-Smith, Jonathan Philips, Adrian Boas, David Jacoby, Christopher Tyerman, and Andrew Jotischky about the Franks’ interest in growing grains, cotton, fruits, legumes, olives, cane, and vines, as well as exploiting forests and extracting wax and honeyFootnote 312.

Arab sources supported those historians. Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī mentioned that Jabal al-Summāq was planted with cotton and sesameFootnote 313, which were not mentioned by the geographers who wrote about Jabal al-Summāq before the arrival of the Franks, suggesting that the Franks introduced them for their commercial valueFootnote 314. Likewise, when the Franks encouraged the farmers of Aʿzāz to cultivate its countryside, cotton was among its crops, until it was exported to Ceuta, according to Ibn SaʿīdFootnote 315. These examples demonstrated that the Franks intervened in the types of agriculture in the Islamic villages.

Islamic countryside and Crusader castles: The art of location and food strategy

The Frankish supremacy in the East was not secure. Distance and poor geographical communication dominated the reality of the Crusader principalities. For example, the distance between Edessa and Antioch was approximately 200 km, and Jerusalem was about 300 km, away from Antioch. The Crusader cities, except for Edessa, were confined to a narrow strip on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean. The eastern borders of these cities, overlooking a wide Islamic environment, were politically, militarily, and economically unstableFootnote 316. As Deschamps put it, the Frankish border points advanced or fell behind like chess piecesFootnote 317. This geopolitical situation encouraged Claude Cahen, Joshua Prawer, Raymond Smail, and Meron Benvenisti to argue that a somewhat isolationist reality had been imposed on the FranksFootnote 318.

It has been previously suggested that the Frankish expeditions against their Muslim neighbours in the Levant, before Zengids, were provocative to obtain profitable agreements, securing regular access to food supplies. This policy was parallel to the Franks building castles and fortresses in the Islamic countryside, helping them monitor crops and maintain their shares. Ibn al-ʿAdīm explained the method of building the countryside castle and highlighted the Franks’ keenness to store supplies there. He wrote: ‘In 1109 when Tancred controlled Tell ibn Ma’shar, overlooking Shaizar, he began to build a fortress, and made granaries’ Footnote 319. In the same context, William of Tyre explained that the purpose of the Franks’ control over Habis Jaldak was to guarantee them half of the crops of al-Sawâd region, ‘dividing the powers equally between the Christians and the infidels; the taxes and tribute were also equally divided between them Footnote 320‘. Arab sources confirmed the danger and threat of this fortress to the fields subject to the rulers of Damascus, east of TiberiasFootnote 321.

These castles contained cisterns and granaries to store taxes paid in-kind.Footnote 322 Some archaeologists believed that when the Franks allocated granaries in their castles, they adhered to the necessary standards to protect grains from the fluctuations of climate and the attacks of insects and rodentsFootnote 323.

It is noteworthy that both Muslim and Frankish rulers competed to build or demolish castles in areas of shared sovereignty. The Franks failed to build castles on the outskirts of al-Sawâd-Transjordan, on the outskirts of ShaizarFootnote 324, and in Aleppo countrysideFootnote 325, while their control over the Fortress of al-Athārib did not last, and they failed to build three fortresses in Ḥawrān, near Damascus. At the same time, the Franks prevented Ṭughtekīn from building a fortress in Wadi Musa (the Petra region) in 1107Footnote 326 and destroyed a fortress he built in Transjordan in 1121Footnote 327. This encouraged Prawer to confirm that these areas were devoid of Frankish fortificationsFootnote 328. The agreements of the thirteenth century between Muslims and the Franks may show that the Islamic side was refusing to construct any fortifications in areas under joint administrationFootnote 329.

However, the presence of the Frankish castles in Transjordan, the Islamic Tyre countryside – before 1124, the Islamic Ascalon countryside – before 1153, and Al-Ruj towards Aleppo, Krak towards Homs, Bāniyās towards Damascus added a kind of confusion to the analysis of this matter. It is clear that the Franks distinguished between two zones in building castles: Zone (A), which was very close to their domination, where the castle remained standing because it represented their first line of defence, and Zone (B), which was adjacent to Islamic cities, and the Franks were not allowed to build castles there.

This suggestion indicates two important points. First, borders indicated the end of the Frankish domination, or at least indicated the space within which the Franks were not allowed to build castles. It supports Ronnie Ellenblum’s argument that centres of power could be more important for maintaining control than linear bordersFootnote 330. It may also support Denys Pringle’s view that castles cannot defend a frontier but can help define the balance of powerFootnote 331. Second, the Frankish military pressure on the Islamic borders had led, in some way, to an agricultural benefit for the Islamic cities that turned to cultivating wastelands in their suburbs in order to compensate for the crops that the Franks were obtaining from areas under joint administration. For instance, Aleppo in 1110 and 1114Footnote 332 and Damascus in the 1120sFootnote 333 cultivated the surrounding wastelands.

In building castles, the Franks were motivated by the desire to possess a countryside that would guarantee them the provision of food supplies. In this context, Claude Cahen, Joshua Prawer, Paul Deschamps, Michel Balard, Karen Armstrong, and Steve Tibble were not right when they reduced the function of the Crusaders’ fortresses to the military defensive aspect, which was to protect their newly emerging citiesFootnote 334. Adrian Boas accepted this in his anatomical description of the castles of the Templers and the Hospitallers, stressing that their castles controlled and managed agricultural landsFootnote 335.

However, the presence of these castles brought into focus the Franks’ need for agricultural supplies during their intermittent campaigns. The Franks used to fight during the harvest season, in the spring and summerFootnote 336. Horses and mules typically require feed quantities of not less than 2.2 to 2.7 kg of barley and 4.5 to 6.8 kg of hay and water between 22.75 and 36.4 litres per day. If these mounts were left to graze, twenty horses would graze out an acre of medium-quality pasture per dayFootnote 337. The fighters ate meat, cheese, biscuits and wine, but when these goods were unavailable, they relied on large quantities of bread. Consequently, their need for wheat and barley was essentialFootnote 338.

On this basis, an army of 15,000 would need at least 288,400 kg of provisions for two or three weeks, excluding water, wine, oil, cheese, fish, lard, and animal feedFootnote 339. The Frankish army besieging Aleppo in 1124 was about the same numberFootnote 340; it suffered throughout the winter months (October-January) as badly as the people of Aleppo due to the lack of agricultural supplies, especially wheat and barleyFootnote 341. Similarly, during the siege of Damascus in 1129, the Frankish army consisted of 2,000 knights and more than ten thousand infantries who suffered from the same conditions. According to Tibble and Morton, roads became more difficult, fodder for horses became scarcer, and supporting a large army in enemy territory became a logistical nightmareFootnote 342.

These two sieges failed because of winter and a lack of agricultural supplies. However, King Baldwin II – leader of both sieges – wanted to have lands for settlers and colonial militia to farm and fiefs to support the ever-growing numbers of knights needed to defend the bordersFootnote 343. This was confirmed by Muhammad K. Ali, saying: ‘The Franks were keen to seize the villages of Aleppo, Al Beqaa, Ḥawrān, Al-Sawâd, and Balqāʾa to obtain their crops because most of the Palestinian villages were battlefields that did not feed their armies’Footnote 344. This view may be supported by Hans Mayer’s assertion that the construction of Frankish castles was accompanied by agricultural settlement expansionFootnote 345. In the same context, Ronnie Ellenblum believed that some castles were symbols of power and the nuclei of new settlementsFootnote 346. He confirmed that some Frankish castles were built to supervise the villages and crops and to activate the markets. This was kept pace with the growing agricultural movement and Frankish settlement in the LevantFootnote 347. Ellenblum’s opinion was based on Raymond Smail’s functional analysis of castles and fortresses, where he stated that it was not only military, but one of its tasks was to monitor Muslim villages and farmers and to ensure tax collection, citing castles built for this purpose during the first settlement periodFootnote 348. Accordingly, the Frankish castles represented bridgeheads that ensured the arrival of agricultural supplies to their citiesFootnote 349.

A good example of this strategy was in the citadel of Safed, which guarded the Bāniyās outskirts, overlooked Lake Tiberias, and controlled a wide meadow abundant with agricultural supplies. Although the best stories about this castle came from sources in the thirteenth century, their content was not far from the reality of the twelfth century. It was reported that the villages affiliated with the Castle of Safed amounted to two hundred and sixty villages with ten thousand people, whose agriculture included grains, vegetables, figs, pomegranates, and vines (see Table 4). The castle’s livestock grazing and fishing were widespreadFootnote 350. A note to Al-Umari revealed that crops were brought from Damascus to SafedFootnote 351. Although Meron Benvenisti believed there was an exaggeration in the number of villages affiliated with this castle, he did not mind the presence of a Frankish settlement and widespread agriculture until the 1180sFootnote 352. The castle had bakeries, twelve grain mills, wells, and cisterns. Its warehouses accommodated twelve thousand mule loads of wheat, barley, and other foods annuallyFootnote 353. This made it an ideal Frankish settlement and a vital storehouse, supplying Jerusalem with foodFootnote 354.

Table 4. The important crops that the Kingdom of Jerusalem benefited from the Damascus rural suburbs

The success of the Franks of Jerusalem in building Toron in 1104 was no less than their success in Safed. William of Tyre and Jacob of Vitry praised the countryside near Toron Castle and its fertile lands, abundant production of vines and fruit, and, consequently, its abundant supplies for the population of the KingdomFootnote 355. Similar to Toron was the castle of Chateau Neuf, overlooking Bāniyās (built circa 1107), which Ibn Jubayr praised and noted that Muslims and Franks shared its crops and pastures fairlyFootnote 356. Similar to these two castles was Subeibe Castle, which was owned by the Franks in 1129. It was on top of Bāniyās countryside, overlooking the villages and fields southwest of DamascusFootnote 357. The Franks fortified this castle well and filled it with food storesFootnote 358. Here, it is worth reconsidering Müller-Weiner’s statement that Al-Subeibe, along with the Safed castle and the Toron castle, protected the northern borders of the Kingdom of JerusalemFootnote 359. It is likely that the function of these three castles, besides Chateau-Neuf Castle, was not military, as much as it was an attempt to gain control over the Bāniyās countryside, to ensure the arrival of the necessary agricultural supplies to the Kingdom and to provide a stable income through taxes imposed on commercial goodsFootnote 360.

However, some scholars rejected this argument for building Crusader castles. For example, Michel Fulton ignored the importance of the countryside of Montreal castle, which Baldwin I built in 1115 on the eastern side of Wadi Araba, south of the Dead SeaFootnote 361. He reported that its construction aimed to control the trade route between Syria and Egypt and monitor the passage of Muslim pilgrim caravansFootnote 362. He was undoubtedly influenced by Albert of Aachen’s accountFootnote 363 and the scholars who supported him, such as René Grousset, Claude Cahen, and Jonathan Philips, about the desire of the Kingdom of Jerusalem to control trade beyond the Dead SeaFootnote 364. Fulton may also have been influenced by Jacques de Vitry Footnote 365and the scholars who supported him, such as Rey, Conder, Prutz, DeschampsFootnote 366, Prawer, Mayer, and Tibble, who emphasised the strategic importance of Montreal and Karak castlesFootnote 367. In contrast, William of Tyre asserted that Montreal castle protected the countryside, extending to the east and north, and was wealthy by producing essential goods for the Kingdom of Jerusalem’s population, such as wheat, wine, and oilFootnote 368. Al-Idrisi confirmed this, adding almond, fig, and pomegranateFootnote 369. Nicholas Morton summed it up by saying Montreal was used as a staging post, supply base, and place of retreatFootnote 370. The remains of three Frankish mills affiliated with the castle assured the abundance of grain arriving at Montreal castleFootnote 371. Oliver of Paderborn emphasised the logistical importance of the two castles to Jerusalem, saying: ‘Whoever holds Montreal and Karak castles in his power can very seriously injure Jerusalem with her fields and vineyards when he wishesFootnote 372’. According to sources, the Franks threatened the trade line between Cairo and Damascus, passing the Jordan River, on several occasions prior to the construction of Montreal and KarakFootnote 373. Therefore, the two castles did not only stand within the framework of the commercial space suggested by these historians but also highlight its logistical importance in supplying Jerusalem with vital supplies. They were also administrative centres for the collection of agricultural and caravan taxesFootnote 374. Thus, it encouraged Baldwin I to rebuild another nearby castle, al-Wu’ayra, in 1116 on the head of Wādī Mūsā area, which was full of wheat, pastures and various fruit trees, for the same purposeFootnote 375. This prompted Micaela Sinibaldi to say that the Petra region not only represented an important agricultural source for the Franks but was also a settlement outpostFootnote 376.

The Franks established customs ports next to countryside castles. For example, a customs port was established near Toron for taxing goods in the amount of 1/24 of the value of the goods passingFootnote 377. Like Toron, the castle of Mons Glavianus was established by King Baldwin II in October 1125, six miles from Beirut, to control the agricultural valleys extending to this city and to facilitate the collection of taxes from its villages as far as Bāniyās Footnote 378.

The Franks controlled forts located on trade routes, such as the Al-Qubba fortress, southwest of Aleppo, through which they collected huge taxes from the trade convoys passing between Aleppo and the southern part of the LevantFootnote 379. In addition, they benefited from their castles in extending trade lines between their coastal cities and Islamic cities such as Mosul, Damascus, and AleppoFootnote 380. For example, when Tancred sought to build Tell Ma’shar castle (Sarc), he intended to secure a road between it and Apamea and the castle of Kasrael, all the way to the port of JablehFootnote 381. This account confirmed Prawer’s suggestion that the Franks wanted their cities to be more like transit stations, receiving Islamic goods and sending them to EuropeFootnote 382.

In sum, Frankish castles were built for military purposes but served as economic bases at the same time. They ensured the arrival of agricultural supplies to the Crusader cities, on the one hand, and provided a fixed outlet for receiving commercial goods and collecting taxes, on the other.

Conclusion

Contrary to the old stereotype that the Frankish community in the Levant relied mainly on food supplies coming from Western Europe, this study attempts to prove that the Islamic countryside was a major warehouse for the Franks in the Levant throughout the first half of the twelfth century, supplying them with grains and various necessary crops directly connected to the markets of the Frankish cities. Their flow triggered the development of the markets of these cities, and the opposite led to their poverty, as happened on several occasions; some of the Crusader cities were subjected to famine when the supplies of the Islamic countryside were interrupted, as happened in Jerusalem in 1154 and in Antioch in 1164. Therefore, the Islamic countryside was not a source of hostility until the Zengids built their united state.

The supplies carried by European commercial cities to the Crusader cities in the Levant were very scarce in the first half of the twelfth century compared to the increasing requirements of the residents of these cities. Italian investments in the Levant did not become active until the 1130s, after the Zengids appeared, whose efforts to unite the Islamic forces led to limiting or cutting off the supplies of the Islamic countryside from the Franks.

The Frankish attacks on Islamic cities were not aimed at sabotage as much as they were a means of pressuring the Muslim rulers to conclude adequate agreements, securing the Franks a permanent share of the crops of the Islamic countryside. These agreements were among the basics of the economy of the Crusader cities, and their benefits went beyond the military aspect to being economic necessities for living, as they allowed the Franks to secure their vital supplies for decades. Accordingly, the Franks did not build their castles for military purposes only, as much as they aimed to perpetuate their agreements with the Muslims and preserve their share of their crops.