Introduction

On 16th July 1864, a miner named John Terrell lost sight of his nine-year-old daughter. They had been searching for some stray goats in the forest near the Blackwood goldfields, ninety kilometres northwest of Melbourne, when the little girl wandered from her father’s view. John Terrell returned home on this wet winter’s day, and when he realised that his daughter was not there waiting for him several newspapers reported that ‘the anxious father scoured the bush in every direction. Darkness, wet, and the bitter coldness of the night intensified the grief of the distracted parent.’Footnote 1 Before long, ‘[b]eacon fires were lighted in several directions’, and police and neighbours formed ‘relief parties’ to look for the girl who went unnamed in the newspapers’ coverage of the event. The papers said of those who searched for Terrell’s daughter that ‘one and all proceeded on a tour of exploration, as exciting as it was humane. Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, [and] Thursday passed away in succession, with little remission in the labour of love; but no joyous tidings of the missing had arrived.’ Finally, on 22nd July 1864, six days after her disappearance, the search parties that were splayed throughout the forest had their ‘attention arrested by a faint cooie’. Another gold digger, Henry Allen, had found Terrell’s daughter. Allen took ‘off his coat, wrapped it around the girl, and bore her in triumph on his back. The news soon spread, and it is … superfluous to add that all present participated … in the pleasure manifested by the delighted parents’ at having found the young girl alive.

This type of ‘episode of lost and found’, as The Argus called it, has been overlooked by scholars, who have largely concentrated on those children who never returned when assessing the child-lost-in-the-bush phenomenon in Australia. Many, including Peter Pierce, Elspeth Tilley and Terrie Waddell, have focused their analyses on fictional representations of the figure of the child lost in the bush.Footnote 2 Kim Torney’s landmark study focused on real-life cases, and she recognised that the searches for lost children were remarkably similar in structure, clearly part of how the emergent ‘moral centre of bush life and values’ was articulated; and the searches became inscribed in ‘cultural memory’.Footnote 3 Contrary to the focus on the children who never came back, the three Duff children, who became lost near Horsham a few weeks after Terrell’s daughter, attracted huge search parties before being found alive nine days later, and this story resounded more than any other. Upon rescue, the Duffs stepped into myriad fictional representations in literature, artworks, and eventually primary school readers.

The story of the Duff children became so prominent because it reflected the experiences of many of those who participated in successful searches for children. Peter Pierce observes of the Duffs, ‘[t]he most famous of all stories of lost children in colonial Australia might be regarded as untypical of them, for it had a happy outcome.’Footnote 4 But this statement was far truer of literature than it was of embodied experiences of looking for lost children, because most of the time search parties found the lost child or the child came home. As such, this article redefines the child-lost-in-the-bush archive to include cases in which the children returned alive and it focuses on the concrete, communal behaviours, from which the vast, well-studied mass of literature about children lost in the Australian bush has sprung.

Examination of hundreds of newspaper articles and dozens of coronial inquests from goldrush Victoria (and beyond) has revealed that, when communities searched for bush-lost children, some elements of communal behaviour were common to (virtually) all incidents. Regardless of the searches’ outcomes, large cross-sections of communities would cease normal activities, gather together and search anxiously and systematically for the lost child or children. On a search’s completion, participants often experienced powerful catharsis, either in the form of joy or grief, depending on the outcome. At least since the onset of modernity, the treatment of children has been an important part of how anglophone communities have defined their moral standards and identities.Footnote 5 Accordingly, using a Neo-Durkheimian lens, this article considers the figure of the bush-lost child as a représentation collective, a site of ‘collective memories’, which contains ‘publicly available symbols and meanings about the past’.Footnote 6 Through this lens, it will emerge that in new communities, people connected with one another through a shared relation with the figure of the lost child.

Although the culture of community-wide searches may appear to have simply been a natural response to a community member going missing in the bush, as Kim Torney argues, the dimensions of the Australian phenomenon of seeking bush-lost children was unmatched in other settler colonies in the nineteenth century.Footnote 7 Further, community responses to children becoming lost in the bush contrasted starkly with when adult men went missing in this period. Contradicting scholars like Peter Pierce and Kim Torney, Elspeth Tilley has argued that lost children were but one of many iterations of the broader literary phenomenon of ‘whiteness vanishing’ on the frontier and just one expression of the anxiety experienced by white settlers in a new land.Footnote 8 But, as with some other observations about the literary traditions associated with lost children, this perspective ignores the particularity of actual historical responses to children going missing. If one shifts their focus from famous or fictional bush-lost adult males to actual historical cases when men went missing, it emerges that it was common for police and trackers – and no one else – to look for lost men. One Polish man in 1866, for example, was lost in the bush for a number of days and cut his wrists to drink his own blood, in order to quench his thirst, before anybody thought to look for him.Footnote 9 His case was especially gruesome, but it was far from unique.Footnote 10 In contrast, when a child went missing – any child – they immediately became important to the community and were often reported on across the Australian colonies simply for becoming lost.

The paradigm of communal searches for lost children really became embedded in the social unconscious of the Australian colonies from the 1860s.Footnote 11 It especially took hold in new communities of settlers in places like the Victorian goldfields, with diverse ethnic and religious identities and often poor social cohesion. That is, communities in which it was not readily apparent how people would come together to produce lasting, successful communal life as the goldrush waned. When children became lost in the bush, diverse groups found common ground, regardless of whether they shared a native language, religious affiliation or national identity. In order for any human society to successfully reproduce itself, it has to find ways of caring for their vulnerable young children. Many settlers also sought to make a home in a land that, at least initially, felt alien to them. So, sentiment for children lost in the bush resounded cross-culturally, and in these moments the lost child formed a juncture at which communal feeling could find expression. From the 1860s, the ‘rite’ of the search for children lost in the bush emerged as one of many modalities that gave communities what they needed to effectively bind together.Footnote 12

The first section of this article defines the key terms of ‘social cohesion’, ‘rite’ and ‘moral community’, drawn from the sociology and anthropology of ritual. It then describes the settlement context of the goldrushes, presenting the problematics that nascent communities faced because they lacked social cohesion. The second section sketches out the elements of the secular rite of the bush searches, namely the gathering of a diverse cross-section of the community, the articulation of a shared relation with the lost child, economic sacrifice for the child and the sharing of heightened affective states by community members. This article asserts that, in such moments, settlers found and reinscribed common moral ground through the figure of the lost child. The brief, final section explores the narrative marginalisation of Aboriginal trackers, who were central to so many searches. In the end, the expression of new settlers’ communal values, through coming together around white, lost children, co-existed with the exclusion – physical and discursive – of Aboriginal people from a central place in settler society.

Community, social cohesion and ritual in 1850s Victoria

Over time, searches for lost children increasingly assumed the structured, repeatable form of a ritual, through which members would reinscribe a common morality. In this article, the term ‘ritual’ and ‘rite’ are used in their anthropological sense.Footnote 13 Emile Durkheim claims in Elementary Forms of Religious Life that ‘there is something eternal in religion’, which is to say that the social functions performed by religious activity would still be important, even in a theologically non-religious society.Footnote 14 He created a secular definition of religion as a ‘moral community’, a concept that has since become in many ways analogous with Benedict Anderson’s ‘imagined community’.Footnote 15 One of the ways in which a moral community produces and reproduces social cohesion is through ritual – through community members gathering together, suspending economic activity, which belongs instead to the world of the ‘profane’, and engaging in concrete action around a sacred object or person, which is ‘set apart and forbidden’.Footnote 16 For Durkheim, it is not necessarily a deity or identifiable institutional organisation that makes a moral community, but ‘a society whose members are united by the fact that they think in the same way with regard to the sacred world and its relation with the profane world, and the fact that they translate these common beliefs into common practices’.Footnote 17 In this instance, it was the common belief in the vulnerability of children and that protecting a lost child was a community’s concern, not just a family’s; and this shared way of thinking became translated into the rite of the bush search when a child went missing. Over the course of the 1860s, searches for lost children would not only develop into a ritual that reflected existing beliefs, though. It would also assume culturally productive dimensions, as can be seen through the distinctive place of the child-lost-in-the-bush trope in Australian fiction, which has been well established in the academic literature.Footnote 18

Beyond the bare fact that myriad images and stories of lost children were produced for communal consumption is, perhaps, something more fundamental. As ore deposits ran dry in new Victorian communities, the settlers needed to establish social cohesion for their towns to continue to exist and gradually outgrow their goldrush origins. Social cohesion is ‘the willingness of members of a society to cooperate with each other in order to survive and prosper’.Footnote 19 Stories – and experiences – of communities banding together to search for lost children established, from the 1850s and 1860s, the public expectation that each adult would join a search for their neighbour’s children and vice versa. As such, in new, multi-ethnic, multi-denominational communities in Australia, the very prospect of searching for lost children embodied the ‘cooperation’ and shared efforts for ‘survival’ and ‘prosperity’ that define social cohesion. Before describing the symptoms of lacking social cohesion in the Victorian goldfields in this period, it is first necessary to define ‘the bush’, the setting of so many searches for lost children.

The nebulous concept of the bush refers to the Australian wilderness. This one signifier could refer to any number of different settings. The bush was and is an odd, discursive monolith, which in the nineteenth century enabled the many, local stories that became disseminated through developments in print media to be imagined as a singular and coherent phenomenon throughout the continent’s many landscapes. A newspaper story about a child lost in the semi-arid plains near the Hundred of Goyder and another about a child lost in the cold, temperate rainforests of southern Tasmania would both be titled ‘Lost in the Bush’, for example. Even in the colony of Victoria, varied landscapes from the dusty ‘scrub’ of the Mallee to the sub-alpine forest surrounding the gold town of Walhalla were both glossed as ‘bush’. While this versatile conception of the bush would ultimately render the bush-search trope more resounding when disseminated in print, the context in which this trope came to thrive in some ways determined the form that it assumed. In nascent towns, where community members had come from different parts of the globe and were unsure of what they had in common with their neighbour, they rallied around the figure of the lost child as a shared touchstone of what was most important.

Throughout the nineteenth century, frequently recurring global migration events were stimulated by ongoing discoveries of gold deposits; populations shifted en masse as they followed hopes of fortune.Footnote 20 In 1851, gold was discovered in Clunes, near Ballarat, and Mount Alexander, at Castlemaine. Finds in Bendigo and Ballarat proper soon followed. Further deposits were quickly uncovered across the Victorian landscape, and more than thirty towns grew around sites of extraction.Footnote 21 Official figures vary, but during the second half of the nineteenth century, the colony produced almost 1,900 tonnes of gold – miners in Victoria removed almost 95,000 kilograms of gold in 1856 alone.Footnote 22 The labour that the goldrush attracted to Victoria demanded the genesis of new settlements, made up of populations from diverse communities of origin.

Following European settlement from the 1830s, the colony’s population climbed at a modest rate, having reached 77,000 by the beginning of the 1850s. By the end of the following decade, the figures jumped sharply to more than 200,000, of which just 27,000 were women and 35,000 children. The first wave of diggers to the goldfields was overwhelmingly male but by 1871 children under 15 constituted more than half of the population of Bendigo and 43 per cent of Ballarat.Footnote 23 The total population of the main goldfield regions was 145,000 and during the 1850s communities transformed to become more than just gold towns. Employment diversified and professions, business and skilled trades eclipsed mining to become the main occupations for male workers.Footnote 24

Hundreds of thousands of Christians from England, Scotland, Ireland, Cornwall and to a lesser extent the Continent and Americas travelled to the diggings. In 1850 Anglicans comprised 48 per cent of the population.Footnote 25 Catholics made up 23 per cent and the Presbyterians 16 per cent, and these figures remained virtually unchanged for the next two decades. Over the same period, poverty and a lack of quality clergy triggered the Anglican population to drop in numbers from 48 to 35 per cent, while a concerted revival campaign by the Methodists saw their representation rise from 7 to 12 per cent.Footnote 26 Prior to the goldrush, non-Christian groups were mostly represented by Aboriginal people. Then, numbers of Chinese Buddhists and ‘Afghan’ Muslims and Sikhs arrived in the 1850s to take advantage of the golden opportunities.Footnote 27 Up to 20 per cent of the Victorian male population between 1850 and 1870 were Chinese men.Footnote 28 As Weston Bate observes, many Britons arriving during the goldrush were experiencing interactions with other ethnicities for the first time.Footnote 29 Indeed, they were not only interacting with them, but forming part of the same community.

The Victorian goldfields primarily began settled existence as a transformed environment experiencing frontier transitions from pastoral exploitation to mining. Scholars of the goldfields describe the diggings culture as rebellious, enterprising, and ‘new’.Footnote 30 Mining towns were rough, improvised places, formed as temporary sites to service miners who meant to remain only long enough to set up camp and win their fortunes, and just as quickly return to their homes with pockets full. But in these young towns, planning and infrastructure remained low priorities.Footnote 31 The settlers’ desire for permanence soon enough overcame the sojourners’ push for maximum resource extraction. In an age of heightened senses of nationalism and sectarianism, the assemblage of diverse ethnic, denominational and previous national identities within unique communities called for novel processes of establishing social cohesion.

In the burgeoning townships of Victoria, disquieting markers of a lack in community harmony were offset by often-unconscious efforts to generate closeness. In terms of labour relations, racism and shifting ethnic tensions coexisted with what Keir Reeves calls ‘moments of cultural and economic cooperation’, as miners formed partnerships for protection and companionship.Footnote 32 However, the bleakness of goldfields life was too much for some. A 2009 study of Bendigo in this period reveals that a relatively high proportion of single men – the demographic most actively involved in the searches for bush-lost children – committed suicide.Footnote 33 Those men who were not well integrated into their new communities were most at risk. Frontier traveller and prolific biographer William Howitt wrote of a goldfields community in 1853 in which ‘scarcely a night has passed without the most awful cries of murder; and robberies are as certain as the night’.Footnote 34 There were high rates of murder, assault, rape, and theft. In short, goldfield societies demanded the innovation of approaches to building social cohesion, which would reduce the prevalence of crime and other social pathologies; and social cohesion is what such communities derived from collective searches for lost children.

The very fact that so many settlers were often moved to search for lost children reveals something of the complexity of belonging in an emerging settler colony. Peter Pierce argues that European anxieties about being lost in the Australian bush were rooted in a sense of alienation, while Joanne Faulkner points out the opposite, that ‘children became lost because they, and often their family, felt quite at home in the bush’.Footnote 35 Of course, both statements contain truth – and it is from this very tension, between settlement and alienation, that the bush searches emerged as a ‘rite’ in frontier towns, which were in the throes of finding ways to get along and belong together as a community.

Gathering together

From the period when the lost child trope really came to life over the course of the late 1850s and the 1860s, virtually every time a child went missing adults would gather in sufficient numbers for it to be a veritable community event. In the famous instance of Daylesford, for example, in 1867, when the two Graham brothers and Arthur Burman went missing on a winter’s day, the local paper called for volunteers to search for the children. On the Monday, police and neighbours searched into the evening, and on the Tuesday ‘between two and three hundred citizens and police … again examined the country’. People from beyond the township, such as the men of the nearby ‘Corinella Mine, the Telegraph saw-mills, and Clarke’s Mill, and nearly all the splitters in the forest’ stopped working in their hundreds in order to comb the bushland.Footnote 36 Gathering on the second night at the Bleackley Hotel, the townspeople decided ‘with one voice’ that ‘business should be utterly suspended’.Footnote 37 According to The Perth Gazette and West Australian Times, ‘altogether 600 or 700 persons joined in the search’ – a huge proportion of this community, which had just a few thousand residents.Footnote 38 As the days passed, the searches remained unsuccessful. In spite of failure to find the children, Daylesford remained closed to all business, except that of looking for the three lost youths, and five hundred people or more went out together and scoured the bush right through the week with some community searchers going out over a month after the boys’ disappearance.

The Daylesford community was especially ethnically diverse. One resident in 1857 wrote to her sister in Scotland to say ‘You ask me “what like are the people around you”? They are just a mixture of all nations. My nearest neighbours are Irish, the next are English and we are Scotch.’Footnote 39 The region had also attracted significant Italian, Swiss and Chinese populations, as well as enough French, German, Welsh and American expatriates to have justified naming features of the landscape after these nationalities. When community members mobilised, it was from across these various ethnic, linguistic and denominational groups.

Although the sources usually fail to explicitly state the ethnic composition of search parties, they sometimes reveal the searches’ multi-ethnic character implicitly. Most frequently, search party members were English, Irish, Scottish, Welsh or Aboriginal; however, some newspapers and inquests note the participation of people with Chinese or other European origins. A highly narrativised rendition of the story of a boy named Victor, who became lost near Mildura in 1893, noted that one of the searchers, ‘Morré, who is of French extraction … replied “E vent up ze bank wiz a girl”.’Footnote 40 Similarly, in 1889, The Age reported that ‘hundreds of people’ had scoured the bush near Whipstick Gully in eastern Victoria for an eight-year-old boy named James Greed, and it was ‘a party of Italians’ who lived locally that picked up the sound of Greed crying.Footnote 41 When a toddler went missing near Weaner’s Flat in 1872, the Adelaide Observer noted that few British settlers south of the station joined the search for him, ‘but the Germans around used great exertions, and earned well-merited commendation’.Footnote 42 In October of 1867, Mount Gambier’s Border Watch reported that, when the four-year-old Buninyong girl Jessie McIntosh became lost in the bush near her family home, ‘all the township turned out’ for the search – and ‘some Chinamen’ reported that they were the last to catch sight of her.Footnote 43 As can be seen through these cases, Australian sources did sometimes indicate the ethnicities of those who searched in one way or another, but usually such references are made in passing. More frequently, the sources fail to identify the backgrounds of search party members. Yet, this state of affairs is hardly surprising, as the searchers’ diversity was not considered a cause célèbre; instead, the sources tend to focus on the children’s vulnerability and the searchers’ togetherness.

In this context, the relative paucity of sources identifying ethnic diversity within search groups seems to indicate that multi-ethnic cross-sections of the community commonly searched for lost children together, that such occurrences did not warrant comment and that shared experience of searching for lost children was what mattered to communities, not the differences among those who contributed. When the Portland Guardian proudly listed the names of over a dozen community members who had ‘billeted together’ while searching for a two-year-old boy and ‘raised a great shout of joy’ upon finding him, the newspaper did not feel the need to observe that these searchers had Italian, Chinese, Irish, English and Scottish names (Pedrazzi, Pung, Nulty, Bailey, Cochrane, McPhee, Jarrett, and others).Footnote 44 Most frequently, it is through the names mentioned in the sources that the ethnicity of searchers can be divined. In Victoria, a Swiss dairyman named Agostino Vosti arrived in March 1855, aboard the Lucie, as one of many northern Italian and Swiss passengers escaping poverty.Footnote 45 Twelve years later, near Myer’s Flat, Vosti would be the one to find the body of the three-year-old miner’s son, Thomas Mulhall, whom inquest records would describe as ‘the lost child for whom so many people had been searching for days past’.Footnote 46 In 1882, when four-year-old Howard Emmett disappeared at Sheepwash, near Bendigo, the search – led by a mounted constable McGuire – began from the site where a French man named L’Huillior had heard the child crying.Footnote 47 A farmer and viognier, Remy Felix L’Huillier had emigrated to Australia in 1853, settling with his family on a small selection near the station where Emmett would disappear.Footnote 48 In the above cases, including those referred to in the previous paragraph, the records do not indicate that such participation was irregular; it appears that bush-lost children held significance for community members regardless of their ethnicities, and that search parties were commonly constituted by diverse sets of people.

Most of the time, the participation of multi-ethnic community members emerges as a strong likelihood and escapes explicit description in the sources, which usually focus on the children’s hardship and the community’s shared experiences. In 1856, for example, when a four-year-old boy went missing near Cheetham Flats, a little way west of the Blue Mountains, forty horsemen, a flock of sheep and numerous women searched ‘in every direction’ for the lost boy. Before long, ‘the whole neighbourhood was aroused’ and incited to search for the child, whom community members found after three nights; and the searchers, ‘raised a shout which the [people in the] wood re-echoed in every gladness’.Footnote 49 The population around the Blue Mountains was diverse in the 1850s, due to the goldrush, so it seems safe to assume that ‘the whole neighbourhood’ would have involved a diverse cohort of searchers, although the sources do not explicitly state as much. Perhaps nowhere in Victorian was more diverse than the multi-cultural city of Melbourne, though. There, in 1858, an eight-year-old boy named Louis Vieusseux went missing at Fern Gully, on Melbourne’s outskirts. All the adults present immediately embarked on a search, and a significant, but unspecified, number scoured the bush in ‘cordons’ for three weeks, with Aboriginal trackers and settler men on horseback.Footnote 50 In this instance, it was less the search that reveals communal sentiment, than the stir of public interest in Melbourne which the search for Louis caused – concern for this lost child became everyone’s business before long, and his tragic fate was felt in homes throughout Victoria’s capital.Footnote 51

Yet, with the searches for lost children, urban centres like Melbourne resided on the peripheries, while rural communities took centre stage. So often, when a child went missing from a remote digging or selection, a significant proportion of the community’s fiscally productive members mobilised and engaged with that ‘labour of love’, referred to in the Terrell case – but more than this, cases where children became lost in rural areas would resound the most across the nation, as with the Daylesford and Duff children, for example.

Public morality

Recall that the act of searching for John Terrell’s daughter, mentioned at the beginning of this article, was described as ‘as exciting as it was humane’. Both the ‘humane’ element of these events and the associated ‘excitement’ were significant. In the searches for these children, the lost child often emerged as a figure at the centre of what Durkheim called a ‘moral community’, which is to say that the limits of this ‘moral community’ were, of course, articulated by those who were considered not to have had the right disposition towards lost children. For instance, in 1858 when nine-year-old Norah Hinds disappeared in Myer’s Flat, she was found safe by police the next afternoon. In the interim, publicans and bullock drivers had sighted the girl, but their failure to offer assistance ensured they quickly became subjects of public disapprobation.Footnote 52 The local newspaper felt that ‘the conduct of any persons who saw a child of tender years like this wandering about alone, without endeavouring to make some provision for her safety is censurable in the highest degree’.Footnote 53 Likewise when Thomas Mulhall disappeared he was later sighted crying by the road, and rather than grant Thomas’s request to be taken home, a man named Davis instead waved him off to a house further down the way.Footnote 54 Inquest jurors later found Davis much to blame for Mulhall wandering into the scrub alone, where he died from thirst, exhaustion and exposure.Footnote 55 In the case of the toddler Robert Jackson, an inquest jury castigated the woman originally charged with the supervision of Jackson, having failed to take the proper care she had promised the mother.Footnote 56 Thus, where newly formed expectations of socially cohesive behaviour failed to be met, transgressors were singled out for public condemnation.

Information about the developing, normative relation with lost children, that is, people’s understanding about their expected roles, was becoming more widely known. The 1867 Daylesford case established an early pattern for reporting on children’s disappearance in the bush and conveyed a paradigm for communities to follow when their turn arrived. One Kilmore paper proclaimed the disappearance – and later rediscovery – of the three-year-old son of a wood splitter at Mount Macedon, saying that ‘no sooner has the excitement about the lost Daylesford children subsided … than we are startled in our own locality with the tidings of a child being lost in the bush.’Footnote 57 Soon after, a Melbourne magazine announced Jessie McIntosh’s disappearance in Buninyong with ‘we have an exciting story about another lost child’. The same magazine headlined a Warrnambool case a year later as ‘another child lost in the bush’.Footnote 58 In the late 1860s, when searching for a lost child, communities would frequently position their experience with relation to other well-known stories, like that of Daylesford or the Duffs.

By the early 1870s, communities better recognised their responsibilities through such narratives. On Christmas Day, 1872, a little boy named David Williams spent ‘two nights and days during which he was lost’ in the forests near the Stawell diggings. Once Williams returned safely home, the paper wrote, ‘words could hardly describe the feelings of gratitude on the part of his parents … as well as to all those who so humanely took part in the search and persevered until the boy was found’. The author concluded the newspaper article by pointing out that Williams demonstrated a

never-failing hope of getting home, [which] if we remember right, was experienced by the Duff children when lost for so many days, and never deserted them, even in their famished state. It ought to prevent those engaged in searching for lost children from ever relaxing their efforts till the lost one is found, dead or alive.Footnote 59

Evidently, by this point, the searches had become prescriptive, and circulated as an element of cultural memory, with this journalist looking both to the past and future of this increasingly ritualised activity.

Economic sacrifice and the sacralisation of childhood

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the emerging ritual of the searches often involved different forms of economic sacrifice for lost children, and these practices reflected Australia’s shifting meanings of childhood. Across the Western world in this period, childhood was in the throes of becoming redefined, attaining greater distanciation from adulthood at the discursive level.Footnote 60 Over the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, children in the Western world were largely expunged from the workforce.Footnote 61 Although children in Australia did not participate in industrial labour at the rates seen in other Western societies, from the 1860s onward, Australian parliamentarians, activists and concerned citizens still fretted over the pockets of industry that did employ significant cohorts of children.Footnote 62 Over this period, schooling became compulsory and universal in Australia. Victoria’s Education Act passed in 1872 and other colonies followed suit in the subsequent decades.Footnote 63 Accordingly, as Hugh Cunningham argues, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, children were simultaneously ejected from the adult sphere of work and entered into the separate domain of the schools – a domain distinctive to childhood.Footnote 64 As a result, childhood and adulthood became more sharply distinguished categories over this period.

As constructions of childhood transformed throughout Australia, adults increasingly made fiscal sacrifices for children, but the Australian situation differed somewhat with that of Britain and the United States. In her landmark study of these latter societies, Viviana Zelizer asserts that children’s exclusion from paid labour occurred as childhood became gradually ‘sacralised’ over the late nineteenth century. As public sentiment increasingly rejected the idea of mixing ‘sacred’ children with the ‘profane’ world of industrial labour, adults also articulated their shifting sentiment towards children through alternative means, including engagement in ‘ritual’ uses of money in ways that reaffirmed children’s augmented social value. For example, in Britain and the United States, parents paid ever-higher premiums and more frequently took out industrial insurance policies on their children’s lives between the 1870s and the 1930s. Over the same period, children became worth less and less as economic actors. As such, parents were irrational to spend more and more money to insure their children’s economic contributions, but they did anyway. To paraphrase Zelizer, over the period when it became normal for children to be economically useless, childhood became resignified as ‘emotionally priceless’, and parents spent more money on children who were bringing in less money than previous generations of youth.Footnote 65 However, while it is common for Australian scholars to casually cite Zelizer’s study when making the point that Australian childhood became more distinguished from adulthood during the late nineteenth century, the Australian case differs from Zelizer’s paradigm in some significant ways.

Australian child labour conditions were something of an anomaly, and there was no thriving children’s industrial insurance industry in the Australian colonies during the nineteenth century. The children’s life insurance industry failed, substantively because communities distributed throughout the Australian bush made sales difficult.Footnote 66 Additionally, as alluded to above, and as Bradley Bowden’s work has established, Australian children did not participate in the paid labour force at rates comparable with Zelizer’s case studies of Britain and the United States.Footnote 67 Furthermore, Australian children’s gradual exit from the workforce from the late nineteenth century was not accompanied by the levels of intense and impassioned public dialogue that existed in other Western societies; and so children’s roles in Australian society were not reinscribed through the very process of public debate in the same way as they were overseas.Footnote 68 Australia has its own, particular history of changing meanings of childhood, a definitive account of which is beyond the scope of this article. The point remains, however, that Australian social practices, which involved making economic sacrifices for bush-lost children, formed part of Australia’s distinctive history of changing meanings of childhood in this period.

Especially from the 1860s, goldfields community members would increasingly make economic sacrifices for lost children. For example, people would sometimes offer their own money as reward for finding a lost child, even if they did not have a personal connection to that child. In a letter to the editor in 1864, a man named Thomas Robinson wrote in praise of a ‘heroic’ girl, eight years old, who went missing from Ballarat.Footnote 69 He enclosed one pound and encouraged others to do so as well. The more high-profile Jane Duff was twice provided with lump sums worth hundreds of pounds in her lifetime, donated by community members for her bravery when lost as a child; and, similarly, benefactors would establish a scholarship to commemorate the Daylesford boys at their local school.Footnote 70 This way of contributing funds to a lost-and-found child – or, indeed, children who perished – represented what Zelizer has called ‘a ritual use of money’.Footnote 71 This type of expenditure can be considered an alternate mode of articulating the gradual ‘sacralisation’ of childhood. Such donations were like libations of funds, which community members would ‘tip out’ in the name of the lost child.

In addition to these explicit sacrifices, communities committed far greater economic resources to lost children indirectly, through forgoing profitable activity. As The Perth Gazette and West Australian Times noted, by the time that a Daylesford woodcutter found the bodies of the Graham boys and Arthur Burman in September 1867, three months after their disappearance, the community had invested much in the children. The ‘pecuniary sacrifice’ associated with search efforts, the paper stated, ‘beside the offer for reward, cannot be less than £2,500’.Footnote 72 In economic terms, the ‘opportunity cost’ of closing business in order to search was not lost on this journalist or their readers; and Daylesford’s townsfolk were also undoubtedly aware of the ‘sacrifice’ that they had made for the children, much as other communities must also have been after shutting down business to engage in bush searches.Footnote 73 In the Terrell case, a segment of Blackwood’s population stopped working and searched Monday through Friday, and it was a fellow gold digger who found the lost girl. Of course, the social practice of ceasing business pursuits when children went missing was not limited to Victoria. For example, when a 22-month-old went missing near Weaner’s flat, on the Yorke Peninsula West of Adelaide in January 1872, hundreds of farmers ‘left their reaping-machines to join in the search’.Footnote 74 This suspension of ‘profane’ logics of economic activity, in favour of searching the bush, in such moments elevated the child to a sacred space, positioning the lost child both explicitly and implicitly as more important to the community than financial concerns.

Communal feeling

In instances in which a lost child was found alive, there are frequently references to searchers and parents sharing powerful emotional states. For example, when young David Williams returned safely home, after two days lost in the bush in 1872, the Hamilton Spectator wrote, ‘words could hardly describe the feelings of gratitude on the part of his parents … as well as to all those who so humanely took part in the search and persevered until the boy was found’.Footnote 75 Similarly, an eight-year-old boy named Tommy Hardy returned home after four days lost in the northern frontier of the wind-chilled island of Tasmania in 1873. There, the ‘strong muster’ of nearby inhabitants, who had searched by daylight and lantern, reportedly expressed feelings of ‘great joy’ when the ‘news arrived that the child had been found’.Footnote 76 The tendency to experience strong emotional states, and show them publicly, continued into the twentieth century. In late July 1910, an eight-year-old girl became lost in the bush bordering Queensland and New South Wales, where searchers combed the landscape for an entire week. When they found her on the seventh day,

the scene that ensued, after a long, trying search, was, it is said, a pathetic one. A coo-ee brought all the searchers together, when hardy men laughed hysterically together, giving vent to their feelings by all manner of means, while the black trackers hugged each other and laughed boisterously.Footnote 77

These sensations of strong, shared feeling, termed ‘collective effervescence’ by Emile Durkheim, not only bonded community members together in the happy cases. For example, the extreme feelings of mourning and loss in the Daylesford episode also united that community. There, newspapers reported that over one thousand people lined the town’s streets or followed reverently behind the children’s caskets in the funeral procession after their bodies were found.Footnote 78 The strength of communal feeling, after the initial tears, found articulation in literature, in a memorial and most recently in a walking track dedicated to the lost children.Footnote 79

Significantly, such expressions of shared emotion reverberate not only throughout the twentieth century but also well into the twenty-first. In June 2020, a fourteen-year-old autistic boy, Will Callaghan, became lost for two cold nights near Mount Disappointment, sixty kilometres north of Melbourne. Over five hundred Victorians searched for him, until he was found by an experienced bushman and returned to the searchers’ camp on 10th June. There, one search volunteer stated, ‘the mood at the camp’ was ‘absolute jubilation’. Considering, as The Guardian observed, that ‘police asked searchers not to break out in the usual cheers’ on Callaghan’s arrival in the camp (so as not to scare him), it appears that the collective effervescence of community members upon rescuing a lost child remains, to this day, etched into the rite of the bush search.Footnote 80

A settler colonial imaginary

In the nineteenth century bush searches, the colonists’ dependence on Aboriginal trackers and the latter’s superior knowledge of and connection with the land did not fit well within the settlers’ emerging social imaginary.Footnote 81 As scholars like Patrick Wolfe and Lorenzo Veracini observe, Australian settler society has been predicated on ‘replacing’ Indigenous peoples, by transferring ‘exogenous’ populations to expropriated land.Footnote 82 Settler Australians have often been reluctant to recognise Aboriginal peoples’ claims to land ownership, as it draws attention to the tenuousness of the settlers’ claims. While frontier violence and the internment of Victorian Aboriginal populations on reserves buttressed the settlers’ physical occupation of Kulin country during the goldrush, the settler colonial project of replacement also played out through the stories that defined frontier communities.Footnote 83 In some respects, the lost child trope belongs to this context of disavowal, dispossession and ideological distortion.

Settler discourses have frequently distorted Aboriginal people’s relationship with the land, often by erasing claims of ownership, ignoring Aboriginal people’s very existence or imagining Aboriginal people to be superfluous in Australian society.Footnote 84 Conversely, settlers deploy a variety of strategies to nominally ‘indigenise’ themselves, that is, settler Australians often tell stories that position themselves as being seamlessly and unproblematically at home on land which has been taken from Aboriginal groups.Footnote 85 Scholars like Kim Torney and Elspeth Tilley have established that settlers often interpreted the deaths of children lost in the bush as a kind of price that the community had to pay in order to belong on the land, like a sacrifice that somehow naturalised the presence of the settlers’ new communities.Footnote 86 In this vein, lost children could represent more than just an embodied experience of togetherness or the focus of a ritual that described shared values. At times, they seemed to establish a basis for a shared proto-national sense of settler identity. Considering that this belonging could be levied through the perceived sacrifice of Australian children’s lives, this iteration of the lost child narrative in some ways presupposed the mythology of the ANZACs, which would emerge along similar lines.Footnote 87

Yet the lost child narratives, which supported settler Australian identity, sat uncomfortably alongside the fact that the settlers usually relied on Aboriginal trackers to find lost children. Settler Australians performed mental gymnastics at times in order to avoid considering Aboriginal trackers’ essential roles in bush searches as being related to Aboriginal sovereignty. When the nine-year-old daughter of a man named Richard Collins went missing in the winter of 1886, although the settlers recognised the value of the trackers, this they attributed to superior eye ‘sight, instinct and senses of smell and hearing’.Footnote 88 It was often the case that settlers used animalistic metaphors, emphasising instinct or scent in this way, rather than intelligence or knowledge of land. Their refusal to recognise Aboriginal trackers’ cultured understanding of their homelands avoided the problems for settler identity which recognition of such mastery posed. Namely, if Aboriginal people had mastered the land then they may have owned the land by European proprietary standards, revealing that the very lands on which the settlers had built their new communities was contested.Footnote 89 Significantly, there is also a sad irony in the fact that settlers frequently entrusted Aboriginal adults with the task of rescuing lost white children, even as common sentiment among the settlers held that Aboriginal parenting was deficient and that Aboriginal children needed to be saved by settler adults.Footnote 90 When it came to bush-lost children, the discursive incoherence surrounding settlers’ conceptions of childhood and Aboriginality found articulation not only through action, but also through narrative erasure.

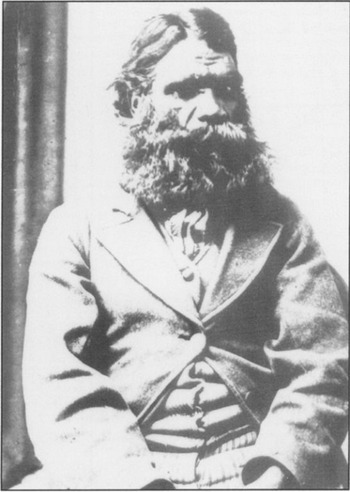

In the case of the Duff children, Aboriginal trackers, led by Junga-jinga-nook (also known as Dick-a-Dick), were the key protagonists who found the children (Figure 1). As Nonie Sharp points out, the original records reflect that the Aboriginal trackers, ‘through great sagacity and intelligence’ discerned the signs left in the landscape by the Duff children, and ultimately the trackers led the father to them.Footnote 91 The father wept and the trackers reportedly threw themselves about in joy and relief, having found the children alive after nine days. But over time, as the Duffs’ story was told and retold through art, literature and educative materials, the trackers’ role in the search was shifted to the margins; accounts in literature soon narrated that white settlers had found the Duffs.Footnote 92 It seems that in the nineteenth century, as the settlers reimagined their communities, Aboriginal people would still only have a place on the fringes of the new world they sought to create.

Figure 1. ‘King Richard’ or ‘Dick-Dick’, the tracker who found the Duff children, 20th August 1864.

Source: Photo courtesy of Horsham & District Historical Society.

Conclusion

Searches for lost children emerged on the common ground of care for children and alienation from an environment that settlers wished to comfortably call home. The goldrush of the 1850s saw populations burgeon in some Australian colonies, especially Victoria, with the emergence of numerous new communities with members from diverse origins of place, faith and ethnicity. The reasons for communities gathering together were generally economic. In Durkheim’s terms, ‘profane’ elements of culture such as work, exchange and entrepreneurial endeavour were insufficient predicates for lasting, successful, communal life. The social cohesion that these young towns required often came from beyond logics of economy. As the goldrush waned from the 1860s onwards, communal searches for children who became lost in the bush functioned as a secular rite that played a role in producing and reproducing moral communities that cut across denominational, ethnic and previous national forms of identity. Entire segments of communities would gather together, suspend economic pursuits and search for the children, often for days and weeks at a time. The explosive eudaimonia of finding the child alive, or the solemn reverie when the child perished, forged people together through strong communal feeling – and such emotions have continued to do so through to the present.

This article has redefined the Australian child-lost-in-the-bush archive to include the many children who were found alive but have been largely ignored by previous scholars. Taking these cases into consideration, as well as those in which children never returned, it emerges that searches for bush-lost children developed as sites of collective memory around which community cohesiveness could coalesce. Australian settlers positioned the figure of the child at the centre of an emerging rite from which common moral ground could be found and elaborated. The rite of the search would become disseminated through newspapers, literature, and word-of-mouth. Indeed, the discursive monolith of the ‘bush’, which referred to various types of ‘hostile’ landscapes of the Australian continent, enabled readers to participate in the searches remotely, as part of an imagining and feeling community in the colonies’ various climates.

In the gradually secularising settler colonies of Australia in the late nineteenth century, lost children at times functioned as a fulcrum on which communities could pivot, in the processes of establishing social cohesion and communal belonging. But, in spite of their centrality to so many of the searches for lost children, Aboriginal Australians would be relegated to the fringes of this part of the settler Australian imaginary; and this ideological rejection mirrored the fact that many new communities sequestered Aboriginal populations in the fringe camps and excluded them from the rights the settlers enjoyed. As such, the bush-lost child trope appears at first glance to be uniformly positive because of the high value it places on children and because it inspires communal cooperation. However, this trope has also been part of the process of naturalising the presence of settler communities – that is, replacement communities – established on land taken from Aboriginal people.

Acknowledgements

Sincerest thanks to Jennifer Jones who provided important feedback on an early version of this article in 2017, Kat Ellinghaus who gave insightful notes on the spoken version and Liz Conor, Catherine Gay and the anonymous reviewers who have also provided significant help in the development of this article. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge the input of Kim Torney, who helped us to polish the final version before submission for peer review and, finally, Tracey Banivanua Mar, who suggested that Tim conduct research on the lost child in late 2016.