1. INTRODUCTION

Traditional historical literature stressed a generalised 17th century crisis throughout the world. First proposed for Europe with its numerous dynastic, religious and state conflicts, it has now been expanded to include Asia and the Middle East as well. The fall of the Ming dynasty in China, numerous popular revolts, a climatic crisis known as the little ice age which may have affected agricultural production in many regions and world spanning plagues due to the increase in global shipping, are all said to have resulted in a supposedly linked general crisis from Asia to the AmericasFootnote 1 .

Nevertheless, recent scholarship has challenged the idea that there was a general crisis even in Europe, let alone throughout the world in this periodFootnote 2 . There were, of course, some unusual factors which did influence the world in this century. The religious wars in Europe, the collapse of the Ming dynasty, the increasing incidence of plague and an unusually cold period, were factors that affected some nations and not others. Declining empires created space for rising new empires and cities. Even the new trade with Asia and America was finally beginning to influence European consumption patterns, which led to the reorganising of traditional markets with winners and losers (Carmagnani Reference Brown2012; Crosby Reference Chiaramonte1972; and most recently Aram and Yun Casalilla Reference Álvarez Nogal2014).

There were of course some general trends which did affect most nations in the 17th century. European populations seem to have stagnated or declined after a major period of growth at the end of the previous century. Economists now suggest this was not caused by any Malthusian crisis of population outgrowing its food resources, but rather was due to the exogenous impact of ever more frequent plagues. At the same time the decline of overland intra-European trade was replaced by sea transport with a consequent shift of economic power to the North Atlantic ports (De Vries Reference Cook2009, p. 160). But there were numerous other factors which differed from region to region throughout the world. The religious wars of Europe were one endogenous event that was particularly intense in this century. The revolt of the Netherlands and subsequent Dutch and Spanish wars which lasted to 1621 followed by the revolt of Catalonia and Portugal in 1640 were the clear indications of the collapse of Habsburg European power. This decline was defined by the end of Spanish military hegemony in the Battle of Rocroi in 1643, and the defeat of one of the last great Iberian armadas by the Dutch in the battle of the Downs in 1639. In turn the Peace of the Pyrenees in 1659 ending Franco-Spanish conflict marked the rise of France under Louis XIV as a dominant European power. All these military and political events lead to the relative decline of Castile as a major world power (Elliot Reference De Vries2006, pp. 219-254). It resulted in the loss by Spain of an important part of its Northern European possessions.

Then there is the question of the actual economic decline of Spain itself, which by the middle decades of the century not only had lost its hegemonic role in Western Europe affairs but seemed to have stagnated economically. Data on Spanish exports to Europe show that traditional exports such as merino wool suffered either a stagnation or decline (Thompson and Yun Casalilla Reference Thompson and Yun Casalilla1994). There also seems to have been a relative slowing of population growth as well as regional migration with Madrid growing at the expense of smaller interior towns such as Toledo. Although population growth was still positive in the 17th century with the total numbers going from 6.8 million in 1591 to 7.5 million in 1700, there was wide variation among provinces and the share of the urban population (10 per cent) remained unchanged.

Spain began to decline from a relatively strong economic position within Europe and was estimated in 1570 to be second only to Italy in output per capita, and even as late as the middle of the 17th century, which seems to have been Spain’s deepest part of the recession, its output still surpassed that of England. But while the Spanish economy recovered in 1700, its pace was much slower than the rest of Europe and it was now significantly behind all the other major European powers (Álvarez Nogal and Prados de la Escosura 2013, p. 23). Even militarily, while Spain lost some significant European territories in this century, all attempts to wrest control of the Spanish empire in America by the new naval powers of the Netherlands, France and England ended in failure, except for the special case of Jamaica. Thus, the Northern Europeans were all forced to settle unoccupied American lands.

The so-called period of captivity of Portugal from 1580 to 1640 was good for Spain if not for the Portuguese empire. But this empire was losing its monopoly position. Portuguese and Christians were expelled from Japan by the 1620s and the Dutch replaced them in many markets. In fact by the 1610s Northern Europeans had more volume of shipping in the Asian trade than did the once dominant Portuguese (De Vries Reference Cook2009, p. 184). Even after Portugal was able to recover Recife and part of its African holdings after 1640, Portugal itself experienced a stagnation of population, several serious harvest failures, significant devaluation of its currency, and probable economic decline until 1670s (Freire Costa et al. Reference Elliot2016, pp. 109-167).

2. SPANISH AMERICA DURING THE 17TH CENTURY

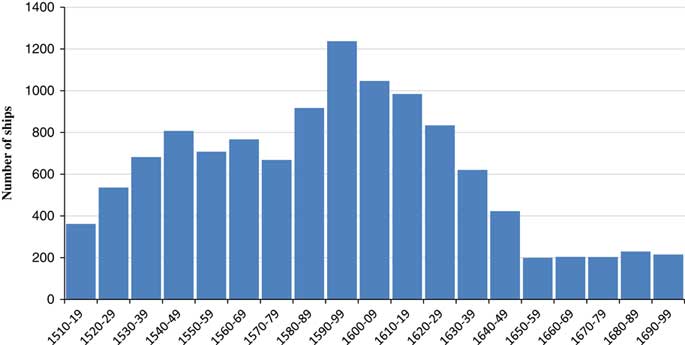

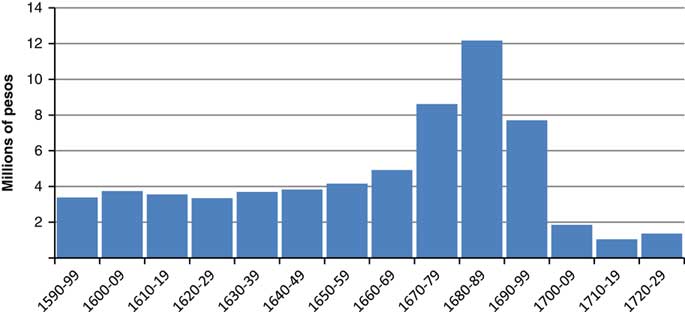

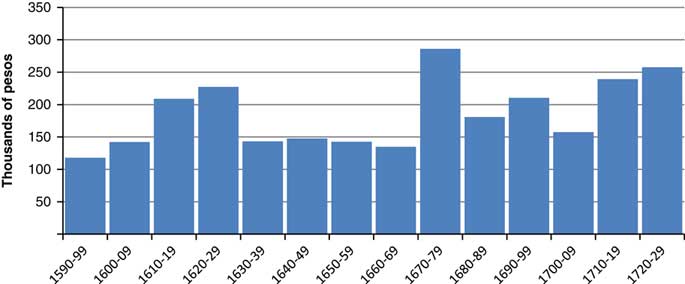

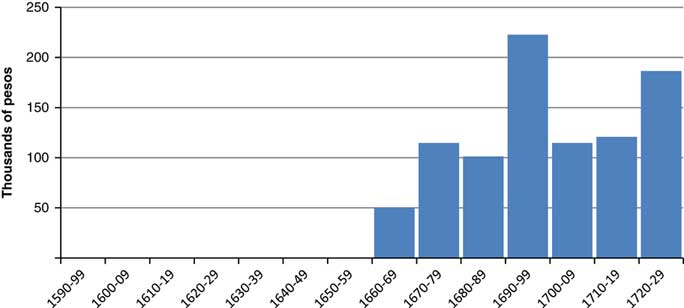

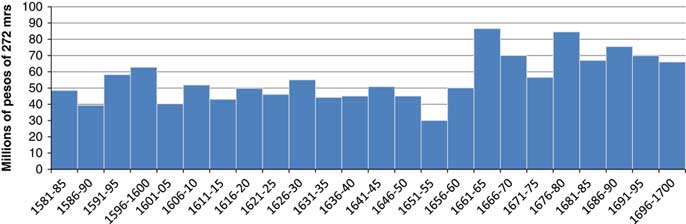

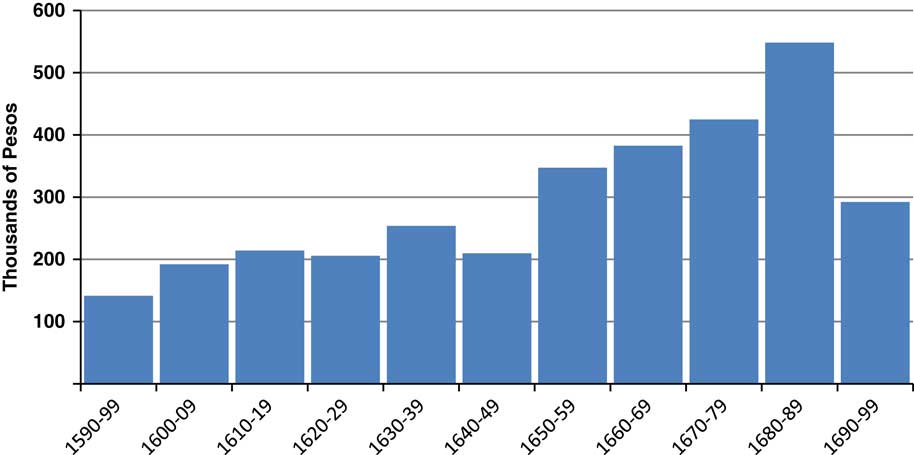

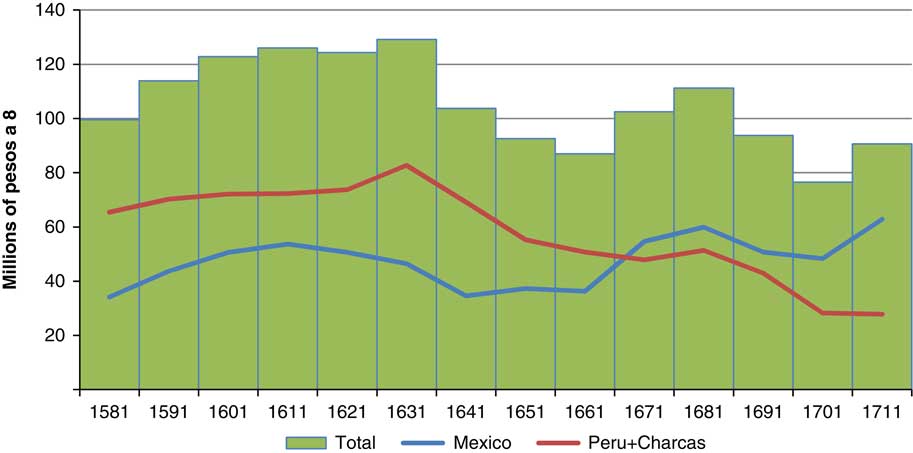

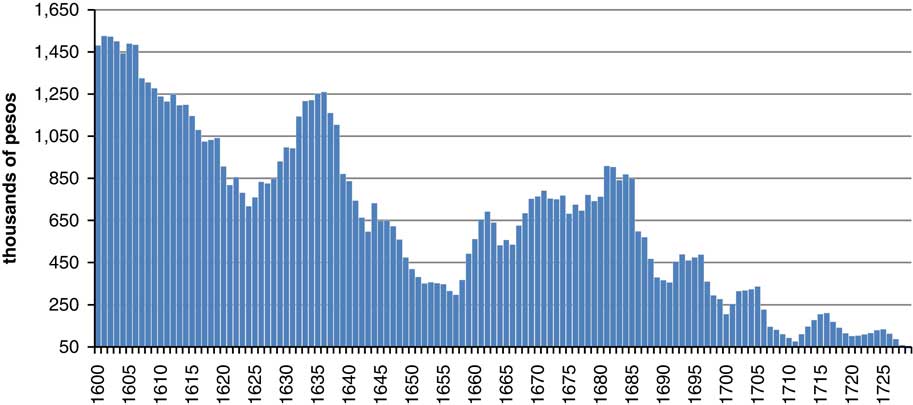

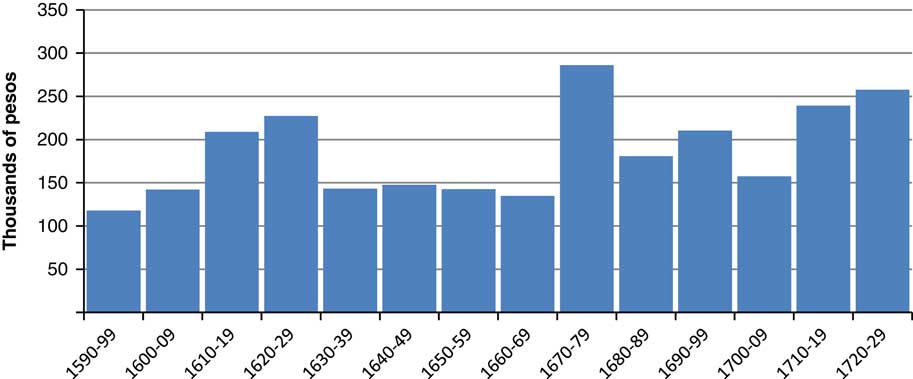

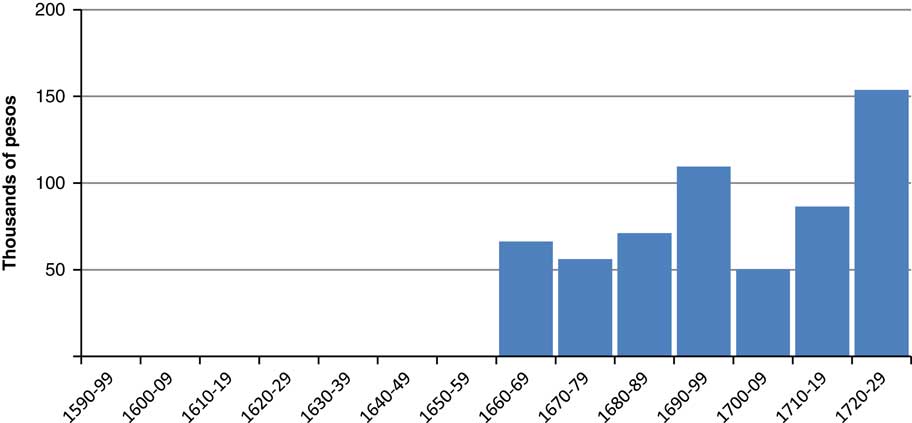

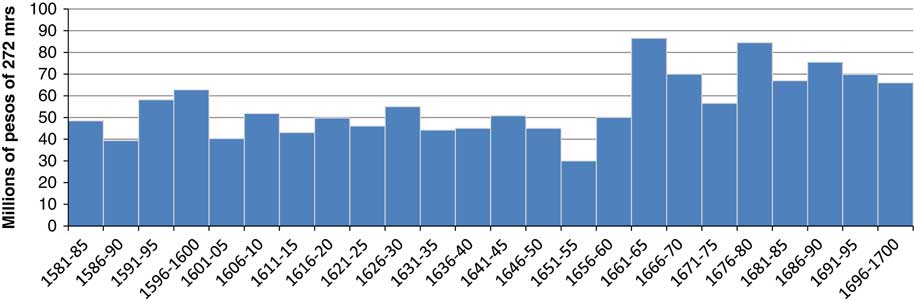

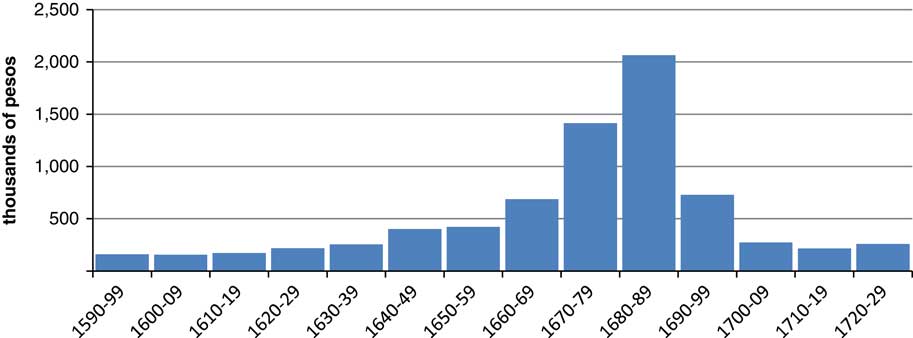

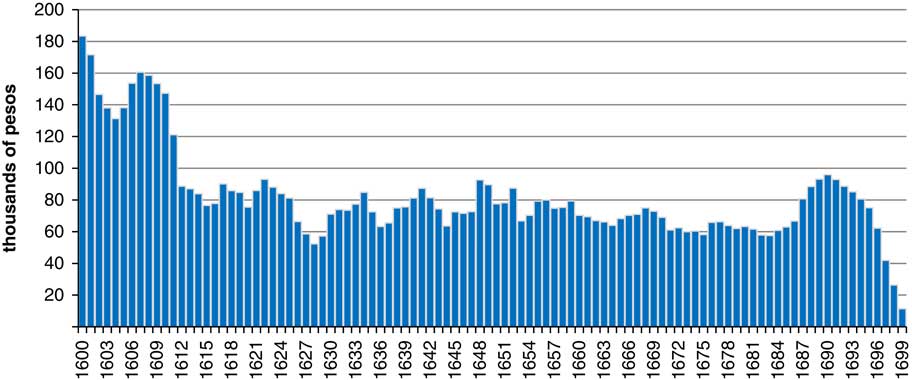

If Spain was losing its relative political power in Europe and some of its key territories on the continent, and then lost Portugal with its Asian, American and African empires, did this mean that Spanish America also suffered a crisis? If Spain and Portugal stagnated or declined, did their American colonies also decline, or did they in fact continue to grow and thrive? Until recently it was assumed that there was a significant crisis in the Americas. The theme of a 17th century crisis in America is based on a series of classic studies. Those of Earl J. Hamilton who used Spanish archival material to show a severe decline in New World silver imports into Spain in the 17th century (see Graph 1). In turn Woodrow Borah’s demographic studies argued that a new post-conquest collapse of the Amerindian populations occurred from the 1590s until 1700 (Borah Reference Bertrand1951), and Pierre Chaunu (Chaunu Reference Bustos Rodríguez1956) and Lutgardo Garcia Fuentes’s detailed study of Spanish American trade (García Fuentes Reference Freire Costa, Lains and Münch Miranda1980) showed a major decline in commerce between America and Spain in this century (see Graph 2).

Graph 1 American bullion arrivals in Spain, 1581-1660 (by quinquennium) Source: Hamilton (Reference Giraldez2000, table 1, pp. 47).

Graph 2 Volume of Spanish ships going to America from Sevilla and Cadiz, 1600-1729 Source: Chaunu (Reference Bustos Rodríguez1956, vol. VI, pt. 1, pp. 328-330) and García Fuentes (Reference Freire Costa, Lains and Münch Miranda1980, pp. 216).

This model of a basic 17th century crisis in the Americas has been challenged by a growing number of studies beginning in the 1980s. Klein and Tepaske (Reference Hamilton1981) demonstrated that actual bullion production in the 17th century New Spain was stable or grew for most of this century. In turn the important work of Morineau showed that American silver imports into Amsterdam were significant and grew in most of the 17th century reaching their all-time peak in the 1690sFootnote 3 . There has even been a modest restatement of the royal funds arriving in the 1630s and 1640s through a revision of the sources used by Hamilton, suggesting that even Crown-owned silver was greater than he assumed. This has to do with the funds arriving in the silver fleets which were listed as belonging to private individuals but which in this period and later in the century were in fact royal income. These private funds had evaporated after mid-century government taxation and arbitrary confiscations of private funds from the arriving fleet resulted in private shipments of silver no longer being carried in the annual silver fleets (Álvarez Nogal 1998).

But if American mine production was stable and possibly increasing, and official shipping was seriously declining throughout the century, how did all the vast quantity of private and even public silver arrive in Spain and even more importantly how did it get to the Netherlands? How silver left Spain is well documented by the Steins who show how illegal and unrecorded American silver shipments left Spain in innumerable ways from legal arrangements to total fraud. There were silver payments to foreign bond holders of Spanish debt, then there were the payments to the 88,000 troops stationed in the Netherlands which were paid and supplied by foreign merchants, and finally there was even outright theft by the legal French, English and Dutch merchant communities resident in Seville and Cadiz. Even Spanish merchants participated in this illegal trade (Stein and Stein Reference Sánchez Albornoz2000, Ch. 3).

All this illegal trade and commerce was made possible by the corruption of the Spanish Administration at home and overseas. The sale of government offices by the financially challenged monarchy was intense in the 17th century and occurred at all levels of administration both at home and in the empire. This vastly increased the influence of the merchant class in government administration and prevented any effective control over contrabandFootnote 4 . A classic case for this takeover of local government by the merchant class is that of the merchants of Mexico City in the mid-17th century. These leading merchants succeeded in controlling the local viceregal Mint, and most of the key government offices in the new mining districts of the north either by buying these offices directly, or served as financial guarantors or creditors of those buying them. They also controlled the transport of silver and provided the credit for mercury purchases. They even illegally entered into joint business ventures with local government officials. The result was that they had privileged information about local mining conditions and were also able to successfully evade taxation and produce even unregistered minted silver coins. The private merchants totally controlled silver production and minting by the second half of the century (Del Valle Pavón Reference Cook2011). The ports were another area for significant government corruption with many high-level officials accused of significant illegal commercial activityFootnote 5 .

These intertwining of government and private interests made possible a very active direct trade of colonials with foreign ships coming from and returning to foreign ports. The relative isolation of the American colonies and the decline of Spanish shipping further encouraged active trading with foreign nationals in foreign vessels. Thus a significant part of the wealth of America and of its international trade went unregistered in the accounts of the metropolitan government. This trade was initially in precious metals, precious stones and expensive dyes — high priced and low weight exports. But quickly American exports to Europe included tobacco, hides, cacao, and sugar, goods of heavy weight and lower value. These were also products in demand in the Northern European markets (Fernández de Pinedo Reference Domínguez Ortiz1984, p. 125).

Not only were the colonials producing ever more agricultural products along with their precious metals, they were increasingly creating local industry. Although we are still unable to fully determine the agricultural economy in this periodFootnote 6 , several scholars have shown that the 17th century was a period of rapid growth of colonial industries. Lynch has argued that by this period Spain was no longer sending basic goods to the Americas as it had in the previous century and that the colonies were able to satisfy most of their primary needs through the systematic growth of local agriculture and manufactures everywhere in the Americas (Lynch Reference Klein and Tepaske1981, vol. II, Ch. 6 and 7). This is supported by Margarita Suarez for the Andean region who also argues that the 17th century saw major growth of an internal market, of local American manufactures and a major illegal international contraband trade (Suárez Reference Sánchez Santiró1999). Spanish American yards were even building 40 per cent of the ships used in the transatlantic trade by the 1640s, and together with foreign built vessels, these American and foreign vessels dominated the commercial fleets shipping goods from Spain to the Americas (Lynch Reference Klein and Tepaske1981, vol. II, p. 215).

But even Spanish trade with the Indies was growing in the 17th century. Several studies suggest that both the official volume of shipping reproduced by Chaunu was not representative of actual volume of shipping and that Spanish exports to America of fine textiles, metal products and paper increased dramatically in the second half of the 17th century even as shipping seemed to go into severe decline and official figures of silver imports declined dramatically to less than 2 per cent of their 1650 level (García Fuentes Reference Flynn and Giráldez1979; Oliva Melgar Reference Martínez2004, Reference Morales Padron2005). Obviously colonials were buying these goods with illegal silver and a range of exports, going from the traditional high cost items of the 16th century to more common and cheaper bulk products now being produced in quantity in the Americas such as tobacco, hides, cacao and sugar (Fernández de Pinedo Reference Domínguez Ortiz1984, p. 125). If American imports of European goods remained constant or increased in this century, even for Spanish made products, then the key factor was the development of a significant contraband trade of alternative ships and foreign merchants, a trade which included even minted silver coins as well as unminted silver and goldFootnote 7 . All this was occurring as there was a dramatic decline in royal silver arrivals from America especially in the post 1650 period. Yet this was a period when private unregistered silver imports appeared to be boomingFootnote 8 .

The situation of the economy in Spanish America does not seem to show a steep decline during the 17th century. The evidence presented so far seems to indicate — on the contrary — some signs of resilience regarding the situation in Europe. To assess in a much-nuanced manner the economic output of Spanish America during the 17th century, it is important to revisit the data available. Thanks to the efforts of several scholars during the last 30 years, it is possible now to have a clear understanding of the main areas of the colonial economy. Precisely, the pages that follow present a coherent account of the situation for the trade and commerce, state finance, mining and population.

3. TRADE AND COMMERCE IN SPANISH AMERICA REVISITED

As several recent authors have pointed out, the legal Andalusian monopoly on colonial trade given to Seville and Cadiz was anything but a monopoly. Spain alone could not satisfy the manufactured goods demanded by the colonial market which explains the vital role of foreign merchants in even the legal trade. Thus Colonial American trade despite all the official restrictions was in fact a relatively open international trade between numerous European nations and Spanish AmericaFootnote 9 . Contemporary reports from local European consuls suggest that 80-90 per cent of the goods shipped legally in the ships of the Carrera de Indias were of foreign origin (Bustos Rodríguez Reference Bonialian2005, p. 360). Moreover a recent study of the official registers from the second half of the 17th century suggest that the official value of reported exports for the annual flotas were 10 per cent or less of the actual value of those cargoes estimated by foreign consuls (Oliva Melgar Reference Martínez2004, p. 48, table 3). There were also other major loopholes in the legal monopoly. The Canary Islands, for example, were considered a key entry point for smuggled Northern European goods entering the convoy system maintained by Spain in the 16th and 17th centuries (Pérez-Mallaína Bueno Reference Pacheco Díaz1980). Thus, even the official legal trade was in fact a non-restrictive international trade and it is evident that the majority of American silver ended in other European countries for the goods they sold to the AmericansFootnote 10 .

Within Andalucía a well-established group of European merchants were key suppliers to the colonial trade. French textile exports to Cadiz and Seville in this period were massive and primarily directed to the American market — with payments being made primarily in American silver (Girard Reference García Fuentes1932b, Chs. 8 and 10). Flemish and French merchants were well established in Seville, as well as in Cadiz by the last decades of the century when this bigger port became the dominant port for American tradeFootnote 11 . The English merchants quickly followed them in the mid-17th century establishing legally recognised merchant communities in Andalucía, and all three groups obtained, directly or indirectly, the right to trade with America. All these foreign merchant communities also provided the credit for Spanish merchants to purchase European goods used in the American trade. In a detailed breakdown of the value of products shipped to the New World in the fleet of 1686, only 6 per cent of the value of all goods shipped was of Spanish origin (Morineau Reference Marchena1985, p. 267, table 44).

A financial and politically pressed Crown also assisted in this European takeover of legal American trade. Between 1645 and 1667 the Spanish Crown issued decrees or signed international treaties setting up these privileged trading communities for the three major groups of foreigners (Stein and Stein Reference Sánchez Albornoz2000, pp. 58-64). Finally there was a never-ending battle by the Europeans to gain control over the Spanish asiento, or the exclusive right to import slaves into the Spanish American colonies. This highly desired contract was well known to allow the contracting nation to engage directly in American commerce and was a major conduit of purchases of silver and other American produced goods. In 1601 Spain opened up its slave trade to foreign merchants and by mid-century even English slavers supplied some slaves to Spanish America, with Jamaica and Barbados permitting direct sales to Spanish America in 1663. So lucrative was this trade that the English insisted that it be part of peace negotiations in 1711 and finally got their asiento in 1714 (Sorsby Reference Ruiz Guadalajara1976, pp. 7-8).

Then there was actual contraband trade in foreign ships that paid no duties. These came from the new American centres established by Northern Europeans in the Caribbean which became thriving centres for contraband trade to Spanish America. Many point to the establishment of the Dutch colony of Curação in 1634 as a key development of this new international commerce, though in fact it was not until the second half of the 17th century that the island became a major trading centreFootnote 12 . But already in 1627 the English were in Barbados, and they were quickly followed by the French settlement of Martinique in 1635, with the English taking Jamaica from Spain in 1655 and — 4 years later — the French settlement of the western end of La Española, precisely in the lands abandoned by the Spaniards. This north coast of Española in turn had been forcefully abandoned by royal officials in 1605 because of its active role in the contraband trade. The Anglo-Spanish Treaty of 1670 recognised all British conquests and settlements in West Indies, which included not only Jamaica and Barbados, but also several islands in the Lesser Antilles (St. Kits, Nevis, Antigua, etc.). Once firmly established, Jamaica, along with Curação became major centres for contraband trade with Spanish AmericaFootnote 13 . Europeans traded from the Pacific to the Southern Atlantic colonies. Everywhere the colonials were big consumers of higher prices textiles, metal products and other manufactured goods produced by the non-iberian European countriesFootnote 14 .

Portuguese, Dutch, English and French trade with colonial Latin America became quite significant in this century and their imported goods occupied a significant space in the colonial economy. The Portuguese presence in America was actually legal until 1640. During the period that the two kingdoms were united, Portuguese merchants became an important presence in all the major Spanish American ports, from Lima to Veracruz and Puerto Rico. The expulsion of these merchants and their prosecution by the Inquisition in the 1640s temporarily disrupted colonial trade organisations throughout the AmericasFootnote 15 . But local merchants were able to re-establish trade linkages with the Dutch, English and French. In the mid-17th century it was estimated that in New Spain two-thirds of goods imported were from contraband and only a third was legally imported. It was also estimated that even a quarter of the silver embarked in Spanish ships at that time was unregistered (Malamud Reference Klooster1981, p. 33). Humboldt as late as 1800 maintained that illegal imports from Northern Europe were valued at 4.5 million dollars and that at least 2.5 million dollars of ingots of silver and gold were annually exported from Mexico (Cited in Bernecker Reference Álvarez Nogal and Prados de la Escosura2005, p. 134). Moreover in the second half of the 17th century both the Netherlands and England were allied with Spain against the rising power of France. Thus English and Dutch traders were welcome in Spanish and Canary ports.

Finally, the 17th century was also a period of extraordinary growth of inter-continental trade. So important had the Pacific trade between Peru and New Spain become that in 1631 the Crown prohibited it altogether on the grounds that it was negatively influencing the Portobelo Atlantic markets and was also draining silver to AsiaFootnote 16 . But the prohibition was ignored as Peruvian ships brought Peruvian minted and silver bars, mercury from the Huancavelica mines, cacao from Guayaquil, wines, olives and olive oil to the ports of New Spain in exchange for Asian, European and Castillian goods. By the last decades of the century there was a boom in this illegal trade, reflecting the growing consumption of the Peruvian marketsFootnote 17 .

4. ROYAL EXPENSES IN COLONIAL LATIN AMERICA

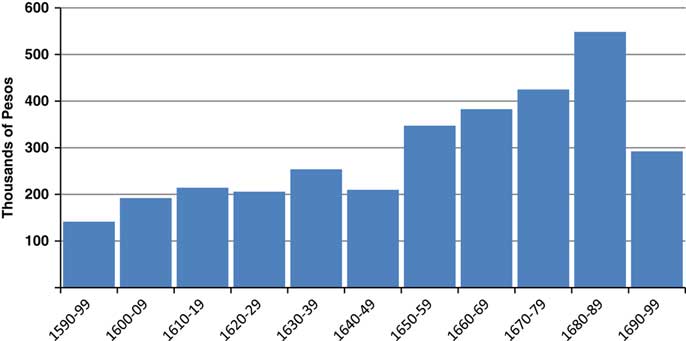

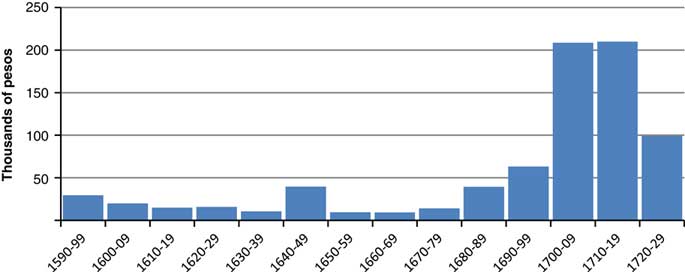

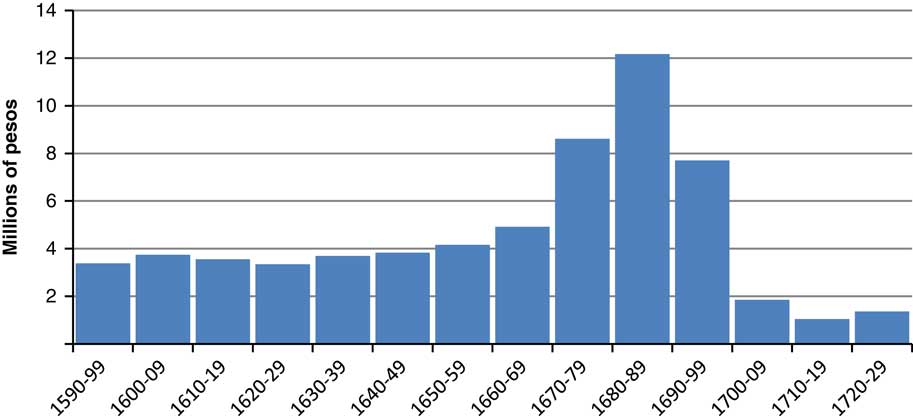

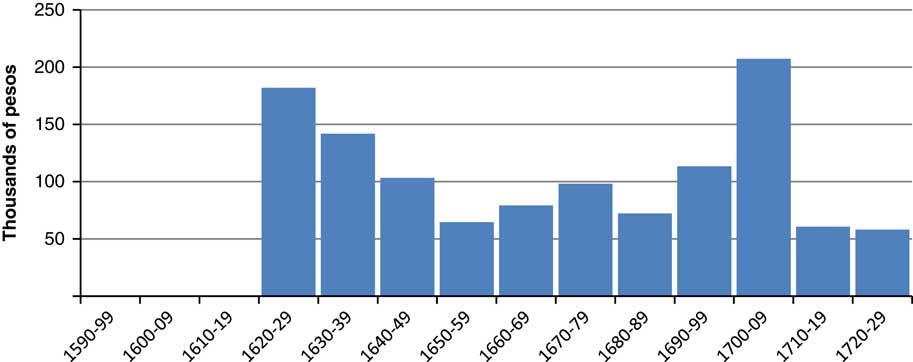

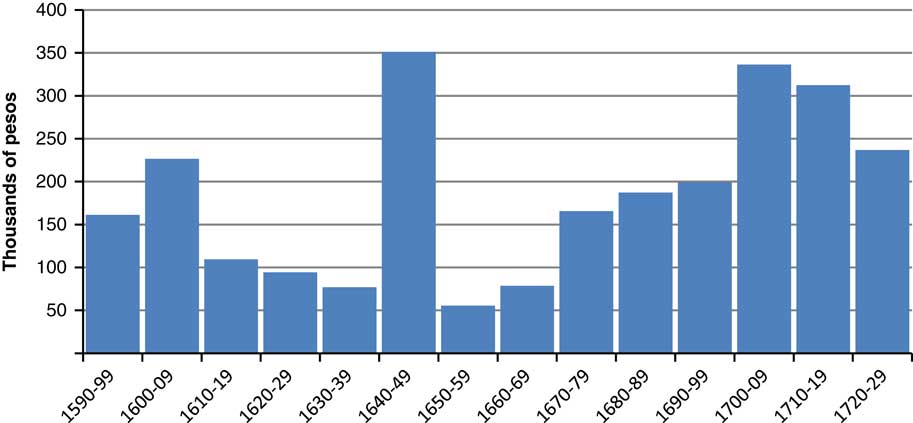

This developing colonial economy is also reflected in government expenditures. All studies indicate a serious decline of bullion coming to Europe from American mines in the second half of the 17th century. The American cajas reflect this decline in funds shipped overseas (see Graph 3). Even though mine output was stable, and royal income in most treasury offices were stable or increasing, this decline in overseas export of specie strongly supports the thesis that more royal funds were being expended locally and this can be seen in the transfers from the rich fiscal offices to the debtor ones, most of whom were on the frontiers of the empire. From the North American frontiers to Chile and the Rio de la Plata in the far Southern cone, Mexican and Peruvian government funds were being used to maintain troops, build fortifications and pay royal salaries (see Map 1). In this period impressive fortifications were built throughout the Indies while local garrisons and royal officials were subsidised and even some frontier settlements were financed by royal funds.

Graph 3 American revenues sent to Spain and Philippines, 1591-1749 Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Hamilton1981, table 3, pp. 133).

Map 1 Yearly administrative cost of the indies and presidios financed by the real hacienda (C.A. 1650) Source: Biblioteca Nacional de España (BNE), Raros, 3080 and Biblioteca Nacional de España (BNE), Manuscritos, 3024.

These transfers of royal funds (situados) from the central treasuries began in the 16th century and continued uninterrupted to the end of the colonial period, with sums increasing steadily throughout the period. Especially after the 16th and early 17th centuries attacks by French, English and Dutch privateers and professional armies on both the Pacific and Atlantic colonies of Spanish America this funding steadily increased as the ports from Florida to Chile were fortified, especially in the late 16th and throughout the 17th centuries. It was this funding which was crucial in the successful defense of the Spanish American empire until the early 19th centuryFootnote 18 . As many commentators have noted it is evident that the Crown itself by the end of the 17th century was spending far more of its tax income in America than it was shipping home. At the beginning of the century the Viceroyalties of Peru sent over half of its total income to Spain and by the 1630s New Spain was sending 48 per cent of its total revenues to Spain and the Philippines, but by the end of the century both were shipping 10 per cent or less of their gross income to these two destinations. Peru which had dominated remittances in the first half of the century, sending over half its total revenues to Spain, virtually stopped sending funds to Spain by the end of the century. Between 1590 and 1729 some 23 per cent of New Spain bullion exports went to the Philippines, essentially as a «situado», and these islands absorbed 11 per cent of all bullion shipped in this period — another major and steady drain on American revenues which did not go to Spain (see Graph 3 and Map 1).

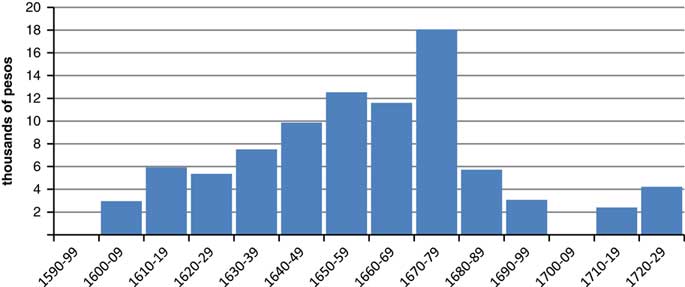

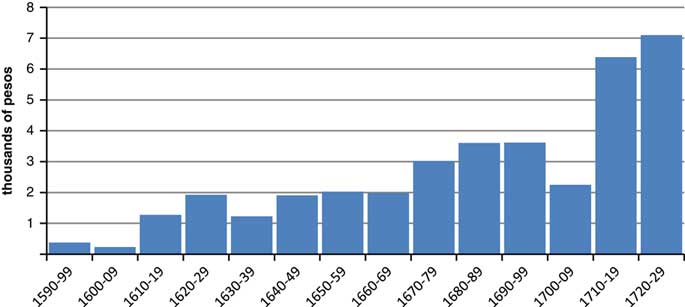

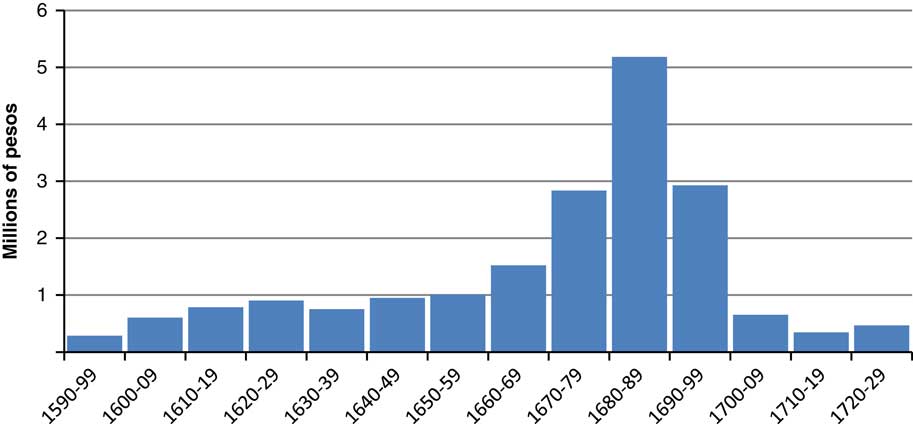

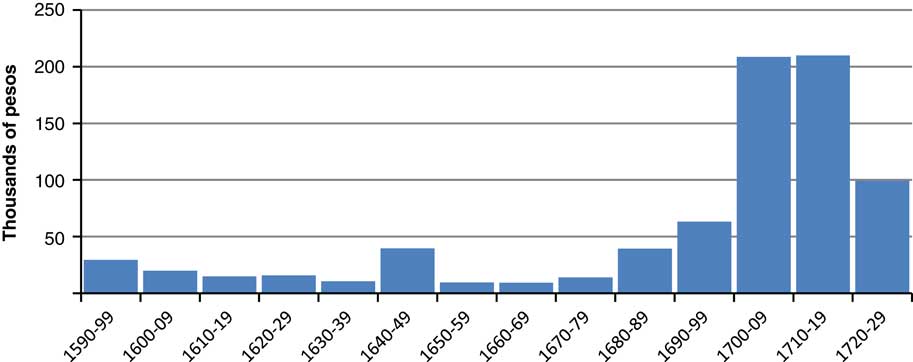

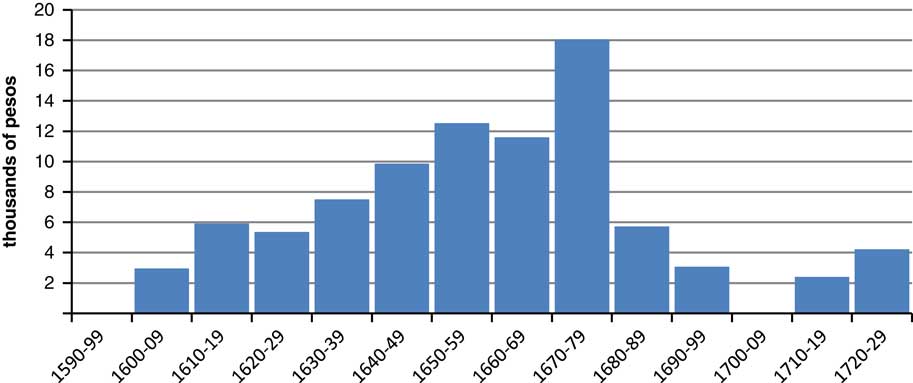

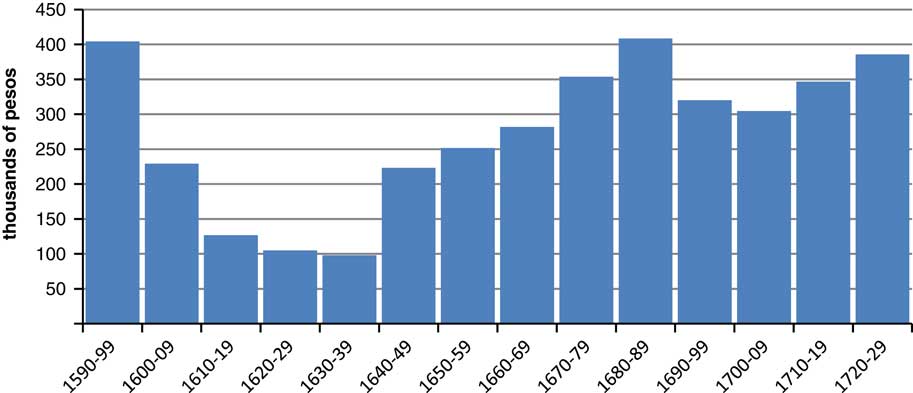

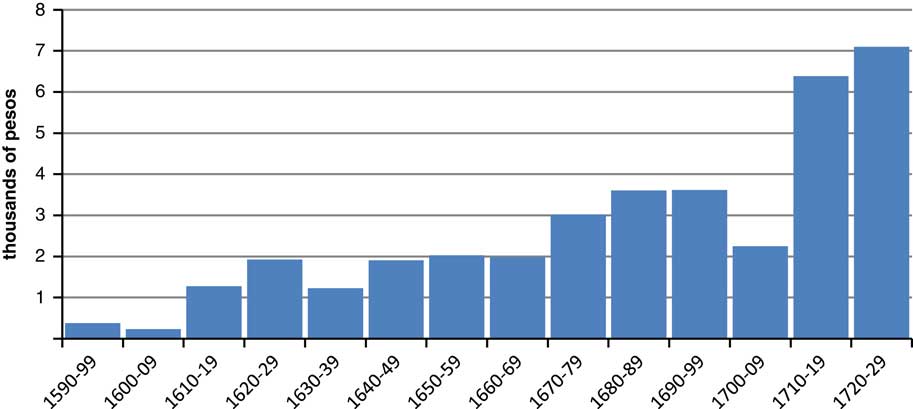

In the Caja of Lima, for example, the sums which supported the far-flung forts and garrisons covering all the major coastal ports of Peru as well as those of the Rio de la Plata and Chile grew steadily through the century until the 1680s. Lima from the late 1590s supplied a steady subsidy to Santiago de Chile, first as a «socorro» and then in 1605 as a formal «situado». Then in 1658 was added the situado for Valdivia, and finally a very significant third situado was added in 1675 for Panama. By the 1670s these war and subsidy expenditures accounted for some 39 per cent of total Lima expenditures, and by the 1680s reached 47 per cent of all expenditures. While the decline of military expenses in the 1690s led to a relative decline of these costs, they still made up about 42 per cent of actual costs of the Lima Caja (see Graph 4-6)Footnote 19 .

Graph 4 Average total expenditures of Caja of Lima by decade, 1590-1729 Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, Reference Klein1986).

Graph 5 Average war expenses of Caja of Lima by decade, 1590-1729 Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, Reference Klein1986).

Graph 6 Average situado expenditures for Chile, Valdivia and Panama, Caja de Lima by decade, 1600-1699 Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, Reference Klein1986).

What is impressive is that war expenditures were initially much higher in Peru than in Mexico. Peru dominated these expenditures until the 1690s. Only in the first decade of the 18th century did New Spain’s military expenses finally equal and eventually surpass those of Peru. Thus, the combined Lima and Mexico treasuries expended 43 per cent of their total budgetary expenditures on war related activity from 1600 to 1699, in turn these war expenditures represented 44 per cent of the total income generated by these two principal cajas (see Graph 7).

Graph 7 Average war expenditures of the Viceroyalties of Peru and New Spain by decade, 1590-1729 Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, Reference Klein1986).

The Caribbean can be considered another classic deficit frontier, and for most of the 17th century, the central treasury office of Mexico consistently provided substantial sums for Florida, Habana and Puerto Rico and more sporadically to Santo Domingo and Santiago de Cuba in the form of situados (see Table 1)Footnote 20 . Their local economies in this century were incapable of covering the costs of maintaining local forts and soldiers and even civil government administrators.

Table 1 SITUADOS SENT FROM CAJA DE MÉXICO TO THE CARIBBEAN PRESIDIOS, 1600-1699 (TOTAL FIGURES IN PESOS DE A OCHO BY DECADES)

Source: Reichert (Reference Parker and Smith2012, pp. 58, 65).

5. ANALYSING THE ECONOMIC OUTPUT OF SPANISH AMERICA IN THE 17TH CENTURY: MINING PRODUCTION, COMMERCIAL CIRCULATION AND POPULATION

Using the reconstructed database of Spanish colonial fiscal records generated by Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, Reference Klein1986), we can see in more detail how various sectors of the colonial Spanish American economy and population developed in the 17th centuryFootnote 21 . Here we examine mining, international trade and population based on both actual mine production as well as mining and minting tax income, all the trade taxes and Indian tribute income over the course of the century in the three leading regions of Spanish America — the provinces that went to make up the Audiencia of Charcas (Bolivia), and the Viceroyalties of Peru and New Spain (Mexico) which accounted for at least 80 per cent of the royal revenues in the Americas.

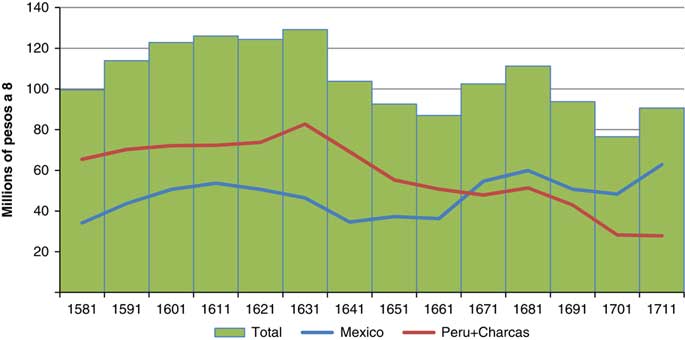

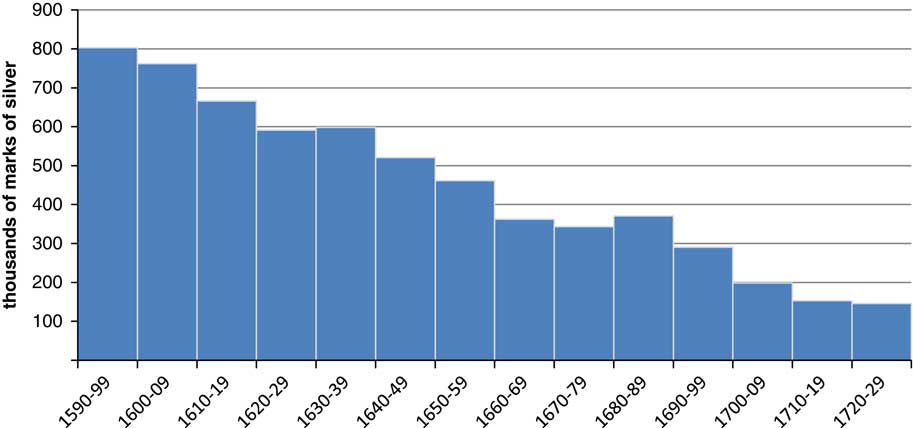

What we see from the mining data of both estimated production and mining and minting taxes is that while there were short swings in total output, overall there was a steady production throughout most of the century with a relative decline in the mid-century followed by a rising trend of production in the last decades of the century. The estimate of TePaske of actual gold and silver production shows steady rising production in the first third of the century followed by a short decline and another increase in the 1670s and 1680s, followed by another decline in the last decade (see Graph 8). This overall pattern hid some significant changes, the most important of which was the relative decline of the formerly dominant mines of the Audiencia of Charcas and the dramatic rise of the new mining centres in the north of New Spain (see Graph 9). Potosí, the chief silver centre of both the Audiencia of Charcas and the Viceroyalty of Peru suffered a major crisis in the early 17th century after reaching a peak in the 1590s and then began a steady secular decline (see Graph 9). For the Charcas region the mines of Oruro reduced the rapidity of the decline, though the trend was negative for the century (see Graph 10)Footnote 22 .

Graph 8 Bullion production (gold+silver) in Mexico, Peru and Charcas, 1581-1711 Source: Tepaske and Brown (Reference Sanz Tapia2010, pp. 20-21).

Graph 9 Average annual silver production in Potosí, 1550-1809, per decade Source: Bakewell (Reference Thompson and Yun Casalilla1975, pp. 92-97).

Graph 10 Annual mining tax income of Audiencia of Charcas, 1600-1729 (5-year moving average) Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, Reference Klein1986).

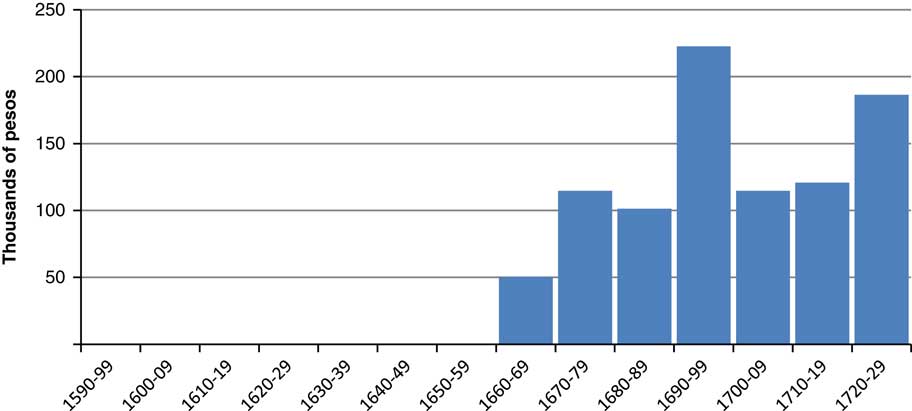

But just as there was a crisis in mine output in Charcas and its primer mining zone of Potosí, there was a major growth of silver mining in the Viceroyalty of New Spain. There was a boom in the mining zone of Zacatecas — more precisely in Sombrerete, and while the new Mexican mining zone of San Luis Potosí faltered, the other late 17th century producers, Guanajuato and Pachuca were expanding production rapidly thus increasing the viceroyalties overall mining income decade after decade from the mid-17th century onwards (see Graphs 11–14).

Graph 11 Average mine income in Zacatecas by decade, 1590-1729 Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, 1986).

Graph 12 Average mine income in S. L. Potosi by decade, 1620-1729 Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, 1986).

Graph 13 Average mine income in Guanajuato by decade, 1660-1729 Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, Reference Klein1986).

Graph 14 Average mine income in Pachuca by decade, 1660-1729 Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, Reference Klein1986).

All of these mine production and tax income figures re-enforce the findings of Morineau which saw a steady arrival of New World silver to the markets of Northern Europe, even despite their decline within Spain itself, at least in terms of royal receipts if not private silver arrivals. According to the data of Morineau, bullion arrival in 17th century Amsterdam suffered no secular crisis in the 17th century and reached new high levels in post 1661 period (see Graph 15).

Graph 15 Bullion arrivals to Europe from all Spanish America, 1581-1696 Source: Morineau (Reference Marchena1985, p. 250).

Were these mining trends unique in this period or can we see similar trends in internal and external colonial trade in Spanish America? Here some surprising patterns emerge which challenge the idea of a generalised crisis. Using the trade tax estimates for the key ports of Veracruz and Acapulco in Mexico we see a similar pattern on both oceans. They both experienced a mid-century boom lasting no more than a decade or two, followed by a short-term depression and then both experienced a dramatic increase in the post 1660 period (see Graphs 16 and 17).

Graph 16 Average trade tax income for Caja of Veracruz by decade, 1590-1729 Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, Reference Klein1986).

Graph 17 Average trade tax income for Caja of Acapulco by decade, 1590-1729 Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, Reference Klein1986).

The district of the audiencia of Lima had minimal mining production, with its mine taxes from all known treasury offices being an average less than 30,000 pesos per annum. Lima’s treasury income was most heavily based on trade and commercial taxes and tribute income. Thus despite the decline of mining in the region, there was in the 17th century an increase in colonial and Pacific trade as well as significant growth in agriculture and manufacturingFootnote 23 . This was shown most clearly in the principal Caja of Lima. Here there was steady growth into the penultimate decade of the century and only then did decline occur (see Graph 18). Clearly despite declining regional mine production, there was no 17th century crisis as seen in the trade data for this crucial South American portFootnote 24 .

Graph 18 Average trade tax income for Lima by decade, 1590-1729 Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, Reference Klein1986).

What of population trends, another important theme discussed in the General Crisis literature. All studies suggest that there was a steady flow of Spaniards and African slaves into the colonial American empire in this century, which meant that these two groups and the mestizo or casta population was growing throughout the 17th century. But what of the majority Amerindian population and its trajectory during this period; is the argument of the Borah crisis essay sustainable from the information available on tribute income lists? While there is little doubt that the Amerindian populations in all regions continued to decline in the first third of the 17th centuryFootnote 25 , they seem to have stabilised or grew again thereafter although often at a lower level than in the 16th century. In Potosí, for example, the only Charcas regional treasury office for which we have data for this period, by the 1610s the Indian tribute population had stabilised and continued until the very end of the century (see Graph 19).

Graph 19 Annual tribute income in Caja of Potosí, 1600-1699 (5-year moving average) Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, Reference Klein1986).

Data from various New Spain treasuries indicates some regional variation with most tribute income stabilising by the 1630s and growing later in the century. Perhaps the best treasury office for capturing central Mexican Indian population is that of Mexico City which incorporates the tribute from the Valley of Mexico as well as the tribute collected from the dense Indian population centres of Oaxaca and Puebla (those treasury offices were not established until the 18th century)Footnote 26 . Thus the tribute income in the Caja de Mexico reflects the population growth of all central New Spain and the trend is very clear: Indian population grew fast during the second half of the century. At the same time Merida seems to have been a region whose Indian population had declined least in the early colonial period and whose population was growing steadily throughout the century until the 1680s (see Graphs 20 and 21).

Graph 20 Average tribute income for Caja of Merida by decade, 1600-1729 Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, Reference Klein1986).

Graph 21 Average tribute income for Central Mexico Caja by Decade, 1590-1729 Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, Reference Klein1986).

Finally, there is the tribute lists from the mining zone of Zacatecas which is not as direct a relationship with Indian population growth since it was a major zone of immigration. While this zone did not have initially a large resident Indian population, the new mining camps and towns that appeared after the chichimeca war in the north of the viceroyalty (1556-1590) were settled mostly by Indian populations that migrated from the central and southern regions of the viceroyaltyFootnote 27 . Those that choose to abandon their Indian communities were seeking better wages and in general, were trying to evade control and tributes from the zones that had a well-established government. Some of the loss of population from the central zones of Mexico can be partly explained by this mining rush that happened precisely at the turn of the 16th century and continued to attract population from central Mexico during the first half of the 17th century (see Graph 22). The Crown attempt to establish better controls over the population that migrated there led it to impose tribute on what were now mostly mestizo towns, a tactic which was protested by the local populationsFootnote 28 .

Graph 22 Average tribute income for Caja of Zacatecas by decade, 1590-1729 Source: Klein and Tepaske (Reference Jiménez Estrella1982, Reference Klein1986).

If these tribute lists adequately reflect the population on which they were based — adult Indian males — these findings support the critiques of the numbers of Borah and his model of demographic decline and economic crisis (Chiaramonte Reference Caño Ortigosa1981). All the cajas seem to be following the same secular trend which suggests that Indian population in most regions of the empire finally ended their dramatic 16th century decline and had finally begun growing again early in the 17th century. If these tax figures are indicating basic population changes, then it can be argued that Borah’s position that Indian population was in constant decline until 1700 can be rejected. This was not to say there was no demographic crisis, harvest crises, famines or epidemic diseases, only that the majority Amerindian populations seemed to have stabilised by the middle decades of the century and were having positive growth rates by the end of the century although of course at levels lower than in the preceding century. It is also worth noting that the Spanish, Black and Mestizo populations in this period experienced a constant increase so that despite the 16th century crisis in Indian population, total population was on the increase from the late 17th century onwardFootnote 29 .

6. SOME SIGNS OF ECONOMIC GROWTH IN SPANISH AMERICA DURING THE 17TH CENTURY

In addition to the figures we have shown, most of them related to the taxation system, there are some proxy indicators that lead us to think that the situation in Spanish America during the 17th century was not as serious as some have argued. This was a major century for church construction across the whole continent. While most churches in central New Spain were built during the 16th century, the major buildings of the northern populations of that viceroyalty date from the 17th century. Even the churches that began during the 16th century continued to be constructed during the 17th century, such as Mexico’s cathedral and the church of Santiago Tlatelolco, which was enlarged and enriched during the first half of the 17th century (De La Maza Reference Clayton1985, pp. 14-31). In South America as well, many important churches and hospitals were built during that century (see Table 2). This would appear to be another indicator of both major public and private wealth being consumed within the colonial world.

Table 2 CHURCH AND HOSPITAL CONSTRUCTION IN 17TH CENTURY SPANISH AMERICA

Source: Morales Padron (Reference Malamud1988, t. II, p. 553), Nieto Alcaide (2000), Galván Arellano (Reference Everaert1999).

Another example of this process can be drawn from receipts showing the sale of public offices. The historical literature has stressed that the selling of offices within the public administration was a reflection of the increased penury of the Spanish Crown, and that it was one of the major causes of venality and corruption in Spanish AmericaFootnote 30 . But it is also certain that in order to sell public appointments in the colonies, there had to be a local elite that had enough money to pay for those officesFootnote 31 . Among the many institutions of the Spanish Empire in the new world, municipalities were the centre towards which the local elite gravitated; local merchants, miners, landlords and manufacturers deemed buying an appointment within the Cabildo as a good investmentFootnote 32 .

By 1650 Spanish America was populated by 223 municipalities within which 2,332 posts were being sold by the crown, the total value of these offices was 4,723,487 pesos (Table 3). As the posts were sold and then renounced, this also meant a steady flow of cash for the Crown. Francisco López de Caravantes calculated the yearly income from sell of offices for the viceroyalty of Peru (which included the districts of Lima, La Plata, Quito and Santiago) in 110,000 pesos for the year 1614Footnote 33 . The sale prices well reflected the economic importance of each municipality. There were fewer municipalities in Peru (56) than in New Spain (68), but the Cabildos in the Southern viceroyalty were both large and rich: the average size of the municipalities in Peru was of 12 offices and the average price for a position was 3,862 pesos; whereas in New Spain the average Cabildo had only seven positions and a settler had to pay an average of 2,252 pesosFootnote 34 . Finally, Central America, the Caribbean and Santa Fe concentrated a large number of municipalities (99) with an average of 12 positions each, but a local resident needed just an average of 868 pesos to buy an office.

Table 3 NOMINAL VALUE OF THE OFFICES SOLD IN THE MUNICIPALITIES, C.A. 1650 (ALL VALUES IN PESOS DE A OCHO)

Source: Biblioteca Nacional de España (BNE), Raros, 3080; Biblioteca Nacional de España (BNE), Manuscritos, 3024.

The Ayuntamientos of Potosí, La Plata (Chuquisaca), Lima, Quito, Bogotá, Santo Domingo, Guatemala and Mexico had been founded during the early phases of the conquest and were the oldest and more prestigious in the AmericasFootnote 35 . Local elites sought to buy positions within those institutions as the cities were also the head of a district, the seat of an Audiencia, and — in the case of two of them — the residence of a Viceroy. The prices of the offices reflected this reality: the appointment of Alguacil Mayor de Potosí was bought by Hernando Ortiz de Vargas for 152,000 pesos in 1611Footnote 36 ; a position of Regidor entitled to vote within the Cabildo de Lima was valuated in almost 10,000 pesos; the posts in the municipality of Mexico could be sold for 467,000 pesos. Only the wealthiest local elite could pay such exorbitant sums (Table 3).

But these prestigious positions in key municipalities were not the only municipal offices sold. The myriad of villages and small cities that had been established during the late 16th and early 17th centuries commenced to grow in this period, and the Crown started to sell titles to these new municipalities. Positions in these new Ayuntamientos were not as expensive as the traditional ones, but they reflect the economic power achieved by the provincial elites: a Regidor in the municipality of Celaya — a population in the thriving agricultural region that developed south of the mining centres of New Spain — was sold for 800 pesos, whereas the Alguacil Mayor de Durango in north of that viceroyalty was offered by the Oficiales Reales for 4,000 pesos; the whole municipality of Leon was valuated in 2,370 pesos. As with the construction of churches, these receipts can be understood as a proxy for the economic wealth of the local elite of the American continent and the numbers presented here does not seem to indicate a difficult state of affairs in Spanish America for these elites (see Map 2 and Table 3).

Map 2 Value of the offices sold in the municipalities of hispanic America (C.A. 1650) Source: Biblioteca Nacional de España (BNE), Raros, 3080; Biblioteca Nacional de España (BNE), Manuscritos, 3024.

7. CONCLUSION

Thus, to answer the question of was there a generalised 17th century crisis in Spanish America, the answer appears to be no. That does not mean that there were no regional crises in production from time to time, or local harvest failures and epidemics or subsequent periods of famineFootnote 37 . But overall the production of silver from all the major mine regions of the Americas in the 17th century was stable with no declining secular trend for total volume, a factor supported by the steady arrival of silver to Europe in this same period. It would also appear that all the trade data based on royal taxation indicates a period of stability and even growth in the second half of the century. The volume and trends of the income generated from the tribute tax exclusively charged to adult Amerindian original community heads of household in this century also suggests a period of stability and in some cases growth in this same century for the Amerindian population. From this data available in the royal treasury receipts it would appear that that the severe Amerindian population decline of the 16th century had stopped by the beginning decades of the 17th century in both the Andes and in New Spain, and from alternative census materials we also know that the white, casta and African slave population were increasing in this period. So it would appear that total population was growing steadily at or above European rates of growthFootnote 38 . In contrast to Spain itself, in the colonies urban populations grew steadily in this centuryFootnote 39 . Along with that urban growth came a major era of massive church construction in the South American colonies and even a very significant sale of municipal offices to an increasingly wealthy local elite. Finally it would appear that an ever greater share of rising royal receipts from American taxation was being spent in America to defend the colonial empire and sustain all the frontier and port fortifications which effectively guaranteed the stability of the colonial empire against all European attempts to wrest control over American territory from Spain.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Carlos Marichal and Carlos Álvarez Nogal for their comments and suggestions; and the late John J. TePaske and Jacques A. Barbier for their aid in analysing the royal accounts.