1. INTRODUCTIONFootnote 1

The roots of Judaism in the Iberian Peninsula can be tracked back to the Roman period, well before the founding of Portugal and Spain. In Portugal, there is unequivocal evidence of a Jewish presence and its importance in the distant past—in the Hanukkah menorah (מנורת חנוכה), the mezuzah (מְזוּזָה) and the two stars of David (מָגֵן דָּוִד) drawn on the coats of arms of the village of Carção and the city of Leiria.

One can also find these traces in literature, in the linguistic variations of Judaeo-Portuguese inscribed in the plays of Gil Vicente (c.1465-c.1536), the literary texts compiled in chansonnier form by Garcia de Resende (1470–1536), the chronicles of Fernão Lopes (c.1389/90-c.1460); in painting, in the Rabi drawn in the Panel of the Relics by Nuno Gonçalves (c.1420-c.1490), the Jew by Vasco Fernandes; and in sculpture, in the seated Jew writing on the upper right-hand side of the tomb of King Sancho I (r.1185–1211) in Santa Cruz Monastery in Coimbra, or the prophet with the Torah and the cap at the head of the cloister of the Jeronimos Monastery in Lisbon. These are some of the many examples of how representations of Jews are portrayed in medieval and Renaissance Portugal.

From the north to the south of this southern region of Europe, we also find countless streets with names such as «Judiaria» (Jewish neighbourhood), «Judeu» (Jewish man) and «Judia» (Jewish woman). These are obvious signs of a social landscape of Sephardic origin, which, although long since disappeared, has left its mark on these places.

The recovery and systematisation of the history of the Jewish minority emerged in Portugal belatedly, initiated mainly by Alexandre Herculano (Herculano Reference Herculano1854/1859), Amador de los Rios (Amador de los Ríos Reference Amador de los Ríos1875/76) and Meyer Kayserling (Kayserling Reference Kayserling1866–67). This field of research was continued and developed in the 20th century by the historians João Lúcio de Azevedo (de Azevedo Reference de Azevedo1922) and António José Saraiva (Saraiva Reference Saraiva2001). While de Azevedo studies the origins of the Portuguese Jews, the period of persecution and immigration to Africa, Europe and America, Saraiva focuses his investigation on the inquisitorial structure, arguing that the Inquisition was a «Jewish factory» and that the Judaeo-conversos, initiators of a still incipient Portuguese bourgeoisie, were in fact victims of an aristocracy that used the Inquisition to annihilate them. This view of an aristocratic and instrumentalised Inquisition, in which the people judged were not Jewish and their confessions were the product of false accusations mixed with the perversity of an inquisitorial system that was corrupted and manipulated by an elite, is incompatible with the opinions expressed by the historian Israel Salvador Revah. Revah considers that the Judaeo-conversos were clandestine but sincere Jews, who were divided between the preservation of their traditions and religious beliefs and being forced to publicly renounce them by a dominant faith. Henry Kamen associates himself with Saraiva, defending the same theory, while the historian Bentzion Netanyahu approaches the academic thinking of Revah, disagreeing on an important point; for him, the Judaeo-conversos had betrayed their religion, which is why they could not be characterised as true Jews (Saraiva Reference Saraiva2001, pp. I–XIV). Indifferent to these controversies is Maria José Pimenta Ferro's work, which focuses on Portuguese Jewish communities and the participation of Jews in society and the economy from the medieval period to the Renaissance (Ferro Reference Ferro1979). For the first time, beyond the inquisitorial period, we have a sensitive reading of what the Jewish minority actually was, existing side by side with the Islamic minority and the Christian majority. It is through this author that we can trace the origin of the commercial rivalry between Jews and Christians, accompanied by the maritime expansion of Portugal outside Europe. More recently, new elements have emerged in Jorge Martins' work (Martins Reference Martins2006) and again in Maria José Pimenta Ferro's new publications (Ferro Reference Ferro, Lopes de Barros and Montalvo2008, Reference Ferro2014).

Several authors have written about the diaspora of Portuguese Jews around the world, including Jonathan Israel and Daviken Studnicki-Gizbert. While Israel's study identifies and locates various diasporic movements within the great Jewish Diaspora and incorporated this idea into the title of the book itself, Diasporas within the Diaspora: Jews, Crypto-Jews, and the World Maritime Empires (Israel Reference Israel2002), the historian Gizbert (Studnicki-Gizbert Reference Studnicki-Gizbert2007) studies the groups of Portuguese Jewish origin that would participate in the commercial structure of the Spanish Empire, particularly in the period of the union of crowns (1580–1640) and their involvement in the colonies' Spanish–American relations. Unfortunately, neither work covers the Jewish Diaspora in China and Southeast Asia, a gap that is partially filled by the economic approach of Boyajian (Reference Boyajian2008/1993) to the Portuguese trade in Asia, by the social approach of Uchmany (Reference Uchmany1989) and by the religious approach developed by Lourenço (Reference Lourenço2012). More recently, my own studies have shed light for the first time on the Judaeo-converso community that was established in Macao and in Nagasaki (De Sousa Reference De Sousa2010, Reference De Sousa and Nakajima2013, Reference De Sousa2015, Reference De Sousa, Perez-García and De Sousa2018b).

The present work seeks to highlight new documentation on the Jewish presence in the Macao–Philippines trade, with its links to India, Europe and America. There is little information about these Judaeo-converso communities and their members and we do not know their true sizeFootnote 2. They are only referred to when there are drastic political or economic changes, such as dynastic changes (merging of the Portuguese and Castilian crowns), opening of trade with other Asian regions (Macao–Philippines route) or tax collection (in Macao).

Through the present study, we also intend to identify the different stages of Judaeo-converso immigration to Asia; who the prominent figures of Jewish origin were, both politically and economically, in the Macao–Philippine commercial network, and what impact the Judaeo-conversos had on the European communities established in Macao and Manila during the 16th and 17th centuries.

2. THE BEGINNING OF THE JUDAEO-CONVERSO PRESENCE IN ASIA

It was in 1498, after the arrival of Vasco da Gama in India and the beginning of the Carreira da Índia, a commercial route that linked the cities of Goa and Cochin with Europe, that the descendants of the Iberian Jews began their mercantile activities in Asia. Cochin was conquered by the Portuguese in 1503 and quickly became a place of reception for Iberian Judaeo-Conversos, who co-existed with two former Jewish communities, the so-called Malabar Jews (judeus malabares) or Black Jews (judeus negros), and the Paradesi Jews (judeus Paradesi) or White Jews (judeus brancos) (Fischel Reference Fischel1956, pp. 37–57; Levi Reference Levi2003, pp. 155–176; da Silva Tavim Reference da Silva Tavim2003). The German traveller Balthazar Sprenger, arriving in Cochin in October 1506, refers to the city's Jews as having sent a letter to the rabbinic authorities in Egypt in order to receive religious advice from Rabbi David Ibn Avi Zimra (1479–1573) (Fischel Reference Fischel1962, p. 39).

Surprisingly, the initial creation of the Judaeo-converso community in Cochin was carried out by a woman, Leonor Caldeira, one of the most interesting examples of the European female initiative in Portuguese India. Born in the kingdom of Castile, at an uncertain date and place, Leonor travelled to Portugal with her family when the Jews were officially expelled from Spain in 1492Footnote 3. She presents two stories about her conversion: in the first, she claims to have been converted to Christianity in Lisbon, probably in 1497, during the mass conversion organised by King Manuel IFootnote 4; but in the second version, she states that she does not know the place where she was baptisedFootnote 5. From this point until her decision to leave for India, almost nothing is known about the first decades of Leonor's life, except that she was married to the Judaeo-converso Diogo NunesFootnote 6, who died in Europe on an unknown date. In 1535, the widow Leonor Caldeira left for Goa (India), in the armada of Fernão Perez de Andrade, with only two daughters (still children), the oldest Clara CaldeiraFootnote 7, and the youngest, Ana Caldeira, whose date of birth is not known. Arriving in Cochin that same year, she became part of the important social network that consisted of the Sephardic Jews and Judaeo-conversos living there. From at least 1529, several Iberian Judaeo-converso families had settled in the city. The Rodrigues, Olivares, Nunes, Costa, Vaz and Rodrigues «Boquinhas» families were closely associated with several Jewish families, particularly the Cairo, Moisés Real, Isaac Sul «Ruivo» and Narbona families. Their connections with important Jews, such as Abraham «branco», Abraham «preto», Jacob, Rabbi Moses, Rabbi Solomon, the Jew Jacob and the Jew Mardochai, played a decisive role in the persecution of this community.

Leonor Caldeira opened a trading house, selling fabrics and lending money to the community; she was given the nickname «confiteira»Footnote 8. Leonor represented the memory of the Sephardic traditions, knowledge that guaranteed her a central place in the community, instructing Judaeo-converso families on Jewish rituals. Her social skills made it possible to marry her two daughters Clara and Ana to important (and rich) merchants. Clara Caldeira's marriage to Luís Rodrigues was particularly relevant to the Judaeo-converso community of Cochin, because this merchant would develop the first Sephardic network linking Portuguese India with China.

Luís Rodrigues was born in Lamego (Portugal), his birth date being unknownFootnote 9, and nothing is known about the first decades of his life, except the date on which he left Lisbon for Goa: 2 April 1529Footnote 10. It is not known where he lived until he established himself in Cochin in 1549Footnote 11. Luís Rodrigues and Clara Caldeira had two daughters, Beatriz Rodrigues and Leonor CaldeiraFootnote 12. Both married the Judaeo-converso António Dias, who was a business associate of Luís RodriguesFootnote 13.

With regard to Luís Rodrigues's commercial network, we know that he was a vessel negotiator (buying and selling ships) and was also involved in maritime commerce, negotiating for the transport of goods and transporting Christian, Muslim, Jewish and Hindu merchantsFootnote 14. His investment network stretched from Cochin and Malacca to Bembar, Bengal, Cannanore, Calicut, Coulon, Cape Camorim, Ceylon, China, Coromandel, Martava, Mecca, Nagapatan, Pegu, Quedah, Siam and TenassarimFootnote 15. Luís Rodrigues had a special travel provision that had been issued by the captain of Malacca, which favoured all merchants who travelled on his vessels to that city, allowing them to monopolise the Cochin–Malacca routeFootnote 16. The issuance of this special provision meant Rodrigues had many enemies, mainly Catholic traders who were also interested in controlling the route.

In Malacca, Rodrigues's trading empire was run by the Judaeo-converso Nuno VazFootnote 17. Although we do not know the extent of his social network, it is possible to identify other Jewish and Judaeo-converso agents, namely Abraão, António de Sá, Diogo Vaz, Francisco Gonçalves, Isaac do Sul (aka «Ruivo»), Jácome de Olivares, Jorge Cardoso, Moisés Real, Rui Gomes, Simão Nunes and Simão RodriguesFootnote 18. Of this group, Jácome de OlivaresFootnote 19 stands out; he was an important merchant of Sephardic origin, the son of Antonio de Olivares (a Christian nobleman) and Violante Lopes (a Judaeo-conversa)Footnote 20; therefore, he deserves to be highlighted as, along with Luís Rodrigues, the most important Judaeo-converso who became established in India in the first half of the 16th century. Born in Setúbal on an unknown date, Jácome de Olivares travelled to India in 1540 and married the Judaeo-conversa Maria NunesFootnote 21.

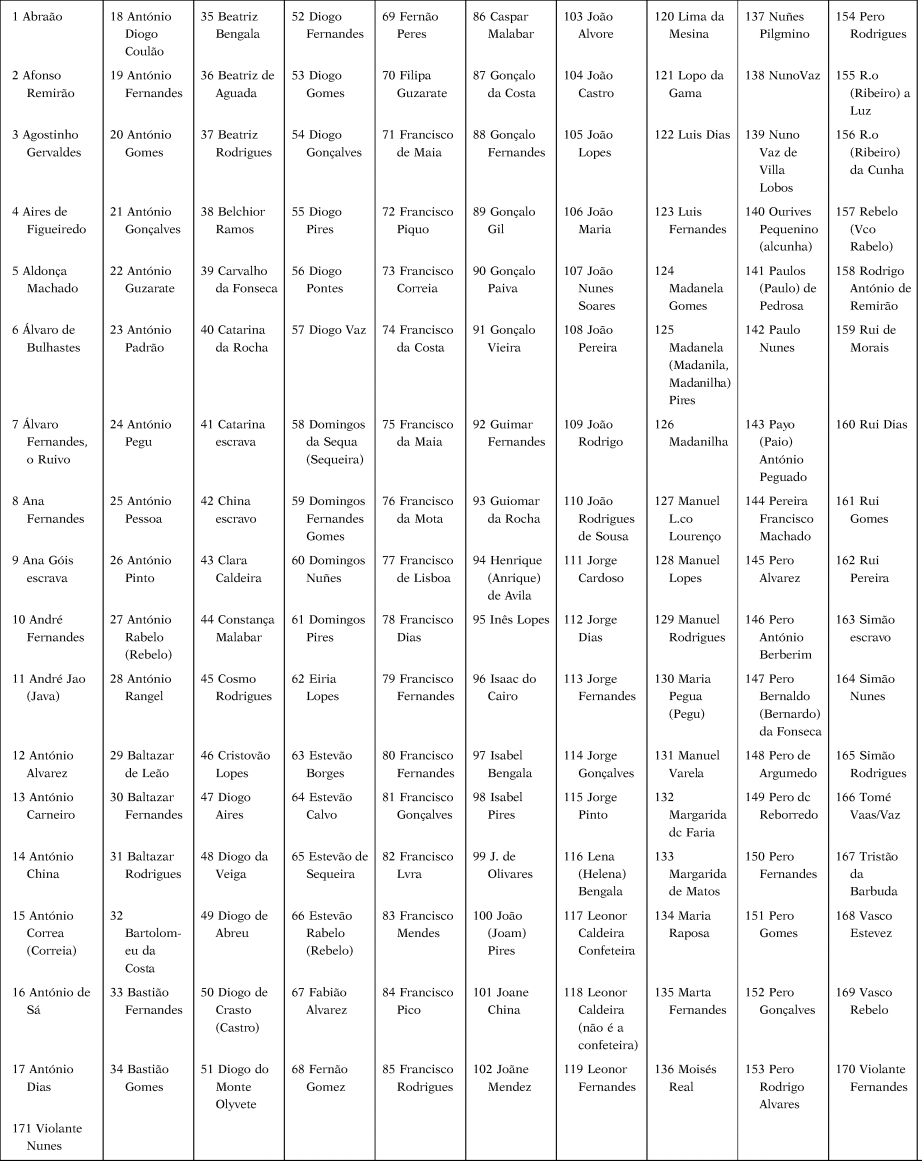

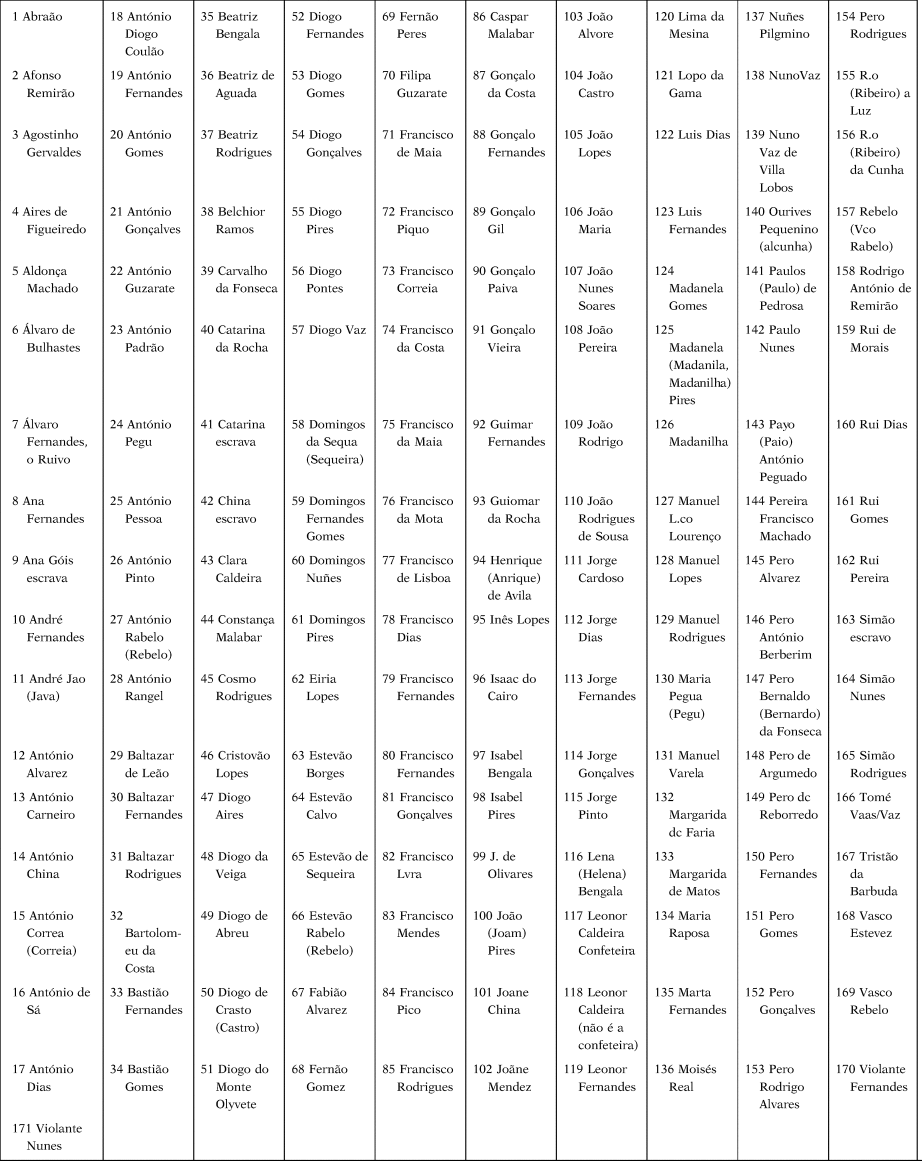

With regard to the commercial network in which Olivares travelled, it mainly centred on Malacca and the trade with China. There are also some references to the Bengal region, where he was involved in the slave trade. The main commodities he sold were Chinese silks and porcelain, china wood (pau da china) and slaves. He also had in his service a Chinese slave named Joane China/João Chin (John Chinese). These elements demonstrate the connections he had with China (De Sousa and Assis Reference De Sousa and Assis2009, p. 105)Footnote 22. Olivares's connection with Luís Rodrigues was very important because, in addition to maintaining contacts with the Portuguese political elite in India, they also established important commercial relations with Judaeo-conversos who were leading the community (see Table 1 and Figure 1).

TABLE 1. LIST OF CONTACTS OF JÁCOME DE OLIVARES AND LUÍS RODRIGUES

Source: see text.

The growing economic and political power of these two traders brought them various opponentsFootnote 23. In the case of Luís Rodrigues, these enemies knew about his donations to the construction of the Cochin synagogue (financial support for its building and textiles for its decoration), that he was helping poor Jews and Judaeo-conversos in the region and that he was always accompanied on his sea voyages by a Jewish cook, who prepared his meals according to the Jewish ritesFootnote 24. Christian merchants and nobles made accusations against him and against the Sephardic Portuguese families established in Cochin, namely the Olivares, Nunes, Costa, Vaz and Rodrigues Boquinhas families. After Rodrigues was arrested, the testimonies of thirty-four citizens (twenty-seven Christians and seven Judaeo-conversos) were recorded. They denounced the close social and economic relationship between Judaeo-conversos families and several Jewish families that had settled in IndiaFootnote 25.

The imprisonment of Luís Rodrigues and Jácome de Olivares and their subsequent dispatch to Europe coincided with the establishment of the Inquisition in Goa (1560). The main consequence of this was the destruction of Cochin's Jewish commercial network. From this network, the Jewish merchants Abraham, Isaac of Cairo, Jacob (merchant), Jacob (pepper dealer) and Moses Real, and the Judaeo-conversos Baltazar Fernandes, Baltazar Rodrigues, António Dias, Diogo da Veiga, Lopo da Gama, Nuno Vaz, Pero Alvarez, Pero Rodrigues and Rui Gomes, managed to escape to other regions, but the Sephardic community of Cochin was never able to recover, being closely watched by the Inquisition of Goa during the 16th and 17th centuries. It was also in this period of persecution, when the Inquisitorial Court in Goa was founded, that the colonisation of Macao by the Portuguese and their associates took place (1557). This constituted a new diaspora centre for Judaeo-conversos who had been outlawed by Portuguese India's religious persecutions.

3. THE BEGINNING OF THE JUDAEO-CONVERSO PRESENCE IN CHINA AND THE OPENING OF THE MACAO–MANILA TRADE ROUTE

With regard to Judaeo-conversos in Asia (from Southeast Asia to Japan) between 1543 and 1660, I have been able to identify 110 individuals so far. Of this group, the profession of only seventy-six of them is known, the rest being referred to only as Judaeo-conversos. Of those whose professions are identified, 85 per cent were traders (8 per cent were primarily commercial agents, 6 per cent were ships' captains), 6 per cent were religious, 5 per cent were soldiers/mercenaries, 1 per cent were doctors, 1 per cent were lawyers, 1 per cent encomenderos and 1 per cent spiesFootnote 26. We can conclude that the Judaeo-converso presence in this region of Asia was mostly Portuguese, since 54 per cent were recorded as such, 6 per cent as Spanish, 5 per cent either Portuguese or Spanish, 2 per cent probably Portuguese, 1 per cent either Portuguese or Macanese, 5 per cent Macanese and 27 per cent unknown. With regard to the Portuguese Judaeo-converso community, we can identify the birthplace of 53 per cent of themFootnote 27. From this sample, although it is probably a fraction of the actual number of Judaeo-conversos participating in the commercial networks linking Southeast Asia, China, Japan and the Philippines, we can conclude that the diaspora of Judaeo-conversos of Portuguese origin was mostly (97 per cent) from the centre and north of Portugal. The near absence of individuals from southern Portugal (Alto-Alentejo, Baixo-Alentejo and Algarve) can be explained by the socio-economic situation in that part of Portugal. A survey of the inquisitorial processes of the Inquisition of Évora between 1533 and 1668 verifies that only 22 per cent of the victims were merchants or worked in professions related to commerce (Coelho Reference Coelho1987).

If of this 22 per cent, which represents a sample of 1,182 individuals, we only count those people who were exclusively merchants, the number is much lower; only 450 individuals, or 8 per cent. Although commerce includes one-fifth of the professions of the victims of the Inquisition of Évora, profession categories such as shoemaking and tanning (14 per cent), textiles (11 per cent) and agriculture and livestock (9 per cent) exceed the profession of merchant (Coelho Reference Coelho1987, vol. II, pp. 365–384). This may be one of the reasons that explains the almost total lack of Judaeo-conversos from the south of Portugal in Southeast Asia, China and Japan. Another conclusion we can draw is that most Judaeo-conversos came from Viseu (16 per cent), Lisbon (13 per cent), Mesão-frio (13 per cent), Oporto (9 per cent) and Castelo Branco (9 per cent). Lisbon and Oporto were the main Portuguese economic centres in the 16th and 17th centuries; Viseu was home to one of the main Portuguese medieval Jewish communes; and Castelo Branco and Mesão-Frio are regions historically known to have received Spanish Jews. The region of Castelo Branco, along with Lisbon and Oporto, was also one of the Portuguese regions most affected by the Inquisition.

The Sephardic Jewish presence in China was only documented for the first time in the second half of the 16th century, when permission was requested from the Chinese authorities for the Judaeo-conversos established in Macao to construct a synagogue in which to pray (De Sousa Reference De Sousa, Perez-García and De Sousa2018b, p. 187). On this subject, I would like to make it clear that, irrespective of the exaggeration that this letter may include on the Judaeo-converso presence in Macao or regarding the synagogue project, there is a reference to this community which I believe is important to mention. However, this community remained essentially hidden, gaining political and economic relief only in the 1580s, when the merchant Bartolomeu Landeiro emerged in China. Of obscure origin, he arrived in India in 1559 and, after living several years in diverse Asian regions, settled in Macao around 1570, where he married and had two daughters. He also travelled to Asia with two nephews: Sebastião Jorge/Bastián Moxar and Vicente Landeiro. It is through the former that we know the family originated in Santa Iria, Portugal (De Sousa Reference De Sousa2010, pp. 16–17, 147, 245, 247–248).

In 1583, owing to his Jewish origins, Bartolomeu Landeiro's name was omitted from the report sent to Europe when King Philip II's sovereignty was accepted in MacaoFootnote 28. This did not prevent him from trying to forge an identity via Manila (in the city of Goa, his genealogy was probably well known by the Inquisition), presenting himself as a Portuguese nobleman in order to benefit economically. Landeiro's collaboration with the Society of Jesus was also extraordinary; he became one of its main economic allies.

It was from Macao that Landeiro built an extraordinary commercial network (see Figure 2), composed of Judaeo-conversos and Christians: Sebastião Jorge/Bastián Moxar, Vicente Landeiro, Moro João, Chema Rosa, André Feio, António Vaz, Anrique Borges, Melchior Correia, António Rebelo Bravo, Fernán de Sobreras, Nuno Fernández, António Garcês, António Teixeira Lobo, Damião Gonçalves and António Vieira. He was the owner of several ships, and extended his commercial network through India, Cambodia, Thailand, Ternate and Tidor, the Philippines, China and Japan. At the height of his power, Landeiro was accompanied by an army of European mercenaries (compañia de abentureros) of Portuguese and Spanish origin and provided important military services in Manila and in the islands of Tidore. In Japan, he was accompanied by his personal army, which in Macao included cavalry. In 1583, Macanese merchants transported goods to Japan in his galleon/carrack, and in that same year, Landeiro opened the Macao–Manila trade route, through his agent and nephew Sebastião Jorge, negotiating the annual voyage of a commercial ship from Macao to Manila with the Governor of the Philippines. In 1584, Landeiro travelled to Manila with two ships and, at the request of the Governor himself, rescued the Spanish colony that had been devastated by fire and was being menaced by an imminent attack from Sangleys. One of the ships, captained by his commercial agent and nephew Vincente Landeiro, on its return to China, would open the Manila–Japan sea route, docking at Hirado harbour (De Sousa Reference De Sousa2010, Reference De Sousa, Perez-García and De Sousa2018b).

FIGURE 2 LANDEIRO'S COMMERCIAL NETWORK

After the opening of the Macao–Philippines trade route, the Philippine archipelago became one of the most important economic centres for Portuguese merchants who had settled in Asia. Between 1583 and 1642, 271 ships, either Portuguese or captained by Portuguese, travelled to the Philippines (see Figures 3 and 4). These ships came predominantly from India, Southeast Asia, China and other regions where independent groups of Portuguese merchants had settled, such as Cambodia, Thailand and Conchichina. We can define this trade essentially as smuggling. Only a very small number of documentary sources have survived. However, the combination of registers from different Philippine ports, fragmented and scattered throughout Portugal, Spain, Mexico, Macao and Manila, allows us to approximate the numerical construction of these trips and to conclude that the Portuguese regions that developed the most important economic links with the Philippines were the city of Macao (between 1583 and 1642, 114 ships departed directly from Macao to the Philippines) and the city of Malacca (with 30 voyages) (Figures 3 and 4).

FIGURE 3 PORTUGUESE COMMERCIAL JOURNEYS TO THE PHILIPPINES (1580-1642)

FIGURE 4 ORIGIN OF PORTUGUESE SHIPS IN THE PHILIPPINES (1582-1621)

FIGURE 5 MAIN PORTUGUESE COMMERCIAL ROUTES IN ASIA IN THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD

4. THE JUDAEO-CONVERSO MERCANTILE NETWORK IN THE PHILIPPINES: FROM ITS FORMATION TO ITS DISINTEGRATION

The Macao–Manila trade route was born not only through the efforts of the Portuguese and Spanish merchants established in those two places (de Seabra and Manso Reference de Seabra and de Deus Manso2016, pp. 176–200), but also through an event that took place in a very different geographic space: the Iberian Peninsula. It was in this region, more precisely in the kingdom of Portugal, that on 30 January 1580 King Henrique died without heirs; he was succeeded on 15 April 1581 by King Philip II of Spain, the most direct successor to the Portuguese throne. This event was the culmination of centuries of royal policies to unify the peninsula (Yun-Casalilla Reference Yun-Casalilla2019). From this date, although the kingdoms of Portugal and Spain were in theory politically unified, in reality their administrative situations were quite different. Portuguese and Spanish administrations remained separate, as did their possessions in America, Africa and Asia. In the case of the Portuguese territories, these were administered by the Royal and Supreme Council of Portugal, whose members were exclusively Portuguese. However, this administrative division did not include the movement of people. As a consequence, there was a mass exodus of Portuguese Judaeo-converso merchants to the overseas regions of the Castilian administration. From a religious point of view, this exodus was justified by the news obtained through networks of Sephardic informers that the Spanish Inquisition, more rigorous and severe, was to spread its methods of capture and trial to the Portuguese Inquisition, and that the proceedings of the Castilian ecclesiastical courts contained evidence that many fugitive Judaeo-conversos had chosen Portugal as their destination (Bethencourt Reference Bethencourt2009).

The arrival of the Judaeo-conversos in New Spain and Peru (Castañeda Delgado and Hernández Aparicio Reference Castañeda Delgado and Hernández Aparicio1989) provoked a strong impact, first by causing a social reconfiguration of the main commercial centres such as Mexico City, Acapulco and Lima, and secondly by contributing to the economic expansion of these spaces, linking them to the Portuguese economic centres in Asia (Ricard Reference Ricard1937, p. 520; De Sousa Reference De Sousa, Perez-García and De Sousa2018b). In the Americas, despite the existence of an Inquisitorial Court in Mexico (1571), the Portuguese Judaeo-conversos had in their favour a long experience of crypto-Judaism in Europe and the local church authorities' lack of knowledge about their genealogies. While the inquisitorial activity in Portugal had been stimulated by the fusion of the crowns, the Mexican Inquisition maintained ignorance of, or at least apparent disinterest in, the Portuguese Judaeo-converso immigrants. Although it is impossible to identify the exact numbers of Judaeo-conversos who crossed the Atlantic and settled in Nueva España, it is possible to make an approximate survey of the merchants captured by the Inquisitions of Mexico between 1536 and 1690. Through this study, we were able to identify 152 traders who were born in Portugal, ninety-six traders born in Spain, forty-seven merchants born in other places and ninety-seven merchants with unknown nationality. Portuguese traders were subdivided as follows: 15 per cent from Castelo Branco, 13 per cent from Lisbon, 8 per cent from São Vicente da Beira, 5 per cent from Viseu, 4 per cent from Covilhã, 3 per cent from Caminha, 3 per cent from Guarda; the cities of Oporto, Monforte and Montemor had 2 per cent each, while the towns of São Mamede, Vila Viçosa, Sousel, Elvas, Semide, Segura, Santa Comba Dão, Sabugal, Lamego, Laens, Gouveia, Freixo de Espada a Cinta and Chacim had 1 per cent each. The origins of 28 per cent of Portuguese traders were unknown (Liebman Reference Liebman1964; Hoberman Reference Hoberman1977; Hordes Reference Hordes1980, Reference Hordes2005; Splendiani Reference Splendiani1997; Alberro Reference Alberro2004 (1988)). The geographical origins of the Judaeo-converso merchants who settled in Spanish America were predominantly the centre and north of Portugal (95 per cent); only 5 per cent were from Alentejo and there were none from the Algarve region.

Judaeo-conversos were present in the Philippines after their establishment in Macao and Japan, and they had a direct connection with the Sephardic community that had been established in Mexico (Kohut Reference Kohut1904, pp. 149–156; Cunningham Reference Cunningham1917/18, pp. 417–445; Lourenço Reference Lourenço2014, pp. 197–230). It was by the Pacific route, aboard the galleons that connected Acapulco to the Philippines that the first known Judaeo-conversos arrived in Manila, in the 1580s. The first Judaeo-conversos living in the archipelago were also victims of the Inquisition in the PhilippinesFootnote 29: the brothers Jorge Rodriguez and Domingos Rodriguez, sons of the Portuguese Diogo Rodrigues (aka Diego Rodriguez) and Violante Vaz (aka Violante Baez) (AGN, Inquisición, vol. 150, fl. 291). They were two run-of-the-mill merchants who did not belong to the Judaeo-converso merchant elite of Mexico, Macao or the Philippines. Jorge Rodriguez was born in Seville in 1564, and his brother Domingos Rodriguez was born in Portugal (place unknown). They had a sister, born in Seville, named Constanza Rios (aka Contanza Rodriguez, Constança Rodrigues) (Obregón Reference Obregón1895, p. 342), who in Mexico earned the nickname «dogmatist» (Quevedo and Amiel Reference Quevedo and Amiel2008, p. 95). Like many Judaeo-conversos, the Rodrigues/Rodriguez brothers dedicated themselves from a young age to commerce (tratantes) and, at the end of the 16th century, built an important economic alliance with the Portuguese merchant Sebastian Rodriguez (aka Sebastião Rodrigues), who was established in Mexico City. Born in 1571, in the Vila de São Vicente in the Minho region, Sebastian Rodriguez worked in Mexico together with his brothers António and FranciscoFootnote 30. Unfortunately, we are unaware of the size of the Rodrigues brothers' commercial network in the Philippines because only part of their inquisitorial records survived. However, through Jorge and Domingos Rodriguez's inquisitorial documents, it is possible to arrive at a surprising conclusion: the Judaeo-conversos appeared in the most surprising places throughout Iberian colonial society in Asia, including in the Inquisition.

During the interrogation carried out by the Inquisition in Manila, one of the notaries involved with the Rodriguez brothers was the Judaeo-converso merchant António Diaz de CáceresFootnote 31. Unknown to the inquisitorial authorities in Manila, Cáceres was not an ordinary merchant but belonged to one of the most important Iberian Sephardic families. We can trace his genealogy to the Sephardic families of Lopes, Dias, Rodrigues, Milão, Gomes and Cardoso (Cohen Reference Cohen1970, pp. 169–184; De Sousa Reference De Sousa and Nakajima2013, p. 259). His grandparents on the paternal side (António Lopes and Beatriz Dias) and on the maternal side (Francisco Rodrigues Milan and Beatriz Gomes) were part of the first generation of Jews who were converted to Christianity by the Portuguese King Manuel I.

António de Cáceres was the son of Manuel Lopes and Leonor Lopes, who originated in Santa Comba Dão. He had seven brothers, and his family network spread from Portugal to Antwerp, Mexico City, Cochin, Goa, Glückstadt, Hamburg, Macao, Manila and Pernambuco. Although they were Judaeo-conversos, a branch of the family reconverted to Judaism, merging with the Jewish Abensur family (De Sousa Reference De Sousa and Nakajima2013, pp. 229–281; Reference De Sousa2018a, pp. 305–307).

Born and raised in the Portuguese town of Santa Comba Dão until the age of ten, António Diaz de Cáceres was sent to the Portuguese court and was educated with the noble elite, similar to what had happened with his ancestors (AGI, Inquisición, Vol. 159, exp. 1, fl. 168v)Footnote 32. As an independent and wealthy merchant, António Diaz de Cáceres married Joana Lopes, with whom he had a daughter named Isabel. After the death of both his wife and daughter, he settled in Mexico, and married for a second time; his new wife was Catalina de León y de la Cueva, niece of the governor of the Nuevo Reino de León (New Kingdom of Leon), the Portuguese Luís de Carvajal y de la Cueva, who arrived at that position owing to his extraordinary military successes and is still today one of the most famous symbols of the Judaeo-converso presence in Mexico. Catherine's sister, Leonor León y de la Cueva, married another Judaeo-converso who was a close friend and associate of Cáceres, Jorge de Almeida, a rich merchant and owner of silver mines in Mexico (Adler Reference Adler1896, p. 29; Cohen Reference Cohen2001, p. 29; Toro and Hernández Reference Toro and Hernández2002, p. 349). After the wedding, Cáceres decided to live in Mexico City (Cohen Reference Cohen1970, pp. 172–175) and shortly afterwards, instead of devoting himself to the transatlantic trade, probably influenced by Jorge de Almeida, decided to invest his capital in the silver mines, moving to the region of Taxco, where he bought a mine (Cohen Reference Cohen1970, pp. 169–172). After a period of abundance and wealth, bad investments diminished his fortune, a situation worsened by the wave of persecutions and imprisonment launched by the Mexican Inquisition, in which the Carvajal family, for political reasons, became the main victim. In 1589, to recover the family fortunes (Gitlitz Reference Gitlitz2002, p. 69), António Díaz de Cáceres decided to travel to the Philippines (Liebman Reference Liebman1970, p. 171) and for this purpose he acquired the ship San Pedro/Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, property of the Judaeo-converso slave trader Manuel Gil de la Guardia, future Prosecutor of the Royal Audience (Procurador de Causas de la Real Audiência) of the PhilippinesFootnote 33. The San Pedro/Nuestra Señora de la Concepción vessel, although headed by António Díaz de Cáceres, was in reality a trading company formed by Cáceres, Antonio de los Cobos, Hernando de la Veja and Jorge de Almeida. The merchant Cáceres invested capital and labour as captain, on which he would receive a payment; Los Cobos invested capital and half the cargo; Hernando de la Veja invested 4,000 pesosFootnote 34; and Jorge de Almeida, brother-in-law of Diaz de Cáceres, invested 1,040 pesos.

In addition to these investments, the ship carried forty-five sailors in the service of Cáceres and twenty-five passengers. The latter paid 50 pesos per person. When the San Pedro/Nuestra Señora de la Concepción arrived at the port of Cavite, the authorities discovered that half of the goods it was transporting had not been declared at the Acapulco customs house, and it had therefore been travelling illegally. To avoid confiscation and arrest, Cáceres bribed the authorities and travelled to Macao, seeking a higher profit margin for his American products. Unfortunately, the local authorities there captured the ship, confiscated the merchandise and arrested Díaz de Cáceres. Shortly thereafter, he was placed in chains on board a commercial ship bound for Goa to stand trial (Uchmany Reference Uchmany1989, p. 164)Footnote 35. On the eve of his departure for India, Cáceres succeeded in bribing the prison watchman and escaped clandestinely onto another ship bound for the Philippines. At sea, discovered by the sailors, he was again arrested and, upon arriving in Manila, was to be officially turned over to the Governor and sentenced to death. Once again, his life took an unexpected turn when he was released, for unknown reasons. Cáceres did not reveal what happened in his journals or inquisitorial reports, but it is highly probable that his release was due to the timely intervention of the Portuguese merchant, Diego Hernández Vitoria, who was one of the city's most important figures and also a Judaeo-converso with whom he would maintain friendship and business ties. Shortly thereafter, Cáceres departed again for Acapulco, captaining the San Pedro/Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, accompanied by the galleon Nuestra Señora del Rosario and the galleon Santiago. On 24 November 1592, Cáceres finally arrived in Acapulco (Uchmany Reference Uchmany1989, pp. 164–165) and the following months were occupied in paying the many debts he had contracted in this commercial expedition. In 1597, Cáceres was captured by the Inquisition, and remained imprisoned until 1601, being released after paying a fine of 1,000 ducats. Upon returning to Europe, Cáceres visited Lisbon for a short time before fleeing to FranceFootnote 36. At this time, in Portugal, his most direct family, the Milão, became the main target of the Inquisition, and his brother, Henriques Dias de Milão, along with his wife, children, relatives and a Chinese slave, were imprisoned.

Surprisingly, even while living in Europe, Cáceres maintained contacts with the elite Judaeo-converso traders in the Americas, working for them as a spy. Through an extraordinary network of informants, he was able to send information about what was happening in Lisbon, Seville and Rome to places as far away as the prisons of the Inquisition in Mexico City. For example, in the late 16th century, one of the most important Judaeo-converso traders of Portuguese origin established in Mexico City was Rui Dias Nieto, who because of his economic and political power was arrested by the Inquisition. In prison, Nieto communicated with his son Diego Dias in ciphered language, Hebrew and PortugueseFootnote 37. One of these messages was intercepted by the Inquisitors, having been hidden inside a loaf of bread, and it is currently preserved in the Archivo General de la Nación (General Archive of the Nation) in Mexico City, revealing important secret negotiations between the Judaeo-conversos in Europe and Rome, and also reveals the author of the information: Antonio Díaz de CáceresFootnote 38.

As previously mentioned, in the short time Cáceres lived in the Philippines and Macao, he developed an important commercial partnership with Diego Hernández Vitoria, which led to a link with other Judaeo-converso merchants in Mexico, namely Rui Dias Neto and Bernardo de Luna. Diego Hernández Vitoria «the elder» (aka Diogo Fernandes Victória) was the most important Sephardic merchant in the Philippines in the late 16th century, being the alderman (regedor) of the city, a political position that he bought (so his genealogy was not examined by the Spanish authorities). Shielded by this political office, he publicly attempted to erase any vestige of his Jewish ancestry, yet privately he associated himself with all the Judaeo-converso merchants who had settled in China, Japan and the Philippines. This association encompassed more than just commercial relations; Vitoria also helped economically, protecting the Judaeo-conversos who were poor or on the run and simultaneously he also tried to develop a closer relationship with the Society of Jesus.

Regarding the family of Vitória, we know that he was born on an unknown date in Oporto, son of Duarte Fernandes Nunes and Geneva DinisFootnote 39. One of Geneva's grandmothers was called Marquise (Marquesa) by the Judaeo-conversos of the region, having been accused of practising Jewish rituals, and was burned by the InquisitionFootnote 40. We know that Diego Hernández Vitoria lived in Spanish America and Southeast Asia before arriving in Manila. In Malacca, one of the main centres of Portuguese commerce in Asia, Vitoria's Jewish origins were well known, and he was therefore ostracised by the resident Portuguese trading communityFootnote 41. Two of Vitoria's sisters also lived in Macao and a third relative had married a member of the Silveira commercial family of that city. Another family member, also a merchant, lived on the island of SolorFootnote 42 and a cousin named Luís Barcelos, a clove dealer, lived in Tidore (Boyajian Reference Boyajian2008/1993, p. 81). It is very probable that these relatives, or at least Luís Barcelos, were his agents. The commercial network of Vitoria extended through Mozambique, Mombasa, Cambay, Gujarat, Sindh, Bijapur, Golconda, Malabar, Ceylon, Coromandel, Bengal, Orissa, Pegu, Siam, Malacca, Moluccas, China and Japan. In these places, 89 per cent of Vitoria's investments were centred on trade with China and Japan.

It was thanks to the protection that Vitoria granted to the Judaeo-conversos living between China, Japan and the Philippines that we can list the main traders of Jewish ancestry who had settled in this region: Afonso Vaez, Diego Jorge, Francisco Rodrigues Pinto, Francisco Vaez, Góis, Luís Rodrigues (aka Manuel Fernandes), Manuel de Mora, Manuel Farias (Manuel Faria), Manuel Gil de la Guardia, Manuel Rodrigues (aka Manuel Rodrigues Navarro), Paulo Gonçalves, Pero Nabo, Pero Rodrigues, Rui Perez and Vilela Vaz (De Sousa Reference De Sousa, Perez-García and De Sousa2018b, pp. 183–218)Footnote 43. Of this group, only the merchants Manuel Farias, Manuel Gil de la Guardia and Rui Perez were captured by the Inquisition and sent to America to be tried. However, only the Portuguese Manuel Gil de la Guardia arrived alive in Acapulco and was tried by the Inquisition of Mexico. The Judaeo-conversos Manuel Farias and Rui Perez died during the journey from Manila. When the Inquisition discovered the Jewish origins of Diego Hernández Vitoria and began to spy on him in Manila, he was already seriously ill, and he passed away shortly afterwards. Until his death, owing to his political and economic influence, he was feared by the Inquisition's representatives, who neither arrested him nor confiscated his property. It was also at this time that the Inquisition representatives arrested the Portuguese Manuel Gil de la Guardia, dismantling the Judaeo-converso network in the Philippines. This last figure, too, played an important role in the political structure of Manila, as we shall explain.

Manuel Gil was born in Guarda in 1565Footnote 44, and for this reason was known among the community of Judaeo-conversos in Mexico as Manuel Gil de la GuardiaFootnote 45. He was the son of the second marriage of the merchant Fernando Gil with Filipa Rodrigues, who was also from Guarda. He had two sisters by the same father and mother: Leonor Gil and Blanca/Branca Gil. Manuel Gil also had three brothers by the same father: António Fernandes and Diego Hernandez, both residents in Guarda, and Francisco Gil, a resident of the city of ViseuFootnote 46. We even have his physical description: he was thin, short, with a reddish beard, big eyes and joined eyebrowsFootnote 47. Early in his professional career, La Guardia specialised in buying and selling slavesFootnote 48, travelling at some point to America. It was in the city of Cartagena de Indias that he formed a commercial association with Afonso Fernandez Mantua and Vicente Feleziano de Valencia, both Portuguese Judaeo-conversos Footnote 49. Using this network, Mantua transported Angolan slaves from Cape Verde to Cartagena de Indias, Vicente Feleziano de Valencia bought them in that port to redistribute them in Mexico, and Manuel Gil de la Guardia acted as a middlemanFootnote 50. In the first deal that took place, Feleziano de Valencia invested 300 ducats to buy forty-one Angolan slaves. Arriving in Mexico with the cargo, La Guardia and Feleziano de Valencia established important contacts with the family of Luis de Carvajal «el mozo», the latter being a distant family member of Feleziano's (Liebman Reference Liebman1970, p. 178, Reference Liebman1971, p. 216). After the slaves had been sold, La Guardia and Feleziano de Valencia met Antonio Díaz de Cáceres, who had just arrived from the Philippines, in AcapulcoFootnote 51. At this time, La Guardia and Feleziano de Valencia quarrelled, eventually dissolving the commercial society they had created on the eve of a trip to Peru. With the mediation of António Díaz de Cáceres, the two merchants solved their economic disputes, and La Guardia departed for the city of Mexico while Feleziano de Valencia left for LimaFootnote 52. The dissolution of the commercial society and the inquisitorial persecution of the Carvajal family, to whom he was very close, played a decisive role in the departure of Manuel Gil de La Guardia for the Philippines in 1594Footnote 53. In Manila, and hiding his Jewish origins, La Guardia gradually rose in the hierarchy of power, reaching the peak of the political career when he was officially appointed Prosecutor for Causes of the Royal Audience of Manila (Procurador de Causas de la Real Audiência). He then became protector of the Sangleyes (protector de los sangleyes)Footnote 54, whose interests he took care of by drawing up lawsuits against their enemiesFootnote 55. Despite trying to hide his Sephardic origin in the Philippines, the identity of Manuel Gil de la Guardia was discovered by the inquisitors in Mexico City, and on 10 February 1596, Luis de Carvajal «el mozo», his friend, revealed under torture the names of their Judaeo-converso relatives and associatesFootnote 56, and among them the name of Manuel Gil de la Guardia appeared. During the following months, the Court of the Mexican Inquisition, knowing his whereabouts in Manila, secretly gathered information against De la GuardiaFootnote 57. On 4 March 1597, a letter addressed to Father Maldonado, the Dominican who held the position of Commissar of the Inquisition in Manila, arrived in the Philippines, containing information on Manuel Gil de la Guardia's Jewish origin and his connections with Judaeo-converso merchants established in Mexico. He was arrested and sent to the AmericasFootnote 58.

After the death of Vitoria and the capture of La Guardia, the Judaeo-converso commercial network in the Philippines was dismantled, there being no more Judaeo-conversos to reach the same level of notoriety. With regard to the remaining Judaeo-converso traders established in Manila, being aware of the accusations and mandates of capture by the Inquisition of Mexico, they moved mainly to the cities of Macao and Nagasaki and, despite the risks, continued to negotiate in Manila. Of this group, the merchant Manuel Rodrigues Navarro stands out. He was born in 1547Footnote 59, in the city of BejaFootnote 60, a descendant of one of the most influential Portuguese Jewish families. The Navarro family, along with the Abravanel, Ibn Yahya, Negro, Hayyun/Faiam families, played important roles in the second dynasty as bankers, doctors, merchants, administrative officers (tax collectors) and even kings' councillors. The Navarro, in particular, did not take up as many royal offices as the Negro or Abravanel, making their fortune as merchants. The family gained particular economic power in the second half of the 16th century through the traders Eleázar Navarro and Moisés Navarro, father and son, who developed a profitable business network on the African coast (De Almeida and Marques Reference De Almeida and Marques2009, pp. 474–476). Manuel Rodrigues Navarro left Portugal on an unknown date and travelled to America, where he met the main members of the Judaeo-converso community residing in Mexico City. He arrived in Asia via the Pacific trade route and, after living in Manila for some time, settled in Nagasaki in the 1590s, where he lived until at least the year 1621, when we lost track of him. He was a close friend of António Díaz de Cáceres, Manuel Gil de la Guardia and Diego Hérnandez Vitória. Despite the inquisitorial persecutions in the Philippines, Navarro continued to visit the region. Of his commercial journeys, there are two extremely detailed accounts. On 11 May 1620, Navarro arrived in Cavite as captain of the ship Santo António. Asked about his religious origin, Navarro lied, stating that he was Catholic and lived in India (he actually lived in Nagasaki, on Hirado-Machi Street, near the port). In 1621, he made a second trip to Manila, transporting Japanese products. This private voyage was not recorded in Spanish sources, but is in Japanese sources (De Sousa Reference De Sousa, Perez-García and De Sousa2018b, pp. 205–206).

5. THE PEAK OF THE JEWISH PRESENCE IN MACAO

Despite the destruction of the Judaeo-converso mercantile network in the Philippines, Judaeo-converso merchants continued to be very active in the Macao–Nagasaki trade in the early 17th century, led by the merchant Pero Martins Gaio. The Jewish origins of Gaio were denounced for the first time by the Jesuit Manuel Gaspar in his letter from Macao to fellow Jesuit António Mascarenhas on 10 February 1611. In that letter, without mentioning the merchant's name, Gaspar explained Gaio's rise to power in Macao. At the same time, he criticised the fact that procurators dealing with the investments of the Society of Jesus were assisted by Judaeo-converso merchants instead of by Catholic merchants who had no Jewish background. This intervention and «bad influence» meant, he felt, that as a consequence the Jesuits were induced to practise lawlessness. To justify this accusation, Gaspar gave as an example a recent illegal trip from the port of Macao to Japan (Nagasaki), carried out under the pretext that it was transporting materials for masses and clothes (cangas), when in fact it also carried gold. This private journey had been discovered by the main merchants of Macao, and had damaged the reputation of the Society of Jesus in the cityFootnote 61. It should be remembered that at the beginning of the 17th century, any commercial voyage from Macao to Japan, other than the official annual voyage, was expressly forbidden by city regulationsFootnote 62. This controversial trip orchestrated by a Judaeo-converso merchant had taken place 2 years earlier, in 1609, and had been headed by Pero Martins Gaio; this episode is the first clue that points to his Sephardic origins.

Regarding Pero Martins Gaio, we do not know when or where he was born, or when he travelled from Lisbon to India. We do know, however, that after establishing himself in Macao, he married and had a daughter named Maria Gaia, who married Vicente Rodrigues, the son of a Portuguese merchant who was living in Nagasaki with a Japanese woman. Gaio's political and economic rise began at the time of the first procurator of Japan, the Jesuit Miguel Vaz (1563–1582). One of his main duties, as a trading agent for Vaz, was to go to Canton to trade goods on behalf of the Jesuits. When Vaz died, the prosecutors who succeeded him continued to use Gaio's services, and he became the factor of the Society of Jesus for commerce between Macao and NagasakiFootnote 63. In 1592, Gaio was already one of the main merchants in Macao, being associated with the richest man of the region, the Head Captain Domingos Monteiro. In Monteiro's testament, which began on 22 June and ended on 1 July 1592, the name of Pero Martins Gaio appeared as one of his principal men of trustFootnote 64. However, his rise to power as the most important merchant of Macao would occur only two decades later, in 1609. On that date, the suicide of the Head Captain of the cityFootnote 65, André Pessoa, caused the loss in the Bay of Nagasaki of all the goods being transported by the Portuguese merchants on the annual voyage from Macao to Japan (owing to fire and shipwreck) (Boxer Reference Boxer1950). While the rich merchants of the city (Tomás Brás, Cristóvão Soares and António Ferreira) suffered a huge economic loss, Gaio was a rare exception, remaining unscathed by this episodeFootnote 66. Strictly speaking, Pedro Martins Gaio was not carrying any of his merchandise on the city's official ship, so did not risk losing any money. Taking advantage of the loss that took place, that same year he sent a private ship with goods and gold belonging to the Jesuits, claiming to help the religious of the Society of Jesus, but actually making large profits. In fact, his future son-in-lawFootnote 67, Vicente Rodrigues, had secretly paid the Society of Jesus for the silk they had invested in which had been lost with the ship, so they had not been affected economically by the disaster; indeed, they had to hide the money and gold that had been entrusted to them by the merchants who were killed in the shipwreckFootnote 68.

Gaio's commercial network extended from India (Cochin) to Malacca, China, Japan and the Philippines. Curiously, Goa, seat of the Portuguese Inquisition in Asia, did not belong to this network and was seen as a place to be avoided. At the same time, there was an important connection between Gaio and the city of Cochin, which proved to be an important city for Macao, since its main economic figures came from that place. The Gaio family was also associated with another family of Judaeo-converso merchants: the Nassi (aka Nasi). When, in 1609, Macao merchants lost their investments in the ship headed by André Pessoa, Catarina Nassi was one of the merchants affected. Her commercial agent, Sebastião Gonçalves, invested money in her name, advised and guided by the Jesuit Manuel Dias. Because of this, the Jesuits would pay her 1,340 taelsFootnote 69. The same did not happen to another member of the Nassi family, also living in Macao, a merchant named João Bautista Nassi. He had deposited money in the Society of Jesus in Macao and this had been invested by the prosecutors in the commercial voyage of 1609. With the loss of this investment, João Bautista Nassi sought to recover the money through a judicial process against the Society of Jesus, which he later gave upFootnote 70. Besides the important economic role it played, the Gaio family also gained political relevance in Macao, as will now be explained.

6. THE «FINTA» CONFLICT: THE JUDAEO-CONVERSO TRADERS OF MACAO AND THE STRUGGLE AGAINST THE INQUISITION

The security and survival of the Judaeo-converso community in Macao, led by Pedro Martins Gaio, was at serious risk in 1611, when Gaio personally faced the representatives of the Inquisition in Macao's «Finta» conflict.

To understand the importance of Gaio in this conflict, as well as the relationship of the Inquisition of Goa with the Macao Judaeo-converso merchant traders, we need to go back to 1583, when the Head Captain Aires de Miranda elected to carry out the commercial voyage between Macao and Nagasaki, representing the interests of the Inquisition of Goa. For the first time in Macao's history, the Head Captain was ordered to capture and send all the Judaeo-conversos living in the city to GoaFootnote 71, in line with the law of King Sebastian of Portugal dated 15 and 20 March 1568 (Pato Reference Pato1884, p. 216).

Having arrived in the city, Head Captain Aires de Miranda did not carry out his plan, and the main Judaeo-conversos remained in the cityFootnote 72, revealing that the Macao merchants were powerful enough to stop the Inquisition from entering their social space. The second attempt by the Inquisition of Goa to destroy the powerful Judaeo-converso traders of Macao would occur in 1587Footnote 73, with the dispatch of Captain João Gomes Fayo, with a commission and provision from the Holy Office Court of Goa, to arrest all Judaeo-conversos practising Judaism (judaizavan)Footnote 74, and promising to give half of the property confiscated from the Judaeo-conversos to the denunciators and the other half to the InquisitionFootnote 75. In Macao, the arrival of Captain João Gomes Fayo immediately generated a major conflict, which quickly became an important revolt against him by the Judaeo-converso merchantsFootnote 76; he was forced to hide and flee the city. These two cases from 16th century Macao demonstrate the ability of the Jewish merchant elite to overturn the attempts being made by the Inquisition to dismantle the Judaeo-converso trading network in China. The Inquisition received its greatest defeat in 1604 when, after many petitions and gold, the Judaeo-conversos resident in Europe succeeded in obtaining the much-desired papal forgiveness. However, in order for this pardon to cover the Iberian Peninsula and its colonies, it was necessary to persuade the political elite to publish and enforce the papal pardon. Taking advantage of this situation, Francisco de Sandoval y Rojas, Duke of Lerma (1553–1625), representing the king, negotiated a fee of 1.7 million cruzados in order to publish the General Pardon (Perdão Geral). In reality, the amount was slightly higher, around 1.8 million cruzados, if additional expenditure is taken into account. The Judaeo-conversos of Portugal, Spain and their colonies in Asia and America proposed dividing this between themselves, and their communities settled in Portuguese India, Southeast Asia and China were obliged to pay 75,000 cruzados. In the end, while the major Judaeo-converso communities settled in the economic centres of the Habsburg Empire paid large sums of money to maintain the General Pardon, the Judaeo-converso communities in Asia did not contribute at all. In 1610, this tax was officially repealed by the king (through his representatives).

It was in the wake of these events that the newly appointed Head Captain of Macao, Diogo de Vasconcelos, was sent to China with the aim, together with a judicial magistrate (ouvidor), of conducting a survey of all the Judaeo-conversos living in the city and charging them a special tax named Finta. To clarify this episode, it is necessary to explain that a Finta was an extraordinary pecuniary tax that had been levied by the Portuguese monarchs on Jews and their descendants since the medieval period. After the expulsion and forced conversion of the Jews in Portugal, the Finta had become obsolete. With the General Pardon, it was reactivated, and merchants of Jewish origin residing in the Habsburg Empire were pressured to pay the tariff according to their level of wealth.

When the new Head Captain Diogo de Vasconcelos arrived in Macao in 1611, captaining an armada of six galleons, a full-rigged pinnace and two galiots, one of the first measures that he executed was the Finta. For that purpose, a list of Judaeo-converso traders was prepared and the most important private merchants of the city were summoned by the judicial magistrate, and on behalf of the Head Captain, and were forced to pay the tax. In total, the magistrate gathered 4,000 cruzados. Offended by this extortion, the Judaeo-converso traders, headed by Gaio, revolted and organised themselves in several groups that pursued the judicial magistrate and the Head Captain. The magistrate managed to escape, and hide in the monastery of St Augustine, but only the opportune intervention of several priests saved his life. At the same time, the Judaeo-conversos sent news of the events to Europe. The magistrate also sent a report to Europe, but unfortunately this was lost. The representative of the king, Bishop Don Pedro, sent a letter to Viceroy Don Jerónimo de Azevedo on 26 March 1612, reproving the judicial magistrate for having received the Finta. As for the 4,000 cruzados, he wrote that they should be invested in copper which, after being sent to Goa, would be used in the manufacture of artillery. As for the judicial magistrate, he should be punished in accordance with the abuses of power he had carried out in Macao. With regard to the Judaeo-conversos, the bishop gave instructions to start an investigation, and they were entitled to present their defence, which would be sent to the Judicial Court of Goa (Relação de Goa), in order to determine whether they should pay the Finta. In the end, the Judaeo-converso merchants residing in Macao were not investigated, no defence was sent to Goa and they did not pay the Finta.

Regarding Gaio, after saving the Judaeo-converso community, he also saved the Christian merchant community of Macao, which was dependent on trade with Japan. In 1612, Gaio, aboard the galleon São Filipe e Santiago, travelled to Japan as Head Captain, accompanied by the Florentine merchant Orazio Neretti as a diplomatic envoy of the city of Macao. The mission was to obtain official permission to open up trade between the city of Macao and Japan, which had been interrupted by the death of André Pessoa (1609). The mission was completed successfully, and the commercial elite of the city further developed three decades of trade relations with Nagasaki (Boxer Reference Boxer1959; Oka Reference Oka2010).

As with other Judaeo-converso traders before him, namely Luís de Almeida, Manuel Rodrigues Navarro and Francisco Rodrigues Pinto (Wicki Reference Wicki1977, pp. 342–361; Rastoin Reference Rastoin and Th. Michel2007, pp. 8–27; De Sousa Reference De Sousa, Perez-García and De Sousa2018b, pp. 183–218.), Gaio established a deep relationship with the Society of Jesus, and was included in a list of the Society's principal benefactors. The list recorded monetary donations totalling 2,000 pardaos of Reais, and publicly thanked him for «his friendship and the many services and that he did to us always with good heart and zeal» (os muitos serviços e amizades que sempre com bom coração e zello nos fez)Footnote 77. In a second list, the 300 taéis that Gaio offered to the Rector of the College of the Society of Jesus in Macao, Valentim de Carvalho, is additionally recordedFootnote 78.

Ironically, Gaio was remembered by future generations of Macanese not as a Judaeo-converso, but in another, completely unexpected, way. After his death, his body was buried in a place of prestige in the Church of St Paul, an honour reserved for the great merchants of the city. Years later, in 1699, when his grave was opened, Gaio's body was found intact, with no trace of corruption, causing much admiration among the city's residents. At that time, one of the attributions of holiness was the miraculous preservation of a body after death and burial. Gaio's body was transferred to another place inside the church, and for the following two centuries was an object of adoration by generations of Macanese, acquiring sanctity and fame (Teixeira Reference Teixeira1988, p. 29).

As for the Inquisition, after 1614, with the expulsion of the Catholic missionaries from Japan, Macao received a large number of members of the Jesuit Mission. The concerns of the Inquisition were no longer centred on the Sephardic community, but on religious conflicts among Europeans.

7. CONCLUSION

In the preliminary stages of the European presence in China and Japan, it is difficult to connect names, origins, professions and religions. Strictly speaking, the vast majority of Europeans who settled in the cities of Macao and Manila were not inscribed in the history of the Iberian presence in the East. Nevertheless, this official absence does not mean that during the period in which the Judaeo-conversos lived in Asia, they did not become relevant figures in the communities where they were living. In fact, if we start investigating the lives of Europeans who settled in Asia in the 16th and early 16th centuries, we can easily conclude that the Judaeo-converso minority was able to establish itself vigorously in Macao, Nagasaki and Manila (although they were continually threatened and sometimes separated from the mercantile communities to which they belonged by the Portuguese and Spanish Inquisitions). Notwithstanding religious persecutions fuelled by Iberian fanaticism, the Judaeo-conversos who settled in Asia embody an extraordinary example of resilience; they were responsible for building commercial networks, buying important administrative posts, serving the religious institutions that persecuted them and operating illegally within and outside the political systems that discriminated against and condemned them.

Initially, Judaeo-conversos arrived in the Far East via the Carreira da Índia; however, the conquest of the Philippines by Castile (1565–1898), with Manila as capital, opened a second route (across the Pacific).

With Luís Rodrigues, we began the Judaeo-converso epoch in Asia. This trader became the leader of the Judaeo-converso community in Cochin and actively participated in the construction of the commercial network that would link India to China in the first half of the 16th century. One of its main feats was building a monopoly of the trade route that linked Cochin to Malacca. The economic success of Rodrigues and his associates was interrupted by the intervention of the Portuguese Inquisition in 1558. After the dismantling of the Jewish community of Cochin, a large proportion of the Judaeo-conversos who had settled in Portuguese India escaped to the city of Macao (1557), this being a safer place. It was in this community that from 1570 the family of Bartolomeu Vaz Landeiro became established. It was the members of this family who organised in Macao the monarchical transition from the Avis Dynasty to the Habsburg Dynasty, opened the illegal Macao–Manila trade route and also the Manila–Japan route. Combined with economic power, the head of this family, Landeiro, built an impressive private army based on slaves and mercenaries. In 1584, he aided the governor of Manila militarily and, a few months later, began a second military expedition to Tidore.

At the same time, the Judaeo-converso Diego Hérnandez Vitoria emerged in Manila, to become the richest and most powerful merchant in the archipelago and protect the entire Judaeo-converso community in the Macao–Nagasaki–Manila economic triangle. The protection afforded to some Judaeo-conversos pursued by the Inquisition, namely António Díaz de Cáceres, Manuel Gil de la Guardia and Ruy Perez, gave away his Jewish origin.

Finally, we complete our survey with Pero Martins Gaio, a protégé of the Society of Jesuits in China and Japan and associated with Judaeo-conversos such as João Bautista Nassi and Catarina Nassi. Gaio represented and protected Judaeo-converso merchants and defended them against the attempts of the Portuguese Inquisition to dismantle the Jewish commercial community of Macao. He also carried out the peaceful resumption of Macao–Japan trade (1612), saving the main merchants of the city from ruin and guaranteeing the survival of the Macanese mercantile community in the subsequent decades.

In 1640, with the separation of the Portuguese Empire from the Spanish Empire, the waves of persecution on the American continent against Portuguese Judaeo-coversos led many merchants to travel to Asia, hoping to escape the ever-closer Inquisition.

However, this was also a period of political tensions between Macao and Manila, arising from the separation of Portugal and Spain and the end of the Macao–Nagasaki mercantile route. For this reason, the European authorities and religious institutions lost interest in the Judaeo-converso traders who had settled in Southeast Asia, China and the Far East.

Acknowledgements

This research has been sponsored and financially supported by the Japan Foundation (16K16895—Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B)) and the Open Access was sponsored and financially supported by the GECEM (Global Encounters between China and Europe: Trade Networks, Consumption and Cultural Exchanges in Macau and Marseille, 1680–1840), a project hosted by the Pablo de Olavide University (UPO) of Seville (Spain). The GECEM project is funded by the ERC (European Research Council)-Starting Grant, ref. 679371, under the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, www.gecem.eu. The P.I. (Principal Investigator) is Professor Manuel Perez-Garcia (Distinguished Researcher at UPO). This work was supported by H2020 European Research Council. This research has also been part of the academic activities of the Global History Network in China (GHN) www.globalhistorynetwork.com. I am the co-founder and co-director of the GHN, and Manuel Perez Garcia is the director and founder of the GHN.