1. INTRODUCTION

Learning more about the operation and structure of money markets in Spain during the first third of the 20th century remains a challenging task. Despite a wide range of research that has produced an equally wide literature, many questions remain unanswered. In part, this is due to a generalised lack of systematic and comprehensive data or detailed accounts on the operations conducted by banks and financial intermediaries across Spain. In addition, and mostly because the Spanish peseta was not convertible to gold during this period, Spain rarely features in comparative studies of the determinants of interest rate levels and changes. Despite the works of Martín-Aceña (Reference Martín-Aceña1985), García Ruiz (Reference García Ruiz1993) or Pueyo (Reference Pueyo2006), among others, and because interest rates were not guided, in principle, by the rationale of protecting a gold cover for the Spanish peseta, their evolution has captured little attention by the international historiography, as recently highlighted by Morys (Reference Morys2013) and Jobst and Ugolini (Reference Jobst, Ugolini, Bordo, Eitrheim, Flandreau and Qvigstad2016).

This paper contributes to fill this gapFootnote 1. To this end, I build an index of market interest rates and compare them with official interest rates charged by the Banco de España (BdE) from 1900 until 1935. In order to build this index, I resort to a number of newly accessed archival sources and combine them with both quantitative and qualitative secondary sources.

The main findings of the paper are threefold. First, before the First World War (henceforth «the War»), the money market rate and the rate at which banks rediscounted commercial paper to the public was below the official discount rate of the BdE. Second, from the summer of 1914, immediately after the international moratoria on payments, the market rate in Spain soared, reflecting the sharp liquidity shock that froze international financial markets. The money market in place until then ceased to exist. Banks suffered liquidity shortages that were transmitted to their clients by raising their rates on short-term commercial lending, and they turned to the BdE for emergency liquidity provision. From this moment onwards, the BdE rate started to operate as a floor for all commercial bank lending rates and this was made law in 1921. Third, after the War, market discount rates remained above the BdE discount rate, at an average positive spread of around 150 basis points. During some years, especially in the first half of the 1920s, short-term commercial rates remained high and nonreactive to changes in the official rate, suggesting credit rationing for commercial bills of exchange. As recently described by Comin and Cuevas (Reference Comin and Cuevas2017), this also reflects that after the War, public debt became a much more widely used money market instrument to the prejudice of short-term privately issued commercial paper, which resulted in the reinforcement of the relationship between monetary and fiscal affairs in Spain (Sabaté et al. Reference Sabaté, Gadea and Escario2006; Jorge-Sotelo Reference Jorge-Sotelo2019). Importantly, the findings of the evolution of short-term commercial bank lending rates after the War have implications for the interpretation of monetary conditions during the first years of the Great Depression in SpainFootnote 2. Observed bank lending rates suggest that monetary conditions remained tight until 1934.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 provides a brief discussion of the theory and history of the relation between money market and central bank interest rates. Section 3 discusses the impact of the War on the structure and the functioning of the Spanish money market and banking sector. Section 4 describes different data sources and methodology used to construct the resulting index and discusses its implications. Section 5 concludes.

2. MONEY MARKET AND CENTRAL BANK RATES IN THEORY AND HISTORY

During the period under analysis in this paper (1900–1935), most central banks in core economies operated what today would be called a one-sided interest rate corridor, in the sense that the floor of the corridor was either zero or non-existent—deposits with the central bank rarely paid interest. In this system, the central bank's official rate—often a discount rate on the outright purchase of eligible commercial bills of exchange—would operate as a ceiling, thus setting a maximum price for liquidity and contributing to shape expectations about the pace of interest rates (Jobst and Ugolini Reference Jobst, Ugolini, Bordo, Eitrheim, Flandreau and Qvigstad2016). With money market rates below official central bank rates, banks' access to the lending facility of the central bank tended to signal liquidity shortages in the money market. This was reflected by rising money market rates up to a point at which these would hit the central bank discount rate or even go above it. A one-sided corridor or ceiling rate, coupled with a money market freeze would then introduce incentives for banks to borrow from the «ceiling rate» of the central bank or to resume interbank lending in order to take advantage of arbitrage opportunities emerging from the spread between a high money market rate and the central bank rate (Bignon et al. Reference Bignon, Flandreau and Ugolini2012).

Through the second half of the 19th century, leading central banks had developed more active interventions in money markets with the final aim of stabilising short-term market interest rates, not only as part of their normal operation within a gold standard, but also as a response to liquidity crisesFootnote 3. This increase in interaction through discount window lending required a more precise definition of eligible collateral against which central banks were ready to lend, either through outright purchases of short-term securities (rediscounts) or through short-term advances against collateral (so-called Lombard lending, similar to today's repo operations). Eligibility of collateral for these operations was determined by a two-sided process. On the one hand, deeming a given type of collateral eligible at the discount window of the central bank would increase its market price relative to other securities, so as to incorporate its liquidity premium. On the other, the existence of a network of parties that screened collateral outside the central bank that increased the reliability of a given security would also make it more likely that it would be accepted by the central bank. For example, in the case of the London Money Market, when eligible bills of exchange reached the discount window of the Bank of England, these had already been screened by a system of discount houses that operated as a buffer between merchant banks and the Bank of England, which was the last resort of liquidity (Bagehot Reference Bagehot1873; King Reference King1936; Truptil Reference Truptil1936; Flandreau and Ugolini Reference Flandreau, Ugolini and Bordo2013). While collateral mattered, in theory, more than the counterparty that brought it to the discount window (Capie Reference Capie, Whinch and O'Brien2002), in some cases, a selection of specific counterparties was introduced by central banks as a risk-management device (Anson et al. Reference Anson, Bholat, Kang, Rieder and Thomas2019). This was also the case in France, Austria or the Netherlands where, during the mid-19th century, central bank rates coexisted with higher market rates even in the presence of an active lending facility, thus reflecting the willingness of the central bank to lend only to less risky or known counterparties (Jobst and Ugolini Reference Jobst, Ugolini, Bordo, Eitrheim, Flandreau and Qvigstad2016).

Overall, and despite changes in the precise implementation and country-specific cases, during the second half of the 19th century and the first third of the 20th century, most central banks in Europe converged towards a ceiling system (or a so-called «one sided corridor» system) in which central bank rates acted as an effective upper limit to market rates.

3. THE FIRST WORLD WAR AND ITS IMPACT ON THE SPANISH MONEY MARKET

Between 1900 and 1935, the Spanish banking system experienced important changes. From a banking sector characterised by fragmentation and regionalism, Spain moved towards a widely branched banking system that increased its dependence on liquidity provided by the Banco de España (henceforth «BdE») as the latter was progressively withdrawn from operations with the non-financial sector. This section describes the process.

3.1 Banking Structure and the Money Market Before 1914

By the turn of the century, some 25 years after it had been granted the monopoly of note issuance in 1874, the BdE had already established a network of almost sixty branches across Spain and had become the main actor in regional financial flows (Tortella Reference Tortella and Banco de1970; Anes Reference Anes and Tortella1974; Castañeda Reference Castañeda2001; Aslanidis et al. Reference Aslanidis, Herranz-Loncán and Nogués-Marco2019). In contrast, commercial non-issuing banks remained regional, and they did not extend their network of branches until the last years of the First World War and throughout the 1920s (Canosa Reference Canosa1945; Tortella and Palafox Reference Tortella and Palafox1984; Martín-Aceña Reference Martín-Aceña1985; García Ruiz Reference García Ruiz1992; Pons Reference Pons, Martin-Aceña and Titos Martinez1999). Correspondent banking played a role, but it was not an efficient alternative to the branches of the BdE when it came to bills payable in different parts of the country (Cambó Reference Cambó and Regionalista1915; Castañeda and Tafunell Reference Castañeda and Tafunell1993; Castañeda Reference Castañeda2001). Considered together, all these factors meant that, up until the First World War, the BdE was effectively a competitor to regional and local banks in most cities in Spain in a period in which there was also increasing competition between banks at the local level (Cuadras-Morató et al. Reference Cuadras-Morató, Fernández-Castro and Rosés2002). Competition from foreign banks was also strong in some cities, such as Barcelona (García Ruiz Reference García Ruiz, Sudrià and Tirado2001; Castro Reference Castro2012). Competition between the BdE and some important regional banks implied that the country lacked a unified national money market with a well-defined instrument through which banks had access to an elastic supply of liquidity at the discount window of the central bank (Ministerio de Hacienda 1921; Ceballos Teresi, Reference Ceballos Teresi1931; Prados Arrarte Reference Prados Arrarte1958).

That said, the BdE did not compete effectively in all types of credit operations and all segments of the money market; there were certain securities in which local and regional banks held an advantage, partially because they had been established before the branch of the BdE or because they were willing to embark on operations that the BdE could not provide. The case of Barcelona—where by the early 20th century banks held around two-thirds of total banking assets in Spain—but also the case of Bilbao are illustrative. Rather naturally, both being dynamic industrial regions, they had developed their own banks in the mid-19th century, and these banks had enjoyed the freedom of issuing their own notes until 1874, when the BdE was granted the monopoly of issuance (Blasco and Sudrià Reference Blasco and Sudrià2016b). The Banco de Barcelona had been founded in 1844, and the Banco de Bilbao in 1857, both as issuing and commercial banks. Also in Bilbao, the Banco de Vizcaya became an important bank; this bank was founded in 1901, as funds from the lost colonies were repatriated (Arroyo Martin Reference Arroyo Martin2002). The presence of large banks in these cities implied that the BdE did not have a comparative advantage in the local bill market and therefore it was mostly involved in the discount (and rediscount) of bills that were payable in other Spanish provinces. For the case of Barcelona, a dominant industrial city at the time, the limits of each operation and who was ready to offer it were clearer than in Bilbao. This was partially because of the nature of industry in the two regions; heavy industry dominated in the north of Spain, while the textile industry, more prone to the issuance of short-term commercial paper, most of which originated in the imports of cotton from the United States, was prominent in Catalonia.

In Barcelona, the branch of the BdE was mostly involved in the discount of bills to non-financial firms, but mostly for bills payable in other parts of Spain where the BdE had a branch established. Banks in Barcelona provided different services. First, they dominated the discount market for bills payable in Barcelona or the surrounding provinces. Sudrià (Reference Sudrià1987) highlighted the different types of bill portfolios held by Catalan banks, mainly their lack of commercial paper that could be rediscounted at the BdEFootnote 4. In fact, banks in Barcelona were very active in the money market for financial bills. In a system that is reminiscent of the current «originate and distribute» model of banking, these financial or accommodation bills were issued to securitise personal loans that banks granted to renowned industrialists or merchants and that, importantly, contained only one signature. Provided that the signature had enough reputation in the region, they would then circulate regionally (locally) as money market instruments both for merchants, banks and stock market investors (Cambó Reference Cambó and Regionalista1915; Blasco and Sudrià Reference Blasco and Sudrià2016a). This practice happened even if banking regulation, as per the Spanish Trade Code of 1885 (Article 178), stated that banks could not «rediscount bills, promissory notes or other commercial securities without these being guaranteed by two reputable signatures». In a world dominated by central banks' adherence to the so-called «real bills doctrine»—according to which they should only conduct outright purchases of bills for which an underlying real commercial transaction existed—these bills were also not eligible at the discount window of the BdE. This was not only because of their «financial» or «accommodative» nature, but also because even if the one signature they carried was included in the list of reputed signatures of the BdE, they still lacked the required second signatureFootnote 5. As these bills started circulating in the region and other, new bills were issued to replace maturing ones, effectively rolling over personal bank loans, these bills started going by the name of pelotas or papel pelota (the Spanish for «ball» or «paper ball») and the process of continued re-issuance of new bills as peloteo Footnote 6.

Importantly, Catalan banks and merchants did not only deal with bills on Barcelona and the surrounding area. Because Catalonia was the core of the Spanish textile industry, banks held a substantial amount of bills on London. These bills originated in textile firms, who imported cotton from the United States and financed these purchases by issuing bills accepted by London Acceptance Houses. Catalan banks ended up holding most of these bills, as they discounted them directly for industrialists (Cambó Reference Cambó and Regionalista1915). Therefore, while firms might have had better access to funds in order to finance their imports, these connections also exposed Catalan banks to any shock to the liquidity of the bill on London. This shock came in the first days of August 1914.

3.2 The War and Changes to the Money Market

International financial intermediation came to a halt with the outbreak of the First World War. Even before war declarations took place, stock markets had closed in most countries (in Spain, Barcelona closed, but not Madrid); central banks experienced runs on their gold reserves and were forced to suspend the convertibility of their currencies to gold, and international money markets froze (Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen1992). Despite its neutrality, which was declared on the 7th of August 1914, Spain was not immune to these developments. Money market liquidity granted by foreign bills evaporated. As a result of the cascade of international moratoria on bills of exchange, the Spanish money market froze, and banks started experiencing liquidity pressure. Importantly, and as opposed to other banking crises in Spain during this period, banks' main liquidity problems did not stem from a generalised run on their deposits. While some banks did indeed lose deposits during 1914, there was not a generalised banking panic on the depositors' frontFootnote 7.

Many banks and bankers could no longer use foreign bills denominated in sterling or other currencies to obtain liquidity. Moreover, merchants would not get their exports paid on time. Importers also suffered as international markets dried up; as explained above, for example, cotton imports from the United States were financed by bills accepted by London Acceptance Houses and this caused a sharp drop in imports of this commodity that affected important parts of Spanish industry. By early September, with the moratoria still in place, not only were banks and bankers not able to endorse bills denominated in foreign currency, but the internal market had also frozen, including the market for financial bills, the so-called pelotas. As El Liberal (11 September 1914, p. 3) reported:

«(…) internal bills have suffered a non-minor variation, and difficulties in the endorsement, because the banks have been forced to refuse infinity of operations which, until now were considered current and widely used (…)»

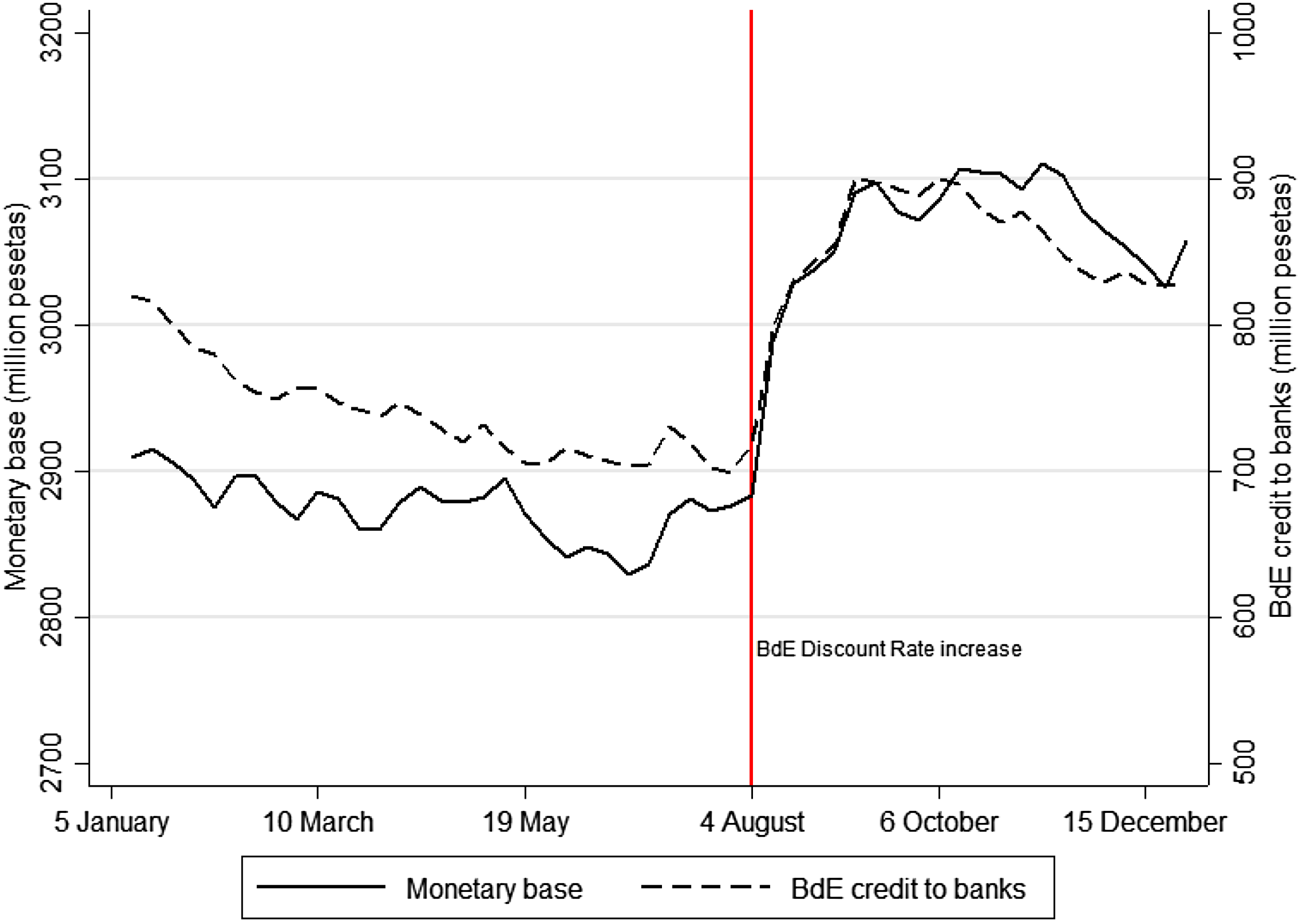

Anticipating the dimensions of the crisis, the Board of Governors of the BdE held an extraordinary meeting on the 4th of August and decided to raise interest rates. The BdE raised the discount rate for commercial bills of exchange from 4.5 to 5.5 per cent. The Lombard rate for industrial and public securities (short-term credit against these securities as collateral) was also raised to 5.5 per cent and the rate on personal credits rose to 6.5 per centFootnote 8. However, liquidity pressure suffered by banks kept increasing as it became clear that the British moratorium was going to last at least a month. Despite the rapid increase in the discount rate, banks turned to the BdE for emergency liquidity. Rediscounting and borrowing from banks at the BdE surged (Figure 1) and the Minister of Finance had to allow for an increase in fiduciary issuing 2 days after the rate was raised. At another extraordinary meeting held 2 days later, on the 6th of August, the BdE was allowed to expand its total note issuance by 25 per cent, from 2,000 to 2,500 million pesetasFootnote 9.

FIGURE 1 EVOLUTION OF THE MONETARY BASE AND CREDIT FROM THE BdE TO BANKS, 1914.

Note: Weekly figures in million pesetas. BdE credit to banks includes the stock of rediscounts, advances (Lombard credit) and personal loans outstanding at the BdE balance sheet.Source: Martínez Mendez (Reference Martínez Mendez2005).

As explained above, Catalan banks held financial bills of exchange that were not eligible at the discount window of the BdE; according to its statutes it required at least two signatures of reputed solvency to purchase a bill of exchange. If there was only one signature, then the BdE could accept the bill for rediscount only if additional securities were pledged as collateral. Accepted securities for this additional guarantee had to be backed by individuals, merchants or companies of «reputed solvency»Footnote 10. On the basis of what its statutes allowed for, the BdE also provided liquidity by lending against securities. However, given uncertainty about stock market valuations, the BdE urged its branches to accept these as collateral valued at «substantially lower values than the ones that have been recently known»Footnote 11. At the same time, however, the BdE made it very clear that haircuts charged to Lombard operations should remain secret, in order not to «affect the prestige of the collateral pledged»Footnote 12.

A similar scramble for liquidity was faced in the north of the country. Both the Banco de Bilbao and the Banco de Vizcaya asked the BdE branch in Bilbao for large rediscounts, loans against collateral and even personal credit. The branch contacted the BdE in Madrid and rediscounts of large bills or promissory notes were denied and a personal credit with the guarantee of both banks was also denied. As for Lombard credit, the BdE said it was ready to provide credit against commonly accepted securities, charging a 10 per cent haircut on the latest published market priceFootnote 13. Finally, the Banco de Bilbao was able to obtain enough liquidity from the BdE by issuing a personal guarantee for the bills it brought to rediscount. This shows that, similar to the case of Catalan banks, a large number of commercial bills held by the Banco de Bilbao did not contain the signatures that the BdE statutes required for the latter to rediscount a bill and therefore required further guarantee. As a consequence of holding a large share of non-eligible and therefore highly illiquid bills, on the 1st of September the Banco de Bilbao reported that:

«(…) had to reinforce the cash holdings, in case that the general alarm could affect the public and it could withdraw its deposits; (…) in order to prevent this, the Banco de Bilbao had managed to obtain material help from the Banco de España in Madrid, (…) and the council unanimously agreed to guarantee along with the rest of the signatories, the bills discounted at the Banco de España, and assuming any responsibility that could emerge from the operation (…)» Actas de la Junta de Gobierno del Banco de Bilbao, 1 September 1914, Libro 3, p. 279.

The reaction of the Banco de Bilbao, one of the oldest and most reputed banks in the country is illustrative of the problem the Spanish money market faced during 1914. Banks had not anticipated the need to rediscount large amounts of bills of exchange with the BdE and therefore, these only contained one signature and either matured in banks' balance sheets or circulated locally.

Collateral eligibility was not only a problem of banks in the north of Spain. The same was true in Barcelona, as described by contemporary observers including Ventosa (Reference Ventosa and Regionalista1915) and Cambó (Reference Cambó and Regionalista1915). To illustrate the shock brought about by the outbreak of the War in Barcelona, Figure 2 illustrates the changing role of the BdE in the money market in the city immediately after the freezing of financial markets in the summer of 1914. I plot the ratio between discounted bills on other provinces by the branch of the BdE in Barcelona over bills discounted by the branch on that same city. Therefore, a ratio above one implies that the branch of the BdE was more active in the discount of bills on provinces than bills on that particular city (to either banks or non-financial firms). The fragmented nature of the money market is very clear if we look at the ratio for Barcelona. Before the War, the BdE branch in that city dealt mostly with bills on provinces, while local and regional banks in the city dealt with bills on Barcelona. A sharp decline in this ratio implies that the BdE replaced banks in the rediscount of bills on Barcelona in Barcelona, lending both to banks and non-financial firms. This, in fact, can be observed from 1914, and was already highlighted by policymakers and observers at the timeFootnote 14.

FIGURE 2 THE CHANGING ROLE OF THE BdE IN THE BILL MARKET IN BARCELONA.

Source: Memorias de las Sucursales del Banco de España (various years).

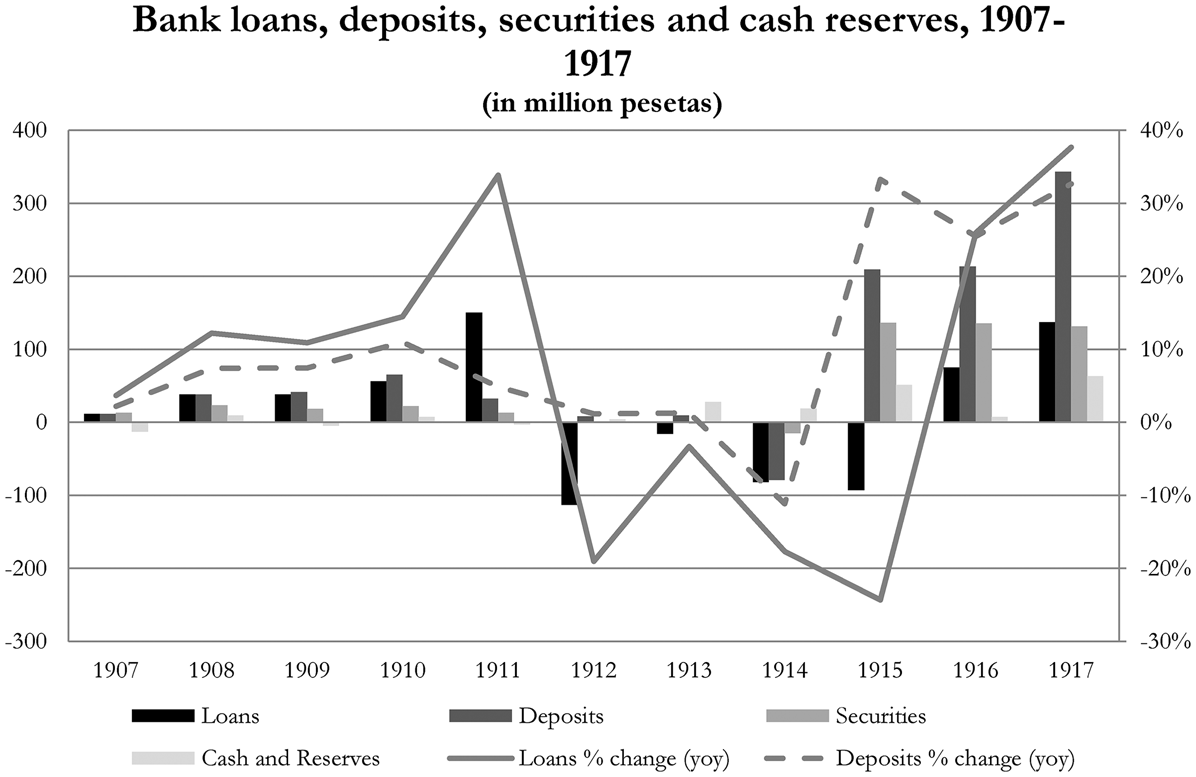

As banks suffered liquidity shortages, their lending portfolios were also affected. In aggregate terms, and to a large extent as a result of this sharp liquidity shock caused by the international moratoria, there was a contraction in bank lending in 1914, which persisted well into 1915. Figure 3 shows the evolution of total bank cash and reserves, securities, loans and deposits between 1907 and 1917 in order to place the 1914 shock in a broader context. It also shows the year-on-year percentage variation of total loans and deposits. This reveals two additional, important facts. First, the banking sector had already been experiencing difficult conditions as from 1911. This is attributable to two episodes: the impact of the Mexican Revolution on the Banco Hispano Americano (BHAM) and the collapse of the banking sector in Menorca, in the Balearic Islands. Second, the banking sector as a whole only lost deposits in 1914, although these more than recovered in 1915.

FIGURE 3 EVOLUTION OF BANK ASSETS AND LIABILITIES (1907–1917), % CHANGE AND ABSOLUTE CHANGE IN MILLION PESETAS.

Note: Figures are in million pesetas.Source: Martin-Aceña (Reference Martín-Aceña1985).

Regarding developments in Mexico, although the worst came with the failure of the Banco Central Mexicano in 1913, which caused a run on the BHAM and forced it to a temporary suspension of payments, the latter had already been under severe stress since the early stages of the Revolution (Martin Aceña Reference Martín-Aceña1984). Figures from the BHAM's balance sheet confirm this (Figure 4). The bank had to suspend payments temporarily, but deposits recovered quickly, and failure was avoided as the bank obtained an emergency loan from the BdE (Martin-Aceña Reference Martín-Aceña1984). In total, the BHAM's contraction explains 44 per cent of the aggregate deposit loss in 1914. However, it accounts for a much smaller 18 per cent of the same year's contraction in loans. Moreover, the drain on the BHAM's deposits took place during the last months of 1913 and the first months 1914, before the beginning of the War.

FIGURE 4 BANCO HISPANO AMERICANO, DEPOSITS AND LOANS (1910–1915).

Source: Balances, in Memorias del Banco Hispano Americano (several years).

Regarding the crisis in the Balearic island of Menorca, during the second half of 1911 and after a boom in lending, there was a banking panic that ended in the collapse of the financial system in the island; four banks failed and another suspended payments. Moreover, an important industrial firm dedicated to the production of machinery and automobile parts (Anglo Española de Motores, Gasogenos y Maquinaria en General), whose market extended well beyond the island into the whole Spanish territory and whose headquarters were in Madrid, also failed, as it depended on continued funding from an important bank in the island. In addition to that, banks on the island had been experimenting with the issuance of promissory notes that circulated as money in the years up to 1911. When the crisis erupted, banks were unable to convert into BdE notes on demand and a panic ensued (Casanovas Camps Reference Casanovas Camps2012).

These two episodes show that the shock to bank liquidity that took place in the second half of 1914 did not happen in complete isolation. Some important elements of the Spanish banking sector had already been experiencing problems. However, these problems were either concentrated on a very specific bank, as the case of the BHAM, or linked to a specific case of industrial failure, such as the case of Menorca. Importantly, these shocks had no significant effect on either official or market interest rates.

The events that started in the summer of 1914 were of a different nature. During the second half of 1914, banks lost their main source of interbank liquidity and scrambled for cash at the discount window of the BdE. The largest Spanish banks called back loans in large quantities, and parked whatever liquidity they could obtain from the BdE as cash reservesFootnote 15. This was the case of the Banco de Bilbao, for example. During 1914, this bank lost only 5 per cent of its deposits (1.3 million pesetas), but it contracted its portfolio of loans by 63 per cent (4.5 million pesetas) and increased its cash reserves by 70 per cent (4 million pesetas). Another bank based in the north, the Banco de Vizcaya went down a similar road; its loan portfolio contracted by 22 per cent (2 million pesetas) and it also replenished its cash reserves, although its deposits remained virtually intact. The two largest banks in Madrid saw their loan portfolios collapse; the Banco Español de Crédito's loan portfolio contracted by 57 per cent (11 million pesetas), while that of the Banco Hispano Americano, as discussed above, fell 33 per cent in 1914 (14 million pesetas), after having contracted sharply also in 1913. These two banks did indeed lose a large amount of deposits. Catalan banks also suffered liquidity shortages stemming from the moratorium, although not all fared equally. The Banco de Barcelona did not lose deposits during 1914 (there are no data at the month or quarter level); by the end of the year its current accounts had increased by more than 50 per cent. This was matched by a similar absolute increase in its cash holdings, which increased thanks to liquidity provided by the BdEFootnote 16. Banca Arnús, for example, lost 20 per cent of its deposits and contracted loans by 8 per cent, while it halved its portfolio of securitiesFootnote 17. This liquidity shock and the scramble for liquidity it caused was, naturally, accompanied by a generalised and sharp increase in interest rates in the money market. Despite the BdE's provision of emergency liquidity shown in Figure 1, the shock was so severe, that banks' short-term lending rates went above the rate of the Banco de España for the first time, where they would remain during the 1920s and 1930s.

The Banco de Barcelona increased its discount rate above the BdE rate, where it remained during the rest of 1914, 1915 and the years up to the bank's failure in 1920. This was the first time the bank's rate had risen above the BdE rate since the late 19th century and this pushed its discount rate to unprecedentedly high rates, only matched by the years of the 1882-1883 crisis (Blasco and Sudrià Reference Blasco and Sudrià2016a, p. 193). Similarly, the Banco de Bilbao raised its discount rate from 3.5 per cent to 6.0 per cent on the 8th of AugustFootnote 18. Barcelona and Bilbao are the most illustrative examples, but this was a general move:

«(…) taking into account the raise of the discount rate by the Banco de España and the current circumstances, the great majority of local Banks and savings Banks have increased their discount rate to 6% for all credit operations (…)» Madrid Científico, Año XXI, Num. 821, p. 452.

Since then, while the journal El Economista continued to provide information about the discount rate of other central banks and the official rate of the BdE, it ceased to inform about the Spanish money market rate, or «free market rate». The same journal was well aware of the far-reaching effects of the War on the money market (El Economista Reference Economista1914, p. 1160):

«After two months since the War started, we can study its consequences in our banking system, (…). We can summarize it in one phrase: we have reached a truly concentration of banks around the Banco de España. (…) There was always a certain relation between businesses, firms, industries and banking houses, but now the relationship has become something like a dependence, because it has been necessary to ask the Banco de España for help (…) not only the weak institutions but also the healthy ones (…)».

As a result of the shock, commercial bank discount rates soared above the BdE official rate as they started depending on the latter for liquidity, something that the pre-War international financial architecture—with the bill on London as the most liquid asset in the international money market—had helped postpone.

3.3 The Aftermath of the War and New Banking Legislation

The immediate financial consequences of the outbreak of the War pushed banks to gravitate around the BdE in a relation of «dependence». However, the War and its aftermath had two additional direct effects in the Spanish banking system. First, the collapse of the Banco de Barcelona in December 1920 caused an episode of major financial panic in the city (Cabana Reference Cabana2007; Blasco and Sudrià Reference Blasco and Sudrià2016a). However, and despite some local contagion through deposit withdrawals at the local level, it did not affect the rest of the Spanish banking system significantly and output remained unaffected (Betrán and Pons Reference Betrán and Pons2018). During this crisis, the BdE extended liquidity through its branch in Barcelona and initially provided help to the bank in trouble, but after it was evident that the bank was fundamentally insolvent, the BdE refused to provide more help and the bank had to suspend payments. Market interest rates increased and remained high (at around 6 per cent until 1921), but the crisis remained localFootnote 19.

The second, and more important effect for the argument of this paper, was the change in banking legislation. With the memories of the collapse of the Banco de Barcelona still fresh (the resolution of the bank was still ongoing), and the recent example of the establishment of the Federal Reserve of the United States, the Minister of Finance decided to transform the Banco de España from a large private bank that competed with banks, into a central bank. In December 1921, the Government passed the 1921 Banking Law, which had two main features regarding the relations between the Banco de España and the rest of the banking system. First, there was the intention of transforming the Banco de España into a «banks’ bank». The second feature was the creation of an institution, the Consejo Superior Bancario (CSB), in which banks could voluntarily enrol in exchange for the loss of certain privileges and by meeting certain regulatory measures (Jorge-Sotelo Reference Jorge-Sotelo2019). The CSB established minimum liquidity and capital ratios that banks had to meet. More importantly, interest rates were also limited by the CSB. While interest paid on deposits was capped depending on different deposit maturities, the discount rate that banks could charge in the market was not capped. Instead, and more importantly, a floor for interest rates was introduced. Member banks would not be allowed to discount bills in the market at lower rates than the official BdE rateFootnote 20. This represented a major change with respect to the pre-War scenario, in which large banks, in competition with the BdE, discounted bills below the BdE official rate. In short, the 1921 Law institutionalised the interest rate structure that had emerged «naturally» as a consequence of the War.

In order to achieve the progressive withdrawal of the Banco de España from competition with banks for direct operations with the public and allow it to «command the nation's credit», the law introduced a scheme of bonus rediscount rates that the BdE would apply to the banks and agricultural credit institutions that joined the CSB. The rediscount rate for CSB members would be 1.0 per cent lower whenever the official rate was above 5 per cent and would be lowered proportionally to 80 per cent of the official rate when this was below 5.0 per cent. A reduction was also applied to Lombard credit obtained by CSB banks, but this was fixed at half a percentage point over the official rate.

The 1921 Banking Law did more than setting a floor to commercial bank discount rates and introducing a bonus for rediscount rates for CSB banks. It also encouraged the use of public debt as the main money market instrument, much to the detriment of bills of exchange (Martin-Aceña Reference Martín-Aceña1984; Sabaté et al. Reference Sabaté, Gadea and Escario2006; Comin and Cuevas Reference Comin and Cuevas2017; Jorge-Sotelo Reference Jorge-Sotelo2019). In what could be called in modern parlance the establishment of a standing repo facility, the Law also forced the BdE to engage in short-term lending against public debt as collateral with all CSB member banks at their demand (individual quantitative limitations were also introduced). While the BdE still held some discretion as for which bills it could accept for rediscount, based on its own credit ratings and signature lists, it was forced to lend to banks if they brought public debt to the discount window. This increased incentives for banks to hold public debt and reduced the importance of the bill of exchange as a money market instrument. It also offered the BdE homogeneous collateral that could be used to mitigate the effects of counterparty risk that had appeared during the 1914 crisis, but also during 1920 (Cambó Reference Cambó1921, Reference Cambó1991). It also became less risky for banks to hold public debt and both lend against it to firms and borrow against it at the discount window of the BdE.

This, as could be expected, did not improve the liquidity of bills of exchange as the main money market instrument. In fact, contemporary observers became aware of the fact that in Spain, bills of exchange had not performed an important role as nationwide money market instruments because of the fragmented nature of the market and the lack of a harmonised criteria for which bills could be rediscounted at the central bank, a situation that had been in existence for several decades in countries such as Britain and France. Accordingly, Sardà and Beltran (Reference Sardà and Beltran1933, p. 65) argued that:

«(…) currently it is not possible to know either what the Banco de España discounts to private banks nor what do Catalan private banks bring to the Banco de España for discount. One is left to believe that, following the modern trend, the Banco de España is rediscounting more than previously, but it is not possible to make a clear statement on this. It would be convenient that the Banco de España clarified this when it publishes its balance sheets».

Later on, flagging the same issue, Prados Arrarte (Reference Prados Arrarte1958, p. 81) lamented «the absence of an objective criterion regarding which paper can or can't be discounted», which prevented bills from circulating widely as money market instruments, and that «the inexistence of a money market weakens the usefulness of the re-discount instrument». As a consequence, he argued, banks preferred other ways of obtaining liquidity, namely the use of the public debt standing facility established by the 1921 Banking Law.

4. DATA AND INTEREST RATE INDEX

Because of the sharp changes in the money market that took place from 1914, it is natural that the interpretation of the resulting index requires caution. I resort to three different sources for the three different periods and combine them to build a single market interest rate. However, it is worth noting that the fact that I call this rate a market rate does not necessarily mean that a nationwide liquid market existed for the securities that underlie each of the operations for which I collect interest rates, as documented aboveFootnote 21. That said, as I describe below, the series overlap for some crucial years, which suggests that the resulting index is a faithful description of the evolution of nominal commercial interest rates in Spain.

This section describes the data sources. First, I describe the data collected for January 1900 until July 1914. Second, I explain how I approximate the behaviour of market rates for the War years. Finally, I document the new sources I have accessed to build an index of market interest rates for the 1920s and the first half of the 1930s.

4.1. 1900–1914: El Economista's Descuento Libre

From 1900 until the 7th of August of 1914, every week El Economista reported the official discount rate of the Banco de España (tipo de descuento). This rate reflected the discount charged by the BdE for the outright purchase of bills of exchange in its discount window. This rate applied to all counterparties, provided that they brought eligible bills. Next to the BdE rate, El Economista reported a «free market rate» (descuento libre). It also reported the discount rate of the main European central banks and their respective market rates (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5 MARKET RATES IN LONDON, PARIS AND MADRID (1900–1914).

Source: Monthly average market interest rates, from Jobst and Ugolini (Reference Jobst, Ugolini, Bordo, Eitrheim, Flandreau and Qvigstad2016).

The types of operations captured by the «free market rate» are not detailed in the source and remain open for further research as, unfortunately, this area has not yet been documented systematically. While in other countries, which were also reported along the Spanish rates, these market rates reflected the rate at which banks rediscounted bills to each other in the free market, the exact maturity, origin and the exact type of bill that was traded at this «free market» rate in Spain has yet to be described accuratelyFootnote 22. This has been a perennial challenge for the historiography of this period, and it requires a research exercise that falls beyond the scope of this paper. However, there are some insights that can be offered by a preliminary, yet informative statistical exercise. In order to gauge the degree of Spain's integration with international financial markets—and thus in the wave of financial globalisation that took place until 1914—we need to know the degree of correlation between Spanish and international market rates.

Table 1 shows the correlation coefficients between the main money market rates in Europe and the Spanish «free market rate», and Figure 5 shows the evolution of the official BdE discount rate, the «free market rate» in Spain, and the London and Paris ratesFootnote 23.

TABLE 1 CORRELATION COEFFICIENTS BETWEEN DIFFERENT MONEY MARKET RATES (MONTHLY, JANUARY 1900–JULY 1914)

Note: All correlations are statistically significant at the 1.0% level.

Source: Calculated using data from Jobst and Ugolini (Reference Jobst, Ugolini, Bordo, Eitrheim, Flandreau and Qvigstad2016)

The London/Paris coefficient of correlation for the whole period is 0.77, the Madrid/London figure is 0.48, and that of Madrid/Paris is 0.58. Taking into account that the correlation coefficient between the two centres of the European money market (London and Paris) is only 0.77, these figures seem to suggest that market rates in Spain were, to a significant extent, determined by international rates, thus pointing towards a relatively high degree of financial integration and participation in the financial globalisation process most of the world underwent before 1914. Amongst the main European financial centres included in Table 1, it is clear that all other markets are more integrated than Spain, and that, besides the London/Paris case, there are some pairwise cases of very high integration, such as Paris/Brussels or Vienna/Berlin. However, the lower correlations for Spain hold despite the fact that the peseta ceased to be convertible to gold in the late-19th century (Figure 5).

To a significant extent, therefore, prevailing market rates in Spain were affected by international monetary conditions. As discussed above, this suggests that the «free market rate» reported by El Economista reflected the market rate of bills payable in gold-convertible currencies (presumably in London or Paris) circulating in Spain plus/minus an exchange rate risk premium attributable mostly to the non-convertibility of the Spanish peseta into gold and the subsequent fluctuations it experienced during the period. At the same time, however, Figure 6 shows that the market rate in Spain never went above the rate of the BdE. This did not happen despite the wide fluctuations suffered by other rates. This suggests that when market conditions tightened in international markets, Spain might have enjoyed some room for monetary autonomy in order to keep market rates from following the volatility exhibited by international rates and thus allowing for adjustment of the exchange rate.

FIGURE 6 OFFICIAL AND MARKET RATES, JANUARY 1900-JULY 1914.

Source: For the «free market rate», El Economista, weekly data, from the first week of 1900 to 31 July 1914. For Banco de Bilbao, Actas del Consejo de Administracion del Banco de Bilbao (L.1-L.3). For Banco de Vizcaya, Actas del Consejo de Administracion del Banco de Vizcaya. For Banco de Barcelona, Blasco and Sudrià (Reference Blasco and Sudrià2016a).

I complement this pre-War index by including the commercial discount rate of the two most important banks of the period outside Madrid. These are the Banco de Bilbao and the Banco de Barcelona, both founded in the mid-19th century and providing strong competition to the branches of the BdE in their respective regions. I also include data from the Banco de Vizcaya although data in this case is less systematic. While the Banco de Bilbao and the Banco de Barcelona were very active in discounting bills and had considerable expertise in this area of business, the Banco de Vizcaya was founded in 1901, and despite rapid expansion, it was mostly focused on industrial securities (Arroyo Martin Reference Arroyo Martin2002; Blasco and Sudrià Reference Blasco and Sudrià2010, Reference Blasco and Sudrià2016a). It is not surprising that, in the case of the Banco de Bilbao and the Banco de Barcelona, their discount rates were never above the rate of the BdE, while the rate charged by the Banco de Vizcaya converged with the BdE over time. In addition, and given their expertise in the bill market, these banks charged lower rates for the purchase of bills of exchange than for short-term loans against collateral, whereas the Banco de Vizcaya did the opposite, charging higher rates for purchasing a bill from a firm than lending against industrial securitiesFootnote 24. These rates reflect the discount of bills on the city where these banks were located.

On average, the spread between market and BdE rates was around 50 basis points before the War. Therefore, it is fair to argue that before 1914, the rate of the BdE can be taken as a reference rate to approximate short-term borrowing costs in Spain. In addition, some mechanism of interest rate management seems to have been in place, as the market rate in Spain followed the rates in London and Paris but was capped by the rate at the BdE. Tightening market conditions seem to have been eased by well-timed liquidity injections in the Spanish market. This situation changed with the outbreak of the War.

4.2 1914–1919: Banco de Bilbao and Banco de Vizcaya's Reaction to the War

As soon as Britain declared war on Germany and started mobilisation, the Spanish money market dried up, like all markets in Europe. However, because there were no moratoria of payments declared in Spain, firms and banks continued to need short-term liquidity to face their payments. As El Economista put it, relations between the banking system and the BdE had suddenly become more intense. Despite the fact that the limit on notes issued was increased on the 5th of August 1914, a day after Britain declared war on Germany, the BdE had to resort to further action and raised its discount rate 3 days later (Martín-Aceña et al. Reference Martín-Aceña, Martínez-Ruiz, Nogués-Marco, Ögren and Øksendal2013). The BdE raised the discount rate from 4.5 to 5.5 per cent on the 8th of August and kept it at that level until the 5th of September, when it cut it to 5.0 per cent. On the 26th of October, it reduced it again to the pre-War level of 4.5 per cent.

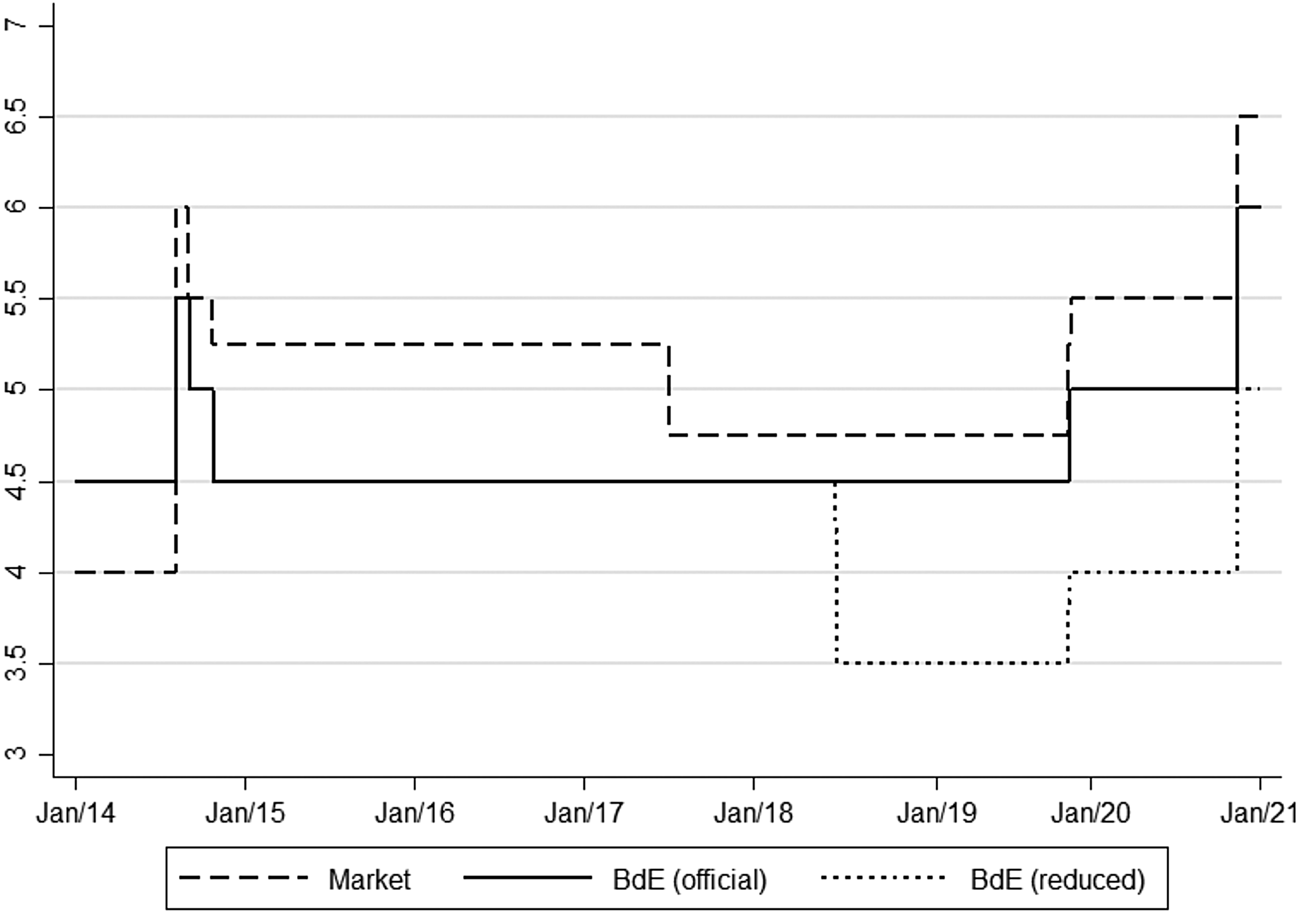

For the period August 1914 until December 1918, I obtain market discount rates from a different source: the minutes of the board of the Banco de Bilbao (Actas de la Junta de Gobierno del Banco de Bilbao) and the Banco de Vizcaya (Actas del Consejo del Banco de Vizcaya). These banks' boards held regular weekly meetings and reported changes in the discount rate as well as commenting on the reasons for these changes. The Banco de Bilbao reported rates more frequently than the Banco de Vizcaya. This implies that for the latter, I could only observe the rate change that took place on the 7th of August 1914, while the former continued to report rates throughout the War years. Both banks' rates jumped to 6 per cent due to the initial War shock, but after that, the rate I report can only be attributed, stricto sensu, to the Banco de Bilbao. While this is a limitation in terms of making this rate comparable to that reported for 1900–1914, it also shows that series of interest rates for the Banco de Bilbao and the Banco de Vizcaya do overlap between the two periods (1900–1914 and 1914–1919). In total, the discount rate changed four times between the outbreak of the War and 1919 and followed the same pattern as the official rate of the BdE: first a sharp increase and then a progressive decline. Interestingly, in 1914 the market rate rose above that of the BdE for the first time and never fell below it again (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7 MARKET AND BdE DISCOUNT RATES DURING THE WAR (1914–1920).

Source: El Economista, Actas de la Junta de Gobierno, Banco de Bilbao and Actas del Consejo de Gobierno del Banco de Vizcaya.

Before the 7th of August of 1914, the Banco de Vizcaya discounted bills of exchange at 4.5 per cent if their maturity was below 1 month and at 5 per cent if it was up to 3 months (it also charged different rates depending on the solvency of the signatures)Footnote 25. On the 7th of August, it raised its discount rate to 6 per cent for all types of billsFootnote 26. The Banco de Bilbao followed the same pattern; it had been discounting below the official rate for the whole pre-War period, almost constantly at a 3.5 per cent rateFootnote 27. On the 7th of August, it also raised its discount rate to 6 per cent, given the «abnormal situation of the European market and given the rise in the discount rate of the Banco de España»Footnote 28. A month after the rise, on the 3rd of September, the Banco de Bilbao cut its discount rate to 5.5 per centFootnote 29. Finally, on the 5th of July 1917, it cut the discount rate again to 5 per cent on bills over Bilbao and 4.5 per cent on bills over other citiesFootnote 30.

How representative is the interest rate index during the war years? As opposed to the pre-War rate, or the post-War rate, this index only represents interest rates in one region of Spain. In fact, the exact meaning of this rate is very likely not reflecting the same type of operation as that captured by the «free market rate» rate reported by El Economista. The traditional «free market rate» had ceased to exist, along with the market in the shape it had before the War. Other countries in Europe, mostly southern and eastern Europe, experienced similar shocks after 1914, and the market rates reported for these countries for the interwar years are similar to those reported hereFootnote 31.

4.3 1920–1935: Banco de Bilbao Branches’ Annual Reports

In order to build a representative index of short-term and long-term interest rates for the post-War period (1920–1935), I resort to the Annual Reports of the branches of the Banco de Bilbao (Memorias de las Sucursales del Banco de Bilbao), the third largest non-issuing bank in Spain at the time. Most of these documents report information about rival banks in the city where the bank had established a branch. The bank reported rates for most of the largest banks in Spain at the time: Banco Hispano Americano, Banco Español de Credito, Banco de Vizcaya, Banco Urquijo de Madrid and Banco Central, among others. This implies that the interest rate index I calculate for this period does, to some extent, overlap with the one I calculate for 1914–1920, because the latter is obtained from the discount rate charged by the Banco de Bilbao and the Banco de Vizcaya, and thus is comparable to the interest rate index calculated for 1921–1935. The Memorias also reported observed interest rates charged by some of these banks for different types of operations, including the discount of commercial bills of exchange on that city, bills on other cities, financial and other types of loans. Memorias are available for a total of forty-three cities in Spain. After examining all reports for all years available, I was able to obtain data from fourteen cities.

Because of the large variation of data availability for different cities and towns, I calculate four different indexesFootnote 32. First, I calculate the average market discount rate including all observations available for each year. Second, I plot the average rate between Barcelona and Madrid. Finally, I plot two additional weighted average market rates. For the first one, the weights are determined by the relative size of the commercial bill market in each city or town. This is proxied by the share of the commercial balance sheet of the BdE in the city or townFootnote 33. A second weighted index is calculated with the total number of interest rate observations for the whole period for each city or town. Hence, if a city only reports one interest rate for one bank in only 1 year, its relative importance is reduced compared to a city for which more rates are reported.

Figure 8 shows the four different indexes against the official BdE rate for CSB member banks. The exact spread between the market and the official rate varies depending on the index. Perhaps more important is the fact that despite the fact that the BdE lowered its rediscount rate during the first half of the 1920s, the market rate was nonreactive, and the spread between the two rates widened as short-term funding for firms issuing commercial paper remained expensive. Giving more weight to the operations conducted in Barcelona and Madrid naturally reduces the spread, as it is plausible that liquidity was more readily available in larger cities and for bills on these cities. This, however, also suggests relatively little financial integration in the commercial bill market, as explained above.

FIGURE 8 MARKET AND OFFICIAL COMMERCIAL DISCOUNT RATES DURING THE INTERWAR PERIOD (1921–1935).

Source: Memorias de las Sucursales del Banco de Bilbao and Actas de la Comisión Ejecutiva del Banco de España.

This index also reveals important information about the early 1930s. The spread between BdE rates and market rates started to narrow only in 1931, when the BdE raised its discount rate and the CSB rate bonus was halved (Martín-Aceña Reference Martín-Aceña1985; Jorge-Sotelo Reference Jorge-Sotelo2019). Interestingly, and despite the fact that the BdE started cutting rates in 1932, market rates remained high until 1933, when they started falling and converging rapidly with the BdE rate. This, as I discuss below, suggests that monetary conditions, especially the cost of short-term credit for final borrowers did not ease during the Great Depression.

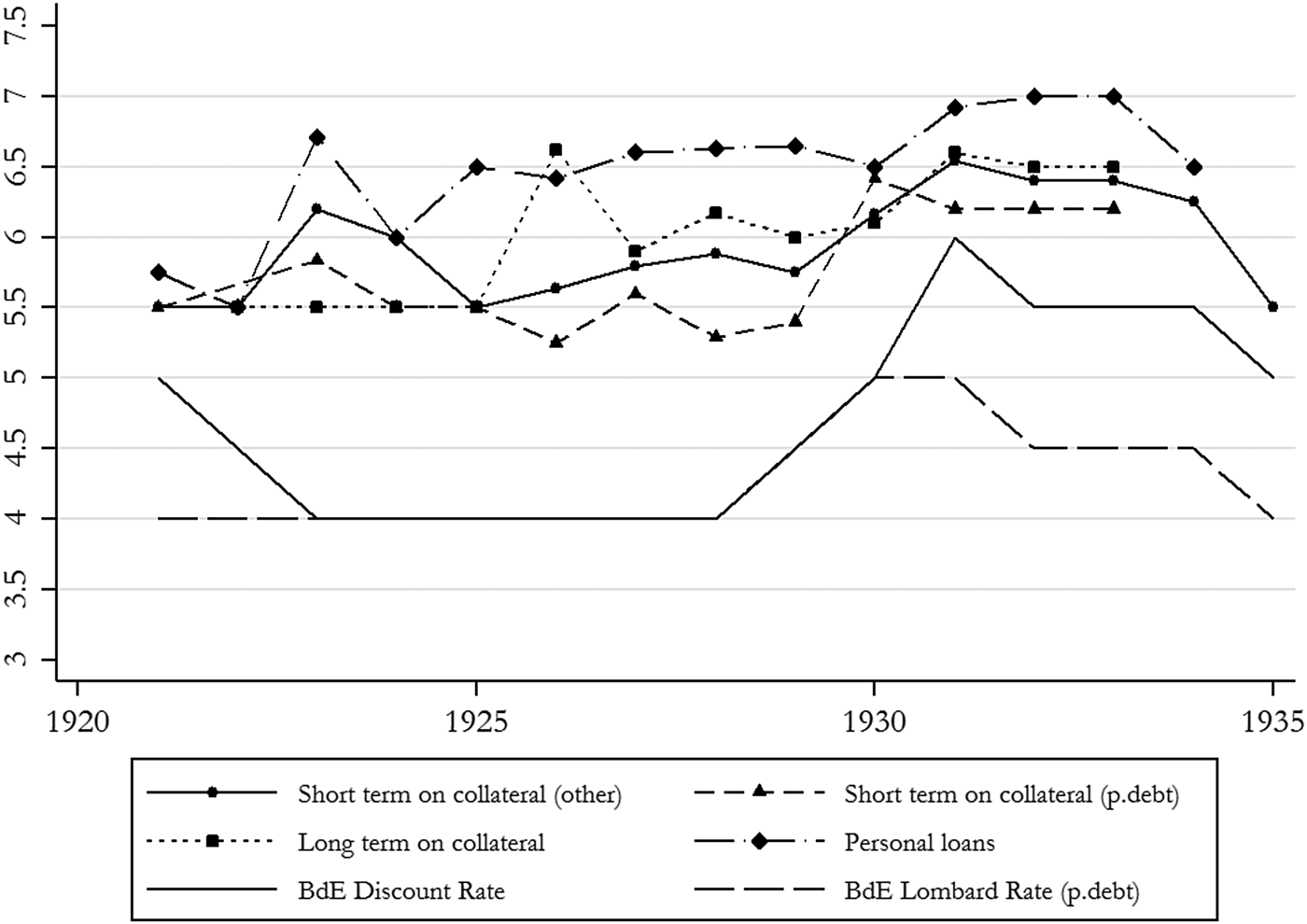

4.4 Other Rates

Besides the market discount rate, the Memorias also reported other lending rates. Compared with the frequency of the discount rate on commercial bills, other rates are reported much more sparsely. These include short-term credit on collateral (Lombard loans) for which two rates are reported for two different types of collateral: industrial securities and public debt. Longer-term loans on collateral and personal loans are also included. Simple averages of these interest rates are reported in Figure 9. I also include the two main short-term rates charged by the BdE, the discount rate and the Lombard rate on public debt (short-term credit on collateral).

Naturally, rates on personal loans and long-term loans on collateral are higher than short-term rates for the whole period (except for the first 4 years). Short-term credit on collateral, particularly when collateralised by public debt, exhibits the cheaper rates, even comparing it with the discount rate charged on commercial bills of exchange (as represented in Figure 8). This is, in fact, the result of the 1921 Banking Law, which made public debt the preferred money market instrument against which firms, banks and the BdE would borrow (and lend). As with the rest of interest rates discussed above, these rates also remained high during the early 1930s, and only started falling significantly after 1933, while the BdE had already started to cut rates in 1932.

The resulting series suggest that Spanish monetary authorities were involved in a policy of active monetary management that kept market interest rates capped at the BdE level before 1914; although more research is needed on this front, these interventions might be in line with those conducted by the Portuguese or the Austro-Hungarian central banks during the same period (Reis Reference Reis2007; Jobst Reference Jobst2009). Therefore, up until the outbreak of the War, the BdE rate can still be taken as a relatively accurate and conservative measure of the prevailing short-term cost of borrowing for firms. However, revisiting prevailing interest rates during the 1920s and 1930s reveals important changes to our understanding of monetary conditions during the interwar period and the Great Depression in SpainFootnote 34. Combining the index provided in this paper with inflation data from Comín (Reference Comín2012), the implication is that during 1931, 1932 and 1933, Spanish firms' borrowing costs hovered around a real interest rate very close to 9 per cent. This is true for both discounting bills of exchange and for obtaining loans against public debt from banks. Other types of loans, such as personal loans or long-term loans on collateral exhibit even higher real rates. Importantly, and in parallel to high real interest rates, Spain witnessed a sharp and persistent contraction in bank lending during 1931–1935; by the end of 1934, bank loans were 15 per cent below their 1930 value despite the fact that the banking system had recovered almost all the deposits it had lost during the 1931 crisis (Jorge-Sotelo Reference Jorge-Sotelo2020). Overall, evidence presented in this section suggests that monetary conditions in Spain became and remained tight during the 1930s.

5. CONCLUSION

Before the outbreak of the War the Spanish money market was integrated with international financial markets. The market rate in Spain followed the rates in London and Paris but it was never above the BdE rate. This highlights two things. First that the BdE operated in a way that resembled the traditional European central banking system before the War; its lending rate operated as a ceiling rather than a floor. The War and the international moratoria of payments caused a liquidity squeeze and market rates went above BdE rates. In parallel, the dependence of the banking system on the BdE increased. During the War, but mostly after 1921, banks started borrowing from the BdE mainly by using public debt, and the latter crowded out commercial paper from bank balance sheets. During this process the BdE discount rate became—by law—a floor, rather than a ceiling, for market rates. Finally, evidence presented here points to tight monetary conditions, a high real cost of credit and a general increase in the costs of financial intermediation in Spain during the worst years of the Great Depression.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0212610920000154.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to Olivier Accominotti and Stefano Ugolini for their comments on previous drafts of the paper. I also benefited from discussions with Yolanda Blasco, Carles Sudrià, Angeles Pons and from the comments and suggestions from three anonymous referees. Data were collected with the help of archivists Virginia García de Paredes and Gema Hernández (Banco de España), José Antonio Gutiérrez and Maite Gómez (Banco Santander) and Victor Arroyo, Gorka Fuente and Borja Fernández (BBVA). Funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) is gratefully acknowledged. All remaining errors are mine.