No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

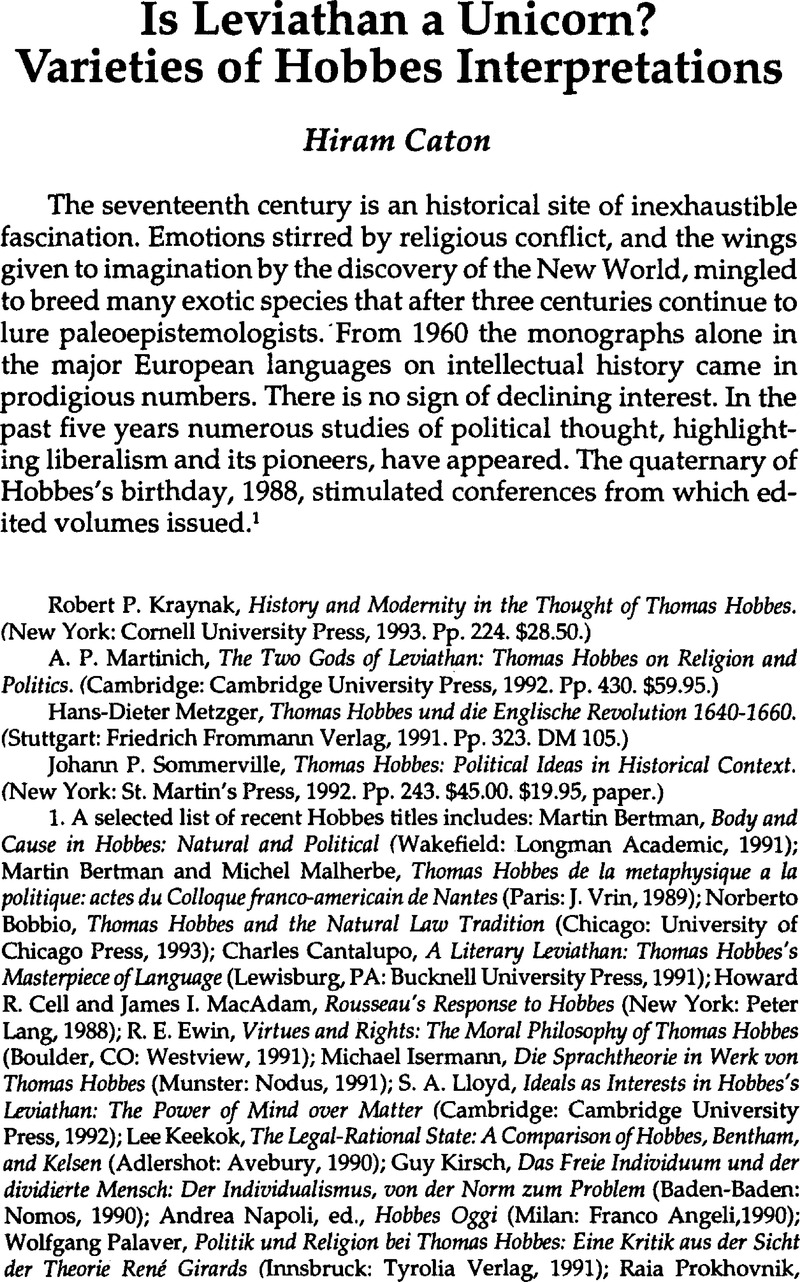

Is Leviathan a Unicorn? Varieties of Hobbes Interpretations

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 August 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © University of Notre Dame 1994

References

1. A selected list of recent Hobbes titles includes: Berrman, Martin, Body and Cause in Hobbes: Natural and Political (Wakefield: Longman Academic, 1991);Google ScholarBertman, Martin and Malherbe, Michel, Thomas Hobbes de la metaphysique a la politique: actes du Colloque franco-americain de Nantes (Paris: J. Vrin, 1989);Google ScholarBobbio, Norberto, Thomas Hobbes and the Natural Law Tradition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993);Google ScholarCantalupo, Charles, A Literary Leviathan: Thomas Hobbes's Masterpiece of Language (Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 1991);Google ScholarCell, Howard R. and Macadam, James I., Rousseau's Response to Hobbes (New York: Peter Lang, 1988);Google ScholarEwin, R. E., Virtues and Rights: The Moral Philosophy of Thomas Hobbes (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1991);Google ScholarIsermann, Michael, Die Sprachtheorie in Werk von Thomas Hobbes (Munster: Nodus, 1991);Google ScholarLloyd, S. A., Ideals as Interests in Hobbes's Leviathan: The Power of Mind over Matter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992);CrossRefGoogle ScholarKeekok, Lee, The Legal-Rational State: A Comparison of Hobbes, Bentham, and Kelsen (Adlershot: Avebury, 1990);Google ScholarKirsch, Guy, Das Freie Individuum und der dividierte Mensch: Der Individualismus, von der Norm zum Problem (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 1990);Google ScholarNapoli, Andrea, ed., Hobbes Oggi (Milan: Franco Angeli, 1990);Google ScholarPalaver, Wolfgang, Politik und Religion bei Thomas Hobbes: Eine Kritik aus der Sicht der Theorie René Girards (Innsbruck: Tyrolia Verlag, 1991);Google ScholarProkhovnik, Raia, Rhetoric and Philosophy in Hobbes' Leviathan (New York: Garland, 1991);Google ScholarSchwengel, Hermann, Der kleine Leviathan: Politische Zivilisation um 1900 und die Amerikanische Dialektik von Modernisierung und Moderne (Frankfurt a/Main: Athenaum, 1988);Google ScholarState, S. A., Thomas Hobbes and the Debate over Natural Law and Religion (New York: Garland, 1991);Google ScholarStones, James R., Common Law and Liberal Theory: Coke, Hobbes, and the Origins of American Constitutionalism (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1992);Google ScholarWalton, C. and Johnson, J. P., eds., Hobbes's Science of Natural Justice (Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1987);CrossRefGoogle ScholarZarka, Yves Charles, Thomas Hobbes: philosophie primiere, theorie de la science et politique (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1990).Google Scholar An extensive review of the Hobbes literature is to be found in the notes of Reventlow's, Henning GrafAuthority of the Bible and the Rise of the Modern World (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985; original German publication 1980), pp. 524–38.Google Scholar

2. The historiographic debate had a philosophical dimension that lent it much of its passion. Pocock and Skinner sometimes went beyond the historical thesis that intellectual history must be embedded in historical data to the assertion that there are no enduring political problems (e.g., sovereignty) and no transtemporal concepts. They seemed to imply that this could be established by induction, but obviously it cannot. It may be noted as well that the dichotomy, Historians vs. Philosophers, has no empirical reference, because neither group is epistemologically homogeneous. Transcultural problems and themes are the stock in trade of world historians, while historians such as Peter Munz have argued that historiography is an epistemological Bedlam. Another relevant point is that Strauss himself was schooled in neo-Kantian historical scholarship, a fact apparent in his early publications on Hobbes and Spinoza. His subsequent turn against “historicism” was a sort of treason against his class. Many of his students disparaged the historian's craft as antiphilosophy (which it is), and this raised historians' hackles. The rejoinder was that political philosophy is antihistory (which it is). In various essays Pocock has acknowledged the obvious point that philosophers and historians pursue distinct activities. Conflict arises when the historian's synoptic vision takes to wing, or when the philosopher begins making empirical claims about historical events. On that point, Pocock's irritation expresses the scorn of the professional for the amateur. But Pocock's heavy purchase upon the epistemology of Thomas Kuhn and others leaves him vulnerable to the criticism that he borrows illegitimately from philosophy. These historiographic debates bypassed a lucid exposition of the historian's craft, Hexter's, J. H.History Primer (New York: Basic Books, 1971). Hexter takes on philosophy and philosophers of history and shows how even the intellectual historian may and should avoid both.Google Scholar

3. H. R. Trevor-Roper stated that Hobbes was “outside the main stream of English political thought.” For Iring Fetscher, Hobbes “occupies a lonely position at the center [sic] of the Western philosophical tradition.” G. P. Gooch thought that “no man of his time occupied such a lonely position in the world of thought.”

4. Tönnies, Ferdinand, Studien zur Philosophie und Gesellschaftslehre im 17. Jahrhundert, ed. Jacoby, E. G. (Stuttgart: Frommann-Holzboog, 1975);Google ScholarMinz, Samuel I., The Hunting of Leviathan: Seventeenth-Century Reaction to the Materialism and Moral Philosophy of Thomas Hobbes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962);Google ScholarBowle, John, Hobbes and His Critics: A Study in Seventeenth Century Constitutionalism (London: Jonathan Cape,1951).Google Scholar

5. Caton, Hiram, The Politics of Progress: The Origins and Development of the Commercial Republic 1600–1835 (Gainesville: University Presses of Florida, 1988), pp. 187–202;Google ScholarReik, Miriam M., The Golden Lands of Thomas Hobbes (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1977), pp. 167f., 181;Google ScholarNicolson, Marjorie Hope, Pepys' Diary and the New Science (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1965), pp. 100–165.Google Scholar Norberto Bobbio includes an outstanding literature review of Hobbes studies since the mid-nineteenth century as an appendix to his Thomas Hobbes (n. 1 above).

6. Reik, , Golden Lands of Thomas Hobbes, pp. 174–88.Google Scholar On Hobbes's mathematics and his controversy with Wallis, see Jesseph, Doug, “Of Analytics and Indivisibles: Hobbes on the Methods of Modern Mathematics,” Revue d'histoire des sciences (in press);Google ScholarSchaffer, Simon, “Wallificarion: Thomas Hobbes on School Divinity and Experimental Pneumatics,” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 19 (1988): 275–98;CrossRefGoogle ScholarPycior, Helen, “Mathematics and Philosophy: Wallis, Hobbes, Barrow, and Berkeley,” Journal of the History of Ideas 48 (1987): 265–86;CrossRefGoogle ScholarSacksteder, William, “Hobbes: Geometrical Objects,” Philosophy of Science 48 (1981): 573–90;CrossRefGoogle ScholarShapin, Steven and Schaffer, Simon, Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985). I owe these references to Doug Jesseph.Google Scholar

7. The English translation was published in 1985 by the Fortress Press. The original version was Bibelautorität und Geist der Moderne: Die Bedeutung des Bibelverständness fur die geistesgeschichtliche und politische Entwicklung in England von der Reformation bis zur Aufklärung (Göttingen: Vanderhoeck und Ruprecht, 1980).Google Scholar Although Martinich runs a line similar to Eisenach's, EldonTwo Worlds of Liberalism: Religion and Politics in Hobbes, Locke, and Mill (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), this study is not referenced.Google Scholar

8. Reason, Ridicule, and Religion: The Age of Enlightenment in England 1660–1750 (London: Thames & Hudson, 1976), pp. 34, 70.Google Scholar Redwood's study is consistent with two earlier studies, Cragg, G. R., From Puritanism to the Age of Reason: A Study of Changes in Religious Thought within the Church of England, 1660 to 1700 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1950)Google Scholar and Jones, R. F., Ancients and Moderns: A Study of the Rise of the Scientific Movement in Seventeenth Century England, 2nd ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1961).Google Scholar

9. Aubrey, John, Aubrey's Brief Lives, ed. Dick, O. L. (London: Secker & Warburg, 1949), p. 165.Google Scholar

10. The classic modern study remains Jordan's, W. K.Development of Religious Toleration in England, 2 vols. (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1965).Google Scholar See also Caton, , Politics of Progress, pp. 120–39;Google ScholarAshley, Maurice, Finance and Commercial Policy under the Cromwell Protectorate (London: Cass, 1972), pp. 26–37;Google ScholarBouwsma, William J., Venice and the Defense of Republican Liberty (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968).Google Scholar

11. See Cranston, Maurice, John Locke (London: Longmans, 1957), p. 107f.,Google Scholar for a discussion. Martinich does observe that Hobbes, in denying that the pope is the anti-Christ, contradicts an article of the Westminster Confession (p. 320). Elsewhere (p. 333) he notes Hobbes's express submission to the dogmatic pronouncements of the Act of Supremacy, but does not test these pronouncements against Hobbes's theology as he interprets it.

12. Burnet, Gilbert, History of His Own Times (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1897), 1: 340–41.Google Scholar

13. These scandals are discussed by Caton, , Politics of Progress, pp. 203–219.Google Scholar On Newton's stable of young clergymen, see Manuel, Frank, Freedom from History and Other Untimely Essays (New York: New York University Press), pp. 162–83.Google Scholar

14. Among the religious who did not respond to Hobbes's call to “immortal peace” were the Quakers, whom he included in his sweeping imprecations upon the sedition of sects. That he did not recognize like-mindedness in the Quakers is another indication of his hostility to religion. Religious belief is incompatible with the will to construct a completely perspicuous doctrine of justice from “infallible reason.”

15. Bacon states that there have been only three periods of learning, each of 200 years duration: the Greek, the Roman, and in modern Europe (Great Instauratwn, Bk. I § 78). The Medieval—Renaissance periodization took its beginnings from Italian humanists who heralded a renewal of spirit after the long despotism of scholastic thought; see Ferguson, W. K., The Renaissance in Historical Thought: Five Centuries of Interpretation (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1948).Google Scholar Recent studies of Bacon, notably Whitney's, CharlesFrancis Bacon and Modernity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986)CrossRefGoogle Scholar do not discuss Bacon's historiography. Pérez-Ramos's, Antonio very learned Francis Bacon's Idea of Science and the Maker's Knowledge Tradition (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988) does mention it, but only in a footnote, where its similarity to Comte's Three Stage schema is noted.Google Scholar

16. The historiography dedicated to tracing the development of this partly philosophical, partly historical, partly sociological theory of progress is dispersed. Among Anglo-American historians, James Westfall Thompson's lifelong dedication to this task remains distinctive after five decades. See Medieval and Historiographical Essays in Honor of James Westfall Thompson, ed. by Cate, James Lea and Anderson, Eugene N. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1938).Google ScholarCaton, (Politics of Progress, p. 120, n. 17)Google Scholar incorporated Westfall's findings in his reconstruction of the prehistory of progress as Ghibelline politics. Trumpf's, G. W.Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought: From Antiquity to the Reformation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979)Google Scholar is the comprehensive study of periodization from antiquity to Paolo Sarpi. Wilcox's, Donald J.The Measure of Times Past: Pre-Newtonian Chronologies and the Rhetoric of Relative Time (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987) exhibits pathways out of the recurrence paradigm. The conventional literature on the idea of progress requires a comprehensive overhaul on the basis of these works.Google Scholar

17. Kraynak references Schochet, Gordon, “Thomas Hobbes on the Family and the State of Nature,” Political Science Quarterly 82 (1967): 427–45,CrossRefGoogle Scholar to support the ascription of primitive patriarchy to Hobbes's state of nature. Schochet himself notes that Leo Strauss had stressed this circumstance in his Hobbes study. I draw attention to Norberto Bobbio's outstanding discussion of the status of familial society in natural law theory prior to Hobbes (Thomas Hobbes, pp. 5–25).Google Scholar

18. I have been unable to obtain Isermann's book. For the bibliographic details of the Isermann and Prokhovnik books, see n. 1.

19. Prokhovnik, , Rhetoric and Philosophy in Hobbes's Leviathan, pp. 111–25.Google Scholar

20. Kraynak does not refer to Antonio Péiez-Ramos's historical study of this tradition; see n. 15 above.

21. J. W. Gough, an authority on the history of contractarian thinking, states that Hobbes's theory comes “straight out of Glaucon's speech.” See his The Social Contract: A Critical Study of Its Development, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1957), p. 103.Google Scholar

22. Tertullian, , Ad Nationes II. i–xvii;Google ScholarLactantius, , Div. Inst. II. 3;Google Scholar III. 5. 20; Arnobius, , Adversus Nationes iv. 29;Google ScholarAugustine, , City of God, vii. 18.Google Scholar This scandal was discussed at length by Cicero in numerous writings, e.g., De Natura Deorum I. xlii. 118–21.Google Scholar

23. Cicero, , De Finibus V. ix. 24ff.Google Scholar

24. Gough, , Social Contract, p. 49. Gough states that “a contractural principle … was implicit in the political system of Carolingian times, and explicit references to an actual contract occurs from [the ninth century].” The struggle between popes and emperors was the stimulus to this thinking.Google Scholar

25 Cicero, , Republic III. xi–xiii.Google Scholar This text, with its obvious reference to Glaucon's speech in the Republic, was discussed by numerous Christian writers, e.g., Lactantius, , Div. Inst. v. 17–18,Google Scholar who attributes it to Carneades and who says that Cicero did not know how to refute it. The medievals did not wish to refute it since the biblical tradition, particularly as mediated by Augustine, viewed political power as the construction of violent men. Thus the concept of the social contract, inclusive of an antecedent lawless state of nature, was an established point of view among medieval canonists and legists. See Gierke, Otto, Political Theories of the Middle Age (Boston: Beacon Press, 1958), pp. 87–93.Google Scholar Gierke credits Aeneas Sylvius's De Ortu with a particularly clear exposition of this concept. Bobbio's discussion of the history of natural law and social contract traditions is outstanding, although he does not recognize the pope-emperor struggle within which it was framed, nor does he refer to the literature on it. See Monahan, Arthur P, Consent, Coercion and Limit: The Medieval Origins of Parliamentary Democracy (Kingston: McGill University Press, 1987);Google ScholarOakley, Francis, Natural Law, Conciliarism and Consent in the Middle Ages (London: Variorum, 1984);Google ScholarUllmann, Walter, The Growth of Papal Government, Law and Politics in the Middle Ages: An Introduction to the Sources of Medieval Political Ideas (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1975);Google ScholarTierney, Brian, The Crisis of Church and State 1050–1300 (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1964).Google Scholar

26. Sommerville's solid discussion of Hobbes's sovereignty doctrine (pp. 80–89) reminds us that Hobbes admitted that he held the same view as Bishop Manwaring. Sommerville does not mention the patristic tradition nor parliamentary acts that declared the sovereign to be absolute.

27. Brown, Peter, Augustine of Hippo: A Biography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967);Google ScholarDeane, Herbert A., The Political and Social Ideas of St. Augustine (New York: Columbia University Press, 1963), pp. 46–53, 120ff.Google Scholar

28. Tertullian, , De Carne Christi, chap. 9;Google Scholar see also his De Anima, chap. 7. Classical materialism underwent an important medieval development that informed the study of mechanics and sense perception. A probable common source for Bacon, Descartes, and Hobbes is the Spanish priest Donius's, De Natura Hominis (1581), which sets forth (Bk II, 16–21) the doctrine that omnes operationes spiritus esse motum et sensum. A more or less complete materialism follows from this.Google Scholar

29. Caton, , Politics of Progress, pp. 19–32, 87–110,187–202,321–30,357–31, 459–69.Google Scholar