Introduction

In January 2019, US president Donald Trump tweeted an image, combined with a political slogan, which generated 242,000 likes and 71,000 retweets.Footnote 1 In the image, Trump poses as the builder of the ‘Wall’ and appears against a dark purple background as a larger-than-life figure. In the front bottom is a vast landscape cut horizontally by a steel fence, vaguely showing a landscape or settlement on the far horizon. Trump is portrayed with a dignified, earnest demeanour, god-like and looming above the semi-transparent steel fence in a desert-like area. The accompanying text reads ‘The Wall is Coming’. The text obviously references the well-known HBO show Game of Thrones, which popularised the slogan ‘Winter is Coming’ and simultaneously featured a wall as central role to the plot. Ironically, that wall proves incapable of providing protection against the evil forces of the Night King and his army of the Undead. It becomes the battleground for different groups’ brutal fights that, in fact, are never fully deterred or hindered by the wall. In combination, the image and text transform Trump's fantasy of building a wall – resulting in the government shutdown of early 2019, the longest in US history – into an epic struggle against a greater evil that is both extremely threatening and diffuse. The iconic image and warlike message underline Trump's strength (political and otherwise) and promise the fulfilment of one of his central election promises, namely building a wall on the US-Mexican border.

As an instance of political storytelling, the tweeted image is significant. It features no boring political manifesto. Instead, it is a highly entertaining and somewhat fantastic rendering of politics as an epic battle. While such images may have high symbolic value thanks to their immediate accessibility to a broad audience, they are easily forgotten soon thereafter. At the same time, images are generally omnipresent and thus make for important elements in the political storytelling that shapes political discourse over time. Often in combination with text, images uniquely condense information, convey stories, and give easy access to broader political contexts. This allows for a vast array of responses and thus appeal to a great spectrum of observers.Footnote 2 Since we are interested in the routines and technologies of international politics that stabilise or destabilise certain ideas and practices, we will not focus on images that depict grand moments such as G7 summits, the Donald Trump and Kim Jong-Un meeting, or extreme crisis events that become ‘iconic images’.Footnote 3 Instead, we concentrate on everyday political representations.

Taking the appeal of images as a starting point, our article aims to explore them in their larger political context to show how images function as attempts at interpretive closure by conveying what is politically (im)possible in terms of policy options. ‘Appeal’ in our interpretive reading refers to the performative dimension of presentation rather than reception, to which we have no analytical access. Thus, when we talk about the appeal of a narrative or symbolic representation, we refer to the potential for pleasure they may incite among recipients, drawing on different affectual registers like indignation, outrage, schadenfreude, etc.Footnote 4 Appealing to fantasy, such images, embedded in narratives, allow for a variety of responses while being simultaneously geared towards implicit consent. While policy programmes or speeches are often seen as detached and elite-driven, images are vital elements of political storytelling whose universality allow them to address issues in a manner that is distinct to official statements. As routine narrative devices, they may exert power particularly because they appear inconspicuous and apolitical.Footnote 5

IR scholars have recently put more emphasis on the importance of narrativesFootnote 6 and visualityFootnote 7 to better understand the cultural foundations of international politics. However, not many have attempted to connect these different strands in conceptual and methodological terms.Footnote 8 Assuming a productive relationship between images and other forms of representation like text, we propose to study them with the technique of layering.Footnote 9 Starting from the image and its performative nature, we turn to the accompanying text in a second step, and, in a third, the contextualisation within political narratives. As a fourth layer, we focus on the polyphonous dimension, which refers to alternative or competing narratives, thereby pointing to a larger societal discourse. This fourth interpretive step is informed by narratology, which is interested in different narrative orientations and emphasises (similar to discourse studies) that it is by no means an ‘innocuous question’ to ask what narrative ‘is able to prevail in a given interpretive marketplace’.Footnote 10 A general tenet of interpretive research is that there is a mutual entanglement between the empirical analysis and the methodological and theoretical concepts. This is why we do not separate strictly between our theoretical and methodological perspectives, but have developed them in close resonance with our interpretive work.Footnote 11 As a contribution to these bridging attempts, we propose combining conceptual elements and methodological tools in a form of analysis we describe as ‘visual narrative analysis’.Footnote 12

The goal of this contribution is to account for the interplay between different layers and their performative effects as is similarly done in discourse and metaphor analysis involving notions of intertextuality and webs of meaning.Footnote 13 Our own familiarity with the European context of political storytelling from daily encounters with the traditional media, social media, and other communications as well as our frustration with the normalisation of populist storytelling have led us to study right-wing populist storytelling here.Footnote 14 The choice of subject in terms of empirical material reflects our intent to demonstrate the applicability of our approach, that is, identify a genre of political storytelling among others that routinely links images and text. Populist storytelling ostensibly relies on its appeal to fantasy (which at least gradually distinguishes it from political narratives of more established parties) and even scandal. At the same time, we are not interested in the highly debated images used by populist parties, since the potential appeal of storytelling in election campaign posters cannot be reduced to scandal. More broadly speaking, visual narrative analysis can be applied to very different instances of image/text combinations. Therefore, we focus here on rather inconspicuous, seemingly harmless representations, taken from a broader sample of election campaign posters, since they offer potential for a layered analysis.Footnote 15

Even though IR has hitherto paid relatively little attention to populism, overlaps with issues such as migration, gender, ambiguities of liberalism, or Brexit have been acknowledged as relevant by many (often critical) IR scholars.Footnote 16 Against the background of the Brexit referendum and the election of Trump, the rise of populists has been commented upon through the prism of the blurring line between fact and fiction, and their contempt for groups such as migrants, women, and sexual minorities. Thus, we start our visual narrative analysis within this field of pressing political interest.Footnote 17 We take a look at some of the ways in which right-wing populist parties attempt to mobilise support and gain voters through visual storytelling.Footnote 18 Although there are other kinds of political storytelling, we will mainly focus on populist parties as its most prominent practitioners, fully aware of the blurred boundaries between these groups and other more established parties.Footnote 19

The analysis is first a conceptual contribution to broader debates within sociologically informed International Relations on the role of cultural underpinnings in international politics. Ranging from constructivism to poststructuralism, the construction of collective identities of political communities is explained through shared/divided narratives and practices of storytelling.Footnote 20 Secondly, the methodological implications of a visual narrative analysis contribute to debates on how to study visual representations of politics and the productive relationship between images and text in the broad spectrum of political storytelling.Footnote 21 Thirdly, our analysis of the particular examples reveals that such narratives (re)produce gender stereotypes and societal hierarchies.Footnote 22 These powerful social constructs offer identification, the potential for differentiation, and may therefore generate support for populists. The findings resonate with recent analyses in IR gender studies.Footnote 23 Most generally, we aim to make a case for visual narrative analysis to contribute to a better conceptual understanding of political storytelling and the performative dimension of its potential appeal to public audiences. In two short case studies we illustrate the promises of a visual narrative analysis.

The puzzling appeal of narratives

Narrative approaches are currently experiencing a renaissance in studies of politics and the political. The concept of narrative is an interdisciplinary term in the tradition of literary studies, narratology, and cultural studies.Footnote 24 While the term is sometimes narrowly used in terms of strategic action, we suggest a processual and relational notion of narrative as it is established in much practice-oriented and discourse-oriented research in IR.Footnote 25 As shown in recent research approaches in IR, the concept is analytically promising when studying political phenomena as varied as the construction of European identity,Footnote 26 the collective sense-making of political crisis moments like September 11,Footnote 27 transitional justice processes,Footnote 28 civil society myths in global governance,Footnote 29 the legitimation of targeted killing in the war on terror,Footnote 30 or the construction of the boundaries of Europe.Footnote 31

Sense-making, plotting, and the fantasmatic logic

Narratives are a form of configuration device by which actors seek to make sense of the world and order it in a specific way. As Jerome Bruner famously remarked, ‘we organize our experiences and our memory of human happenings mainly in the form of narrative – stories, excuses, myths, reasons for doing and not doing, and so on’.Footnote 32 Narrative approaches therefore assume that ‘human beings are inherently storytellers who have a natural capacity to recognize the coherence and fidelity of stories they tell and experience’.Footnote 33 While a strict separation between ‘the real’ from ‘the fictional’ or the myth from the logos has been pervasive both in everyday as well as academic understandings, narratalogy challenges such clear boundaries. Our day-to-day language renders it obvious that the boundaries are blurred. It is not a coincidence that the evaluation of current political events (for example, the Brexit vote, Donald Trump's electoral victory, Erdoğan's rise) is often made tangible through the prism of literature (for example, Shakespearean drama), Netflix series (for example, House of Cards), and films (for example, The Great Dictator); or that politicians, in turn, seem to take cues from fictional representations to orchestrate their performances (for example, Macron posing in Versailles). Narrative approaches move social science research closer to the research agenda of cultural and literary studies by reconsidering the creative and strategic capacities in storytelling activities of all kinds.Footnote 34

Narrative constructions of the world are therefore attempts at making sense of reality. Storytelling is subjective and linked to practical judgements of selective interpretation, personal experiences, and sequencing of events.Footnote 35 Narratives require some sequential ordering of events, but the events themselves need not be real.Footnote 36 As Barbara Czarniawska argues, when narrative is the ‘main device for making sense of social action’,Footnote 37 it is also a political device that generates legitimacy and mutual agreements. It can be argued that the ‘successful legitimation of a political project relies on the narrative that is attached to it’.Footnote 38 However, the efficacy of narrative depends on established sociocultural narrative conventions as a ‘stock of stories’ and therefore works dialogically.Footnote 39 Searching for a common understanding through narrative is a fragile process of retelling stories and depends on cultural repertoires of distinct communities,Footnote 40 including iconic images or common stories that do not necessarily resonate with other communities, for instance national security narratives.Footnote 41 Narratives are organised in particular configurations, or ‘plots’ that ‘weave together a complex of events to make a single story’.Footnote 42 The dimension of power is crucial when a narrative is configured and sequenced in a beginning, middle, and an end, that is, emplotment.Footnote 43 To argue that narratives are always part of power relations does not imply that this refers to the material capacities of the storyteller. Rather, storytelling is embedded in cultural practices of communication and related to distinct opportunities of articulation. For instance, certain taboos – which could refer to historical precedents of belligerency – delimit narrative options, but can also be broken strategically. Recent articulations by far-right German politicians who relativised The Holocaust as historically insignificant, or praise for colonial times by UK politicians, followed by rather half-hearted public apologies, can be seen as strategic attempts at infringing upon particular taboos.Footnote 44 More contingently, discourses open/close to respond to societal changes, such as discriminatory speech or cultural appropriation. The choice of plots is not endless, however. The classic plot genres in the tradition of Hayden White such as romance and tragedy work not only in literature and films; they also shape our practices of political storytelling.Footnote 45 The negotiation of identity in political issues, such as postconflict situations, is mainly a negotiation of literary plots, as Nadim Khoury has shown.Footnote 46

How narratives are configured and how knowledge is selectively appropriated is primarily an issue of claims to power and authority. Selecting the beginning of a story, for instance in processes of transitional justice, is already an intrinsically power-imbued action because it determines which information disappears, and which events are kept alive.Footnote 47 Once a plot has been established, the association of events with actors is likely, also described as characterisation.Footnote 48 Such transformations of actors into characters imply moral judgements. It makes a difference for policy options, for example, whether migrants are described as human beings seeking protection or as potential criminals. As it is rather difficult to define criteria for ‘successful’ political storytelling, policy analysts have reconstructed often-used storylines in policy controversies.Footnote 49 Hendrik Wagenaar draws on narratology to show how political stories become appealing: they are open-ended and deal with possibilities not certainties; they are subjective and involve concrete people (as characters); they are value-laden and function through moral positioning; and they are action-oriented by providing suggestions and a certain measure of provisional certainty that allows persons to act at all.Footnote 50

Political storytelling has its own logic, but is not completely detached from the larger cultural repository of familiar stories. As noted above, not all stories are equally successful – in the sense of their reception – which can be explained in part by their fit with known narratives, which contributes to their general potential for resonance. This resonance, which means the potential success, of storytelling is conditioned on the way in which people can relate to stories, but remains contingent. The idea of ‘fantasmatic logic’Footnote 51 helps us to contextualise how resonance can be created by ‘appeal’. The fantasmatic logic is instrumental in trying ‘to maintain existing social structures by pre-emptively absorbing dislocations, preventing them from becoming [politicised and transformed]’.Footnote 52 Assuming a general desire for countering the lack (of fulfilment) individuals experience in their life, fantasy bridges inconsistencies and thus prevents issues from becoming part of the domain of the political, where these meanings, articulations, and identities are instituted and challenged through hegemonic struggles, contestations, resistance, and dislocations. This is important, since grand narratives of today's politics function only because of constant attempts at removing them from the everyday business of political squabbling, and thus make them less likely to be challenged. For the analysis of social phenomena, identifying political logics helps to demonstrate how social practices are constituted and transformed, whereas fantasmatic logics reveal why certain political projects are supported whereas others are not.Footnote 53

The introduction of fantasmatic logics does not assume a neat distinction between the dimensions, but pays closer attention to the subjects addressed by storytelling. The removal of problems and issues from the political arena to the realm of the fantasmatic renders these underlying issues invisible and alters their perception, for instance by making lies (or ‘alternative facts’) irrelevant as long as strong emotions can override them. More precisely, issues presented in the fantasmatic logic can evoke pleasure in their recipients – both through positive messages (for example, ‘Empire’, see below) and negative ones (for example, agreeing that the imprisonment of migrant children is horrible). As political visions, this can mean ‘the beatific dimension of fantasy – or which foretells of disaster if the obstacle proves insurmountable, which might be termed the horrific dimension of fantasy’.Footnote 54 The rejection of elites or the ridicule towards ‘political correctness’ can thus generate responses that replace concerns for affordability or feasibility, which would classically be addressed in the political realm. As a consequence, (political) contestation is difficult because the object of contestation is seemingly apolitical and cannot be addressed on the same plane as a more concrete political promise of, for instance, higher wages or tax cuts. Politics, as practices that involve planning and implementing programmes, rarely follow the logic of the political alone, which is why the idea of fantasmatic logic is an interesting addition to understanding how political storytelling can be rendered appealing.

For instance, the recent re-election of Narendra Modi as Indian prime minister despite his failure to implement his promises for economic growth has largely been attributed to his clear Hindu-nationalist and anti-Muslim stance, which apparently also mobilised enormous numbers of voters who had been harmed by his policies.Footnote 55 Appealing to a fantasy of purity and unity (in a heterogeneous state like India), Modi's election campaign narratives resonated with the public so well that election results of 2019 trumped those of 2014, which surprised all political observers, including his own party. The example of Trump's ‘Make America Great Again’ slogan or the UK's UKIP story of a return to British Empire-era greatness similarly have little connection to everyday policies and politics, but instead propose visions that have clearly appealed to political audiences. Both evoke feelings of pride or desires for a better life and are attempts at depoliticisation. One of the main uses of fantasy in emplotment is in providing points of identification. ‘When successfully installed, a fantasmatic narrative hooks the subject – via the enjoyment it procures – to a given practice or order, or a promised future practice or order, thus conferring identity’.Footnote 56

In that regard, stories can function as ‘affective triggers insofar as emotions and narrative are deeply intertwined’.Footnote 57 At the same time, the intertwinement between narrative and emotion also goes the other way, as the meaning of emotion is hard to disentangle from narrative emplotment.Footnote 58 As Roland Bleiker and Emma Hutchison argue, ‘emotions help us make sense of ourselves, and situate us in relation to others and the world that surrounds us’.Footnote 59 ‘They frame forms of personal and social understanding, and are thus inclinations that lead individuals to locate their identity within a wider collective.’Footnote 60 They can create a certain kind of ‘collective attachment’Footnote 61 decades after the end of the Second World War, the history of victory and defeat still shapes European relations and the political storytelling of the European Union. The narratives used to unite people under a common affective storyline that both conveys emotional content and offers emotional orientation create identities around content and emotions alike, oscillating between political and fantasmatic logics.

Fantasmatic logic, in particular, can provide a supplement to the understanding of politics as solely oriented towards specific goals:Footnote 62 ‘[m]oreover, such logics typically rely upon narratives which possess features distributed between public-official and unofficial forums. This is because fantasies seek directly to conjure up – or at least presuppose – an impossible union between incompatible elements. … In addition, we could say that aspects of social reality having to do with fantasmatically structured enjoyment often possess contradictory features, exhibiting a kind of extreme oscillation between incompatible positions.’Footnote 63 Finally, as Bleiker and Hutchison further argue, the influence that representations of emotion exert on political dynamics is particularly evident in the realm of visual culture.Footnote 64 While in IR, images of extreme crisis events such as September 11 or the torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib are used to demonstrate the politics of emotion,Footnote 65 we focus on images in populist election campaigning to highlight the linkage between narratives and images with regard to their appeal. In the following chapter, we will show how to integrate visual analysis into narrative analysis.

Layered interpretations: Embedding visual representations in narrative analysis

Narratives can take shortcuts to recipients without addressing issues in their full complexity, particularly in their use of imagery and metaphorical language. Therefore, a visual narrative approach needs to consider both the object of study, that is, images and text, and the explicit as well as implicit linkages to a larger political story. As earlier studies have shown, metaphors and, indeed, images, in addition to roles and plots, serve as constitutive elements of narratives that can be analysed in their complementarity and offer focal points for analysis.Footnote 66 Images do not play a passive role, therefore, but can be understood as an ‘iconic act’ – similar to speech act theory – that underlines the performative dimensions of showing and seeing.Footnote 67 As elements that become (analytical) entry points to narratives, metaphors and images allow for the reconstruction of narratives in the same way that they function in political narratives to structure collective sense-making; they may over time become so accepted that they are not considered metaphorical at all by the audiences.Footnote 68

Images and metaphors are key points that interweave storylines, exemplify certain plots, and are established means of transporting emotions. They are, first of all, indicators of different narratives, and therefore the first available object for interpretation. Furthermore, they need to be contextualised, and researchers need to see how they are configured within the narrative, connected to moral judgements, and related to distinct characterisation of political actors. For Deborah Stone, metaphors are pervasive in policy language, ranging from organisms and machines to war and disease.Footnote 69 Offering a semantically (and visually) open frame of reference, metaphors/images are characterised by descriptive and prescriptive power.Footnote 70 By highlighting some aspects and obscuring others, they organise perceptions of reality and suggest appropriate actions in light of those perceptions.Footnote 71 Metaphors, accordingly, go beyond description, as they develop prescriptive power in influencing the imagination of actors and audiences and thus suggest (or delimit) options for political action. ‘Metaphor is not a harmless exercise in naming’, as George Lakoff and Mark Johnson claim, since ‘it is one of the principal means by which we understand our experience and reason on the basis of that understanding. To the extent that we act on our reasoning, metaphor plays a role in the creation of reality.’Footnote 72 Effectively, their dependence on cultural and societal references as well as cultural knowledge can lead to differing understandings and uses by diverse groups. Under conditions of polyphony of narratives this openness creates opportunity for political struggles and new constructions of reality through redescription. Thus, metaphors are neither true nor false.Footnote 73 Hence, narrative analysis's growing relevance in interpretive analysis is also ‘rooted in its ability to serve as a tool for describing events and developments without presuming to voice a historical truth’.Footnote 74 As Paulo Ravecca and Elizabeth Dauphinee argue, narrative scholarship ‘puts the multilayeredness of life back into science’ and acknowledges contradiction and ambiguity as key features of our sociopolitical lives.Footnote 75

Doing visual narrative analysis

Similar to metaphors, images – including videos, memes, or similar pictorial items – are another shortcut to identifying narratives, since they incorporate different layers of information, ranging from the obvious surface of what is depicted to allusions and intertextual references that create (and possibly limit) horizons of interpretation, the interrelation between ‘being, knowing and becoming’.Footnote 76 Images that also include written text, such as the election campaign posters we are all familiar with, combine imagery with clear textual messages, often with allusions to political narratives in both genres.

Our analysis is oriented towards the methodological suggestion by Axel Heck and Gabi SchlagFootnote 77 to use the iconological approach in the tradition of Erwin PanofskyFootnote 78 for analysing images.Footnote 79 This enables us ‘to see how images symbolically perform how we see what we see’ (by taking their social embeddedness into account).Footnote 80 Similarly, our technique can be understood as layered interpretation, that is, as a combination between iconological and narratological approaches. A reconstruction of narratives that starts by contextualising metaphors and images can add layer upon layer of interpretation, since symbolism used in text and images can mean different things in different contexts. We make a further interpretive move towards understanding the underlying presuppositions of the images and their performative dimension by pointing to the interpretive closure that narratives may produce for future political action.

In a first step, we describe and analyse the image; composition, atmosphere, symbolism, etc. can be studied in isolation from all other contextual information. Furthermore, we consider the cultural allusions of images, providing intertextual context of the visual presentation. In a second step, the textual comment will be added. We reconstruct how image and text are positioned towards each other, for example, whether they are complementary or juxtaposed, and analyse how they create and delimit opportunities for certain interpretations and affective responses. This goes beyond visual analysis, since the narrative content of an image can be very different from its textual supplement; for instance, an image can draw upon certain kinds of cultural repertoires, like well-known art historical topoi, while the text draws upon others. In a third step, we will add the narrative context, in terms of plots, roles, and relations. Here, different images can be related to each other, to show how a political narrative is created around metaphors and images. We refer back to recent research on populism in order to see how our findings resonate with their insights. Identifying larger, polyphonic structures adds a fourth layer, which most explicitly demonstrates the importance of narrative studies in the social sciences.

Two narratives of masculinity, nation, and motherhood

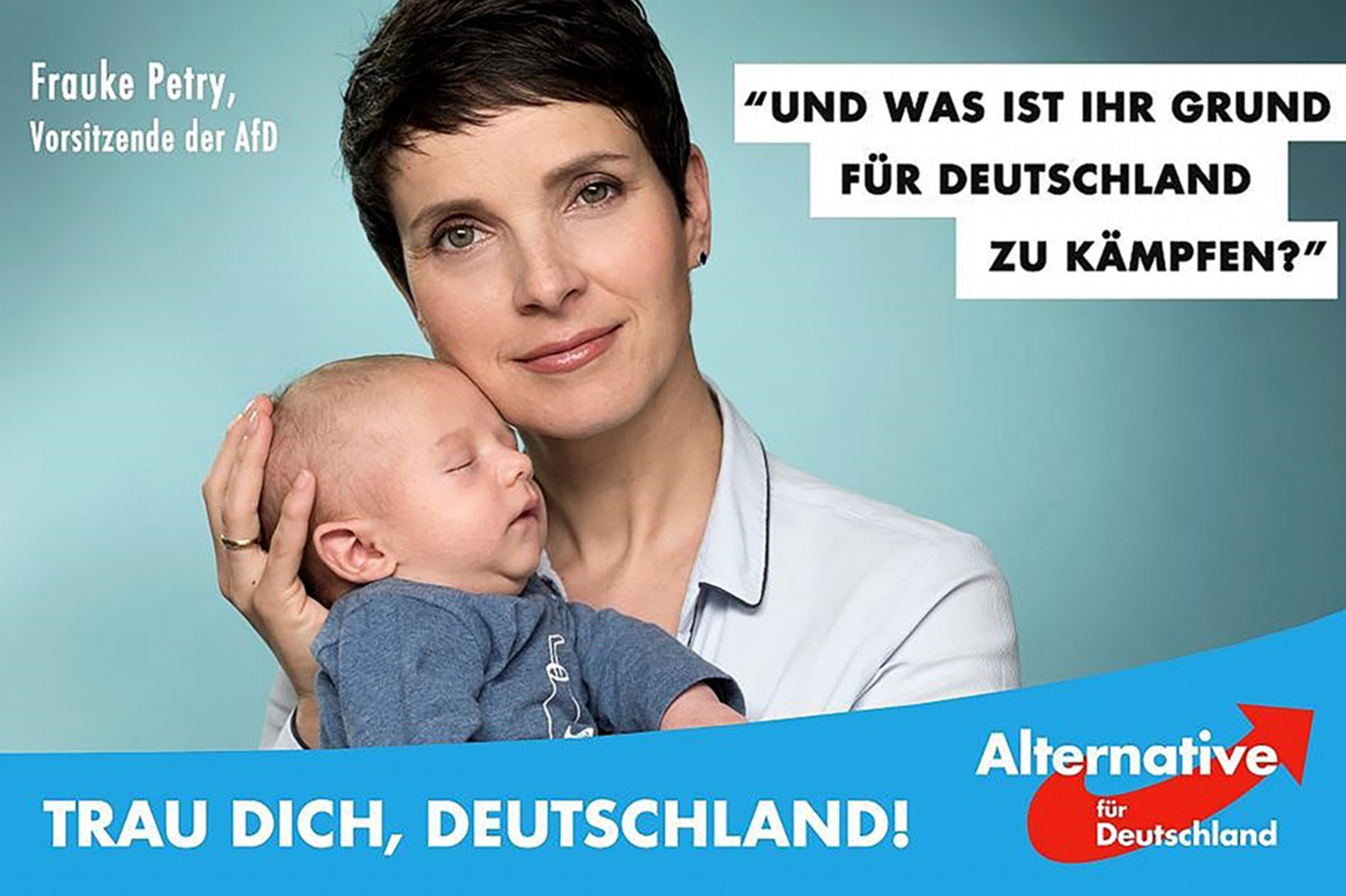

The following section presents our interpretation of visual narratives in right-wing populist election campaigns. Election campaign posters represent a central type of images-text combinations that follow certain conventions, have an extremely high reach, and meet (in contrast to social media) every citizen in their everyday life, which is why they remain such elemental media for political parties with which to relate to the demos.Footnote 81 Systematically going through election campaign posters issued by right-wing populist parties in Europe, we came to select a small sample that we use to illustrate our conceptual and methodological points. With the goal in mind to analyse only material from right-wing populist parties in established European liberal democracies, we studied campaign posters in five different countries of the last two respective parliamentary elections. Hierarchical societal relations and the centrality of gendered politics were one of the main topoi we came across in the study of election campaign posters overall, which is why decided to further pursue them.Footnote 82 From the wealth of posters, which gave us a broad overview of the main topics addressed, we further selected two that – as described above – offer the challenge of being less striking (and thus less aimed at provocation) than others, while taking up the gender issue we identified as central. Therefore, these two posters help us to demonstrate what a layered interpretation brings to the fore, without already exhausting all interpretations at a glance. One image shows a British fisherman named Tony, while many others in our larger sample show (predominantly white) girls and women, or at least parts of them (for example, pregnant torsos). The main exception in our sample is the image of a well-known female (German) politician, Frauke Petry, with a child, which, however, is closely interlinked with depictions of many other, unknown women.

While our storytelling partly reflects our own responses to the images and text,Footnote 83 as interpreters of the visual material, we also try to explore the appeal of visual narratives through the performativity of image/text relations in more general terms and present the results as plausibly as possible through our layered interpretation technique. Selecting and interpreting the material, and going through the material until we found our interpretation saturated, we identified two narratives that characterise the material in terms of messages, modes, and content, which are inherently interlinked with each other. Since our primary aim is to illustrate exemplarily but in depth what a layered interpretive analysis reveals, we have not used a more inclusive sample. We name the two narratives (1) Honest Men Under Threat and (2) Proud Mothers.

Honest Men Under Threat

A key populist narrative is the imagination of a ‘true body’ of the people that is under threat by external (evil) forces such as the EU, the capitalist system, or migrants, and that needs to be protected by the ‘true people’, who are ignored by their corrupt political elites. During the so-called refugee crisis in 2015, in many European countries, metaphors of neverending streams of migrants became dominant, which evoked feelings of powerlessness, excessive demand, and loss of control. The voice of the migrants, who seek protection, disappeared in political discourses. Thus, the ‘crisis’ was perceived as a technical problem or even a natural catastrophe, which needed to be solved or contained. Many right-wing populists used this discursive shift to legitimise a stronger isolationist policy against immigration. The UKIP campaign is a particular case as the political movement was eventually successful in pushing the populist narrative around the combination of the EU and migrants as enemy images, which mobilised collective emotions of insecurity and heteronomy.

On one of the most controversially discussed UKIP campaign posters we find the image of a human chain of migrants, whose end disappears in the blurry horizon and therefore supports the metaphor of a neverending stream. The main slogan ‘Breaking Point’ deals with the feeling of powerlessness to support the claim of an overstretching limit, and the additional slogan ‘The EU Has Failed Us All’ provides the moral judgement for the responsibility of the crisis. The visualisation operates with an objectification as single individuals and suffering people are not recognisable.Footnote 84 The visualised faceless mass suppresses feelings of empathy and supports the populist narrative of ‘Take Back Control of Our Country’. While this campaign poster example transports its clearly racist message also through a combination of image and text and mobilises collective emotions in distinct communities between fear and disgust, there is no need of a deeper analysis. A more interesting case in the same context of the imagination of the ‘true body of the people’ with regard to the suggestion of visual narrative analysis is the figure of fisherman Tony. Here, the populist message and the desired emotional mobilisation are more ambivalent.

Fisherman Tony as cipher for the ‘forgotten white men’

Tony Rutherford became one of the famous figures of the UKIP campaign, as he symbolised a typical British fisherman and used his popularity to give patriotic statements around EU fishing quotas in public debate.Footnote 85 On the campaign poster, this elderly fisherman is shown in his work gear, wearing a red plaid shirt underneath yellow overalls. He sports the typical black cap of a fisherman and is positioned in front of several small boats in a little harbour, carrying a rope in his right hand and a fish he apparently caught in the left. The visual configuration puts Tony, who is positioned on the left front side of the image, in the focus of the viewer, mainly because of the sharp contrast between the colourful figure of Tony and the grey, cloudy background. Tony looks serious and resigned, like a man who has lost his hope for a better future and knows that he needs to continue his hard labour until the end of his life. The harbour environment also precludes feelings of optimism, as it looks grey, deserted, and bleak. No other person is seen to be working there. The image may evoke sympathy for Tony,Footnote 86 who works hard but seems to be alone and forgotten, much like the steel workers in America's rust belt.Footnote 87

The slogan reads: ‘Gutted. Tony's business has been ripped apart by the EU.’ While ‘Gutted’ at a first glance and mainly addresses Tony's disappointment with the EU, the pun on literally ‘gutting’ fish creates a close linkage to the image, adding a further textual layer. Tony therefore appears as a stereotype of the hard-working patriot who has been betrayed by the elites of the EU, as the slogan ‘Gutted’ suggests. The EU is clearly characterised in the role of a technocratic destroyer of the traditional, but good life by the claim that ‘Tony's business has been ripped apart by the EU’. The dramatisation of crisis, breakdown, or threat is a repetitive plot pattern in populism.Footnote 88 Similarly, UKIP presents itself as the ‘only one party [that] will stand up for you’, according to the slogan. The populist narrative suggests that people like Tony have a clear option to come out of their hopeless situation by voting for a party that has not forgotten them. The fact that they know the fisherman by name reinforces the idea that UKIP is deeply interested in him and others like him. The Union Jack logo, in combination with the slogan ‘Believe in Britain’ provides an emotionalised storyline of patriotism and ways for ameliorating the dramatic condition of suffering workingmen. There are ways of overcoming feelings of humiliation, the message implies. The plot of betrayal points to the moral break that causes the governed to lose trust in the government. Thus, the government has lost its legitimacy to act in the name of the people, as they no longer serve their interests.

In another image of the UKIP campaign, the top candidates of the other parties (David Cameron, etc.) are gagged by a blue ribbon in the colours of the EU and the symbolic stars. They have lost their voice, the UKIP slogan indicates. The people cannot trust them anymore, because they are the mute puppets of EU bureaucrats. The only man that is not gagged, and thus able to speak freely, is Nigel Farage. He is therefore the only option to change the condition of voicelessness, and to fight for people like Tony, whose trust in the government has been lost. The narrative plays with the typically constructed populist antagonism between an external, corrupt system of political actors who have lost all touch with society and act in a bubble of profit and nepotism, and the ‘true people’ or ‘honest men’.Footnote 89 The underlying insinuation is that the elites in government are simply not interested in the needs and concerns of ordinary people. These people, however, represent the lost, but true patriotic spirit of the ‘body of the people’, who deserve more respect from politicians.Footnote 90

It is no coincidence that the figure of Tony, UKIP, and the EU are all represented by male figures. The threat of emasculation, implied in Tony's defeated stance and the gagging of British politicians, equates to the loss of control that a UK within the EU faces. Only by reclaiming control can men return to their perceived traditional role and regain their masculinity. A profession like fishing, which is predominantly male and working class, symbolises good, simple masculine life that is portrayed as unpolluted by postmodern lifestyles. Thus, the EU, similarly perhaps to the constraints of modern life (with its political correctness, technologies, and gender equality), embodies a fundamental threat – ‘gutted’ means killed and massacred – to a good life for men. The underlying fear of men like Tony of becoming irrelevant in this modern world is perfectly captured in the antagonism between the simple fisherman and the remote, uncaring and technocratic EU.

Ghost of the heartland

With a broader view, the example of Tony shows that the combination of image and text creates more complex narratives around collective emotions. What makes the example of fisherman Tony interesting from the viewpoint of visual narrative analysis is that it summons an image of a better, bygone world from the country's past. Fishermen have done their jobs for centuries or even millennia and are thus metaphors of the true Britain that existed long before the advent of the EU. Famous paintings of fishermen at sea who struggle against the forces of nature (for example by William Turner) come to mind.Footnote 91 Thus, Tony's world seems to be more real and honest than the busy life of bankers in remote, elitist London.Footnote 92

Paul Taggart used the term heartland to explain that the category of ‘the people’ remains abstract, whereas the imagination of a backward-looking utopia in the past mobilises collective fantasies of a better world.Footnote 93 The heartland metaphor evokes imaginations of a romanticised, ahistorical, and ideal world such as ‘Middle America’, or ‘La France Profonde’. Political narratives relate these imaginations via roles depicted by the likes of Tony the fisherman, or the steel workers in the rust belt in Trump's campaign, and thus create the desire for a purer life and world, in which the complex problems of our time are not present. This contradiction to the EU's support of structural change of formerly industrial regions is neglected and depoliticised by use of the fantasmatic logic. The existing problem of economic transformation in the industrial sector in many Western countries is reframed as a romantic myth of an ideal heartland as a place of harmony and wealth. Yet, the narrative construction around ideas of inward-looking (national) organic communities denies pluralism as it provides justifications ‘for the exclusion of the demonized’.Footnote 94 Such a narrative is mainly directed at men who are believed to suffer disproportionately from these economic transformations and struggle with the challenges of globalisation. The promise of a heartland through visual storytelling is a means for identification and appeal to honest, patriotic working people, and creates the misleading imaginary ideal of an easy political solution for them.

The UKIP campaign is a prime example of how right-wing populists draw on this heartland narrative in the distinct cultural context of the formerly glorious British Empire and how this leads to a further competition between political narratives over the authority to dominate the polyphonic discourse. This is the fourth step of layering and leads us to the political controversy around and after the Brexit referendum. In the desperate search by former prime minister Theresa May for a pragmatic solution to the Brexit decision, the different groups of political actors lead the debate to a radicalised antagonism between the two options of leaving the EU (‘hard Brexit’) or remaining in the EU through a new referendum. The ghost of the heartland narrative produces a toxic mixture for the culture of debating and leaves no space anymore for compromise. It is further pushed by conservative hardliners like Jacob Rees-Mogg and UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who create different stories around the plot of betrayal against the people, which gains moral weight by claiming a quest for truth, emancipatory action, and a call for justice in the face of deceit. Johnson, for instance, recently reactivated the Honest Men Under Threat narrative by the fictional claim that the EU ruins British fishermen on the (non-EU) Isle of Man through rules to keep fish fresh in a plastic ice pillow (in fact a regulation issued by the UK government). He even held a fish in his hands (like Tony in the poster) during a speech to complain about ‘pointless’ kipper rules and to show solidarity with the British fishermen.Footnote 95 The fantasy of this betrayal of honest men in a true Britain has been narrated in different variations, including references to somewhat fictional historical periods in which the UK was free from external influence,Footnote 96 and particularly to the loss of its Empire.Footnote 97

Fintan O'Toole describes the cultural background of this specific British narrative as the ‘pleasures of self-pity’, which involves two complementing parts: a deep feeling of loss and a simultaneous feeling of superiority.Footnote 98 The plot of betrayal in combination with victim myths and heroic stories is particularly relevant to populist narratives, as it not only mobilises collective emotions of anger, indignation, and pain, but even creates possibilities for agency.Footnote 99 The underlying demand that you as true representatives of the people need to reclaim your country (which otherwise will be lost) enables different, more positive collective emotions such as confidence and pride. While moderate British politicians try to tell the story of cooperation, mutual trust, and British benefits of being part of the EU, Brexiteers put emphasis on the dystopic fantasy of a battle against the EU as the incorporation of the German will to subject the British continent.Footnote 100 Populists therefore promise a political solution to the dystopian situation of hopelessness, humiliation, and vassalage. The heartland narrative shows how chosen body metaphors in relation to the nation and the people provoke collective emotions (fear and anger), strong moral judgements (elites as traitors), and feelings of self-enactment in terms of agency for ‘forgotten white men’. In terms of ‘the political’ logic, one would have to point out that the European Union has been a project that counters the negative effects of imperial expansion, whereas in terms of ‘the fantasmatic’ logic, an empire would blissfully replace the EU with the historical greatness merited by the British people. The idea of becoming part of an empire is therefore more pleasing and appealing than the reality of the European Union – even if upon further reflection, the re-establishment of an empire by any British party is an unlikely goal.

Proud Mothers

The second case is, at first glance, less concerned with a political message. Depicting a well-known (former) German politician of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party, the main message of this poster could be seen in simply advertising Frauke Petry, but nothing else. In the depiction of a woman with a child we identify a culturally appropriate motif, but less so a politically adequate one. As a way of sending a political message in the setting of a western European country, female politicians with children, particularly babies, are rather unfamiliar. As distinct to the threat of emasculation that fisherman Tony faces, women (almost as a continuation of children) in right-wing storytelling are primarily depicted as victims of foreign men, rather than by the EU or similar entities. In fact, the sample of posters we studied often showed these motifs, either as direct threats to women's/children's safety or as threats to their ontological security (for example, in the slogan ‘Bikinis instead of Burkas’ or posters in the aftermath of attacks on women in Cologne). In our analysis, we found that the majority of images by the Alternative for Germany (AfD) portraying women or children, for instance, point to the need to protect daughters and wives, who thereby become objects of masculine displays of strength.

However, images of women are never used to represent groups of men and women, such as employees, tax payers, etc., but only to represent other, equally vulnerable women. Interestingly, this does by no means reflect the fact that women are integral parts of the labour force and also receive social transfer benefits (like Tony) or that they could be won over as voters instead of their partners to whom appeals for women's safety seem to be addressed. Therefore, before even looking in more depth at the poster of Petry's, we contextualise it as an outlier in the clear gender division into males as agents and women/children as subject of politics. At the same time, it uses a completely different style from other posters that feature women, which show them in traditional folk costume, as objects of sexual desire or as primarily vulnerable to dark males. The neutral presentation is very much in line with how male professionals are presented and thus seemingly harmless. As part of its election campaign in 2017, one of the AfD's (former) leaders, Frauke Petry, posed with her own baby. The poster was somewhat scandalised for this reason, since utilising children for political gain was seen as overly strategic and immoral. Beyond this calculated move at publicity, our layered analysis helps to show what the image itself and the image/text combination offer in terms of potential appeal to the public.

Motherhood and politics

We see, at first, the female politician, looking into the camera with a calm, confident smile. Her short, severely cut hair and sparingly applied makeup as well as her modest business shirt do not distract from the main focus of the image: The baby, dressed in a neutral greyish top, is asleep and trustingly held by the mother, who displays her wedding band on the hand that holds the child. The background is kept neutral, in a greenish grey that creates no distraction from the mother with child. The skin-to-skin contact between mother and child, the protective hand on top of the baby's head, and the angle of the mother's head are visually arranged to a pleasing ensemble.

The abstract motif is well known in art and clerical history; the Madonna with child has strong cultural – Western, Christian – roots and is evoked here in the way mother and child pose. Even those not consciously engaged with the Church will have implicit knowledge about the motif in their cultural repertoire. Given the fact that Petry was married to a Christian parson, had four children with him, had an affair with another AfD politician, had the new child with him and was divorced and then remarried, the Madonna motif is an interesting choice. At the same time, the image conveys a sense of serenity, a unique mood that only a mother and baby can create. The universal love of babies provides affective triggers and an emotional storyline at the same time, even for those who may despise the politician. The image may serve to establish Petry's credibility as a party leader and to confer legitimacy as a caring mother. The image of the innocent child and devoted mother camouflages the fact that Petry was a known power politician and, in contrast with the regressive thinking of the party, herself a working mother. This needs further reflection.

Adding the textual layer, we read: ‘Frauke Petry, Chair of the AfD. And what is your reason to fight for Germany? Take courage, Germany’ [or, in a broader reading, ‘Get married, Germany’]! The belligerent slogan stands in stark contrast to the serene mood of the image and thus creates a productive friction. It directly addresses the audience, drawing it into a discussion. The slogan also works on a presupposition, that is, claims that every reader in fact wishes (or should do so) to fight for ‘Germany’. No further explication of the fight or even of the idea of ‘Germany’ is given, since the addressed audience apparently would not question the presupposition – or if they did, would not be the addressed audience.

The main implication of the slogan is that a mother should fight for the future of her child. The idea of ‘fighting’ forms a second fantastic layer in the already emotionally loaded image of a mother with her newborn child. It implies sacrifice, passion, and aggression – all for the sake of a future generation. Here, the heroism of a mother fighting for a child – by means of politics – renders political action a personal mission, a cause greater than that of candidates competing for office. The plot of a hero (or heroine, in this case) fighting against an enemy (possibly the foreign infiltration by migrants, many of whom are seen to have many children) for a true people is invoked. A heroine, it can be assumed, is more than a simple politician.Footnote 101 Petry presents herself both as a party politician (dressed as most other politicians from more established parties would) and as all (German) mothers; her reasons for pursuing politics are the purest. This mirrors what proponents of fantasmatic logic have claimed, namely that politics can be depoliticised to make it more palatable. The fantasy of politics without politicians – corrupt elites – underlies this imagery. Petry's dual role as politician and mother is what is meant to make her so convincing: she is not in politics as part of an egotistic struggle, but for personal reasons. The baby, as all true Germans would be, is in her care, and thus she can be trusted to fight for the people rather than for her own gain. The appeal therefore lies in believing that a party like the AfD seem less ambitious or less involved in petty struggles than other parties,Footnote 102 to which the AfD aims to become an alternative.

Figure 2. ‘And what is your reason to fight for Germany? Take courage, Germany’.

The fantasmatic appeal of the image and the broader narrative becomes tangible by understanding the near impossibility of having a negative reaction to the image of a mother with child. Even a controversial figure like Frauke Petry can expect to be respected as a mother, regardless of her political stance. The vulnerability of a mother with child serves as a protective shield against too harsh criticism. Only the slogan adds a political message to the otherwise depoliticised Madonna image. In conjunction with the benign image, the slogan is rendered less aggressive but also more credible. Different frictions characterise the poster and work in conjunction to offer different interpretive anchors that allow for a broader appeal. Traditionalists may applaud Petry for being a mother first and a politician on top. More nationalist supporters of AfD may welcome the not too subtle message that there needs to be a fight for Germany, which Petry will lead. The ‘proud motherhood‘ narrative both establishes the people – true ‘Germans’ – and the mode of doing politics – as a ‘fight’ for a just cause – and uses the symbolism of female roles of motherhood to bring the message home. Others may find it easier to vote for a former fringe party that manages to present itself so professionally, without reverting to unsubtle friend–foe imagery. All these and possible other interpretations buy into the fantasy that motherhood and nationalist politics are connected, but satisfy different needs with it.

We are not the elite

Similar to Donald Trump's, Matteo Salvini's, or Boris Johnson's attempts to present themselves above petty party politics, Petry being a mother immunises her from being suspected of serving self-interest. Thus, she is not just a politician, but more than a politician. The ‘Proud Mother’ narrative thus links up to a central tenet of populist, particularly right-wing parties across several countries, namely a ‘we are not the elite’ narrative.Footnote 103 Claiming to counter established, elite-driven modes of politics – embodied in such generalising metaphors as ‘the D.C. swamp’ or simply ‘Brussels’ – populist parties promise alternative, responsive modes of doing politics. At the same time, they must necessarily campaign to achieve power and, for instance, claim the White House – which means they have to reconcile two inconsistent messages. Furthermore, many of the candidates that claim to take an anti-elitist stance are clearly part of the elite themselves; Brexit campaigners like former Eton pupil Boris Johnson, trust fund baby Donald Trump, and second-generation party leader Marine Le Pen are white, wealthy, and come from well-connected, affluent families. Even current French president Emmanuel Macron, a former investment banker and ENA graduate, claimed to lead a ‘movement’ rather than a party in order to signal his departure from corrupt, inert party politics. As noted above, fantasmatic logic often functions to reconcile contradictory claims. One well-known example of an attempt to bridge such positions can be found in Donald Trump's public self-representation. Posing with his family in his lavishly decorated New York City apartment, Trump projected a public persona of a man wealthy and influential beyond measure. Already ever-present in the public eye as a television show celebrity, Trump presented the image of a somewhat vulgar (that is, relatable) public figure without any need to strive for the office of US president, thus conveying the underlying message that he had no other motivation for becoming a politician than ‘making America great again’.Footnote 104

Beyond this, the strength of the image under discussion here lies in its metaphors and implicit messages that make a world ruled by the parties advertised seem attractive to their voters; both to men, who struggle with their roles in modern societies characterised by calls for political correctness and claims for gender equality, and women who may thus reconcile their conservative beliefs with a politically relevant taskFootnote 105 – that is, not being just mothers, but mothers with a deeper purpose, namely the protection of a truly German people.Footnote 106 The silences created by this and similar posters as opposed to those used by other parties are also telling. Many centrist parties increasingly diversify their images in terms of ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, even clothing styles, and so on. Women of colour, gay couples, urban hipsters, and so on have become indicators of a diverse, open society promoted by most mainstream parties. They are almost entirely absent in the campaign posters of right-wing populists we found – repetitive patterns of showing blonde children, devoted mothers, women as helpless victims of foreign men, etc. reify reactionary images and mobilise those that feel threatened by diversity (summarised as the ‘new Germans’), new styles of living, and overall growing levels of equality. The fantasmatic appeal of an old-fashioned but time-tested lifestyle cannot be underestimated.Footnote 107 Fighting for these worthy causes is claimed to be a humanistic mission rather than politics, which is often portrayed as corrupt and self-interested in right-wing populist narratives.

Conclusion

We link up to discussions about the performativity of storytelling (in populism), and our main interest lies in narrative modes of political storytelling, which we approach through a visual narrative analysis. Therefore, we only generalise to the extent to which the material for our analysis allows it. At the same time, understanding the fantasmatic dimension of storytelling, which can be produced in metaphors, images, and symbolism, may tell us why some political stories, here those of right-wing populist parties, and even political claims can become so appealing.

A key finding, derived from both our consultation of the literature on narratology and the visual analysis, is the way storytelling can create fantasy by means of narration, for instance in the various ways of combining images with text. As the analysis shows, different layers of meaning can be combined to work together or develop productive friction. An important aspect of the fantasmatic appeal is that pleasure and thus, potentially, consent can be derived from a range of responses, ranging from self-pity to feelings of superiority, or often even in combination. The dual strategy of attempting interpretive closure and simultaneously leaving room for a variety of interpretations can be seen as an important dimension of the appeal that these narratives generate. Following from this, narratives may reach different, and possibly hitherto untapped audiences through fantasmatic appeal.

With regard to the research practices also interesting to scholars of International Relations, images provide easy and often intuitive access to much more complex narratives; they can also address politically precarious issues, which may even be taboo in public debates, more easily than explicit political narratives. This not only provides for responses that can help or even trigger identification, but also legitimises an overall political climate that is very concerned with sensitivities rather than problem solving. The storyline and the fantasmatic components of a narrative are therefore closely intertwined. One basis for appeal can be seen in generating conditions for agreement with the sentiment that is conveyed in images, which becomes a pleasant experience; intuitive agreement rather than rational self-persuasion can then create positive linkages towards a narrative or even the party that offers them. Agreement with the textual layer, which is often more explicitly political than the image, is another means of appealing to an audience, since further associations and references to underlying assumptions can be addressed.

Cultural repertoires, also mentioned above, provide points of reference that enable interpretation in particular contexts. The example of the Fisherman (Tony) makes more sense in the British context than, for instance, in an Austrian one. The addressees of the image require no explanation of the cultural context to understand the image and its broader narrative, as they are already part of the community they evoke. Exercises of identity building, therefore, as well as emotional consent with political narratives, presuppose a common understanding of some of the content and symbols, but are able to reconfigure them in new ways for exactly that reason. Political storytelling may not reveal all aspects of an agenda openly. Here, the use of imagery can be instrumental in getting more complex messages across, often those that go beyond an accepted political consensus. These moves, in turn, can influence the broader discourse and push the boundaries of what can be expressed freely. Even public outrage or criticism do not necessarily imply the failure of this strategy; withdrawing particularly scandalous images or deleting tweets can have positive repercussions, especially for extremist parties.

The layered interpretation process of the visual narrative analysis brings to light the productive interplay between images, narratives, and their fantasmatic dimension. The performativity of images and the interplay between image and text create emotionalised storylines, which often follow fantasmatic logics, mainly as attempts to remove them from the realm of power politics. Rewards for agreeing with political messages through pleasure may not be causes for assent, but certainly contributing factors. This hints at why it is vital and interesting to pay close attention to the interlinkages between images, fantasy, and political narratives.Footnote 108

Finally, while IR scholars have, so far, been hesitant to study the phenomena of populism, recent studies in IR demonstrate the strength that newer strands in the discipline have in providing instruments and a promising conceptual vocabulary (such as visuality, gender and violence, language, among others) that may generate fresh outlooks on the performative dimension of populism. IR scholars have thus an opportunity to become engaged in an interdisciplinary endeavour of understanding populism in its broader cultural and political context.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article were presented at two workshops on the concept of narrative in IR in Trento (October 2017) and Hamburg (August 2018) and at the BISA conference in Bath (2018). We thank participants in these events for their comments and suggestions. We are especially grateful to Felix Berenskoetter, Christian Bueger, Chiara de Franco, Maren Hofius, Vincent Della Sala, Elena Simon, Christopher Smith Ochoa, Daniel Orders, Sabrina Pischer, Sigrid Quack, Micheline van Riemsdijk, Christine Unrau, Daniela Weißkopf, and Wouter Werner for close critical readings and very helpful comments. Research for this article has benefited from support of the Centre for Global Cooperation Research at the University of Duisburg-Essen.