Introduction

It is hard to quarrel with the claim that liberal hegemony is eroding, and that this trend tears at the normative fabric of global governance.Footnote 1 Non-Western powers such as China, Russia, and Turkey are challenging liberal conceptions of global order by building alternative institutions and contesting some of the paramount principles upon which Western hegemony was built. Meanwhile, the rise of anti-liberal forces inside the West itself indicates that the challenge to contemporary global governance comes from within as much as from without. While a complete overhaul of the normative architecture undergirding global governance seems unlikely,Footnote 2 the decline of Western dominance is accompanied by increasing contestation over the meaning of key international norms.Footnote 3 There is less and less certainty that all actors mean the same thing when they invoke individual norms such as the Responsibility to ProtectFootnote 4 or norm sets such as those surrounding sovereignty, multilateralism, or human rights.Footnote 5 As a result, debates over norm polysemy – the parallel existence of diverging meanings or interpretations of norms – will become a central issue for research on norms and global governance in the years to come.

We suggest that norm research in International Relations (IR) is currently not well equipped to meet this challenge. Much of the existing research on norm meaning(s) is underdeveloped regarding both the ontological and conceptual foundations, and the normative evaluation of polysemy. With few notable exceptions,Footnote 6 this research has bracketed the question how norm meaning is constituted. Theoretical approaches, rationalist and constructivist alike (see below), are almost all based on an essentialist understanding of norms that either assumes that there is some essential, ‘true’ core to norms or, as in critical constructivism, that an intersubjective consensus on their meaning is at least theoretically possible.

To be sure, IR research on norms has made a significant contribution to our understanding of the role and (regulative and/or constitutive) effects of norms in international politics and thereby significantly enhanced our understanding of ‘norms as causes’.Footnote 7 However, by bracketing conceptual questions surrounding norm meaning, it has also narrowed the scope of norms research and foreclosed an investigation of certain aspects of norms and international norm dynamics. In particular, this omission has resulted in a conspicuous silence on the constitution, the effects, and the politics of norm meaning. Enlisting notions of strategic ambiguity and contestation, norms research has touched upon some of the symptoms of the constitution of norm meaning such as the possibility of divergent interpretations of a norm – the norm polysemy that IR scholars often study in terms of ‘contestation’.Footnote 8 But it has not systematically engaged with the structural conditions that underpin these processes of ‘meaning making’ and which make divergent norm meanings possible in the first place. Overall, this conceptual and ontological deferral has narrowly confined considerations of the politics of norm meanings to the instrumental value of norm determinacy and indeterminacy for the legitimacy or effectiveness of global governance.

In order to address these shortcomings, and to open up new avenues for research on the meaning(s) of norms in world politics, this article offers a reconceptualisation. We draw on poststructuralist and critical norm research to develop a radically non-essentialist understanding of norm meaning. Such an understanding breaks up the dichotomy between norm clarity and norm indeterminacy that often infuses existing approaches. More specifically, we argue that the diversity and co-existence of different norm interpretations – something we refer to as norm polysemy – is not (just) a matter of norm quality or linguistic precision. Instead, it results from two sources: the first, as contestation research contends, is a pluralisation of the interpretive contexts in which norm meaning is enacted – a condition reinforced by the decline of Western hegemony. The second – and this is something that existing approaches tend to miss – is the inherent openness of language, which induces an irreducible indeterminacy of norm meaning. We refer to this condition as norm ambiguity.Footnote 9 Tracing norm polysemy to the interplay of structural conditions of international society and the inherent ambiguity of norm meanings enables norm researchers to treat ambiguity as an inescapable feature of global governance,Footnote 10 the effects of which will increasingly come to bear in a post-hegemonic world.

Building on these ontological clarifications, we recast some of the debate about norms and global governance in a post-hegemonic world. We caution against the prevailing liberal angst about the future of world order, according to which re-establishing determinacy and consensus around liberal norms is necessary to avoid disorder.Footnote 11 We also reject a one-sided instrumental view of contestation as a tool to increase the legitimacy and effectiveness of global governance. Both these views ultimately, if to some extent inadvertently, see polysemy as problematic and sideline the politics and power relations inherent in attempts to fix the meanings of essentially indeterminate norms. By contrast, our approach puts the spotlight on the different mechanisms through which actors practically cope with the inherent ambiguity of norm meaning in different fields of contemporary global governance. Because ambiguity is a fundamental ontological feature of all norms, global governance actors are faced with norm polysemy all the time. A variety of contemporary governance mechanisms, ranging from third-party adjudication to ad hoc enactment, can be interpreted as ways of dealing with this challenge. As we demonstrate, these mechanisms have varying effects on power relations as well as questions of effectiveness and legitimacy in global governance. We conclude from this discussion that ambiguity is thus not inherently problematic: if channelled productively, it can help accommodate normative disagreement and facilitate the agonistic enactment of difference.Footnote 12

Our argument proceeds in three steps: Section 1 recaptures existing IR literature on norm meaning and points to some important limitations, with a particular focus on the relationship between norm polysemy and cooperation in institutions of global governance. Section 2 advances a radically non-essentialist understanding of norm meaning, according to which the empirical polysemy of norms is constituted by two conditions, context plurality and ambiguity. Section 3, then, discusses the implications of these conditions for global governance by identifying some of the mechanisms actors resort to in order to cope with norm ambiguity. The article concludes by pointing to the ethical implications of a radically non-essentialist conception of norms for IR norms research and for thinking about the future of global governance in a post-hegemonic world.

The meaning(s) of norms in International Relations theorising

The question how the clarity of norm meanings relates to the effectiveness and legitimacy of global governance has been one of the central issues within the IR debate about norms. The positions authors take in this discussion can be traced back to their meta-theoretical proclivities, with the main participants coming from either rationalist or social constructivist backgrounds.Footnote 13

Authors working within a broadly neoliberal institutionalist tradition frequently argue that norms facilitate cooperation because they constitute expectations about the behaviour of potential partners and thereby reduce uncertainty. The more precisely norms are formulated, the better they will be at informing the calculations of international actors, stabilising their expectations, and directing them towards collaborative behaviour. Imprecise norms, in this view, lead to imperfect information. They increase transaction costs and make enforcement through sanctions difficult because it is hard to determine whether a party has complied with agreements or not.Footnote 14 By consequence, norm imprecision may lead to unintended effects, subversion and, ultimately, the breaking down of cooperation.Footnote 15 To remedy these dangers, authors working within this tradition have treated the specification and codification of binding rules as an important catalyst of international cooperation. In this view, norm precision (or determinacy) is and should be one of the defining features of international law and institutions.Footnote 16 Any residual interpretative differences can and should be resolved by means of legal reasoning, in particular by investing interpretive power in independent judicial bodies, such as international courts and tribunals.Footnote 17 Put simply, difference in meaning ought to be ‘governed away’.

Authors coming from a social constructivist orientation have challenged this position. They highlight that formal legalisation is not the only or even necessarily the most important basis for legitimate and effective collective action in global governance. In their view, informal practices, arguing, and general beliefs about rightful conduct are equally important.Footnote 18 Therefore, norm-guided practice does not presuppose precision. To the contrary, precision can even have negative effects, for example by discouraging states from entering what they perceive as inflexible regimes or hegemonic frameworks imposed by powerful outsiders.Footnote 19 Formulations that are open to different interpretations, by contrast, may foster consensus among actors with a range of different predispositions.Footnote 20 This point of ‘constructive ambiguity’ is stressed, for example, in analyses of the European Union's (EU) Common Security and Defence PolicyFootnote 21 and the European Constitution process,Footnote 22 which both exhibit imprecise formulations but precisely for this reason managed to integrate the different views of the EU member states under a common framework. This resonates with Kelebogile Zvobgo, Wayne Sandholtz, and Suzie Mulesky's recent study of human rights treaty reservations, which shows how treaty provisions that create precise obligations enhance the likelihood of reservation.Footnote 23

The vast literature on norm contestation, translation, and diffusion, which emerged from a critical engagement with mainstream social constructivist norm research, has developed these ideas further. Rejecting the conventional constructivist idea of a linear norm cycle, in which norms emerge through argument and persuasion, and are then gradually formalised and diffused until their regulative effects cause significant shifts in state behaviour, the starting point of these approaches is the observation of continuous disagreement over the meaning of norms.Footnote 24 In this view, norms are contested ‘by default’.Footnote 25 The underlying assumption is that the emergence of global governance has lifted rule making and application out of the relatively homogenous cultural framework of the nation-state. International norms and their meanings are agreed upon in global elite communities but interpreted, negotiated, and applied in highly diverse cultural contexts. This process helps create a fit with local ideational predispositions but carries with it the potential for misunderstanding and resistance in global governance.Footnote 26

Rather than taking Western liberal interpretations of norms at face value, the contestation literature therefore suggests that norm research should look at the way in which norms and norm meanings are negotiated, translated, and/or localised in different settings.Footnote 27 The normative core argument of this literature is that making processes of norm building more inclusive – by increasing space for and access to contestation instead of relying on static interpretations – may impact positively on a norm's recognition and, by consequence, buttress the legitimacy of governance frameworks.Footnote 28 Despite its self-reflexive and critical approach to norm meaning, the contestation literature remains broadly tied to a conventional, liberal approach to global governanceFootnote 29 that focuses on participatory processes of deliberation within an already existing realm of difference. As we argue below, it is equally important to look into how this difference is constituted in the first place.

Buried within the contestation approach is an emphasis on social practice. Indeed, as we will show later, practice is important for understanding the inherent ambiguity of norm meaning. However, practice theorists have so far avoided a direct engagement with the notion of norm meaning. The reason for this, as Christian BuegerFootnote 30 observes, is that norms in the practice literature are typically seen as one component of practical knowledge, alongside other forms such as ‘rules of thumb, body-based performances, or knowledge inscribed in artifacts’.Footnote 31 Bueger points to the potentially fruitful ways in which practice theory and norm contestation scholarship can learn from each other, but ultimately acknowledges that practice theorists have so far seen little need to engage systematically with the constitution of norms, for the latter are only one feature of the spectrum of practical knowledge they are interested in.

The distinction between neoliberal institutionalists championing norm clarity and social constructivists as well as contestation scholars highlighting the benefits of interpretive openness is obviously a picture painted with a very broad brush. On the one hand, some constructivist works also describe clarity and determinacy as an essential precondition for the legitimacy and effective functioning of norm regimes.Footnote 32 Vague norms increase the likelihood of contestation once they are adopted, which can be a challenge for governance structures and may therefore prompt actors to try and create more specific regimes to pin down a particular interpretation.Footnote 33 On the other hand, rationalist studies of legal uncertainty due to institutional overlap and ‘incomplete contracting’ – the inclusion of vague language or provisions which are open to re-negotiation in international agreements – found that imprecise rules may be conducive to cooperation because they better reflect actors’ preferences in complex environments and uncertain futures.Footnote 34 Precision might also be detrimental from a rationalist point of view when it creates loopholes and leads to over complex provisions, which are vulnerable to manipulation and exploitation by those few experts who understand them.Footnote 35

Despite their differences, however, all three approaches – rationalism, social constructivism, and contestation research – share certain premises that limit their exploration of norm meanings. They assume that actors can collectively determine the meaning of norms in more or less specific ways by opting either for a formal-bureaucratic approach to cooperation, which is supposed to eliminate interpretive differences, or a more flexible, political approach. Choosing the latter, actors may, for example, strategically include vague terms in international agreements.Footnote 36 They may also create inclusive international institutions as a way to encourage deliberation, as often suggested in the contestation literature. This perspective foregrounds the value of using polysemy instrumentally as a way of maximising either individual actors’ gains, consensus during negotiations, or general norm compliance. Insofar as there is a normative evaluation, it accounts for norms as a means for realising external values such as cooperation, peace, and consensus. As it were, the precision of norm meaning is merely an intervening variable or, from a normative point of view, a means to the end of increasing the legitimacy or effectiveness of global governance.

While work under this broad paradigm has generated invaluable insights into the connection between the meaning of norms and the legitimacy of global governance, it leaves open a number of important questions. Above all, if norm meanings can be collectively determined in more or less specific ways, does this imply that behind a layer of contested meaning, there is an ‘essential’ meaning to every norm that actors (as well as observers) can approximate to or deviate from as they wish? That certainly seems at odds with the constructivist ontological notion that meaning is a contingent social construction and only exists as meaning-in-use.Footnote 37 If, on the other hand, interpretative openness is not simply the result of a conscious deviation from a given, ‘essential’ meaning, where does it come from in the first place? If we want to analyse how governance becomes possible and legitimate despite the disagreement on its normative foundations, we need to clarify what it is about norms that enables divergent interpretations in the first place.

The constitution of norm meaning: Distinguishing norm ambiguity and norm polysemy

The reason why existing approaches have trouble answering the questions mentioned above is that they do not go ‘all the way down’ when it comes to theorising the constitution of norm meanings. Critical norm research has highlighted that even the contestation literature, which is arguably most aware of the ubiquity of diverging norm interpretations, ultimately relies on an essentialist understanding of norms. As Holger Niemann and Henrik Schillinger conclude in a critique of Antje Wiener's pioneering work on norm contestation, ‘while the argument begins with an explicit rejection of an ontologisation of norms as facts, the conceptual shift to cultural validation leads to a re-ontologisation of norms and a problematisation of contestation’.Footnote 38 By adopting the social constructivist definition of norms as shared standards of appropriate behaviour, the contestation literature posits the researcher as an objective observer of the pre-existing identity of norms and invites an epistemological stance that treats ambiguity as something problematic.

To this epistemological point, we would add a conceptual shortcoming. Although the contestation literature emphasises the dual quality of norms as structuring behaviour and being structured by it,Footnote 39 it has not adequately theorised the relationship between the practice of contestation as a source of different, co-existing norm interpretations (what we will refer to as norm polysemy), and the essential indeterminacy or ‘contestedness’ of norm meanings (what we will refer to as norm ambiguity). The result is a somewhat paradoxical stance that promotes contestation (in the sense of deliberating norm meanings in a Habermasian sense) as a means to overcoming the conflictive potential of contestedness (in the sense of stunted norm recognition and validation).Footnote 40

To open up norms research to more critical perspectives, Stephan Engelkamp and Katharina Glaab have called for a conceptual rethinking of norms ‘in a more reflective way that tolerates and even embraces normative ambiguity’.Footnote 41 Taking up this challenge, we propose a coherent conceptualisation of how norm meaning is constituted as a basis from which to lift the debate about the implications of norm polysemy for global governance out of its confinement to instrumentalist terms. At its core, this approach sees the empirical polysemy of norms as constituted by two conditions, namely context plurality and ambiguity.

As indicated above, context plurality is a well-established source of polysemy. Contestation scholars have long pointed out that the enactment of norm meaning is not carried out in a social vacuum but in specific cognitive or cultural contexts. These frames provide interpretive grids based on which actors can turn a norm into meaning-in-use.Footnote 42 If actors enact norms from within diverging discursive grids, this will result in norm polysemy. Empirical studies on norm contestation have provided rich insights into how norm polysemy permeates fields like armed conflict,Footnote 43 non-proliferation,Footnote 44 or human rights.Footnote 45 In all of these cases, polysemy ensues in disputes over norm meaning, that is, dynamics of contestation.

Adopting this contextual view of norm meaning implies that when it comes to analysing the structural consequences of the meaning(s) of norms in global governance, examining the context of its institutionalisation should assume priority over studying the supposed ‘substance’ of a norm or formal attributes such as its lexical precision. Acknowledging the role of context in the constitution of norm meaning implies that the degree of polysemy does not necessarily decrease as one moves from fundamental principles to more specific rules and procedures, as most norm researchers – including some contestation scholarsFootnote 46 – assume. Rather, it depends on the degree of differentiation of the traditions and historical practices of interpretation that underpin the contexts within which actors enact norm meanings. The result, as Christian Reus-Smit observes, is a ‘highly complex cultural universe of meanings and practices: neither a world of a single norm … nor a world of coherent cultural structures’.Footnote 47

However, focusing on context alone does not explain why a norm allows different actualisations in the first place. Without answering this question, research risks re-ontologising – or re-essentialising – norms as signs with real-world referent objects, which are related by means of definition and deliberation – processes the researcher either performs herself or extrapolates from the deliberations of the actors themselves who can, at least in theory, achieve an intersubjective consensus over norm meanings. Approaches that confine the theorisation of norm meanings to the level of structural context, like most contestation literature, ultimately maintain a truncated understanding of the constitution of norm meanings.

This brings us to the second part of our conceptualisation, ambiguity. Philosophers of language and poststructuralist scholars from across the social sciences have frequently asserted that all meaning is principally indeterminate.Footnote 48 Because all ‘signs’ (words, names, concepts) lack a definite ‘signified’ (empirical referent object), there is no objective and definite meaning hidden in language that actors could simply uncover through interpretation. Instead, signs subsume multiple, equally valid meanings and can be understood to refer to different types of actions or practices.

So how is ambiguity implicated in the constitution of norm meaning? The principal mechanism at play is linguistic practice.Footnote 49 According to Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose ideas have been enlisted by the early constructivist pioneers such as Adler, Onuf and Kratochwil,Footnote 50 ‘the meaning of a word is its use in the language’.Footnote 51 While the concept of ‘meaning’ and its source has a rather ambiguous status in Wittgenstein's work, he was clear that the meaning of a word (or a sentence) remains fundamentally undetermined. The idea that meaning is always relational and never absolute is encapsulated in his concept of ‘language games’ developed in the Philosophical Investigations. Because meaning is not inherent in words, it has to be constructed through (linguistic) practices in which actors determine the meanings that attend words. The key point here is that although language games are governed by a system of rules that allow actors to identify similarities and dissimilarities in meanings, their interactions cannot produce precise links between words and meanings that lead to ‘a state of complete exactness’.Footnote 52 The basic problem, Wittgenstein noted, is that ‘we do not command a clear view of the use of our words’, leaving us with ‘perspicuous representations’ rather than clear correlations between words and meanings.Footnote 53

We can surmise that Wittgenstein's claim about the fundamental indeterminacy of linguistic concepts also extends to norms. The meaning of norms is only rendered observable through their social enactment, in which actors temporarily ‘articulate’ it. Norm meaning is, in other words, always meaning-in-use beyond which no ultimate truth lies.Footnote 54 Consequently, the prescriptions of appropriate behaviour a norm entails can never be inferred from one particular meaning, and neither can the grounds for its application, justification, and contestation. They emerge and evolve through complex and often unpredictable linguistic practices. We call this ultimate indeterminacy of norms, engendered by the indeterminacy of language, norm ambiguity.

The notion of ambiguity debunks the idea that norms possess anything like an essential ontological core. Borrowing from Alexander Wendt,Footnote 55 without context-specific enactment, a norm is merely a ‘potential’ (containing multiple potential meanings) whose concrete meanings – as well as the practices they prescribe – cannot be determined. Consequently, enacting a norm contains an element of ‘decision’ that is not structurally determined itself.Footnote 56 Similarly, assessing norm compliance under conditions of norm ambiguity is also never an objective practice, in which an impartial adjudicator determines whether an action falls within the perimeters of acceptable behaviour as foreseen by the norm. Instead, assessing norm following behaviour always includes an element of actualising – not simply interpreting in the sense of ‘clarifying’ – the meaning of an otherwise ambiguous norm. Any such actualisations can only be partial and temporal.

Conceptualising norm ambiguity in this way explains both why norm contestation is possible in the first place, and why it can never rid norms of their ‘contestedness’. It thus helps understand struggles like that over the prohibition of torture in the context of the US ‘war of terror’. The very possibility of the attempt by the US administration to ‘redefine’ the content of the norm and the ensuing struggle over the meaning of the norm shows that, despite its standing as a jus cogens norm and numerous attempts to clarify and specify its content, the norm remains open to diverging interpretations.Footnote 57 Due to its inherent ambiguity, the norm subsumes multiple meanings that actors, in this case the US administration, can invoke in a bid to define (or contest) ‘the’ meaning of the norm.Footnote 58

The poststructuralist monition about the contingency and instability of all attempts to fix meaning thus relates the failure to control norm meanings and to forge consensus to their inherent ambiguity. As Zygmunt Bauman observes, efforts at resolving ambiguity by adding additional layers of norms only ever result in ‘yet more occasion for ambiguity’.Footnote 59 Attempting to specify general principles through the codification of ever-more detailed prescriptions, does not fundamentally alter, nor does it bring to a halt, the inherent ambiguity of normative language.Footnote 60 Writing on the role of language in the interpretation of international law, Ingo Venzke has captured the essence of this perspective quite neatly when he stated that ‘any rule – generally, x counts as y in context c – will be troubled by indeterminacy’.Footnote 61 Technocratic rules and procedures still rely on contingent enactments in their application.

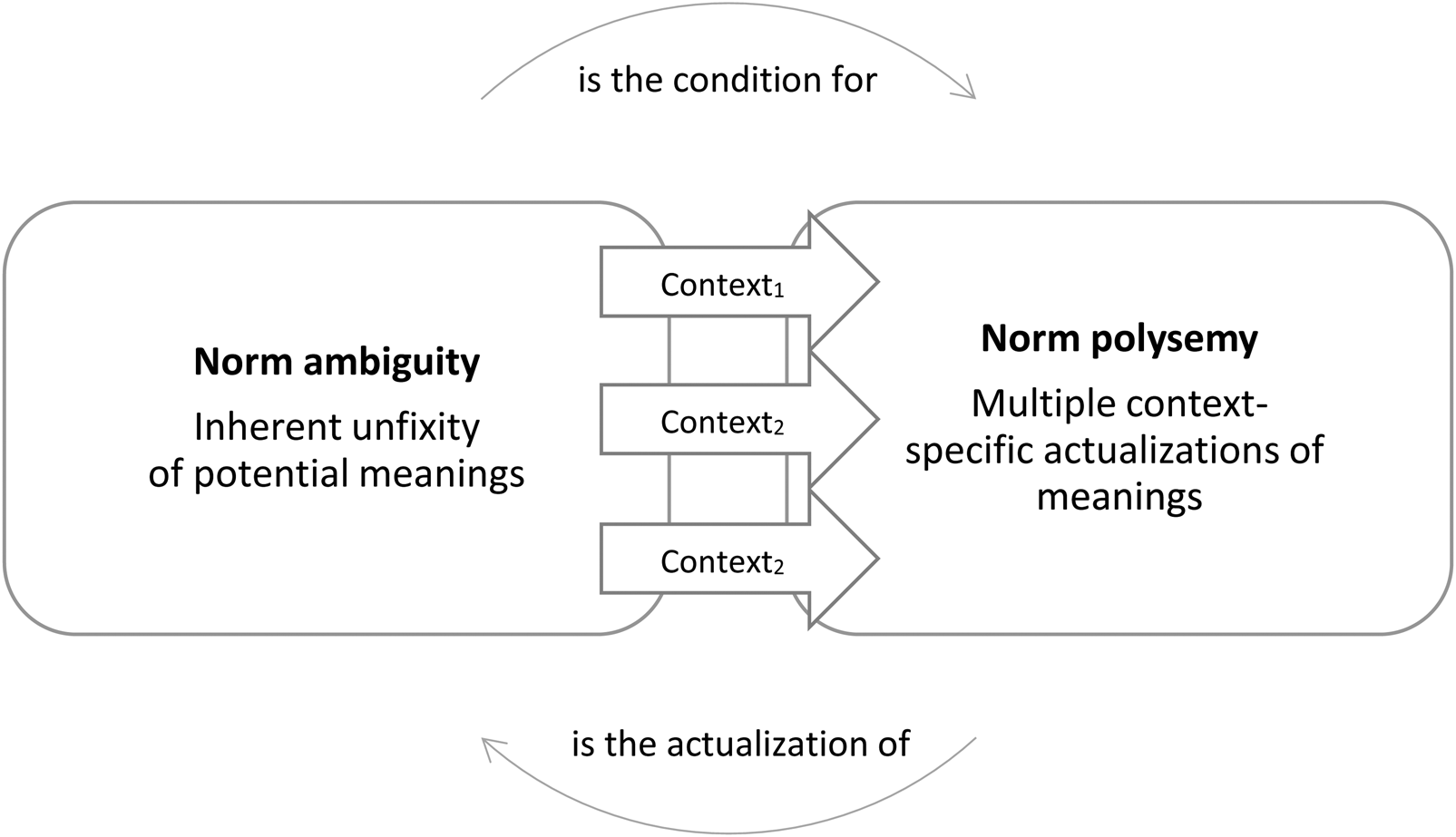

To sum up, our conceptual framework sees norm polysemy as resulting from the interaction of two constitutive conditions: the fundamental indeterminacy of language (ambiguity) and the differentiation of contexts in which meanings are actualised through contested processes (Figure 1). It is the interplay between ambiguity and context that makes actualisations of meaning possible, as the interpretation of the language of a norm necessarily takes place in context, be it cultural, institutional, social, or otherwise. Consequently, the meaning of a norm cannot be found anywhere but in its interpretive enactment. At the same time, the contingent nature of this enactment implies that there is no essential and stable meaning of a norm.

Figure 1. The relationship between ambiguity and context as sources for polysemy.

What does such a radically non-essentialist understanding of norms mean for the conventional notion of norms as shared understandings? We agree with Allan Collins that norms ‘need not imply a specific, even agreed upon understanding, but rather a vague and possibly incoherent understanding’ that evolves within certain parameters.Footnote 62 This chimes well with our conceptual reorientation, for it shifts the ontological core of norms from shared meaning to shared process. Locating the ‘sharedness’ of norms in process opens the door to consider norms as ‘social action fields’ rather than discrete social entities. Building on Neil Fligstein and Doug McAdam,Footnote 63 we conceptualise norms as social fields in which actors are attuned to one another on the basis of notionally shared understandings about the need for, and purpose of, a norm. For example, the prohibition on the use of force can be understood as a norm because actors agree that the resort to violence in international relations needs to be limited, while preserving the right to defend themselves and others individually or collectively. Within such a field, actors do not have to agree on shared meanings; instead, they need to acknowledge that the diverse ways in which norm meanings are enacted by others are ‘close enough’.Footnote 64 Accordingly, ‘sharedness’ as a characteristic feature of norms results from practices of recognition of diverging understandings. Polysemy, then, refers to a constellation in which actors placed inside a particular social field acknowledge the multiplicity of interpretations of this standard. Whether or not multiplicity subsequently gives rise to contestation, that is, disputes over norm meaning, then depends on whether actors problematise this multiplicity or challenge its boundaries.

Inherent in the idea of norms as social fields marked by polysemous meanings is the existence of boundaries. Indeed, as Carla Winston indicates, any interpretation that, in the eyes of the actors, does not address the general problem that motivates the norm or invalidates its functional purpose cannot belong to the field.Footnote 65 To invoke the example of the prohibition of the use of force again, interpretations that construe the waging of aggressive war as appropriate behaviour do not fall within the range of acceptable interpretations of the norm. The boundaries in which norm meanings exist are highly fluid, subject to ongoing adaptive processes. In this sense, our conceptualisation of norms as social fields shares similarities with recent pragmatist approaches to normativity, because it sees norms as arrangements of processual, interacting interpretations of meanings aimed at directing action toward the attainment of a specific set of regulative outcomes.Footnote 66

Thus, ambiguity does not rule out that actors accept the existence and validity of a norm as a basis for coordinated action even as their understanding of its precise meaning will be different. But we do maintain that problematising the constitution of norm meaning ‘all the way down’ raises questions about the politics of norm meanings that existing IR norms research has failed to answer. The next section, therefore, offers a framework for theorising and empirically analysing the implications of norm polysemy for global governance.

Global governance under conditions of norm polysemy

Considering context plurality and ambiguity as inescapable conditions of norm meanings has deep implications for how we study the role of norms in global governance. In particular, it suggests to theorise the practices through which actors cope with norm polysemy as central, and in fact, constitutive processes of global governance. If there is an inherent element of ambiguity to norms, then coordinated action depends not on the ability to fix their meaning, as dominant approaches to global governance suggest, but on mechanisms to cope with their persistent indeterminacy. Different coping strategies may have important effects on relations between actors of global governance, as well as the effectiveness and legitimacy of governance itself.Footnote 67

In this section, we use empirical illustrations from different areas of contemporary global governance to introduce four mechanisms that we see as characteristic institutional solutions for coping with norm polysemy: deliberation, adjudication, uni- or minilateral fixation attempts, and ad hoc enactment. While often designed to do so, the actual function of these mechanisms is not to stabilise meaning. Instead, they structure the fields of norms by defining valid modes of discourse (thereby putting in place the language games in which actors construct and struggle over norm meanings) and providing repertoires for the enactment of norm meanings – ‘what tactics are possible, legitimate, and interpretable for each of the roles in the field’.Footnote 68 The governance areas from which we draw our insights are African peace and security, state conduct in the cyber domain, and international criminal justice. All three areas are characterised by intense norm contestation, the main fault lines of which run between representatives of the Western-dominated liberal international order and emerging or peripheral actors. For this reason, they are promising starting points for an exploration of the politics that infuse processes of coping with norm polysemy. Following the discussion of the different mechanisms, we briefly highlight some implications for power relations, legitimacy, and effectiveness.

Deliberation

Deliberative mechanisms aim to find consensual interpretations of norm meanings through argumentative reasoning. Rooted in a Habermasian concept of discourse,Footnote 69 this is the coping mechanism that comes closest to the ideal of many social constructivists and contestation theorists. The logic of deliberation as a coping mechanism rests on the assumption that, by communicating about their respective interpretations of a norm and trying to persuade each other of the merits of that interpretation, actors’ perspectives would eventually converge sufficiently to allow coordinated action.

An example is the process of devising norms for state conduct in the cyber domain in the UN framework.Footnote 70 Responding to growing awareness about the implications of the rise of digital Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) for international security, in 2003 the UN General Assembly's First Committee convened the first in a series of Governmental Groups of Experts (GGE). The purpose was ‘to consider existing and potential threats in the sphere of information security and possible cooperative measures to address them’Footnote 71 as well as, in later sessions of the GGE, to foster consensus on fundamental rights and responsibilities (‘norms, rules, principles’) of states in the cyberspace.

After overcoming initial obstacles, early rounds of the GGE process seemed to indicate incremental progress towards a common normative framework. A major breakthrough occurred with the 2013 consensus report,Footnote 72 which confirms that international law applies to the cyber domain. Far from signalling consensus (that is, ‘shared understanding’), however, this assertion has given rise to the more vexing question of how international law applies to the cyber domain.Footnote 73 There is an ongoing disagreement over what fundamental norms of international law like the right to self-defence mean in cyberspace.Footnote 74 Whereas some actors (primarily the Western states) advocate the applicability of the self-defence norm to the cyber domain, others (notably China) vehemently oppose it. At the heart of the conflict lie interpretative differences over what constitutes an armed attack in the cyber domain and, by implication, under which conditions the norm authorises the use of force in response to a cyberattack. In other words, by now, interpretative challenges resulting from norm polysemy, and at a more fundamental level from norm ambiguity, have assumed the centre stage in the process.Footnote 75

The disagreements over norm interpretations are of such extent that they even caused the GGE process to come to a temporary halt in 2017, when the fifth GGE could not agree on a consensus report. While the deliberative approach has structured the field in which different norm interpretations are enacted, it has not achieved the purpose of creating ‘shared understandings’. Even though the process was resumed in 2019,Footnote 76 expectations regarding its effectiveness remain modest and, as reflected by the establishment of a more inclusive Open Ended Working Group,Footnote 77 which convenes in parallel to the GGE, the legitimacy of the GGE process is increasingly being challenged. As such, the UN-centred process of regulating state conduct in the cyber domain provides an illustrative example of actors attempting to cope with ambiguity, and norm polysemy, using deliberation, as well as the repercussions this choice of mechanism entails for the effectiveness and legitimacy of the process.

Adjudication

Global governance actors can invest the power to interpret norm meaning in judicial bodies. The rationale is to remove the decision over meanings from the supposedly detrimental influence of politics to the realm of legal arguing. The ostensibly objective character of legal modes of reasoning is supposed to legitimate such decisions. This idea, well established in International Law scholarship and IR work especially in its liberal institutionalist variant, underlies the creation of international courts and a plethora of dispute settlement mechanisms. From this point of view, international courts exercise a distinct public authority on behalf of the international community that allows them to stabilise normative expectations.Footnote 78

Some of the most high-profile instances of coping with polysemy through adjudication are the disputes over the meaning of sovereign immunity, one of the foundational norms of international law. Challenges launched against the ICC especially by African states have exposed the limited success of efforts to specify the meaning of sovereign immunity through codification in the Rome Statute.Footnote 79 After failed attempts to find consensus through deliberative mechanisms like the ICC's Assembly of State Parties,Footnote 80 African states tried to shift the dispute from the political to the legal realm by suggesting that the International Court of Justice (ICJ) provide an advisory opinion on the matter of the sovereign immunity norm.Footnote 81 High-level AU representatives have recently indicated that they are willing to accept the ICJ's opinion, whether it endorses their interpretation or not.Footnote 82 This demonstrates the potential of dispute settlement mechanisms to provide interpretations of norm meaning that are considered authoritative even if they are not shared. Such mechanisms require, of course, that the involved parties accept their authority – an issue we will briefly return to below.

Uni- or minilateral fixation attempts

Many of the problems that deliberative and legal modes of coping with divergent norm interpretations encounter can be understood as consequences of context plurality and ambiguity, the two constitutive sources of polysemy. When the shortcoming of multilateral processes become apparent, actors or groups of actors can attempt to assert their interpretation as valid, while denying the validity of competing norm meanings. This can either come in the form of unilateral statements promoting certain interpretations or choosing exclusive discursive arenas to reduce context plurality.

For an example of the first variant, we can turn to the polysemic norm of subsidiarity in African peace and security governance. The norm is supposed to clarify the authority relations between the UN, the African Union, and the subcontinental organisations (Regional Economic Communities, RECs) by envisioning a division of labour according to the principle that conflict responses should be as local as possible, as international as necessary. Even though it projects such a neat conceptualisation, attempts at putting the subsidiarity norm into practice have been stunted by diverging interpretation of its meaning. In this context, actors have reverted to unilateral attempts to fix meanings, which expressed their quest for organisational autonomy.

The AU in particular has advanced an understanding of subsidiarity as a means of asserting its ownership and authority over African peace and security affairs, and of securing material support from the UN.Footnote 83 Officials of the AU and its member states felt sidelined by the UN and Western actors in conflict resolution in Libya, Mali, and Sudan. Against this background, the AU Peace and Security Council asserted that subsidiarity implied ‘consultations prior to decision-making … and effective use of the comparative advantage of the AU and its Regional Mechanisms for Conflict Prevention, Management and Resolution’.Footnote 84

Interestingly, the AU has shown inconsistencies in its interpretations of the norm when it comes to its ‘upwards’ relations with the UN versus its ‘downwards’ relations with the subregional RECs. Towards the latter, the AU emphasises its supreme authority to rebuff an unchecked devolution of peace and security competences.Footnote 85 This interpretative ambivalence appears especially stark as the same governments promote different stances depending on the organisational venue,Footnote 86 which demonstrates the strategic and political nature of struggles over norm meanings.

The second variant, switching from broad global mechanisms to more exclusive formats, is exemplified by more recent developments in the cyber norm process. In light of the temporary breakdown of the GGE process and the continual contestation over norm meanings, state actors have increasingly turned to ‘like-minded’ groups such as the group of Western states, or regional organisations like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) centred on China and Russia. The hope is that ‘common understandings’ are more readily available, and agreement can be more easily reached inside these less-than-universal formats with their more homogeneous membership. The retreat to more exclusive formats with more homogenous interpretative contexts is an attempt to circumvent the ‘interpretative challenges’ the GGE process has run into. However, the ultimate effect of this strategy is not an eradication of norm ambiguity, but the constitution of a new field for enacting norm meanings that includes agents, modes of discourse, and action repertoires that are more amenable to certain actors’ dispositions.

Ad hoc enactment

This mechanism differs from the former three in that it does not rely on the assumption that there is an objectively attainable, fixable meaning behind the polysemic norm. It is therefore possibly the one that comes closest to acknowledging – though not necessarily by design – norm ambiguity as a constitutive condition of global governance. Instead of trying to govern polysemy away, actors strike temporary and pragmatic bargains that enable cooperation on the basis of a common understanding of ways of action, without attempting to resolve the underlying disagreements over norm interpretation once and for all.

Turning back to African peace and security governance, we find that ad hoc enactment has been a consequential way for the involved organisations to ensure cooperation in addressing crises despite the inability to settle differences over the meaning of the subsidiarity norm. Inter-organisational cooperation on African peace and security challenges have followed a largely situational logic, in which the concrete circumstances of the crisis at hand shape how conflict resolution strategies are devised.Footnote 87 For example, the creation of a hybrid UN-AU Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) was crafted in response to the unique conditions of the conflict, including the shortcomings of the initial AU-led mission in the region, pressure on the UN to engage by transnational civil society campaign, and Karthoum's rejection of non-African troops on Sudanese territory.Footnote 88 In other cases, the organisations have opted for the sequential or parallel deployment of missions. Accordingly, many official documents by the UN and the AU emphasise flexibility in the interpretation and application of subsidiarity instead of offering any final definitions and operationalisations.Footnote 89

Coping with norm polysemy: Reflections on power, effectiveness, and legitimacy

The overview of existing norms research in IR in the first section has demonstrated that this body of scholarship is permeated by sweeping claims regarding the effects of polysemy on the effectiveness and legitimacy of global governance.Footnote 90 It seems to assume that the clarity of norm meaning – and therefore the absence of polysemy – is a possible, necessary, and desirable condition for global governance. Our illustrations here suggest instead that the implications are much more contingent and ambivalent. Above all, they depend on the mechanisms through which actors cope with differences over norm meanings, and on the politics that infuse these processes.Footnote 91

For example, many liberal thinkers regard deliberative processes as highly legitimate. However, the crisis of global multilateralism shows that such mechanisms seem to be less and less able to deal with context plurality. Illiberal governments, emerging states, and critical non-state actors challenge Western liberal standards of legitimacy. The ability of consultative mechanisms to produce a viable environment for enacting norm meanings under these conditions seems to be eroding, as the example of the GGE in the cyber realm suggests. In the liberal tradition, legal reasoning as a mode of deciding norm meanings is often the natural resort in cases where deliberation fails. International courts and dispute settlement mechanisms may acquire a high degree of legitimacy, but as Andreas Follesdal's cursory inspection of the landscape of international courts and tribunals suggests, they still face significant legitimacy problems.Footnote 92

In addition, due to the lengthy nature of adjudicative processes, their ability to provide timely solutions to situational differences of interpretation is limited. This is not to say that international courts cannot and should not play a significant role in governing the ambiguity of norm meaning. The ICJ's judgements in cases such as Wall, Military and Paramilitary Activities in and Against Nicaragua and Armed Activities on the Territory of the Congo, for example, have significantly shaped the boundaries within which debates about the meaning of the norm of self-defence take place.Footnote 93 But to further enhance the role of international courts in addressing governance challenges stemming from multiple interpretations of norm meaning (that is, polysemy), we need to address their multiple legitimacy problems.Footnote 94

Uni- and minilateral fixation attempts, meanwhile, may be a way of asserting authority and ‘resolving’ differences within a short timeframe. Moreover, they can engender powerful moments of resistance, where hegemonic meanings are rejected, and alternative visions projected. However, they are equally available to dominant actors as ways to enhance their hegemony, especially if they declare their interpretations as universal. In such cases, shifting debates about norm meaning to legal modes of arguing can change the workings of power in a way that empowers marginalised agents and their interpretations. Furthermore, the exclusionary nature of uni- and minilateral attempts may make it harder to cooperatively address governance challenges, thus reducing the effectiveness and, possibly, the long-term legitimacy of governance mechanisms.

Finally, ad hoc enactment on the basis of strategic situational convergence is highly volatile. This makes it an inept solution for problems that require long-term engagement, such as community-based development or postconflict peace building. At the same time, our conceptualisation highlights some advantages. The pragmatic orientation of ad hoc enactments may provide a way forward when other mechanisms reach an impasse, as in the case of inter-organisational African peace and security. Since it does not discriminate between norm interpretations, ad hoc enactment provides a space for enacting difference while still enabling coordinated action. Assuming the possibility of an essential meaning of norms can easily lead us to dismiss ad hoc cooperation as a deficient, second-best option to institutionalisation. From our point of view, it is precisely because it does not rely on this possibility and accepts the pragmatic notion of norm meaning as relational that ad hoc enactment becomes a viable mechanism for coping with norm polysemy in global governance. Instead of trying to govern ambiguity away, ad hoc enactment embraces the ambiguity underlying norm meanings without giving up on the project of global governance altogether.

As intuited at various stages, power, and the distribution thereof within different governance contexts, will have an impact on the effectiveness and legitimacy of these coping mechanisms in some way or another. It is beyond the scope and purpose of this article to address the relationship between power and ambiguity in detail, but a brief look at the norm literature suggests that the relationship is not as straightforward as it may seem. Many scholars have agreed that power resources – including material, institutional, and discursive ones – are critical to the evolution of norm meaning.Footnote 95 Indeed, considering the example of self-defence again, Dennis R. Schmidt and Luca Trenta have shown how the US's reinterpretation of the meaning of imminence has been adopted by many other states, including both US allies and non-Western powers.Footnote 96 This is in line with theoretical work that sees certain (powerful) actors as critical to the evolution of norms.Footnote 97 However, our conceptualisation of coping mechanisms suggest that power is not just an external resource that actors bring to the table to underscore the validity of their norm interpretations. By structuring fields for the constitution of norm meaning that follow distinct modes of discourse and engender specific repertoires for their enactment, different coping mechanisms affect the very way that power operates in these processes. Following Michael Barnett and Raymond Duvall's argument that ‘social structures and processes generate differential social capacities for actors to define and pursue their interests and ideals’,Footnote 98 we can surmise tentatively that the argumentative mode of discourse in deliberative mechanisms favours persuasive power; adjudicate mechanisms put a premium on the ability to exploit formal rules through legal expertise and reasoning; attempts at uni- or minilateral fixations engender compulsory and institutional power for the mobilisation and orchestration of consent through material incentives or force; and ad hoc enactments rely on something akin to network power. These productive effects differentially empower certain actors over others, and improving our understanding of these dynamics should be a central concern for IR norms researchers going forward.

This brief discussion can only point to some of the implications of different coping mechanisms for global governance. A systematic exploration will require the development of more elaborate normative criteria for the evaluation of effectiveness and legitimacy of coping mechanisms. It will also have to determine whether concrete effects may depend on different stages in the ‘norm life cycle’, such as emergence, diffusion, or institutionalisation. Our intention here is merely to open up the debate on the implications of norm polysemy by mapping a (not necessarily exhaustive) spectrum of possible coping mechanisms, thus substantiating our claim that the effects of ambiguity and polysemy are neither inherently good or bad, but depend on the ways in which global governance actors cope with them.

Conclusion: Norms and normativity in a post-hegemonic world

We argued in this article that IR norms research has not fully explored how norm meanings are constituted in world politics. More specifically, current debates on norm meaning(s) remain underdeveloped regarding both the ontological and conceptual foundations, and the normative evaluation, of polysemy. This has led to a stunted theorisation of the implications of norm polysemy, that is, the existence of diverging and competing norm interpretations, for global governance. While some constructivist approaches and contestation theory acknowledge the role of context plurality as a reason why actors understand norms differently, ambiguity as an equally important source of polysemy has not been systematically explored. We offer a framework for thinking about norm polysemy as constituted by both context plurality and ambiguity. This approach discards any residual notions of ‘real’ meaning behind norms and instead emphasises their inherent indeterminacy. As a fundamental condition for global governance, norm polysemy has important implications for the possibility of global governance. But unlike existing IR norms research usually claims, these implications are neither inherently good nor bad, but contingent on mechanisms actors put in place to cope with the polysemy of norms. We distinguish four such mechanisms and discuss their consequences for the effectiveness and legitimacy of global governance.

Our discussion clearly dismisses the idea of a silver bullet for dealing with norm polysemy in world politics. All the mechanisms we identify can enhance but also undermine the effectiveness and legitimacy of global governance. At the same time, a detached normative relativism is unlikely to drive the debate forward. We are deeply sceptical about strategies of trying to ‘govern away’ polysemy through hegemonic fixations or deliberative processes that pursue the idea of a neat interpretative consensus. Trying to suppress the inherent ambiguity of norms is likely to prove illusionary and prompt resistance in a world that is characterised by an increasing acknowledgement of difference. Since an element of ambiguity is inherent to all norms, overestimating actor control over norm meanings and focusing on the instrumental value of polysemy seems misguided. Neither liberal calls to salvage the liberal international orderFootnote 99 nor advocacy for striking a new, more inclusive deal for a governance framework with emerging powersFootnote 100 eventually seem like appropriate normative responses to the challenge of polysemy.

While our theoretical approach thus suggests a critical normative stance towards grand designs for international order and sympathises with pragmatic approaches such as ad hoc arrangements, it is clear that more research on the normative implications of norm ambiguity and norm polysemy is needed. Discussions about the ethical consequences and normative desirability of divergent meanings are strikingly absent from the existing IR literature. In contrast, a radically non-essentialist perspective recognises the normativity pervading the processes of meaning-making surrounding norms. It does not reduce differences of interpretation to questions of cognition but acknowledges them as constitutive characteristics of norm meaning itself.

Without foreclosing alternatives, we note a close affinity between our perspective on norm meaning and pluralist thinking in Political Theory. Seeing ambiguity as an inherent feature of norms makes it possible to regard norm polysemy not just as a structural feature of international society, but also as a fundamental expression of the normative diversity of the world's human communities. Human beings hold different values and different conceptions of what is good and just, which, in turn, influences their interpretation of norms. It seems intuitive to engage authors such as William Connolly, Chantal Mouffe, John Williams, and David Wong, who – despite their different subjects, intellectual backgrounds, and perspectives – share a commitment to normative disagreement and human diversity as the fundamental condition of society.Footnote 101 Based on this commitment, they explore how politics and institutions can preserve and promote the political, moral, and legal agency of human beings in their diversity instead of reducing them to mere functionaries of social structures. We would argue that understanding norm ambiguity is key in such an endeavour. Combining the radically non-essentialist understanding of norms with insights from pluralist theorising allows us to explore how global governance arrangements may harness the positive potential of human diversity by embracing ambiguity instead of attempting to ‘govern it away’ by fixing the meaning of norms. In this view, the value of international norms and governance frameworks would not be premised on the possibility of closing interpretive ‘gaps’ between essentially different actors (for example, through access to regular contestation).Footnote 102 The normative assessment of norm ambiguity thus shifts from one-sided considerations of its instrumental value (for example, its ability to induce cooperation or its distributive effects) to how governance mechanisms can channel the fundamental condition of norm ambiguity in a way that enables the enactment of difference and nurtures its positive value.Footnote 103

To be sure, there are ethical limits to tolerable interpretations of a norm's meaning. Even pluralists acknowledge that diversity needs limits in order to flourish. These limits arise, in the first place, from considerations about human dignity and harm, which underpin the general conditions under which actors can exercise their agency.Footnote 104 These ethical limits, as defined by the social field, render certain interpretations of a norm intolerable. As a consequence, interpretations such as the US's interpretations of the prohibition against torture noted earlier can be excluded from the range of normatively acceptable enactments of a norm's meaning, as they are not ethically appropriate – and legitimate – interpretations of a standard of appropriate behaviour.

Combining a consistently non-essentialist conception of norms with political theories of agonism may provide valuable insights to develop such normative reflections more systematically. Agonism subsumes a variety of normative perspectives that acknowledge difference as a basic condition of social life. However, in contrast to the dialogical understanding of agonism as it can be found in the contestation literature,Footnote 105 which ultimately seeks to escape from ambiguity and attempts to return to agreement through deliberation, our reconceptualisation of norm meanings suggests exploring forms of agonistic politics that sustain difference and are more accommodating of disagreement and conflict. Because problematising norm meaning ‘all the way down’ forefronts the politics of norm meanings, we propose to explore whether Mouffe's more radical work on agonistic politics provides a viable normative basis for global governance in a post-hegemonic world.Footnote 106 Previous work in IR, for example on the notion of ‘enlightened localism’,Footnote 107 or principles derived from non-Western traditions of thought like DaoismFootnote 108 and Confucianism,Footnote 109 may offer valuable building blocks for such an approach. Developing linkages between radically non-essentialist norms research and political theory will enable us to formulate a critique of contemporary global governance without having to rely on liberal, Western-centric standards.

This consciously normative and critical approach to norm meaning provides the ground for normative positions in the debate on the future of global governance that neither give in to liberal angst and its restorative reflex nor succumb to illusions about a new global normative consensus. These positions would instead ask which mechanisms of coping with norm polysemy are best suited to tolerate the elusiveness of deep moral consensus, how governance frameworks in areas such as climate, outer space or the cyber domain should be designed, and how existing governance arrangements can be reformed. Answering these questions will push us to think much more innovatively about the structure of, and forms of participation in, global governance institutions, leading us away from static notions of standard setting and compliance towards more flexible, open, and dynamic arrangements for the post-hegemonic era. A better understanding of the political dynamics of norm meaning is a precondition for such a project.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the helpful comments by the three anonymous reviewers.