Introduction

It is a political science truism: political authority drives public legitimacy expectations. According to the literature, international organisations (IOs) are no exception. As their member states delegate authority to IOs and pool authority among themselves in IOs to tackle pressing international problems, they gain authority to the extent that their related claim to make and implement binding decisions is publicly recognised.Footnote 1 Their increasing authority, in turn, drives public expectations about IO legitimacy. On the one hand, the public expects the polity of IOs to allow for participation, deliberation, and accountability (input legitimacy) and, on the other hand, that the policies of IOs effectively help in solving international problems (output legitimacy).Footnote 2

The IO legitimacy literature also claims that when IOs fail to meet these expectations, an authority–legitimacy gap opens up which subsequently drives their politicisation.Footnote 3 When IOs cannot live up to public expectations about their legitimacy – either input or output legitimacy – their policies as well as their polities will become contested by the public of their member states.Footnote 4 Due to their politicisation, the literature expects that IOs will seek to improve their legitimacy by, for instance, initiating reforms towards broader public participation, more public deliberation, and improved political accountability.Footnote 5 Yet this literature does not study who is actually held accountable by the public when IO policies fail to deliver effective solutions to international problems. This is unfortunate because it seems of utmost importance for their legitimacy whether policy failures are attributed to the IO and its member-state collective or to individual member states.Footnote 6 After all, only in the first instance is the IO delegitimised, whereas in the second instance the delegitimisation concerns individual member states’ behaviour.Footnote 7

The literature on blame avoidance in IOs, in turn, addresses question of whether responsibility for IO policy failures is attributed to the IO and its member-state collective – mostly delegitimising the IO – or to individual member states – delegitimising their behaviour. This literature assumes that in cases of IO policy failures, member states hardly ever become the main target of public responsibility attributions (PRA). As IO decision-making is typically shared by supranational and intergovernmental bodies and is thus complex, clarity of responsibility is lacking. Therefore, member states can employ IOs either as convenient scapegoats to shift blame,Footnote 8 or as smokescreens to diffuse blame.Footnote 9 Due to the complexity of IO decision-making, their members can always avoid public blame by hiding behind the IO.Footnote 10 According to this ‘complexity hypothesis’, PRA for IO policy failures will predominantly target the IO.Footnote 11 Indeed, PRA for the humanitarian crisis triggered by the United Nations (UN) oil embargo against Iraq in the 1990s did not target individual UN members such as the USA, but oscillated between the UN Secretary General, the UN Security Council, and the UN membership collective.Footnote 12 Similarly, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – and not individual member states – was held responsible for the economic recession that followed the tight fiscal policies it forced on many Asian countries in response to the 1997 Asian financial crisis.Footnote 13

However, while agreeing with the blame avoidance literature that IO policy failures will often trigger PRA that predominantly target IOs, thereby contributing to their delegitimisation, we note that sometimes PRA focus instead on individual member states. For instance, in contrast to the oil embargo against Iraq, an individual member state – namely Russia – was blamed for the UN Security Council’s inaction regarding the humanitarian crisis in Syria in the early 2010s.Footnote 14 Moreover, not the European Union (EU) but individual member states were held responsible for the failure of the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact, for instance in the case of Italy in 2018.Footnote 15 The question thus is: when do IOs become predominant PRA targets, and when are individual member states in the focus of PRA?

In this paper, we suggest that the type of policy failure provides an answer. We hold that the type of IO policy failure shapes the clarity of responsibility of those political actors that were de jure or de facto instrumental for the policy failures. In cases of performance failures (i.e. when IO policies are not appropriate), we expect clarity of responsibility to be lacking, thus allowing states to diffuse blame or to shift blame onto IOs. By contrast, in cases of failures to act and failures to comply (i.e. when IOs are unable to enact policies or their policies are disregarded), we expect individual member states’ responsibility to be rather clear so that they will draw the bulk of PRA. While this hypothesis may not appear surprising, it is also not as obvious as it seems at first glance. After all, it conflicts with the ‘complexity hypothesis’ dominant in the literature, which expects that, independent of the type of policy failure, the bulk of PRA will always target the IO.

The ambition of this paper is to develop this ‘failure hypothesis’ theoretically and to illustrate its empirical plausibility. In doing so, we do not only challenge the ‘complexity hypothesis’ common in the literature on blame avoidance in IOs but also go beyond this literature, as we do not focus on the blame strategies individual actors – mostly states – employ in cases of IO policy failuresFootnote 16 but on the PRA that become, in cases of IO policy failures, predominant in the public domain. We study the PRA that ‘stick’ in the public, because it can be assumed that the PRA that are most common are also the ones that have the strongest impact on the legitimacy of the targeted actors.Footnote 17

The paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we spell out how different types of failures translate into PRA that mainly target either the IO and its member-state collective, or individual member states. In the third section, we discuss our research design for the assessment of the ‘failure hypothesis’. We focus on EU policy failures since, as an extremely complex IO, PRA targeting specific member states are particularly unlikely in the EU, which thus constitutes a ‘crucial case’ for our theory.Footnote 18 We engage in two pairwise comparisons of EU policy failures: first, we compare PRA for the EU failure to act in the Libyan crisis in 2011 with PRA for the performance failure of the EU sanctions against the Russian aggression in Ukraine in 2014. Second, we compare PRA for the EU’s failure to perform regarding the Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) aimed at implementing the Kyoto Agreement with PRA for the failure of National Determined Contribution (NDC) plans to comply with the ambitious EU climate goals under the Paris Agreement. A content analysis of newspaper coverage of the EU foreign policy case pair (the fourth section) as well as the EU environmental policy case-pair (the fifth section) lends support to our ‘failure hypothesis’. The final section concludes by summarising the paper’s results and discussing their broader implications for the accountability and performance of IOs.

Theory: Clarity of responsibility for IO policy failures

Who is held publicly responsible for IO policy failures, i.e. for IO policies that disappoint public problem-solving expectations? As indicated above, the IO blame avoidance literature generally assumes that in cases of IO policy failures, the bulk of PRA will always target the IO, thereby contributing to their delegitimisation. It argues that due to the complexities of IO decision-making, states can always – and thus independent of their true responsibilities, i.e. their de jure or de facto role in policymaking – avoid becoming the main target of PRA. Seeking to maintain their own legitimacy, they will contribute to the delegitimisation of IOs.

We argue, by contrast, that even in IOs with complex decision-making procedures, clarity of responsibility is not always lacking.Footnote 19 After all, it is in the public sphere that political actors exchange responsibility attributions to shape public perception about who is to blame for IO policy failures.Footnote 20 In the public, they try to avoid blame for themselves and to generate blame for their political opponents. However, while political actors do this mostly in an opportunistic fashion, their PRA are also critically assessed for their plausibility. In the public sphere, their PRA not only compete with other political actors’ conflicting PRA but they are also critically evaluated by other actors, including civil society actors, business associations, experts, and journalists. The public sphere thus functions as a marketplace where competing PRA are vetted for their plausibility.Footnote 21

In cases of IO policy failures, this public plausibility assessment improves clarity of responsibility.Footnote 22 Due to the public plausibility assessment of political actors’ PRA, citizens will learn about true responsibilities for IO policy failures, which in turn will constrain the PRA political actors can assign to avoid blame for themselves or to generate blame for others. Their PRA must not deviate (too far) from true responsibilities as this would harm, among citizens, their reputation as trustworthy political actors.Footnote 23 Therefore, they have an incentive to keep their PRA plausible enough to maintain the ‘illusion of objectivity’.Footnote 24

We suggest that whether this incentive to keep their PRA plausible is strong enough to prevent political actors from successfully obscuring their ‘true’ responsibilities depends on the type of policy failure. Our ‘failure hypothesis’ thus claims that the type of IO policy failure shapes whether PRA will predominantly target the IO along with its supranational and intergovernmental bodies; or whether PRA will mainly target individual member states (MS). We distinguish three types of IO policy failures: failures to act, failures to perform, and failures to comply. Figure 1 summarises the expectations of our failure hypothesis.

Figure 1. IO policy failures and public responsibility attributions.

Failures to act

In cases of failures to act, we expect individual member states, rather than the IO, to become the main PRA target, thus delegitimising the respective member states’ behaviour. Failures to act imply that IOs are unable to enact policies to address the problem they are expected to tackle.Footnote 25 Whereas failures to perform come with poor IO policies, failures to act imply that the IO is unable to make any relevant policy that stands a chance of solving the problem. The EU’s inability to act through its Common Foreign and Security Policy to tackle crises such the ethnic cleansing in Kosovo, the Iraq war, or the humanitarian disaster in Darfur may serve as examples.Footnote 26 The UN Security Council’s inertia regarding the humanitarian crisis in Syria in the early 2010s also constitutes a failure to act.Footnote 27

In cases of IO failures to act, we generally expect blocking actors to stick out of the IO collective and to become the main target of PRA. After all, blocking actors could have allowed the IO to act. In principle, this could be supranational IO bodies as well as individual member states in intergovernmental IO bodies. However, as supranational IO bodies typically have an institutional self-interest to make decisions, it is hardly ever they that block IO decisions, as this would also harm their legitimacy. Moreover, supranational IO bodies rarely have the institutional ability to block decisions single-handedly. Therefore, they are hardly ever responsible for IO failures to act. If intergovernmental IO bodies cannot act to address the problems they are meant to tackle, it is typically individual member states (or coalitions of member states) that block decisions. They block IO decisions when they fear that decisions might harm their national interests. Moreover, they also have the institutional ability to block IO decisions. As their member states typically are sovereign and thus retain ultimate authority, IOs can only make decisions with their members’ agreement. Therefore, it is individual member states rather than the IO that are usually responsible when IO decision-making is not just deficient – as in the case of failures to perform – but blocked – as in the case of failures to act.

In cases of IO failures to act, member states cannot simply avoid PRA by hiding behind the IO. After all, blocking member states’ responsibility for IO failures to act is typically clear. Irrespective of the particular decision-making procedures, the blocking members are comparably easy to detect. While IO bodies might shy away from blaming blocking member states,Footnote 28 those member states that were in favour of an IO decision will almost always render this information public. To avoid being held publicly responsible for the IO failure to act, they will name the blocking member states, thereby directing PRA towards them. Other political and social actors, such as opposition parties, journalists, and experts, will also point out the respective member state’s de facto or de jure responsibilities for the failure to act. In the course of the public plausibility assessment, the responsibility of blocking member states thus will become clear. In cases of failures to act, they will therefore become the predominant target of blame.

Failures to perform

In cases of IO performance failures, we agree, by contrast, with the literature that PRA will predominantly target the IO thereby contributing to their delegitimisation.Footnote 29 Failures to perform arise when IOs draw on their decision-making authority to enact policies that fail to solve the problem they were meant to tackle. In cases of failures to perform, IOs disappoint public expectations, because in terms of problem-solving they make poor policies.Footnote 30 For example, EU border control policies implemented by Frontex constitute a performance failure as they failed to prevent (or even contributed to) the death of thousands of migrants in the Mediterranean.Footnote 31 Similarly, the UN oil embargo against Iraq in the 1990s, which triggered a humanitarian crisis, amounts to a performance failure.Footnote 32

In cases of performance failures, we generally expect the actor carrying decision-making authority to become the main PRA target and thus to be publicly delegitimised. After all, decision-makers could have enacted better policies. However, as IO decision-making is often shared by supranational and intergovernmental IO bodies which jointly make decisions in a multi-step process, singling out those decision-makers that actually pushed the respective policy becomes a complex undertaking. This provides member state governments the opportunity to avoid blame for performance failures.Footnote 33 To maintain their own legitimacy, they can diffuse blame by highlighting that complex decision-making in IOs always requires compromises. They can shift blame onto the IO by highlighting that decisions have been jointly made with other member states in intergovernmental IO bodies or were pushed by supranational IO bodies. And they can diffuse blame by attributing responsibility to the IO.

In either case, member states can have it their own way, because IO bodies are unlikely to publicly correct their blame avoidance attempts. They will not highlight that the very same states that are now denying responsibility had agreed on these policies before. After all, IOs are agents of their member-state principals who granted them authority in the first place and are usually also able to rescind authority from them. Thus, depending on their member states’ continuing support, IOs will rather quietly accept responsibility than publicly shift responsibility back to their members. Even after the public plausibility assessment, it will therefore remain difficult to disentangle which specific actors carried how much de facto or de jure responsibility during the decision-making procedures that shaped the policy that failed to perform. In line with the ‘complexity hypothesis’, we thus expect that at least in cases of IO performance failures, PRA will predominantly target the IO thereby contributing to their delegitimisation.

Failures to comply

For IO failures to comply, we expect, by contrast, individual member states rather than the IO to become the main PRA target. Failures to comply arise when IO policies are disregarded. As opposed to IO failures to act, the IO has already enacted a relevant policy, and as opposed to failures to perform, the policy appears to be adequate, but compliance with this policy is deficient. The IO disappoints public expectations because it proves unable to ensure compliance. The US intervention in Iraq without UN Security Council authorisation constitutes a compliance failure, as does Italy’s disregard of the EU Stability and Growth Pact.Footnote 34

In cases of failures to comply, we generally expect the non-compliant actor to stick out from the IO collective and to become the main PRA target. In principle, the non-compliant actors could be individual IO member states or individual IO bodies. In practice, however, it is mostly member states that disregard IO policies. IO bodies are rarely the addressees of IO policies and if they are, they usually comply with these policies. After all, it is in their institutional self-interest to comply with their own policies.Footnote 35 By contrast, the member states are usually the addressees of IO policies, and they often face incentives to disregard them. Moreover, as states typically retain operative authority, IOs also need to rely on their member states for the implementation of policies addressing non-state actors. Therefore, it is typically the member states’ responsibility to ensure compliance of those non-state actors that are subject to their authority. In any case, individual member states tend to be the actors responsible for compliance failures.

Yet, as opposed to performance failures and just as with failures to act, in cases of compliance failures member states cannot avoid PRA by hiding behind IOs and thus contributing to their delegitimisation. While in cases of failures to perform the lack of clarity of responsibility due to IOs’ complex decision-making enables member states to avoid PRA by pointing responsibility towards the IO, non-compliant member states’ responsibility for IO failures to comply is usually clear. Once the public plausibility assessment sets in, the non-compliant member states will become the main PRA target. After all, to avoid being targeted by PRA themselves or sanction the member state sheering off a common policy, complying member states will blame the non-compliant member state, thereby pointing public responsibility attributions towards the said member state. Moreover, some IO bodies face particular incentives – and sometimes are even mandated – to publicly call out non-compliant member states. Additionally, other political and social actors such as opposition parties or journalists will also highlight the respective member state’s de facto or de jure responsibilities for the failure to comply. Overall, we expect that in cases of failures to comply, PRA will predominantly target non-complying member states individually rather than the IO in general.

Research design: Assessing PRA for EU policy failures

We evaluate the plausibility of our ‘failure hypothesis’ by studying the attribution of responsibility in four cases of EU policy failures. We opted to focus on the EU rather than other IOs because it constitutes a ‘crucial case’Footnote 36 for our ‘failure hypothesis’. The EU is an extremely complex IO, maybe even the most complex one. Authority in the EU varies from issue to issue and is often shared between intergovernmental and supranational bodies.Footnote 37 Hence, the complexity hypothesis should hold here if anywhere, because it is particularly plausible that citizens should have difficulties in attributing responsibility correctly in the EU.Footnote 38 Member states should thus have a particularly easy time of hiding behind the EU. If we nevertheless observe in an IO as complex as the EU that PRA for failures to act and failures to comply predominantly target specific member states, we can be confident that our ‘failure hypothesis’ also holds in less complex IOs.

We study PRA for two pairs of similar EU policy failures. The first case pair consists of two foreign policy failures that allow us to compare PRA with regard to an EU failure to act and an EU failure to perform:

• The failure to act in the Libya case: When in 2011 Libyan authoritarian leader Muammar Gaddafi employed military force not only against opposition groups that rebelled against his reign but also against the wider population, the EU failed to agree on a substantive – perhaps even military – intervention.Footnote 39 The EU’s inaction disappointed public expectations that it would be able and willing to protect the Libyan population. In fact, the EU’s non-adoption of a common policy – its failure to act – was heavily criticised by the European public.Footnote 40

• The failure to perform in the Russia case: When in 2014 Russia illegally annexed Crimea from Ukraine and supported pro-Russian forces to destabilise Eastern Ukraine, the EU reacted by levying a multiple-step sanctions regime.Footnote 41 However, the EU’s sanctions regime clearly disappointed public expectations. On the one hand, it was criticised for being too soft to force Russia to withdraw from Ukraine and, on the other hand, it was criticised for being hard to swallow for the European economy.Footnote 42

The second case pair consists of two environmental policy failures, which help us to compare PRA with regard to an EU performance failure and an EU compliance failure:

• The failure to perform in the ETS case: The EU introduced a CO2 emission trading scheme (ETS) in 2003 as its most important ‘cap-and-trade’ measure to meet the CO2 reduction targets it agreed in the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. The performance of the ETS was widely regarded as a disappointment by the public as it failed to effectively limit CO2 emissions.

• The failure to comply in the NDC case: To achieve the objectives of the Paris Agreement to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels, the EU requires its members to put in place ambitious National Determined Contribution (NDC) plans. However, some member state plans fell short of the joint EU climate policy.

We selected the two pairs of cases according to the logic of a most-similar-case-design.Footnote 43 As indicated above, within each case pair the cases differ with regard to the type of IO policy failure, but they are similar with regard to a number of potentially confounding variables, thus allowing us to isolate the effect of the failure type (independent variable) on the PRA target (dependent variable) while controlling for the confounding variables. First of all, the cases are similar to the extent that they involve the same IO: the EU. Most importantly, by looking at one and the same IO, we control for its overall complexity. As IO complexity is considered key for PRA by the IO blame avoidance literature, comparing failures of IOs with different levels of complexity would distort our analysis.Footnote 44 Moreover, by studying four cases in the EU, we also control for the general level of legitimacy the IO enjoys. After all, as the general level of legitimacy is found by the respective literature to vary across IOs, looking at different IOs would disturb the comparison.Footnote 45

We also control for potentially confounding factors within the two case pairs. First of all, cases of the same case pair belong not only to the same policy field but even address similar issues: both EU foreign policy cases concern illegitimate military operations of foreign countries the EU had to cope with in its near neighbourhood; and both EU environmental policy cases relate to EU efforts to bring its members’ carbon emissions into conformity with international agreements. We thus control for a number of confounders, such as politicisation, that the literature found to vary not only across IOs but also across issues.Footnote 46

Furthermore, the decision-making procedures are similar within each case pair. Both EU foreign policy cases were subject to the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), which limits decision-making authority to the Council.Footnote 47 In the two EU environmental policy cases, following a proposal by the European Commission, the Council and the European Parliament shared policymaking authority.Footnote 48 We thereby control not only for the legitimacy and complexity of these procedures, but also for the authority the IO may wield with regard to the respective policies.Footnote 49 After all, the literature on IO blame avoidance also indicates that authority structures shape PRA.Footnote 50

To assess the plausibility of the ‘failure hypothesis’, we study the blame attributions for the four EU policy failures in the coverage of the European quality press. We focus on the media instead of drawing on surveys because we are interested in the blame attributions that become predominant in the public sphere, rather than blame attributions citizens accept when asked in private and thus in isolation from each other. We focus on the quality press rather than the tabloid press, television, or social media because it is still considered to function as leading media and is thus a good proxy for capturing the public sphere in European countries.Footnote 51 In the quality press, we can assess PRA not only from journalists, but also from public officials, party leaders, civil society actors, experts, and business leaders, both national and international.Footnote 52

We examined the reporting by eight quality European newspapers from four countries: Süddeutsche Zeitung and Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung from Germany, Le Monde and Le Figaro from France, The Guardian and The Times from the United Kingdom (UK), and Der Standard and Die Presse from Austria. While perhaps not fully representative of the European public as a whole, these four countries differ in important dimensions: three countries are big, one is small; two have a past of military activism, two are rather civil powers; and two are rather Eurosceptic and two pro-European countries. We therefore assume that this selection of newspapers – not countries – allows us to approximate PRA for the two case pairs in the European press.

To identify in the selected newspapers PRA for the four EU policy disappointments, we conducted a keyword search in the digital newspaper archive Factiva, using the same case-specific search string across all newspapers.Footnote 53 In the EU foreign policy case pair, we started our analysis at the point in time where the respective failures were publicly discussed for the first time, i.e. 15 February 2011, in the case of Libya and 17 March 2014, in the case of Russia. We then analysed the coverage of the two EU foreign policy failures for a period of one year. In the EU environmental policy case pair, the beginning of our analysis coincides in the ETS case with the start of the commitment period on 1 January 2008,Footnote 54 and in the NDC case with the EU’s ratification of the agreement on 5 October 2016. We analysed the coverage of the two EU environmental policy failures until 1 June 2020. Through the digital keyword search, we identified overall 1,614 articles, which we then reviewed manually to sort out duplicates as well as articles that did not address the respective policy failures. In the resulting sample of 397 relevant articles, we then coded all statements that amounted to PRA.Footnote 55

PRA were identified based on three criteria, each of which was considered necessary, and which are seen only in combination to be sufficient:Footnote 56 (1) There is a clearly stated PRA sender, i.e. an individual or corporate actor that attributes political responsibility for an EU failure; (2) there is a PRA object, i.e. a clearly stated policy failure for which political responsibility is attributed; (3) and there is a PRA target, i.e. a clearly named political actor to whom political responsibility is attributed. We identified 574 statements that amount to PRA: 100 in the Libya case, 197 in the Russia case, 147 in the ETS case, and 130 in the NDC case. We coded for each statement whether responsibility was attributed to the EU and the collective of its member states or to one (or several) individual member states:

• PRA to the EU in general: We coded PRA statements targeting the EU when they refer to the EU, its supranational and intergovernmental bodies, or their representatives (such as the President of the Commission or the Council).

• PRA to individual member states: We coded PRA statements targeting individual member states when they refer to a specific member state, including its governing institutions and their representatives (such as head of government or minister).

To evaluate our theoretical expectations, we test the following two propositions:

• Relative shares across cases: In cases of failures to act and failures to comply, the share of PRA targeting individual member states is, all else being equal, higher than in cases of failures to perform.

• Absolute shares within cases: In cases of failures to act and failures to comply, PRA predominantly target individual member states, whereas in cases of failures to perform, the IO in general becomes the predominant target.

Public responsibility attributions for EU foreign policy failures

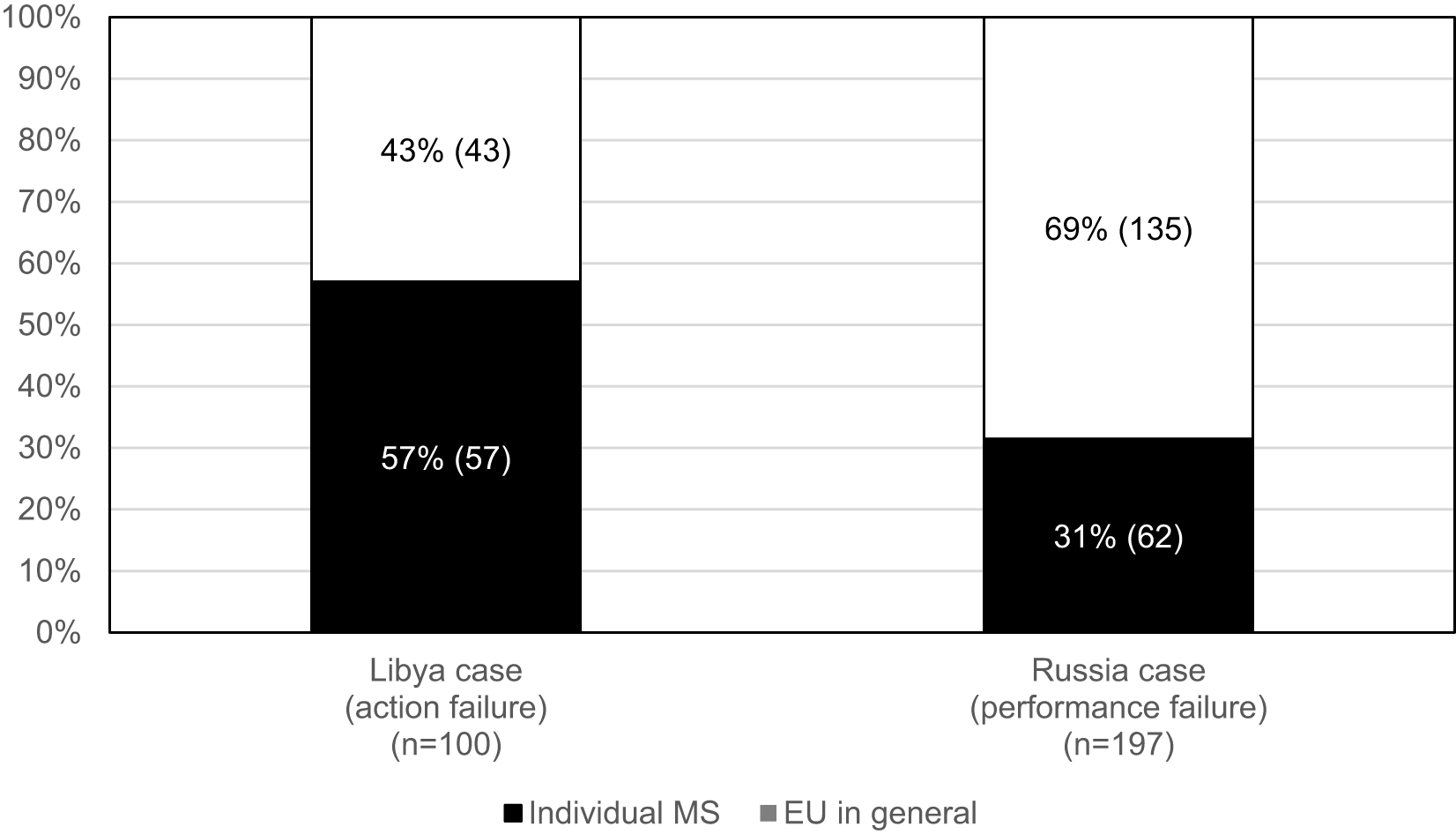

According to our proposition about relative shares, in cases of failures to act (as in the Libya case) the share of PRA targeting individual member states is, all else being equal, higher than in cases of failures to perform (as in the Russia case). The comparison of the shares of PRA across the Libya and Russia cases lends support to this proposition (see Figure 2). In the Libya case, the share of PRA attributing responsibility to individual member states is higher (57 per cent) than in the Russia case (31 per cent). PRA shares do not only differ substantively across the two cases (26 percentage points), but the difference is also significant. According to a chi-square test, we can reject the null hypothesis of a random distribution on the 99 per cent confidence level (see Appendix, Table A.5).

Figure 2. PRA targets in the EU foreign policy case pair.

Furthermore, according to our proposition about absolute shares, we expect PRA to be predominantly attributed to the member states in the Libya case (as a failure to act) and to the EU in the Russia case (as a failure to perform). The PRA in both cases lend support to this expectation not only in the aggregate of the media coverage across the four countries, but also in three out of four individual countries, with the UK being the only exception (see Appendix, Table A.12).

The bulk of PRA in the Libya case targeted the member states. While a majority of 57 out of 100 statements was directed at EU member states (57 per cent), only a minority of 43 statements was targeting the EU or the member states as a collective (43 per cent) (see Figure 2). Moreover, in line with our hypothesis, a good portion of PRA that targeted EU member states was directed at Germany, which was seen as the EU member that prevented the EU from engaging in joint action. For instance, the UK Conservative Party claimed ‘that the German abstention meant a clear failure of EU foreign policy’.Footnote 57 In a similar vein, a report from the Austrian Die Presse stated:

The abstention of Germany in the Libya Resolution in the UN Security Council … seemed to be the end of a common foreign policy for a lot of EU diplomats. In addition, there was the refusal of Berlin to contribute to joint military missions. The common foreign policy, as already feared, becomes the scourge of German domestic politics.Footnote 58

At the same time, only a minority of PRA targeted the EU or the member states as a collective. One example stems from the German Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, in whose reporting the EU failure to act was heavily criticised:

When it came to the acid test in Libya, the Union presented itself as disunited as in 2003 before the war in Iraq and similarly unable to act as in Yugoslavia 20 years ago. … Europe does not speak with one voice, and it doesn’t act – even though again, everything happens in front of its doorstep.Footnote 59

By contrast, in the Russia case, PRA were predominantly targeted at the EU or member states as a collective. A majority of 135 out of 197 statements attributes responsibility to either the EU or the collective member states (69 per cent), whereas a minority of 62 statements was directed at individual member states (31 per cent) (see Figure 2). For instance, the British Times reports that then Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras ‘criticized sanctions linked to the Ukraine conflict’, claiming that ‘the EU … was “shooting itself in the foot”’.Footnote 60 Similarly, Peter Gauweiler, vice-president of the governing Christian Social Union (CSU), stated that, by levying sanctions, ‘Brussels brought us into an escalation of threats’.Footnote 61

Only a minority of PRA in the Russia case targets specific EU member states. But even these statements shy away from naming these members and their leaders. For instance, President of the European Council Donald Tusk reportedly accused ‘certain EU leaders of preferring “appeasement” of Russia in the Ukraine conflict and of “naiveté or hypocrisy” in seeking to give Vladimir Putin the benefit of the doubt’.Footnote 62

Public responsibility attributions for EU environmental policy failures

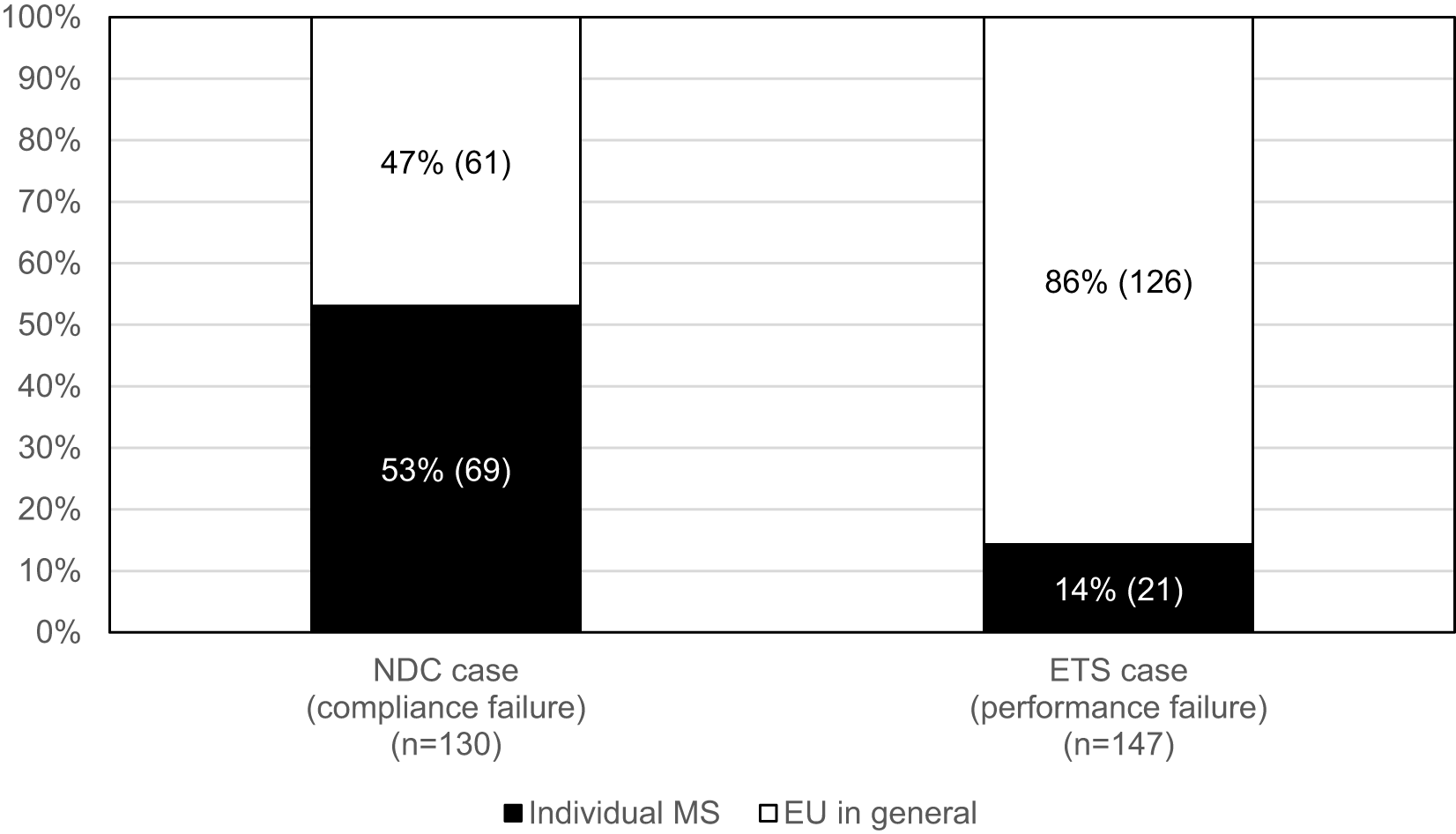

According to our proposition about relative shares, in cases of failures to comply (as in the NDC case) the share of PRA targeting individual member states is, all else being equal, higher than in cases of failures to perform (as in the ETS case). The comparison of the shares of PRA across the NDC and ETS cases lends support to this proposition (see Figure 2). In the NDC case, the share of PRA to individual member states is higher (53 per cent) than in the ETS case (14 per cent). Again, the difference (of 39 percentage points) across cases is not only substantial but also significant. A chi-square test shows that the null hypothesis of a random distribution can be rejected on the 99 per cent confidence level (see Appendix, Table A.6).

Moreover, according to our proposition about absolute shares, we expect PRA to predominantly target the EU and the collective of its member states in the ETS case (as a performance failure), and to focus mainly on individual member states in the NDC case (as a failure to comply). PRA in both cases conforms to this expectation not only in the aggregate of the media coverage across the four countries selected for the analysis, but also in each of these countries individually (see Appendix A.11–14).

In the ETS case, the bulk of PRA is directed at the EU and the collective of its members: out of 147 PRA statements, 123 (86 per cent) target the EU or the member-state collective while a minority of 21 statements (14 per cent) targets individual member states (see Figure 3). For instance, the responsibility for the failure that ‘the market was flooded with certificates’ is assigned to the EU in general as ‘the EU allocated the certificates way too generously to the 12,000 companies participating in the trading scheme’.Footnote 63 Similarly, the ETS is called ‘embarrassing for the EU’.Footnote 64 Even more bluntly, climate activists blamed the EU for creating a ‘letter of indulgences for environmental sinners’ with the ETS.Footnote 65 Other PRA statements direct responsibility to the collective of the EU’s member states. For instance, the trading system’s continued failure to perform is attributed to ‘the strength of industrial lobbies and the weakness of government resolve’, rendering it ‘completely useless’.Footnote 66

Figure 3. PRA targets in the EU environmental policy case pair.

Only a minority of PRA statements assigns responsibility for the EU’s failure to perform in the ETS case to individual member states. If so, the member states were mostly blamed for failing to unilaterally adopt stricter measures (a failure to act) or falling short of the agreed-upon carbon reductions (a failure to comply). For instance, Ireland was blamed by an NGO for its failure to live up to its emission targets: ‘Enda Kenny’s two governments have literally made no plan to meet our 2020 EU targets which the minister admitted we will overshoot this year or next’ while ‘emissions had risen by 4 per cent last year’.Footnote 67

By contrast, in the NDC case, a majority of 69 of 130 PRA statements was directed at individual member states (53 per cent), while a minority of 61 statements was assigned responsibility to the EU or the member-state collective (47 per cent) (see Figure 3). Individual member states were heavily criticised for not complying with the climate and emission targets set under the EU regulation adhering to the Paris Agreement. For example, Austria was blamed for falling short of reaching its 2030 commitments: ‘Austria is strikingly missing the 2030 EU climate targets. … Until 2030, Austria has to reduce its emissions by 36% under EU regulation in comparison to 2005. As of now, all national energy and climate commitments only account for a reduction of 27%.’Footnote 68 In the same vein, the ‘little action’ by Germany was also fiercely criticised: ‘Although the Germans talk about environmental protection more than almost anyone else in the world, they release more carbon dioxide in relation to the size of the country than almost anyone else.’Footnote 69 Also then-EU member the UK was blamed for its failure to reach its national climate goals. Barry Gardiner, the shadow international trade and climate spokesman (Labour), claimed:

2018 is the year when countries have been asked by the UN to ratchet up their commitments on climate change. Instead our government is actually proposing to count emissions savings made from as far back as 2010 towards fulfilling their obligations in the next decade from 2021–2030. This sneaky, behind-the-scenes amendment indicates a government that likes to pretend it is a global leader but will not take the strong policy action needed to deliver the necessary change.Footnote 70

Similarly, the Irish government was blamed by a member of the Green Party for its measures being ‘nowhere near good enough’Footnote 71 to meet its climate objectives. Finally, Poland, Estonia, Hungary, and the Czech Republic were respectively condemned as ‘irresponsible’ by environmental activists.Footnote 72

A minority of PRA statements was assigned either to the EU or the collective of its member states. For example, EU member states were collectively made responsible for failing to enforce the EU’s climate goals within the Paris Agreement: ‘The failure up to now of the 28 member states to commit to a goal of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, let alone anything more ambitious, highlights the danger of history repeating itself.’Footnote 73 MEP Ska Keller from the Green Party also blamed the member states for their unwillingness to adopt stricter climate measures calling it a ‘disgrace’ that even though ‘many people voted for more climate protection within the European elections … it is more important to protect industry interest for the EU member states’.Footnote 74

Conclusion

The two pairwise comparisons corroborate our ‘failure hypothesis’. In the EU foreign policy case pair, PRA for the EU’s failed intervention in Libya (failure to act) targeted individual EU member states, while it was predominantly directed at the EU as well as the collective of its member states in the case of the Russia sanctions (failure to perform). In the EU environmental policy case pair, the majority of PRA was directed at the EU and the collective of its member states in the ETS case (failure to perform), whereas individual EU member states were held responsible most of the time in the NDC case (failure to comply).

Our ‘failure hypothesis’ also holds when moving from the above comparison of four cases of EU policy failures to the level of individual PRA statements. The analysis of all the 574 PRA statements that we coded for the four cases of EU policy failures indicates that PRA statements that hint at performance failures tend to target the EU, whereas PRA statements hinting at either failures to act or failures to comply tend to target individual member states. The null hypothesis of a random distribution of PRA targets can be, according to the chi-square test, rejected on the 99 per cent confidence level (see Appendix, Table A.16 and A.17).

While the comparison of PRA in the four cases as well as the analysis of all PRA statements in these cases clearly increases our confidence in the ‘failure hypothesis’, two caveats are in order: first, while we found the expected PRA patterns in three of the four countries, the null hypothesis could not be rejected for the British sub-sample in both case pairs. One reason could be that expectations towards the EU were generally less pronounced in the UK than in Germany, France, and Austria.

Second, whereas the employed most-similar-case-design allows us to be confident with regard to the internal validity of our results, it also raises the issue of their external validity. For instance, we cannot be sure that our arguments apply to other issue areas or IOs. However, the fact that our ‘failure hypothesis’ was supported for EU policy failures in issue areas as different as foreign policy and environmental policy increases our confidence in the external validity of our findings. Moreover and most importantly, due to its overall complexity the EU generally constitutes a ‘crucial case’ for our argument. As we find that in cases of failures to act and failures to comply member states cannot hide behind the EU, we can assume this to be true as well for IOs that are less complex than the EU. At least with regard to these failures, it is hard to see why the failure hypothesis should not travel to IOs that are less complex than the EU where it should be even more difficult for states to hide behind the IO. With regard to performance failures, though, our failure hypothesis might not travel as easily from the EU to less complex IOs. It could actually be that it requires the complexity of the EU for states to be able to avoid becoming the main target of PRA. In cases of performance failures, an IO might thus only become the predominant blame target when it is also complex, whereas in non-complex IOs the member states may become the main PRA target.Footnote 75 With regard to performance failures, further research is thus needed to study the interaction with the level of IO complexity and assess whether it holds also that IOs that are less complex than the EU become, in cases of performance failures, the main PRA target.

From a normative perspective, our theory’s implications appear positive, at least at first glance. While some studies argue that the number of veto players in IOs and their increasing preference heterogeneity will lead to IO deadlock,Footnote 76 our hypothesis suggests that states that block joint IO policies to address global problems, and thus generate IO failures to act, will become the target of PRA and be held to account – at least when they act as isolated veto players.Footnote 77 This points to a disincentive for states to use their veto power too frequently – a disincentive the literature on IO deadlocks has overlooked so far. Similarly, while some studies argue that the lack of centralised IO enforcement renders IO policies ineffective,Footnote 78 our hypothesis suggests that states that disregard IO policies, and thus generate IO compliance failures, will become the target of PRA and held to account.Footnote 79 This points to a disincentive for states to violate their commitments in IOs – a disincentive the literature on compliance has always assumed but rarely analysed empirically.

At a second glance, however, the normative implications of our results are more negative. To the extent that member states cannot agree on effective IO policies, they face strong incentives to agree at least on symbolic policies which are then prone to performance failures. After all, member states prefer IO performance failures (resulting from symbolic policies) over IO action failures (which arise if they cannot agree on any policy) or IO compliance failures (which arise if they disregard agreed policies). Symbolic policies allow member states to avoid failures to act (as they are easier to agree on), and they also help states to avoid failures to comply (as they are easier to adhere to). Thus, at least in the short run, IO member states will prefer symbolic IO policies.Footnote 80 In the long run, however, symbolic policies that fail to address pressing global problems are likely to undermine the legitimacy of IOs and thus the very IO authority on which their ability to absorb public responsibility rests.

To constrain member states’ opportunities to avoid blame in IOs, simplicity is key. While policymaking in many IOs is shared among supranational and governmental actors, their responsibilities should be separated to ensure that specific IO bodies or even actors can be held accountable by the public. Increasing the clarity of responsibility in IOs thus promises to improve not only their accountability but also their performance and thus both their input as well as their output legitimacy.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210524000330.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the three anonymous reviewers, the editors, as well as the participants of the Global Politics Research Colloquium at LMU Munich. We are specifically grateful to Marius Mehrl, Carolyn Moser, and Sebastian Schindler for their very helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. We also would like to thank Andrea Johanson and Simon Zemp for their invaluable support in identifying and coding public blame attributions. Our research was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (project number 391007015). It immensely benefited from our joint work with Lisa Kriegmair and Berthold Rittberger in this project on European Blame Games.