Introduction

The media is essential to any discussion about conflict and peace. It is not merely a medium, but also a tool political actors employ in order to develop, refine, and promote their own agendas and strategies. It is also an independent actor that creates pressure for action on issues it deems necessary or justified. Since the ‘CNN effect’ was first coined in 1991 in the wake of the US intervention during the Kurdish crisis in Northern Iraq,Footnote 1 the term has grasped a range of the novelties brought about by live 24-hour news reporting from conflict scenes, and its catchiness quickly made it a popular concept both in scholarly and policy circles. Rapid changes in the global media environment, however, and the proliferation of conflict actors employing the media for strategic gain, require a new conceptual and theoretical approach to understanding media-conflict interactions.

While groundbreaking technological innovations were commonplace throughout the twentieth century, the exponential growth in digital communications technology has created an unprecedented proliferation of media sources, and new means of media penetration into our lives. This trend is accelerating in the twenty-first century, and will challenge both our perceptions of, and the actual influences between, information and political action. Although new communications technologies are often claimed to make distant areas more accessible, their use also highlights the differences between various conflict locations, old and new actors, and translation of local events through different levels of local, national, international, and global media. Placing this trend in the context of existing media platforms, and different geographical and cultural patterns of media use, requires understanding how evolving media environments – including both traditional news media and internet-based communication platforms – have influenced conflict dynamics.

This study offers a path towards that aim, by combining two theoretical contributions from the fields of media and communication and postcolonial studies. In part, our approach draws upon Roger Mac Ginty’s concept of hybridity,Footnote 2 in order to show how different levels of media can be fluid, and their interactions likewise influence the outcome of both top-down and bottom-up enterprises. Our contribution also builds on Eytan Gilboa’s approach to understanding the multilevel interactions between local, national, regional, international, and global media.Footnote 3 To paraphrase from Gretchen Helmke and Steven Levitsky,Footnote 4 our goal is to broaden the scope of media analysis by adding multilevel interactions. In particular, we stress the need to reintroduce the ‘local’ level in current media studies, both because media reporting on conflicts eventually affect the local level conflict and political dynamics, and because of the discrepancies that often exist between the level where the conflicts occur and how they are narrated throughout different media layers. These innovations should enable scholars from varied disciplines to gain a better understanding of the complex relationship between media and conflict, which should result in both better theory and research which is sensitive to the permeability, interactions and mutual influences between different levels of media that affect conflict dynamics and conflict responses.

This study starts by first outlining the existing scholarship on media and conflict, including the CNN literature, and notes, in particular, its Western-centric focus and inattention to the influences of local reporting on local conflict dynamics and external responses to them. We then highlight two areas that must be accounted for in research today: (1) the multiplication and fragmentation of media outlets and their subsequent impact upon twenty-first-century newsgathering technology; and (2) the role of local media such as outlets based in conflict districts or regions, or national media that cover conflicts in their immediate periphery. The study then introduces the concepts of hybridity and multilevel interactions and discusses their utility for understanding better contemporary media-conflict dynamics. Building upon this conceptual basis, we conclude by setting out five new research streams that can enable researchers to harness the interaction effects from the local to the global and help to better understand contemporary media-conflict interactions.

Media and conflict from the Cold War to today

The literature on the CNN effect is only one element of a broader body of work on media-conflict interactions. The largest body is the substantial and longstanding literature on the relationship between media and war,Footnote 5 most of which has highlighted the propensity for news media to mobilise in support of government war aims and focuses upon Western (mainly US) initiated conflicts, or so-called limited wars of national interest.Footnote 6 In this scenario, patterns of media deference to political elites, elite propaganda campaigns, as well as other ideological imperatives mean that media frequently serve as a critical tool in exacerbating or even instigating conflict. The CNN effect literature, at least initially, presented an alternative reading of the relationship between media and conflict, and focused on the emerging 24-hour all news global providers (then dominated by CNN) as well as traditional broadcast media (TV news and broadsheet newspapers), to better understand how real-time reporting facilitated by portable satellite and electronic newsgathering equipment influenced the making of news, and their effects on policymaking.Footnote 7 Most of the CNN effect scholarship focused on the influence of US domestic media and CNN on US-led military interventions in humanitarian crises such as the 1991 Kurdish crisis in Northern Iraq, Somalia in 1991–2, Bosnia in 1994–5 and Kosovo in 1999. As such, this analysis conceptualised media as a largely domestic-level influence over government decisions for or against intervention into humanitarian crises in regions with relatively low inherent strategic value, so-called ‘other people’s wars’. Smaller bodies of literature have examined other aspects of media-conflict interactions, including the role of televisionFootnote 8 and radioFootnote 9 within conflict zones, especially during the dissolution of the former Yugoslavia and the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.

The CNN effect scholarship and related research has provided important insights into US media influences on policymaking during humanitarian crises. Empirical research revealed contextual factors such as levels of national interest, policy certainty and types of humanitarian response.Footnote 10 This research built a deeper conceptual understanding of the variety of roles the media play as well as encouraged new conceptualisations of how and why the media influence government responses to conflicts. Theoretical progress also led to multidirectional conceptualisations of government-media relationsFootnote 11 that highlighted the significant influence that political elites have over media coverage, and the circumstances in which media can play a more independent and influential role. Research has also shown that media can play a more divisive than constructive role during critical moments.Footnote 12 Several scholars also point to the ability of rival actors to influence international media coverage to support their cause, from agenda setting and framing to facilitating diplomatic and military assistance.Footnote 13

Owing to the focus on armed responses during humanitarian crises, the analytical centre of gravity of the CNN effect literature focused on media within ‘hot’ phases of conflict. Less attention has been paid to the roles of media in postconflict reconstruction and peacebuilding, peace processes,Footnote 14 or conflict prevention.Footnote 15 Existing research on conflict prevention and peacebuilding has highlighted the inadequacy of the media as an early warning or preventative actor.Footnote 16 As journalistic news tends to focus on drama, it generally avoids situations that have yet to reach a crisis point. Conflict coverage is also selective and significant violent conflicts are often ignored such as recently in the Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.Footnote 17 Such assessments have fed into a broader set of criticisms concerning the media tendency to encourage short-term ‘firefighting’ responses by the international community that shift resources away from conflict prevention and peacebuilding. An extensive literature has also emerged critiquing the top-down and ethnocentric nature of what were usually US and Western-led responses and the failure of journalists, humanitarian actors and policymakers to adequately comprehend the needs of people in war-torn societies.Footnote 18 Little work has been done to unpack this assumption or explore more systematically the relationship between media and humanitarian responses.

The geopolitical and technological context of media-conflict interactions has, however, changed over the last 15 years and scholarly attention needs refocusing in four ways. First, it is worth modifying the sharp distinction between ‘wars of national interest’ and intervention in ‘other people’s wars’. On the one hand, wars of national interest are now frequently fought within the context of a humanitarian narrative; witness the ‘peacebuilding’ dimensions of the Western military action in Iraq and Afghanistan. On the other hand, most ‘humanitarian’ interventions in the 1990s involved substantial elements of national interest and realpolitik.Footnote 19 The lines between these different types of conflict are further blurred by the ‘war on terror’ and the asymmetric nature of many contemporary conflicts.Footnote 20 Rather than maintaining a sharp distinction between ‘our wars’ and ‘other people’s wars’, or wars of ‘national interest’ and ‘humanitarian’ war, etc., we can understand contemporary conflicts as lying somewhere along a continuum which includes space for a number of different media-conflict interactions. The theory development detailed in this article is intended, therefore, to be applicable to all of these various media-conflict formulations.

Second, the research on foreign policy-media relationship focuses on Western, mainly US, cases, and this needs rectifying. This is partly due to renewed recognition of the importance of the ‘glocal’/local dimension of conflicts, and the need to move beyond research which assumes that Western media and Western foreign policy is the beginning and the end of the story. But it is also demanded by the nature of the twenty-first-century media environment, which involves global and local media operating in the context of the Internet and the ubiquity of digital communication. This new reality also establishes a third reason for broadening the focus of media-conflict research to include the patterns of multiplication, fragmentation, and new communication technology, and we detail these developments in the next section.

Fourth, given the nature of the contemporary media environment, in which traditional news media outlets coexist alongside (and contribute to) social media such as Twitter and YouTube, whilst mobile phones and Internet access are widespread, it is important to work with a broad definition of what constitutes politically significant media, and move beyond the traditional focus on mainstream broadcast news media. At the same time, while engaging with and within cutting-edge social media is essential for media research, an overreliance on any one technology that might be portrayed as the ‘future’ of communication risks becoming an obsolete venture before studies are even funded, let alone published. Moreover, each conflict setting may see different social media actors in driving roles: SMS and Facebook messaging may be ubiquitous in one conflict, Twitter and YouTube in another, and locally-rooted social media in yet another. Noting recent works on specific social media and their respective abilities or lack thereof, to serve as truly path-breaking tools or mechanisms of policy influence,Footnote 21 we maintain focus on the influence of all media outlets upon policy, conflict, and peacebuilding as opposed to encouraging point-specific studies on any one means of internet or social media communication. Thus, we recommend an ‘information ecology’ perspective on new media,Footnote 22 allowing researchers to flexibly study change as new technologies and institution morphologies present themselves while tempering the importance of chasing the ‘latest’ technologies in the field. This distinction enables scholars to decouple the increasingly complementary and melded – but distinct - roles of technology in conflict and peacebuilding from the role of media.

With these points in mind, we now turn to a fuller discussion of two of these key areas, points two and three above, which require greater theoretical and empirical engagement: (1) the multiplication and fragmentation of media outlets and their subsequent impact upon twenty-first-century newsgathering technology; (2) the role of local-level media such as media outlets based in conflict districts or regions or national media that cover conflicts in their immediate periphery.

Changes in the media environment

Changes in the media environment inevitably introduce uncertainty about the validity of the existing research on media-conflict interactions. Today’s range of new, competing and alternative media outlets has increased along with a rise in global demand. It has also become more diverse with the rise of specialist and niche media sites challenging the dominance and legitimacy of traditional news, and it has converged as previously discrete media including print, television, radio, and interactive technologies have coalesced around their internet footprints.Footnote 23

Throughout the world, the multiplication of media outlets and audiences who have access to them are staggering, even in developing states. For example, Sudanese citizens living in Khartoum may be informed about events in the western Darfur province through reading a Khartoum-based paper, listening to radio, watching TV reports, viewing Al Jazeera’s perspective, or reading Internet reports or an activist blog in the US.Footnote 24 Especially in fragile states, informal (local) media flows are increasingly important and relied upon.Footnote 25 Likewise, diaspora communities can now stay much more actively and easily engaged by following not only news at the local and national level of the country they live in, but also by following local and national news streamed from their homeland through the Internet. For example, Pakistanis living in Norway may follow Pakistan’s engagement in the ‘War on Terror’ through Norwegian news channels and newspapers, but also through regional European and international news sources, and also or instead, through Pakistan-based news outlets. In addition, political leanings have become marketised in many media environments, encouraging the fragmentation of the media landscape as outlets seek to develop unique ‘voices’ in the field – and often adjust their reporting of news to suit a political agenda. In conflict zones, this has encouraged media outlets to trumpet xenophobic, jingoistic, and otherwise violence-inducing information in the name of increasing market share, and has also encouraged conflict actors themselves to establish media outlets. Coverage has become more fragmented, polarised, and opinionated as outlets have multiplied.Footnote 26

While the number of media outlets available to audiences has proliferated, the technologies available for news gathering have profoundly changed. For journalists, lightweight and portable editing and satellite communication equipment allows easy and rapid reporting from conflict zonesFootnote 27 and potentially decreases the reliance and influence of official sources upon reporting. But newer forms of journalism have also emerged. Mobile phones enable video and photographs to be instantly taken, and then rapidly circulated over the Internet, thus enabling the emergence of citizen journalism.Footnote 28 Internet platforms including Twitter and Facebook and other ‘Web 2.0’ communication media have also dramatically increased the flow of news information between individuals and can themselves serve as major sources of breaking news.Footnote 29 Overall, it is often argued that the contemporary media environment has created a myriad of diverse, pluralised, and fragmented interconnections and information flows.Footnote 30 At the same time, media multiplication and fragmentation diversity has been simultaneously contained or constrained by the continued predominance of major corporations’ ownership of media outlets and the impact of capitalism on the fabric of the Internet.Footnote 31

The net effect of these developments is ambiguous. As with the CNN effect debate of the 1990s, many scholars and observers are drawing links that assume that policymakers are first engaged viewers themselves of real-time news before they become active participants in the news cycle through policy action. Certainly, the range and potential persuasive power of today’s news media is impressive and includes traditional news media in both their online and traditional print and broadcast incarnations, the global news media such as CNN International, BBC World and Al Jazeera, and online media including alternative websites and social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook.

At the same time, the prevalence of asymmetric conflict, exemplified by Al Qaeda and the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), and conflict associated with the ‘War on Terror’, combined with the highly visual nature of the contemporary media environment has, according to some, elevated the importance of image warfare. Scholars argued, for example,Footnote 32 that groups such as Al Qaeda (and now ISIS) are highly adept at projecting power and influence via emotive and threatening images.Footnote 33 For these scholars, images have become as powerful, if not more so, than traditional military capabilities. For other commentators, new media appears to shape public understandings of conflicts rapidly and in unforeseen ways, with certain events suddenly becoming a central focus of attention, while other also seemingly newsworthy issues remain in the shadow. Witness the outcry from Invisible Children’s Kony2012 video and its backlash, Nobel Laureate Malala Yousafzai’s struggle in Pakistan and her subsequent international campaign supported by western media agencies, and the avalanche of Twitter follows for Libyan and Syrian citizen journalists by concerned global citizens as they attempted to gain unvarnished access to ‘truth’ in reporting on the Syrian conflict and ISIS atrocities.

Critically, however, new media technologies might variously empower or disempower political actors, as increased visibility is not necessarily synonymous with increased political influence. Patterns of fragmentation and multiplication and technological developments appear to muddy the processes by which political actors attempt to promote coherent frames or ‘strategic narratives’ that can influence and shape conflict responses.Footnote 34 For states involved in offensive military action, such as the Western operations in Iraq (2003–9), Afghanistan (2001–present) and now against ISIS, such developments in the media environment appear, at least to some, to reduce the ability of powerful states to influence and mobilise support for their actions, amongst domestic and global audiences and populations within conflict zones.Footnote 35 The diverse new media environment may have contradictory consequences for international responses to conflict and humanitarian crises, for example, by increasing the range of media available to actors trying to mobilise responses to a crisis, but decreasing the ability of any one group to influence public and political awareness, precisely because of the diffusion of media outlets and the fragmentation of audiences. The quality of awareness also needs to be considered, as heavy media attention to misconceived aspects of a conflict can have deleterious consequences.Footnote 36

Key questions are whether the domestic and global public spheres are becoming more information rich at the expense of timely responses to humanitarian crises, what are the effects of different types of media on political action, and do the media facilitate or complicate such action.Footnote 37 While social networking and mobile communications might facilitate certain media-conflict relationships, these might differ from those triggered by ‘global’ media outlets such as CNN and Al Jazeera. With a nearly full adoption rate by Western journalists in less than five years, Twitter in particular may actually be serving as a source of over-reliance or echo chamber for communication professionals. Moreover, recent evidence suggests a distinct sequencing of the media-politics cycle, with an upsurge in social media coverage often following rather than sparking more traditional media coverage.Footnote 38

Today’s information environment also shapes the ways in which publics, policymakers, humanitarian actors, and actors within conflict zones themselves understand conflicts. In some cases, this environment serves to multiply the existing internal factions in a society, working against the building of mutual understanding amongst and between conflicting parties. In others, the news media is seen as a tool for conflict resolution and bridge-building, even in the context of multiplication and fragmentation. Alternative news sources and social media are becoming integrated in news reports in ways that appear to increase transparency, awareness, and understanding, but these technologies may simply perpetuate greater fragmentation, or be largely peripheral to mainstream media representations of conflict.

Overall, the nature and dynamics of connected, but fragmented, public spheres and the ways in which the locus of discursive power can shift in this media environment certainly necessitates moving beyond traditional state-centric Western political communication models dominating the literature reviewed earlier, and toward a genuinely global understanding of media dynamics that enables understanding of the ways in which the visibility and invisibility of conflicts is shaped. In particular, these developments require a new focus on the local conflict-media dynamics.

The forgotten importance of the local and the ‘glocal’

As a counterbalance to the focus of existing literature on the foreign policy of Western governments and media and their relationship to domestic audiences, the local media level should constitute a core focus of future media research for a number of reasons. First, local and regional media dynamics within conflict zones are equally important. Media organisations are now present in previously underserved peripheral and rural markets, particularly in the developing world, and various non-elite actors seeking to influence political processes have new forms of access to media. Today, the time between the outbreak of violent conflict and information reaching international audiences is significantly reduced, no matter how remote a conflict might be. Conflict actors themselves may act as media outlets, releasing video and other electronic materials designed to draw attention to their cause. Even if conflict events are not determined to be ‘newsworthy’ by international media actors, social media and other Internet-based outputs fill the gaps.Footnote 39 The much faster pace however, is potentially damaging upon the reliability, authenticity and accuracy in representation of local actors as this material is often assumed to have comparable precision to that produced by major media outlets.

Second, just as the media context is changing, so too is the international agenda for conflict and conflict-response. The 9/11 attacks have increased criticisms of Western reporting bias among different audiences, particularly in the Muslim world. This is a process of fundamental transformation where new social media have been seen to play a key yet underexplored role. International organisations and donors are showing more sophisticated understandings of the complexity and trajectory of violent conflict, and increasingly argue that bottom-up processes should be accommodated. The UN, World Bank, and others have produced a range of new conflict response policy documents that call for a fuller picture of local aspirations and conditions in conflict zones.Footnote 40 Orthodox and institutional means of information-gathering such as embassies and diplomatic channels, must be augmented by other methods, including the media and social media.Footnote 41 The ‘Arab Spring’, the recent disintegration of the Middle East and other developments continue to catch Western governments and other ‘experts’ off guard, and have reinforced the idea that the ways governments, international organisations, and other actors gather information from conflict and preconflict regions must be reassessed.

Third, interaction between conflict and reporting at all levels affect conflict dynamics and policies. This includes study of the creation and promotion of local media narratives arising from local-level conflict events, and the changes these narratives undertake as information trickles up from the local, through the national and the international and often back down to local politics and local media. Two current examples of this are the understudied local-international interactions in the ongoing Ukraine and Syrian conflicts, and how duelling subnational, national, regional, and international accounts influence local perceptions. These narratives impact upon conflict response policies. On this front, the ‘event-driven news thesis’Footnote 42 comes up across a range of the media-state relations literatureFootnote 43 as a key variable concerning the disruption of prevailing power-relations between political actors and media. Research that traces how events cascade through global media, global politics, and then through domestic politics, and determines the effects in terms of substantive political influence is much needed and can make a major contribution.

Fourth, the ‘local’ is where the conflict takes place, yet it is often distorted, romanticised or ignored in media and policy framings.Footnote 44 Local-level media within conflict zones is a potentially powerful actor, especially vis-à-vis national-level ‘official/establishment’ media. Often conflict actors (local, national, or international) seek to promote a hegemonic narrative of the conflict whilst innate ethno-centricism frequently shapes the way in which the suffering of one or other side in a conflict is differentially framed.Footnote 45 The multiplicity of media sources, and the peculiarities of local media, means that proto-hegemonic narratives may be contested or rebutted.Footnote 46 New media also makes the circulation of alternative scripts more accessible, but it can come at the expense of reducing the availability or penetration of more established and vetted news sources in favour of more sensationalist or polemical alternatives. As ‘grand schematic visions’ of conflicts are circulated through international media they rarely do justice to local complexities and needs. The study of disparate local media sources, especially social media voices, can provide a window into these subnational variations in ways that looking at national-level media alone cannot.Footnote 47

Fifth, for local conflict actors, dispersing news about their struggle is an increasingly important tool to obtain international recognition, legitimacy, or material resources.Footnote 48 By distinguishing characteristics between deliberate conflict actor media strategies, and internal outcries for help or external calls to ‘Do Something!’, we may be able to unlock how local conflict actors engage with local and national media to win ‘hearts and minds’ in their own societies, and thus directly or indirectly shape the ways local conflicts are framed. There is also over-writing of local narratives and local experiences, by imposed narratives as local understandings of conflicts have been ‘reconstructed’ and ‘translated’ into conflicts more understandable to outside observers.Footnote 49 This renders as malleable the ownership of narratives and connects with recent literature on the experiential aspects of war.Footnote 50 It also risks turning the victims, participants, and bystanders of conflicts into ‘subjects’ with limited agency and limited ability to tell their own story.Footnote 51 Thus, it is necessary to take a step back from the ‘conceit’ of many contemporary Western epistemologies and methodologies, and recognise that there are limits to the extent to which the complex interactionism of a conflict zone can be rendered into neat schemata for global audiences.Footnote 52

Multilevel hybridity: Exploring new media-conflict interactions

What should be clear from the discussion thus far is that, from global to local levels, the degree of interconnectivity enabled by digital Internet-based media creates a multifaceted environment and one in which local-level media-conflict dynamics interact with global and Western media-policy dynamics. In order to make sense of these complex relationships, Mac Ginty’sFootnote 53 concept of hybridity, in combination with Gilboa’s concept of multilevel interactions, can be employed to understand dynamics between political actors and media.

Hybridity

Hybridity suggests that peace, security, development, and reconstruction in societies emerging from violent conflict tend to be a hybrid between the external and the local. In peacebuilding, internationally supported peace operations meet local approaches to peace that may draw on traditional, indigenous, and customary practice. Hybridity does not envisage the simple joining together of two separate processes to create a new third entity. Instead, it rests on the notion of ‘prior hybridity’ whereby all actors are the result of constant processes of social negotiations, conflict and coalescence.Footnote 54

Hybridity is a means of capturing complexity and can make comprehensible the kinds of interaction between local, national and international media, audiences, and conflict actors discussed in the previous section.Footnote 55 The analytical lens offered by hybridity allows scholars to maintain the importance of agency at all levels, viewing the media as both a bottom-up and top-down enterprise, in which power is distributed across different types of media and in a manner that captures the significance of the all important local/glocal dimensions highlighted earlier. Hybridity also encourages a close look at the local media reactions to top-down (national and international media), and at the variance of alternative and new media without excluding more traditional forms of media.

Moreover, hybridity allows us to investigate how media shapes conflict dynamics, with a range of factors uniting to produce a complex landscape of reportage, dissemination and understanding of policy change. Here hybridity appears particularly suited to the understanding of the patterns of multiplication and fragmentation discussed earlier. By focusing on relationships and interactions, hybridity encourages scholars to examine multiple information transmission routes and captures the impact of a complex media environment on the evolution of conflict and peace. This involves the dissemination and evolution of media narratives, as they experience distortion, blowback, and change. Important here is the sequencing of the news-conflict relationship, and the attempted and actual ownership of media narratives.

The hybridity concept helps us understand how complex media dynamics impact upon the policymaking and public spheres where attitudes and policies towards conflict situations are debated and decided. Diaspora engagement with conflict can illustrate the actionable components of hybridity of media spheres in practice. As a consequence of immigration to Europe, migrants’ sustained transnational ties and developments in communications technologies over the past decades, interest in media and minorities in a multicultural Europe has emerged.Footnote 56 But mainstream media engages with and represents minority populations, and alternative and minority media provide counter-voices to dominant discourses. The latter is especially evident when minority communities in Europe have links with secessionist or insurgent groups in their country of origin.

The media scene in contemporary Europe is a stage where conflicts of interests and struggles over identity and power of definition are played out, where a hybridisation of the media sphere is evident. Much of this interaction occurs at the transnational level, with dedicated diaspora TV channels, kinship networks, governments, INGOs, and others all attempting to influence the conflict narrative.Footnote 57 Using hybridity encourages a look beyond the ‘official transcripts’ of government statements and state-run media, to the multiplicity of media offerings, how they interact and competitively seek to influence conflict-response policy. The use of media to influence conflict situations is not new, but changes in communications technologies have increased the capability of conflict actors – especially in the diaspora – to use media as a strategic tool. The movement for democratisation of Myanmar, with their radio, television, and website ‘Democratic Voice of Burma’ is an example of an opposition group that has used media strategically, both in the European diaspora and vis-à-vis the country of origin population and government, as well as an official lobby tool targeting the international community.Footnote 58

Multilevel analysis

Whilst the concept of hybridity provides a useful organising backdrop, greater analytical precision can be obtained by its integration with Gilboa’sFootnote 59 six levels for media analysis. This helps to clarify and consolidate the multilevel approach to assessing how media on the local, national, regional, international, and global levels interact,Footnote 60 and adds important research space to the existing national-level focus of media’s influence on policy outcomes. An example taxonomy is listed thus:

Local: City / district-level outlets not intent on or capable of reaching national audiences

National: New York Times, CNN-US, BBC-UK, CNN-IBN (India)

Regional: Al Jazeera (Arabic), Al-Arabia, SABC, TeleSUR

International: VOA, Al Jazeera International, Russia Today, France 24, CCTV

Global: CNN International, BBC World, International New York Times

Glocal: Internet based platforms: Facebook, Twitter, YouTube.

The main differentiating criteria are geography, contents, types of audiences and ownerships. The local media, mostly commercial, reaches very limited audiences who live in a town, a city, or a district. Local outlets include radio and television stations and local newspapers or community bulletins. They may carry a few programmes from national outlets on radio and television, but are mostly interested in local news and features. The next level, the national, both public and commercial, often covers the political boundaries of nation-states. It presents both national and international news. The latter is usually perceived by editors as relevant to the entire population in a state. The elite press presents more international news while the popular or tabloid press much less. The regional, both public and commercial, usually overs an area distinguished by language, history, culture, or religion such as the Middle East or Latin America. Regional media such as Al Jazeera Arabic, both reflect common regional interests but also define and reinforce them.

Both the international and the global media reach global audiences. International media present news and commentary from the perspective of a particular state (at times in languages other than that of the host country), while global media have no such official allegiance (unofficial allegiances and frames being another matter). The international media is usually owned by governments or has some affiliation to a governmental agency, while the global media are mostly commercial like CNN International or a relatively independent outlet such as BBC World. The global media tend to have more bureaus and reporters than the international media and cover a wider variety of global issues, while international media tend to cover issues mostly relevant to the states that own them, and from their narrow or biased perspectives. The nature of global media can also be demonstrated by the differences in programmes and audiences between CNN-US and CNN International or between BBC UK and BBC World, where the first are national media and the latter global media.

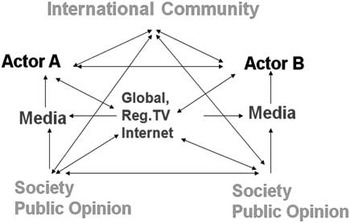

The glocal level reaches both global and local audiences.Footnote 61 Glocal presents local knowledge and information, in the case of this study on conflict and peace, in a global context; and global issues in a local context. Glocal outlets include primarily social media networks with global reach such as Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and YouTube. The glocal often has stronger elements of advocacy and human rights bases than their traditional media counterparts. This allows for study of the interaction effects between media, conflict actors, and others engaged in conflict settings. The actors include governments, leaderships of NGOs, and the ‘international community’, which primarily refers to the United Nations. The media includes all the levels. A simplified chart of potential interactions is illustrated in Figure 1.Footnote 62

Figure 1 A framework for multilevel media analysis.

Interactions need not be limited to the actors listed here, as there are often multiple sets of conflict actors, public opinions, and competing media and Internet narratives. Figure 1 is designed to illustrate complementary and researchable interaction effects between medias (for example, how ‘new medias’ inform ‘traditional media’, and vice versa) and between medias and actors at multiple levels of analysis. It also allows for the fact that media actors themselves can intervene in conflicts and attempt to move them in certain directions, for example, through calls for mediation. Further, mapping glocal interactions allows scholars to move beyond the traditionally simplistic phases of preconflict, conflict, and postconflict.

Gilboa also distinguished among four stages of conflict based on a critical condition and a principal intervention goal: onset-prevention, escalation-management, de-escalation-resolution, and termination-reconciliation.Footnote 63 Much of existing predominantly Western research focuses on escalation and conflict resolution, while the other not less important phases of prevention and reconciliation are neglected and under-researched. This bias aligns with the epistemological conditions affecting conflict research in general, where centres of research including think tanks, universities, and publishing houses, are usually in the Global North, to the deleterious influence of research outputs and study foci.Footnote 64 Focus upon interaction effects at all the media levels and conflict phases can allow researchers to escape from the current traps of conflict research, framing analysis in ways that can display value for all parties involved.

Our multilevel hybridity approach can be applied using both contentFootnote 65 and framing analysis,Footnote 66 and can involve quantitative analysisFootnote 67 or qualitative readings of smaller subsamples of media coverage.Footnote 68 It also meshes well with political communication modelsFootnote 69 and theoretical approaches such as field theory,Footnote 70 and can also succinctly assess political variables against media variables. In particular, the use of new online news archivesFootnote 71 encourages comparative approaches of both online and traditional news media formats and holds significant promise.

Multilevel hybridity: Five research streams

We visualise five broad streams of forward research on glocalised conflict: from the national level to the global; from the local to the global; from the glocal to the local; from the global to the global; and from the near local to the far local. These streams are not designed to serve as a typology of conflict actor engagement with media given the obvious overlap and fluidity of the actors and media sources themselves. Rather, they are a way to help us understand and contextualise the researchable interactions that are currently taking place.

First, the national level to the global level stream. This stream builds upon and develops the classic literature on war and media, discussed earlier, and takes seriously the role that powerful states play in terms of attempting to shape and influence the communications environment. As part of a top-down process, powerful states will persistently seek to influence local, domestic, and global audiences with respect to a conflict, especially when core interests are perceived to be at stake. This occurs most obviously during wars initiated by powerful states, as witnessed in recent years during the influential ‘public relations’ campaigns led by the US and UK governments aimed at convincing domestic and international audiences about the threat posed by Iraq.Footnote 72 Other recent research has highlighted the ways in which powerful states shape media and public understandings of conflicts such as the 1994 Rwandan GenocideFootnote 73 and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.Footnote 74 Future research can go further to study organised persuasive communicationFootnote 75 campaigns by great powers and how these are variously adopted, contested, or rejected by local, national, and global media.

The stream from the local to the global captures the bottom-up processes whereby local actors build awareness of conflict, often by conflict actors themselves, in an attempt to (re)frame international understandings, agendas, and narratives. Often attempting to highlight material that the ‘traditional media’ might overlook, local actors drive these streams in an attempt to win international allies against their domestic opponents. Media-savvy insurgents such as ISIS and the #BringBackOurGirls campaign against Boko Haram in Nigeria show how both conflict actors and engaged international citizens have used Western media houses and websites as platforms for their attempts to shape and control international narratives, highlight abuses or celebrate them, and even set agendas for peace and ceasefire negotiations. Future research could explore how conflict actors approach global media houses, why the houses accept or reject such invitations, what both sets of actors believe is gained by such interactions, and the forward impact of such activities.

The stream from the glocal to the local consists of uses of global social/news media by local actors, and how the support they get through these channels is reported back to the ‘rest’ of the local level as a legitimisation mechanism. It is also a way for international advocacy and humanitarian actors to show support and solidarity during times of abuses or hardship as well as provide an outlet for engaged INGOs to ‘Do Something’ in a rapid manner. The belief is that elite international engagement serves as a de facto watchdog for otherwise vulnerable local actors who might otherwise be silenced by oppressive regimes, while also allowing international agencies to ‘get local’ in their engagement. One such example is the use by indigenous communities in Colombia of Twitter and other social media platforms – amplified by alliances with media-savvy Western INGOs – to attempt to influence Colombian journalists to argue for their inclusion in the ongoing national peace process. Research could explore the value of international support for local agitation, raising awareness for government services that operate side-by-side a health INGO’s operations, and the potential for backfire when international chatter undermines governments that rule through oppression.

The stream from the global to the global is perhaps the most publicly visible today, referring to the transfer of information between those already heavily networked and connected to global opinion making. Here we find the world’s Twitterati, YouTube conflict celebrities, and other non-policymakers who are assumed to drive public discourse on peace and conflict issues, from the anti-slavery campaigns led by CNN’s Anderson Cooper and Christine Ananpour to the media-heavy roles played by George Clooney and Angelina Jolie as special representatives to the United Nations. There is a belief that these celebrity conflict tastemakers have the power to inform and encourage action merely through 140 character blasts to their millions of followers. Research could explore how public engagement is influenced by such actors, how ‘going viral’ influences policy, and if global social media is merely an echo chamber of elite opinion in areas where few have constant internet access.

The stream from the near local to the far local is perhaps the most hidden to ‘mainstream’ media. It concerns direct local-local advocacy interactions enabled through the advent of global access to real-time communications as a change agent. These interactions are not designed to reach large audiences, but rather engage distant communities with kinship or other ties in a targeted manner. This can be best illustrated in terms of diaspora engagement. Diaspora involvement in conflict, through supply of human and material resources is not new, but has gained significance with new media and the increased real-time presence that this allows for. However, diaspora populations contribute in a multitude of small ways in both conflict and postconflict settings.Footnote 76 This is perhaps the least understood communication network of the four, but potentially the most promising, as these interactions often provide space for less extreme diaspora actors, whose voices are often ignored or shouted away by their radical counterparts in the media, to positively contribute away from the glare of international media.

Whilst these five streams serve as a starting point for research, the concept of hybridity reminds us that mediated events and conflict resolution across these different levels bleed into and mutually influence each other and are both fluid and interrelated. For example, a violent event within a conflict zone may be mediated through global media as a major atrocity that then shapes policy responses at the international level.Footnote 77 Alternatively, lack of exposure to a crisis or coverage that distances both the public and policymakers from a particular conflict, may significantly hamper attempts by international actors to pursue conflict resolution strategies. Within the contemporary information environment, as local actors respond to international reactions, and international actors respond to local events, reciprocal and dynamic patterns of influence emerge and evolve. Research could explore the ways in which real-time communication is being used within near-local to far-local interactions, and what implications these new forms of communication have for affecting change. Future work can refine the nature of these streams, discover new ones, and seek to understand their comparative influence on policy for given types of conflicts or humanitarian disasters. These flows can serve as useful tools to better approach the media-conflict realities that currently unfold.

Conclusion

This study has identified the shortcomings of existing research paradigms on media-conflict relations. The CNN effect framework was a useful tool to understand the effects of global news television networks on the conflicts of the post-Cold War era. Yet the dramatic changes in the communication and conflict worlds of this century, and the speed by which events reach an international audience and the proliferation of media sources have not only impacted upon how media actors relate to conflicts, but more broadly, on how we as publics and policymakers understand, interpret, and respond to conflict situations. In particular, patterns of media multiplication and fragmentation, coupled with advances in news technologies have injected considerable uncertainty and potential fluidity regarding media-conflict interactions in which, more than ever, local-level conflict and media dynamics demand analytical and empirical attention. Media is not only a vehicle to inform about conflicts, but has also become inherent within conflict dynamics. It is therefore important to increase awareness about this co-constitutive relationship through sustained, comprehensive research about the interaction effects of media in contemporary conflict environments.

The multilevel hybridity approach introduced in this study has the capacity to describe and explain how new global communication connectivity influences the dynamic and complex media-conflict relationship. The connection between the external and the internal in this hybridity approach is integrated with the six levels of media in order to emphasise the local and the glocal in addition to the national and global dimensions, which traditionally have been the focus of conflict and media research including the CNN effect debate. In support, we have outlined several potential forward research directions that prioritise interdisciplinary approaches and close dialogue with practitioners. When combined with systematic applications to case studies in all regions of the world, we can further unpack these new ties and yield stronger understanding of the contemporary relationship between media and conflict.

Utilising the approach mapped out in this article, future research can address a number of pressing questions: to what extent, if at all, has power diffused away from states and other powerful actors seeking to mobilise support and gain strategic advantage? Have developments in news gathering technology, the emergence of social media, and the ubiquity of personal mobile communication enhanced or diminished the potential for timely response to conflict and humanitarian crisis? In what ways do the global and glocal media dimensions enhance the ability of actors both within and outside conflict zones, for example, diasporas, to promote their agendas, and how does this in turn shape global and international responses? Using our approach to explore these and other questions could significantly help to advance our understanding of media-conflict interactions in the contemporary era.

Acknowledgments

The authors deeply thank Roger Mac Ginty, Marta Bivand Erdal, and three anonymous reviewers for their invaluable input, comments, and improvements.