It is not down on any map; true places never are.

[Herman Melville, Moby-Dick; or The Whale, 1851]

The map is not the territory.

[Alfred Korzybski, Science and Sanity, 1933]

Introduction

In February 2017, a professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in India gave a lecture at an academic conference on ‘History reconstrued through literature: Nation, identity, culture’ held at Jodhpur University in the western Indian state of Rajasthan in which she spoke about Hindutva (the political use of Hinduism by right-wing nationalists) and showed an upside-down map of India.Footnote 1 She later explained her reasons for this depiction:

This was in the context of my critique of the Hindutvavaadi and RSS [influential Hindu right-wing organisation] notion of nationalism, which sees the nation as a body, the body of the mother. I said the RSS Bharat Mata [Mother India] can be easily transposed on to the map of India we are familiar with, with Kashmir as the head … but if we turn the map the other way round, which is still an accurate depiction of the region, suddenly you can see that the nation is not a natural unchanging object, but something constructed by people.Footnote 2

The next day there was a backlash by student groups affiliated with the Hindu right wing, who forcibly stopped classes and demanded punishment; a police First Information Report was filed against the professor, and the academic who organised the event was suspended.Footnote 3 In 2021, the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh filed charges of treason against the head of Twitter in India over a controversial map of Kashmir.Footnote 4

In April 2019, Taiwanese students submitted a petition with 10,000 signatures to the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) protesting the school’s decision to change Taiwan’s colour to match China’s on the World Turned Upside Down statue on campus. This decision by the university management had been made after receiving many complaints from Chinese students claiming the statue inaccurately depicted Taiwan as a separate country from the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Faced with protests from Taiwanese and Chinese students, the university held a meeting in an attempt to mediate between the demands of the two sides.Footnote 5 When LSE announced its decision to proceed with the change, the then Taiwan president Tsai Ing-wen and foreign minister Joseph Wu condemned the move, arguing that Taiwan is a sovereign democracy with a democratically elected president.Footnote 6, Footnote 7

These instances demonstrate the ostensible power of cartographic representations not only in terms of cultivating a strong sense of national identity within the minds of citizens, but also in terms of their ability to inspire actors to effect social changes within the civil societies and domestic spheres of other countries overseas in line with this imagined territory. The vignettes above confirm that maps are not mere representations of territories; depictions of Kashmir and Taiwan highlight how such representations are projected in a force field of geopolitical power. Both territories motivate Indian and Chinese nationalist political positioning, and this political positioning occurs not only within Indian and Chinese domestic politics, but also increasingly on a transnational, global scale. Both India and China have active state-sponsored organisations and large diaspora populations that mobilise to enact this political positioning towards overseas governments and societies. International Relations (IR) scholarship may have been oblivious, but the comparison has been observed more than once by Indian and Chinese officialdom. An Indian external affairs minister said as much to his Chinese counterpart on the sidelines of a Russia–India–China meeting: ‘Kashmir is to us what Tibet, Taiwan are to you.’Footnote 8 Similarly, in response to India’s opposition to the ‘China–Pakistan Economic Corridor’ (CPEC) on the grounds it would threaten Indian sovereignty in Kashmir, Chinese state media published an opinion piece justifying CPEC through a comparison of Kashmir and Taiwan: ‘Just like the Taiwan question, Beijing doesn’t object [to] any economic links between Taiwan and other countries including India, because economic activities won’t alter China’s sovereignty over the island.’Footnote 9

Cartographic representations of Kashmir and Taiwan act as sites upon which Indian and Chinese state power is exercised. Both regions have long been a theatre of political dispute that is internationally known, yet Kashmir cannot be recognised as a political dispute per India, and Taiwan cannot be referred to as a separate, independent state per China. Notwithstanding the differences in the communal and party-political endogenous dynamics in the two regions, a crucial parallel is the divergence between the de jure and de facto nature of these two entities. While the maps by and in India and China fixate on a certain representation, this is comprehensively belied by the de facto status and functioning of the territories. We are interested in how the governing logics of global visibility and legibility for these two regions are heavily underwritten by constant efforts on the part of Indian and Chinese state power.

To this end, we focus on what we term ‘cartographic imaginaries’ of Kashmir and Taiwan that are crucial to Indian and Chinese nationalism. In the first section of this article, we expound our concept of cartographic imaginaries, locating it in relation to existing literatures on critical geography and cartography and distinguishing its significance and import for the field of IR. We argue that interrogating the cartographic imaginaries of Kashmir and Taiwan by India and China reveals systematic and significant analytical dynamics in relation to representation, nationalism, and diaspora in both cases. Bringing together an interrogation of these two cases is itself an analytical innovation, since no IR work has hitherto considered this comparison. Our analysis relates to significant current concerns in IR regarding critiques of imperial cartography, the impact of new rising powers on global order dynamics, and the transnational governance of diaspora. In the next sections of this article, we present in-depth investigations providing a range of examples to trace the Indian and Chinese states’ respective efforts, both domestic and international, to construct and control cartographic imaginaries of Kashmir and Taiwan. In our conclusion, we foreground how our framework of cartographic imaginaries illustrates the clear connexions between affect, visuality, and state power, while at the same time offering empirical insights into non-Western projections of imperialism on a global scale. We highlight several ways in which our analysis creates theoretical interventions relevant to studies of power in global politics, and how these can help interpret other cases of state transnational productive power, presenting directions of enquiry for future scholarly work.

Cartographic imaginaries

The relationship between geography and cartography has witnessed multiple strains over time. As a result, there is a rich legacy of work that opens cartography and the history of cartography to post-positivist critical investigations. Scholars across disciplines (for example, J. B. Harley) have sought to reveal the non-empiricist nature of maps beyond depiction and navigation.Footnote 10 Harley referred to how maps of early modern Europe functioned within practices of secrecy, censorship, and suppression that were used by states to bolster their stability and durability and help them acquire, maintain, and legitimise power; cartography is a form of political discourse, and deliberate cartographic silence/silencing (the intentional and unintentional suppression of knowledge in maps) is thus political speech, since it reproduces and reinforces specific political and cultural values.Footnote 11 Edney appraises these contributions to critical cartography,Footnote 12 as does Cosgrove, noting especially the radical nature of later work by Harley whereby ‘all maps [are] vehicles for the exercise of power and its uneven social distribution’, leading to a ‘commitment to deconstruct all aspects of the mapping process’.Footnote 13

While cartography in the previous centuries had sought to establish itself as a science, critical cartographers from the mid-20th century onwards in the Anglo-American and European worlds have often been attentive to the ways in which maps and map-making are a practice of power, often gendered and imperial power. An eminent voice in the field, Edney, notes that cartography is the reduction of complexity;Footnote 14 maps are not mere representations, they are not even simply things; maps are interested constructions, they function within discourses and are involved in meaning-making as social texts that seek to regulate and control.Footnote 15 Certain kinds of modern imperial maps are also an expression of desire, since maps, depending on the representational strategies, can evoke feelings. Therefore, maps can do much more than lie; they can have real effects. To wit, ‘when the conditions of discourse are just so, then these emotional responses develop into desires and fears that are imposed on territories in an abusive manner. Herein lies the modern power of maps, and their capacity for use and abuse.’Footnote 16 Maps, in other words, are productive. We might see cartography, beyond simple geography, as attempt to elicit affect and provoke feelings that might be harnessed to varied ends. Critical geopolitics too has examined the power–knowledge regimes and practices that underwrite cartography, geography, and geopolitics.Footnote 17

While cartography has long served as the handmaiden of empire, it is a relatively new entrant to the critical theoretical domain of international relations. What we know from recent work is how the mapping of territory has shaped modern statesFootnote 18 and how the consolidation of linear borders in world politics has not been a politically neutral expression of territoriality but a historically specific Eurocentric move of rationalisation that engenders the possibilities of conflicts over territorial sovereignty.Footnote 19 Cartographic ambiguities of the imperial era have paved the way for numerous current conflicts in Asia.Footnote 20 Yao has demonstrated how 19th-century European diplomats’ understanding of geographical imaginaries – seen as a particular type of sense-making that translates ideas about a particular geography into a schema about how it relates to other geographies (following the work of critical geographers and scholars of Orientalism like Said) – played a role in the making of the European International Order, colonialism, and the 1884–5 Berlin Conference.Footnote 21 In a similar vein, Çapan and dos Reis have shown, with the case of Africa and the European East, how 19th-century German imperial cartography proceeded from the geographical understandings of ‘blank space’ to create colonisable land.Footnote 22 More generally, and with reference to multiple European imperial efforts to create new spaces of governance, Lobo-Guerrero et al. have examined the links between mapping, connectivity, and the making of European empires.Footnote 23

This growing body of literature uses insights from critical geography to denaturalise imperial-era border-making, which was facilitative of colonisation. Beyond critiques of imperial cartography, we also wish to explicate two older and related terms that it would be helpful to keep in the background as we develop our argument here: Winichakul’s geo-bodyFootnote 24 and Krishna’s cartographic anxiety.Footnote 25 A geo-body as a construct is not the same as the actual country in terms of either its territory or its sovereignty. It is through the processes of knowledge production that the geo-body is created. A nation is an imagined community, as Anderson masterfully elaborated;Footnote 26 the enrolment into nationalism is a modern affair, and it involves the role of technology, including cartography. A geo-body, as Winichakul traced it for Thailand, does not necessarily overlap with the territorial boundaries of a country; it is not so much a false but an unverifiable representation of a country and one that also draws upon extra-scientific processes of knowledge-making. The geo-body comes to be fetishised as part of a nationhood, it naturalises a certain understanding of the nation and is intimately tied to the historical narratives through which it comes to life.

Along similar lines, cartographic anxiety was a term used by Krishna to refer to the representational practices that attempt, in his case for India, to inscribe and endow a content, history, meaning, and trajectory to a country so that nationality is socially and politically produced through a cartography of in-/out-sideness and in/security. This cartographic anxiety, he suggested, was a subset of a larger post-colonial anxiety, and a prominent signifier of the post-colony. This conceptualisation of cartographic anxiety focuses on the ways in which the inside and the outside of a nation is constructed through written narratives, newspaper reports, and so on. Krishna’s focus is also on the violence endured by the people at the borders of such an anxious post-colony, especially with reference to the border of West Bengal and Bangladesh. The literature on geo-body and cartographic anxiety has highlighted the connexions between cartography and state identity, nationalism, and power.Footnote 27 While the geo-body sought to expand and denaturalise the historical coming-into-being of the nation beyond its verifiable and scientific cartographic calibrations, cartographic anxiety delineated the crisis of the post-colonial condition as one marked by a constant re/iteration of outside/inside and in/secure. Nurtured in the tradition of the nation as an imagined community, both these takes on nationalism and the nation-state are, and have been, important in complicating our faith in being able to perceive a simplistic post-Westphalian world of defined and sovereign nation-states.

Our notion of cartographic imaginaries resonates with these conceptualisations, seeking to extend and innovate through a different focus in a few ways. First, through the use of the term cartographic imaginaries, we want to signal the important role of affect. As Lennon points out, while an imagination is what makes things that are absent in some way present, an imaginary has a constitutive link with affect and ‘may be broadly characterised as the affectively laden patterns/images/forms, by means of which we experience the world, other people and ourselves’.Footnote 28 On this account, imagination supplements perception, but the conception of the imaginary is not an illusion contrasted with a supposed ‘real’, but rather ‘that by which the real is made available to us’.Footnote 29 Here, we might see imaginaries as the affective domain of patterns, images, and forms through which a certain cartographic common sense is maintained. The geo-body of the nation historically comes into being through, among other things, cartographic imaginaries, and cartographic anxiety is one of its motivations.

However, moving beyond this inheritance, our interest lies in elaborating how and why specific cartographic imaginaries (in this case, of Kashmir and Taiwan) are rendered as commonsensical, and in tracing the more contemporary and current effort, which comprises active processes of construction and control of such cartographic imaginaries. Let us explain why the domestic construction of such imaginaries and the international projection of ideational power is key. We conceptualise cartographic imaginaries as a mode of thinking through the present-day imperial ambitions of two significant non-Western ‘rising powers’, India and China. Contemporary IR scholars increasingly see the need to ‘decolonise’ their discipline and move beyond ‘Eurocentric IR’. This critical unpacking of the historical imperial era is not sufficiently carried forward into the present, whereby the imperial ambitions of two of the most significant non-Western powers is ‘forgotten’ by many ‘critical’ approaches both within and beyond IR. Decolonisation beyond critiques of the European past is necessary too, and our analysis of the mobilisation of cartographic imaginaries by non-European actors complements and complicates this growing literature in critical IR. The answers to the question of what specific cartographic practices make possible when and under what conditions, and for whom, are as yet very partially addressed in wider global terms.

We argue that interrogating the cartographic imaginaries of Kashmir and Taiwan by India and China reveals systematic and significant analytical dynamics in relation to representation, nationalism, and diaspora in both cases. As we will demonstrate in the next section, the active processes of construction of cartographic imaginaries in India and China rely upon preferred mapping for representation, accompanied by nationalist education in textbooks, and state-centric media and popular culture narratives. As a result, the active processes of control require censorship of maps, varying kinds of punishment to regulate views for those within the nation-state, and significant effort to police critical voices in the diaspora through corrective guidance, coercive mobilisation, or weaponisation of mobility and access to the homeland. In both the Indian and Chinese cases, Kashmir and Taiwan are constructed as ‘integral’ to the nation-state in a way that is especially accentuated in the hyper-nationalist Modi and Xi eras, which carry the promise on the horizon of a ‘Rejuvenated China’ and a ‘Viksit Bharat’ by 2047 and 2049 marking their 100-year anniversaries.Footnote 30

We want to highlight how bringing an interrogation of these two cases together is itself an analytical innovation. The two cases we examine – Kashmir and Taiwan – have never before been considered together in any IR work. Xinjiang and Tibet have been considered together through the lens of Chinese colonisation, securitisation, borderlands, counter-insurgency, ethnicity or development policy, protest, etcetera.Footnote 31 Tibet and Taiwan have been the subject of some attention via governance of ‘separatist provinces’ lens. Kashmir and Tibet have been compared as conflicts requiring a solution.Footnote 32 Xinjiang, Tibet, Kashmir, and the Indian north-east have also been seen as disputed borderland conflicts.Footnote 33 Yet it is vital that we analyse across entrenched geopolitical frames that are often ‘methodologically nationalist’ in order to uncover the workings of power beyond the idea of regions deserving of attention exhaustively through European colonial experience or exclusively as conflict zones.

We suggest that our comparison is illuminating as it explicitly concerns two of the biggest and increasingly most powerful countries in the world. As Kaul has argued in her analytical bracketing together of Kashmir and Xinjiang through the commonalities of Indian and Chinese colonial repertoires in the contemporary era, although India and China have different experiences of formal colonisation, the ‘moral wound of colonialism’ – a particular indigenous rendering of Western colonial experience that allows for the manipulation of selective histories to suit a promise of a hyper-nationalist futurity – functions in many similar ways.Footnote 34 Inter alia, our comparison gives us insights into the production of successful contemporary non-Western nationalisms and the conditions of their circulation, as well as into the essentials and variations of geopolitical conduct across different states and regime types. The contrast between these two countries’ international behaviours is made too sharply in some respects, given the growing appeal of illiberalism and authoritarianism in India,and the many issues on which the two countries’ actions resemble an unstated anti- or non-Western pole.

We use the entry point of construction and control of cartographic imaginaries of Kashmir and Taiwan as a way of thinking through how Indian and Chinese hyper-nationalisms seek power projections overseas. The role of the diaspora is important in both cases; there is a significant commonality in the unmissable use of ‘liberation’ language to refer to the regions of Kashmir and Taiwan; a punitive response to transgressions; a weaponisation of selective histories; and the learning of important repertoires. Likewise, the inevitability of complete unification; the claim that the people of these regions are compatriots (part of the wider family) yet also at the same time separatists; the attempt at deep penetration of these regions through propaganda; and the creation of distinctions between the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ people of these regions (to support the former who are loyal to the motherland and to chastise the latter) are themes in common.

Specifically, as visual texts, maps are intended to evoke particular kinds of affective reactions. Maps reflect debates, they mourn the loss of national territories through a cartography of national humiliation, and they represent the fears of national disintegration as well as assert a normative image that resonates with national aesthetic.Footnote 35 For present-day post-colonial non-Western countries like India and China, maps do not only construct a nationalist common sense within the country but also create power projections and legitimise political projects by control through censorship and the regulation of speech, text, and media in the diaspora. Indian and Chinese cartographic imaginaries of Kashmir and Taiwan are successful in being more than constructed visually representative arguments; persuasion is complemented by control, that is, coercion through censorship and punitive responses.

We take the nation-states of India and China to illustrate how ideational power is forged and exercised in the global arena. The agents and processes through which knowledge is constructed and controlled illuminate the real-world operations of ideational power. Globalisation and the advancement of technology has opened innumerable and diverse channels through which such ideational power can be diffused and exercised beyond the bounds of the traditional nation-state. Within our conceptualisation of the international, the systematic effort of the nation-state remains a useful unit of analysis because the beliefs, norms, and practices forged within a nation-state can be exported transnationally and impact ‘the international’ through the processes of immigration, diplomacy, etcetera.

Drawing on existing conceptualisations of ‘interpretive communities’,Footnote 36 the Indian and Chinese diaspora can then be thought of as a channel through which the state exerts interpretive control transnationally over cartographic imaginaries of Kashmir and Taiwan. Interpretive communities exercise productive power by defining the rules and norms that become embedded in institutions as well as ‘[setting] the parameters of acceptable argumentation’ around those norms.Footnote 37 Johnstone proposes that in practice, interpretive communities function to impact law and induce compliance with it; they do so by ‘extracting reputational costs for non-compliance’ and by ‘serving as vehicles for transmitting new norms and promoting their internalisation’.Footnote 38 Here, we can also consider Adamson and Han’s recent arguments on ‘diasporic geopolitics’, where they examine how leading migration-sending states that aspire to great power status seek to exert global influence in international affairs through the means of the diaspora.Footnote 39 The transnational exercise of power is conducted through diaspora-engagement policies in relation to the diaspora as economic assets, promoters of ‘civilisational’ politics, and diplomatic assets. Adamson referred to how diaspora politics is being shaped by transnational repression as a means of exercising ‘long-distance authoritarianism’.Footnote 40 Moreover, as a recent Freedom House Report detailed for several countries including India and China, aspects of such repression (for example, the weaponising of citizenship for mobility control on rights to exit or enter the country) are shared by authoritarian and democratic states.Footnote 41 Though these specific arguments do not relate to cartography, we posit that contentions over cartographic imaginaries are one means of such diasporic governance and transnational projection of power.

Our argument in this paper thus connects significant current concerns in IR as they relate to critiques of imperial cartography, the impact of new rising powers on global order dynamics, and transnational governance of the diaspora. We push these lines of enquiry in novel directions by taking up how non-Western rising powers, with varied regime types including democratic and authoritarian states, use cartographic imaginaries concerning Kashmir and Taiwan. As our contribution to epistemological decolonisation, we deliberately theorise from non-Western sites, rather than viewing them simply as arenas for the ‘application’ of Eurocentric theory. By bringing together these two regional cases in IR for the first time, we show how the construction and control of cartographic imaginaries amount to an exercise of ideational power; in the next sections, for both cases, we highlight systematic and significant analytical dynamics in relation to representation, nationalism, and diaspora.

Construction and control of cartographic imaginaries: Kashmir

Notwithstanding the well-recognised internationally disputed status of Kashmir,Footnote 42 it is referred to as an ‘integral part of India’ ad nauseam. The territoryFootnote 43 often referred to as Kashmir encompasses a complex patchwork of regions oriented through historical trade relations and routes toward Central Asia, which have witnessed multiple and overlapping colonisations over several centuries and combined religious and cultural influences from Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam. In 1947, when India and Pakistan were formed after the end of colonial rule, the status of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) was unsettled, and the first war over the region between the two new post-colonial countries resulted in the matter being taken to the United Nations (UN) and a ceasefire line being established. This line, aptly termed the Line of Control (LoC), divided the region into Indian- and Pakistani- Administered Kashmir (IAK and PAK). Although intended as a temporary measure until a plebiscite mandated by the UN would be carried out to ascertain the Kashmiri people’s wishes, it became a permanent feature of life as the plebiscite was never carried out. The region has been the site of several wars since and continues to be a nuclear flashpoint. Neither side has had any administrative control over the line for over 75 years since then.

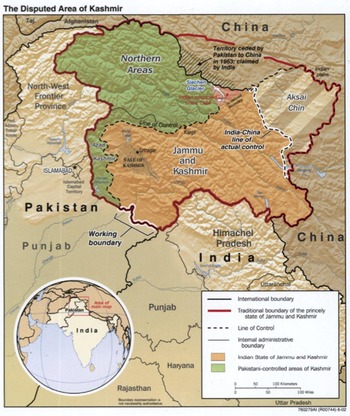

The existence of the dotted LoC on any accurate political map of South Asia is undeniable. Yet no Indian map of India or any international map of India in India shows the LoC. In terms of representation, the disputed region is not allowed to be depicted on the map as per correct international legal norms. Compare Figure 1 of the standard Indian Survey’s map of the region, for instance, with Figure 2 of the Library of Congress map of the region (which shows the correct boundaries of the disputed region in bold, and the dotted line of control that runs through it on the left side).

Figure 1. Map of Kashmir by the Survey of India.

Figure 2. Map of Kashmir by the Library of Congress, depicting the Line of Control (LoC) and disputed areas.

The dissemination of, and control over, maps is at the heart of the matter, because maps, including those on stamps, have often been used as a ‘subtle form of propaganda, especially in spreading knowledge world-wide of territorial claims’.Footnote 44 Dudley Stamp refers to vagaries of philatelic cartography in the historical context of the Indo-Pakistan problem over Kashmir (with a Hindu ruling class), which India claimed as an integral part of India, even as Pakistani claims were based on a Muslim majority among the people over much of the area. He writes, ‘the de facto boundary in Kashmir is the ceasefire line of 1948’, but India will not allow the importation of any book including maps which shows or suggests that Kashmir is not a part of India.Footnote 45 In 1957, India issued postage stamps to commemorate the change of currency to the rupee and ‘a major objective was to affirm in no uncertain terms the Indian claim to Kashmir’,Footnote 46 as the example of the 6 Naya Paisa (N.P.) stamp in Figure 3 shows. This image of the map on the postage stamp has been annotated by Stamp in Figure 4, and it makes clear how the map annexed all of Bhutan and excluded India’s territorial claims in the north-east but included ‘the whole of Kashmir on these maps as Indian, ignoring the Pakistani-occupied portion up to the ceasefire line of 1948 as well as the Tibetan area disputed with China’.Footnote 47

Figure 3. A 1957 stamp from India depicting a map of the country with the main rivers.

Figure 4. An annotated version of the map on the 6 N.P. Indian stamp from 1957 that shows all of Kashmir inside India; the annotations mark the inclusions and exclusions on the map, as well as pointing out the ‘cease-fire line’ (the LoC).

Erskine refers to the deceptions of cartography and the real repercussions they may have in the context of the 2015 official survey map of India that explicitly claimed the entirety of J&K as controlled by India, while Pakistan’s official map labelled it as disputed territory, although with suggestive colouring.Footnote 48 Snedden points out the many inaccurate depictions lacking historical support in the maps issued from the Government of India’s Press Information Bureau (PIB) in 2019 that entirely deny the existence of Pakistan-administered ‘Azad’ Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan and Chinese-controlled Aksai Chin and Shaksgam; these maps do not use terms such as Pakistan-occupied Kashmir or China-occupied Kashmir, let alone the Line of Control, thus creating two new Indian territories, ‘even though Indians have never set foot in the Pakistan- or Chinese-controlled parts’.Footnote 49 In 2020, Pakistan also reacted with its new maps claiming the region, which was widely-described in India as a ‘cartographic aggression’.

Indian scholars supportive of the government assessed possible responses to this action. For instance, Nanda and Alam concluded that a military response to such ‘cartographic aggression’ carried out by a ‘weaker state’ was not merited, and a ‘counter cartographic aggression’ may ‘draw unnecessary international attention on the India–Pakistan dispute [and] may not serve India’s interests’.Footnote 50 Therefore, they suggested that India ought to denounce this ‘cartographic aggression’ in strong diplomatic terms and block the dissemination of the new map. But, since the internet makes this difficult, they commended the Government of India for already blocking the website of the Survey of Pakistan. They emphasised that:

the most important step should be to stop the production and circulation of the new map. India needs to ensure that other countries and global institutions (e.g., the UN and its affiliate organs, the World Bank, IMF, etc.), print and electronic news agencies, publication houses, the International Cartographic Association, the World Meteorological Organization, and other inter-governmental organizations do not produce and publish maps of the world, Asia, South Asia, India and Pakistan reflecting the position of Pakistan.Footnote 51

Beyond depicting territory, cartographic imaginaries of the region are inextricably bound up with political claims-making about the region in line with nationalist representations of how the regions depicted by the maps ought to be read. The politics of mapping and counter-mapping by India and Pakistan (so-called cartographic aggressions) also involve other kinds of related representations. For instance, in 2018, a set of stamps was issued by Pakistan Post with 20 different images of ‘atrocities in Indian occupied Kashmir’ (‘including images of victims of alleged chemical weapons, pellet guns, “fake police encounters” and “braid chopping”, scenes of general abuse and pictures of Kashmiri protests’),Footnote 52 leading to a cancellation of carefully planned diplomatic talks between the two countries on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly. In both countries, the semiotics and semantics have intensified over time, as have clear guidelines only to use country’s Survey political maps or face fines and imprisonment. While a 1960 commemorative stamp in Pakistan showed a Pakistani map, with Kashmir shown in a different colour alongside the text: ‘Jammu & Kashmir; Final Status Not Yet Determined’, one of the 2018 stamps read ‘Kashmir will become Pakistan’.Footnote 53 Likewise, ‘Taking back Pakistan-occupied-Kashmir (POK)’ has been a theme in Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-ruled India, and in 2019, Amit Shah, the Indian home minister, told the parliament: ‘When I say Jammu and Kashmir, I include Pakistan-occupied-Kashmir and Aksai Chin.’Footnote 54 In 2015, the television channel Al Jazeera was taken off air in India for five days because ‘it had shown wrong maps of Kashmir’.Footnote 55 Al Jazeera programmes in India were replaced by a sign saying that the channel would not be available ‘as instructed by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting’, since Indian officials accused the Qatar-based broadcaster of ‘cartographic aggression’.Footnote 56

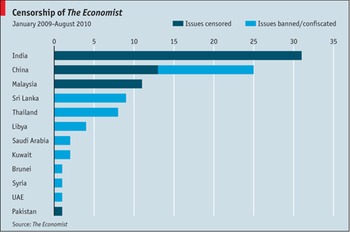

An especially noteworthy example of targeted censorship over depictions of Kashmir is provided by the treatment of the well-known magazine The Economist. In September 2010, The Economist reported that since January 2009, the publication has been banned or censored in 12 of the 190 or so countries in which it is sold, with newsstand copies particularly at risk (Figure 5).Footnote 57 Among the many examples (which include China blacking out maps of Taiwan), India was listed at the top of the list of censors, where ‘illegal’ was stamped on maps of Kashmir because of a depiction of the borders.

Figure 5. Graphic depicting the number of issues of The Economist that have been censored and banned.

In May 2011, the BBC reported that The Economist had accused India of ‘hostile censorship after being forced by the country’s authorities to cover up a map in its latest edition’.Footnote 58 The map depicted the disputed region of Kashmir as divided between Pakistan, India, and China. Tens of thousands of copies of the publication were distributed with a blank white sticker placed over a map of Kashmir, since ‘the map did not show all of Kashmir as being part of India’.Footnote 59 The BBC report added that ‘the authorities in India routinely target the international media, including the BBC, on the issue of Kashmir’s borders if the media do not reflect India’s claims’.Footnote 60 In a 2012 book review in The Economist, we again find a mention that ‘India’s government still tries to use maps to assert control over territory. It is so sensitive about maps that illustrate the line dividing Indian and Pakistani Kashmir – the de facto border – that it censors copies of the Economist containing them’.Footnote 61 In February 2012, The Economist carried a feature titled ‘Fantasy frontiers’ with an explainer on disputed borders in South Asia as a symptom of tensions between big neighbours, printing the maps with the territorial claims of India, Pakistan, and China, alongside a fourth clear depiction of current boundaries as shown in Figure 6:

Figure 6. The Economist depicting Indian, Pakistani, and Chinese border disputes.

In 2016, The Economist provided global data on boundary walls and fences worldwide since the fall of the Berlin Wall, stating that in Asia, walls and fences have generally proliferated to prevent illicit movement of people and goods, rather than to seal disputed borders, ‘though Kashmir’s line of control at India and Pakistan’s disputed northern boundary remains a highly-militarised example’.Footnote 62

In May 2016, The Washington Post carried an article titled ‘Cartographers beware: India warns of $15 million fine for maps it doesn’t like’.Footnote 63 It was referring to the Geospatial Information Regulation Bill 2016, which would make any unapproved representation of India’s map an offence punishable by up to 15 million US dollars and 7 years in prison;Footnote 64 ‘particularly contentious aspects of the GIRB included stiff fines and jail-time for individuals and companies that wrongly depicted India’s map (read: Kashmir)’.Footnote 65 The first line of The Washington Post story went thus ‘Let’s start with a basic fact: India claims much more land than it controls,’ adding that if this bill became law, ‘it would certainly complicate the operations of technology companies that rely on maps, such as Google and Uber’.Footnote 66 Indeed, this proposed legislation required ‘general or special permission from a security vetting authority before geospatial information may be acquired, disseminated, published or distributed’.Footnote 67 The Economic Times summarised: ‘Basically use of the map of India would require government permission first.’Footnote 68 The bill faced criticism from those in India who agreed with its intent – ‘Gross misrepresentation of India’s international boundaries not only by some of our immediate neighbouring countries but also by a few powerful media houses, intelligence agencies of other countries, as well as by some world organisations’ – but worried about its impact in terms of bureaucratic red-tape-ism on Earth Sciences academics in India.Footnote 69 It was shelved, but the deterrent effect of this proposed legislation was directed towards international firms, and sure enough, within a couple of days, Google altered its maps to suit India’s preferences, removing the dotted lines signifying that the region is disputed.Footnote 70

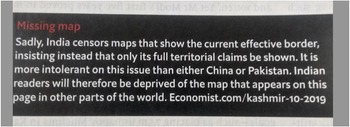

The Economist too has resorted to different tactics since, replacing the map with text or other workarounds. In 2019, when India and Pakistan were engaged in cross-border aerial skirmishes, The Economist article titled ‘On perilous ground’ in its Indian version featured a black patch with a text note referring to the censorship on Kashmir by India. As shown in Figure 7, it stated that India censors do not allow the depiction of the current effective borders and ‘on this issue are more intolerant than either China or Pakistan’.

Figure 7. A textual explanation of India’s censorship of maps published by The Economist.

The critical Indian media watchdog News Laundry reported details of this censorship, asking the magazine about its decision to use the black patch in India instead of a map.Footnote 71 The South Asia bureau chief of The Economist said that doing otherwise would mean that the issues would be confiscated or banned, and that the practice is ‘quite expensive’. The News Laundry report carried images from 2 March 2019 issue of The Economist but put a red patch over where the map might have been, stating ‘The March 2, 2019, edition of The Economist without the black sticker shows the Indian territory without Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir. NL can’t show it since we risk being penalised for it.’Footnote 72

While the censorship of Kashmir maps in The Economist goes back decades, there has been a change in its modality. In the 1970s and 80s, there would be rubber-stamping with the text ‘The external boundaries of India as depicted are neither correct nor authentic’. However, since 2011, there has been a switch from stamps to a sticker regime; a former South Asia bureau chief of The Economist stated that ‘in 2011 there was a change of heart at Indian customs, to threaten that any map imported to India that did not conform to the official position would contravene the law. Instead of agreeing to stamp each issue, as before, the customs officials threatened to imprison those who import(ed) such maps.’Footnote 73 A workaround used by the magazine now is to put a text bubble or a logo over the region of Kashmir in any map depiction to avoid having to depict the borders at all. The News Laundry report reflected that, with national security agendas ascendant in India and nationalism driving politics, the chances of censorship being overcome were bleak.Footnote 74 It is significant to observe that the changes in 2011 follow on from the summer of intense unrest in Kashmir in the summer of 2010, when over 100 youths lost their lives – ‘the year of killing youth’ as a Kashmiri journalist put it – at the hands of the Indian security forces.Footnote 75

Constructing the cartographic imaginary of Kashmir for Indians has been tied to its perception as far back as the creation of independent post-colonial India, through the narrative of ‘unity in diversity’. From the very outset, this region has been viewed as a ‘special’ place, imbued with a sacrality. Alongside the exhortation to ‘uplift’ the Kashmiri ‘race’ by triangulation and colonisation in the imperial era,Footnote 76 there is a tradition of spiritual-mystic realisations. The nineteenth-century imperial explorer and surveyor was also a sentimental geographer who finds something of himself in the frontier mountains as he seeks to fill the white spaces on the map; a figure no less than Younghusband refers to his experiences during his mission to the Kashmir region and beyond as those that went beyond the eye to the very soul.Footnote 77

In Indian nationalist cartographic imaginaries, Kashmir is key to depictions because it is a ‘lack’ that is also simultaneously always already ‘integral’ to India. The region has been a long-standing rallying cry for the Indian Right that allied with the Hindu minority of the region. The website of the ruling BJP in India commemorates Dr Shyama Prasad Mookerjee – who founded BJP’s forerunner party on the advice of the RSS, a nationwide far-right paramilitary founded in 1925 to protect India’s Hindu identity – as a ‘martyr’ for ‘the cause of integrating Kashmir with the rest of India’.Footnote 78 His slogan ‘Ek desh mein do Vidhan, do Pradhan aur Do Nishan nahi chalenge’ (two constitutions, two prime ministers, and two symbols cannot be allowed in one country) directly challenged the Article 370 autonomy provisions for the region in the Indian constitution, which were removed unilaterally by the Modi-led BJP in 2019.Footnote 79

There is substantive existing academic work on the history and politics of Kashmir in social sciences, but the narrative and visual depictions of Kashmir in textbooks do not acknowledge any of it. Textbooks often adopt a narrative that presents the ‘outsider’ Mughals as invaders who caused conversions to Islam in the region. The entire post-colonial period is ignored from the point of view of human rights or political dispute or viewed exhaustively as a reaction to Pakistani cross-border terrorist infiltration. Standard tropes define the study of Kashmir; Karmakar,Footnote 80 in his conversation with the Kashmiri scholar Nyla Ali Khan, states: ‘In the Indian standard curriculum, Kashmir with its unique history finds no proper place … students are not exposed to the nuanced history of Kashmir. We are more than often trapped in a biased idea of Kashmir as a “Heaven on Earth” turned into a “Valley of death” due to the terrorist intrusion.’ Khan agrees: ‘students in mainland India are exposed to official history … taught to look at Kashmir through the lens of national security or through the lens of religion’.Footnote 81 As Joshi mentions in his comparative examination of textbooks in India and Pakistan, top-down centralised curricula fundamentally define knowledge about the nation and its cartographic anxieties by presenting imagined versions of history and geography.Footnote 82 Kashmir, with its contested and syncretic history is, then, a key point of cleavage in the construction of such nationalist geography, and this results in an invention of its ‘natural’ cartographic belonging in India, and an emphasised Islamic affinity in Pakistan. The refrain ‘Kashmir is an integral part of India’ is constructed and controlled by the state, civil society, and the average citizen, especially in post-2014 India.Footnote 83

In May 2024, the University Grants Commission (UGC) – apex statutory body under the Government of India’s Ministry of Education that coordinates, determines, and maintains standards of higher education in India, provides recognition to universities in India, and disburses funds to recognised institutions – issued a Notice to all higher education institutions in the country that they are required to comply with sub-section (2) of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1990 as shown in Figure 8. It states: ‘whosoever publishes a map of India, which is not in conformity with the maps of India as published by Survey of India, shall be punishable with imprisonment which may extend to six months, or with fine, or with both’.Footnote 84

Figure 8. Notice circulated by India’s University Grants Commission (UGC) to higher education institutions regarding compliance with the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1990.

As a ‘crown jewel’ of India, depictions of Kashmir can further be understood through critical cartography analyses of other landscapes of feminised desire.Footnote 85 For the secular political formations, Kashmir has been affectively constructed as a symbol of India’s ‘unity in diversity’ and as a feminised place of unparalleled beauty. Kaul’s feminist analysis of Kashmir shows how the territory is feminised in the Indian imagination, alongside a discourse of possession and control by the masculinist Indian state, which often explicitly refers to the region in terms of a mistress acting petulantly, or a marital relationship gone sour.Footnote 86 There was even a specific desire for ‘fair-skinned Kashmiri women’ that was publicly articulated in India after the removal of Kashmir’s autonomy in the name of development, which combined patriarchal silencing of the subjugated with a gendered fantasy of liberating oppressed Kashmiri women and minorities.Footnote 87 If Kashmir’s geography is the lure of and desire for the female beloved, its place in the Indian ‘motherland’ (‘Bharat Mata’) is as the ‘head’ of Mother India’s geo-body.Footnote 88 In typical images such as in Figure 9, a sari-clad woman, holding a flag, is superimposed on the map of India.

Figure 9. An image of Mother India (‘Bharat Mata’).

The cartographic imaginaries work in the affective nationalist register to elicit a patriotic response from the citizen-beholder. The political effect of this map is that, as Kaul explains, a position on Kashmir that acknowledges the de facto status of Kashmir is akin to opting for a ‘beheading’ of Mother India.Footnote 89 Any suggestion of a complex political history of Kashmir’s relationship to India beyond the ‘integral part’ rhetoric is instantly seen as seditious, anti-national, and deserving of punishment, since a patriot must protect the life and honour of the Mother.

The construction of Indian cartographic imaginaries of Kashmir irrevocably implicate the media – not just the state-centric news media but also the curation of popular culture. Bollywood films have always had a ‘special’ place for Kashmiris.Footnote 90 In the last decade, a newer kind of cinematic representation has focused on rewriting the longer history of the region to present it as a quintessentially Hindu cradle of civilisation from millennia ago; a place of Indic learning where Sanskrit tomes were composed by erudite scholars. In such films, the communal-sectarian-religious divides between Kashmiri Pandits/Hindus (KPs) and Kashmiri Muslims, profitable politically to the Indian majoritarian nationalism, are exploited. As shown in Figures 10 and 11, the map of Kashmir in saffron (a colour with the popular connotation of Hindutva, or far-right Hindu nationalism, in India) serves as the backdrop in an archetypal 2022 film titled The Kashmir Files.

Figure 10. Image from the promotion of Vivek Agnihotri’s film The Kashmir Files.

Figure 11. Image from the promotion of Vivek Agnihotri’s film The Kashmir Files.

The Kashmir Files was wildly successful in evoking an affective response from the public; it was systematically promoted by the ruling BJP and also allied with BJP’s exclusive focus on the suffering of Kashmir’s Hindu minority. The film was endorsed publicly by BJP members including Prime Minister Modi and Home Minister Shah but castigated by the International Film Festival of India (IFFI) jury head, the critical Israeli film maker Nadav Lapid, as a ‘propaganda, vulgar movie’ that presents KPs as the ‘real’ and authentic inhabitants of the region, whose victimisation by the militants is given prominence while the military treatment of Kashmiri Muslims is entirely erased.Footnote 91 This film confirmed that nationalist constructions of the region were paramount, and ‘only certain kinds of cultural productions/texts/-novels/-films on Kashmir are, and can be, widely read/seen in contemporary India’.Footnote 92 The arch-villain in the film Kashmir Files is a female JNU professor reflecting a composite of actual Indian female public intellectuals like Professor Nivedita Menon at JNU (referred to in the introduction here) and the writer and activist Arundhati Roy, both of whom have faced the colonial-era charges of ‘sedition’ for public speech on Kashmir.

A key mechanism of punitive control for cartographic imaginaries in Indian public discourse is the targeting of those in academia, civil society, or activism who speak the historical facts on Kashmir as ‘anti-national’ and ‘seditious’.Footnote 93 This framing of the seditious ‘anti-national’ is pervasive in Indian media and effective in regulating and controlling the permissible imaginaries of Kashmir,Footnote 94 as it operates in combination with coercive measures to co-opt favourable media coverage for the BJP.Footnote 95 The ‘anti-nationals’ are accused of acting as foreign agents at the behest of Pakistan or the West; as ‘brown sepoys of the Western colonial masters’.Footnote 96 In 2024, the Indian criminal justice system was overhauled via profound changes introduced through legislation passed in 2023 at a time when over 146 MPs were suspended from parliament owing to their demands for Prime Minister Modi to address inter-ethnic and sexual violence in the north-eastern state of Manipur. Following the calls to rename ‘India’ as ‘Bharat’,Footnote 97 the Indian Penal Code was renamed the ‘Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita’ (BNS), and numerous changes were introduced with effect from 1 July 2024, most contentious of which are extending the maximum duration of police custody, discretionary prosecution, expanded definition of terrorism (including acts that ‘disturb public order’ or ‘destabilize the country’), removal of legal aid provision, and vaguely defined offences, including ‘acts endangering sovereignty’.Footnote 98 On Kashmir, any critical representation/text risks these charges.

In addition to structuring and circulating the cartographic imaginary of Kashmir through nationalist historical narratives at the discursive level, as well as in territorial maps within Indian textbooks at the cartographic level, it has been exported, projected, and controlled internationally through overseas diaspora communities and punitive pursuit of economic and legal means. The film Mission Impossible: Fallout, starring Tom Cruise and the sixth in the series, is meant to be set in Kashmir, but it was denied permission to shoot in India.Footnote 99 Indian viewers cannot hear or see the word Kashmir in the film, because India’s Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) asked the film’s makers to ‘remove or rectify’ a location title identifying one of the shooting locations as ‘India-controlled Kashmir’ and to also get rid of the map that the board claimed ‘misrepresented’ the boundaries of J&K state.Footnote 100 The CBFC chief added: ‘Integrity of our country’s borders are non-negotiable and cannot be compromised on for the sake of entertainment.’Footnote 101 Further, the Information and Broadcasting Ministry raised objections to ‘wrongful depiction of J&K’s boundaries in a map shown in Tom Cruise-starrer Mission: Impossible – Fallout’, asking the MEA (Ministry of External Affairs) to intervene because the cuts in the Indian version of the movie do not apply to its global version (see Figure 12).Footnote 102

Figure 12. Illustration by The Print.

After the election of the US president Joe Biden in 2020, a BBC World Service video broadcast from London carried a programme on what countries around the world want from Joe Biden, in which it showed a map of India highlighted in red which missed out the disputed regions. A British MP of Indian origin, representing a constituency in West London with a significant Indian diaspora, formally complained to the director general of the BBC, calling this depiction ‘deeply insulting’.Footnote 103 His letter further stated that the ‘map shows an incomplete India, it does not highlight Jammu and Kashmir which is recognised as a core and integral part of India. To represent Jammu and Kashmir as anything less than Indian is deeply insulting to millions of Indians living here in the UK and in India’; he suggested such a depiction affected the soft power of the UK because BBC World Service would be ‘perceived as partisan and “anti-India” as is currently being asserted online’.Footnote 104 Many in the Indian diaspora in the UK were strident in his support, demanding immediate action. The BBC apologised and updated its broadcast stating that: ‘From London we mistakenly published a map of India online which contained inaccuracies … We apologise for any offence caused.’Footnote 105

In 2015, the Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg shared a post about Facebook that showed India’s map ‘incompletely’, and he was subjected to a furious response from numerous Indians, who called for a ban on Facebook, with comments such as ‘all Indians log off Facebook if map is not corrected’.Footnote 106 Forbes reported that at the time India was a key market, with over 112 million Facebook users and potentially millions more; Zuckerberg deleted his post. Google’s mapmakers have also had a long history of map-related disputes with Indian authorities. In 2014, the Survey of India filed a police complaint against Google regarding the depiction of India’s national boundary, following on from which Google shows different/altered maps of India on the basis of user location.Footnote 107

The Indian diaspora has been an important factor in normalising the ascendance of Hindu majoritarian nationalism Hindutva in India,Footnote 108 and in turn, there has been a systematic Indian effort at harnessing the diaspora during Modi’s rule.Footnote 109 A certain civilisational idea of India as a primordial ‘Bharat’,Footnote 110 in fact, even an ‘Akhand Bharat’ (undivided India) that extends over and across neighbouring sovereign countries,Footnote 111 is increasingly normalised. The diaspora, large sections of which have avidly supported Modi, plays an important role in engendering the common sense of the Indian cartographic imaginary on Kashmir. As Kaul and Menon point out, India is a leading country of origin of international migrants, and while traditional studies of the Indian diaspora emphasised its heterogeneity and its experience of marginalisation and ethnic discrimination in the West, in the post-2014 period of Hindutva India under the Modi-led BJP, the Indian diaspora has been demonstrative of an activist agency in repurposing the idea of India for Western societiesFootnote 112 (as an example, consider the diaspora celebration of the controversial Ram Temple in India).Footnote 113 There has been a strong state focus on strengthening the emotional connexion with India for the diaspora, and policy relaxations for the pursuit of overseas investment by the diaspora. This long-distance Hindutva nationalism has sought to make India synonymous with the Hindutva idea of India. In recent decades, a key role has been played by organisations such as the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), Hindu Forum of Britain, Hindu Human Rights, Hindu Students Council, and the National Hindu Students Forum (NHSF), who have focused on activities directed at youth or on university campuses overseas. Hindutva activism in the diaspora has also pursued technological means such as setting up E-shakhas or electronic shakhas (a shakha is a term often used for in-person gatherings of RSS). The BJP IT Cell (Information Technology Cell) was founded in 2007,Footnote 114 and it pushes coordinated online attacks, which are gendered and Islamophobic and increasingly disguise regressive nativism as anti-colonial revenge, on any criticism of Hindutva, BJP, or Modi. They are ferociously sensitive to statements and depictions of Kashmir.

Although India does not allow dual citizenship, the category of Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) was created in 2005 to bring the diaspora closer to its country of origin.Footnote 115 In recent years, it has become ever more evident that the diaspora is expected to export a specific and definitive idea of the country, and Kashmir is a key part of this. In September 2019, the Press Information Bureau (PIB) of the Government of India put out a message from the Indian Vice President’s Secretariat calling upon the Indian diaspora to ‘effectively counter false propaganda and negative narrative about India, particularly in the wake of the [then] recent reorganization of the Jammu and Kashmir State’.Footnote 116 The release goes on to say that ‘overseas Indians must create awareness in the countries of their stay that the dilution of Article 370 was purely an internal administrative measure and aimed at accelerating the development of Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh’.Footnote 117 It also mentioned that there are ‘vested interests’ in Western media that portray a ‘negative image’ and ‘spin fictitious narratives’ that intolerance, religious, and social disharmony are on the rise in the country and called upon the diaspora to ‘effectively counter such falsehoods and project the correct image of India’.Footnote 118 Increasingly, there have been instances where academics, journalists, and others who hold an OCI are denied permission to enter the country and are deported, depriving them of access to work or family in India.Footnote 119 In the 2024 case of the deportation of a Kashmiri Pandit British OCI-holding academic, no reasons were given by the government for refusing entry, but news channels in India mentioned that, per government sources, it was due to her critical academic work on India, and the use of the UN-compliant terminology ‘Indian administered Kashmir’ for the region.Footnote 120

Construction and control of cartographic imaginaries: Taiwan

In its entire history, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has never controlled Taiwan. Taiwan’s history is chequered with global colonisation efforts by imperial powers such as the Dutch, Spanish, Japanese, and arguably the Kuomintang (KMT). Yet the foundation of the modern Taiwanese state is undeniably intertwined with that of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). When the KMT lost China to the Communists in the aftermath of the Chinese Civil War and War of Resistance against Japan, they retreated to Taiwan and rebuilt the Republic of China (ROC) government there with the intention of regaining control of the mainland. At the same time, the CCP sought to ‘liberate’ Taiwan and integrate it into the then newly formed PRC. However, neither the CCP nor KMT realised their respective territorial ambitions. Since the UN passed Resolution 2758 in 1971 indicating that only one state could represent ‘China’, Taiwan has experienced marginalisation within the international community and exclusion from most international organisations, as well as losing most of its diplomatic allies to the PRC under the ‘One China’ policy.

Despite these apparent challenges to its statehood, Taiwan has operated as a de facto state for several decades. Taiwan has a permanent population of approximately 23 million people, defined territorial bounds, a democratically elected government, and the capacity to conduct relations with other states through its embassies and representative offices overseas. Based on these four categories set out by the 1933 Montevideo Convention, Taiwan meets the criteria for statehood.Footnote 121 Furthermore, by adopting a declarative understanding of statehood – which evaluates statehood based on effectiveness rather than legitimacy or recognitionFootnote 122 – the case for Taiwan’s statehood is strengthened.Footnote 123 In addition to the four criteria laid out by the Convention, Taiwan has a robust and dynamic civil society, its own military, and diplomatic relationships (both formal and informal) with other states. A majority of Taiwanese people also identify as ‘Taiwanese’ as opposed to ‘Taiwanese and Chinese’ or ‘Chinese’.Footnote 124 Despite these clear indicators of a statehood that is separate from China, the notion of Taiwan as a Chinese province looms large within Chinese society. This idea is constructed through official discourse and education practices, and it is sharply regulated by Chinese state institutions, both domestically and internationally. This is due to a number of interlinking factors. First, the CCP is committed to implementing unification with Taiwan one day and has not renounced the use of force in achieving this end. Second and relatedly, the CCP sees unification with Taiwan as resolving a historical issue rooted in its conflict with the KMT during the Chinese Civil War, which arguably has never ended. Third, the Chinese state seeks to shape the global environment in ways that facilitate its goal of unification with Taiwan. For these reasons, cartographic representations of Taiwan are one of many terrains upon which the Chinese state exercises its productive power and imperial ambitions on an increasingly global scale.

Akin to Kashmir, stamps have historically played a role in constructing and reinforcing the cartographic imaginary of Taiwan as conceptualised by the CCP. Figure 13 shows a 1968 stamp depicting a red map of the PRC with the outline of Taiwan not yet shaded in red. This indicates on the one hand that Taiwan has yet to join the Communist PRC while also making clear the CCP’s intention to take Taiwan in the future. The slogan on the red map of the PRC reads ‘The entire nation (mountains and rivers) is red’ (quanguo shanhe yi pian hong 全国山河一片红). The stamp was designed to commemorate 29 revolutionary committees of the PRC’s autonomous regions, implying that one day Taiwan will be one such region.Footnote 125 Compare this to Figure 14, a stamp printed in 1977, which reads ‘Meet the new wave of the Chinese revolution’, commemorating the 30th anniversary of the 28 February 1947 (known as ‘228’) uprising in Taiwan against the KMT. The reference to the 228 massacre seeks to position the CCP as the revolutionary vanguard of the Taiwanese people, declaring ‘We [the CCP] will liberate Taiwan [from the KMT]!’ Both stamps illustrate how Taiwan has historically been depicted by the CCP as a ‘breakaway’ province that will eventually be liberated and brought into the Communist fold through unification with the PRC. In keeping with the political and ideological evolution of the Chinese party-state over the past several decades, the official discourse on Taiwan has shifted away from an idea of leading a proletarian revolution to one of achieving unification. This unification is envisioned within the broader projects of ‘national rejuvenation’ and realising the ‘China dream’. This is evident in Xi Jinping’s speeches, which seek to bolster the illusion that unification with Taiwan is inevitable and a seemingly natural outcome of China and Taiwan’s shared history. Take for example Xi’s 2022 speech in which he stated: ‘The historical wheels of reunification and national rejuvenation are rolling forward.’Footnote 126 While the undertones of this rhetoric have become less overtly Communist and more nationalistic, the cartographic imaginary of Taiwan has nevertheless been consistently associated with unification, territorial integrity, and the completion of the Chinese nation.

Figure 13. A 1968 stamp depicting a red map of the PRC with the slogan ‘the entire nation (mountains and rivers) is red’ and the outline of Taiwan not yet shaded in red.

Figure 14. Two stamps printed in 1977 commemorating the 30th anniversary of the ‘228’ uprising in Taiwan.

Like depictions of Kashmir as the ‘crown jewel’ of India, Taiwan is commonly referred to as a ‘precious island’ or baodao (宝岛), ‘bao’ literally meaning ‘treasure’ or ‘precious stone’. Discursive associations between the island and the imagined body of the Chinese nation are evident in the way Chinese officials often call Taiwanese people ‘compatriots’ or tongbao (同胞), which means ‘of the same breast’. Chinese discourse also tends to emphasise the shared ethnicity of Chinese and Taiwanese people by grouping Chinese and Taiwanese under the ‘Han’ ethnic category (hanzu 汉族), as well as describing the cross-Strait situation as ‘one family on both sides of the Strait’ (liang an yi jia ren 兩岸一家人). This sense of shared ancestry and familial bonds underpins a common nationalistic rhetoric of China’s ‘5,000-year history’, which evokes narratives of the Chinese empire as a cultural and economic power in the Asia.Footnote 127 Those seen as supporting Taiwanese independence and opposing unification are often branded within Chinese official discourse as ‘secessionists’ (fenlie fenzi 分裂分子) seeking to break apart the ‘ancestral land’ (zuguo 祖国). Although Chinese state discourses about Taiwan engage less in exoticisation and fetishisation of the region and its peoples, they are nevertheless imbued with historical entitlement and paternalism, something shared with certain Indian positions on Kashmir. Chinese official discourses stress shared ethnicity, ancestry, and heritage to lend a sense of China’s historical entitlement to unification with Taiwan – thus seeking to naturalise the goal of unification. This also casts China in a paternalistic role seeking to reunite a ‘broken’ family and to safeguard the ‘precious island’ against the pernicious influence of the West.

In terms of cartography, the idea of Taiwan as a province of China has been reinforced in the modern curriculum for Chinese senior high school students. The 2019 History Curriculum Standard in General High Schools (putong gaozhong lishi kecheng biaozhun 普通高中历史课程标准) and the Outline of Chinese and Foreign History (zhongwai lishi gangyao 中外历史纲要) contain maps of Taiwan and disputed territories such as the islands of Diaoyu/Senkaku and the South China Sea as parts of China. These maps not only feature in domestic teaching materials but have also appeared in textbooks on Chinese culture used abroad. For example, the textbook Senior Chinese Course: Chinese Language, Culture and Society contains a map of China which encompasses Taiwan and the South China Sea, as Figure 15 shows. In total, 633 copies of the textbook were sold in Australia and were used across 11 Victorian schools for the Victorian Certificate of Education.Footnote 128

Figure 15. A map from the textbook Chinese Language, Culture and Society depicting the nine-dash line extending into the South China Sea and Taiwan as territories of china.

In its efforts to foster more favourable international conditions for unification, the Chinese state has systematically challenged, attacked, and censored any cartographic representations overseas which deviate from the state-sponsored cartographic imaginary. For example, several UK organisations received pressure from Chinese elites, customers, members, and institutions to alter the designation of Taiwan on digital drop-down menus from ‘Taiwan’ to ‘Taiwan, China’ or ‘Taiwan, Province of China’. The online campaign to change the designation of Taiwan to a territory of China across numerous UK websites was evident in the cases of British Airways,Footnote 129 Harry Potter’s Wizarding World,Footnote 130 the London School of Economics,Footnote 131 and the tech consortium The Open Group, as Figure 16 demonstrates.

Figure 16. A screenshot taken of the drop-down menu from The Open Group’s website.

This campaign not only affected UK organisations, but also those in the United States, Australia, and the world over. Overseas organisations, especially those with many Chinese customers, failing to comply with demands to designate Taiwan as part of China have faced economic pressures. For example, following a wave of backlash from Chinese netizens on Weibo, the retailer Gap issued an apology for selling a T-shirt depicting a map of China without including south Tibet, Taiwan, and the South China Sea, stating: ‘Gap Inc. respects the sovereignty and territorial integrity of China. We’ve learned that a Gap brand T-shirt sold in some overseas markets failed to reflect the correct map of China. We sincerely apologise for this unintentional error.’Footnote 132 Similarly, previews of Top Gun: Maverick were edited to remove patches of the Taiwanese and Japanese flags originally sewn onto Tom Cruise’s jacket, shown in Figure 17. It is alleged these alterations were made to appease the Chinese company Tencent (TCEHY) Pictures, which was an investor but later pulled its financial backing.Footnote 133

Figure 17. A scene from the uncensored version of Top Gun: Maverick showing the Taiwanese and Japanese flags sewn on Tom Cruise’s jacket.

These actions highlight the Chinese state’s transnational productive power through control over the depiction and interpretation of cartographic imaginaries of Taiwan. This form of control has been successfully asserted at two levels: first, overseas companies and organisations as well as their products and digital domains; and second, netizens relying on those digital domains to obtain knowledge and information. If the overseas organisations fail to comply with demands to designate Taiwan as a part of China, they potentially face boycott from Chinese customers, withdrawal of Chinese-linked investments, or punitive legal action. These represent forms of economic and legal warfare which have been frequently deployed in ‘correcting’ depictions of Chinese territory and Taiwan. They clearly illustrate how the Chinese state’s control over cartographic imaginaries seeks to naturalise a discourse and image of Taiwan as a territory or province of China. Over time, and if left unchallenged, these activities have the potential to establish the misleading belief among foreign publics that Taiwan is a territory of China.

This is not to suggest that China’s exercises of productive power through cartographic representations have not been met with opposition. Taiwan and other states involved in the South China Sea disputes have engaged in forms of counter-mapping as part of their resistance efforts. Rival historical claims to South China Sea islands cited by Beijing and Taipei capture this politics of mapping and counter-mapping all too well. On the one hand, the PRC has sought to incorporate vast tracts of maritime space through its mappings and historical claims over the South China Sea, while, on the other hand, Taiwan has sought to distance itself from its historical ties with China in framing its rival claims.Footnote 134 In a 2020 white paper, the Taiwanese government promoted a renewed emphasis on the history of Taiwan’s aboriginal peoples’ long-standing reliance on the sea and Taiwan’s ‘traditional maritime culture’.Footnote 135 This discourse recast Taipei’s maritime claims in a way that distanced Taiwan from China, a move condemned by Chinese state media outlets as another manifestation of Taiwanese independence.Footnote 136

Overseas and beyond the South China Sea, China’s long-standing efforts to control the cartographic imaginary of Taiwan have been informed by its nationalist education system, which arguably began with the 1992 Patriotic Education Campaign (PEC). The PEC was a set of educational reforms which sought to promote and strengthen national solidarity across Chinese society in the aftermath of Tiananmen in 1989. The PEC reforms introduced patriotic materials within the Chinese national curriculum including the ‘national conditions’ (guo qing 国情) series of readers and Never Forget National Humiliation (wuwang guochi 勿忘国耻). These educational materials advanced historical narratives of China’s victimisation, including loss of territorial control to colonial powers. This included the ceding of Taiwan to Japan following the defeat of Qing dynasty forces during the first Sino-Japanese War and the signing of the Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895. The unification of Taiwan with China was seen as a ‘critical element in the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”’ in the PEC.Footnote 137 The PEC was therefore key to the construction of the cartographic imaginary of Taiwan among the Chinese population, including diaspora who carry these beliefs and nationalistic sentiments abroad.

Many educational materials used in schools across the PRC are infused with discourses claiming Taiwan as a ‘borderland’ territory of China since the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).Footnote 138 Such narratives lend a sense of historical continuity to territorial claims on Taiwan stretching back to China’s dynastic period, when in reality Taiwan’s designation as a province of China under the Qing dynasty lasted only from 1887 to 1895.Footnote 139 These territorial claims are interwoven with narratives of China’s ‘struggles against foreign aggression’ to ‘save the nation’ during the late Qing dynasty and early years of the Republic of China government.Footnote 140 Therefore, the unification of Taiwan is deeply embedded in a broader post-colonial narrative, one which both portrays China as the once-powerless victim whose territory was carved up by foreign powers during the ‘Century of National Humiliation’ (bainian guochi 百年国耻), and by extension, creates a historical justification for China’s assertive actions against those foreign powers when it comes to defending ‘territorial sovereignty’, including its claims on Taiwan. The cartographic imaginary of Taiwan is therefore imbued with a sense of patriotic injustice towards the historical exploitation of China by colonial powers. This indicates the affective component of the cartographic imaginary at work, which undoubtedly plays a role in mobilising Chinese citizens domestically and overseas to ‘correct’ any cartographic representations of Taiwan that deviate from state-sponsored images and narratives.

In addition to forging a sense of historical continuity and creating narratives of national rejuvenation, the cartographic imaginary of Taiwan as a part of China has also been constructed within a master narrative of ‘pluralist unity’ (duoyuan yiti 多元一体), the ‘imagined process of gradual integration and unity among different ethnic groups’.Footnote 141 This pluralist unity narrative is pervasive in teaching materials and is applied to not only Taiwan but also Tibet, Inner Mongolia, and other disputed territories. Since the 1990s, young Chinese students have been taught that these territories have remained parts of China since dynastic rule. These pluralist unity discourses highlight the dissemination of nationalistic ideology within the Chinese education system.Footnote 142 This also illustrates another affective dimension of the Taiwan cartographic imaginary – it is not only a site through which feelings of Chinese patriotic injustice are aroused but also a site upon which a sense of national unity can be restored.

While the cartographic imaginary of Taiwan has been generated and disseminated through nationalistic historical narratives and maps within textbooks, it has also been exported, projected, and controlled internationally through overseas Chinese communities as well as punitive measures by the Chinese state in the forms of economic and legal warfare. Culture, which encompasses cartography, has therefore become a way in which the state asserts its sovereignty domestically and exercises productive power internationally.Footnote 143 This is not only due to the educational reforms enacted by the 1992 PEC, which saw generations of Chinese citizens educated with patriotic historical narratives of Taiwan as part of China, but also an expanded propaganda system (xuanjiao xitong 宣教系统) that has focused on cultivating relationships with the Chinese diaspora since the 1980s.Footnote 144 The system’s practice of ‘propaganda and thought work’ seeks to shape domestic and foreign public opinion on certain issues, including Taiwan.Footnote 145

The Taiwan Affairs Office (TAO), the CCP institution within the propaganda system responsible for state discourses about Taiwan, issues guidance on discussion of Taiwan to Chinese officials and media outlets at home and abroad.Footnote 146 The TAO’s ‘Suggestions on the correct terminology for Taiwan-related propaganda’ discourages officials, media outlets, and Chinese netizens reporting on Taiwan from referring to the ‘Taiwan government’ or using the terms ‘state’, ‘central’, or ‘national’. The TAO indicated that if such terms must be employed they should be prefaced with ‘so-called’ or use inverted commas around the term.Footnote 147 The guidance also encourages use of the designation ‘Taipei, China’ or ‘Taiwan, China’ when referring to international organisations, international and economic trade associations, and cultural and sporting organisations.Footnote 148 These discursive tactics naturally omit or altogether dismiss any terms which imply Taiwan’s status as a separate state, reinforcing the cartographic imaginary of Taiwan as part of China. The TAO’s guidelines demonstrate how the discursive construction of the cartographic imaginary of Taiwan as part of China is systematised and regulated not only domestically but also transnationally among overseas Chinese officials, institutions, and netizens.