Introduction

‘Farmers are probably the most adaptable group of people who work with the weather all year long, often time having more weather experience than the experts.’

—Farmer respondentFarmers are on the frontlines of climate change. Climate change exacerbates complex interactions between economic and management challenges that threaten the productivity and viability of farms. Small farmers, many of whom are also beginning farmers (defined by U.S. Department of Agriculture as those who have been farming for less than 10 yr), are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change because many of them lack the access to land and capital (U.S. Department of Agriculture), water for irrigation because many are junior water rights' holders (Li et al., Reference Li, Xu and Zhu2018) and to farm support programs designed for larger commodity producers (e.g., crop insurance) (Belasco et al., Reference Belasco, Galinato, Marsh, Miles and Wallace2013). In the Southern Willamette Valley, in western Oregon, small farmers produce a variety of fruits, vegetables, tree fruit, livestock and poultry for direct to consumer markets. The scale of these farms varies from less than an acre to more than a hundred acres. Willamette Valley small farmers grow and sell food locally and directly to consumers via farmers’ markets, CSAs, farm stands and other channels (Fery and Garrett, Reference Fery and Garrett2017).

The Northwest region is expected to experience higher temperatures, more variable precipitation and changes to the productivity of specific crops. It is expected that there will be earlier peak flows and less snowpack, limiting the water available for irrigation in the summer growing season (May et al., Reference May, Luce, Casola, Chang, Cuhaciyan, Dalton, Lowe, Morishima, Mote, Petersen, Roesch-McNally and York2018). Further, it is expected that the region will experience more extremes in precipitation from atmospheric rivers (heavy rainfall events) to drought conditions. To better serve the needs of small farmers, it is necessary to understand how they are thinking about climate risks and whether they intend on making changes in response (May et al., Reference May, Luce, Casola, Chang, Cuhaciyan, Dalton, Lowe, Morishima, Mote, Petersen, Roesch-McNally and York2018).

Unfortunately, very little data are available regarding farmers’ perspectives on these topics in the Northwest (Chatrchyan et al., Reference Chatrchyan, Erlebacher, Chaopricha, Chan, Tobin and Allred2017; Borelli et al., Reference Borelli, Roesch-McNally, Wulfhorst, Eigenbrode, Yorgey, Kruger, Bernacchi, Houston and Mahler2018; Roesch-McNally, Reference Roesch-McNally2018). To this end, the USDA Northwest Climate Hub partnered with the Oregon State University (OSU) Extension Small Farms Program to include questions related to climate change beliefs and attitudes toward adaptation in a larger study in the Southern Willamette Valley. The lessons learned from this short survey highlights climate risk perceptions, attitudes toward climate adaptation, climate change beliefs and use of climate-related tools and resources. These findings will be of interest to those working to ensure the economic viability and ecological sustainability of small farms in the era of global climate disruption.

Methods

An online Small Farms Needs Assessment survey (Fery and Garrett, Reference Fery and Garrett2017) was developed, piloted and disseminated to farmers, ranchers and landowners in the Southern Willamette Valley, with a focus on farmers from Linn, Benton and Lane counties, during the spring of 2017. During this time, notices about the survey were distributed via social media, electronic and printed newsletters, direct emails, press releases, flyers and handouts. The primary focus of the survey was to ask participants what they wanted the OSU Small Farms Program to work on over the coming years.

The overall survey garnered 249 responses. All survey respondents were asked if they were interested in providing their opinions regarding a series of climate change questions. Of the total number of respondents, 48% (n = 123) said yes and responded to the rest of the survey. Therefore, only those farmers who had at least some interest in climate change issues would have responded to this portion of the survey. For the purposes of this paper, we focus our analysis on those climate-related questions adapted from well-tested surveys conducted with farmers from other regions in the USA (Loy et al., Reference Loy, Hobbs, Arbuckle, Morton, Prokopy, Haigh, Knoot, Knutson, Mase, McGuire and Tyndall2013; Seamon et al., Reference Seamon, Roesch-McNally, McNamee, Roth, Wulfhorst, Eigenbrode and Daley Laursen2017). Specifically, we included a subset of questions that addressed farmers' attitudes toward adaptation, including their perspectives on the need for taking action, assessment of actions already taken, their beliefs about climate change and their use of tools and resources to aid in climate decision-making (see survey questions in Supplementary Materials).

In terms of the limitations of the study, the response of 249 is fairly low. According to the USDA 2012 Agricultural Census, for Linn, Benton and Lane counties that there are 5328 small farms (those farms grossing less than $250,000 yr−1). Further, given that this was a convenience sample of small farmers, some whom are already connected to OSU Extension networks, we expect that there would be some self-selection bias on behalf of respondents. Given that this survey was administered via a convenience sample, and no general demographic information was included, it is not recommended to generalize these results to the broader population of small farmers in the region or make comparisons to Agricultural Census data.

Results and discussion

Of those who agreed to answer the questions about climate change, the majority were from Linn, Benton and Lane counties (86%) (Table 1). Forty-seven per cent of the respondents identified themselves as a farmer/rancher, 34% as a landowner and 14% selected ‘other’. The ‘other’ category was open-ended and the majority self-identified as ‘hobby farmers’ or those hoping/planning to farm in the future. Respondents were able to select more than one role; therefore, all results from these respondents have been included in our analysis.

Table 1. Table of key farmer characteristics (n = 123)

a Respondents were able to choose more than one option.

A majority of respondents (65%) considered themselves beginning farmers. Nearly 50% farm on less than 10 acres and another 22% operate on more than 50 acres. Fifty-five per cent of respondents farm on land without water rights or with limited water rights, which is a real challenge for specialty crop producers who typically rely on irrigation. Respondent's farming operations were diversified, with the majority producing a combination of products with the top five being vegetables, tree fruits/nuts, pasture/forage/hay, herbs and poultry production for eggs.

Climate change beliefs and attitudes toward adaptation

In terms of climate change beliefs, the majority of respondents (70%) believe that climate change is occurring, and is caused mostly by human activities. The majority of respondents also agreed that action needs to be taken to minimize climate risk. These reported beliefs in climate change were higher than among similar studies of farmers conducted in other parts of the USA (Prokopy et al., Reference Prokopy, Morton, Arbuckle, Mase and Wilke2015; Chatrchyan et al., Reference Chatrchyan, Erlebacher, Chaopricha, Chan, Tobin and Allred2017). Additionally, previous research makes a connection between these climate beliefs and support for climate action (Howden et al., Reference Howden, Soussana, Tubiello, Chhetri, Dunlop and Meinke2007; Arbuckle et al., Reference Arbuckle, Prokopy, Haigh, Hobbs, Knoot, Knutson, Loy, Mase, McGuire, Morton and Tyndall2013; Hyland et al., Reference Hyland, Jones, Parkhill, Barnes and Williams2016; Chatrchyan et al., Reference Chatrchyan, Erlebacher, Chaopricha, Chan, Tobin and Allred2017) suggesting that as belief in anthropogenic climate change increases, so does support for adaptive and mitigative action, although this trend is not always supported in the literature (Schattman et al., Reference Schattman, Ernesto Méndez, Merrill and Zia2018a, Reference Schattman, Roesch-McNally, Wiener, Niles, Iovanna, Carey and Hollinger2018b).

The majority of the respondents (58%) strongly agreed with the statement that they will have to change practices to cope with increasing climate variability in order to ensure the long-term success of their operation. Fifty-two per cent of these respondents indicated that they have already taken action to respond to climate change on their farms. It is clear that farmers from other parts of the country are also beginning to take action in response to climate change (Jemison et al., Reference Jemison, Hall, Welcomer and Haskell2014; White et al., Reference White, Faulkner, Sims, Tucker and Weatherhogg2018; Schattman et al., Reference Schattman, Roesch-McNally, Wiener, Niles, Iovanna, Carey and Hollinger2018b) and many farmers anticipate taking action in response to projected changes (Haden et al., Reference Haden, Niles, Lubell, Perlman and Jackson2012; Niles et al., Reference Niles, Brown and Dynes2016; Roesch-McNally, Reference Roesch-McNally2018; Roesch-McNally et al., Reference Roesch-McNally, Benning, Wilke, Arbuckle, Morton, Lachapelle and Albrecht2019).

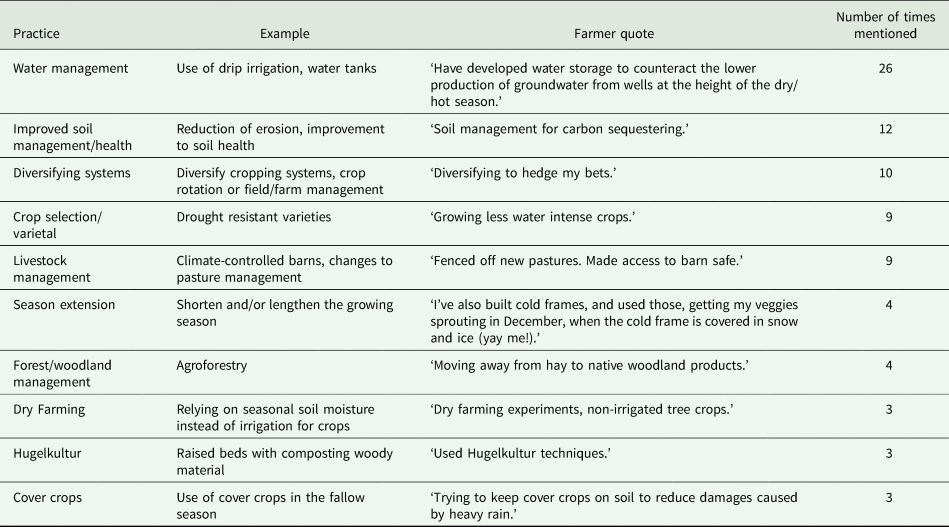

Among the farmers surveyed as part of this analysis, a subset of them responded to an open-ended question about the kinds of changes they had made as a result of climate change. These responses were then organized into thematic categories that best reflect the broad ideas representative in farmer's responses. The top five themes among farmer responses were changes to water management, improvement to soil management, diversifying crop/farm system, crop/varietal selection and livestock management (Table 2).

Table 2. Responses (n = 51) to an open-ended question about what changes farmers made as a result of changes in the climate

Multiple responses recorded for each respondent.

In terms of attitudes toward adaptation, most respondents suggested that action is necessary to respond to climate risks, with 71% disagreeing with the statement that there was too much uncertainty about the impacts of climate change to justify changing their practices and 78% agreeing or strongly agreeing that they should take additional steps to deal with increased weather variability (Fig. 1). This is in contrast to the same questions asked of Midwestern farmers who largely agreed that there was too much uncertainty to justify taking action (Morton et al., Reference Morton, Roesch-McNally and Wilke2017). However, only 32% of our respondents agreed with the statement that they have the knowledge and skills to deal with weather-related threats to their operation. This is similar to concerns of New England producers who are also worried that they lack financial capacity, knowledge and technical skills to deal with weather-related threats on their farms (White et al., Reference White, Faulkner, Sims, Tucker and Weatherhogg2018). In addition, 32% agreed or strongly agreed that they were concerned that available best management practice technologies are not effective enough to protect farms from climate impacts.

Fig. 1. Respondents (n = 123) were asked a series of agreement scale questions regarding their attitudes toward adaptation.

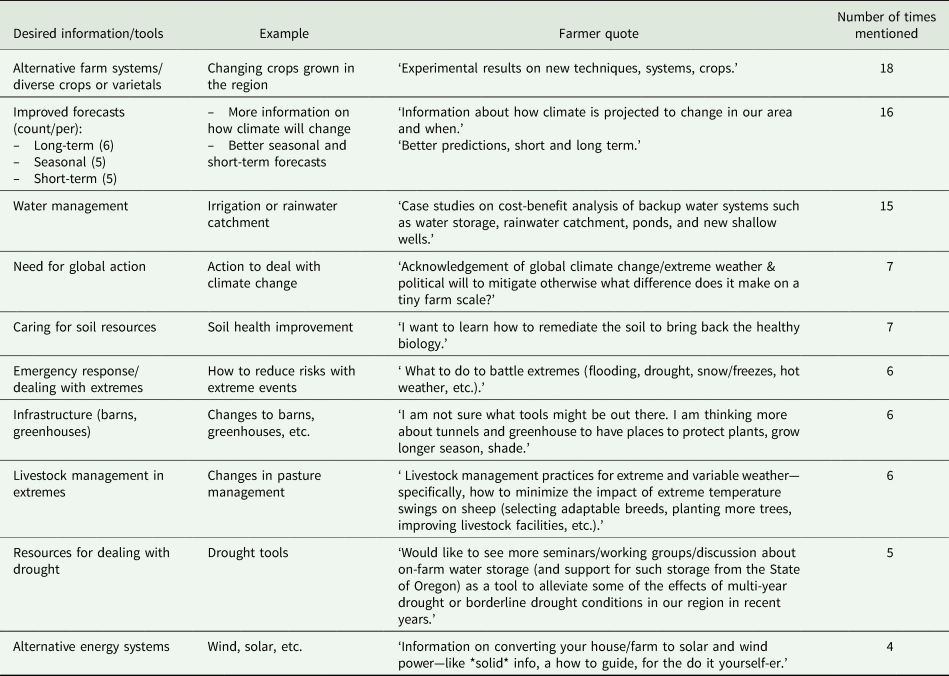

The final open-ended survey question inquired as to what tools and resources farmers would like to have to improve decision-making in the context of more extreme and variable weather (Table 3). The majority of respondents did not articulate the need for specific tools, but focused on the informational content they want. The most common request was improved information about alternative farming systems, including new crop varieties and general ways to modify the crop/livestock system to cope with a changing climate. The second most common request was a desire for improved forecasts; however, there was significant diversity in what kinds of weather and climate information that farmers wanted, from short-term to longer-term forecasts.

Table 3. Respondents were asked the open-ended question, ‘What tools or resources would you like to see that might help you make better decisions in the context of more extreme and variable weather?’ (n = 50)

Multiple responses accepted.

Small farmer respondents articulated a need for general tools and resources to make better decisions when faced with extreme and variable weather, including the need for improved forecasts, identification of new farming techniques (e.g., alternative crops, season extension) and improvements to water management systems, as well as strategies and tools for dealing with more extreme and variable weather. Indeed, decision-making tools and resources are increasingly called for as an important part of landowner outreach and education in the context of climate-informed decision-making. Yet it has been argued that creating usable climate science information will require an iterative process that builds strong linkages between scientists and decision makers, facilitated through different forms of engagement (Dilling and Lemos, Reference Dilling and Lemos2011).

This short survey and needs assessment is a first step for the Southern Willamette Valley small farm community, OSU Extension and regional partners to assess concerns and needs related to projected climate changes. This work highlights the importance of gaining local, place-based information on farmer perspectives on climate change, their attitudes toward climate action and their need for climate-informed resources (Chatrachyan et al., Reference Chatrchyan, Erlebacher, Chaopricha, Chan, Tobin and Allred2017; Lane et al., Reference Lane, Chatrchyan, Tobin, Thorn, Allred and Radhakrishna2018; White et al., Reference White, Faulkner, Sims, Tucker and Weatherhogg2018). This work is therefore a critical first step in providing a grounded perspective for county-based Extension, as a community of practice (Roesch-McNally et al., Reference Roesch-McNally, Benning, Wilke, Arbuckle, Morton, Lachapelle and Albrecht2019), as they seek to provide services to small farmers who are dealing with challenges associated with climate change.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170519000267.