1. Introduction

Schools in most parts of the globe serve populations of students who are culturally or linguistically diverse. At the same time, research suggests that current and prospective teachers often do not feel confident about teaching to a multicultural classroom (Krulatz, Steen-Olsen & Torgersen, Reference Krulatz, Steen-Olsen and Torgersen2018). Some pre-service teachers also seem to lack knowledge and understanding of their own cultural background and may not see cultural differences between themselves and their students (Çiftçi & Savaş, Reference Çiftçi and Savaş2018). At the policy level, preparing teachers to work across cultures is also recognised as an important issue. A number of recent European policy briefs have flagged that the teaching population remains largely homogenous and feels not well enough prepared to teach in increasingly diverse classrooms or about the growing diversity in society (e.g. Siarova & Tudjman, Reference Siarova and Tudjman2018).

One potential way to raise awareness and understanding of cultural diversity among pre-service teachers is virtual exchange (VE), a method of engaging students in online intercultural collaboration projects with partner classes within their programmes of study (Rets, Rienties & Lewis, Reference Rets, Rienties and Lewis2020; Rienties & Rets, Reference Rienties and Rets2022). In a VE, pre-service teachers do not need to travel abroad to participate and interact with a different culture. They can discuss issues related to their curricula with their VE partners from a different country and collaborate with them online to create educational materials and activities.

It is widely argued that participation in VE constitutes a positive learning experience (Çiftçi & Savaş, Reference Çiftçi and Savaş2018; Lewis, Rienties & Rets, Reference Lewis, Rienties, Rets, Potolia and Derivry-Plard2023). Most studies have examined different benefits of VE for learning, including the development of competences related to intercultural learning, such as intercultural effectiveness (IE) (Avgousti, Reference Avgousti2018). However, there is a lack of research that has explored whether the effects of VE on intercultural learning when conducted with pre-service teachers are positive for all learners as reported by participants, and what experiences in VE lead participants to report higher or lower IE gains.

To this end, we first explored the impact of VE on the perceived development of IE among 55 participating pre-service teachers in two different VEs using the IE scale (Portalla & Chen, Reference Portalla and Chen2010). A particular new contribution of this study is the adoption of the sequential mixed-methods research design, whereby the calculation of IE gain was used to cluster and implement the qualitative analysis of participants’ lived experiences in VE. We analysed 486 diary entries from 27 participants and contrasted participants’ experiences with VE at varying levels of reported IE gains.

2. Literature review

2.1 Competence development and intercultural learning in VE

A number of studies demonstrate the benefits of VE for participants’ intercultural growth (Çiftçi & Savaş, Reference Çiftçi and Savaş2018; European Commission, 2017). Such benefits include awareness of heterogeneity in both their own and their VE partners’ culture, increased knowledge, awareness, and interest towards other cultural perspectives, as well as the acquisition of strategies for successful intercultural communication (Dugartsyrenova & Sardegna, Reference Dugartsyrenova and Sardegna2019; Godwin-Jones, Reference Godwin-Jones2019). The aspects of intercultural learning particularly highlighted by VE research include knowledge about one’s own and others’ culture (Avgousti, Reference Avgousti2018), and a positive change of perspective on VE partners’ culture (Çiftçi & Savaş, Reference Çiftçi and Savaş2018). As VE participants are encouraged to gather information about their VE partners’ sociocultural context, it helps them avoid stereotyping and attributing individual behaviours to cultural characteristics (Flowers, Kelsen & Cvitkovic, Reference Flowers, Kelsen and Cvitkovic2019). Intercultural development in VE is facilitated by the fact that VE participants are not merely assigned to international peers but are asked to collaborate with them on shared tasks. To be able to work together they need to understand their VE partners, and to be understood (O’Dowd, Sauro & Spector-Cohen, Reference O’Dowd, Sauro and Spector-Cohen2020).

Despite the demonstrated benefits of VE, several research studies have provided emerging findings that the process of competence development among VE participants is variable, and not all participants report a similar level of learning gains at the end of a VE (Rienties, Lewis, O’Dowd, Rets & Rogaten, Reference Rienties, Lewis, O’Dowd, Rets and Rogaten2022; Schenker, Reference Schenker2012). Schenker (Reference Schenker2012) showed no significant effects of VE on participants’ self-assessment of their intercultural learning in a semester-long American–German VE. It was hypothesised that participants’ high initial self-assessment prevented them from reporting substantial learning gains. Rienties et al. (Reference Rienties, Lewis, O’Dowd, Rets and Rogaten2022) investigated the development of technological and foreign language competences reported by over 600 participants in 23 VEs. Their study showed that VE does not generate learning by osmosis. Participants in the study’s experimental condition (VE) did not have significantly higher competence growth relative to the control condition (no VE, continuation of normal classes).

In light of the evidence that not all participants benefit from VE to a similar extent, it is important to explore the factors and experiences that may facilitate or hinder learning success in VE. However, the number of studies that address this topic remains limited, and the few previous large-scale VE projects (e.g. INTENT, EVOLVE) did not aim to explore competence development in VE among pre-service teachers.

Among the few VE studies that addressed this topic is that of Lee and Park (Reference Lee and Park2017), who found there was a relationship between the successful collaboration of VE participants and the development of their knowledge base and competences. Their study showed that participants’ self-efficacy, VE infrastructure (e.g. sound quality), and quality of VE activities (the degree to which students actively interacted with VE partners and solved problems together successfully) had a significant effect on participants’ reported intercultural development.

Sevilla-Pavón (Reference Sevilla-Pavón2019) used a post-test questionnaire and focus group interviews to investigate the difference in participants’ perceived intercultural learning in a VE conducted in participants’ mother tongue versus a VE carried out in English as a lingua franca. The author found that the mean score values for intercultural learning were considerably higher in the VE carried out in lingua franca. An explanation for this difference provided by the author from the qualitative data analysis was that students reported similarities between their home culture and the culture of their VE partners, which might have had a positive effect on their perceived cultural learning. The minimisation of cultural difference is a stage of intercultural development put forward by Bennett (Reference Bennett1986), followed by acceptance of the cultural difference, adaptation or development of empathy towards them, and integration or referring to this difference as an essential and joyful aspect of life.

Another factor that has been reported to affect intercultural learning in VE besides participants’ self-efficacy, the quality of VE activities, and engagement with cultural difference concerns the moments of communication breakdown in VE. Failures of understanding that can happen in a VE cause participants to “notice” linguistic features and behavioural patterns that occur during collaboration. VE participants start adjusting their behaviour to overcome the lack of understanding and “negotiate meaning” with their partners. This process of “noticing” and “negotiating” may enhance participants’ intercultural growth (Helm & Guth, Reference Helm, Guth, Farr and Murray2016; Vinagre, Reference Vinagre, Martín-Monje, Elorza and García Riaza2016a, Reference Vinagre, Wang and Winstead2016b).

2.2 Intercultural effectiveness (IE)

Terms used to describe intercultural learning include intercultural communication competence (ICC) and IE (Bradford, Allen & Beisser, Reference Bradford, Allen and Beisser2000). Deardorff and Arasaratnam-Smith (Reference Deardorff and Arasaratnam-Smith2017) found that these two terms are often used interchangeably in the research literature. In this study, following Özdemir (Reference Özdemir2017), IE represents a dimension of ICC and is defined as “the use of verbal and nonverbal communicative behaviours, which helps individuals to interact interculturally by means of suitable and effective actions” (p. 513).

A widely validated scale (e.g. Baroni et al., Reference Baroni, Dooly, García, Guth, Hauck, Helm and Rogaten2019; Özdemir, Reference Özdemir2017) for assessing IE is the instrument developed by Portalla and Chen (Reference Portalla and Chen2010). Our study focused specifically on IE for two reasons. First, IE is particularly suited to a context where what is at stake is not the capacity of individuals to adjust to living in a host culture, but the ability of remote collaborators to communicate successfully across cultural boundaries (Özdemir, Reference Özdemir2017). Second, IE refers to the behavioural facets of ICC (Portalla & Chen, Reference Portalla and Chen2010), which is in line with the aims of this study – to analyse participants’ reported behaviours and identify the critical experiences in their intercultural learning as part of VE.

With these aims and motivations in mind, we consider the following research questions in this study:

-

1. What proportion of pre-service teachers overall report growth in IE over time in a VE?

-

2. How does the (perceived) development of IE among pre-service teachers relate to their views on VE and their experiences of intercultural communication?

3. Methods

3.1 Setting and participants

In this mixed-methods study, we analysed the data from two VEs involving 55 pre-service teachers. These VEs were carried out in 2017/2018 as part of the Evaluating and Upscaling Telecollaborative Teacher Education (EVALUATE) project, which was managed by an international group of researchers and public authorities (Baroni et al., Reference Baroni, Dooly, García, Guth, Hauck, Helm and Rogaten2019). The use of the two VEs in this study was a means of assessing whether the patterns in the findings were consistent and could be considered to have a level of generalisability (Robinson, Reference Robinson2014). Ethics approval for this study was provided by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Open University, UK, HREC-2655/Rogaten.

VE1 was carried out over three months, in Portuguese as the working language. VE1 participants were seven Portuguese and five Brazilian graduate-level pre-service teachers studying special needs education, most of whom were in part-time employment. The main tasks VE1 participants had to complete were as follows: (1) preparing individual introduction videos of one another for their VE partners, which they posted on Moodle; (2) exploring the selected educational topic in the context of the two countries; and (3) collaboratively preparing a presentation.

VE2 was carried out over six weeks, in English as the working language. It was a larger implementation relative to VE1 in terms of the number of participants. Thirty-six second-year undergraduate Spanish and seven Swedish students studying to become primary school teachers took part in VE2. The three tasks for VE2 were sequenced in a similar way to those of VE1: (1) exchanging information and resources within their classroom-based programme; (2) comparing and analysing cultural practices; and (3) preparing a joint lesson plan.

3.2 Instruments

We used the 20-item IE instrument by Portalla and Chen (Reference Portalla and Chen2010), which we implemented at the beginning and end of each VE (i.e. pre-post design). In addition to the questionnaire before and after the VE, participants also completed an online learner diary at four stages during the VE, with prompts focusing on their online collaboration experience and its relationship to their IE development (for the diary prompts, please see the supplementary material).

3.3 Procedure and data analysis

RQ1 was concerned with identifying how many participants in two VEs overall report growth in IE over time. For the purposes of this study, we used the composite construct of the employed IE instrument (Portalla & Chen, Reference Portalla and Chen2010). The Cronbach’s alphas for the overall construct at pre- and post-test were α = .88 and α = .89 respectively. To address RQ1, we first calculated the total IE gain in SPSS Version 24 using the scores from the pre- and post-test IE questionnaire for the 55 participants across VE1 and VE2. Our paired samples t-test showed there was a significant difference in the scores for pre-test IE (M = 3.6, SD = .58) and post-test IE (M = 3.74, SD = .54), t(54) = −2.49, p = .02, d = .3, for the two VEs (for a more detailed analysis of the pre- and post-test scores, please see the report from the EVALUATE project; Baroni et al., Reference Baroni, Dooly, García, Guth, Hauck, Helm and Rogaten2019).

In line with Rets et al. (Reference Rets, Rienties and Lewis2020), to ensure that a representative sample was selected for further qualitative analysis, k-means cluster analysis was applied. As we were interested in the effect of perceived IE gain on participants’ views on VE and their experiences with intercultural communication, we applied the cluster analysis to the larger sample to divide all 55 participants into clusters based on their IE gain. We tried a range of cluster solutions (i.e. 2-3-4-5 clusters), and a three-cluster solution, validated by a one-way ANOVA, provided the best fit with meaningful clusters, F(2, 52) = 13.45, p = .00, n 2 = 0.34.

The resulting clusters are indicated in Table 1. All participants in cluster 3 made negative perceived IE gains.

Table 1. Average intercultural effectiveness (IE) gain by cluster

RQ2 was concerned with the experiences reported by pre-service teachers that influenced their perceived IE gain. To address RQ2, a sample quota based on cluster and number of VE participants was used to select the learner diaries completed at all four different stages of the VE for qualitative analysis. We selected participants for whom there were no missing data in any of the diary entries, and whose diary entries were more extensive (Dooly & Vinagre, Reference Dooly and Vinagre2022).

We ensured an equal number of participants in each of the three respective clusters (Rets et al., Reference Rets, Rienties and Lewis2020). As the pre-service teachers who reported high and medium IE gains outnumbered the pre-service teachers who reported low gains, all identified participants with low IE gains (n = 9) were included in the analysis. Thus, the learner diaries of 27 participants were selected, and each resulting cluster contained nine participants (33%).

The qualitative diary entries of the selected participants in the three clusters were analysed inductively in NVivo 11, using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006), with 486 entries analysed in total (22,205 words). The analysis aimed to identify potential relationships between participants’ reported IE gains, their views on the VE, and their experiences with intercultural communication during the VE. The unit of analysis in our coding system was one entry (one full response to a question in the diary, 30 words in length on average), and the entries could be given multiple codes. Altogether, our thematic analysis identified 235 codes that were divided into six larger themes (see Table 2).

Table 2. Summary and definition of the themes elicited in this study

4. Results

4.1 RQ1: What proportion of pre-service teachers overall report growth in IE over time in a VE?

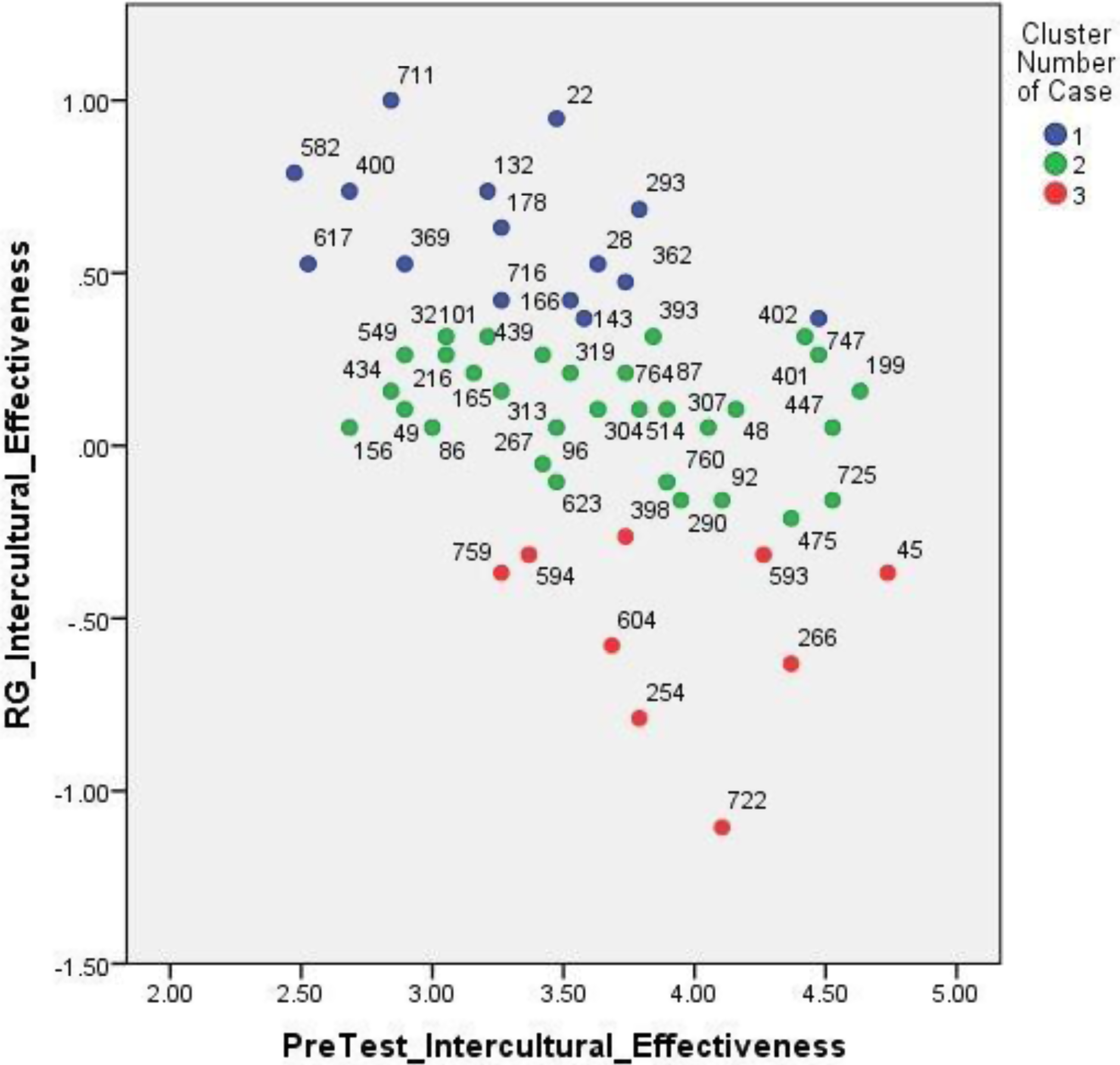

Across VE1 and VE2, most participants (70%) reported a positive perceived IE gain, while several participants (30%) made no or negative perceived IE gain over the course of the VE. Similar positive IE gains scores were reported across the wider EVALUATE project (Baroni et al., Reference Baroni, Dooly, García, Guth, Hauck, Helm and Rogaten2019), indicating the representativeness of the two selected VEs from a quantitative perspective. Figure 1 illustrates the scatterplot of pre-test IE and IE growth using the k-means cluster analysis.

Figure 1. Scatterplot with three clusters for VE1 and VE2

In Figure 1, cluster 1 with high perceived IE gains is coloured in blue, cluster 2 with medium perceived gains, in green, and cluster 3 with low perceived gains, in red. The low IE gain cluster had the fewest number of participants, which further supports the finding on the number of participants who have reported positive gains. Although on average most VE participants reported IE growth, as indicated in Figure 1 not all participants benefited equally from the VE. There was a substantial variation in terms of growth in IE between the clusters, which indicates a non-universal and non-linear development in participants’ IE skills. This result highlights the importance of exploring the lived experiences of the VE participants, as will be done in the following section.

4.2 RQ2: How does the (perceived) development of IE among pre-service teachers relate to their views on VE and their experiences of intercultural communication?

The heatmap in Figure 2 illustrates the frequency of contributions of different clusters to each theme. The intensity of colour in the heatmap represents the saliency of the theme with a specific cluster (Murphy, Reference Murphy2020). As can be seen from the heatmap, all themes, with the exception of Breakthroughs, had contributions from all clusters. At the same time, some themes (Expectation of VE – cultural learning and Positive about VE) had largely similar frequency and kinds of contributions among the three clusters, whereas other themes (Negative about VE, Challenges, Positive about VE partners) were more salient with a certain cluster. Thus, we next present our results by theme and highlight how the different clusters contributed to each of them.

Figure 2. Heatmap illustrating the frequency of contribution of the three clusters (N = 27) to each theme

4.2.1 Expectation of VE – cultural learning

Two questions in diary 1 (D1Q1 and D1Q3) prompted participants to reflect (a) on their past experience of working cross-culturally using online technologies and (b) on their expectations of VE. Our analysis showed that many participants (64%) across the clusters stated they had had no prior experience of using online tools to communicate with people in other countries. None of the remaining participants who reported they had such experience stated that they used intercultural communication for their studies or in professional contexts. This might explain why the expectation of most participants elicited in diary 1 was to learn about a new culture in the course of the VE.

P_178: I have never shared messages with people from other cultures. Perhaps as a one off on Facebook, but nothing strictly formal like this learning experience. (D1Q1, male, Spain, VE2, cluster 1)

P_254: I hope to learn about new cultures, their customs, and what other people the same age as me or not of a similar age like doing. (D1Q3, female, Spain, VE2, cluster 3)

Interestingly, since all participants were pre-service teachers, one would expect that in response to D1Q3 (“What do you hope to achieve or learn from this VE?”) they would also mention exploring different perspectives on education or aspects of their future professional routine as part of their learning. We found that only 28% of participants stated such expectations, and they all came from VE1, where most participants were in part-time employment. The other participants started reflecting on their VE partners’ educational systems only in the later stages of the project.

4.2.2 Positive about VE

Questions in each of diaries 2–4 prompted participants to reflect on the kind of experiences they were having with VE, and the extent to which these experiences led to learning about their partners’ culture. Our analysis showed that cluster 1 participants with high perceived IE gain contributed the most to the theme Positive about VE among the three clusters and expressed more readiness than other clusters to continue being involved in intercultural communication in the future. They stressed that VE made them more autonomous as intercultural communicators and stimulated their curiosity to explore further the culture of their VE partners beyond the VE.

P_132: It’s the first time that I do something with foreign partners and this contributed in a significant way to my personal and professional journey. Today I feel more comfortable in sharing my knowledge and also my own doubts with my Portuguese colleagues. In addition, I start wondering about going to Portugal and having the opportunity to learn more with colleagues/professors from there. (D4Q7, female, Brazil, VE1, cluster 1)

Additionally, participants in cluster 1 talked more often than other clusters about the possibility of taking part in a similar VE and/or organising VE for their students in the future, as they felt VE contributed to their professional growth and might be beneficial to their own students.

P_178: Yes, as a future teacher I would like my students to have an experience like this with partners the same age as them from a country that doesn’t speak Spanish [their mother tongue]. (D4Q5, male, Spain, VE2, cluster 1)

At the same time, our analysis further showed that although the other two clusters – clusters 2 and 3 with medium and low perceived IE gains – talked more neutrally about VE than cluster 1, they were not entirely negative about it. There was an overall perception among participants that intercultural communication can be a valuable experience, specifically because it generates new knowledge, and that VE can facilitate this experience. Participants like 759 and 96 highlighted the collaborative nature of VE and how it facilitates acquiring “first-hand” knowledge about other cultures without leaving one’s country of residence.

P_759: I learnt that if you don’t do activities like this, there are things that you just don’t understand. And that by doing projects like this, you gain a lot of insight into other cultures, but more importantly into your own culture too. (D2Q3, female, Spain, VE2, cluster 3)

P_96: The whole experience was positive even if we take into consideration the difficulties felt as negative. I took this telecollaboration as an opportunity to improve my knowledge from a humane and professional perspective. (D4Q9, female, Spain, VE2, cluster 2)

Among the new and interesting things that participants across the clusters talked about in terms of their cultural learning were everyday aspects of the culture of their VE partners (e.g. traditions, holidays, daily routine).

P_266: I honestly think that their culture is very different from our culture. They “study” a lot more than we do, the pace of life there is different, and their meals are also at different times. In other words, their day-to-day life is different. This is one of the things that I learned, or rather, noticed myself. (D3Q3, male, Spain, VE2, cluster 3)

Furthermore, all three clusters commented that they not only got to know the “other” culture during the VE but also further explored their home culture as well, with this idea being most salient with cluster 2.

P_49: Even though I’m from Leon, I learned more about the history and culture of my city, thanks to the presentation that we gave and our partners’ presentations. (D2Q1, female, Spain, VE2, cluster 2)

P_156: I live in La Rioja [home region in Spain] and this project has allowed me to learn a lot more about Leon [university town in Spain]. (D2Q1, female, Spain, VE2, cluster 2)

P_254: I learned to appreciate aspects of my culture that I didn’t appreciate before. (D2Q3, female, Spain, VE2, cluster 3).

As mentioned earlier, in the later stages of the project some participants from each of the clusters started reflecting on their VE partners’ educational systems when talking about their cultural learning (specifically in response to D3Q3: “Have you learned anything about your own or your partners’ culture that you didn’t expect?”). For example, participants compared and contrasted teachers’ use of technology in class, class organisational techniques, average teaching workload, and teachers’ social status in the two countries.

P_604: One of the differences that I noticed is that the Swedish students don’t place as much importance on new technology, because they were born into a society that is closely linked to technology, and so they use it every day in school. On the other hand, the students from Leon (and I’d go so far as to say Spanish students in general) place more emphasis on the importance of technology, because the Spanish teaching culture is more traditionalist, and, so, they aim to develop this further. We found a number of similarities, like the fact that both sides think that teaching values to students is key to a good education and even helps tackle bullying, among other things. (D3Q3, male, Spain, VE2, cluster 3)

4.2.3 Negative about VE

The theme Negative about VE was salient with cluster 3 participants. Nine participants in cluster 3 with low perceived IE gain tended to feel less comfortable interacting with their VE partners or participating in the VE. As mentioned previously, their comments were not entirely negative about the VE, and they commented on some aspects of cultural learning, such as learning “new things” about the culture of their VE partners within the theme Positive about VE. They also displayed an awareness that participating in intercultural communication can be a positive experience. However, in the theme Negative about VE cluster 3 participants emphasised that they could not learn as much from the VE as they had expected to. They specifically referred to failing to develop skills of effective intercultural communication. They also mentioned that the VE was too short to learn extensively, or they thought a similar VE would not be useful in their future teaching practice. To exemplify, a comparative text search query in NVivo 11 for the word “learn” between clusters 1 and 3 revealed that cluster 1 often used “learn” with such elements as “lot”, “improved”, “how to”. In contrast, negation was often featured in the diaries of cluster 3 participants when they talked about their learning. This point is illustrated in Figures 3 and 4 in the supplementary material.

4.2.4 Challenges and breakthroughs

Diaries 2–4 also prompted into the reasons behind the kind of experiences with VE participants were reporting. Naturally, the “real-life” experience of online communication and collaboration meant that participants had to face some challenges. However, our analysis showed that the three clusters provided a different narrative of the faced challenges.

Most challenges reported by cluster 1 concerned language and communication problems: the participants either felt anxiety at expressing themselves in an intercultural setting, or they had difficulty understanding their VE partners, and/or difficulty in understanding the assignment. The nine participants in cluster 1 talked about these challenges in a positive light, such as not getting discouraged by the things they do not know in a VE and “continuing sharing experiences and learning from each other’s cultures” (P_22). In our analysis we labelled this narrative as Breakthroughs, as in their diaries, cluster 1 participants often reflected on how they managed to get over and/or overcome the anxieties or lack of skills they felt they initially had and pointed to specific strategies that helped them. Among the frequent words used within this theme were “at first”, “difficult”, “however”, “different”, “in the end”, “solve”, “learn”. Examples of the coping strategies featured in cluster 1 diaries included that of creating a shared Google table with the aims they wanted to achieve in a VE (P_178), asking their home partners to record them to help reduce an anxiety of “sitting in front of a camera and speaking in a foreign language” (P_22), and exchanging WhatsApp numbers to send files that were too heavy to upload online and enable continuity of communication (P_132). Participants in cluster 1 emphasized that the key to solving the difficulties they faced was collaboration, as it was mostly through the help of their partners and through negotiation that they were able to solve those difficulties.

P_178: One of the problems that we faced was having to explain things in a simple and clear way because we tended to presume that they would understand. By going into detail and thinking of a different way to explain it, we were able to convey everything that came up during the exchange. (D4Q8, male, Spain, VE2, cluster 1)

P_369: It has had a rather odd effect and, thanks to this project, I now dare to express myself naturally and without being nervous. (D4Q7, male, Spain, VE2, cluster 1)

Most of the difficulties reported by cluster 2 also concerned challenges with communication that occurred due to the language barrier. Two out of nine participants in cluster 2 commented on the challenge of working in very different time zones from their VE partners. Cluster 2 participants also talked about difficulties with the group dynamics when they did not coordinate their actions to accomplish the task or did not negotiate the differences within the team.

P_156: In my opinion, it is difficult to design tasks with so many group members, because there are varying opinions, and it is more difficult to come to an agreement. (D4Q6, female, Spain, VE2, cluster 2)

Despite commonalities with some of the challenges faced by cluster 1 participants, cluster 2 talked more about the challenges they faced during the VE and which they did not necessarily overcome, in contrast to cluster 1. They referred to these unresolved challenges as learning experiences that they might avoid in the future.

P_49: I found it easy to exchange information but keeping the relationship going was more difficult. One way of improving interaction would be to connect to the project every day, something that many of my partners did not do. (D3Q1, female, Spain, VE2, cluster 2)

Although cluster 1 held a positive view of the challenges faced and cluster 2 remained neutral but framed them as learning experiences, cluster 3 talked more often about the challenges they encountered in the VE in general, as compared to the other clusters, and more specifically about the frustration they could not overcome during the VE. The frequent reference to unresolved challenges was particularly prevalent among participants with the lowest perceived IE gain.

P_45: It [the VE] rather felt like it was something we had to do and not something we should do together as a team. It felt enforced. The second aspect was the waiting. It felt like we did not have the same deadlines which caused irritation and much waiting. (D4Q2, female, Sweden, VE2, cluster 3)

4.2.5 Positive about VE partners

We found that the relationship with VE partners was an important factor in shaping the experiences participants had with facing challenges in the VE, and the reflection on this relationship was prompted by several questions in the diaries (e.g. D2Q3: “What are your initial impressions of your virtual partners?”; D3Q1: “How do you feel about the interactions with your virtual partners so far?”).

Our analysis showed that participants in clusters 1 and 2 talked mostly positively about their VE partners. The aspects that participants seemed to have appreciated the most was that their VE partners were motivated to take part in VE and took it seriously – they were “hardworking and conscious in what they were doing” (P_307, cluster 2). They frequently commented on their VE partners being committed to preparing thoroughly for their online sessions and being open to sharing information about their culture. In contrast, participants in cluster 3 talked mainly about the lack of engagement from their VE partners.

P_722: I sometimes got the feeling that the group we collaborated with weren’t as ambitious as my group and that caused some frustration at some points. (D4Q9, female, Sweden, VE2, cluster 3)

P_254: The main challenge we faced was not being able to work on the topic we had chosen because it wasn’t a good topic for them since not everyone celebrates Christmas. (D4Q1, female, Spain, VE2, cluster 3)

Furthermore, when reflecting on VE partners, we found that the three clusters talked differently about engagement with cultural difference. Clusters 1 and 2 talked frequently either about no difference between them and their VE peers or they minimised this difference in their comments, showing awareness of the cultural difference but not scrutinising them.

P_400: There is always some sort of prior cultural stereotype, which may have some truth in it or not. We didn’t notice any this time, so it is not something we discussed. (D2Q1, female, Spain, VE2, cluster 1)

P_307: “Small world” could be the summary because no matter how far you are or how different you think we are to each other, at the end, despite the differences, we all are people and we behave similar, we have the same needs and objectives. (D4Q8, female, Spain, VE2, cluster 2)

On the contrary, participants in cluster 3 tended to contrast the two cultural contexts and talk more often about the cultural difference. Many of their comments feature a positive appraisal of these differences.

P_266: I learned that we are different. They have a culture that is different to ours, it is neither better nor worse. (D2Q3, female, Portugal, VE1, cluster 3)

P_398: My own perspective about the world is that we have different ways of living and thinking, and that our country has good ideas as much as the others have as well. (D4Q8, female, Brazil, VE1, cluster 3)

P_722: It was interesting and challenging to collaborate with people from a different country, as they seem to have different ways of thinking and working than us – so, we had to adjust ourselves to them in some ways. (D4Q1, female, Sweden, VE2, cluster 3)

5. Discussion

Although a growing body of literature reports a positive impact of VE on IE (Avgousti, Reference Avgousti2018; Dugartsyrenova & Sardegna, Reference Dugartsyrenova and Sardegna2019; Godwin-Jones, Reference Godwin-Jones2019), most of these studies have relied on qualitative approaches alone. Emerging evidence from recent studies suggests that not all students benefit equally from VE (Rets et al., Reference Rets, Rienties and Lewis2020; Rienties et al., Reference Rienties, Lewis, O’Dowd, Rets and Rogaten2022). However, the number of studies that investigate the reasons for this, particularly in relation to intercultural learning, is very limited.

In this study, we aimed to fill this gap by adopting a robust mixed-methods design. RQ1 was concerned with identifying how many participants overall reported growth in IE over the course of the VE. To answer RQ1, we first calculated the IE gain based on the widely validated instrument of Portalla and Chen (Reference Portalla and Chen2010), followed by the k-means cluster analysis. This allowed us to explore which groups of learners reported growth in IE over time across two VEs (VE1 Portugal – Brazil, VE2 Spain – Sweden), and which learners did not. We found that most students (70%) saw their participation in the VE as a positive intercultural learning experience. This result supports several VE studies (Çiftçi & Savaş, Reference Çiftçi and Savaş2018; European Commission, 2017; Vinagre, Reference Vinagre, Martín-Monje, Elorza and García Riaza2016a, Reference Vinagre, Wang and Winstead2016b) that found that VE can encourage IE. Nonetheless, as highlighted by Figures 1 and 3, as well as by our cluster analysis, some participants in cluster 2 and particularly participants in cluster 3 had negative VE experiences. Although there is a substantial gap in quantifying VE learning gains (Golonka, Bowles, Frank, Richardson & Freynik, Reference Golonka, Bowles, Frank, Richardson and Freynik2014), the emerging research evidence has signalled the variability of competence development among VE participants (Rienties et al., Reference Rienties, Lewis, O’Dowd, Rets and Rogaten2022; Schenker, Reference Schenker2012). Our study corroborated this evidence in relation to intercultural learning. It showed that some students believe they have benefited from VE more than others, and the kind of collaboration that takes place in VE does not induce all students to report high IE gains.

The results of the quantitative analysis performed in responding to RQ1 encouraged us to explore how perceived IE gain related to pre-service teachers’ views on VE and their experiences of intercultural communication, as part of RQ2. To answer RQ2, we explored the reflections of 27 VE participants using 486 diary entries and identified commonalities and differences between participants with perceived high, medium, and low IE gains.

We found a number of commonalities across the clusters. First, most participants across the sample had little or no prior experience in using online tools to communicate with people from other countries. Perhaps this may be surprising, given our current connected and global world, but as highlighted by several researchers, most students are primarily connected to local cultural groups rather than to large cross-cultural networks (Rienties & Rets, Reference Rienties and Rets2022). As our participants often talked about the opportunities VE gave them to interact with people from a different culture, our study showed that VE might be a useful way to let pre-service teachers experience being part of such larger cross-cultural networks. Second, our study showed that when talking about cultural learning, participants mainly highlighted learning about the everyday culture of VE partners. This finding is consistent with the VE research that emphasised that the aspects of cultural learning encouraged by VE include learning about other people’s cultures (Avgousti, Reference Avgousti2018). Our study further showed that in the later stages of the VE, some participants started reflecting not only on the everyday culture of their VE partners but also on the specifics of their educational context. Such reflection also represents a positive trend in the development of IE skills in this study. As has been mentioned before, VE literature suggests that VE participants need to be encouraged to gather information about their VE partners’ educational context to avoid cultural stereotyping (Flowers et al., Reference Flowers, Kelsen and Cvitkovic2019).

However, despite these commonalities, our study identified salient differences between the three clusters, which influenced their perceived IE development. Participants’ reported ability to overcome challenges in VE was the biggest factor that differentiated the clusters with high and low IE gains. All participants experienced challenges (technical, organisational, cultural) and/or anxieties (e.g. language skills, ability to express oneself) when working together in VE. However, only cluster 1 participants with high perceived IE gains talked about the so-called “breakthroughs” in overcoming these challenges, which resulted in their reported willingness to take an active part in intercultural communication after the VE. The “breakthroughs” identified in this study represent the “rich points” described in VE literature, when potential learning occurs in moments of communication breakdown and negotiation of meaning (Helm & Guth, Reference Helm, Guth, Farr and Murray2016; Vinagre, Reference Vinagre, Martín-Monje, Elorza and García Riaza2016a). In contrast to cluster 1, cluster 3 participants with low perceived IE gains were much more likely to highlight the negative aspects of the VE they had taken part in. In their comments, they referred to not having learned as much as they had hoped to from the project and the challenges they faced during the VE that they could not overcome. Cluster 2 participants with medium perceived IE gains also talked about the challenges they faced during the VE. However, they tended to see those in a more positive light and provided recommendations for how such challenges could be avoided in the future.

This finding on overcoming challenges as a critical factor in participants’ perception of IE learning complements earlier studies, which showed that participants’ self-efficacy has an important influence on their learning in VE (Lee & Park, Reference Lee and Park2017). The literature on intercultural communication refers to this as developing effective coping mechanisms, whereby learners need to develop psycho-social adjustment skills to overcome some of the stress encountered in collaborating with others from a different culture (Searle & Ward, Reference Searle and Ward1990).

The second elicited factor that differentiated the clusters was participants’ reported level of engagement with their VE partners. Among the three clusters, cluster 3 participants talked most frequently about their VE partners not being motivated, committed to the project, or not treating it seriously. In a way, this finding echoes an earlier study by Lee and Park (Reference Lee and Park2017), which showed that the degree to which VE participants actively interact with their partners and solve problems together successfully may have an impact on their perceived learning gains in VE. This finding is also largely in line with the literature on collaboration, whereby it is essential for the members of collaborating teams to possess a certain level of personal commitment to the project to have enough opportunities to create common frames of reference and a shared conception of a problem (Rets et al., Reference Rets, Rienties and Lewis2020).

The third factor evident from the qualitative analysis that influenced participants’ perceived IE development was their engagement with cultural difference. Cluster 1 participants minimised the cultural difference between themselves and their VE partners, focusing on the similarities. This finding largely supports the earlier study of Sevilla-Pavón (Reference Sevilla-Pavón2019), who found that the average perceived intercultural learning gain was higher in a VE, where students tended to reflect on the similarities between the two cultures. Our study further showed that in contrast to cluster 1, cluster 3 participants talked more about the distinct and different culture of their partners, or their partners being different from how they had imagined them before the VE, while also often referring to this as an interesting and challenging aspect of the VE. Using the terms of Bennett’s (1986) model of intercultural sensitivity, elaborating categories for otherness in cultural contexts is, in fact, a more mature stage of intercultural development than the minimization of these differences. At the “minimization” stage, one views culture through a universalist lens, where cultural differences are ignored in favour of the assumedly more important similarities between self and other. The stage that follows – the “acceptance” stage – is characterised by the greater awareness of and curiosity towards cultural differences (Bennett, Reference Bennett and Kim2017). The unresolved challenges described in this study might have encouraged cluster 3 participants to scrutinise and reflect more on their VE experiences and cultural differences than participants in other clusters. While the clusters in this study were based on participants’ self-assessment of their IE development, cluster 3 participants, thus, might have gained more from VE than they perceived.

5.1 Limitations and practical implications

An innovative research design used in this study – quantitative cluster analysis and comparative qualitative analysis of learner diaries – which has not been applied to VE data before to explore IE learning gains, allowed us to address several gaps in VE research. Had this study relied on quantitative insights alone, one might have concluded that cluster 3 participants were less successful than those in cluster 1, in that they reported lower IE gains. However, combining these insights with the qualitative analysis of their diary entries enabled us to see that cluster 3 participants did not avoid facing diversity and difference, which led them to reflect on and accept this difference more than participants in the other two clusters. Thus, analysing the data sequentially allowed a more complex and nuanced understanding of why VE might be beneficial for some learners and what kind of learning it encourages.

One limitation of this study concerned the fact that if the study were to maintain a clear separation between the quantitative and qualitative aspects of this research, this might have provided more space for a detailed analysis of the associated IE growth per subconstruct of Portalla and Chen’s scale (2010) and for highlighting finer-grained qualitative analysis of the subthemes. Furthermore, while this study analysed the aggregate data from multiple VEs, examining the possible differences between the VEs has been out of scope for this study – a gap that future research can address.

In terms of practical implications, we encourage teachers and designers of VE to hold frequent discussions with VE participants about their anxiety levels and the kind of challenges they are facing during VE collaboration. Such discussions can help learners overcome these challenges, which, as our study showed, can lead to higher perceived levels of learning gains. It is important for teachers to underline to their students that any misunderstandings in a VE should be considered as opportunities for reflection and learning and not as a failure of the learning process.

The second implication concerns the importance of strengthening collaboration between VE teams. Since our study showed that the level of commitment and engagement of collaborating partners also influences their perceived IE growth, it is important to provide more opportunities for communication between VE teams and have explicit discussions about teamwork and group organisation.

6. Conclusion

Existing evidence indicates that pre-service teachers often lack experience of working with different cultures (Krulatz et al., Reference Krulatz, Steen-Olsen and Torgersen2018), and VE has considerable potential to develop their IE skills. On the one hand, our study showed that there is a variability in students’ perceptions of their intercultural learning. We identified three factors that led to such a varied response: students’ ability to overcome challenges during VE, the level of engagement with and from their VE partners, and engagement with cultural difference. Our analysis further showed that a low IE gain in a VE does not necessarily constitute a negative learning outcome. Participants with low IE gains tended to scrutinise their experience and displayed higher levels of awareness of the cultural difference than participants with higher perceived gains. Thus, our study provided emerging evidence that VE can constitute a positive intercultural learning experience, even in the instances where students report low learning gains. As student mobility is often constrained in scenarios, such as a global pandemic, and since VE can help students acquire intercultural skills, our study also has implications for policymakers in that they should look for more opportunities to invest in VEs and promote this pedagogy among practitioners.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344023000046

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the EVALUATE project team members who have contributed tirelessly on these exchanges. The EVALUATE project was funded by Erasmus+ Key Action 3 (EACEA No 34/2015): European policy experimentations in the fields of education, training, and youth led by high-level public authorities. The views reflected in this article are ours alone and the commission cannot be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Ethical statement and competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest in this paper. All participation in the study was voluntary, and informed consent was provided prior to commencement of the assignment. The anonymity of the participants was maintained throughout the study.

About the authors

Irina Rets is a senior research fellow at the Institute of Educational Technology, the Open University, UK. With expertise in inclusive artificial intelligence (AI) and linguistics, Irina’s current research explores how technology can be leveraged to improve social justice in the learning contexts and more generally in society.

Bart Rienties is a professor of learning analytics and the lead of the learning analytics and learning design research programme at the Institute of Educational Technology, the Open University, UK. He has published over 285 academic outputs and is the second most published author on networks in education in the period 1969–2020.

Tim Lewis is an honorary associate of the Open University, UK. From 2013 to 2017, Tim was director of postgraduate studies in the OU’s Centre for Research in Education and Educational Technology. He has extensive experience in implementing large-scale, international virtual exchange projects.

Author ORCIDs

Irina Rets, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8832-0962

Bart Rienties, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3749-9629

Tim Lewis, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4528-1227