INTRODUCTION

The Kostenki Upper Paleolithic

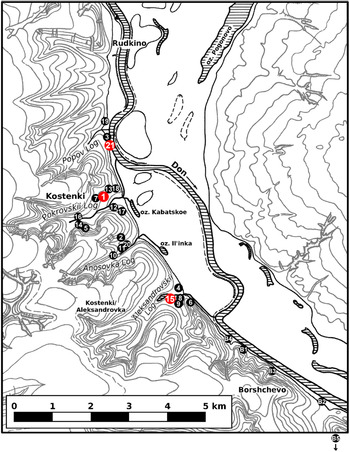

A sound reconstruction of Upper Paleolithic cultural change requires multilayered sites that show the chronostratigraphic relationships of different assemblages. For this reason, the complex of 26 open-air sites around the villages of Kostenki and Borshchevo (Voronezh region, Russia; Figure 1; henceforth simply “Kostenki”) is key for the period in Eastern Europe. For over 20 millennia hunter-gatherer groups left behind occupation debris, which frequently became buried by low-energy accumulation of sediment. As a result, around half of Kostenki’s sites are multilayered, and some have deep sequences with multiple archaeological horizons separated by sterile ones. Kostenki thus provides an unusually high-resolution archaeological record spanning a large part of the Late Pleistocene.

Figure 1 Location of the Kostenki-Borshchevo sites, with Kostenki 21, Kostenki 1 and Kostenki 15 highlighted.

Kostenki also benefits from a well-understood geological framework (Figure 2), which allows correlation of the different sites. In reality, stratigraphies are complex and often impacted by post-depositional disturbance, but this framework is nonetheless a firm basis for chronology building. The sites also contain abundant material suitable for radiocarbon dating. This includes anthropogenic accumulations of animal bone.

Figure 2 Idealized schematic column of the Kostenki region’s geological sequence, showing the major Late Pleistocene/Holocene geological units. The blue bars show the relative chronological positions within this sequence of selected layers from different Kostenki sites: namely recently/well-dated assemblages and others mentioned in this paper. Layers’ radiocarbon chronologies are based on Damblon et al. (Reference Damblon, Haesaerts and van der Plicht1996), Sinitsyn et al. (Reference Sinitsyn, Praslov, Svezhentsev, Sulerzhitskiy and Sinitsyn1997), Sinitsyn and Hoffecker (Reference Sinitsyn and Hoffecker2006), Reynolds et al. (Reference Reynolds, Lisitsyn, Sablin, Barton and Higham2015, Reference Reynolds, Dinnis, Bessudnov, Devièse and Higham2017), Douka and Higham (Reference Douka and Higham2017), Dinnis et al. (Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Reynolds, Douka, Dudin, Khlopachev, Sablin, Sinitsyn and Higham2018, Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Reynolds, Devièse, Pate, Sablin, Sinitsyn and Higham2019a, this paper) and Pryor et al. (Reference Pryor, Beresford-Jones, Dudin, Ikonnikova, Hoffecker and Gamble2020). Note each layer’s age range represents the period within which each assemblage probably falls, rather than expressing the duration of occupation(s). Note also that most of the loess-like loam deposits appear to date to the earlier part of the given time range.

Producing accurate bone dates has proved challenging, due to the well-documented problem of exogenous carbon leading to erroneously young results (Higham Reference Higham2011). More recent bone-dating work using more effective sample pretreatment methods has provided improved radiocarbon chronologies for some Kostenki sites (e.g., Douka and Higham Reference Douka and Higham2017; Dinnis et al. Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Reynolds, Douka, Dudin, Khlopachev, Sablin, Sinitsyn and Higham2018, Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Reynolds, Devièse, Pate, Sablin, Sinitsyn and Higham2019a), but the precise chronological relationships between others remain unresolved (e.g., Hoffecker et al. Reference Hoffecker, Holliday, Stepanchuk and Lisitsyn2018; Lisitsyn Reference Lisitsyn2019).

Given its regional importance, a robust, high-resolution chronology for Kostenki has significance well beyond the complex. Here we present and discuss new radiocarbon dates for three key assemblages.

Kostenki 15 (Gorodtsovskaya)

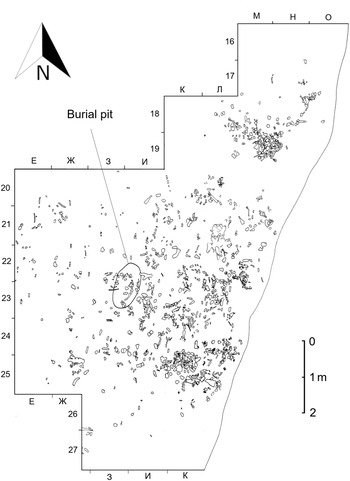

The single-layered Kostenki 15 (Figures 1 and 3) was excavated by A.N. Rogachev in 1952. The main concentration of finds was interpreted by Rogachev as the remains of a dwelling, within which was an infant burial. A smaller cluster of finds was located to the north of this (∼ squares М-Н–18-19; Figure 3). As well as the burial and lithic and osseous tool assemblages, Rogachev recovered a large number of horse bones (n=1501, MNI=11), some of which found in anatomical position (Rogachev and Sinitsyn Reference Rogachev and Sinitsyn1982; Sergin Reference Sergin2016).

Figure 3 Plan of Kostenki 15 (modified from Sinitsyn Reference Sinitsyn2004), showing the location of the burial pit.

Kostenki 15 is the eponymous site of the Gorodtsovian (Efimenko Reference Efimenko1956; Sinitsyn Reference Sinitsyn1982). Gorodtsovian lithic assemblages are characterized by an abundance of splintered pieces and short, steep-faced end-scrapers, as well as a high incidence of tool types historically viewed as characteristically “Mousterian” (e.g., side-scrapers). Technotypological variation between sites previously classified as Gorodtsovian is, however, markedly high; to an extent the taxon has been used as a catch-all for assemblages not classifiable as Aurignacian (typified by finely-edge-retouched bladelets) or Gravettian (typified by backed ones) (Sinitsyn Reference Sinitsyn2018). Despite this variation a cultural link between Kostenki 15, Kostenki 14 Layer II, and Kostenki 12 Layer I is demonstrated by the presence of idiosyncratic mammoth-bone “paddles” (Figure 4). Further assemblages from Kostenki 16 and Mira on the Lower Dnieper (Stepanchuk Reference Stepanchuk2013; Hoffecker et al. Reference Hoffecker, Holliday, Stepanchuk and Lisitsyn2018) are possibly but less certainly related.

Figure 4 Gorodtsovian bone “paddles” from Kostenki 15 (left) and Kostenki 14 Layer II (right).

The broad chronology of Kostenki’s Gorodtsovian assemblages is known from their association with the Upper Humic Bed (see Figure 2). The assemblage whose geochronological position is clearest is Kostenki 14 Layer II, which lies close to the center of the Upper Humic Bed (Velichko et al. Reference Velichko, Pisareva, Sedov, Sinitsyn and Timireva2009; Sedov et al. Reference Sedov, Khokhlova, Sinitsyn, Korkka, Rusakov, Ortega, Solleiro, Rozanova, Kuznetsova and Kazdym2010). A finer resolution chronology is hindered by an inconsistent radiocarbon record (Sinitsyn et al. Reference Sinitsyn, Praslov, Svezhentsev, Sulerzhitskiy and Sinitsyn1997; Sinitsyn and Hoffecker Reference Sinitsyn and Hoffecker2006). Kostenki 15 has been especially poorly dated until now: all three previously published radiocarbon dates of 16,895 ± 200 BP, 21,720 ± 570 BP and 25,700 ± 250 BP (see Appendix) appear to be underestimates.

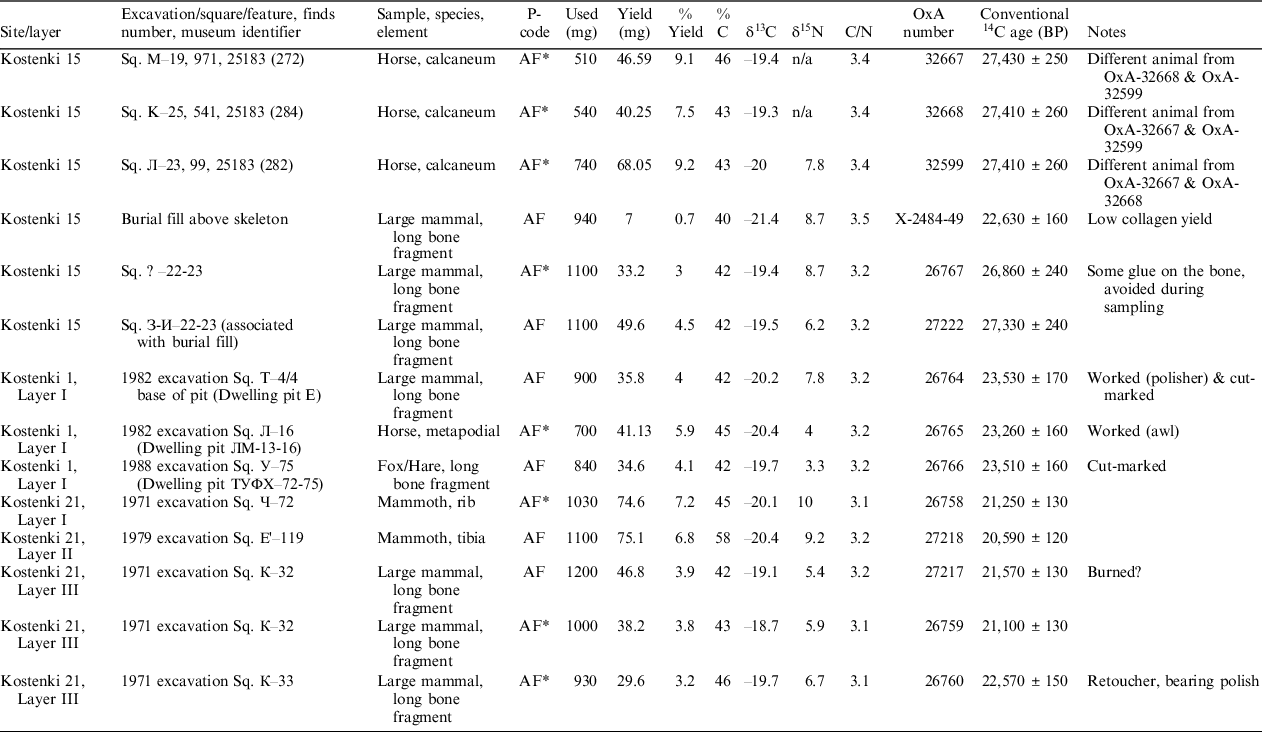

To improve Kostenki 15’s chronology we produced six new radiocarbon dates (Table 1). Two were from long bone fragments associated with the burial fill, with a third from a long bone fragment whose precise provenance is uncertain, but which came from the site’s main cluster of material. The three remaining dates were from bones identifiable with certainty as horse. To ensure we dated different animals we selected three right-side calcanea. Two of these three specimens were found in the larger concentration of finds, with the other from the smaller, northern cluster (Table 1, Figure 3). All samples were processed using the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit’s (ORAU) routine procedure, as described by Brock et al. (Reference Brock, Higham, Ditchfield and Bronk Ramsey2010). Because glue was visible on the surface of one sample (OxA-26767), we applied an additional acetone, methanol and chloroform solvent wash step (Table 1). One of our primary objectives was to test whether the horse bone accumulation was the result of activity over a brief period. No glue was evident on the three dated horse bones (OxA-32667, OxA-32668 and OxA-32599), but to allow a greater confidence in the results we also applied a solvent wash to these samples (Table 1).

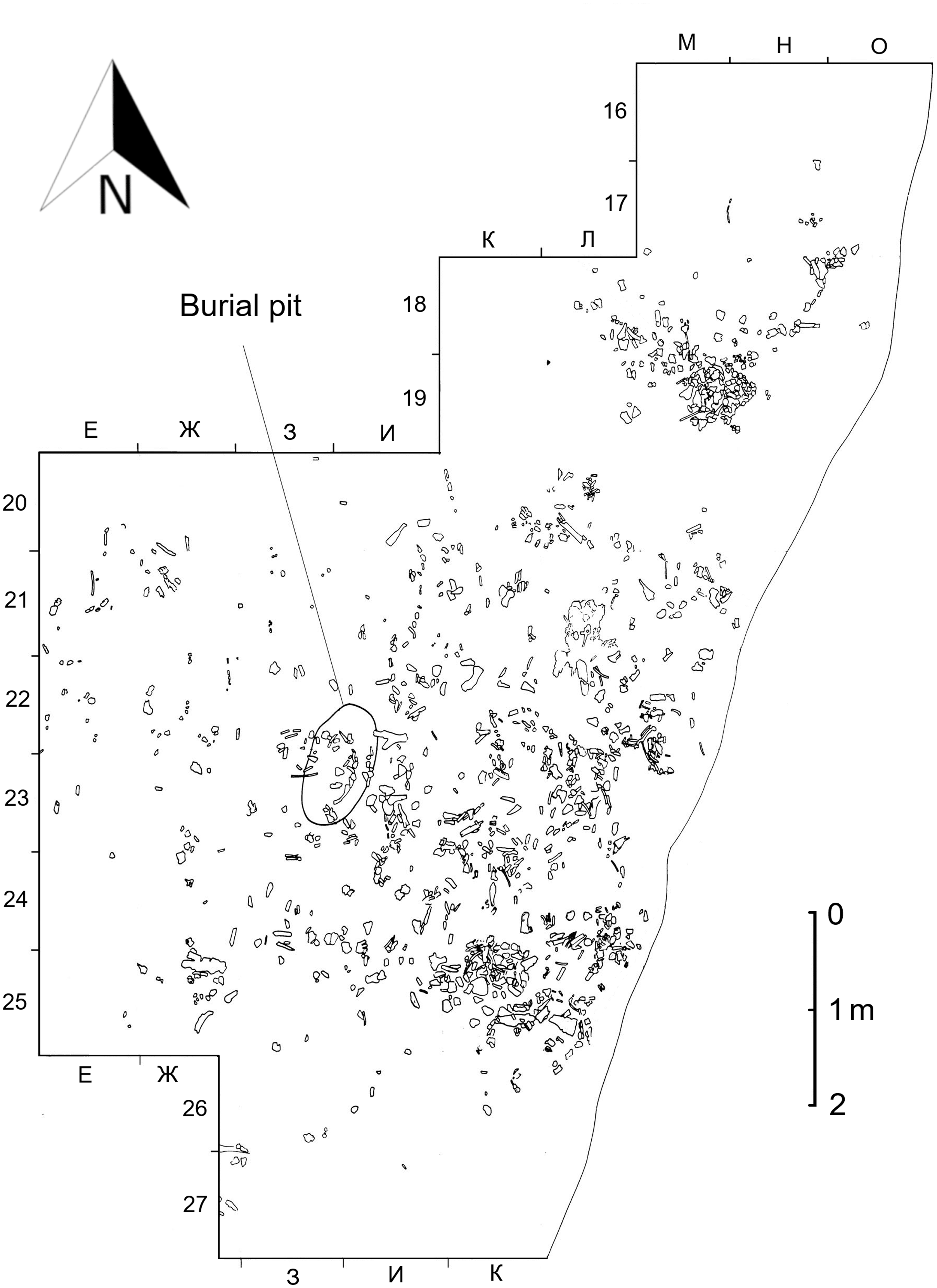

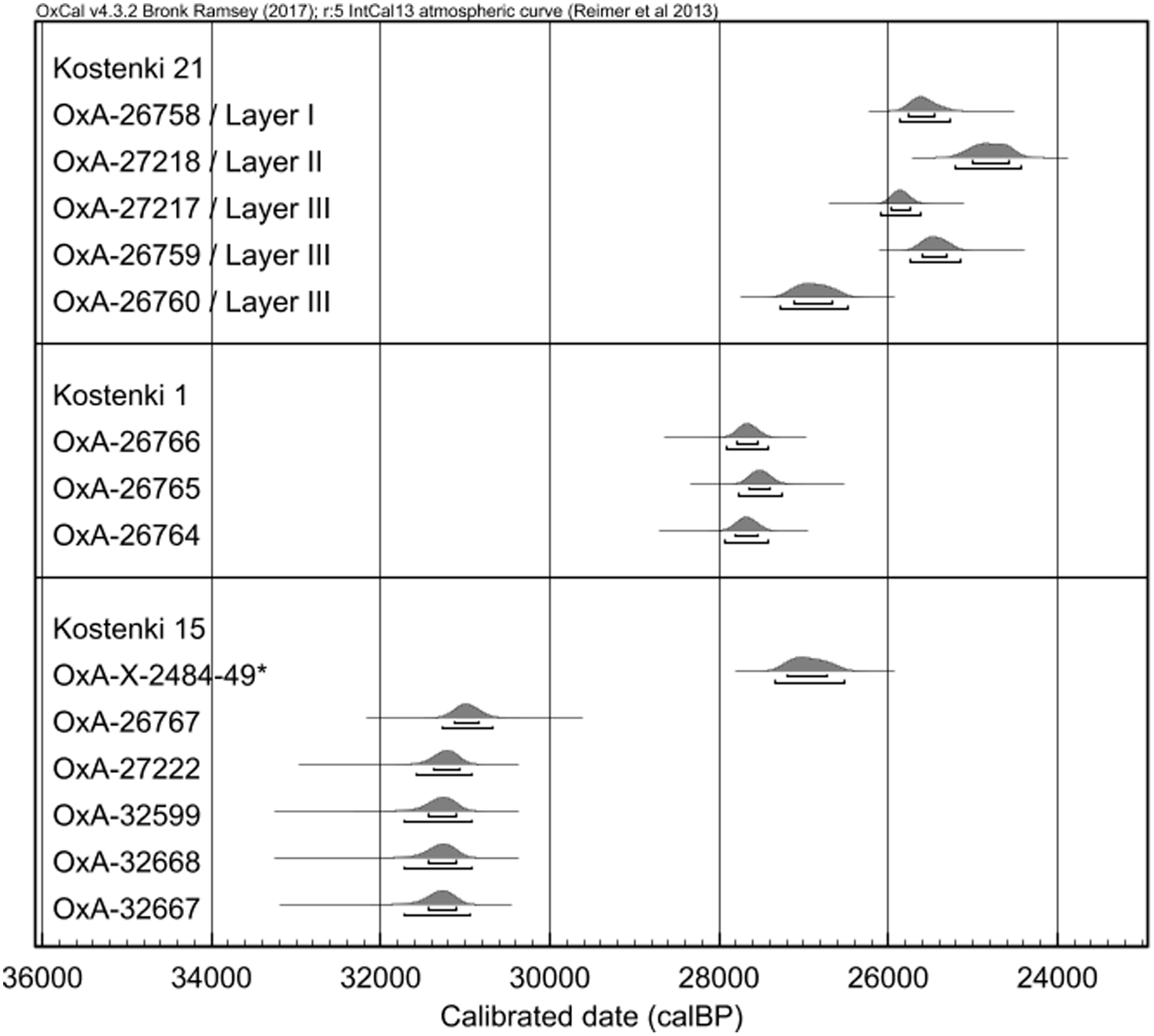

Table 1 New radiocarbon dates for Kostenki 15, Kostenki 1 Layer I and Kostenki 21 (see also Figure 5). No other dates (or failed dates) were produced for these contexts in the course of this work. P-Code refers to the pretreatment method applied: AF denotes ultrafiltration of bone collagen extract (see Brock et al. Reference Brock, Higham, Ditchfield and Bronk Ramsey2010), with * denoting an acetone, methanol and chloroform solvent wash. Stable isotope ratios of carbon and nitrogen are presented in ‰ relative to VPDB and AIR respectively with a mass spectrometric precision of ±0.2‰ and ±0.3‰ respectively. Yield represents the weight of ultrafiltered collagen extracted in milligrams. %Yld is the percent yield of extracted collagen with respect to the starting weight of the bone analyzed. Used is the weight of bone used, also in mg. %C is the carbon present in the combusted gelatin and ought to be ∼40–43%. CN atomic ratios ought to range from 2.9 to 3.5.

Excluding the sample for which the collagen yield was low (OxA-X-2484-49), our five results of ∼27.5–27 ka BP show a good degree of consistency (Table 1, Figure 5). That said, given the difficulty of producing accurate dates for glued bones even when an additional solvent wash step is applied (e.g., Dinnis et al. Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Reynolds, Devièse, Pate, Sablin, Sinitsyn and Higham2019a), the youngest of these results (OxA-26767; 26,860 ± 240 BP) is best treated as a minimum age. Despite coming from different parts of the site, the remaining four dates, including the three identified horse bones, show a particularly pronounced level of consistency at ∼27.4–27.3 ka BP (Table 1). This is consonant with them belonging to a broadly contemporary deposit.

Figure 5 Calibrated ages for the age determinations shown in Table 1 from Kostenki 21, Kostenki 1 Layer I, and Kostenki 15. The asterisk in OxA-X-2484 denotes a radiocarbon determination with a health warning due to low collagen yield (0.7%). The dates were calibrated using the IntCal13 curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013) and the OxCal 4.5 platform (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2017).

Kostenki 1 (Polyakovskaya), Layer I

The uppermost Layer I of Kostenki 1 is among Eastern Europe’s most important Upper Paleolithic sites. Extensive excavation of the layer throughout the 20th century, primarily by P.P. Efimenko, Rogachev and then N.D. Praslov, unearthed a large archaeological assemblage (>55,000 lithic pieces) and the remains of habitation complexes (Rogachev et al. Reference Rogachev, Praslov, Anikovich, Beliaeva and Dmitrieva1982; Anikovich et al. Reference Anikovich, Lisitsyn, Platonova, Popov, Dudin and Fedyunin2019; Figure 6). An abundance of material has allowed a good characterization of the assemblage. It includes shouldered points, Kostenki knives and female figurines: the defining features of the Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture (KAC). Among other assemblages attributed to the same cultural group are Kostenki 14 Layer I, Kostenki 13, Kostenki 18, Avdeevo and Zaraisk, with Khotylevo 2 and Gagarino also sometimes linked (Sinitsyn Reference Sinitsyn2007; Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Dinnis, Bessudnov, Devièse and Higham2017; Lisitsyn Reference Lisitsyn2019).

Figure 6 Plan of Kostenki 1 Layer I, showing the first habitation complex (right) and the incompletely excavated second complex (left) (modified from Desbrosse and Kozłowski Reference Desbrosse and Kozłowski2001). The different pits from which our dated samples came are marked.

Because some of these sites have large and well-defined assemblages their cultural connection is generally accepted. As a result, the longevity of occupation(s) represented at single sites—and the longevity of the KAC group overall—has been widely discussed (e.g., Amirkhanov et al. Reference Amirkhanov, Lev and Seleznëv2001; Anikovich et al. Reference Anikovich, Popov, Platonova, Anikovich, Popov and Platonova2008; Zaretskaya et al. Reference Zaretskaya, Gavrilov, Panin and Nechushkin2018). Debates largely focus on how to interpret the sites’ considerable number of radiocarbon dates. Some favor a “long chronology,” viewing a several-thousand-year span of dates as evidence that archaeological layers represent long occupations or several short ones over a long time. Others favor a “short chronology,” viewing many of the dates as inaccurate, and seeing multiple phases of activity represented in a layer as likely to be chronologically indistinguishable at the resolution of radiocarbon dating (see Zaretskaya et al. Reference Zaretskaya, Gavrilov, Panin and Nechushkin2018 for an overview of these debates).

There are 55 previous dates for Kostenki 1 Layer I, which span ∼15,000 14C yrs (Sinitsyn et al. Reference Sinitsyn, Praslov, Svezhentsev, Sulerzhitskiy and Sinitsyn1997; Anikovich et al. Reference Anikovich, Popov, Platonova, Anikovich, Popov and Platonova2008; Khlopachev Reference Khlopachev2016; Zheltova and Zaretskaya Reference Zheltova and Zaretskaya2018; Appendix 1). If the younger dates (<20 ka BP) and less precise dates (those with errors >1,000) are dismissed as probably problematic, the remaining 39 (=71%) are reasonably evenly distributed over the range ∼24–20 ka BP. This span of dates, however, is seemingly inconsistent with the layer’s well-structured planigraphy and the technotypological coherence of its assemblage, which instead point to its formation over a short period (Rogachev Reference Rogachev and Gerasimov1969; Sinitsyn et al. Reference Sinitsyn, Praslov, Svezhentsev, Sulerzhitskiy and Sinitsyn1997).

To examine this issue, we dated bones from the 1980s excavation of the second habitation complex, from which all of the previous radiocarbon dates for Layer I have come. In its composition this complex resembles the more completely excavated first complex: a line of hearths is surrounded by features interpreted as dwelling and storage pits (Figure 6). Our three dated samples came from features in different parts of the second complex (Table 1, Figure 6). Two of the dated bones bear signs of human modification (Table 1). Samples were processed using ORAU’s routine procedure. Because one of the sampled bones was a worked bone awl and may have been treated with preservatives, we included an acetone, methanol and chloroform solvent wash for this sample (OxA-26765).

Our results of 23,530 ± 170 BP, 23,260 ± 160 BP and 23,510 ± 160 BP (Table 1; Figure 5) are consistent with a short chronology for the complex, and therefore for the layer.

Kostenki 21 (Gmelinskaya)

Different material is known from Layer III of Kostenki 21 (Figure 1), which was the subject of extensive excavation in the 1960s and 70s. Whereas the site’s two upper archaeological layers yielded very few artefacts, the lowermost Layer III contained >35,000 lithic pieces, making it one of Kostenki’s major assemblages. The Layer III lithic assemblage is characterized by two point types: shouldered points, which are overall smaller and especially narrower than those in KAC assemblages, and Anosovka points. The latter have also been identified at Layer II of Kostenki 11 (Anosovka II), and a cultural link between Kostenki 21 Layer III and Kostenki 11 Layer II has been widely postulated (Rogachev and Popov Reference Rogachev and Popov1982; Lisitsyn and Dudin Reference Lisitsyn and Dudin2019; Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Germonpré, Bessudnov and Sablin2019). At Kostenki 21 Layer III, shouldered points and Anosovka points are found in separate areas (southern and northern respectively), which may reflect separate chronologically close but culturally distinct occupations (Lisitsyn Reference Lisitsyn2019; Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Germonpré, Bessudnov and Sablin2019).

Unlike Kostenki 15 and Kostenki 1, which lie in deposits equivalent to the River Don’s second terrace, Kostenki 21 is located on the Don’s first terrace. This has led to its three layers being sealed by substantial alluvial and colluvial deposits: Layer III is separated from the overlying Layer II by ∼1 m, with the uppermost Layer I a further ∼1.5 m higher. However, Kostenki 21’s location on the first terrace has also meant difficulties in high-resolution geochronological correlation with other Kostenki sites. Generally, Layer III is understood as close in age to several other layers, including Kostenki 1 Layer I and other KAC assemblages. While some have viewed Kostenki 21 Layer III as probably slightly younger than these KAC sites (Bessudnov Reference Bessudnov2019; Lisitsyn Reference Lisitsyn2019; Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Germonpré, Bessudnov and Sablin2019), their different ages cannot be confidently concluded from existing radiocarbon dates (see Appendix).

To help clarify its age we produced three new dates for Layer III of Kostenki 21. All dated samples came from the 1971 excavation of Northern Complex III (see Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Germonpré, Bessudnov and Sablin2019: fig.3): an oval concentration of archaeological remains, ∼4 m in diameter, with a hearth at its center, where Anosovka points were found. The complex’s structured planigraphy and lithic refits led Praslov and Ivanova (Reference Praslov and Ivanova1982; Ivanova Reference Ivanova1985) to view it as the remains of a dwelling structure. We also produced single dates for the overlying Layers II and I, primarily to constrain Layer III’s age. Samples were processed using ORAU’s routine procedure, including a cautionary acetone, methanol and chloroform solvent wash for the samples that were suspected to have been contaminated by conservation materials (Table 1).

Our new dates for Layer III of 21,570 ± 130 BP, 21,100 ± 130 BP and 22,570 ± 150 BP (Table 1; Figure 5) are compatible with the site’s geochronological position. However, they do not overlap statistically as a group (T’=6.54; chi-squared =3.84 with 2 degrees of freedom). It is unclear how this should be interpreted. The presence in the layer of spatially distinct assemblages means it may contain material of (observably) different ages, although the excavator’s interpretation of Northern Complex III would suggest all of the dated samples should be cotemporary. Alternatively, it is possible that the younger dates are underestimates of the samples’ ages. Irrespective of this, we can note that our results agree well with the four older of the five previous dates for the layer (see Appendix). Importantly, all of these dates are younger than our results for the KAC Kostenki 1 Layer I.

DISCUSSION

Recent bone-dating work has clarified the chronology of several Kostenki layers (Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Lisitsyn, Sablin, Barton and Higham2015, Reference Reynolds, Dinnis, Bessudnov, Devièse and Higham2017; Douka and Higham Reference Douka and Higham2017; Dinnis et al. Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Reynolds, Douka, Dudin, Khlopachev, Sablin, Sinitsyn and Higham2018, Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Reynolds, Devièse, Pate, Sablin, Sinitsyn and Higham2019a). New dates have generally been consistent within each assemblage and have aligned well with Kostenki’s geochronology. This work has shown more clearly a chronological separation of assemblages whose chronological relationships were previously unknown or unclear. The net result is a higher resolution reconstruction of Late Pleistocene occupation and a better picture of the tempo of Upper Paleolithic cultural change (Figure 2). This will facilitate more robust synchronic and diachronic inter-assemblage comparisons, and a better understanding of if, and how, assemblages are related.

The results presented here help to do just that, most notably for the Gorodtsovian Kostenki 15. Recently, Hoffecker et al. (Reference Hoffecker, Holliday, Stepanchuk and Lisitsyn2018) have proposed a functional relationship between some of Kostenki’s early non-Aurignacian assemblages, especially those classed as Gorodtsovian, and its Aurignacian ones. For Hoffecker et al., differences between them may relate to butchery events and the large horse-bone accumulations at some sites, including Kostenki 15. While site function may account for some features of the Kostenki Upper Paleolithic it cannot easily explain the relationship between its Aurignacian and Gorodtsovian assemblages. Such an explanation requires their contemporaneity, but Aurignacian material appears older.

Kostenki’s best-stratified and well-dated Aurignacian assemblage comes from Kostenki 14’s Layer in Volcanic Ash. It is currently dated to 34.5-33 ka BP (Dinnis et al. Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Reynolds, Devièse, Pate, Sablin, Sinitsyn and Higham2019a) (Figure 2). Another typically Aurignacian assemblage from Layer III of Kostenki 1 is likely to be (at least broadly) contemporary (Dinnis et al. Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Reynolds, Devièse, Pate, Sablin, Sinitsyn and Higham2019a, Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Chiotti, Flas and Michel2019b). Slightly older layers at Kostenki 14 and Kostenki 17 (Figure 2) share some attributes with Proto-Aurignacian assemblages (Dinnis et al. Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Reynolds, Devièse, Pate, Sablin, Sinitsyn and Higham2019a, Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Chiotti, Flas and Michel2019b, Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Reynolds, Pate, Sablin and Sinitsyn2020). Overall, current evidence indicates an age of ≥33 ka BP for Kostenki’s Aurignacian material.

Gorodtsovian assemblages post-date this. Only at Kostenki 14 are both found in a single stratigraphy, with the younger Gorodtsovian Layer II higher in the sequence. Gorodtsovian assemblages from Kostenki 14 Layer II, Kostenki 15 and Kostenki 12 Layer I were all found within or towards the top of the Upper Humic Bed (Rogachev and Anikovich Reference Rogachev, Anikovich, Praslov and Rogachev1982; Rogachev and Sinitsyn Reference Rogachev and Sinitsyn1982; Velichko et al. Reference Velichko, Pisareva, Sedov, Sinitsyn and Timireva2009; Sedov et al. Reference Sedov, Khokhlova, Sinitsyn, Korkka, Rusakov, Ortega, Solleiro, Rozanova, Kuznetsova and Kazdym2010), in contrast to the Kostenki 14 Aurignacian, which was found underlying it. Of all published radiocarbon dates for Gorodtsovian assemblages, the oldest are eight of 13 dates for Kostenki 14 Layer II, which range ∼29.5–28 ka BP (Sinitsyn and Hoffecker Reference Sinitsyn and Hoffecker2006; Sinitsyn Reference Sinitsyn and Bessudnov2014; Douka and Higham Reference Douka and Higham2017). This is significantly younger than the Aurignacian material at the same site. Our new results of ∼27.5–27 ka BP for the Gorodtsovian Kostenki 15 are similarly much younger. Kostenki’s Aurignacian and Gorodtsovian can therefore be separated on chronological, rather than simply functional, grounds (Figure 2).

More broadly, the range of ∼33.5–25.5 ka BP proposed by Hoffecker et al. (Reference Hoffecker, Holliday, Stepanchuk and Lisitsyn2018: 54) for a functional variant of the Aurignacian supposes a long and late Aurignacian chronology that is highly unlikely. The latest Aurignacian layers in Western Europe and in the Upper and Middle Danube regions seem to predate 29 ka BP (Jöris et al. Reference Jöris, Neugebauer-Maresch, Weninger, Street, Neugebauer-Maresch and Owen2010; Higham et al. Reference Higham2011; Dinnis et al. Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Chiotti, Flas and Michel2019b), and there is good chronostratigraphic agreement of Aurignacian-type bladelet tools between Eastern and Western Europe (Dinnis et al. Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Chiotti, Flas and Michel2019b). Furthermore, comparable (post-Aurignacian) Gravettian material in Western, Central and Eastern Europe is apparently evident by 28.5 ka BP (Jöris et al. Reference Jöris, Neugebauer-Maresch, Weninger, Street, Neugebauer-Maresch and Owen2010; Reynolds and Green Reference Reynolds and Green2019; Douka et al. Reference Douka, Chiotti, Nespoulet and Higham2020). The picture that emerges is of broad chronocultural agreement between Kostenki and the richer and better dated Aurignacian record further west. As for the rest of Europe, the very latest age for Eastern European Aurignacian material may be assumed to be ∼29 ka BP.

Our results also help clarify the chronological relationships of some of Kostenki’s younger assemblages. The new radiocarbon dates of 23.5–23 ka BP for Kostenki 1 Layer I (Table 1) are consistent with a short chronology for the layer. They support the view of the excavators and others that the layer’s well-defined habitation structures and coherent artefact assemblage represent activity over a few years or (at most) generations, rather than activity spanning several millennia (Rogachev Reference Rogachev and Gerasimov1969; Sinitsyn et al. Reference Sinitsyn, Praslov, Svezhentsev, Sulerzhitskiy and Sinitsyn1997; Praslov Reference Praslov2003).

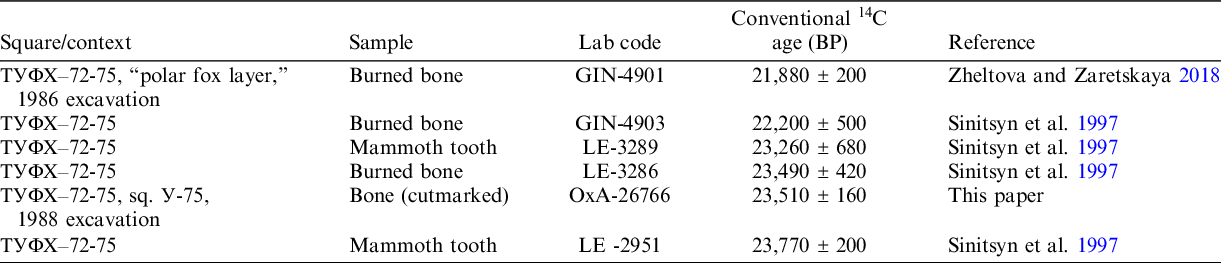

Such a conclusion is, though, counter to that of Zheltova and Zaretskaya (Reference Zheltova and Zaretskaya2018), who recently presented new dates on burnt bone for the layer ranging in age from 20,850 ± 160 BP (GIN-4892) to 22,175 ± 260 BP (GIN-4895) (Appendix 1). For them, the span of the layer’s dates is evidence for a long history of occupation and for the site having a complex, palimpsest nature. It is noteworthy that one of Zheltova and Zaretskaya’s (Reference Zheltova and Zaretskaya2018) samples (GIN-4901) came from the same feature as one of ours (OxA-26766): a dugout dwelling pit, up to 1 m deep, found across squares ТУФХ–72-75 (Figure 6). In total there are six radiocarbon dates from this feature, ranging from 21,880 ± 200 BP (GIN-4901) to 23,770 ± 200 BP (LE-2951) (Table 2). Like similar features in the layer, aspects of its layout and fill are perhaps evidence for multiple episodes of activity (Praslov et al. Reference Praslov, Rogachev, Ivanova and Popov1978; Praslov Reference Praslov1987; AS pers. obs.), but there is no reason to think this activity would span a period observable at the resolution of radiocarbon dating. In light of this, we suggest that the discrepancy between Zheltova and Zaretskaya’s (Reference Zheltova and Zaretskaya2018) dates and our own is more likely to relate to the material being dated. Burnt bone is typically low in carbon and often remaining pyrolyzed collagen cannot be separated effectively from low carbon sediments in the bone matrix. If the sediment carbon is of a different age than the residual collagen itself, erroneous ages will result. Analytical assessments of the integrity of extracted collagen are not possible when it is pyrolyzed and generally we observe that dates derived from burnt bones are usually underestimates of the true age of the sample, often substantially. We note here that of the six dates for the pit across squares ТУФХ–72-75, the two <23 ka BP are both from burnt bone (Table 2). They therefore ought to be considered likely to be problematic.

Table 2 Radiocarbon dates for material from the dugout feature ТУФХ–72-75 of Kostenki 1 Layer I (see Figure 6).

Given the excavators’ observations, problems evident in the existing corpus of radiocarbon dates, and the consistency of our new dates of ∼23.5–23 ka BP, a short chronology for Kostenki 1 Layer I is the most appropriate reading of the evidence. This is also consistent with recently produced dates of ∼23.5–23 ka BP for Kostenki’s other KAC sites (Douka and Higham Reference Douka and Higham2017; Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Dinnis, Bessudnov, Devièse and Higham2017). This includes Kostenki 18, for which the most recent age estimate of ∼23.5 ka BP (Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Dinnis, Bessudnov, Devièse and Higham2017) for the site’s child burial has been questioned (Kuzmin Reference Kuzmin2019). Kuzmin (Reference Kuzmin2019) has argued that dates of <21 ka BP for mammoth bones associated with the burial suggest our new date for the burial itself is erroneously old. Kuzmin’s (Reference Kuzmin2019) argument assumes that previous dates from bone untreated with conservation materials can be considered accurate, an assumption now well-demonstrated not to be true for bone from Kostenki (Dinnis et al. Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Reynolds, Devièse, Pate, Sablin, Sinitsyn and Higham2019a). Unlike the site’s previous dates, Reynolds et al.’s (Reference Reynolds, Dinnis, Bessudnov, Devièse and Higham2017) new radiocarbon age was produced using HYP pretreatment, which permits dating of a specific molecule, hydroxyproline, rather than collagen, which may still contain contaminant carbon (Devièse et al. Reference Devièse, Comeskey, McCullagh, Bronk Ramsey and Higham2018). As well as HYP pretreatment having a sound methodological basis (Devièse et al. Reference Devièse, Comeskey, McCullagh, Bronk Ramsey and Higham2018; Higham Reference Higham2019), studies have shown that for Upper Palaeolithic-age bones it produces demonstrably accurate results where other pretreatment methods produce those that are erroneously young (e.g., Bourrillon et al. Reference Bourrillon, White, Tartar, Chiotti, Mensan, Clark, Castel, Cretin, Higham, Morala, Ranlett, Sisk, Deviese and Comeskey2018; Dinnis et al. Reference Dinnis, Bessudnov, Reynolds, Devièse, Pate, Sablin, Sinitsyn and Higham2019a). For these reasons, Reynolds et al.’s (Reference Reynolds, Dinnis, Bessudnov, Devièse and Higham2017) age of ∼23.5 ka BP should be considered the most reliable result for the site, and therefore the only accurate one. When Kostenki 18’s previous dates are treated as unreliable, there is no reason to conclude that an age of ∼23.5 ka BP “is not in accordance with the stratigraphy of the site” (Kuzmin Reference Kuzmin2019: 1067); nothing in Kostenki 18’s stratigraphy is inconsistent with Reynolds et al.’s (Reference Reynolds, Dinnis, Bessudnov, Devièse and Higham2017) proposed age (Rogachev Reference Rogachev1953, Reference Rogachev1959).

Altogether, recent work therefore points to a short, shared chronology of ∼23.5-23 ka BP for all of Kostenki’s KAC sites (Douka and Higham Reference Douka and Higham2017; Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Dinnis, Bessudnov, Devièse and Higham2017; this paper). This chronology is also consistent with our results for Layer III of Kostenki 21. Our dates of ∼22.5-21 ka BP (Table 1, Figures 2 and 5) support a younger age than that of KAC layers. These results provide additional evidence that Kostenki 21 Layer III is contemporary with Kostenki’s other Anosovka point assemblage—Kostenki 11 Layer II—for which the older of two dates is 21,800 ± 200 BP (GIN-2531) (Rogachev and Popov Reference Rogachev and Popov1982). An age of ∼22.5-21 ka BP for these Anosovka point assemblages by extension implies a short chronological window for older KAC ones.

CONCLUSION

Kostenki’s archaeological value lies not just in its multiple and often large Upper Paleolithic assemblages, but also in the quality of the chronological data the sites provide. There is abundant dateable material connected to human activity, and the area has a well-researched geochronological framework that allows a degree of corroboration for individual radiocarbon dates. This is particularly important for the earlier part of the Upper Paleolithic, where producing consistently accurate radiocarbon dates has proved difficult. Thanks to the application of rigorous decontamination protocols, the bone dates presented here provide an improved chronology for key Kostenki sites whose precise chronology was previously unestablished or unclear.

Our new results clarify the relationships between some Kostenki sites. New dates from the Gorodtsovian Kostenki 15 are consistent with its archaeological layer deriving from a short period of activity. Importantly, these dates also clarify that it is unrelated to Aurignacian assemblages. Our results from the KAC Layer I of Kostenki 1 are similarly consistent with its accumulation over a short period. This is in line with its well-structured planigraphy and the technotypological coherence of its artefact assemblage and suggests that many of the layer’s previous radiocarbon dates are underestimates of the samples’ real ages. Importantly, our new dates for Kostenki 1 Layer I agree with recent results of ∼23.5–23 ka BP for other KAC sites at Kostenki, suggesting they together represent a relatively short-lived and culturally distinct period of occupation in the area. Further support for this interpretation comes from our slightly younger dates for culturally different material from Layer III of Kostenki 21.

Along with other recently produced dates, all of our results contribute to a refined picture of intermittent occupation over ∼20,000 14C yrs. When considered overall, this work supports the view that much of the technotypological difference between assemblages reflects chronologically distinct periods of occupation, providing an important insight into the tempo of Upper Paleolithic cultural change.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the Leverhulme Trust (AHOB3 and RPG-2012-800). We thank the staff of the ORAU past and present for their careful laboratory work. We also thank the reviewers and Editor-in-Chief for their comments. AB and AS acknowledge Russian Science Foundation grant numbers 20-78-10151 and 18-78-00136, and Russian Foundation of Basic Research grant numbers 18-39-20009, 18-00-00837 and 20-09-00233. We also acknowledge the participation of IHMC RAS (state assignment 0184-2019-0001) and ZIN RAS (state assignment АААА-А19-119032590102-7). We thank the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) for supporting the Oxford node of the National Environmental Isotope Facility (NEIF).

APPENDIX

Previous radiocarbon dates for Kostenki 15, Kostenki 1 Layer I and Kostenki 21 Layer III.