Introduction

A defining characteristic of living organisms is their ability to reproduce their genetic information. To ensure that each daughter cell inherits a full genome during mitotic cell division, the DNA forms a highly condensed structure – the metaphase chromosome (Alberts et al., Reference Alberts, Johnson, Lewis, Raff, Roberts and Walter2002; Hirano, Reference Hirano2015). Mitotic chromosomes are a complex compound material composed of DNA and proteins, with an intriguing three-dimensional structure that we are only slowly beginning to understand. Mitosis is precisely controlled with a sequential progression of key steps. First, during prophase, the chromatin fibers of the duplicated chromosomes (called sister chromatids) are disentangled from each other. These chromatin fibers consist of the DNA, containing the genetic information, wound around histone protein complexes. Subsequently, at prometaphase, the nuclear envelope is disrupted and the sister chromatids are attached to the mitotic spindle. In metaphase, this microtubule structure then arranges the chromosomes in the middle between the two spindle poles. This ensures faithful segregation between the two daughter cells when the sister chromatids are separated during the subsequent anaphase. The mitotic spindle pulls the separated chromosomes into the nascent daughter cells, where new nuclei are formed during telophase before cell division is completed by the cytokinesis (Alberts et al., Reference Alberts, Johnson, Lewis, Raff, Roberts and Walter2002; Hirano, Reference Hirano2015).

During prophase and prometaphase, the chromosome undergoes a substantial compaction, a process also known as chromosome condensation, in order to facilitate the transport into the daughter cells and also support chromosome disentanglement (Alberts et al., Reference Alberts, Johnson, Lewis, Raff, Roberts and Walter2002; Hirano, Reference Hirano2015; Gibcus et al., Reference Gibcus, Samejima, Goloborodko and Dekker2018). The condensation is so efficient that DNA strands with a contour length of several centimeters are compressed into condensed chromosomes with a length of a few micrometers, a reduction in length by four orders of magnitude. Chromosome condensation does not only induce spatial compaction of the chromosomes, but also profoundly changes their internal structure and physical properties (Gibcus et al., Reference Gibcus, Samejima, Goloborodko and Dekker2018). Therefore, insights into the structure and physical characterization of mitotic chromosomes are not only critical to understand the genetic organization, but also necessary to uncover how crucial processes such as faithful chromosome segregation are accomplished. Considering the fundamental relevance of mitosis, it is no surprise that spatial or temporal mistuning can lead to cell death or genetic defects, like aneuploidy (Potapova and Gorbsky, Reference Potapova and Gorbsky2017).

At the fundamental level, chromosome condensation and separation represent biomechanical problems: during chromosome condensation, the DNA needs to be compressed below its entropically favorable end-to-end distance; during separation, the two sister chromatids need to be topologically disentangled; during anaphase, they have to be transported to the spindle poles. The forces necessary to induce those dynamic procedures are generated exogenously by the mitotic spindle or endogenously by protein–protein and protein–DNA interactions and molecular motors. However, the forces involved in mitosis are only poorly understood. Moreover, the force responses and, specifically, the elastic properties of chromosomes are of importance because they might provide additional insights into the chromosome structure.

Therefore, it comes as no surprise that there is substantial interest in the characterization of the mechanical properties of mitotic chromosomes. While mitosis has been studied with a plethora of different methods, we are only beginning to understand the local structure and the global mechanics of mitotic chromosomes. Our lack of knowledge of the structural details of mitotic chromosomes is mainly due to the chromosomes' relatively high density and small size. The small size requires the use of optical or electron microscopy to elucidate the structure, but these methods are impeded by the high density of the chromosomes. Recent advances in genomics, computational techniques, and super-resolution imaging have uncovered many new details of mitotic chromosomes, that have led to the proposal of a consistent chromatin loop model for mitotic chromosome compaction driven by structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) protein complexes (Gibcus et al., Reference Gibcus, Samejima, Goloborodko and Dekker2018; Walther et al., Reference Walther, Hossain, Politi and Ellenberg2018). On the other hand, a better understanding of how the mechanical properties emerge and are preserved in mitotic chromosomes might provide us with a completely different and independent prospect to establish a structural model of mitotic chromosomes. Although the first experiments to characterize the mechanical properties of mitotic chromosomes have been performed long ago (Nicklas, Reference Nicklas1965), recent advances in our understanding of the structure of mitotic chromosomes (Gibcus et al., Reference Gibcus, Samejima, Goloborodko and Dekker2018; Walther et al., Reference Walther, Hossain, Politi and Ellenberg2018) have prompted us to revisit and review the direct measurements of the mechanical properties of mitotic chromosomes. We will first introduce the current understanding of the structure of mitotic chromosomes. Next, we will discuss techniques used to probe the mechanical properties of chromosomes, the results obtained, and attempt to draw a connection between the mechanical characterization of mitotic chromosomes and their complex structure.

Current structural model for mitotic chromosomes

Although our understanding of the structure of mitotic chromosomes is still far from complete, recent advances (Gibcus et al., Reference Gibcus, Samejima, Goloborodko and Dekker2018; Walther et al., Reference Walther, Hossain, Politi and Ellenberg2018) have provided compelling evidence for the radial-loop model first proposed by Paulson and Laemmli (Reference Paulson and Laemmli1977) and led to a consistent model for chromatin organization in mitotic chromosomes. In addition, a model is emerging describing how this structure can be formed by loop extrusion (Alipour and Marko, Reference Alipour and Marko2012; Goloborodko et al., Reference Goloborodko, Marko and Mirny2016b; Terakawa et al., Reference Terakawa, Bisht, Eeftens, Dekker, Haering and Greene2017; Ganji et al., Reference Ganji, Shaltiel, Bisht and Dekker2018). In the following, we will briefly introduce this model and discuss open questions in the field. For a review specifically focusing on this topic, see Batty and Gerlich (Reference Batty and Gerlich2019), Takahashi and Hirota (Reference Takahashi and Hirota2019), and Zhou and Heald (Reference Zhou and Heald2020).

For a long time, it had been believed that the formation of mitotic chromosomes relies on hierarchical chromatin folding, with the chromatin forming a distinct 30 nm fiber. However, electron micrographs of mitotic chromosomes in vivo do not support this theory, and instead show a disordered chromatin structure without any higher-order organization (Eltsov et al., Reference Eltsov, MacLellan, Maeshima, Frangakis and Dubochet2008; Nishino et al., Reference Nishino, Eltsov, Joti and Maeshima2012). The role of histone interactions on chromosome compaction and their organization and dynamics in the mitotic chromosome are debated. Although it is generally accepted that nucleosome interactions contribute to chromosome compaction, different results support contradicting models ranging from interdigitated nucleosome stacks to a polymer melt of chromatin (Eltsov et al., Reference Eltsov, MacLellan, Maeshima, Frangakis and Dubochet2008; Chicano et al., Reference Chicano, Crosas, Otón, Melero, Engel and Daban2019). A discussion of these different results can be found in Fierz (Reference Fierz2019).

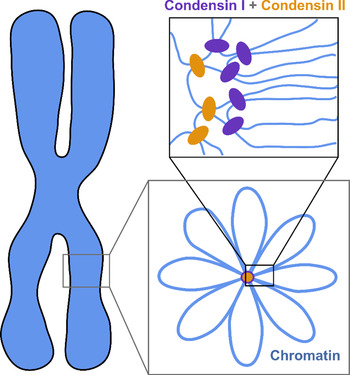

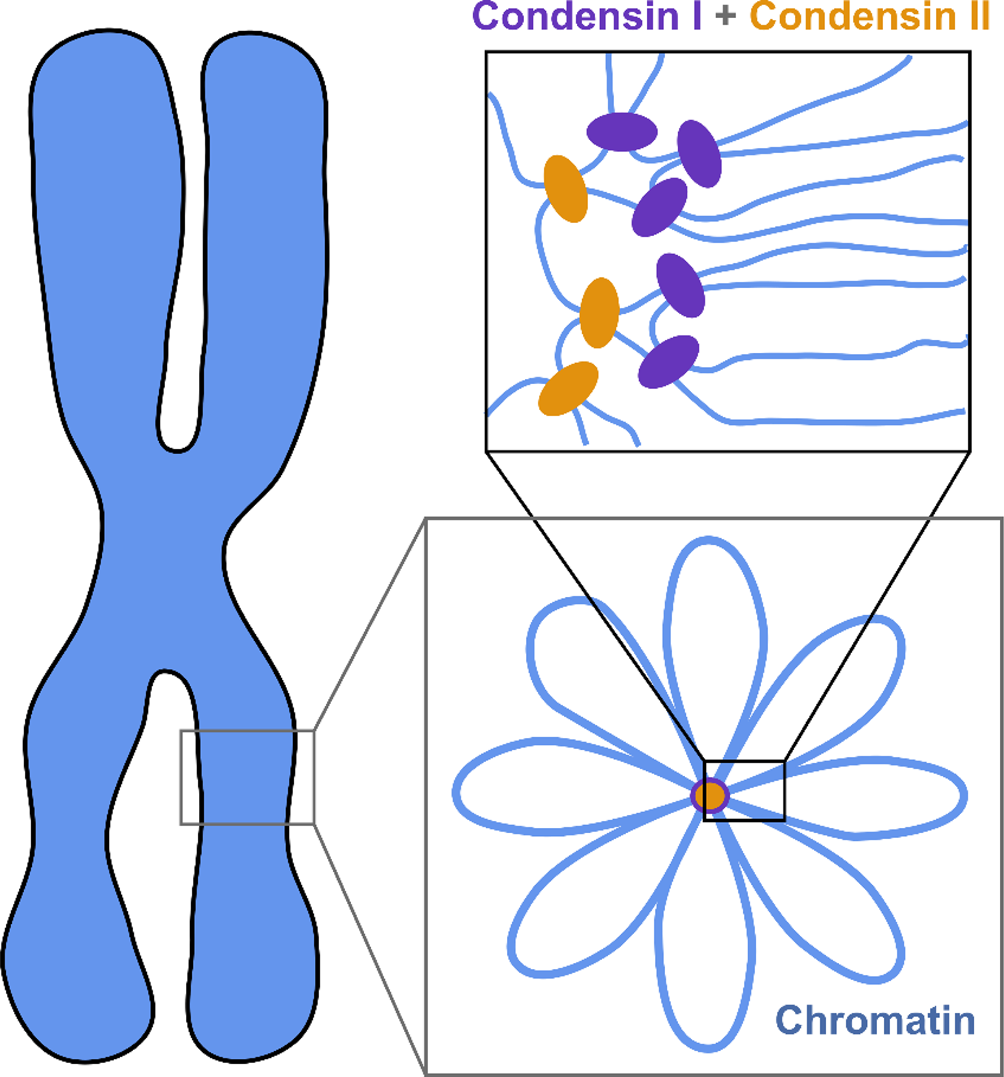

The current understanding of the structure of mitotic chromosomes is summarized in the radial-loop model: the chromatin fiber in the mitotic chromosome forms loops emanating from a central scaffold composed of condensin protein complexes (Fig. 1) (Gibcus et al., Reference Gibcus, Samejima, Goloborodko and Dekker2018; Walther et al., Reference Walther, Hossain, Politi and Ellenberg2018). This chromatin organization has been described as the bottle-brush structure (Fierz, Reference Fierz2019). To allow for even more efficient compaction, a nested-loop structure is formed by the concerted action of condensin I, which is located further away from the center of the scaffold, and condensin II, which binds more stably and closer to the center of the scaffold. These nested loops are formed through loop extrusion by the condensin complexes, which exhibit motor activity and are believed to pull the DNA through the ring-shaped complex to form loops (Kawamura et al., Reference Kawamura, Pope, Christensen and Marko2010; Alipour and Marko, Reference Alipour and Marko2012; Goloborodko et al., Reference Goloborodko, Marko and Mirny2016b; Terakawa et al., Reference Terakawa, Bisht, Eeftens, Dekker, Haering and Greene2017; Ganji et al., Reference Ganji, Shaltiel, Bisht and Dekker2018). The size of the larger loops has been reported to be 400–450 kb, while that of the smaller, nested loops is 70–80 kb (Gibcus et al., Reference Gibcus, Samejima, Goloborodko and Dekker2018; Walther et al., Reference Walther, Hossain, Politi and Ellenberg2018). This model is independently supported by super-resolution microscopy of SMC proteins in HeLa cells and by Hi-C conformation capture data (Gibcus et al., Reference Gibcus, Samejima, Goloborodko and Dekker2018; Walther et al., Reference Walther, Hossain, Politi and Ellenberg2018).

Fig. 1. The radial-loop model. The chromatin fiber forms loops emerging from a central scaffold composed of condensin I and II. To achieve maximal compaction two tiers of nested loops are formed. Figure adapted from Gibcus et al. (Reference Gibcus, Samejima, Goloborodko and Dekker2018). Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

Even though a clear picture of the chromatin organization within mitotic chromosomes is starting to emerge, we are still only starting to fully understand the structure and dynamics of the mitotic chromosome. Open questions include: What is the microscopic shape and structure of the condensin II scaffold? Can individual loops established by condensins be visualized in the chromosome? What is the structure of the scaffold at the ends or in the center of the chromosome? What is the role of other proteins like topoisomerase (topo) II? Although topo II is known to be required for correct chromosome formation, its contribution to the maintenance of the chromosome structure remains elusive (Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Zhang, Barisic, Kalitsis and Hudson2020).

Furthermore, a large gap exists in our understanding of DNA organization: On the one hand, molecular mechanisms were precisely characterized in vitro based on experiments with double-stranded naked DNA and isolated proteins (Terakawa et al., Reference Terakawa, Bisht, Eeftens, Dekker, Haering and Greene2017; Ganji et al., Reference Ganji, Shaltiel, Bisht and Dekker2018). On the other hand, the structure of the chromosome has been studied in vivo on whole mitotic chromosomes in the complex surrounding of the cell (Gibcus et al., Reference Gibcus, Samejima, Goloborodko and Dekker2018; Walther et al., Reference Walther, Hossain, Politi and Ellenberg2018). However, the connection between these two different length scales is not fully resolved, yet. While simulations have provided some insights, for example, on how loop extrusion gives rise to the structure of the chromosome (Goloborodko et al., Reference Goloborodko, Imakaev, Marko and Mirny2016a), experimental studies are still missing. One way to narrow this gap is to make use of isolated whole chromosomes, which allows precise manipulation of the chromosome, while maintaining almost all of its complexity.

Mechanical characterization of mitotic chromosomes

Methods to study the mechanics of mitotic chromosomes

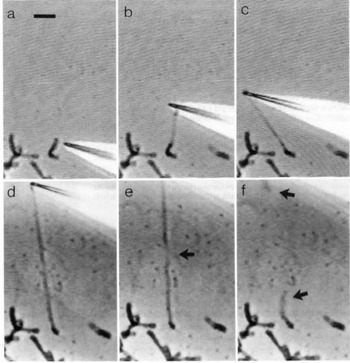

Direct manipulation of mitotic chromosomes has initially been performed with microdissection methods using micropipettes or microneedles, allowing access to the elastic properties of chromosomes. In their pioneering work, Nicklas et al. used a microneedle to pin chromosomes in living grasshopper spermatocytes during anaphase (Nicklas and Staehly, Reference Nicklas and Staehly1967; Nicklas, Reference Nicklas1983). From their first qualitative study, they were able to conclude that chromosomes are attached to the mitotic spindle, which was still under debate at that time (Nicklas and Staehly, Reference Nicklas and Staehly1967). In a second study, they used calibrated microneedles, which allowed them to directly measure the force exerted on the chromosome from the bending of the microneedle (Nicklas, Reference Nicklas1983). Nicklas measured the force required to stop the movement of the chromosome and was thus able to estimate the pulling force of the mitotic spindle to be on the order of 100 pN. By characterizing the shape of the bent chromosomes, he could furthermore infer elastic parameters and found that chromosomes showed no sign of plasticity (Nicklas, Reference Nicklas1983). Claussen et al. were the first to use mechanical manipulation to study isolated chromosomes (from human lymphocytes) under controlled conditions (Fig. 2) (Claussen et al., Reference Claussen, Mazur and Rubtsov1994). The chromosomes were adhered to a surface and manipulated with a microneedle. The most striking finding in their study was the remarkable extensibility of chromosomes (Claussen et al., Reference Claussen, Mazur and Rubtsov1994). In order to manipulate chromosomes (isolated from cultured newt lung cells) with higher precision at their telomeric ends, Houchmandzadeh et al. introduced the use of micropipette aspiration, a strategy that was later widely adopted (Houchmandzadeh et al., Reference Houchmandzadeh, Marko, Chatenay and Libchaber1997).

Fig. 2. Pioneering experiments by Claussen et al. (a) Isolated mitotic chromosomes were placed on a glass slide and (b–f) stretched by a micropipette to multiples of its initial length. (e) The arrow indicated the position at which the chromosome breaks. (f) Both chromosome ends (marked by arrows) are contracted after been torn. Already these early experiments demonstrate the intriguing mechanical properties of chromosomes. Figure from Claussen et al. (Reference Claussen, Mazur and Rubtsov1994). Copyright© 1994 Karger Publishers, Basel, Switzerland.

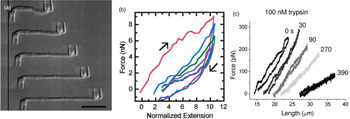

Marko and coworkers developed a technique to increase the force resolution by aspiring the chromosome on both ends: A stiff micropipette on one end allowed manipulation of the chromosome, while the force response was measured on the other end of the chromosome by using a second, softer micropipette with a known force deflection constant as a force transducer (Fig. 3) (Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Eroglu, Chatenay and Marko2000). Using this approach, they could show that mitotic newt chromosomes display a reversible elasticity at extensions over fivefold, requiring 1 nN of force to be stretched to two times their native length. Poirier et al. then introduced a technique that allowed to alter environmental parameters such as buffer conditions or enzymatic digesting in situ by microinjection from a third micropipette (Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Monhait and Marko2002b; Poirier and Marko, Reference Poirier and Marko2002b). With this approach, they showed that chromosomes do not have a continuous protein scaffold. Almagro et al. used antibodies to attach chromosomes assembled from Xenopus egg extract to micropipettes via specific target proteins (Almagro et al., Reference Almagro, Riveline, Hirano, Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2004). Not only did they find a different elastic response of the chromosome than in the earlier aspiration experiments, they also observed different mechanical responses depending on the target protein, which they attributed to differences in elasticity of different chromosomal domains (Almagro et al., Reference Almagro, Riveline, Hirano, Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2004).

Fig. 3. Mechanical characterization of mitotic chromosomes by micropipette aspiration. (A) Differential interference contrast images of a mitotic chromosome clamped between two glass micropipettes. Scale bar = 10 μm. (B) Force extension curves of mitotic chromosomes stretched to large extensions. A linear regime is followed by slight stress softening. Consecutive pulling cycles to large extensions are not fully reversible. (C) Force extension curves of mitotic chromosomes incubated with 100 nM Trypsin at different time points after incubation. The chromosome is dramatically softening but does not disintegrate. Figures adapted from Poirier et al. (Reference Poirier, Eroglu, Chatenay and Marko2000, Reference Poirier, Eroglu and Marko2002a) and Pope et al. (Reference Pope, Xiong and Marko2006).

In a completely different approach, atomic force microscopy (AFM) can be used to map the elasticity of chromosomes adhered to a surface. In a first study, the viscoelastic properties of rehydrated metaphase chromosomes have been studied using AFM (Fritzsche and Henderson, Reference Fritzsche and Henderson1997). One advantage of AFM is that it allows to generate a map of elastic properties by scanning over the chromosome, which unveiled large inhomogeneities in the Young's modulus with variations over one order of magnitude (Fig. 4) (Jiao and Schäffer, Reference Jiao and Schäffer2004; Nomura et al., Reference Nomura, Hoshi, Fukushi, Ushiki, Haga and Kawabata2005).

Fig. 4. Mechanical characterization of mitotic chromosomes by AFM. Force-distance curves allow to simultaneously produce a map of the height (left, height above the substrate) and stiffness (right, Young's modulus). The stiffness of adsorbed chromosomes was much higher than from stretching experiments and was very inhomogeneous. Figure from Nomura et al. (Reference Nomura, Hoshi, Fukushi, Ushiki, Haga and Kawabata2005). Copyright (2005) The Japan Society of Applied Physics.

Mechanical properties of mitotic chromosomes

Already in the early qualitative studies, it was noted that chromosomes are very soft while having remarkable extensibility and durability, meaning they can be stretched to multiples of their initial length (Nicklas and Staehly, Reference Nicklas and Staehly1967; Nicklas, Reference Nicklas1983; Claussen et al., Reference Claussen, Mazur and Rubtsov1994). The later quantitative studies support this early characterization, but draw a more elaborate picture. The mechanical response of stretched chromosomes was found to be characterized by two regimes, depending on the degree of stretching. In a first regime, the response is linear within the resolution of the experiments (Figs 3B and C) (Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov, Reference Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2000; Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Eroglu, Chatenay and Marko2000, Reference Poirier, Eroglu and Marko2002a; Almagro et al., Reference Almagro, Riveline, Hirano, Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2004). In this regime, the stretching is also reversible (Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Eroglu, Chatenay and Marko2000). At large forces and extensions, a second regime is reached where the chromosomes soften and unfold irreversibly (Fig. 3B) (Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov, Reference Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2000; Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Eroglu, Chatenay and Marko2000). Depending on the species and the exact experimental configuration, softening and irreversible unfolding were observed at forces ranging from 2 to 6 nN and extensions ranging from 2 to 5 times the initial length (Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov, Reference Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2000; Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Eroglu, Chatenay and Marko2000). When the chromosome is stretched even further to relative elongations of 30 times the initial length, the force reaches a plateau around 20 nN, which is accompanied by dramatic changes in the morphology of the chromosome. These basic observations already support the hypothesis that mitotic chromatids are held together by chromatin tethering elements and that the chromatin tends to disperse as those elements are broken.

Below we review some characteristic elastic parameters of mitotic chromosomes such as the Young's modulus and the bending modulus and show how they have promoted the understanding of the mechanical properties and more importantly how they are connected to the spatial structures of mitotic chromosomes.

The Young's modulus (E) is one of the most important elastic parameters and is very sensitive to changes in the structure of the material. It is defined as the proportionality factor between stress (the applied force per unit area) and strain (the normalized length change) and has the dimension of pressure. The simultaneous measurement of the length of the chromosome and the force applied on the chromosome allows the determination of the Young's modulus of chromosomes from stretching experiments (Fig. 3). Importantly, considering the rate at which chromosomes come to mechanical equilibrium while being stretched or after stress is released, the stretch and release rate should not be faster than roughly 0.1 μm/s (Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Eroglu, Chatenay and Marko2000). These measurements support the initial impression that chromosomes are very soft with Young's modulus reaching from 100 to 1000 Pa (Nicklas, Reference Nicklas1983; Houchmandzadeh et al., Reference Houchmandzadeh, Marko, Chatenay and Libchaber1997; Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov, Reference Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2000; Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Eroglu and Marko2002a; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Kawamura and Marko2011, Reference Sun, Biggs, Hornick and Marko2018). It should be noted that for different samples and measurement techniques, a rather wide range of elasticities has been obtained. For example, the mean E of human mitotic chromosome (reported as 400 ± 20 Pa (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Kawamura and Marko2011) and 440 ± 50 Pa (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Biggs, Hornick and Marko2018)) is significantly lower than that of newt chromosomes (1000 ± 200 Pa (Houchmandzadeh et al., Reference Houchmandzadeh, Marko, Chatenay and Libchaber1997)). This difference might point to different chromatin structures for chromosomes of different species. However, differences between different chromosomes of the same species have been reported to be as large as the difference between species (Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Eroglu and Marko2002a).

For a proper determination of the Young's modulus, it is required to know or determine the diameter of the chromosome. Furthermore, the assumption is made that the chromosome is a homogeneous material, an assumption that is not well supported. To sidestep these aspects, several studies have reported the stretch modulus (the slope of the force-strain curve as force per unit strain), which is sometimes also referred to as the doubling force: the force at which the length of the chromosome is two times its initial length. Similar to the Young's modulus, reported values for the stretch modulus fall in a large range from 100 up to 1000 pN (Nicklas, Reference Nicklas1983; Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Nemani, Gupta, Eroglu and Marko2001; Almagro et al., Reference Almagro, Dimitrov, Hirano, Vallade and Riveline2003, Reference Almagro, Riveline, Hirano, Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2004; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Kawamura and Marko2011). Remarkably, the reported values of the stretch modulus strongly depend on the method to attach the chromosome to the pulling apparatus: When anti-histone antibodies were used to attach the chromosome, the stretch modulus was as low as 30 pN, while anti-SMC antibodies resulted in a sixfold increased stretch modulus of around 180 pN (Almagro et al., Reference Almagro, Riveline, Hirano, Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2004). These observations provide additional evidence for the inhomogeneity of the chromosomal structure (Almagro et al., Reference Almagro, Riveline, Hirano, Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2004).

Compared to these stretching experiments, AFM indentation experiments measured dramatically larger Young's modulus for human mitotic chromosomes (E = 0.39 MPa (Jiao and Schäffer, Reference Jiao and Schäffer2004) and E = 5–50 kPa (Nomura et al., Reference Nomura, Hoshi, Fukushi, Ushiki, Haga and Kawabata2005), Fig. 4). One explanation is that the chromosomes had been dehydrated and stored for an extended time before rehydration (Jiao and Schäffer, Reference Jiao and Schäffer2004). Furthermore, adhesion to the underlying substrate might have led to the flattening and stiffening of the chromosome. Still, the dramatic difference of several orders of magnitude emphasizes again that the understanding of the nature of these mechanical properties is still developing.

The bending modulus (B) describes the resistance of a material to bending and can be derived (among other techniques) from the thermal fluctuation spectrum of a chromosome. The bending modulus is defined as the energy required to bend a thin rod along a circle and has a dimension of energy multiplied by length. For chromosomes assembled from Xenopus egg extract, a bending modulus of 1.2 × 10−26 J⋅m was observed (Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov, Reference Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2000). By contrast, a later study reported much stiffer bending resistances of ~10−22 J⋅m for newt and ~10−23 J⋅m for Xenopus chromosomes (Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Eroglu and Marko2002a). This difference might be explained by different chromatin structures or different protein compositions of in vivo somatic and egg-extract embryonic chromatids (Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Eroglu and Marko2002a).

Later analysis of individual Xenopus mitotic chromosome showed that the bending modulus of the chromosome is not constant along its length. The chromosome is assumed to be formed of long parts of low B connected by regions of higher B (Almagro et al., Reference Almagro, Dimitrov, Hirano, Vallade and Riveline2003).

Dynamic measurements of specific elastic parameters, such as stress relaxation, can provide important insights into the dynamics of mitotic chromosomes. In this type of experiment, the mechanical properties of mitotic chromosomes are measured in a time-dependent manner, which then allows to understand the viscoelasticity of the chromosomes. One typical way to perform these experiments is to perform a step-wise elongation and then monitor the force relaxation. For newt chromosomes, the force was measured to relax exponentially with a relaxation time of ~2 s after an elongation to less than 3× the native length (Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Nemani, Gupta, Eroglu and Marko2001). This relaxation was explained in terms of the disentanglement dynamics of ~80 kb chromatin loops based on structural data (Paulson and Laemmli, Reference Paulson and Laemmli1977). Furthermore, an interesting feature of mitotic chromosomes is that below a characteristic length scale, dissipation can dominate over hydrodynamic friction relaxation time, making the bending mode relaxation time τ independent of the wave number q. This is distinct from the usual result τ~1/q 4 obtained when external hydrodynamic damping dominates. The q-independent relaxation times were considered to be associated with internal friction originating from either relatively large-scale, slow conformational rearrangements of the filament interior, or with hydrodynamic dissipation associated with flow through gel pores (Poirier and Marko, Reference Poirier and Marko2002a).

Multi-parameter analysis of the elastic properties, such as simultaneous measurements of the Young's modulus and the bending modulus, can give more detail into the structure of chromosomes. For example, Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov reported that the measured bending modulus (1.2 × 10−26 J⋅m) is 2000 times lower than the prediction from elastic beam theory using the experimentally determined Young's modulus (1100 Pa) (Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov, Reference Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2000). These results led to a structural model that the mitotic chromosomes are formed of one or a few thin rigid elastic axes surrounded by a soft envelope. However, in a later study, Poirier et al. measured the spontaneous thermal bending fluctuation and stretching elasticity on the same chromosome and found that the measured bending rigidity and stretching modulus are consistent with those expected for a simple elastic rod (Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Eroglu and Marko2002a). This observation agrees with an internal structure that is essentially homogeneous across the chromosome cross-section. This is in contrast to the variation of the bending modulus along the chromosome length reported by Almagro et al. (see above) (Almagro et al., Reference Almagro, Dimitrov, Hirano, Vallade and Riveline2003). Moreover, considering the loading-rate dependency of the stretching modulus of the SMC-rich region, Almagro et al. concluded that the chromosomal organization was better explained as a copolymer composed of an inner rigid core exhibiting viscoelasticity surrounded by an elastic, soft envelope (Almagro et al., Reference Almagro, Dimitrov, Hirano, Vallade and Riveline2003). Therefore, the chromosome cannot be considered to be homogeneous in both axial and lateral dimensions. This inhomogeneity was confirmed by the mapping of elasticity of chromosomes by AFM (Nomura et al., Reference Nomura, Hoshi, Fukushi, Ushiki, Haga and Kawabata2005).

Strikingly, the mechanical properties of the mitotic chromosome are very distinct from the mechanical properties of its building blocks, like double-stranded DNA or individual chromatin fibers. At low forces, the stretch response of both DNA and chromatin is dominated by entropic forces arising from the reduction of conformational space upon extension. These forces are routinely modeled using the worm-like chain model (Bustamante et al., Reference Bustamante, Marko, Siggia and Smith1994; Brower-Toland et al., Reference Brower-Toland, Smith, Yeh, Lis, Peterson and Wang2002). At higher forces, double-stranded DNA shows the characteristic overstretching transition, which leads to a force-plateau at ~65 pN, where the DNA melts or undergoes a structural transition under the impact of the applied force (Cluzel et al., Reference Cluzel, Lebrun, Heller and Caron1996; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Cui and Bustamante1996; Gross et al., Reference Gross, Laurens, Oddershede, Bockelmann, Peterman and Wuite2011). When an isolated chromatin fiber is stretched, a characteristic plateau around 20 pN is observed, which shows discrete steps indicating unwrapping of the histone complexes (Cui and Bustamante, Reference Cui and Bustamante1999; Brower-Toland et al., Reference Brower-Toland, Smith, Yeh, Lis, Peterson and Wang2002). Besides these natural occurring building blocks, there are also minimal model systems for DNA condensation that have been mechanically characterized. These include DNA condensation by polyamines (Broek et al., Reference Broek, Noom, Mameren, Battle, Mackintosh and Wuite2010) or polyaminoamide dendrimers (Ritort et al., Reference Ritort, Mihardja, Smith and Bustamante2006) as simplified models of the basic unit of chromatin organization, DNA-histone complexes. In both systems, a characteristic force plateau at very low forces of a few pN (~5 pN for polyamines and ~10 pN for polyaminoamide dendrimers) and a large hysteresis between the pulling and relaxation cycles (Ritort et al., Reference Ritort, Mihardja, Smith and Bustamante2006; Broek et al., Reference Broek, Noom, Mameren, Battle, Mackintosh and Wuite2010) occur. Such low force plateaus, indicative of conformational changes, are notably not observed in the stretching of mitotic chromosomes (Fig. 3). This indicates that in the complexity of a whole chromosome, such conformational changes do not play a role or average out.

More quantitatively, the several hundreds of pN stretch modulus of mitotic chromosomes appear to be similar to that of bare DNA of ~1500 pN (Gross et al., Reference Gross, Laurens, Oddershede, Bockelmann, Peterman and Wuite2011). These stretch moduli are, however, orders of magnitude larger than the 5 pN stretch modulus of chromatin fibers (Cui and Bustamante, Reference Cui and Bustamante1999). Assuming the most simple model of chromatin fibers arranged in parallel, such that their stretch moduli are additive, 20–200 parallel chromatin strands would be needed to explain the stretch modulus of mitotic chromosomes. This, however, does not take into account how forces are transmitted through the chromosome and the impact is of the SMC proteins on the mechanical properties of chromosomes.

What determines the mechanical properties of mitotic chromosomes?

How can the mechanical characterization of mitotic chromosomes be used to elucidate their structure and inversely, how does the structure determine the mechanical characteristics of mitotic chromosomes? It is so far not clear what happens on a structural level during the stretching of mitotic chromosomes, and what structural features give rise to the remarkable mechanical properties, like its extensibility and the low stiffness. However, there still exist ways to relate the structure and mechanical properties of mitotic chromosomes. Since chromatid division is inherently a mechanical process, the mechanical properties of mitotic chromosomes are important for their function. Therefore, it is of great interest to understand how the mechanical properties of chromosomes emerge from their structure.

Effect of unspecific biochemical modifications

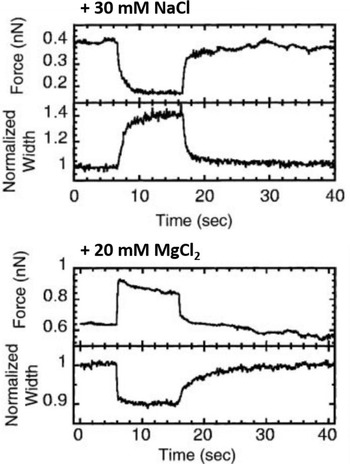

A relatively straightforward idea to connect structure and mechanical properties is to induce biochemical or chemical modifications and use elasticity measurements to probe their effect on the chromosome. An overview of different manipulations of this sort and their effect on the mechanical properties of chromosomes can be found in Table 1. Using such an approach, the hypothesis of a solid, continuous protein scaffold inside the mitotic chromosome was tested by mechanical characterization of chromosomes swollen by changes in the ion concentration (Fig. 5) (Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Monhait and Marko2002b), based on the known effect that high ion concentration can induce rapid dispersion of the mitotic chromosome (Paulson and Laemmli, Reference Paulson and Laemmli1977). In these stretching experiments, a low concentration of NaCl (30 mM) led to a decrease in tension and an increase in chromosome size. High concentrations of NaCl (500 mM) or MgCl2 (300 mM) had a similar, but even more pronounced effect. In contrast, 10 mM of divalent cations (MgCl2 and CaCl2) or 40 mM trivalent Co3+ cations induced a very rapid and reversible increase in tension and a shrinking of the chromosomes. In particular, the softening and elongation that was observed after chromosome decondensation suggests that the load-bearing element in the chromosome is not completely composed of proteins but also includes DNA. When the salt concentration was changed back to the starting conditions, the initial mechanical properties were recovered. The reversibility of the rapid ion-driven unfolding and refolding indicates that the mitotic chromosome does not have a highly ordered structure. Instead, this behavior can be explained by a relatively loose organization of the chromatin fibers, similar to a crosslinked polyelectrolyte network.

Fig. 5. Effect of chromosome decondensation by addition of 30 mM NaCl (top) or hypercondensation by addition of 20 mM MgCl2 (bottom). The plots show the time series of the force the chromosome supports and the width of the chromosome, normalized to the initial width. Changes in the buffer composition after approximately 5 s led to a rapid decrease or increase of the force that was fully reversible. At the same time, the chromosome width showed changes in the opposite direction. Figure adapted from Poirier et al. (Reference Poirier, Monhait and Marko2002b). Copyright© 2002 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

Table 1. Effect of (bio-)chemical modifications of the mechanical properties of mitotic chromosomes

Another important finding from this type of experiment was that the chromosome has no continuous protein backbone. This result was obtained by comparing the effect of protein digestion with that of DNA cutting (Poirier and Marko, Reference Poirier and Marko2002b; Almagro et al., Reference Almagro, Riveline, Hirano, Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2004; Pope et al., Reference Pope, Xiong and Marko2006; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Kawamura and Marko2011). Several studies have found independently that cutting the DNA of a clamped chromosome, for example, with DNAse or restriction enzymes, ultimately leads to the disintegration of the chromosome (Poirier and Marko, Reference Poirier and Marko2002b; Almagro et al., Reference Almagro, Riveline, Hirano, Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2004; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Kawamura and Marko2011). In contrast, protein digestion with trypsin or proteinase K usually leads to dramatic softening but does not lead to the disintegration of the chromosomes (Fig. 2C) (Almagro et al., Reference Almagro, Riveline, Hirano, Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2004; Pope et al., Reference Pope, Xiong and Marko2006; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Kawamura and Marko2011). Therefore, the mechanical integrity of the metaphase chromosome is due to DNA itself and not a continuous protein scaffold. Nuclease digestion has also been observed to impact the reversibility of chromosome stretching: Newt chromosomes could be repeatedly extended and retracted without any change in elastic response before nuclease digestion (Poirier and Marko, Reference Poirier and Marko2002b). By contrast, after 90 s of digestion, repeated extension–retraction cycles were no longer reversible, with the force needed to double chromosome length dropping with each successive extension–retraction cycle. Finally, chromosomes were found to be completely disintegrated after 200 s digestion (Poirier and Marko, Reference Poirier and Marko2002b). Furthermore, the mean space between the chromatin crosslinking elements was estimated to be ~15 kb from the digestion results using restriction enzymes with different recognition sequences (Pope et al., Reference Pope, Xiong and Marko2006). This is considerably smaller than the loop size of 70–80 kb estimated from structural data (Gibcus et al., Reference Gibcus, Samejima, Goloborodko and Dekker2018; Walther et al., Reference Walther, Hossain, Politi and Ellenberg2018). Treatment with reducing agents was found to dramatically soften the chromosome (Eastland et al., Reference Eastland, Hornick, Kawamura, Nanavati and Marko2016). However, this non-specific approach did not allow deciphering of the contribution of different proteins since numerous proteins were equally affected.

Effect of biochemical modifications of SMC proteins

A very promising approach to get more detailed structural information is the targeted removal of specific proteins. Due to the added experimental complexity, however, only a few examples of this strategy exist (Almagro et al., Reference Almagro, Riveline, Hirano, Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2004; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Biggs, Hornick and Marko2018). The main difficulty for these experiments is that all major SMC proteins are critical for cell division, making it very difficult to generate viable knock-out cell lines. Despite these challenges, targeted modification of proteins was successfully used to address the contributions of nucleosome interactions on the structure of chromosome by using epigenetic drugs. It was shown that post-translational modifications of histones, specifically hypermethylation, increases the stiffness of chromosomes, which is direct evidence for a substantial contribution of histone interactions to the mechanical properties of mitotic chromosomes and presumably also on chromosome compaction (Biggs et al., Reference Biggs, Liu, Stephens and Marko2019). The organization and dynamics of histones in the mitotic chromosome, however, remain unclear (Fierz, Reference Fierz2019).

According to the radial-loop model, the main structural scaffold of mitotic chromosomes consists of condensin complexes, which therefore would also be expected to govern the mechanical response. Indeed, a dramatic decrease of the Young's modulus was observed for condensin-depleted chromosomes (E = 50 ± 10 Pa) compared to wild-type chromosomes (E = 440 ± 50 Pa) (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Biggs, Hornick and Marko2018). These results agree with observations in vivo (Gerlich et al., Reference Gerlich, Hirota, Koch, Peters and Ellenberg2006; Houlard et al., Reference Houlard, Godwin, Metson, Lee, Hirano and Nasmyth2015) and the observation that SMC proteins are associated with stiffer chromosome regions (Almagro et al., Reference Almagro, Riveline, Hirano, Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2004). Depletion of condensin II impacts chromosome mechanics more than depletion of condensin I (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Biggs, Hornick and Marko2018). In contrast, when topoisomerase II was removed by incubation of the chromosomes in a high salt buffer, only a slight softening of the chromosomes was observed (Almagro et al., Reference Almagro, Riveline, Hirano, Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2004).

These results agree with the current structural model that condensin I and condensin II are involved in different levels of chromosome compaction: Condensin II serves as a major chromatin crosslinking element that forms the central axis of the chromosome and determines the stiffness of mitotic chromosomes, while condensin I drives longitudinal compaction by forming nested loops, compacting chromosomes without significantly increasing the elastic modulus (Gibcus et al., Reference Gibcus, Samejima, Goloborodko and Dekker2018; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Biggs, Hornick and Marko2018; Walther et al., Reference Walther, Hossain, Politi and Ellenberg2018). Meanwhile, topoisomerase II was found to be not essential for maintaining the elastic response of mitotic chromosomes (Almagro et al., Reference Almagro, Riveline, Hirano, Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov2004). Indeed, topoisomerase II can even relax stress applied on mitotic chromosomes by resolving double-stranded DNA entanglements in the presence of ATP (Kawamura et al., Reference Kawamura, Pope, Christensen and Marko2010). Therefore, these results are in agreement with a general structural model for condensation and segregation of mitotic chromosome: the condensins drive lengthwise compaction and chromosome stiffening by loop extrusion, converting chromosome entanglement into osmotic and mechanical stresses; release of those stresses by topoisomerase II then individualizes chromosomes and resolves sister chromatids. Notably, all results summarized in Table 1 agree with predictions from the current radial-loop model, although some of them were originally interpreted differently.

Correlation of mechanical characterization and imaging

Another approach to understanding the structural origin of chromosome mechanical properties combines imaging and mechanical characterization. Already in early studies, it was observed that chromosomes with a Giemsa-staining elongated inhomogeneously when stretched (Hliscs et al., Reference Hliscs, Mühlig and Claussen1997). A newer technique combines mechanical micromanipulation with fluorescence microscopy and microfluidics for quick buffer exchange (Fig. 6A). The power of this approach has been demonstrated recently by a combination of micromanipulation using micropipettes and immunofluorescence with anti-SMC2 antibodies (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Biggs, Hornick and Marko2018). SMC2 is one of the proteins of the condensin complex. This approach allowed relating the amount of condensin in the chromosome to its Young's modulus. It was found that the stiffness of the chromosome scales linearly with the amount of condensin, which again supports the notion that condensins are a main determinant of chromosome mechanics. Furthermore, the condensin staining pattern was observed to be discontinuous, suggesting that condensins organize mitotic chromosomes by forming isolated compaction centers that do not form a continuous scaffold (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Biggs, Hornick and Marko2018). This is in general agreement with the conclusions from the decondensation experiments (Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Monhait and Marko2002b). A feasible extension of this approach that combines labels for different SMC proteins might be a very powerful tool to elucidate the structure of the mitotic chromosome.

Fig. 6. Promising new approaches. (A) Combination of micromanipulation with fluorescence microscopy. The same chromosome is imaged before (a, b) and after (c, d) stretching, using both bright field (a, c) and fluorescence (b, d) microscopy with immunostaining against SMC2. (B) Polymer simulations of a minimal chromosome model consisting of two looped polymer strands (blue and red) held together by linkers (dark red) subjected to a pulling potential. Figures adapted from Sun et al. (Reference Sun, Biggs, Hornick and Marko2018). Reprinted by permission from Springer Nature: Chromosome Research, Copyright© 2018 Springer Nature and Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Isbaner and Heermann2013) under Creative Commons CC BY 3.0.

Robustness and emergence

In many of the chromosome modification examples discussed above, the qualitative mechanical response of the chromosomes was surprisingly little affected. This raises the question which physical principles are at the origin of the mechanical properties of mitotic chromosomes. Can the mechanical response be attributed to individual components or is it an emergent property arising from the interplay of different components (Zhou and Heald, Reference Zhou and Heald2020)? For other biopolymer networks, similar approaches have proven to be very fruitful for generating insight into the nature of their mechanical behavior. For example, our understanding of actomyosin networks comes in large parts from the combination of mechanical characterization and recent advancements in theoretical physics (Gardel et al., Reference Gardel, Valentine, Crocker, Bausch and Weitz2003; Lieleg et al., Reference Lieleg, Claessens, Luan and Bausch2008; Broedersz et al., Reference Broedersz, Depken, Yao, Pollak, Weitz and MacKintosh2010). Similarly, the experimental observation that DNA disentanglement by topoisomerase II and ATP softens mitotic chromosomes can be understood as changes of the chromatin topology that directly links to the stiffness of the chromosome using polymer physics models (Kawamura et al., Reference Kawamura, Pope, Christensen and Marko2010). Specifically, one example of how chromatin topology can influence the mechanical behavior was obtained in computer simulations of a simplified chromosome consisting only of a polymer fiber able to crosslink to itself (Fig. 6B) (Zhang and Heermann, Reference Zhang and Heermann2011; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Isbaner and Heermann2013; Goloborodko et al., Reference Goloborodko, Imakaev, Marko and Mirny2016a). These crosslinks led to the formation of loops in the chromatin fiber reminiscent of a mitotic chromosome. It was observed that the entropic repulsion between neighboring loops leads to straightening of the chromosome and effectively increases the bending rigidity (Zhang and Heermann, Reference Zhang and Heermann2011; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Isbaner and Heermann2013; Goloborodko et al., Reference Goloborodko, Imakaev, Marko and Mirny2016a). Another, experimental example of emergent mechanical properties came from the analysis of bending fluctuations of mitotic chromosomes clamped at one end. The fluctuations were found to be dominated by internal friction (Poirier and Marko, Reference Poirier and Marko2002a). Distinct from the usual result obtained when external hydrodynamic damping dominates, under the effect of ‘internal’ dissipation due to internal conformational rearrangements, the relaxation time of bending fluctuations of mitotic chromosomes was found to be independent of the wave-number (see above) (Poirier and Marko, Reference Poirier and Marko2002a). These examples illustrate that the mechanical properties of chromosomes are not merely the sum of the mechanical characteristics of their parts, but that properties emerging from the interplay of the parts play a crucial role as well.

Future challenges and emergent questions

In this contribution, we have reviewed studies of the mechanical properties of mitotic chromosomes and discussed how these can promote our understanding of chromosome condensation and disentanglement. Characteristic parameters such as Young's modulus, stretching modulus, and bending modulus measured by micropipette aspiration and micromanipulation techniques have provided important structural insights into the mitotic chromosome. As an important complementary data source, mechanical characterization can be combined with imaging and biochemical treatments to provide not only support for the radial-loop model of mitotic chromosomes, but also insights into the finer details of the heterogeneous chromosome structure, for example, the constitution of the axial scaffold. All those findings provide a general picture of the chromatin organization within mitotic chromosomes: Before compaction, the chromosome has a relatively loose organization of the chromatin fiber. The chromatin compaction is sequentially driven by condensin subunits by loop extrusion leading to the formation of the condensed mitotic chromosome, thereby converting chromosome entanglement into osmotic and mechanical stresses. Release of those stresses by topoisomerase II then drives the separation of sister chromatids.

Emergent questions are thus focused on the specifics of such kind of model: How does the relatively simple chromatin loop-extrusion mechanism drive the complex chromosome condensation procedure? Are there any other factors such as nucleosome interactions that also contribute to chromosome condensation? What is the detailed procedure for chromatin disentanglement? What is happening on the structural level during chromosome stretching? What are the load-bearing elements in the chromosome? How is the separation of sister chromatids controlled by the force applied through the mitotic spindle?

We foresee several future directions toward a better understanding of chromosome mechanics. Since the radius of the condensin scaffold is estimated to be below 300 nm (Gibcus et al., Reference Gibcus, Samejima, Goloborodko and Dekker2018; Walther et al., Reference Walther, Hossain, Politi and Ellenberg2018), some questions can be addressed by improving the spatial resolution of the instruments. For instance, compared to micropipettes, optical tweezers can provide better resolution and accuracy for force detection and extension (Heller et al., Reference Heller, Hoekstra, King, Peterman and Wuite2014). Advances in super-resolution fluorescence microscopy can help to better identify the dynamic distribution of proteins of interest such as condensins around the lateral and axial axis of mitotic chromosomes (Heller et al., Reference Heller, Sitters, Broekmans and Wuite2013; Birk Reference Birk2019). Another big opportunity lies in applying polymer models to elucidate the structure of chromosomes (Zhang and Heermann, Reference Zhang and Heermann2011; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Isbaner and Heermann2013). An approach that has proven to be very powerful is to use experimental data to restrict and inform polymer models of the chromosome. This strategy has been used, for example, to convert Hi-C contact maps into three-dimensional structural models (Gibcus et al., Reference Gibcus, Samejima, Goloborodko and Dekker2018), but a similar approach might also be suitable for high-resolution mechanical data.

Financial support

This work was financially supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (H.W., WI 5434/1-1), the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (E.J.G.P. and G.J.L.W., Physics Valorization Price), NovoNordisk (G.J.L.W.), and the European Research Council (G.J.L.W., MONOCHROME – DLV-883240).

Conflict of interest

None.