Introduction

Close observers of the diversity in the natural world generally appreciate why evolution has been likened not to the work of an engineer, but to that of a tinkerer (Jacob, Reference Jacob1977). By repurposing a genetic material under selective pressure, nature has evolved a myriad of ‘field-tested’ solutions to the challenges organisms face. Evolutionary tinkering is particularly evident in the microbial world, where selective pressure is high, effective population size is large, generation time is short, and genetic information can be exchanged widely and relatively quickly. As biologists delve ever deeper into the molecular and genetic mechanisms underlying the observed phenotypic diversity, we continue to learn more about fundamental biological processes and uncover new natural systems and phenomena. In addition to providing insight into the molecular underpinnings of life, some of these novel systems have been developed into various molecular technologies. For example, heat-stable polymerases discovered in thermophilic bacteria enabled the development of polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and restriction enzymes discovered by studying host responses to phages enabled recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) technologies.

One of the latest examples of how nature's solutions have been successfully adapted into a molecular technology is the development of clustered regularly interspaced short-palindromic repeat (CRISPR)-Cas (CRISPR-associated) systems for eukaryotic genome editing. CRISPR-Cas-mediated genome editing is a robust, easy-to-use method to precisely alter DNA sequences within the genome of living organisms. Because of the simplicity and efficiency of the system, it has been widely adopted and further developed, leading to an extraordinarily powerful molecular toolbox. Once microbiological curiosity, CRISPR has become a part of the common language of molecular biology, with its reach extending into nearly every corner of the life sciences and its impact going far beyond the confines of the laboratory. The story of CRISPR is one with two-intertwined aspects (Fig. 1): biological investigation to better understand these elegant systems and engineering of these systems into powerful molecular technologies. As the impact of these technologies spreads, it spurs further work into the biology, which continues to provide additional technological opportunities. Thus, the early part of the CRISPR revolution involved engineering Cas9 as genome editing technology, but through the recent discovery and development of additional Cas effectors, particularly the ribonucleic acid (RNA)-targeting Cas13 family, it has continued to expand into new areas. CRISPR-based technologies are being employed in diverse ways to improve human health and offer the potential to fundamentally change the way we treat disease.

Fig. 1. Two aspects of CRISPR: biology and technology. (a) CRISPR-Cas adaptive immune systems help microbes defend against phages and other foreign genetic materials. During the immunization phase (top), an adaptation module inserts a new spacer, a stretch of DNA derived from the genome of the invader, into the CRISPR array. During the defense phase (bottom), spacers are converted into guide RNAs that direct an interference module to matching target sequences, which are then cleaved. (b) CRISPR technologies have broad applications in the life sciences, medicine, and industrial biotechnology. The CRISPR molecular toolbox allows researchers to carry out precise genome and transcriptome editing in eukaryotic cells to advance our understanding of biology through the generation of useful animal and cellular models and interrogation of genetic variation, to boost biotechnology through engineering and production of novel materials and agricultural products, and to advance human health through detection of pathogens, development of novel therapeutic approaches, and elucidation of disease mechanisms. Image adapted from (Hsu et al., Reference Hsu, Lander and Zhang2014).

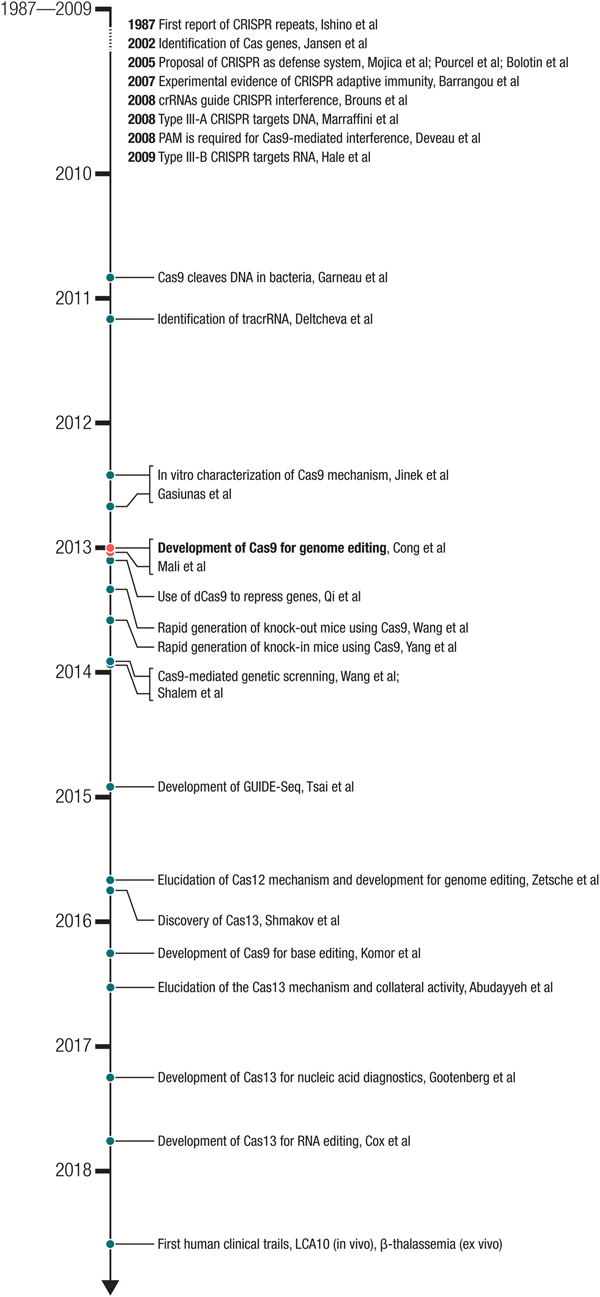

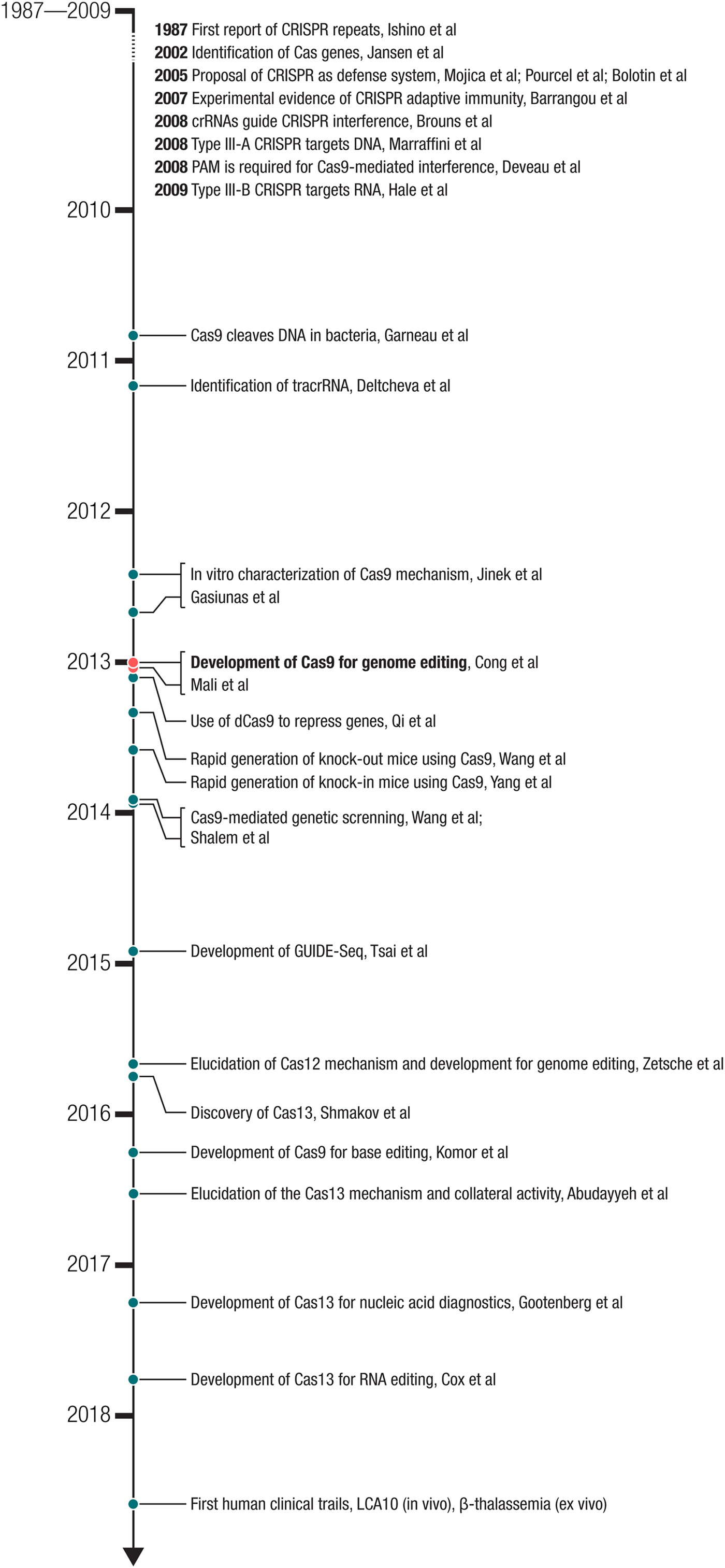

Here, I briefly overview the natural function of CRISPR-Cas systems, followed by a personal account and perspective of the time period over which CRISPR-Cas9 was developed for genome editing in eukaryotic cells. I also discuss the continuing study and remarkable biotechnological development of CRISPR-Cas systems beyond Cas9 (Fig. 2). In particular, I highlight some of the exciting applications of this technology and identify areas for future improvement. Although I have striven to include many primary studies, I apologize in advance to those whose work might have unintentionally been omitted. In addition to this perspective, there are a number of general reviews covering this topic (Doudna and Charpentier, Reference Doudna and Charpentier2014; Hsu et al., Reference Hsu, Lander and Zhang2014; van der Oost et al., Reference Van Der Oost, Westra, Jackson and Wiedenheft2014; Marraffini, Reference Marraffini2015; Sontheimer and Barrangou, Reference Sontheimer and Barrangou2015; Mojica and Rodriguez-Valera, Reference Mojica and Rodriguez-Valera2016; Barrangou and Horvath, Reference Barrangou and Horvath2017; Koonin and Makarova, Reference Koonin and Makarova2017; Lemay et al., Reference Lemay, Horvath and Moineau2017; Ishino et al., Reference Ishino, Krupovic and Forterre2018). I also refer readers to several reviews focused on various aspects related to CRISPR-Cas technologies, including the structure and mechanism of Cas effectors (Jackson and Wiedenheft, Reference Jackson and Wiedenheft2015; Garcia-Doval and Jinek, Reference Garcia-Doval and Jinek2017; Jiang and Doudna, Reference Jiang and Doudna2017), classification and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems (Koonin and Makarova, Reference Koonin and Makarova2017), and applications of the CRISPR technology in agriculture (Voytas and Gao, Reference Voytas and Gao2014; Gao, Reference Gao2018), animal and cellular modeling (Hotta and Yamanaka, Reference Hotta and Yamanaka2015), genetic screening (Shalem et al., Reference Shalem, Sanjana and Zhang2015; Doench, Reference Doench2017; Jost and Weissman, Reference Jost and Weissman2018), genome editing specificity (Tsai and Joung, Reference Tsai and Joung2016), base editing (Hess et al., Reference Hess, Tycko, Yao and Bassik2017; Rees and Liu, Reference Rees and Liu2018), drug discovery and development (Fellmann et al., Reference Fellmann, Gowen, Lin, Doudna and Corn2017), and therapeutic applications (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Platt and Zhang2015; Porteus, Reference Porteus2015; Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Chen, Lim, Zhao and Qi2016).

Fig. 2. Milestones in the development of CRISPR-based technologies. The development of Cas9 for genome editing ((Cong et al., Reference Cong, Ran, Cox, Lin, Barretto, Habib, Hsu, Wu, Jiang, Marraffini and Zhang2013) – submitted on October 5, 2012 and (Mali et al., Reference Mali, Yang, Esvelt, Aach, Guell, Dicarlo, Norville and Church2013b) – submitted on October 26, 2012) built on a number of important biological studies and spurred many powerful applications as well as the discovery of new CRISPR effectors such as the DNA-targeting Cas12 and RNA-targeting Cas13.

I would also like to take this opportunity to acknowledge all of the members of the CRISPR research community, who have contributed to elucidating the mechanism of CRISPR-Cas systems and developing and applying this extraordinary technology. It has been tremendously inspiring to see the multitude of ways that CRISPR-Cas systems continue to be applied. In addition, I am grateful to all of the collaborators and trainees with whom I have been fortunate to work alongside to uncover novel CRISPR biology and to develop and apply these remarkable technologies.

Biology of CRISPR-Cas-mediated adaptive immunity

Overview and nomenclature of CRISPR-Cas systems

CRISPR-Cas systems are adaptive immune systems found in roughly 50% of bacterial species and nearly all archaeal species sequenced to date (Makarova et al., Reference Makarova, Wolf, Alkhnbashi, Costa, Shah, Saunders, Barrangou, Brouns, Charpentier, Haft, Horvath, Moineau, Mojica, Terns, Terns, White, Yakunin, Garrett, Van Der Oost, Backofen and Koonin2015). These systems evolved over billions of years to defend microbes from the invasion of foreign nucleic acids such as bacteriophage genomes and conjugating plasmids by targeting their DNA or RNA. The molecular machinery involved in CRISPR-Cas immunity is encoded by the CRISPR locus as two sets of genetic components that are often located next to each other in microbial genomes: (1) an operon of multiple cas genes, and (2) a set of non-coding CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) including ones encoded by the signature repetitive CRISPR array consisting of spacers sandwiched between short-CRISPR repeats (Fig. 1a). Using these components, CRISPR-Cas systems mediate adaptive immunity (immunization and defense) through three general phases: adaptation, crRNA processing, and interference. First, during the adaptation phase, a subset of Cas proteins called the ‘adaptation module’ obtains and inserts fragments of an invading virus or other foreign genetic material as a ‘spacer’ sequence into the beginning of the CRISPR array in the host genome along with a newly duplicated CRISPR repeat. The sequence on the virus or plasmid matching the acquired spacer is called a protospacer. Second, the CRISPR array is transcribed and processed into individual crRNAs, each bearing an RNA fragment corresponding to the previously encountered virus or plasmid along with a portion of the CRISPR repeat. Third, during the interference phase, crRNAs guide the ‘interference module’, encoded either by complex comprising Cas effector subunits or by a single-effector protein, to destroy the invader.

There are many variations on the CRISPR theme, however, and the natural diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems is remarkably extensive, including systems that target DNA, systems that target RNA, and systems that target both DNA and RNA. CRISPR-Cas systems also operate in different ways, recognizing and cleaving their nucleic acid targets through distinct mechanisms mediated by various effector-crRNA complexes. Based on their unique effector proteins, CRISPR-Cas systems are currently classified into six types (I through VI), which are in turn grouped into two-broad classes (Makarova et al., Reference Makarova, Wolf, Alkhnbashi, Costa, Shah, Saunders, Barrangou, Brouns, Charpentier, Haft, Horvath, Moineau, Mojica, Terns, Terns, White, Yakunin, Garrett, Van Der Oost, Backofen and Koonin2015; Shmakov et al., Reference Shmakov, Smargon, Scott, Cox, Pyzocha, Yan, Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Makarova, Wolf, Severinov, Zhang and Koonin2017): class 1 systems (types I, III, and IV) use a multi-protein complex to achieve interference, and class 2 systems (types II, V, and VI) utilize a single-nuclease effector such as Cas9, Cas12, and Cas13 for interference.

Discovery and characterization of CRISPR-Cas systems

In 1987, a series of regularly-interspaced repeats of unknown function was observed in the genome of E. coli, documenting the first instance of a CRISPR array (Ishino et al., Reference Ishino, Shinagawa, Makino, Amemura and Nakata1987). In early 2002, clues to the function of CRISPR-Cas systems came from two-bioinformatics studies, one of which reported the presence of conserved operons that appeared to encode a novel DNA repair system, which we now know are cas genes (Makarova et al., Reference Makarova, Aravind, Grishin, Rogozin and Koonin2002), and the other of which reported the association between CRISPR arrays and cas genes (Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, Embden, Gaastra and Schouls2002). Next, it was observed that spacer sequences in between CRISPR repeats matched sequences in phage genomes, leading to the suggestion that CRISPR arrays could be involved in immunity against the corresponding phages (Mojica et al., Reference Mojica, Diez-Villasenor, Garcia-Martinez and Soria2005; Pourcel et al., Reference Pourcel, Salvignol and Vergnaud2005). Third, work focused on Streptococcus thermophilus similarly found that more spacers matched phage sequences and identified a large CRISPR-associated protein containing the DNA-cleaving HNH domain, which is now known as Cas9, the hallmark protein in type II systems (Bolotin et al., Reference Bolotin, Quinquis, Sorokin and Ehrlich2005). Despite the linkage between CRISPR-Cas and phage infection, the specific role that CRISPR spacers played in providing immunity remained unclear.

Experimental work with the type II system of S. thermophilus showed that the spacers in the CRISPR array are acquired from phages and specify immunity against specific phages carrying matching sequences. Moreover, cas genes are required for both immunization and phage interference (Barrangou et al., Reference Barrangou, Fremaux, Deveau, Richards, Boyaval, Moineau, Romero and Horvath2007). These exciting results established CRISPR-Cas as a microbial adaptive immune system. Insight into the molecular mechanism of CRISPR-Cas immunity came from work using a type I CRISPR-Cas system, which revealed that the CRISPR array is transcribed and processed into short crRNAs that provide recognition of the invading phages and that the effector module can be directed to multiple targets by changing the crRNA sequences (Brouns et al., Reference Brouns, Jore, Lundgren, Westra, Slijkhuis, Snijders, Dickman, Makarova, Koonin and Van Der Oost2008). Although the prevailing hypothesis at the time was that CRISPR-Cas systems achieved interference using an RNAi-like mechanism (Makarova et al., Reference Makarova, Grishin, Shabalina, Wolf and Koonin2006), there was evidence that the target was DNA, rather than RNA (Brouns et al., Reference Brouns, Jore, Lundgren, Westra, Slijkhuis, Snijders, Dickman, Makarova, Koonin and Van Der Oost2008). Another study reported that a type III-A CRISPR-Cas system limits horizontal gene transfer by targeting DNA (Marraffini and Sontheimer, Reference Marraffini and Sontheimer2008). However, other systems, such as the type III-B CRISPR-Cas system, target RNA instead (Hale et al., Reference Hale, Zhao, Olson, Duff, Graveley, Wells, Terns and Terns2009), highlighting the substantial mechanistic differences between CRISPR-Cas systems.

As the overall picture of CRISPR-Cas-mediated adaptive immunity began to take shape, studies also started to clarify the natural mechanism of type II CRISPR-Cas systems, which uses the nuclease effector Cas9. In one study, it was shown that a short well-conserved sequence motif at the end of CRISPR targets, called a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) (Mojica et al., Reference Mojica, Diez-Villasenor, Garcia-Martinez and Almendros2009), is required for Cas9-mediated interference (Deveau et al., Reference Deveau, Barrangou, Garneau, Labonte, Fremaux, Boyaval, Romero, Horvath and Moineau2008). In 2010, it was shown that S. thermophilus Cas9 is guided by crRNAs to create blunt double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA 3 bp upstream from the PAM at targeted sites in phage genomes and in plasmids and that Cas9 is the only protein required for DNA cleavage (Garneau et al., Reference Garneau, Dupuis, Villion, Romero, Barrangou, Boyaval, Fremaux, Horvath, Magadan and Moineau2010). In 2011, small-RNA sequencing of Streptococcus pyogenes revealed the presence of an additional small RNA associated with the CRISPR array. This additional RNA, termed tracrRNA, forms a duplex with direct repeat sequences on the pre-crRNA to produce mature crRNA, and it is required for Cas9-based interference (Deltcheva et al., Reference Deltcheva, Chylinski, Sharma, Gonzales, Chao, Pirzada, Eckert, Vogel and Charpentier2011). Another study in 2011 showed that the CRISPR-Cas locus from S. thermophilus could be expressed in E. coli, where it could mediate interference against plasmid DNA (Sapranauskas et al., Reference Sapranauskas, Gasiunas, Fremaux, Barrangou, Horvath and Siksnys2011). These studies collectively established that the nuclease complex of the natural Cas9 system contains three components (Cas9, crRNA, and tracrRNA) and that the DNA target site needs to be flanked by the appropriate PAM.

As the biology of CRISPR-Cas systems became better understood, it began to be adapted for use, first as an aid for bacterial strain typing (Pourcel et al., Reference Pourcel, Salvignol and Vergnaud2005; Horvath et al., Reference Horvath, Romero, Coute-Monvoisin, Richards, Deveau, Moineau, Boyaval, Fremaux and Barrangou2008, Reference Horvath, Coute-Monvoisin, Romero, Boyaval, Fremaux and Barrangou2009), and then in its native context by inoculating S. thermophilus with viruses to generate phage-resistant strains that can be deployed in industrial dairy applications, such as yogurt and cheese making (Quiberoni et al., Reference Quiberoni, Moineau, Rousseau, Reinheimer and Ackermann2010). Additional suggestions for its application were also raised, including microbial gene silencing (Sorek et al., Reference Sorek, Kunin and Hugenholtz2008), combating antibiotic resistance, and targeted DNA destruction (Marraffini and Sontheimer, Reference Marraffini and Sontheimer2008; Garneau et al., Reference Garneau, Dupuis, Villion, Romero, Barrangou, Boyaval, Fremaux, Horvath, Magadan and Moineau2010).

Development of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome editing

The ability to make precise changes to the genome holds great promise for advancing our understanding of biology and human health as well as providing new approaches to treating grievous diseases. The demonstration in 1987, the same year that CRISPR was first reported, of targeted gene insertion via homologous recombination in mice was a major breakthrough (Doetschman et al., Reference Doetschman, Gregg, Maeda, Hooper, Melton, Thompson and Smithies1987; Thomas and Capecchi, Reference Thomas and Capecchi1987), but the efficiency in mammalian cells was extremely low outside of mouse embryonic stem cells. Work in both yeast and mammalian cells demonstrated that the efficiency of gene insertion could be increased through the generation of a DSB at the target site (Rudin et al., Reference Rudin, Sugarman and Haber1989; Plessis et al., Reference Plessis, Perrin, Haber and Dujon1992; Rouet et al., Reference Rouet, Smih and Jasin1994). These observations motivated the development of targetable nucleases such as meganucleases, zinc finger nucleases, and transcription activator-like effector (TALE) nucleases that can be customized to recognize specific DNA sequences and generate DSBs at specific loci to facilitate genome editing (reviewed in (Urnov et al., Reference Urnov, Rebar, Holmes, Zhang and Gregory2010; Joung and Sander, Reference Joung and Sander2013; Kim and Kim, Reference Kim and Kim2014)). However, the targeting capacity of each of these technologies was limited, and it was challenging to reprogram them in practice, ultimately dampening their impact.

As a Junior Fellow at Harvard in 2009, I had experienced firsthand the challenges of working with zinc finger nucleases. After reading studies describing the DNA recognition mechanism of microbial TALE proteins (Boch et al., Reference Boch, Scholze, Schornack, Landgraf, Hahn, Kay, Lahaye, Nickstadt and Bonas2009; Moscou and Bogdanove, Reference Moscou and Bogdanove2009), I asked Le Cong, a rotation graduate student, to join me to develop TALEs for use in mammalian cells (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Cong, Lodato, Kosuri, Church and Arlotta2011). In 2010, I accepted a faculty position at MIT and the Broad Institute, planning to build a research program around genome and transcriptome editing. I started to set up my lab in January 2011, and Cong joined as my first graduate student. The very next month, I heard Michael Gilmore speak at the Broad Institute about his studies on Enterococcus bacteria, during which he mentioned that Enterococcus carried CRISPR-Cas systems, which contained a new class of nucleases. Given my interest in genome editing, I was intrigued by the prospect of a new class of nucleases. After studying the CRISPR-Cas literature, I immediately recognized that CRISPR-Cas would be easier to reprogram than TALEs, and I decided to refocus a significant portion of my genome editing efforts on adapting Cas9 for genome editing in eukaryotic cells.

In early 2011, it was already known that Cas9 could cleave DNA in bacterial cells when directed by a crRNA (Garneau et al., Reference Garneau, Dupuis, Villion, Romero, Barrangou, Boyaval, Fremaux, Horvath, Magadan and Moineau2010). Based on the literature, it was also known that the nuclease complex of the natural Cas9 system contains three components (Cas9, crRNA, and tracrRNA). However, CRISPR-Cas systems had only been studied in bacterial and biochemical systems, and they had not been explored in the context of eukaryotic cells. Thus, the key question that needed to be answered, in my mind, was whether Cas9 could be engineered to achieve genome editing in eukaryotic cells. Bacterial enzymes evolved to function optimally in their native bacterial environment, which has substantially different biochemical properties than that of the intracellular environment of a eukaryotic cell. Indeed, I knew that previous attempts to harness bacterial systems for use in eukaryotic cells had failed, including Group II introns (Mastroianni et al., Reference Mastroianni, Watanabe, White, Zhuang, Vernon, Matsuura, Wallingford and Lambowitz2008) and ribozymes (Link and Breaker, Reference Link and Breaker2009). From my past experiences developing microbial opsins for use in mammalian neurons for optogenetics (Boyden et al., Reference Boyden, Zhang, Bamberg, Nagel and Deisseroth2005; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wang, Brauner, Liewald, Kay, Watzke, Wood, Bamberg, Nagel, Gottschalk and Deisseroth2007) and TALEs for use in mammalian cells for genome editing (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Cong, Lodato, Kosuri, Church and Arlotta2011), I decided to directly answer the question of whether Cas9 could be used as a programmable nuclease in eukaryotic cells by using a human cell culture system. Working with human cells, I developed a three-component CRISPR-Cas9 system – Cas9, crRNA, and tracrRNA – for genome editing.

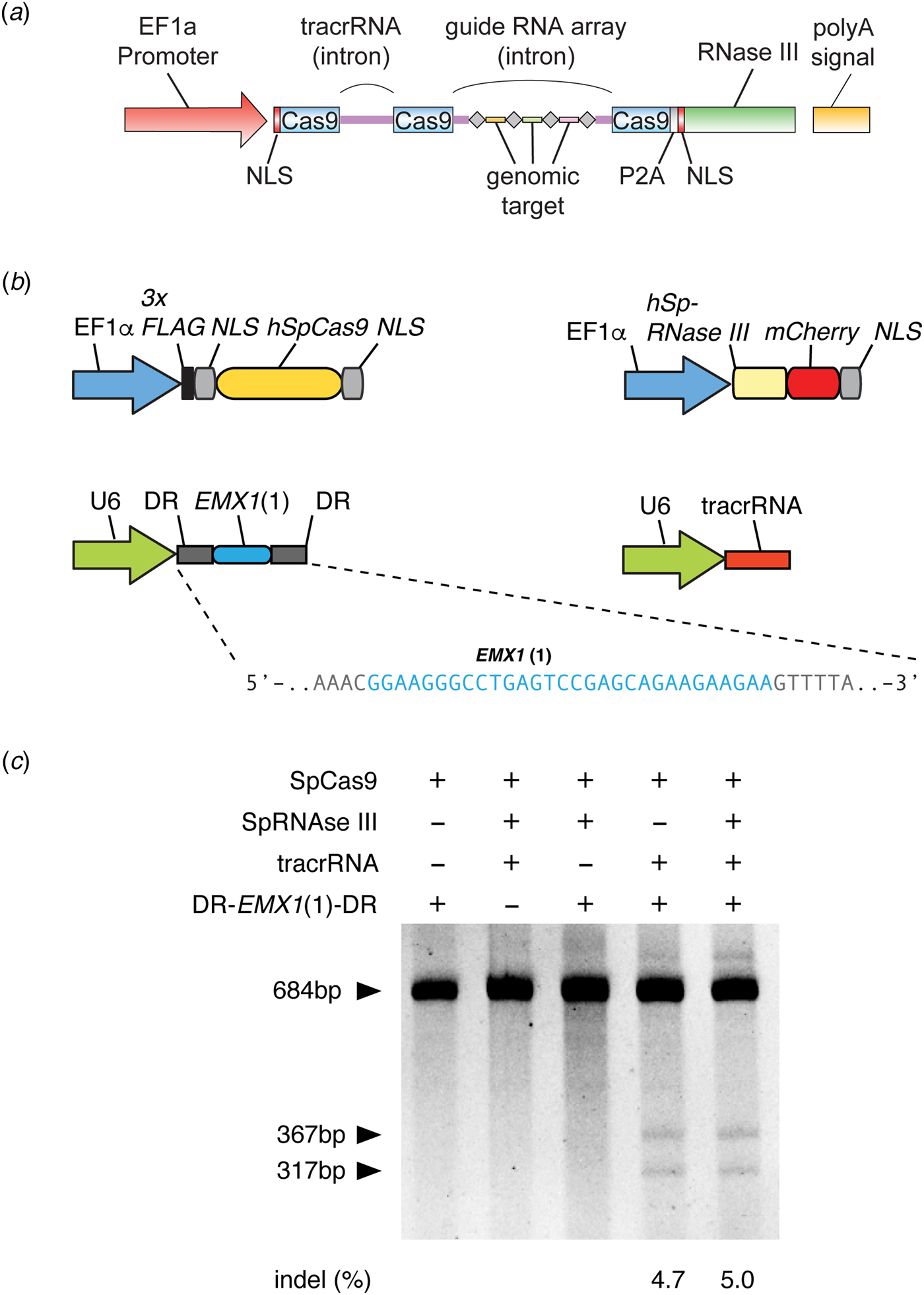

As a brand new Assistant Professor, I not only designed but also carried out experiments in the laboratory myself, while mentoring trainees, recruiting lab members, and applying for grants. In one of the grants submitted to the National Institutes of Health in January 2012, I described my strategy to use a three-component Cas9 system (Cas9, crRNA, and tracrRNA) for genome editing in mammalian cells, as was later published in our study (Fig. 3) (Cong et al., Reference Cong, Ran, Cox, Lin, Barretto, Habib, Hsu, Wu, Jiang, Marraffini and Zhang2013). The strategy for this work was based on the synthesis of the available literature in the CRISPR field, which had established the requirement for these three components for function in bacteria.

Fig. 3. Development of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome editing. (a) The design of a three-component system (Cas9, crRNA, and tracrRNA) for Cas9-mediated genome editing in eukaryotic cells, which was included in a grant submitted in January 2012 to the National Institutes of Health. In this design, the EF1a promoter drives expression of Cas9 (with a NLS) and the tracrRNA and guide RNA array with four genomic targets. In addition, RNase III is expressed to aid the processing of crRNA, although we later determined it is not necessary (see panel c). Image adapted from NIH Grant 5R01DK097768. (b) Design of the three-component system used in human cells to demonstrate editing of the human genome. S. pyogenes Cas9, CRISPR array (DR-EMX(1)-DR), and tracrRNA are individually expressed. The guide sequence in the CRISPR array targets the human EMX1 gene. Image adapted from Cong et al. (Reference Cong, Ran, Cox, Lin, Barretto, Habib, Hsu, Wu, Jiang, Marraffini and Zhang2013). (c) Polyacrylamide gel showing successful editing of the EMX1 target in the human genome. The SURVEYOR reaction is used to detect the presence of Cas9-induced indels at the EMX1 locus. Transfection of Cas9, CRISPR array, and tracrRNA alone mediated successful genome editing (RNase III is not required). Image adapted from Cong et al. (Reference Cong, Ran, Cox, Lin, Barretto, Habib, Hsu, Wu, Jiang, Marraffini and Zhang2013).

During the course of our experiments, a detailed biochemical analysis of the mechanism of Cas9 in vitro was published (Jinek et al., Reference Jinek, Chylinski, Fonfara, Hauer, Doudna and Charpentier2012). First, it showed that the purified S. pyogenes Cas9-crRNA-tracrRNA complex cleaves DNA 3 bp upstream of the PAM of the target site, in agreement with previous in vivo results with the S. thermophilus system (Garneau et al., Reference Garneau, Dupuis, Villion, Romero, Barrangou, Boyaval, Fremaux, Horvath, Magadan and Moineau2010). Second, it showed that tracrRNA and crRNA are both required for target cleavage by the Cas9-crRNA-tracrRNA complex. Furthermore, by truncating the tracrRNA, the study found that a short fragment of the tracrRNA (nucleotides 23 to 48, without the 3′ stem loops) was sufficient for supporting robust dual-RNA-guided cleavage of DNA by the Cas9-crRNA-tracrRNA complex in vitro. Third, it showed that the HNH domain is responsible for cleaving the target DNA strand and the RuvC domain cleaves the non-target DNA strand. Inactivation of either domain turns the Cas9-crRNA-tracrRNA complex into a DNA nickase. Fourth, it showed that single-base mutations in the PAM and in the 3′ region of the guide sequence abolished DNA cleavage by the Cas9-crRNA-tracrRNA complex, whereas single-base mismatches closer to the 5′ region of the guide RNA did not. Fifth, it showed that the crRNA and the 23-48-nt tracrRNA can be fused into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) and this Cas9-sgRNA two-component system can mediate cleavage of plasmid DNA under biochemical conditions.

Three months later, a biochemical analysis, using a purified complex containing the S. thermophilus Cas9 and crRNA, reported similar findings (Gasiunas et al., Reference Gasiunas, Barrangou, Horvath and Siksnys2012). First, the study showed that the Cas9-crRNA complex cleaves target DNA 3 bp upstream of the PAM of the target site, also in agreement with previous in vivo results with the S. thermophilus system (Garneau et al., Reference Garneau, Dupuis, Villion, Romero, Barrangou, Boyaval, Fremaux, Horvath, Magadan and Moineau2010). Second, it showed that the Cas9-crRNA complex binds to dsDNA containing both the binding site as well as PAM. Third, the study showed that the HNH domain cleaves the target DNA strand and the RuvC domain cleaves the non-target strand. Inactivation of either domain turned the Cas9-crRNA complex into a DNA nickase. However, this study purified the Cas9-crRNA complex from bacteria without analyzing the components of the complex. As a result, the paper provided an incomplete picture of the Cas9 molecular mechanism for in vitro cleavage and failed to identify the requirement for tracrRNA for Cas9 function.

While the in vitro two-component system highlighted the potential of exploiting Cas9 for genome editing, as this work was conducted entirely in vitro, it did not identify the critical components for achieving robust genome editing in cells and did not demonstrate that Cas9 could be used for genome editing. Thus, although the biochemical demonstration of RNA-guided DNA cleavage is often equated with Cas9-mediated genome editing, even within the scientific community there were concerns as to whether Cas9 could be made to function in eukaryotic cells (Carroll, Reference Carroll2012).

At the time, we had already established that Cas9 could function in human cells. Working alongside my first trainees, including Le Cong and Ann Ran, who are co-first authors of our publication (Cong et al., Reference Cong, Ran, Cox, Lin, Barretto, Habib, Hsu, Wu, Jiang, Marraffini and Zhang2013), we focused on two orthologs of Cas9 that had been previously studied using bacterial genetics and had complementary advantages: S. thermophilus Cas9 (StCas9), which was small enough to be packaged into an adeno-associated viral vector (AAV) for in vivo delivery, and S. pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), which had a less restrictive PAM sequence (SpCas9, PAM 5′-NGG, can target on average every 12·7 bp in the human genome, whereas StCas9, PAM 5′-NNAGAAW, can target on average every 106·6 bp in the human genome), and thus broader targeting potential. First, we found that both SpCas9 and StCas9 can be engineered to mediate genome editing in human and mouse cells. However, Cas9 aggregated in the nucleolus, pointing to the obstacle of correct subcellular localization when moving a bacterial system into eukaryotic cells. After experimenting with a number of nuclear localization signals (NLSs), we found that the combination of a monopartite and a bipartite NLS allowed Cas9 to localize efficiently into the human cell nucleus without any aggregation in the nucleolus. Second, we found that although the natural bacteria expressed multiple isoforms of the tracrRNA, all of which can provide CRISPR immunity in bacteria (Deltcheva et al., Reference Deltcheva, Chylinski, Sharma, Gonzales, Chao, Pirzada, Eckert, Vogel and Charpentier2011), only the 89-nt isoform was stably expressed in human cells and was important for achieving robust genome editing. Third, we found that across 16 target sites in human and mouse cells, the three-component system for SpCas9 and StCas9 can mediate robust editing of the genome. Fourth, we found that a CRISPR array encoding multiple spacers can be processed by human cells into individual guide RNAs to target multiple genes in the genome. Fifth, we showed that DSBs introduced by Cas9 can stimulate homologous recombination, leading to targeted gene insertion, and that Cas9 nickase activity can also stimulate homologous recombination in cells, while avoiding the formation of DSB-induced indels. Sixth, we also explored a two-component design. We found that the additional 3′ stem loops on the tracrRNA are important for gene editing, as the three-component system achieved significantly more robust genome editing in human cells than the two-component design employed, which failed to edit at a number of genomic sites. Together, these results established a foundation for the molecular mechanism by which CRISPR-Cas9 can mediate robust genome editing and further underscores that the ability of CRISPR-Cas9 to function in eukaryotic cells cannot be predicted from in vitro studies (Cong et al., Reference Cong, Ran, Cox, Lin, Barretto, Habib, Hsu, Wu, Jiang, Marraffini and Zhang2013).

If Cas9 could function in eukaryotic cells, however, it would unlock the potential for a range of sought after applications in research, biotechnology, and medicine. It was therefore not surprising that, in addition to our efforts to develop Cas9 for genome editing, other groups were inspired by the biochemical characterization of Cas9 (Jinek et al., Reference Jinek, Chylinski, Fonfara, Hauer, Doudna and Charpentier2012) to explore applications of Cas9 as well. Concurrent with our study, a second report of gene editing using Cas9 was published (Mali et al., Reference Mali, Yang, Esvelt, Aach, Guell, Dicarlo, Norville and Church2013b). Shortly thereafter, additional studies also reported the use of Cas9 in human and animal cells (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Kim, Kim and Kim2013; Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Fu, Reyon, Maeder, Tsai, Sander, Peterson, Yeh and Joung2013; Jinek et al., Reference Jinek, East, Cheng, Lin, Ma and Doudna2013) and the use of a catalytically inactivated variant of Cas9 to achieve targeted gene repression (Qi et al., Reference Qi, Larson, Gilbert, Doudna, Weissman, Arkin and Lim2013).

Initial impact of Cas9-mediated genome editing

Following the demonstration of Cas9-mediated genome editing in eukaryotic cells, many outstanding scientists contributed to the advancement and application of the technology, pushing the field ahead at a remarkable rate. We continued to develop the technology by focusing on three major areas: (1) further understanding the biology of Cas9 so as to improve and extend its utility; (2) developing applications of Cas9, including genome-wide screening, a Cas9 knock-in mouse, and conversion of Cas9 to a catalytically inactive programmable DNA-binding scaffold; and (3) exploring the natural diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems to identify other Cas effectors with unique properties that may be advantageous for technological development. Through these endeavors we had the opportunity to collaborate with a number of talented researchers from diverse backgrounds, further amplifying the impact of CRISPR-based technologies.

One way the immediate impact of Cas9 can be seen is in its rapid adoption for other organisms, which highlights the broad utility of this tool as well as the robustness and ease-of-use of the system. Catalyzed by the success of Cas9-mediated genome editing in human cells, within a year, groups from around the world reported the successful application of Cas9 in a number of eukaryotic model organisms, including yeast (DiCarlo et al., Reference Dicarlo, Norville, Mali, Rios, Aach and Church2013), mice (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Yang, Shivalila, Dawlaty, Cheng, Zhang and Jaenisch2013), Drosophila (Gratz et al., Reference Gratz, Cummings, Nguyen, Hamm, Donohue, Harrison, Wildonger and O'connor-Giles2013), C. elegans (Friedland et al., Reference Friedland, Tzur, Esvelt, Colaiácovo, Church and Calarco2013), Arabidopsis (Li et al., Reference Li, Norville, Aach, Mccormack, Zhang, Bush, Church and Sheen2013), Xenopus (Nakayama et al., Reference Nakayama, Fish, Fisher, Oomen-Hajagos, Thomsen and Grainger2013), and non-human primates (Niu et al., Reference Niu, Shen, Cui, Chen, Wang, Wang, Kang, Zhao, Si, Li, Xiang, Zhou, Guo, Bi, Si, Hu, Dong, Wang, Zhou, Li, Tan, Pu, Wang, Ji, Zhou, Huang, Ji and Sha2014). Cas9 was also successfully deployed in a number of agriculturally important species in that first year, such as rice and wheat (Shan et al., Reference Shan, Wang, Li, Zhang, Chen, Liang, Zhang, Liu, Xi, Qiu and Gao2013), sorghum (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Zhou, Bi, Fromm, Yang and Weeks2013), and maize (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Zhang, Chen and Gao2014). Before the year's end, the first reports were published on the use of Cas9 to correct a cataract-causing mutation in a mouse, leading to reversal of the disease phenotype (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Liang, Wang, Bai, Tang, Bao, Yan, Li and Li2013). In parallel, a number of improvements and extensions of the technology were reported in quick succession.

The impact of the CRISPR-based technologies is due in no small part to the open sharing culture of the CRISPR field, which has enabled applications and further development of CRISPR-based technologies to flourish. This has been facilitated through on-line resources, such as the creation of numerous web-based tools for guide design (Hsu et al., Reference Hsu, Scott, Weinstein, Ran, Konermann, Agarwala, Li, Fine, Wu, Shalem, Cradick, Marraffini, Bao and Zhang2013; Bae et al., Reference Bae, Park and Kim2014; Schmid-Burgk et al., Reference Schmid-Burgk, Schmidt, Gaidt, Pelka, Latz, Ebert and Hornung2014; Labun et al., Reference Labun, Montague, Gagnon, Thyme and Valen2016; Pinello et al., Reference Pinello, Canver, Hoban, Orkin, Kohn, Bauer and Yuan2016; Concordet and Haeussler, Reference Concordet and Haeussler2018; Listgarten et al., Reference Listgarten, Weinstein, Kleinstiver, Sousa, Joung, Crawford, Gao, Hoang, Elibol, Doench and Fusi2018), and through the annual CRISPR meetings. CRISPR reagents have also been shared widely and openly. To date, more than 350 laboratories from around the world have made their CRISPR-based reagents accessible through the non-profit molecular reagent sharing organization Addgene. For my own group, we have made it a priority to help researchers benefit from the CRISPR technological advances we made by disseminating reagents as well as know-how for CRISPR-based technologies. Through a combination of direct mailing as well as distribution through Addgene, we have been able to share more than 52 000 CRISPR reagents to researchers at more than 2300 institutions spanning 62 countries.

From Cas9 to beyond: Cas12 and Cas13

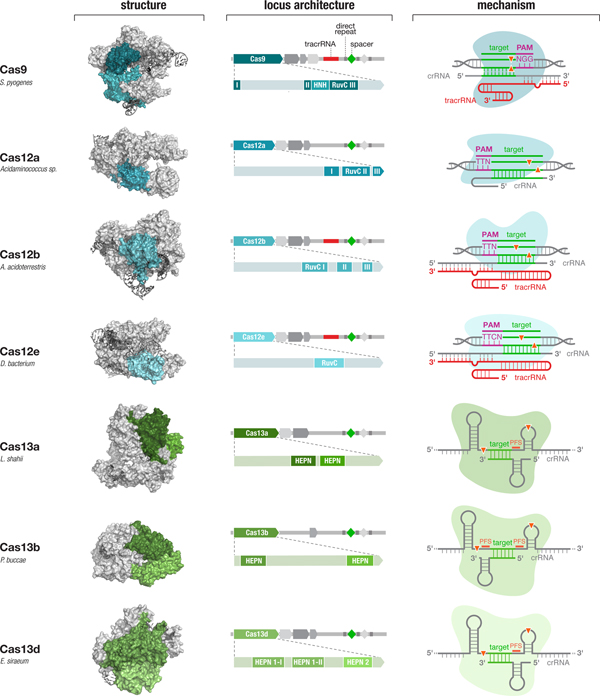

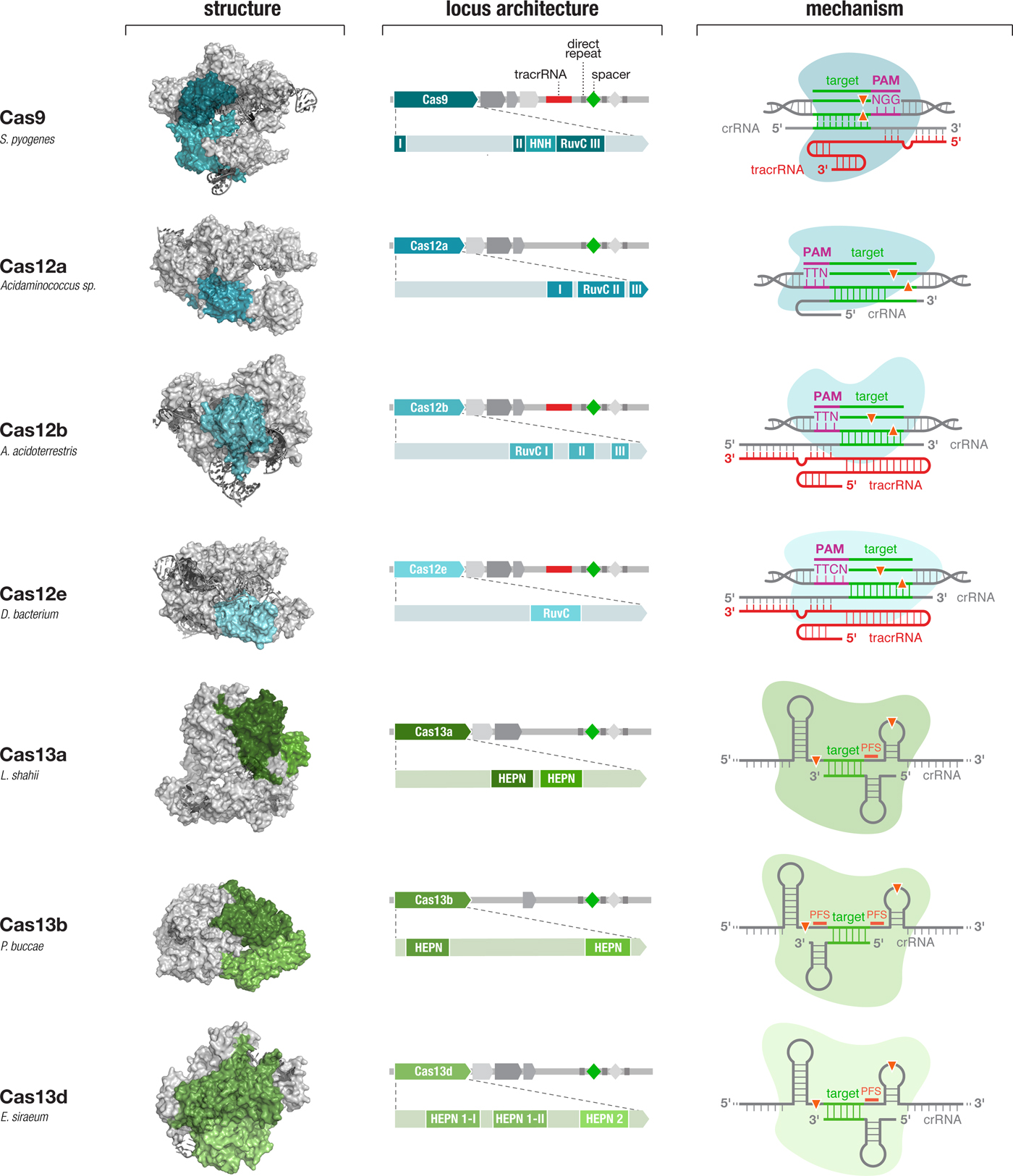

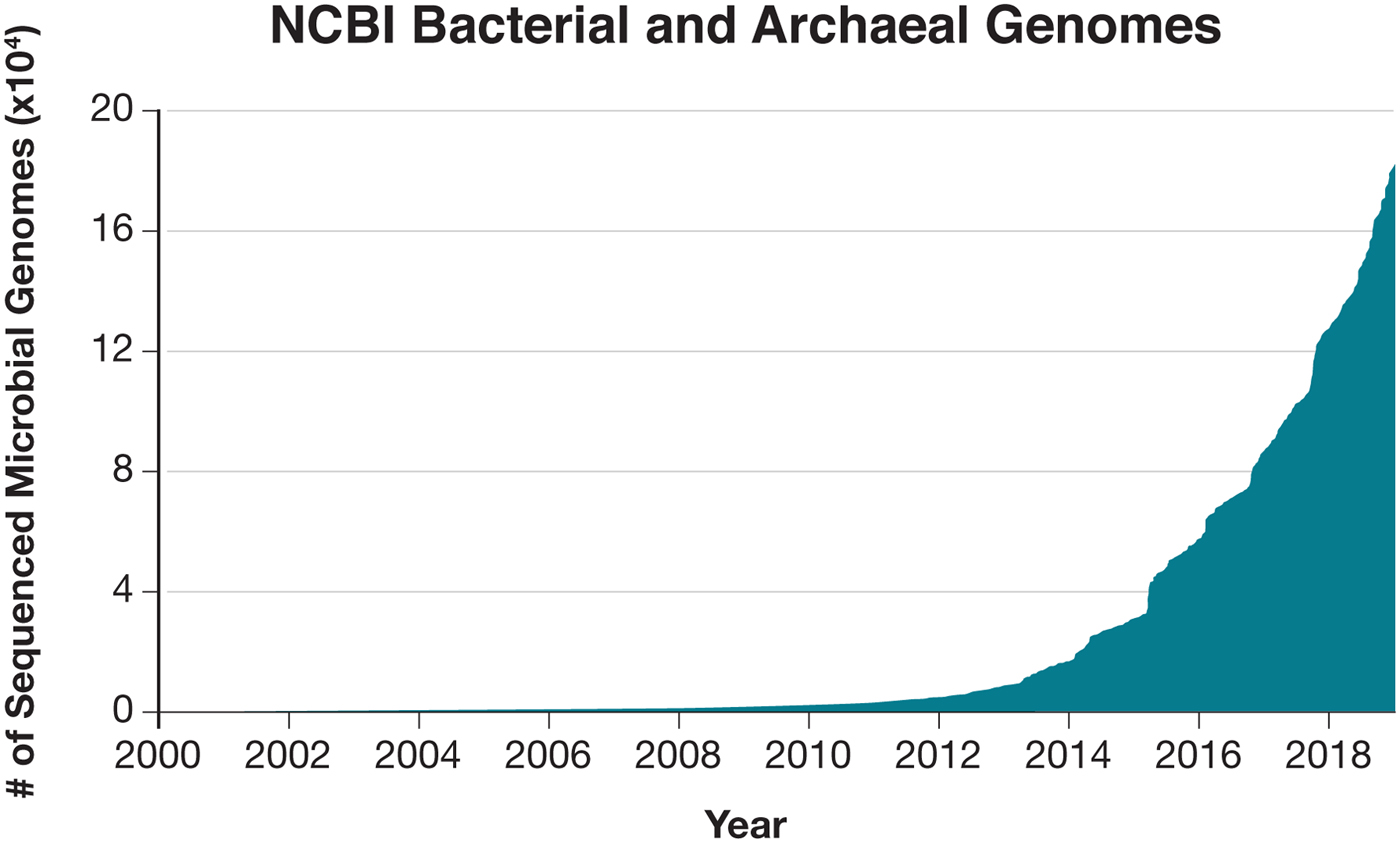

The development of other molecular technologies, such as restriction enzymes (Loenen et al., Reference Loenen, Dryden, Raleigh, Wilson and Murray2014) and green fluorescent proteins (Rodriguez et al., Reference Rodriguez, Campbell, Lin, Lin, Miyawaki, Palmer, Shu, Zhang and Tsien2017), has benefitted significantly from explorations of natural diversity. Similarly, my own experience with the development of optogenetics has taught me the power of exploring the diversity of microbial opsins. Therefore, we turned to the natural diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems to identify other Cas effectors with the potential to expand the capabilities of CRISPR-based technologies. By mining the microbial diversity for signatures of CRISPR-Cas systems (e.g., conserved genes and CRISPR-like repeat sequences), we discovered and elucidated the functions of two new types of CRISPR-Cas systems and developed them to significantly expand the CRISPR toolbox (Shmakov et al., Reference Shmakov, Abudayyeh, Makarova, Wolf, Gootenberg, Semenova, Minakhin, Joung, Konermann, Severinov, Zhang and Koonin2015, Reference Shmakov, Smargon, Scott, Cox, Pyzocha, Yan, Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Makarova, Wolf, Severinov, Zhang and Koonin2017; Zetsche et al., Reference Zetsche, Gootenberg, Abudayyeh, Slaymaker, Makarova, Essletzbichler, Volz, Joung, Van Der Oost, Regev, Koonin and Zhang2015a; Smargon et al., Reference Smargon, Cox, Pyzocha, Zheng, Slaymaker, Gootenberg, Abudayyeh, Essletzbichler, Shmakov, Makarova, Koonin and Zhang2017) (Fig. 4). These discoveries prompted other investigations of microbial diversity, revealing additional subtypes of CRISPR-Cas systems (Burstein et al., Reference Burstein, Harrington, Strutt, Probst, Anantharaman, Thomas, Doudna and Banfield2017; Harrington et al., Reference Harrington, Burstein, Chen, Paez-Espino, Ma, Witte, Cofsky, Kyrpides, Banfield and Doudna2018; Konermann et al., Reference Konermann, Lotfy, Brideau, Oki, Shokhirev and Hsu2018; Shmakov et al., Reference Shmakov, Makarova, Wolf, Severinov and Koonin2018; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Chong, Zhang, Makarova, Koonin, Cheng and Scott2018b) and providing insight into the origin, evolution, and function of these elegant systems.

Fig. 4. Diverse class 2 CRISPR effectors have unique molecular features that contribute to an expansive toolbox for genome and transcriptome editing. To date, effectors from seven sub-types of CRISPR-Cas system have been developed for molecular technologies. These effectors differ in their locus architecture, structure, and mechanism, creating many opportunities for engineering CRISPR-based technologies. The locus architecture shows the CRISPR array, tracrRNA (if present), and catalytic domains of the effector protein. The crystal structures for each effector are shown with the catalytic domains colored as in the locus architecture. The mechanism of each effector depicts how it binds its DNA or RNA target, as well as the configuration of the crRNA and tracrRNA (if present). Crystal structures were obtained from the PDB (S. pyogenes Cas9, PDB ID: 4OO8; Acidaminococcus sp. Cas12a, 5B43; Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris Cas12b, 5U30; Deltaproteobacteria bacterium Cas12e, 6NY1; Leptotrichia shahii Cas13a, 5WTK; Prevotella buccae Cas13b, 6DTD; Eubacterium siraeum Cas13d, 6E9E).

SaCas9

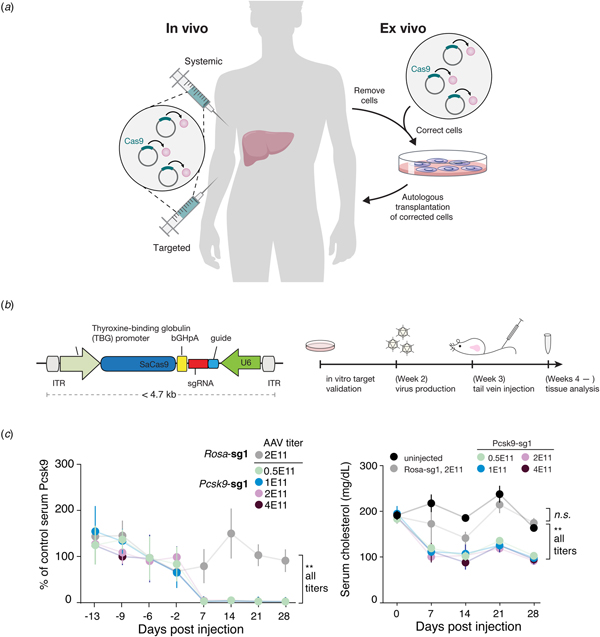

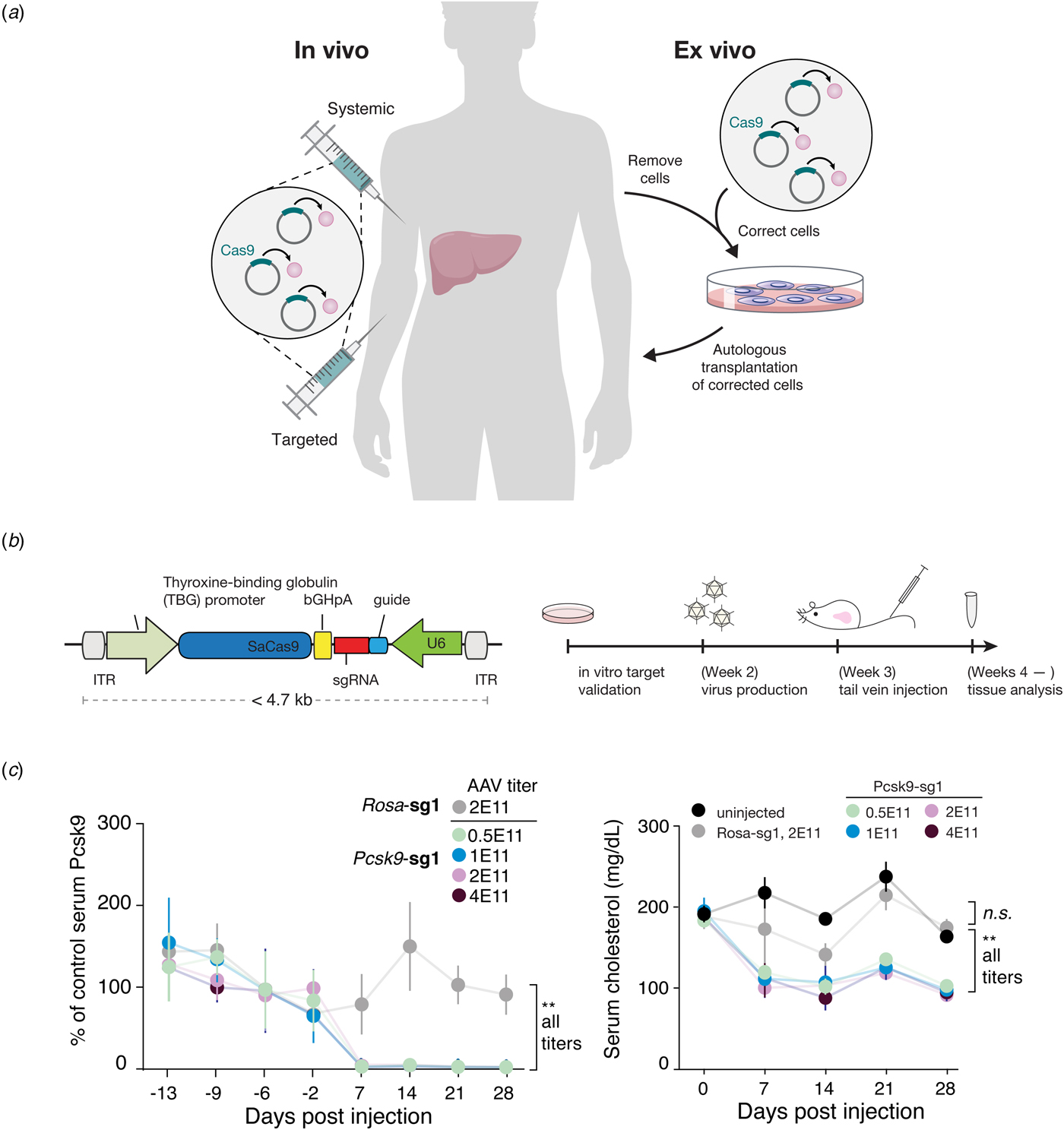

Beyond its immediate utility in the lab, there was enormous interest in using Cas9-mediated genome editing as a therapeutic that could theoretically treat thousands of genetic diseases. One limitation to the therapeutic use of SpCas9, however, was its relatively large size, which made delivering it challenging. We therefore sought to identify smaller Cas9 orthologs that worked efficiently in mammalian cells while maintaining a broad targeting range. We characterized a number of CRISPR-Cas9 systems and profiled their mammalian genome editing activity. One Cas9 ortholog from Staphylococcus aureus (SaCas9, PAM 5′-NNGRRT) showed the highest levels of activity in human cells (Ran et al., Reference Ran, Cong, Yan, Scott, Gootenberg, Kriz, Zetsche, Shalem, Wu, Makarova, Koonin, Sharp and Zhang2015). SaCas9 is more than 1 kb shorter than SpCas9, which allowed us to deliver it, along with a guide RNA, on a single-AAV vector for in vivo use (Ran et al., Reference Ran, Cong, Yan, Scott, Gootenberg, Kriz, Zetsche, Shalem, Wu, Makarova, Koonin, Sharp and Zhang2015). SaCas9 is now being developed as the first in vivo genome editing medicine for humans (see below) (Allergan, 2019). SpCas9 is also being advanced for therapeutic applications. However, due to its large size, clinical trials employing SpCas9 are focused on electroporation of patient cells ex vivo (Vertex, 2018a, 2018b).

Cas12

We next went beyond Cas9 orthologs to study other CRISPR-Cas systems, beginning with a putative new type of class 2 CRISPR-Cas system, type V, characterized by the Cas12 family of effector proteins. The first Cas12 enzyme, classified as type V-A and referred to as Cas12a (previously known as Cpf1) was identified in the genomes of Prevotella and Francisella and contained a large protein of unknown function (Schunder et al., Reference Schunder, Rydzewski, Grunow and Heuner2013; Vestergaard et al., Reference Vestergaard, Garrett and Shah2014; Makarova et al., Reference Makarova, Wolf, Alkhnbashi, Costa, Shah, Saunders, Barrangou, Brouns, Charpentier, Haft, Horvath, Moineau, Mojica, Terns, Terns, White, Yakunin, Garrett, Van Der Oost, Backofen and Koonin2015). Cas12a is a distinct enzyme unrelated to Cas9. A number of Francisella species contain Cas12a in association with putative CRISPR arrays, including F. novicida. Heterologous expression of the F. novicida CRISPR-Cas12a locus in E. coli led to interference of plasmid DNA transformation, establishing CRISPR-Cas12a as a bona fide CRISPR-Cas system and revealing that Cas12a requires a T-rich PAM sequence preceding the DNA target site (Zetsche et al., Reference Zetsche, Gootenberg, Abudayyeh, Slaymaker, Makarova, Essletzbichler, Volz, Joung, Van Der Oost, Regev, Koonin and Zhang2015a). In contrast to Cas9, the Cas12a system does not contain a tracrRNA, and its DNA cleavage results in a 5′ overhang instead of a blunt DSB (Zetsche et al., Reference Zetsche, Gootenberg, Abudayyeh, Slaymaker, Makarova, Essletzbichler, Volz, Joung, Van Der Oost, Regev, Koonin and Zhang2015a). Also, unlike Cas9, which utilizes host RNase III to process its CRISPR array, Cas12a itself has RNase activity and processes its own pre-crRNA array into individual crRNAs (Fonfara et al., Reference Fonfara, Richter, Bratovič, Le Rhun and Charpentier2016).

A search for Cas12a orthologs identified two-Cas12a enzymes, from Acidaminococcus and Lachnospiraceae, with strong cleavage activity in human cells, comparable to SpCas9 (Zetsche et al., Reference Zetsche, Gootenberg, Abudayyeh, Slaymaker, Makarova, Essletzbichler, Volz, Joung, Van Der Oost, Regev, Koonin and Zhang2015a). Apart from expanding the range of genomic targets that can be edited given that it has a different PAM than Cas9, Cas12a-mediated editing has several advantages over Cas9: it is significantly more specific (Kleinstiver et al., Reference Kleinstiver, Tsai, Prew, Nguyen, Welch, Lopez, Mccaw, Aryee and Joung2016b; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kim, Ryu, Kang, Kim and Kim2017b), which is important for therapeutic applications; it offers a simplified guide design because it does not require tracrRNA; it generates over-hanging ends, rather than the blunt ends created by Cas9, which may be beneficial for the introduction of new sequences (Moreno-Mateos et al., Reference Moreno-Mateos, Fernandez, Rouet, Vejnar, Lane, Mis, Khokha, Doudna and Giraldez2017); it has smaller molecular size which is more suitable for viral packaging, and it is ideally suited for multiplex genome editing because multiple guide RNAs can be easily expressed as a single transcript and subsequently processed into individual guide RNAs by Cas12a itself (Zetsche et al., Reference Zetsche, Heidenreich, Mohanraju, Fedorova, Kneppers, Degennaro, Winblad, Choudhury, Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Wu, Scott, Severinov, Van Der Oost and Zhang2016).

Relative to the Cas9 family of Cas effectors, Cas12 is a much more diverse family. Indeed a number of subtypes of Cas12 systems have recently been reported (denoted type V-A – V-I). The Cas12b effectors (previously known as C2c1) target DNA, but in contrast to Cas12a, they are dual-RNA guided, requiring a tracrRNA (Shmakov et al., Reference Shmakov, Abudayyeh, Makarova, Wolf, Gootenberg, Semenova, Minakhin, Joung, Konermann, Severinov, Zhang and Koonin2015). Although initial characterization of Cas12b revealed thermophilic nuclease activity, which prevented application in mammalian cells, subsequent exploration of the Cas12b diversity and protein engineering made possible the development of two-Cas12b systems with robust genome editing activity in human cells (Teng et al., Reference Teng, Cui, Feng, Guo, Xu, Gao, Li, Li, Zhou and Li2018; Strecker et al., Reference Strecker, Jones, Koopal, Schmid-Burgk, Zetsche, Gao, Makarova, Koonin and Zhang2019). Comparison of Cas12b with SpCas9 showed that Cas12b has substantially reduced off-target activity, indicating it is inherently more specific than wild-type SpCas9 when targeting the human genome (Teng et al., Reference Teng, Cui, Feng, Guo, Xu, Gao, Li, Li, Zhou and Li2018; Strecker et al., Reference Strecker, Jones, Koopal, Schmid-Burgk, Zetsche, Gao, Makarova, Koonin and Zhang2019). Additional Cas12 effectors have also been identified from bacterial genomic databases, including Cas12c (Shmakov et al., Reference Shmakov, Abudayyeh, Makarova, Wolf, Gootenberg, Semenova, Minakhin, Joung, Konermann, Severinov, Zhang and Koonin2015), Cas12d (CasY) and Cas12e (CasX), both of which were found in metagenomic samples (Burstein et al., Reference Burstein, Harrington, Strutt, Probst, Anantharaman, Thomas, Doudna and Banfield2017), and three subtypes of Cas12f (Cas14) (Harrington et al., Reference Harrington, Burstein, Chen, Paez-Espino, Ma, Witte, Cofsky, Kyrpides, Banfield and Doudna2018). Two-Cas12e orthologs, DpbCasX and PlmCasX, have recently been shown to achieve targeted gene knockout in human cells (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Orlova, Oakes, Ma, Spinner, Baney, Chuck, Tan, Knott, Harrington, Al-Shayeb, Wagner, Brötzmann, Staahl, Taylor, Desmarais, Nogales and Doudna2019). A recent effort to holistically identify CRISPR-Cas systems from more than 10 terabytes of genomic and metagenomic data led to the identification of a number of new type V subtype loci, including both DNA- and RNA-targeting Cas12 systems (Yan et al., Reference Yan, Hunnewell, Alfonse, Carte, Keston-Smith, Sothiselvam, Garrity, Chong, Makarova, Koonin, Cheng and Scott2019).

Cas13

The type VI family of CRISPR-Cas systems, signified by the RNA-guided RNA-targeting Cas13 effector, was first found by using the highly conserved adaptation protein Cas1 as the search seed to identify all genomic fragments that contain putative CRISPR-Cas systems. Focusing on conserved proteins of unknown function located within each CRISPR locus, we discovered a family of well-conserved large proteins carrying the higher eukaryotic–prokaryotic nuclease (HEPN) domain, which suggested they are putative RNases (Shmakov et al., Reference Shmakov, Abudayyeh, Makarova, Wolf, Gootenberg, Semenova, Minakhin, Joung, Konermann, Severinov, Zhang and Koonin2015). Subsequent expansion of the search to use CRISPR repeats as the search seed led to the identification of additional Cas13 subtypes, including Cas13b, Cas13c, and Cas13d (Shmakov et al., Reference Shmakov, Smargon, Scott, Cox, Pyzocha, Yan, Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Makarova, Wolf, Severinov, Zhang and Koonin2017; Smargon et al., Reference Smargon, Cox, Pyzocha, Zheng, Slaymaker, Gootenberg, Abudayyeh, Essletzbichler, Shmakov, Makarova, Koonin and Zhang2017; Konermann et al., Reference Konermann, Lotfy, Brideau, Oki, Shokhirev and Hsu2018; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Chong, Zhang, Makarova, Koonin, Cheng and Scott2018b).

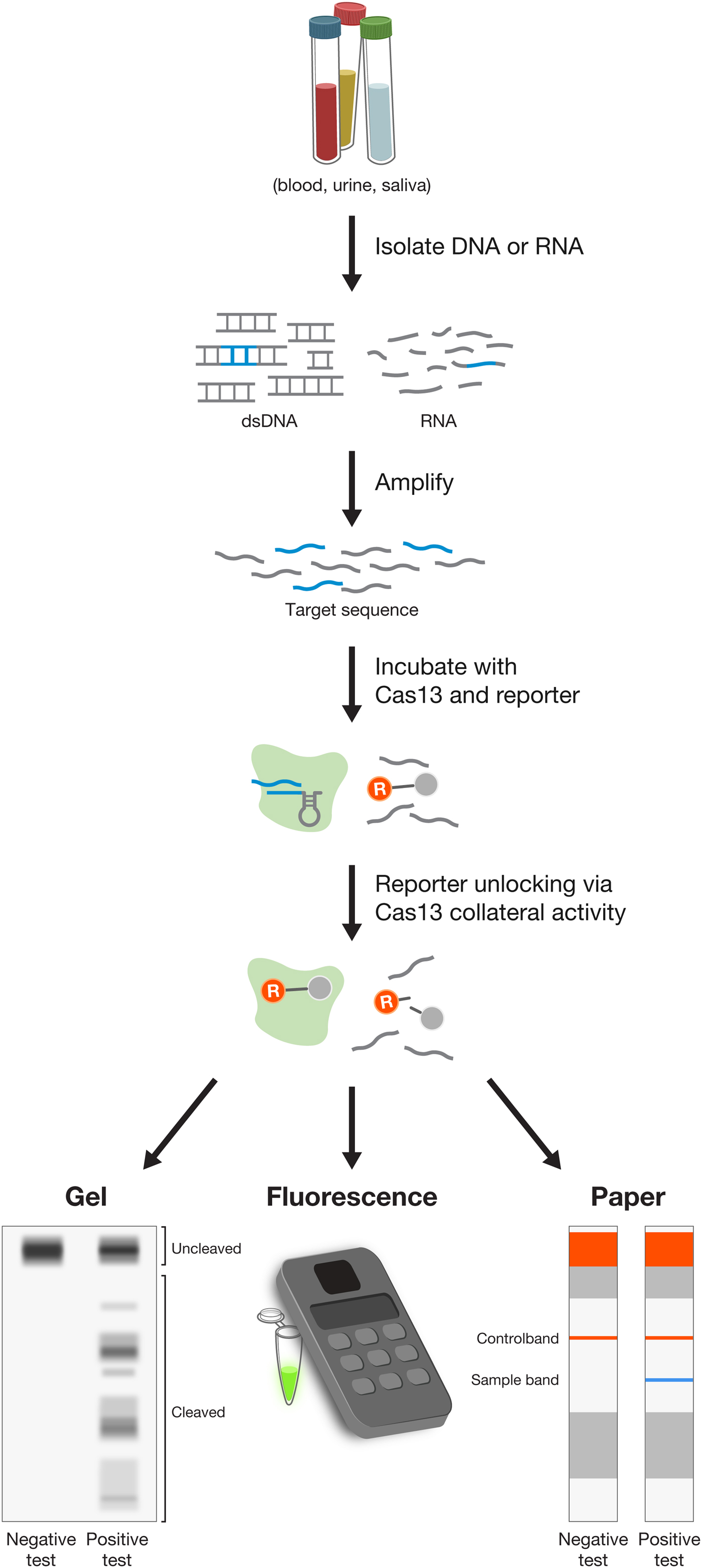

Using E. coli heterologously expressing type VI CRISPR-Cas systems, we showed that CRISPR-Cas13a and Cas13b systems confer resistance to RNA phages, and that they are single-effector RNases guided by crRNAs (Abudayyeh et al., Reference Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Konermann, Joung, Slaymaker, Cox, Shmakov, Makarova, Semenova, Minakhin, Severinov, Regev, Lander, Koonin and Zhang2016; Smargon et al., Reference Smargon, Cox, Pyzocha, Zheng, Slaymaker, Gootenberg, Abudayyeh, Essletzbichler, Shmakov, Makarova, Koonin and Zhang2017). This finding paved the way for an entirely new set of molecular technologies operating at the level of RNA, rather than DNA, and offering a safer therapeutic approach to treating disease (see below). Similar to Cas12a, Cas13 proteins also contain an RNase processing domain with the ability to cleave their corresponding CRISPR array into individual mature crRNAs (East-Seletsky et al., Reference East-Seletsky, O'connell, Knight, Burstein, Cate, Tjian and Doudna2016; Smargon et al., Reference Smargon, Cox, Pyzocha, Zheng, Slaymaker, Gootenberg, Abudayyeh, Essletzbichler, Shmakov, Makarova, Koonin and Zhang2017; Konermann et al., Reference Konermann, Lotfy, Brideau, Oki, Shokhirev and Hsu2018). Cas13 cleaves RNA at sites outside of the target region complementary to the crRNA. Analysis of cleavage products of Leptotrichia shahii Cas13a (LshCas13a) showed that cut sites do not vary even for crRNAs targeting different positions on the same target, indicating that cut sites are likely dictated by a combination of the target RNA secondary structure and sequence features (Abudayyeh et al., Reference Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Essletzbichler, Han, Joung, Belanto, Verdine, Cox, Kellner, Regev, Lander, Voytas, Ting and Zhang2017; Smargon et al., Reference Smargon, Cox, Pyzocha, Zheng, Slaymaker, Gootenberg, Abudayyeh, Essletzbichler, Shmakov, Makarova, Koonin and Zhang2017). Further exploration of the RNase activity uncovered the ‘collateral effect’ of Cas13 – recognition of the target RNA by the Cas13-crRNA complex leads Cas13 to become a promiscuous RNase, cleaving non-target bystander RNAs at preferred cut sites (Abudayyeh et al., Reference Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Konermann, Joung, Slaymaker, Cox, Shmakov, Makarova, Semenova, Minakhin, Severinov, Regev, Lander, Koonin and Zhang2016). Collateral activity may play a role in programmed cell death in bacteria, although this remains to be fully explored. This collateral activity has been exploited to expand the applications of Cas effectors into new categories, including the development of sensitive, low-cost, and rapid diagnostics assays for viral and bacterial infections (see below).

Cas13a, b, c, and d have all been adapted for use in mammalian cells to mediate targeted RNA knockdown (Abudayyeh et al., Reference Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Essletzbichler, Han, Joung, Belanto, Verdine, Cox, Kellner, Regev, Lander, Voytas, Ting and Zhang2017; Cox et al., Reference Cox, Gootenberg, Abudayyeh, Franklin, Kellner, Joung and Zhang2017; Konermann et al., Reference Konermann, Lotfy, Brideau, Oki, Shokhirev and Hsu2018). Interestingly, although in bacteria, each Cas13 ortholog exhibits varying levels of nucleotide preference in sequences flanking the protospacer, referred to as the protospacer flanking site (PFS), the presence of the PFS is not a strict requirement for RNA targeting in mammalian cells (Abudayyeh et al., Reference Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Essletzbichler, Han, Joung, Belanto, Verdine, Cox, Kellner, Regev, Lander, Voytas, Ting and Zhang2017). Additionally, although collateral activity has been observed in vitro and in bacterial cells (Abudayyeh et al., Reference Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Konermann, Joung, Slaymaker, Cox, Shmakov, Makarova, Semenova, Minakhin, Severinov, Regev, Lander, Koonin and Zhang2016; Meeske and Marraffini, Reference Meeske and Marraffini2018), it has not been detected in mammalian cells (Abudayyeh et al., Reference Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Essletzbichler, Han, Joung, Belanto, Verdine, Cox, Kellner, Regev, Lander, Voytas, Ting and Zhang2017; Konermann et al., Reference Konermann, Lotfy, Brideau, Oki, Shokhirev and Hsu2018), suggesting that, similarly for Cas9 and Cas12, the differences between biochemical, bacterial, and mammalian environments can substantially affect the behavior of Cas effectors.

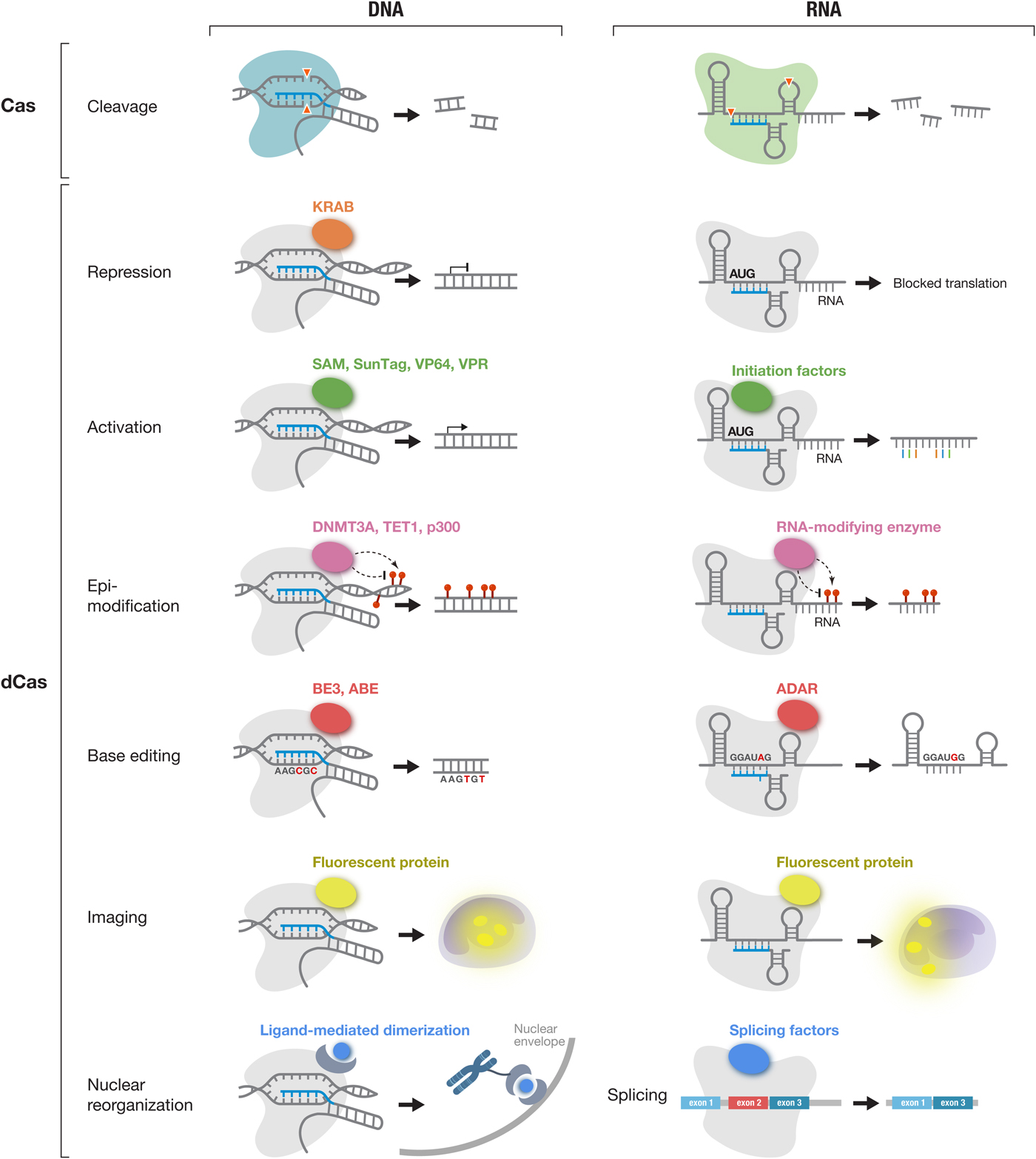

Development of a molecular toolbox based on Cas effectors

DNA and RNA cleavage through the nuclease activities of Cas effectors is only one way CRISPR technology can be applied. The ability to customize the binding specificity of Cas effectors using a short-guide RNA creates many additional opportunities for developing new capabilities for manipulating DNA and RNA. There are two-main categories of molecular tools based on Cas proteins (Fig. 5), with the first category utilizing the intrinsic RNA-guided nuclease activity of each effector, and the second category exploiting nuclease-inactivated Cas proteins (dCas) as RNA-guided nucleic acid binding domains to target effector modules to modulate, monitor, or modify target DNA or RNA. As tools based on Cas effectors rely on the specificity of RNA-guided target recognition, another area of focus has been to assess the specificity of Cas effectors as well as engineering solutions to enhance their specificity. Below is an overview of the broad range of molecular tools that have been developed based on Cas proteins as well as efforts to address the most critical challenges facing CRISPR-based tools.

Fig. 5. The CRISPR-Cas toolbox enables a broad range of applications in eukaryotic cells. Applications of DNA-targeting Cas effectors (Cas9 and Cas12a-e) (left column) and applications of RNA-targeting Cas effectors (Cas13a-d) (right column) are shown. Active Cas effectors can be used for nucleic acid cleavage. In addition, Cas effectors can be turned into RNA-guided DNA or RNA binding domains by inactivating their catalytic residues (dCas). dCas can be fused to a variety of functional moieties to achieve targeted repression, activation, epi-modification, base editing, and imaging at either the DNA or RNA level. In addition, dCas13 can be used to modulate splicing through fusion to splicing factors. KRAB, Krüppel associated box; SAM, synergistic activation module; SunTag, SUperNova Tag; DNMT3A, DNA methyltransferase 3 alpha; TET1, ten-eleven translocation 1; p300, E1A-associated protein p300; BE3, base editor 3; ABE, adenine base editor and ADAR, adenosine deaminase acting on RNA;.

Leveraging natural and engineered properties of diverse Cas effectors

The opportunities for developing Cas effectors as molecular technologies are further amplified by the natural diversity within each family of class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems. Based on the current publicly accessible bacterial genomic and metagenomic sequencing data, there are over 100 000 Cas9 family members, over 70 000 Cas12 family members, and over 5000 Cas13 family members. Within each family, members can exhibit a number of differences in terms of their size, guide RNA requirement, binding motif (e.g., PAM and PFS), targeting specificity, and suitability for function in eukaryotic cells. In the case of Cas13 family members, they can also exhibit different cleavage motif preferences.

A number of Cas9 orthologs have been discovered (Bolotin et al., Reference Bolotin, Quinquis, Sorokin and Ehrlich2005; Makarova et al., Reference Makarova, Haft, Barrangou, Brouns, Charpentier, Horvath, Moineau, Mojica, Wolf, Yakunin, Van Der Oost and Koonin2011, Reference Makarova, Wolf, Alkhnbashi, Costa, Shah, Saunders, Barrangou, Brouns, Charpentier, Haft, Horvath, Moineau, Mojica, Terns, Terns, White, Yakunin, Garrett, Van Der Oost, Backofen and Koonin2015; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Heidrich, Ampattu, Gunderson, Seifert, Schoen, Vogel and Sontheimer2013; Chylinski et al., Reference Chylinski, Makarova, Charpentier and Koonin2014; Fonfara et al., Reference Fonfara, Le Rhun, Chylinski, Makarova, Lécrivain, Bzdrenga, Koonin and Charpentier2014; Ran et al., Reference Ran, Cong, Yan, Scott, Gootenberg, Kriz, Zetsche, Shalem, Wu, Makarova, Koonin, Sharp and Zhang2015; Shmakov et al., Reference Shmakov, Smargon, Scott, Cox, Pyzocha, Yan, Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Makarova, Wolf, Severinov, Zhang and Koonin2017), and an increasing number of these have been developed for use as genome editing tools beyond SpCas9 and StCas9 (Esvelt et al., Reference Esvelt, Mali, Braff, Moosburner, Yaung and Church2013; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Zhang, Propson, Howden, Chu, Sontheimer and Thomson2013; Karvelis et al., Reference Karvelis, Gasiunas, Young, Bigelyte, Silanskas, Cigan and Siksnys2015; Ran et al., Reference Ran, Cong, Yan, Scott, Gootenberg, Kriz, Zetsche, Shalem, Wu, Makarova, Koonin, Sharp and Zhang2015; Hirano et al., Reference Hirano, Gootenberg, Horii, Abudayyeh, Kimura, Hsu, Nakane, Ishitani, Hatada, Zhang, Nishimasu and Nureki2016; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Cradick and Bao2016; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Koo, Park, Kim, Kim, Cho, Song, Lee, Jung, Kim, Kim, Kim and Kim2017a). The natural diversity of these enzymes has allowed expanded applications, for example some smaller Cas9 orthologs, such as S. aureus Cas9 (SaCas9), Neisseria meningitidis Cas9 (NmeCas9), and Campylobacter jejunii Cas9 (CjCas9) have been efficiently delivered in vivo using a single-vector strategy (Ran et al., Reference Ran, Cong, Yan, Scott, Gootenberg, Kriz, Zetsche, Shalem, Wu, Makarova, Koonin, Sharp and Zhang2015; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Koo, Park, Kim, Kim, Cho, Song, Lee, Jung, Kim, Kim, Kim and Kim2017a; Ibraheim et al., Reference Ibraheim, Song, Mir, Amrani, Xue and Sontheimer2018).

While exploration of natural Cas diversity provides one avenue for expanding and improving CRISPR-based tools, a complementary approach uses structure-guided engineering to modify and improve Cas effector function. Over the past several years a number of crystal structures have been solved for different members of Cas9 (Anders et al., Reference Anders, Niewoehner, Duerst and Jinek2014; Jinek et al., Reference Jinek, Jiang, Taylor, Sternberg, Kaya, Ma, Anders, Hauer, Zhou, Lin, Kaplan, Iavarone, Charpentier, Nogales and Doudna2014; Nishimasu et al., Reference Nishimasu, Ran, Hsu, Konermann, Shehata, Dohmae, Ishitani, Zhang and Nureki2014, Reference Nishimasu, Cong, Yan, Ran, Zetsche, Li, Kurabayashi, Ishitani, Zhang and Nureki2015; Hirano et al., Reference Hirano, Gootenberg, Horii, Abudayyeh, Kimura, Hsu, Nakane, Ishitani, Hatada, Zhang, Nishimasu and Nureki2016; Yamada et al., Reference Yamada, Watanabe, Gootenberg, Hirano, Ran, Nakane, Ishitani, Zhang, Nishimasu and Nureki2017), Cas12 (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Ren, Qiu, Zheng, Guo, Guan, Liu, Li, Zhang, Yang, Ma, Wang, Wu, Ma, Fan, Wang, Gao and Huang2016; Yamano et al., Reference Yamano, Nishimasu, Zetsche, Hirano, Slaymaker, Li, Fedorova, Nakane, Makarova, Koonin, Ishitani, Zhang and Nureki2016; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Gao, Rajashankar and Patel2016; Stella et al., Reference Stella, Alcón and Montoya2017; Swarts et al., Reference Swarts, Van Der Oost and Jinek2017; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Guan, Zhu, Ren and Huang2017; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Orlova, Oakes, Ma, Spinner, Baney, Chuck, Tan, Knott, Harrington, Al-Shayeb, Wagner, Brötzmann, Staahl, Taylor, Desmarais, Nogales and Doudna2019), and Cas13 (Knott et al., Reference Knott, East-Seletsky, Cofsky, Holton, Charles, O'connell and Doudna2017; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Li, Ma, Li, You, Wang, Wang, Zhang and Wang2017a, Reference Liu, Li, Wang, Wang, Chen, Yin, Li, Sheng and Wang2017b; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Ye, Ye, Zhou, Saeed, Chen, Lin, Perčulija, Chen, Chen, Chang, Choudhary and Ouyang2018a, Reference Zhang, Konermann, Brideau, Lotfy, Wu, Novick, Strutzenberg, Griffin, Hsu and Lyumkis2018b; Slaymaker et al., Reference Slaymaker, Mesa, Kellner, Kannan, Brignole, Koob, Feliciano, Stella, Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Strecker, Montoya and Zhang2019) families. These structures include the apo forms with just the effector protein alone, or the effector in complex with its guide RNA alone or guide RNA in complex with target DNA or RNA, providing structural insights into target recognition and cleavage. These structural studies have been complemented by other biochemical and biophysical studies into the target search mechanism of Cas effectors (Sternberg et al., Reference Sternberg, Redding, Jinek, Greene and Doudna2014; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Xie, Deng, Guglielmi, Witkowsky, Bosanac, Zhang, El Beheiry, Masson, Dahan, Liu, Doudna and Tjian2015; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Tu, Naseri, Huisman, Zhang, Grunwald and Pederson2016a).

Expanding the targeting range of DNA-targeting Cas proteins

The DNA targeting range of Cas9 and Cas12 is defined by the PAM sequence, a short-sequence flanking the target sequence is required for DNA targeting. A shorter PAM sequence provides a broader targeting range whereas longer PAM sequences are more restrictive. For example, wild-type SpCas9 (which has an NGG PAM) can target roughly ten times more sites in the human exome than wild-type SaCas9 (which has an NNGRRT PAM) (Scott and Zhang, Reference Scott and Zhang2017). In order to increase the flexibility of Cas-mediated DNA targeting, a combination of approaches has been used to expand the number of targetable PAM sequences. First, by exploring phylogenetic diversity, a number of Cas effector orthologs have been identified with distinct PAM requirements. In the case of Cas12a, a survey of more than a dozen orthologs identified one, from Moraxella bovoculi, with robust indel activity in human cells and tolerance of a shorter PAM, expanding the available targeting landscape (Zetsche et al., Reference Zetsche, Strecker, Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Scott and Zhang2017). Ultimately, however, only a handful of Cas effectors have been successfully developed for function in eukaryotic cells (Ran et al., Reference Ran, Cong, Yan, Scott, Gootenberg, Kriz, Zetsche, Shalem, Wu, Makarova, Koonin, Sharp and Zhang2015; Zetsche et al., Reference Zetsche, Gootenberg, Abudayyeh, Slaymaker, Makarova, Essletzbichler, Volz, Joung, Van Der Oost, Regev, Koonin and Zhang2015a; Abudayyeh et al., Reference Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Essletzbichler, Han, Joung, Belanto, Verdine, Cox, Kellner, Regev, Lander, Voytas, Ting and Zhang2017; Cox et al., Reference Cox, Gootenberg, Abudayyeh, Franklin, Kellner, Joung and Zhang2017; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Koo, Park, Kim, Kim, Cho, Song, Lee, Jung, Kim, Kim, Kim and Kim2017a; Chatterjee et al., Reference Chatterjee, Jakimo and Jacobson2018; Ibraheim et al., Reference Ibraheim, Song, Mir, Amrani, Xue and Sontheimer2018; Konermann et al., Reference Konermann, Lotfy, Brideau, Oki, Shokhirev and Hsu2018; Teng et al., Reference Teng, Cui, Feng, Guo, Xu, Gao, Li, Li, Zhou and Li2018; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Orlova, Oakes, Ma, Spinner, Baney, Chuck, Tan, Knott, Harrington, Al-Shayeb, Wagner, Brötzmann, Staahl, Taylor, Desmarais, Nogales and Doudna2019; Strecker et al., Reference Strecker, Jones, Koopal, Schmid-Burgk, Zetsche, Gao, Makarova, Koonin and Zhang2019) limiting the extent of this approach.

A second approach for expanding the DNA targeting range of Cas9 and Cas12 is to engineer new variants, either through structure-guided design or directed evolution. Based on the crystal structures of Cas effectors in complex with guide RNA and target DNA (Anders et al., Reference Anders, Niewoehner, Duerst and Jinek2014; Nishimasu et al., Reference Nishimasu, Cong, Yan, Ran, Zetsche, Li, Kurabayashi, Ishitani, Zhang and Nureki2015; Yamano et al., Reference Yamano, Nishimasu, Zetsche, Hirano, Slaymaker, Li, Fedorova, Nakane, Makarova, Koonin, Ishitani, Zhang and Nureki2016), targeted mutagenesis has been used to generate new protein variants with altered PAM sequences. At the same time, a number of groups have used directed evolution strategies to evolve new variants of Cas effectors with unique properties, including different PAM preferences. These efforts have led to the development of a number of Cas9 and Cas12a variants with a significantly broadened DNA targeting range (Kleinstiver et al., Reference Kleinstiver, Prew, Tsai, Nguyen, Topkar, Zheng and Joung2015a, Reference Kleinstiver, Prew, Tsai, Topkar, Nguyen, Zheng, Gonzales, Li, Peterson, Yeh, Aryee and Joung2015b; Gao et al., Reference Gao, Cox, Yan, Manteiga, Schneider, Yamano, Nishimasu, Nureki, Crosetto and Zhang2017; Hu et al., Reference Hu, Miller, Geurts, Tang, Chen, Sun, Zeina, Gao, Rees, Lin and Liu2018; Nishimasu et al., Reference Nishimasu, Shi, Ishiguro, Gao, Hirano, Okazaki, Noda, Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Mori, Oura, Holmes, Tanaka, Seki, Hirano, Aburatani, Ishitani, Ikawa, Yachie, Zhang and Nureki2018). Collectively, these variants enable targeting of virtually any genomic site.

Assessing the specificity of class 2 Cas effectors

One of the most critical technical requirements for the application of class 2 Cas effectors is their targeting specificity. When applying Cas9 or Cas12 as an active nuclease, minimizing off targets is particularly important because a range of undesirable genomic alterations could arise through the cell's endogenous DNA repair mechanisms, such as translocations between different cleavage sites and large-scale deletions. For nuclease as well as dCas binding applications, it is important that the effector binds selectively to the DNA or RNA targeted by the guide RNA. In the case of active nuclease applications, off-target editing activity due to pseudo-specific interactions between the Cas effector and the genome (arising when there are less than perfect matches between the target and guide RNA) can give rise to additional DSBs that lead to either small insertions and deletions (indels) or larger genomic alterations.

An initial study to characterize off-target indels used computational analyses to identify loci in the genome that share a high degree of homology to the target site, and then assayed editing events at these computationally predicted off-target loci using deep sequencing (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Foden, Khayter, Maeder, Reyon, Joung and Sander2013). The study found that SpCas9 can indeed induce off-target edits at genomic loci that carried three or fewer mismatches compared with the guide sequence. Additional studies using different approaches also showed that Cas9 can indeed introduce off-target edits (Hsu et al., Reference Hsu, Scott, Weinstein, Ran, Konermann, Agarwala, Li, Fine, Wu, Shalem, Cradick, Marraffini, Bao and Zhang2013; Mali et al., Reference Mali, Aach, Stranges, Esvelt, Moosburner, Kosuri, Yang and Church2013a; Pattanayak et al., Reference Pattanayak, Lin, Guilinger, Ma, Doudna and Liu2013). As the early approaches covered only a very limited set of off-target sites, subsequent investigations focused on developing genome-wide unbiased approaches including in vitro assays like Digenome-seq (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Bae, Park, Kim, Kim, Yu, Hwang, Kim and Kim2015), CIRCLE-seq (circularization for in vitro reporting of cleavage effects by sequencing) (Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Nguyen, Malagon-Lopez, Topkar, Aryee and Joung2017), and SITE-seq (selective enrichment and identification of tagged genomic DNA ends by sequencing) (Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Fuller, Donohoue, Jones, Thompson, Carter, Gradia, Vidal, Garner, Slorach, Lau, Banh, Lied, Edwards, Settle, Capurso, Llaca, Deschamps, Cigan, Young and May2017) and cellular assays like GUIDE-seq (genome-wide, unbiased identification of DSBs enabled by sequencing) (Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Zheng, Nguyen, Liebers, Topkar, Thapar, Wyvekens, Khayter, Iafrate, Le, Aryee and Joung2015), BLESS (direct in situ breaks labeling, enrichment on streptavidin and next-generation sequencing) and BLISS (breaks labeling in situ and sequencing) (Crosetto et al., Reference Crosetto, Mitra, Silva, Bienko, Dojer, Wang, Karaca, Chiarle, Skrzypczak, Ginalski, Pasero, Rowicka and Dikic2013; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Mirzazadeh, Garnerone, Scott, Schneider, Kallas, Custodio, Wernersson, Li, Gao, Federova, Zetsche, Zhang, Bienko and Crosetto2017), linear amplification-mediated PCR followed by high-throughput genome-wide translocation sequencing (LAM-HTGTS) (Frock et al., Reference Frock, Hu, Meyers, Ho, Kii and Alt2015), and VIVO (verification of in vivo off-targets) (Akcakaya et al., Reference Akcakaya, Bobbin, Guo, Malagon-Lopez, Clement, Garcia, Fellows, Porritt, Firth, Carreras, Baccega, Seeliger, Bjursell, Tsai, Nguyen, Nitsch, Mayr, Pinello, Bohlooly, Aryee, Maresca and Joung2018). The use of these assays found that the editing specificity of SpCas9 varied widely depending on the guide RNA. When these unbiased techniques were used to profile the specificity of Cas9 orthologs as well as Cas12 family members, it was found that SaCas9 as well as Cas12a and Cas12b are much more specific than SpCas9, with most guide RNAs exhibiting no detectable off-target editing (Kleinstiver et al., Reference Kleinstiver, Tsai, Prew, Nguyen, Welch, Lopez, Mccaw, Aryee and Joung2016b; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Mirzazadeh, Garnerone, Scott, Schneider, Kallas, Custodio, Wernersson, Li, Gao, Federova, Zetsche, Zhang, Bienko and Crosetto2017; Strohkendl et al., Reference Strohkendl, Saifuddin, Rybarski, Finkelstein and Russell2018; Tycko et al., Reference Tycko, Barrera, Huston, Friedland, Wu, Gootenberg, Abudayyeh, Myer, Wilson and Hsu2018; Strecker et al., Reference Strecker, Jones, Koopal, Schmid-Burgk, Zetsche, Gao, Makarova, Koonin and Zhang2019). It is worth noting, however, that the functional impact of off-target edits will vary depending on their location. For example, off-target indels within coding regions, regulatory elements, and non-coding RNAs are likely to have more undesirable effects.

A number of studies have also explored the landscape of larger genomic alterations arising from Cas9 activity. For translocations, the use of LAM-HTGTS showed that the frequency of SpCas9-induced translocation varies considerably with the guide RNA, from undetectable to ~3% (Frock et al., Reference Frock, Hu, Meyers, Ho, Kii and Alt2015), and the use of a tagmentation strategy found SpCas9-mediated translocation rates of ~2·5% for two-different guides (Giannoukos et al., Reference Giannoukos, Ciulla, Marco, Abdulkerim, Barrera, Bothmer, Dhanapal, Gloskowski, Jayaram, Maeder, Skor, Wang, Myer and Wilson2018). For large deletions, the use of PacBio and Sanger sequencing with SpCas9-edited hemizygous embryonic stem cells showed that 10 out of 48 edited alleles represented deletions larger than 250 bp (ranging up to nearly 6 kb) (Kosicki et al., Reference Kosicki, Tomberg and Bradley2018). The same study also identified a number of other events such as transversions, duplications, and other structural rearrangements (Kosicki et al., Reference Kosicki, Tomberg and Bradley2018).

Similar approaches have not been applied to the high-specificity variants of Cas9 or to Cas12a/b, all of which show substantially fewer indel off-targets, and it will be interesting to see if the number of large deletions and structural rearrangements is similarly reduced with these other Cas effectors. These studies, along with empirical testing of guide RNAs, will inform the best choice of the Cas effector for applications requiring particularly high levels of editing specificity. In addition, methods have been developed to quantify the on-target editing outcomes of Cas9 (Miyaoka et al., Reference Miyaoka, Berman, Cooper, Mayerl, Chan, Zhang, Karlin-Neumann and Conklin2016, Reference Miyaoka, Mayerl, Chan and Conklin2018).

When assessing the RNA targeting specificity of Cas13, the considerations are slightly different. Although off-target cleavage arising from pseudo-specific binding remains a concern, an additional issue with Cas13 is potential collateral cleavage of bystander transcripts. To assess the likelihood of off-target RNA knockdown, the effect of an increasing number of mismatches between the guide sequence and its RNA target was examined. From these studies it was found that Cas13 can tolerate up to a single mismatch throughout the guide sequence and still cleave the target RNA (Abudayyeh et al., Reference Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Essletzbichler, Han, Joung, Belanto, Verdine, Cox, Kellner, Regev, Lander, Voytas, Ting and Zhang2017). Additionally, transcriptome-wide sequencing revealed that Cas13 can achieve highly specific knockdown of the target transcript without significant off-target effects. In contrast, short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) knockdown of the same transcript led to downregulation of hundreds of off-targets (Abudayyeh et al., Reference Abudayyeh, Gootenberg, Essletzbichler, Han, Joung, Belanto, Verdine, Cox, Kellner, Regev, Lander, Voytas, Ting and Zhang2017). In addition, biochemical analysis of target RNA binding by Cas13a revealed that perfect matching in a central seed region of the guide sequence is required for binding, but a different guide region is required for the activation of RNase activity (Tambe et al., Reference Tambe, East-Seletsky, Knott, Doudna and O'connell2018). Together, these studies provided detailed insight into the potential off-target effects due to pseudo-specific binding as well as suggested that collateral activity is not significant in mammalian cells, which has been supported by additional studies (Konermann et al., Reference Konermann, Lotfy, Brideau, Oki, Shokhirev and Hsu2018).

Improving the targeting specificity of Cas effectors

A number of approaches have been developed to improve the specificity of DNA editing by Cas9, and many of these approaches have also been applied or are relevant to Cas12 as well. The approaches can be divided into strategies that either seek to reduce overall exposure to the nuclease or directly improve specificity through engineering of the system.

For the first category of approaches, we observed early on that the editing specificity can be improved by more than 10-fold by introducing less Cas9 into cells (Hsu et al., Reference Hsu, Scott, Weinstein, Ran, Konermann, Agarwala, Li, Fine, Wu, Shalem, Cradick, Marraffini, Bao and Zhang2013). In agreement with this observation, several other groups have demonstrated that using either mRNA to deliver Cas9 or delivering Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes directly into the target cell can significantly increase the editing specificity (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Kim, Kim, Kweon, Kim, Bae and Kim2014; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Staahl, Alla and Doudna2014). In addition to use of different delivery methods to limit the dosage of Cas9 in cells, it is also possible to engineer Cas9 so that its nuclease activity becomes drug- or light-inducible (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Pattanayak, Thompson, Zuris and Liu2015; Nihongaki et al., Reference Nihongaki, Kawano, Nakajima and Sato2015; Truong et al., Reference Truong, Kühner, Kühn, Werfel, Engelhardt, Wurst and Ortiz2015; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Sternberg, Taylor, Staahl, Bardales, Kornfeld and Doudna2015; Zetsche et al., Reference Zetsche, Volz and Zhang2015b; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ramli, Woo, Wang, Zhao, Zhang, Yim, Chong, Gowher, Chua, Jung, Lee and Tan2016a; Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Miyaoka, Gilbert, Mayerl, Lee, Weissman, Conklin and Wells2016; Rose et al., Reference Rose, Stephany, Valente, Trevillian, Dang, Bielas, Maly and Fowler2017). This inducible approach has also been applied to Cas12a (Tak et al., Reference Tak, Kleinstiver, Nuñez, Hsu, Horng, Gong, Weissman and Joung2017).

For the second category of approaches, various strategies have been used, beginning with engineering the system to increase the number of target DNA bases that must be specifically recognized by Cas9 in order to activate nuclease activity. The first strategy doubles the number of DNA bases that need to be recognized to introduce a DSB by utilizing a Cas9 nickase and two-juxtaposed guide RNAs to create two off-set nicks (Mali et al., Reference Mali, Aach, Stranges, Esvelt, Moosburner, Kosuri, Yang and Church2013a; Ran et al., Reference Ran, Hsu, Lin, Gootenberg, Konermann, Trevino, Scott, Inoue, Matoba, Zhang and Zhang2013). This method was found to reduce off-target edits beyond the detection limit (Ran et al., Reference Ran, Hsu, Lin, Gootenberg, Konermann, Trevino, Scott, Inoue, Matoba, Zhang and Zhang2013). Related to this double-nicking approach, a second strategy uses dCas9-FokI fusions and a pair of juxtaposed guide RNAs to facilitate the introduction of a DSB (Guilinger et al., Reference Guilinger, Thompson and Liu2014; Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Wyvekens, Khayter, Foden, Thapar, Reyon, Goodwin, Aryee and Joung2014). The specificity of Cas9 targeting can also be enhanced by modifying the guide RNA. One study showed that SpCas9 targeting can be significantly improved using truncated-guide RNAs with 17 nt of the targeting sequence (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Sander, Reyon, Cascio and Joung2014), which decreases the tolerance for mismatches. More recently, it was shown that the use of bridged or locked-nucleic acids can also improve Cas9 specificity by slowing the reaction rate (Cromwell et al., Reference Cromwell, Sung, Park, Krysler, Jovel, Kim and Hubbard2018), and that engineering the guide RNA to create a hairpin in the spacer region improves specificity of a number of Cas9 and Cas12 enzymes (Kocak et al., Reference Kocak, Josephs, Bhandarkar, Adkar, Kwon and Gersbach2019).

In addition to these strategies, rational engineering of Cas9 and Cas12 has been used to create high-specificity variants, offering a simpler solution to the specificity challenge. We developed the first of these variants, eSpCas9, which exhibits substantially reduced off-target activity while maintaining on-target efficiency (Slaymaker et al., Reference Slaymaker, Gao, Zetsche, Scott, Yan and Zhang2015). A number of groups have subsequently used structural information or directed evolution to develop additional high-specificity variants of Cas9 (Kleinstiver et al., Reference Kleinstiver, Pattanayak, Prew, Tsai, Nguyen, Zheng and Joung2016a; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Dagdas, Kleinstiver, Welch, Sousa, Harrington, Sternberg, Joung, Yildiz and Doudna2017; Casini et al., Reference Casini, Olivieri, Petris, Montagna, Reginato, Maule, Lorenzin, Prandi, Romanel, Demichelis, Inga and Cereseto2018; Hu et al., Reference Hu, Miller, Geurts, Tang, Chen, Sun, Zeina, Gao, Rees, Lin and Liu2018; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Jeong, Lee, Jung, Shin, Kim, Lee, Jung, Kim, Kim and Kim2018; Vakulskas et al., Reference Vakulskas, Dever, Rettig, Turk, Jacobi, Collingwood, Bode, Mcneill, Yan, Camarena, Lee, Park, Wiebking, Bak, Gomez-Ospina, Pavel-Dinu, Sun, Bao, Porteus and Behlke2018) and Cas12a (Kleinstiver et al., Reference Kleinstiver, Sousa, Walton, Tak, Hsu, Clement, Welch, Horng, Malagon-Lopez, Scarfo, Maus, Pinello, Aryee and Joung2019).