1. Introduction

1.1. The review and motivation for it

This review is the result of an extensive internet-based search for accounts about traditional astronomy conceptions held by Aboriginal peoples whose country is completely, or partly, in Western Australia (WA). The search for information was initially to support an art project (Mount Magnet Quilt Project Group 2019), then gained momentum when a key document in the field, Dawes Review 5: Australian Aboriginal Astronomy and Navigation (Norris Reference Norris2016), which is national in scope, offered many references for the eastern states and the Northern Territory, but few for WA.

1.2. Scope of Aboriginal astronomy

Aboriginal peoples, Australia-wide, named the Sun, Moon, individual stars, constellations, planets, the Magellanic galaxies, as well as dark spaces in the sky. Objects in the sky were used traditionally to establish direction, guide navigation, predict seasonal change, as time-keepers and as calendars for arranging social life. Narratives told by Aboriginal peoples link creation of objects in the sky with life on earth and link landforms on earth with objects in the sky. Other narratives about objects in the sky guide behaviour. All the aspects mentioned indicate an holistic world-view that encompasses the sky world, life on earth and landforms on earth.

1.3. Limitations of this review

This review is mainly based on documents and published papers that are available online. Publications that require special access in restricted collections generally were not accessed. Further, whether or not current accounts by Aboriginal people reveal knowledge which is free of European influence is a moot point, and narratives evolve over time, adapted by people who tell them (Kelly Reference Kelly2016). In particular, narratives reclaimed by Elders, after the cultural impact of several generations of stolen children, may differ from those told pre-European settlement. So, birth year if known is stated when Elders are first referenced, to indicate the period when narratives and knowledge were handed down to them.

Another contingency is that archivists and researchers may overlay their own world views when collecting and interpreting data. However, the peer-reviewed papers and accepted theses that are cited conform to normal academic standards. Non-traditional sources have also been referenced, including storybooks and artist statements. They were selected on the basis that the authors are Aboriginal, and the references complement other sources of information. They are clearly identified for the critical reader. Justification for storybook references, as Noongar Elder Dr Noel Nannup OAM (b. 1948) explains (Robertson et al. Reference Robertson, Stasiuk, Nannup and Hopper2016), is that stories for children are part of the fabric of Aboriginal peoples’ perceptions, albeit that more layers of meaning are revealed as children grow in maturity and knowledge.

1.4. Review organisation and references

The subjects covered mirror those in the Dawes Review 5 (Norris Reference Norris2016). This was done so that interested readers could easily read this paper in conjunction with the Dawes Review. Generally, each section starts with a brief summary of content from the Dawes Review, then discusses the topic from a WA perspective.

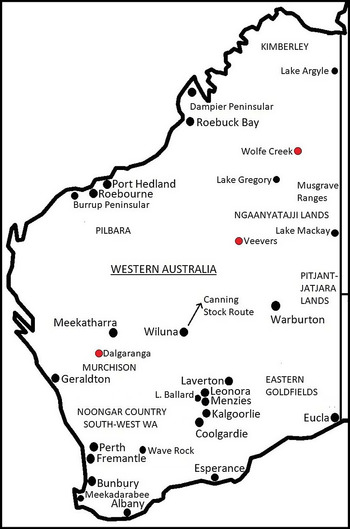

More references were sourced for Noongar Country in the south-west than for other regions of WA. The spelling of Noongar in the review varies – each version matches that in the papers from which the references were retrieved. Noongar Country is approximately triangular with boundaries from Geraldton, down the west coast of WA and east along the south coast to Esperance: Esperance to Geraldton is the third side of the triangle (see Figure 1). Noongar Country has fourteen language groups. Their territories are identified on a map by Tindale (Reference Tindale1940). Other major areas from which references are drawn are Wongai (Wongatha) Country (Eastern Goldfields, south-east WA), Yamatji Country (the Murchison, mid-west WA), the Pilbara (north-west WA), the Kimberley (north WA) and Pitjantjatjara and Ngaanyatajja Lands (Central Desert areas) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of Western Australia with localities mentioned in the text. Meteorite craters are marked in red. Generated by P. Forster using ’Australia states blank.png’, GNU Free Documentation License.

To judge what might be completely Aboriginal versus European-influenced conceptions of the night sky, the reader needs to know that the first European settlement in WA was in the south-west, at Albany on the south coast in 1826, followed by proclamation, in 1829, of the Swan River Colony which included Perth. Noongar vocabularies, mainly drawn from First People in and around Perth, and quoted here, were published early on by Lyon (Reference Lyon1833), Grey (Reference Grey1840) and Moore (Reference Moore1842). Publication of diaries and journals written during early settlement was often delayed, for example, Moore (Reference Moore1884) and posthumously for Salvado (Reference Salvado1977), who landed in Fremantle in 1846 and lived most years until 1900 in New Norcia, 130 km north of Perth. Ethel Hassell (1857–1933) settled on the south-east coast of Noongar country in 1878 and wrote sketches of her experiences with Wheelman Noongar people. Her journal, Hassell (Reference Hasselln.d.)Footnote a , is drawn on in this review, rather than edited versions of it. The writings of amateur anthropologist Daisy Bates CBE (1859–1951), of Irish descent, who camped with Aboriginal people in WA and South Australia for 20 yr from 1899, are also referenced.

1.5. Significance of the review

This review addresses a gap in the literature by providing a broad overview of WA Aboriginal astronomy perspectives that have been identified through research, together with insights gained from non-academic sources. It potentially will serve as a reference for future research in WA and for preparation of future overviews that are national in scope.

Further, a radio-quiet remote site in Yamatji Country (the Murchison, mid-west WA) has been chosen for the International Square Kilometre Array (SKA) project. The SKA will be the world’s biggest ground-based telescope array. From moral and practical perspectives, the SKA demands recognition and understanding of Yamatji astronomical traditions, together with an appreciation of Aboriginal astronomy generally. Significantly, this review could support conversations and arrangements with Yamatji people and the production of education materials for the general public.

2. Aboriginal number systems

Norris (Reference Norris2016) cites Blake’s (Reference Blake1981) claim that no Aboriginal language has a word for a number higher than four. Daisy Bates (Reference Batesn.d. a: 4) held a similar view, for WA Aboriginal peoples that she encountered:

The W.A. numerals count no higher than three … Sometimes the natives will hold up a hand for ‘five’, and in rare cases the two hands for ‘ten’, but any number beyond that is a ‘great many’.

However, Norris (Reference Norris2016) supplies cardinal numbers as counter evidence for Blake’s claim and notes that base five counting is common. Numbers in Moore’s (Reference Moore1842: 37–101) Noongar vocabulary also reflect base-five form: the number words are linked linguistically to the words for Marhra, the hand, and Jinna, the foot and a word for half is included:

Gyn Adjective One.

Dombart Adjective Alone; one; single.

Gudgal Numeral; two.

Warh-rang Numeral; three.

Mardyn (Northern word) Three.

Murtden (King George Sound) Three.

Gudjalingudjalin Numeral; four.

Bang-ga Part of; half of anything.

Marh-jin-bang-ga Five; literally, half the hands.

Marh-jin-bang-ga-gudjir-gyn Six; literally, half the hands and one.

Marh-jin-bang-ga gudjir-Gudjal Seven.

Marh-jin-belli-belli-Gudjir-jina-bangga Fifteen; literally, the hand on either side, and half the feet.

The Counting Poster (Noongar Boodjar Language Cultural Aboriginal Corporation, n.d.) prepared in consultation with Noongar people, and in current use in WA schools, reflects Moore’s (Reference Moore1842) record. Differences between the poster entries and the oral language recorded by Moore are mostly phonetic or involve simplification of compound words.

Traditionally, Noongar people might have had notional understanding of a quarter and three-quarters, because Moore (Reference Moore1842) lists words for phases of the moon: moon waxing – new moon, first quarter, half moon, second quarter, full moon and moon waning – three quarters, half moon and last quarter. In listing the words, Moore included the proviso that ‘… the meaning of several terms has not been distinctly ascertained.’ (ibid: 73). Certainly, the word for half-moon (moon waxing) Bangal is linked linguistically to the word Bang-ga, half of anything.

Moore’s (Reference Moore1842) vocabulary also has words for ordinal numbers and ordered things, for example:

First Gorijat; Gwadjat; Gwytchangat. (ibid: 133).

Kardijit … the second son, also the middle finger. (ibid: 56).

Kardang Younger brother; third son; also third finger. (ibid: 56).

As well, the vocabulary has words for two or more objects including ngalla for brother and sister, or two friends.

Consistent with most other findings for Aboriginal number systems Australia-wide (Norris Reference Norris2016), there are no words in the Noongar vocabularies of Lyon (Reference Lyon1833), Grey (Reference Grey1840) or Moore (Reference Moore1842) for higher numbers such as one hundred. However, there is a word for many or abundant: ‘Bula Abundant; many; much; plentiful.’ (Moore Reference Moore1842: 15). Also, Moore (Reference Moore1884: 225) recorded the following:

Today I find that a great sensation has been created in the colony by rumours which have come to us, only through the natives, of a vessel that was wrecked nearly six months ago (30 d journey, as they described it) to the North of this—which is conjectured to be about Sharks Bay.

It would be interesting to know how 30 was spoken or gestured.

3. Sun, Moon and Eclipses

3.1. The Sun

Commonly, Aboriginal people across Australia view the Sun as a female spirit who carries lighted wood from east to west across the sky (Norris Reference Norris2016). Others cast the Sun as a woman, chasing or being chased by the Moon-man (Hamacher & Norris Reference Hamacher and Norris2011a). A narrative from New South Wales describes how the Sun was created by the throwing of an emu egg which broke and caused a fire (Parker Reference Parker1898).

Macintyre and Dobson’s (Reference Macintyre and Dobson2017a) linguistic analysis of Noongar words fits the notion of lighted wood carried across the sky. They link Moore’s (Reference Moore1842) Whadjuk Noongar word biryt, for daylight, with the word birytch, for cone of a banksia, which women carried smouldering between campsites, under their cloaks, to act as a firelighter. Other Noongar words in Moore’s vocabulary that support the Sun – fire link are malyar, the ignited portion of a piece of burning wood; and malyarak, mid-day. See Figure 2 for the fire being extinguished.

Figure 2. Sunset, from Cape Leveque, west Kimberley. Photograph by J. Forster.

In three WA narratives, the Sun is cast as the giver of life. In 1830, Mokare (c. 1800–1831), a Minang Noongar leader (south coast) shared a creation narrative with Captain Collet Barker (Commandant of the penal settlement at Albany, south coast WA, 1829–1831):

… he told me that a very long time ago the only person living was an old woman named Annegar … who had a beard as large as the garden. She was delivered of a daughter & then died. The daughter called Moerang grew up in the course of time to be a woman, when she had several children … who were the fathers & mothers of all the black people. (Barker Reference Barker1830, in Macintyre & Dobson Reference Macintyre and Dobson2017a).

Macintyre and Dobson conjecture that Annegar may equate with arnga, meaning the beard, which according to Grey (Reference Grey1840) is a corruption of nanga. Grey does not list the meaning of nanga, but does list nganga, the sun and ngangan a mother. Macintyre and Dobson point out that the meaning of all the words mentioned depends on context, and that the name Annegar could mean the bearded sun woman.

Whadjuk/Balardong Noongar Professor Len Collard (b. 1959), University of Western Australia, recorded the narrative ‘The Walitj the Eagle, Kulbardi the Magpie, Wardong the Crow and Djidi the Willy Wagtail’, told to him, in the oral tradition, by his Aunty Janet Hayden:

When darkness came over the earth, they [the birds] had no way of bringing light back, and the sun wouldn’t come back. They had to send a bird and all the birds volunteered…. They had to fly as high as they possibly could … They found old Gnarnk … They brought the sun back. They told her that without her the earth would die. She was the Giver, they called her the sun, the Giver of Life. (Collard Reference Collard2009: 14–15).

Perhaps the birds’ dawn chorus, which starts just before dawn, brought/brings the sun back?

Jakayu Biljabu (b. 1937) of the Martu people, east Pilbara, was born near Pitu, east of Well 25 on the Canning Stock Route (see Figure 1) and lived with her family longer than most before leaving the traditional life (Martumili Artists Reference Martumili2021a). The statement for her painting Nyilangkurr Claypan n.d. (Estrangin Gallery Reference Estrangin2021a), a claypan which is close to Well 25, includes a brief outline of a Dreamtime narrative for the area. In it, the world is dark, the Sun comes up and life forms develop.

In summary, the above WA characterisations of the Sun illustrate Natale’s (Reference Natale2012) premise that Aboriginal narratives work within an analogical framework – a female Sun who bears children, is a giver of life and carrier of burning wood (smouldering banksia cones), so performs the traditional roles of Aboriginal women; and the birds bring her back each morning.

Josie Boyle (c. 1943–2020), Wongai Elder, Eastern Goldfields, provided a slightly different description (Boyle Reference Boyle2007). Josie told narratives handed down by her mother who followed traditional ways for much of her life (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith2014). Creation, in brief, was when: the creator (Jindoo the Sun) sent two spirit men down from the Milky Way to shape the Earth. They made landforms and oceans. Then Jindoo sent seven sisters, stars of the Milky Way, to beautify the Earth with flowers, trees, birds, animals and creepy things.

Other references to the Sun in this review move away from the analogical. In Yindjibarndi Country, the Pilbara WA, there is an increase site for the Sun, on a riverbed: actions to stop the Sun shining at a specific place, and others to make the Sun shine brightly, are documented (Juluwarlu Aboriginal Corporation 2008)Footnote b . Where the Sun doesn’t shine, fish are attracted by localised shade, so are available to catch; and bright sunshine lowers the water level in the river which assists fishing. As Kelly (Reference Kelly2016: 4) observes, increase rituals are not merely superstitious acts aimed at increasing the fortune of a hunt: ‘Many of the songs reinforce details of animal behaviour … so, exactly as claimed, enhance the likely success of a hunt.’

Hamacher et al. (Reference Hamacher, Fuller, Leaman and Bosun2020) investigated if and how Australian indigenous peoples noted and used solar positions for signalling seasons or for other purposes. No reference is made to WA. Some historic stone arrangements appear to point to sunrise and sunset points at solstices and equinoxes, but none have been confirmed for WA (see Section 10, Stone arrangements). However, Noongar people knew that the Sun does not rise in the same place each day: the vocabulary by Moore (Reference Moore1842) includes kakur, meaning east, and ‘Kangal-The east; or, more properly, the spot of sun-rising, as it varies throughout the year.’ (ibid: 55). A search did not uncover if or how this knowledge was used. Also, about the Sun’s trajectory, the Kukatja people, south-east Kimberley consider the Sun: ‘… to be close to the earth at dawn and further away at sunset.’ (Peile Reference Peile and Bindon1997 in Clarke Reference Clarke2015: 30).

3.2. The Moon

Many Aboriginal Dreaming narratives identify the Moon ‘… with a man, sent to the sky for evil acts.’ (Norris Reference Norris2016: 8). This statement is certainly true for WA. An entry for Moon in Moore’s (Reference Moore1842: 52) Noongar vocabulary states: ‘Miak… the moon … The moon is a male, and the sun a female …’; and Moon-man/ evil-act links are evident in several WA accounts. For Lunga people, east Kimberley, ‘Moon is a man who broke incest (kinship) laws causing death.’ (Kaberry Reference Kaberry1939, in Johnson Reference Johnson2014: 195). Renowned artists Rusty Peters (b. 1935) and Mabel Juli (b. 1931), Gija people, east Kimberley, have painted the same topic with small variations. For example: Theliny Theliny-Warriny, Two Mothers for the Moon 2012, by Peters (Desert River Sea 2021a); and Garnkeny Ngarranggarni 2010, by Juli (Desert River Sea 2021b): the man in the narratives for these paintings wanted to marry the mother of the woman he was supposed to marry and became the Moon. Each month he dies (wanes) then comes back to life (waxes). Jaru Elder Jack Jugarie (b. 1927), east Kimberley, told the narrative of the Moon wanting to marry his cousin sister, who was inappropriate for him (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith2014). An old woman tried to redirect his interest, but the marriage took place. No consequences are mentioned – Goldsmith suggests the narrative may not be complete. Johnson (Reference Johnson2014) states also that wrong marriage is central to a Jaru narrative about the Moon.

For desert peoples of WA (Warburton Ranges groups, Kaili from the Western Desert and Yulbara near Laverton), Moon-man chases a group of women, wanting to have sex with them (Róheim Reference Róheim1945). Two ancestral men (Wati Kutjara) wound Moon-man with their magic boomerang, and he dies or otherwise meets his demise. Warburton Ranges groups and Kaili refer to marriage law as Kidilli law. Kidilli (Moon-man) should not have been chasing the women. He should have been marrying someone according to the law.

For the Mowanjum community in the west Kimberley, dark patches on the Moon appeared when a whirlwind carried away a disobedient girl and put her into the Moon; and having stared at the Moon (a taboo), two boys became glued together (Utemorrah et al. Reference Utemorrah, Umbagai, Algarra, Wungunyet and Mowaljarlai1980, in Johnson Reference Johnson2014). Barbara Merritt (b. 1950s), of Badimia people in the Murchison, recalled as a child being told: ‘Don’t do this, he’ll be watching you, there like, someone on the moon was something scary to look at … ’ (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith2014: 177). The messages in these narratives, as for the incest narratives above, are about social behaviour.

Aboriginal narratives, including some of the above, identify the waxing and waning of the Moon with living and dying. Norris (Reference Norris2016) provides the example that for Yolngu people, Northern Territory, the Moon cursed the world and said he would be the only one who could come back to life after dying. Hassell (Reference Hasselln.d.: 281) wrote of the Wheelman Noongar people, south-east coast WA: ‘The moon they say is different for he dies and comes to life, also he gets very fat and thin just before he dies.’ Hassell also recorded a Kangaroo and Moon story told by Moobbil, an elderly Aboriginal man. The friends of a boastful kangaroo started avoiding him, so he made friends with the Moon. The Moon also tired of his boasting and eventually bragged:

‘I never die, I live for ever’. There upon the kangaroo said ‘That is foolish talk’ he knew better than that, everything died. The moon declared it was quite true that he [the moon] never died, the kangaroo said things would change now, the moon should die for a short time then come to life again and it has been so ever since. (Hassell, Reference Hasselln.d.: 588–589).

Palmer (Reference Palmer2016: 197) refers to Moobbil’s story in his anthropological report for a Native Title claim saying a story:

… from the Jerramungup area, and relating to a particular site, tells of an interchange between the Kangaroo and Moon, both now being represented in the features of a large granite dome.

Hassell lived in the Jerramungup area, near the south coast of WA. Noongar Professor Kim Scott (b. 1957), Curtin University, also writes of the Kangaroo and Moon (Scott, Reference Scottn.d.: 15). The setting is potentially the large granite dome identified by Palmer (Reference Palmer2016):

I told Clancy of how Kayang [auntie] Hazel made us stop the car at the edge of the bitumen road … she crossed the wire fence and led us across the shifting soil to a rocky outcrop. She pointed, there: a series of neat circles in the rock that grew small, then larger again. ‘Yongar and Miak’, she said, and told the old story of Kangaroo and Moon [very similar to Hassell’s account] … It is both a responsibility and a privilege to stand beside where that story is imprinted in stone, and hear its ancient utterance.

Bates (Reference Batesn.d. b: 4) recorded a Kangaroo and Moon narrative from south-western WA:

In the Nyitting times of long ago, Meeka the Moon and Yonggar the kangaroo were friends, and used to sit down together and talk about things… One day they talked about death, and Meeka said to Yonggar, ‘What happens when you die?’

Yonggar wanted to hear first what happened to Meeka when he died, but Meeka tricked Yonggar into speaking first:

When I die I go murra murran (nowhere, anywhere) and my bones get white on the ground, and jellup the grass grows over them and covers them up.

Then Meeka the Moon laughed big and loud and said very quickly, … I die, I die, I sit up again, I die, I die, I sit up again, I die and come alive again and go home to Barramurning, my own country. Now if Yonggar had not spoken first and had made Meeka tell him what he did when he died, all the Bibbulmun people would have been able to come up again after they died, the same as Meeka the Moon.

Hence, while the Sun is often linked with creation in WA Aboriginal narratives, the Moon is often linked with social behaviour. Another example from the Wongry [Wongai people, Eastern Goldfields?], is a man, Kalu, who was terrified of the night, consequently became pale and round and obsessed by his problem, turned into the Moon, and sometimes rests on a boomerang (Noonuccal Reference Noonuccal1990, in Johnson Reference Johnson2014).

The single account that I found from WA which refers to Moon as female relates to Dale’s Cave, located northeast of Perth on a bank of the Avon River. Armstrong (Reference Armstrong1836: 790), an early settler, wrote that Perth Aboriginal people call the cave: ‘… ‘Mountain of the Moon,’ because they believe that the Moon once entered that cavern, and left the print of her hand on its side.’ Moore (Reference Moore1842) describes the same cave but does not refer to Moon as being male or female. Another version of the narrative is that:

Legend has it that in the Dreamtime the moon was a man on the earth and some warriors chased him into this cave. He got tired of being confined there so he put his hand on the cave wall and using that leverage he burst out, making the jagged hole in the roof and escaped into the sky where he roams around still. (Shire of York, n.d.: 4).

Other Moon narratives from WA are as follows. From the south-west (Bates, Reference Batesn.d. b: 20):

Kagabin, near Mt. Stirling, is full of spirit babies (kagub) and any woman who goes there and looks at Kagabin will get a baby. Miuk (the moon) is also the baby giver, and when he is full you can see all the babies. He is the maam (father) of all nungar (men) for it is he who gives the babies to their women.

Another narrative relates to the cave Meekadarabee (the bathing place of the Moon), Noongar Country. A girl drowned herself in the cave after her lover was killed. When the Moon is bright, you can see her hair reflected in the water (South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council, Reference South West Aboriginal and Sean.d.). Joe Northover, of Wheelman Noongar heritage, describes Minningup, a stretch of the Collie River, south-west WA (Northover, Reference Northovern.d.: audio):

It is the resting place of the Ngangungudditj walgu, the hairy faced snake. Baalap ngany noyt is our spirit and this is where he rests. You have big bearded full moon at night time you can see him, his spirit there, his beard resting in the water. And we come to this place … to show respect to him.

Based on Akerman’s (Reference Akerman2016) extensive account of Wanjina mythology from the north Kimberley, the Milky Way is the home of sky heroes (see Section 4.3), but there is little mention of the Sun, Moon and other objects in the sky. However, the mythical Black-headed Python, a key figure, is married to the Moon, Karnki.

A creation narrative for Lake Coogee in Perth, related by an Aboriginal consultant during a land survey (McDonald et al. 1997), tells of a sparrow and a hawk that flew to a round hole in the earth, where the Moon rested during the day. The two birds stole fire from the Moon in the form of a firestick. They flew along the limestone ridge near the ocean. The bush caught fire. The Moon called his uncle, the ocean, to help. The ocean rose and extinguished the fire. Nyungar people were drowned, and the lakes in the area were formed, including Lake Coogee.

Nora Nungabar (c. 1919–2016) of the Martu people, east Pilbara, was born and grew up in country that became Wells 33–38 of the Canning Stock Route (Martumili Artists Reference Martumili2021b). Norah’s painting, Kinyu n.d., depicts Kinyu (Well 35, Canning Stock Route). The statement for the painting (Estrangin Gallery Reference Estrangin2021b) describes the Dingo Dreaming for the area in which two dingoes travel to Wilarra, ‘… following the call of the moon.’ Wilarra is on the edge of a lake and the name means Moon. The dingoes and their litter of puppies are looked after by the Moon, and later travel east towards the rising Moon, to Kinyu. A fuller version of the narrative can be read on the Estrangin web page for the painting. The Dreaming is also illustrated in the collaborative painting Wilarra (Martumili Artists Reference Martumili2017), which references a windbreak that was created by the Moon as shelter for the dingoes.

As well as being the subject of narratives, the Moon is recognised as a weather indicator by Aboriginal people. Norris (Reference Norris2016: 9) explains that: ‘In cold weather, a halo often surrounds the Moon, as a result of ice crystals in the upper atmosphere.’ A halo was linked with cold weather by Ngadju people, Eastern Goldfields, WA: ‘A big circle around the moon indicates rain and cold temperatures.’ (O’Connor & Prober Reference O’Connor and Prober2010: 22).

In the statement for his painting Dry Season, 2013, Rusty Peters, east Kimberley, addresses weather prediction: ‘It’s getting dry, big dry season. You know it’s going to be hot when the stars are all [gestures twinkling movement] and the moon, so bright.’ (Desert River Sea 2021c). From a scientific viewpoint, twinkling blue stars can indicate hot weather, but twinkling and weather are not strongly correlated (Hamacher et al Reference Hamacher, Barsa, Passi and Tapim2019); and the Moon does not affect temperature on Earth (Hogg Reference Hogg1935).

The Moon also serves as a calendar for ritual and ceremony. Norris (Reference Norris2016) gives the example from Tindale (Reference Tindale1983) that, for the Kaiadilt people, Bentinck Island, Queensland, the first appearance of a new Moon in the west triggered a ceremony in which the moon is asked to help with the weather, food supplies, or an especially low tide. In South Australia, a colonist noted that Aboriginal people lit fires in the hills at every new moon (Clarke Reference Clarke1997). A song and details of an increase ceremony for a bright moon, to assist hunting at night, and the location of the ceremonial site, are documented for Yindjibarndi peoples in the Pilbara, WA (Juluwarlu Aboriginal Corporation 2008). The Meeka Moorart Full Moon celebration in Perth in 2019 and 2020, saw the performance of Meeka Moorart, a song composed collaboratively for the celebration (Walley Reference Walley2020). Dr Richard Walley OAM (b. 1953) is a prominent Noongar musician, artist and campaigner for his people and culture. The song relates to Whadjuk Noongar people. Speaking of the song, Noongar Elder Noel Nannup (Reference Nannup2020) said:

The vision for the … [Moolarong ?] Meeka, which is the song for Meeka Moorat, the Moon is rising, and as it’s rising, of course that’s a very important time of the day, and as it first peeps over the horizon, that’s been seen by thousands of generations of our people, and at that instant, it is like you are just continuing an ancient ceremony of singing a song that is attached to ancestry …

Ceremonies may be for males or females only, or mixed: for the Wolmeri people of the Kimberley, ritual and ceremony linked with the Moon were witnessed by men only (Kaberry Reference Kaberry1939, in Johnson Reference Johnson2014).

In summary, Aboriginal narratives from WA about the Moon generally reference socially unacceptable behaviour (incest, boasting, speaking first, disobedience), and banishment to the Moon – something to fear. Moon is almost always cast as male. Further, the narratives link sometimes fantastical happenings on earth with phenomena associated with the moon: the waxing and waning, reflection on water, shining briefly in a cave, dark patches, crescent shape (boomerang), yellow moon not being visible during the day, and rising in the east. Using words of Natale (Reference Natale2012), the narratives describe situations that encapsulate in miniature the characteristics of something much larger – Moon in the night sky. In addition, Moon was used as a weather indicator, a marker of time (see Section 8.2), a calendar for events, and was a focus of ritual.

3.3. Solar eclipses

Traditionally, for Aboriginal people, a solar eclipse: ‘… was an omen of impending disaster, or a sign that someone was working black magic.’ (Norris Reference Norris2016: 10). Further, Hamacher and Norris (Reference Hamacher and Norris2011a: 106) note that solar eclipses ‘… caused reactions of fear and anxiety to many.’, and they provide the following examples for WA. Mandjindja people from the Western Desert, said they had seen a solar eclipse once only and that they were struck with fear, but were relieved when the eclipse passed and no-one was harmed (Tindale 2005). Pitjantjatjara people of the Central Desert, partly in WA, believed that bad spirits made the Sun dirty during a solar eclipse (Rose Reference Rose1957). The Yircla Meening of Eucla, Eastern Goldfields, believed solar eclipses were caused by: ‘… the Meenings of the moon, who were sick, and in a bad frame of mind towards those of Yircla [the Morning Star, Venus].’ (Curr Reference Curr1886: 400). The people of Roebuck Bay, west Kimberley, were others who became fearful (Peggs Reference Peggs1903).

Jaru Elder Jack Jugarie, east Kimberley, recalled in 1999 that, after World War II, the Sun had got dark, ‘… not really dark, just like a shade … stopped for a while … sun moving … bright again …, and make you warm again.’ (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith2014: 138). The description fits a partial eclipse, perhaps the one in December 1954 (ibid). Goldsmith doesn’t report whether or not Jack indicated fear.

Explanations for the cause of solar eclipses vary, but many groups seemed to understand that they occur when the Sun is covered by something (Hamacher & Norris Reference Hamacher and Norris2011a). In south-west WA, some groups believed a solar eclipse was caused by sorcerers placing their booka (cloaks) over the Sun, while others believed sorcerers moved hills and mountains to cover the Sun (Bates Reference Bates and White1985). People of the Central Desert WA held that a solar eclipse was made by a man covering the Sun with his hand or body (Bates Reference Bates1904–1912a, in Hamacher & Norris Reference Hamacher and Norris2011a).

Hassell (Reference Hasselln.d.: 146–147) relates a covering the Sun explanation of a solar eclipse, from Wheelman Noongar people, south-east coast WA. In summary: Long ago, the Zhi (Sun) shone all day, and all night the Maak (Moon) was bright. The men hunted in the daytime, but then they went to sleep and did not hunt, and the women scolded them. There was a big noise, and the Zhi and Maark came down and split the earth in half. The men that slept and the women that scolded were on one side. Those who had hunted remained on the other side. It is never cold, because the Zhi shines all day and the Maak all night. But now and then the Nunghars on the other side of the Sun want to know what is going on here, so they crowd together and they tip the Sun over one side as they peer down. There are a lot of them so they cover the Zhi and make it dark, then it is very cold down here. They take the warmth away for themselves. But they don’t stay long, they only stop long enough for each one to look down. Thus, notably, the narrative incorporates the lowering of temperature during a solar eclipse.

3.4. Lunar eclipses

On the visual appearance of a lunar eclipse, a narrative from Eucla, Eastern Goldfields WA, describes a man ascending to the Milky Way who can only be seen when he ‘… walks across the moon …’ (Róheim Reference Róheim1971: 53). Hamacher and Norris (Reference Hamacher and Norris2011a) note that the red colour of the moon is sometimes linked with blood and provide a WA example from Elkin (Reference Elkin1977): for Ungarinyin people of the Kimberley, an unfriendly medicine man causes the moon to be covered with blood and this frightens everyone: but a friendly medicine man ascends into the sky and, when he returns, tells everyone he made the moon better.

In summary of Sections 3.3 and 3.4, as is the case for the Sun and Moon, WA Aboriginal narratives about eclipses draw on everyday experiences. Being fearful of eclipses is correlated with fear of people being sick, in a bad frame of mind, bloodied, dying. A dark patch appearing is correlated with light being blacked out with a cloak or hand, the shadow of a man walking or a person or crowd being a barrier to seeing something. The solar eclipse narrative recorded by Hassell (Reference Hasselln.d.) weaves in the lowering of temperature during a solar eclipse. Eclipses are sometimes attributed to spirits being at work.

3.5. Relationship between earth and sky

In many accounts:

Earth and sky are two parallel worlds which mirror each other, and the sky … is a reflection of the terrestrial landscape, with plant and animals living in both places … Clever men are said to be able to move between land-world and sky-world … The sky is often regarded as being relatively close to Earth … Many groups believed that all celestial bodies were formerly living on Earth, partly as animals, partly as men, and that they moved from Earth to sky. (Norris Reference Norris2016: 11).

For Karadjari people, Pilbara WA, the powerful rainbow serpent was a rainbow by day and a celestial river by night (Worms & Petri Reference Worms and Petri1998, in Clarke Reference Clarke2014). For Aboriginal peoples of the north Kimberley, the Skyworld was populated with a Lord, and lesser spirits (Wanjina) who came down to earth to create the people on earth (Akerman Reference Akerman2016). For Noongar people, south-west WA, stars were campfires of the ancestors (Winmar Reference Winmar2009), and are also described as campfires of tribes (Hassell, Reference Hasselln.d.: 285).

In the Two Sisters Dreaming told by Paddy Roe (1912–2001), Elder of the Goolarabooloo tribe of the Nyigina, of the Kimberley, one sister found some Njarri Jaari (bush onion), but was greedy and made a snake from bark to frighten her sister away (in Hoogland, n.d.). But when the sister ran up and saw the snake, ‘she sang out “sister, big snake, cannot come to you!” At that moment, the two sisters and the snake went up into the sky.’ They can be seen as stars, one each side of the Milky Way, when the Njarri Jaari is found.

Johnson (Reference Johnson2014) identified another theme that the skyworld shape is a dome, which comes down to the horizon, and is sometimes conceived as hard. For the Karadjeri people of the north Pilbara/south-west Kimberley, the dome was made of rock or shell (Piddington Reference Piddington1932, in Johnson Reference Johnson2014). Another insight into Aboriginal people’s conception of the skyworld is provided by Goldsmith (Reference Goldsmith2014: 184). When mentioning deep space to Kevin Merritt (b. 1943), of the Wajarri people in the Murchison WA, Kevin responded: ‘And you say deep space. We don’t have that … we don’t see deep space. As Aboriginal people, we just see what is around us, what’s above us.’

The epic creation Dreaming, Moondang-ak Kaaradjiny: the Carers of Everything, told by Noongar Elder Noel Nannup (Nannup Reference Nannup and Mia2008), has the elements described by Norris (Reference Norris2016), except for clever men. In summary, spirits moved across the land during the nyetting (cold time), realised they were going to become real and wanted one group (people, plants or animals) to become carers of everything. A spirit serpent, the Wogarl, used all its strength to partially lift the sky, became real, created trails and hills, went underground and rose again where there would be lakes. The sky was lifted up from Earth, by spirit children working in unison; the Milky Way was created by a spirit woman who carried spirit children up in her hair; shooting stars are spirit children returning to Earth; spirits on Earth became real with the first hint of wind.

Others tell the same Dreaming or elements of it including Noongar Elder Toogarr Morrison (b. 1950) in Goldsmith (Reference Goldsmith2014), and the narrative is on a plaque in Victoria Park, Claisebrook, East Perth. Robertson et al. (Reference Robertson, Stasiuk, Nannup and Hopper2016) link components of the narrative with events that are believed scientifically to have happened over millennia, focusing on the Permian ice ages, 350 million years ago, through to the Holocene flood, 7 000 yr ago. The purpose was not to prove the narrative is true, but to seek synergies of meaning between cultures.

An account by Hassell (Reference Hasselln.d.) touches on an earth/sky relationship for the Wheelman Noongar people. She asked Tupin, an Aboriginal girl who knew a lot of Native law, with Tupin’s friend alongside:

‘Is the earth round like this ball (holding up a ball of crochet cotton) or square like the box I am sitting on?’ ‘Round like a ball’ both the girls promptly replied. ‘How do you know?’ I asked. Both the girls promptly replied ‘Oh Missus just look all round yer’. See the sky touching the earth all round. Wherever you stand and look it is all round put baby down to walk he soon run round, not always straight along fence, see ship get lost they run round, say um Yonga [kangaroo] run straight very little, then run round and Missus white man know it … (Hassell, Reference Hasselln.d.: 187).

Extracts of the above are sometimes quoted as evidence that, traditionally, Wheelman people believed that the earth is finite and/or round, a conclusion that the latter part of the quote possibly casts in doubt.

The painting Sunrise Chasing Away the Night 1977–78, by Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri (c. 1926–1998), Western Desert WA (National Gallery of Australia 2021) provides a topographical view, looking from beyond the Sun down onto Earth, with stars between Sun and Earth, and a ceremonial ground, stones and campfires. The title of the painting implies a moving Sun – a view that is implied by language worldwide.

Places of the dead are also relevant to the Earth – Sky relationship. Johnson (Reference Johnson2014: 30) identifies that, for some Aboriginal peoples : ‘… there was a specially designated earthly place of sojourn for the dead, always located well away from that of the living.’ WA examples provided by Johnson are that: for Kimberley people, the place of the dead was in the west (Kaberry Reference Kaberry1939), or in the Milky Way (Durack Reference Durack1969); and that over Australia generally, particularly in the west and north-west, spirits of the dead went to the sky-world and lived with the ancestral heroes (Berndt & Berndt Reference Berndt and Berndt1974).

For Aboriginal people in Broome (west Kimberley), the place of the dead was ‘… Loomum … beyond the great sea that beats the country that is now Broome.’ (Bates, Reference Batesn.d. c: 44). For Walanwonga people in the Murchison, the dead go to ‘… a big hill far away … but they hover for some time over their own districts before they go … ’ (Bates, n.d. d: 1).

For Noongar people: ‘Their general belief is that the spirits of the dead go westward over the sea to the island of souls, which they connect with the home of their fathers.’ (Moore Reference Moore1842: 83). For Wheelman Noongar people, south-east coast WA (Hassell, Reference Hasselln.d.: 281):

The sun is the far off land where the natives go and live after they die, no evil spirit can get there, and it is wonderful fertile country. When I [Hassell] remarked that it must be very hot I was told it is not so, the heat came from the sky which was below the sun and had nothing to do with it. The sun was above everything, the stars, moon and heavens, and independent of them all. It was the abode of the departed.

In a native title submission to the Federal Court (Palmer Reference Palmer2016: 136), Noongar informant Lynette Knapp (south coast) stated that her father had taught her that the spirit of a dead person went ‘… beyond the sun.’

There are various narratives about how movement between earth-world and sky-world occurred, including via tall trees (Clarke Reference Clarke2015), a rainbow, a string and a hair cord (Johnson Reference Johnson2014). In the north Kimberley, it was via a rainbow, and in the east Kimberley, via a string (Elkin Reference Elkin1945, in Johnson). The Seven Sisters of the Pleiades escaped WA as birds (Mountford Reference Mountford1976, in Haynes Reference Haynes2000; Walley Reference Walley2013), were blown into the sky on a baark (cloak) (Hassell, Reference Hasselln.d.), or simply flew there (FORM 2019). The Four Sisters of the Southern Cross were blown from earth into the sky (Hassell, Reference Hasselln.d.). Emu in the Sky was blown from earth to sky in smoke from a fire, and Moon was passed through enroute (ibid), see Section 4.7. Moon is also cast as being enroute to the heavens in a lunar-eclipse explanation given above (Section 3.4).

For Noongar people, spirits of the dead journeyed under father sea, west of the land of the dead (Bates Reference Bates and Bridge1992). Joe Northover (n.d., audio) of Wheelman Noongar heritage says of a stretch of the Collie River, south west WA:

And we come to this place here today to show respect to him [Ngangungudditj walgu, the creator serpent] plus also to meet our people because when they pass away this is where we come to talk to them… This is where all our spirits will end up here… And we come and look there and talk to you old fellow [walgu]… Your people come to rest with you now.

Phillip Chauncy, the Western Australian Government Assistant Surveyor from 1841 to 1853, wrote:

Before the arrival of a ship from Europe, the Swan River natives supposed that the spirits of the deceased passed into the cormorants which frequent the Mewstone, a granite rock some miles out in the sea opposite the mouth of the Swan River, called by them Gudu mitch, a compound of Gu-urt, the ‘heart’ and mit or mitch, the ‘medium’ or ‘agent’ – signifying that this island is the medium or agent by which the spirit of the departed one enters the body of a cormorant. Large flights of these birds used to pass up the estuary of the Swan every morning on fishing excursions and return to the Mewstone in the evening, and the natives refrained from killing them lest thereby they should be slaying their ancestors (Chauncey Reference Chauncy1878, in Macintyre & Dobson Reference Macintyre and Dobson2017b).

Noongar artist Rod Garlett (b. 1962) paints: ‘stories based on significant sites of his ancestors, and ancestral beings. He places tremendous importance on the fact that he lives and works in his ancestral Avon, Swan and Canning River country.’ (Vivian Reference Vivian2014). In describing his painting Noongar Boodja Wangkiny (Our Land Is Talking) (Garlett Reference Garlett2017: video), Rod points to a Western Australian Christmas tree, nuytsia floribunda, Noongar name moodjar, saying:

It was a tree where our family, when they passed on, their spirits would rest there first, at that tree, and they would rest there before they went on to a place that the old people called Caranup, which is Aboriginal heaven, beyond the sea.

Noongar Elder Marie Taylor (b. 1948) also identifies a tree species as an intermediary place for spirits of the dead:

One of the best trees in this area around here Djalgarro River (Bull Creek) is the sheoak tree, kweli, that sings and cries. And when it is crying it is telling us that the spirit of the babies is sitting in the trees. And they are waiting to go down to Caranup, where the river meets the sky. (Taylor Reference Taylor2017: audio).

Aboriginal people continue to treat moodjar and kweli as sacred to this day, for example, by not breaking branches (Garlett Reference Garlett2017; Taylor Reference Taylor2017).

In summary, the narratives on the relationship between earth and sky, and after life, are generally in terms of phenomena, objects or actions that are observable on or from earth. The skyworld is a dome, resting on the ground around the horizon. The apparent separation of earth and sky was achieved by lifting. A rainbow or a string allowed access between earth and sky, or earthly beings simply went as birds, were blown into the sky, or were spirited under or in water (sea or river), with transition or resting places in a river with the creator serpent, in birds, or on trees. The abode of spirits of the dead is the sky generally, the Milky Way, the Sun or beyond it, at locations to the west (where the sun sets over the ocean), or a big hill far away.

4. Stars, constellations and galaxies

Aboriginal peoples have narratives for individual stars, constellations and dark spaces between stars (Norris Reference Norris2016). As in the Dawes Review (ibid), constellations and dark spaces only are considered in this review. I found few single star accounts from WA, and stars in those are sometimes assigned Aboriginal names, but not European names, which made identification for this review impossible.

4.1. Orion

In many Aboriginal narratives, Orion is a hunter, a man or a group of men, or is linked with male initiation ceremonies (Leaman & Hamacher Reference Leaman and Hamacher2014). If cast as a man, Orion is often associated with the Pleiades (Seven Sisters) and is frequently chasing them, including in narratives from WA, see Section 4.2 below.

Orion (known as Nyeeruna) featured in male initiation ceremonies observed at Ooldea and near Oodnadatta, South Australia (Leaman & Hamacher Reference Leaman and Hamacher2014). Each ceremony was witnessed and described by Berndt and Berndt (Reference Berndt and Berndt1943, Reference Berndt and Berndt1945) and was repeated many times over a week. It was as though Orion chased the Seven Sisters, then was dismembered by a dingo. Subincision of new initiates occurred at the end of the week. The week was timed so that Orion was in the daytime sky, and not visible at night, or at sunrise or sunset (Bates Reference Bates1904–1912b, in Leaman & Hamacher Reference Leaman and Hamacher2014). In other words, the movement of Orion served as a calendar. Another calendar example from Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, is that Orion rising at dawn (about June) signals the coming of dingo pups (Elkin Reference Elkin1974, in Johnson Reference Johnson2014).

For the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara peoples of the Western Desert, partly in WA: ‘Wati Nyiru is the ancestral man who pursued the sisters across land and sky.’ (James 2015: 42), informant Nganyinytja (c. 1920), a Pitjantjatjara Elder woman, OAM). On earth he was:

… an older clever man, a shape-shifter of great powers who can turn himself into ripe bush tomatoes, great big shade trees, grass seeds ready for gathering – anything to entice the young maidens into his grasp.

In the sky: ‘… he is the red star that most of us know as Taurus and his footprint is Orion’s belt.’ (ibid). His misshapen footprint, Orion’s belt, follows the sisters forever.

Jaru Elder Jack Jugarie, east Kimberley, also associated the Orion constellation with a lizard footprint. He:

… referred to the stars which make up the belt and ‘sword’ of the constellation Orion … as ‘Kalarrcar’, the lizard footprint… Jack drew both the imprint of the lizard footprint, and the star pattern, noting the similarity between the two. (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith2014: 142).

No narratives about lizard were reported.

A narrative with a message about social behaviour and the preservation of species, from the Ngaiuwonga tribe in northwestern WA (Bates (n.d. d: 3), is as follows:

Ngadagurdain, a Ngadawonga, stated that biargo (black cockatoo, red tail) was yamaji, Miamba time [long long ago]. A warura or bogar [turtle?] laid some eggs and covered them up. Biargo wandi (women) were away in the bush, but presently came back and saw the eggs. They sat around them and lifted the cover up and then all the eggs fell down and broke. The women fell down too and they are now up in the sky. They turned into biargo and went up bila (skywards) but some remained down on earth and that is why there are biargo. The biargo who went up bila, now form the constellation Orion.

4.2. Pleiades

Norris (Reference Norris2016) identifies that, for nearly all Australian cultures, the Pleiades are female, often sisters or a group of young girls, chased by young men, usually in Orion; and that the number seven is puzzling because less than seven bright stars are normally visible in the cluster; but, in several accounts some of the sisters are absent. Narratives from WA mostly fit these descriptions.

Three major art projects which involved Elder women painting, dancing, singing and telling their Seven Sisters narratives have been completed. One relates to the Canning Stock Route, WA (La Fontaine & Carty Reference La Fontaine and Carty2011), see Figure 1; another to Martu Country which includes places on the Stock Route (Coates & Sullivan Reference Coates and Sullivan2012), the third to the Martu Country including part of the Canning Stock Route, and Anangu/Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytatjara (APY) Lands (partly in WA, mainly in Northern Territory and South Australia), and Ngaanyatajja Lands (mostly in WA) (Neale Reference Neale2017), see Figure 1. In addition, Macfarlane and McConnell (Reference Macfarlane and McConnell2017) bring together Seven Sisters narratives for the Canning Stock Route. In brief, the Seven Sisters are chased by a man (Orion) known by different names by different language groups, who wants to have sex with them. The Sisters fly from place to place, create water sources and other landmarks, and, at various locations, they rest, dance, sing, pierce their noses, get lost or sick, hide, get caught by the man/men, defend themselves, suffer rape, escape, split up, regroup and fly away into the sky.

Noongar Elder Noel Nannup (Nannup Reference Nannup and Mia2008: 98) relates:

When it comes to the story of the Seven, there are really only six, as the seventh is one of the planets, and the planets go the opposite way. This is why you will always hear the desert people saying the seventh sister is coming home … You will see the seventh sister getting closer and closer, but then she will go past … And when that happens, people will say she has visited her sisters.

Six sisters in the sky was also implied by Wongai Elder Josie Boyle, Eastern Goldfields WA, when speaking about her mother:

… my mother was a star girl. We called her a star girl. But she always believed she was one of the Seven Sisters left behind. We had to watch her [dance] every day, and become that star sister. And she said that star sister, Seven Sisters, left behind, and she was in that story… So we couldn’t go past that story every day. (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith2014: 515).

Josie carried into a story for children (Boyle Reference Boyle2007) some of what she learnt about the Seven Sisters from her mother, see Section 3.1. The end of that story, in which Jindoo-the Sun, sent seven sisters, stars of the Milky Way, to beautify the earth, is that they needed water and the youngest sister was sent for it. Two spirit men found her, and she fell in love with them, which was forbidden. After finding her, the other six Sisters returned to the Milky Way, leaving the youngest sister behind.

Recognised educator May O’Brien MBE (b. 1932) of Wongai heritage, in her storybook (O’Brien Reference O’Brien2009), describes how Seven Sisters landed on a plateau on earth, were chased by small Yaryarr men most of whom gave up, but one persisted and approached a sister who had wandered away from the group. She ran for her life back to the plateau, realised that her six sisters weren’t there, saw them in the sky and followed them. So, today six sisters can be seen clearly, and the seventh faintly, as she trails behind.

For the Pitjantjatjara people, Central Desert, partly in WA, the Seven Sisters kept a pack of dingoes for protection but, despite that, a man raped one of the sisters who then died (Mountford Reference Mountford1976, in Haynes Reference Haynes2000). The man pursued the other six who became birds and flew into the sky. He followed them and is seen in the stars of Orion’s belt. Noongar Elder Theresa Walley (b. 1937) links the sisters with birds in her Seven Sisters storybook (Walley Reference Walley2013). They have the names of birds and are sent to search for their father. They venture too far, lie down to rest and never awake. Their spirits drift into the heavens and can be seen in the night sky. They return as beautiful birds during the day. Johnson (Reference Johnson2014) observes that casting the Seven Sisters as earthly birds is common for Aboriginal people in general. Perhaps because the Seven Sisters, like birds, are free spirits?

As in the Pitjantjatjara Seven Sisters narrative, dingoes for protection were a component of a Seven Sisters ceremony that White (Reference White1975, in Johnson Reference Johnson2014) witnessed in desert areas, from west of Warburton (WA) into South Australia. The ceremony was for a girl’s first menstruation. A woman took the role of a man, representing Orion (Njuru), who chased seven women from the north-west. He chased them through WA (Meekatharra, Wiluna, Laverton, Kalgoorlie to Cundeelee), where he caught one, raped her and she subsequently died – a consequence of the man being a relative so that the rape was beyond moral behaviour as well as marriage lore. The six sisters continued with the man in pursuit. The women set their dingoes upon him when he attempted rape again.

In the Wati Kutjara narratives for desert peoples in WA (some Warburton Ranges groups, and Kaili), see Section 3.2, the women who were chased by Kidilli (Moon-man) are identified as the Pleiades (Wonatara) (Róheim Reference Róheim1945). In the version recorded for Yulbara people near Laverton, the women went up to the sky after Kulu (Moon-man) was killed and they became the Pleiades. In the Pilbara (Tararu and Ibarga groups), the two heros:

… rescued the Wonatara women [the Pleiades] from two mythical serpents (Wonambi) and then they went into the sky and waited until the Wadi Kudjara should come up and marry them. (ibid: 43).

Two other very different narratives are told about the Seven Sisters. For the Goolarabooloo people of the Dampier Peninsular, west Kimberley: Marala the Emu Man (Emu in the sky) chased Ngadjayi, spirit women from the sea (Salisbury et al. Reference Salisbury2016). The spirit women failed to listen to a command of their leader, Yinara, who then shamed them, and together they moved into the sky and became the Pleiades. Natural stone pillars at Bungurunan Beach, south of Broome, now represent the Ngadjayi.

Hassell (Reference Hasselln.d.: 287–294) recorded a narrative of the Wheelman Noongar people (south-east coast WA). In summary, a man goes hunting and meets three Kar Kar (men from another tribe). The man asks them to his camp with his wife, children and Wardah, who is to be the wife of the eldest son. They all travel to the coast. A Kar Kar wants Wardah as his wife so the Kar Kar are told to leave. The Kar Kar attack, the man and sons are speared, a wind blows them into the sky. Orion is the man with a son on each side, and the three stars hanging down are the Kar Kar trying to reach them, which is a warning to all not to take in strangers. The wife, children and Wardah hide, and a baark (cloak) is spread over the children. A storm blows up, wind catches a corner of the baark and blows them all into the sky: the wife and Wardah are the two brightest stars in the Pleiades, the dimmer ones are the children because the baark covers them. Notably, the men chasing the Seven Sisters become stars of Orion, which is a variation from the chaser being the star constellation.

The names of many locations visited by the Seven Sisters are known publicly, particularly along the Seven Sisters Songline which starts in Roebourne on the northwest coast of WA, crosses the Pilbara, goes north-east up part of the Canning Stock Route, south-east through the Western Desert, crosses into South Australia, and finishes near Coober Pedy (Macfarlane & McConnell Reference Macfarlane and McConnell2017). The rugged terrain traversed in WA is highlighted in the video Minyipuru: Waters of the Songline (Martumili Artists and the Australian National University 2016).

However, any route, such has just been described, is a simplification for:

The Seven Sisters Songline is not a single line, but is a woven set of lines that come together and disperse, and that have numerous additional lines spreading out from them. (Macfarlane & McConnell Reference Macfarlane and McConnell2017: 66).

Further, in their National Heritage assessment, Macfarlane and McConnell (Reference Macfarlane and McConnell2017: 70) put forward the view that: ‘Because the route was flown, it is unlikely that the route has significance as a physical place.’ The places visited hold significance, and many are water sources – which were created by the sisters and which were important for Aboriginal people when traversing the songline (ibid). These include Wantili waterhole, Juntujuntu, a permanent spring, Mujingarra, a permanent large pool, all on the Canning Stock Route – in fact the Stock Route was planned along the songline and Aboriginal people were forced to reveal the water sources, which sometimes resulted in depletion and put Aboriginal people’s lives in jeopardy (ibid). Some stopping places for the Seven Sisters offered particular bush foods including bush melon and bush onion (FORM 2017). Ceremonial and resting sites have also been documented (e.g., Neale Reference Neale2017).

Noongar Elders identify Cantonment and Clontarf Hills in Fremantle with the Seven Sisters, and say five other hills in the area have been flattened, but that the spiritual essence of the landscape lives on (City of Fremantle et al. 2016). The five hills were quarried early on for the Fremantle Harbour development. Josie Boyle, Wongai Elder, described another Seven Sisters place in the mid-west of WA:

… in the back of Geraldton … where that road goes, … you go over that hill. You see all these beautiful formations of hills and things. Well along there, there is a lovely story of how they dropped the crystals through there. (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith2014: 523).

Josie also spoke of a Seven Sisters site in the Eastern Goldfields: a hill in Coolgardie that was a dancing site and end of the Sisters’ journey on Earth (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith2014). Noongar Elder Noel Nannup, referring to the Wongai people, wrote: ‘Their Seven Sisters Dreaming starts at a place called Weibo, north of Kalgoorlie in the Goldfields, at a very special place where the sisters came down from the sky.’ (Nannup Reference Nannup and Mia2008: 98).

Paddy Walker, Wongai Elder and law man, Eastern Goldfields (Brody Reference Brody2005), described how the Seven Sisters visited Lake Ballard (Figure 3): they stopped and played, and a man chased them. They hid in seven rock holes on the shore of the lake, became islands on the lake, the man seized the youngest of the girls and a young man loved one of the sisters and wished to dance with her. A tree at the end of Lake Ballard is one of the sisters. O’Brien (Reference O’Brien2009) names other Eastern Goldfields places which the Seven Sisters visited: a flat-topped plateau near Leonora; a hill near the plateau called Yabu Yulangu which means the hill where they cried; and places close to Wiluna, Laverton, Kalgoorlie and Menzies. Lake Ballard, in Paddy Walker’s account is near Menzies.

Figure 3. Lake Ballard, where the Seven Sisters became islands in the lake. Photograph by P. Forster.

Also in the Eastern Goldfields, Ngalia people hold that the Die Hardy Range including Mount Geraldine, is associated with and represents the man who pursues the Seven Sisters, and that peaks in the Yokradine hills represent the Sisters (Muir Reference Muir2012). ‘The name of the Yokradine Hills is based on the Noongar term Yokrakine, yoka kaany, women’s spirit place.’ (Muir Reference Muir2012: 17, source Tim McCabe). Muir (b. 1970) is leader of the Ngalia people. Tim McCabe is a long-standing Noongar Language Teacher, Ph.D. Curtin University.

Men performing the Balga traditional corroboree in the Kimberley carry totem boards which depict elements of the corroboree story. The dance style (Waringarri Arts Reference Waringarri2017: video) is traditional, but the story can be current: the story is passed through the generations via dreams; the current owner is Alan Griffiths (Carriageworks, n.d.). The totems were traditionally made with hair and are now made with thread. The thread constructions represent the Seven Sisters, the Morning Star and other non night-sky elements, as do the paintings by Alan Griffiths, for example Bali Bali Balga, 2012 (Desert River Sea 2021d). I haven’t uncovered the connection between the current story and the Seven Sisters and Morning Star.

In summary, Aboriginal narratives from WA, as for Australia in general, refer to the Pleiades as Seven Sisters. Sometimes one sister dies or is left on earth when the others return to the sky, leaving six. Six is consistent with what typically can be seen with the naked eye. One narrative casts the seventh sister as a planet. The (spirit) sisters descend from the sky or emerge from the sea, or start as women and children on earth. In two narratives, dingoes protect them. After their experiences on earth, which usually involve being chased by a man (Orion) or men (stars of Orion), the sisters return to the sky, sometimes as birds (free spirits). The narratives often convey a message of unacceptable behaviour, including wandering away, falling in love inappropriately or being the subject of lust. Landmarks including hills, ranges and islands, and all-important water sources, are associated with the sisters.

4.3. The Milky Way

The Milky Way is widely recognised across Australia. Narratives about it vary, including that it is a celestial river, a canoe, Rainbow Serpent(s), and that nebulae are camp-fires (Norris Reference Norris2016). Haynes (Reference Haynes1992) provides images of post-colonial paintings on bark by Aboriginal people that allow insights into many night sky narratives, including the canoe representation of the Milky Way. Another common view is that everything on earth is represented in the Milky Way, including ancestors, ancestral places, tribes and campsites (Johnson Reference Johnson2014). For example, the Kamilaroi people, New South Wales/Queensland, hold that the big river Warrambool in the sky (the Milky Way) mirrors the Big Warrambool floodway (Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Norris and Trudgett2014a). To the Ngaiawang of the mid Murray, South Australia, the Milky Way symbolised the Murray River (Tindale n.d., in Clarke Reference Clarke1997).

The Milky Way is also seen to represent moieties or skin groups (Norris Reference Norris2016). Norris provides the examples of Groote Eyland people, Northern Territory (Mountford Reference Mountford1956), and the Aranda and Luritja people, Central Australia, Northern Territory (Maegraith Reference Maegraith1932). For Walbiri people, Northern Territory, initiation ceremonies are associated with the ancestors’ cutting up of the Milky Way to form individual stars (Meggitt Reference Meggitt1966, in Johnson Reference Johnson2014). Dark patches in the Milky Way are also subjects of narratives. Aboriginal accounts from WA about the Milky Way are considered in this Section, while dark patches are considered in Section 4.7.

For Karadjari people of the Pilbara, Bulanj, the rainbow serpent, ‘… is the rainbow of the day-time sky and the river of the Milky Way in the night sky.’ (Worms & Petri Reference Worms and Petri1998, in Clarke Reference Clarke2014: 313). Kerry-Ann Winmar, of Noongar heritage, in her storybook (Winmar Reference Winmar2009), describes the stars as looking like the campfires of the ancestors. For the Pitjantjatjara, Western Desert (partly in WA):

… the Skyworld was split up into two groups—the summer sky (Orion, Pleiades and Eridanus) and the winter sky (Scorpio, Argo and Centaurus) … [the] summer sky was considered to be nganatarrka (nananduraka), meaning the generation of one‘s self, grandparents and grand-children. The winter sky was tjanamiltjan (tan-amildjan) and therefore of the parents‘ and children‘s generation level. (Clarke Reference Clarke2014: 314).

The Noongar narrative, Carers of Everything (Nannup Reference Nannup and Mia2008), partly related in Section 3.4, describes the creation of the Milky Way by a spirit woman who carried spirit children in her hair, up into the sky, where they became stars. In a similar account on a plaque in Victoria Park, Claisebrook, East Perth, she is referred to as the Charrnock Woman, with long white hair, and her campsite is the Hyades star cluster – Aldebaran is her fire. A nearby mosaic depicts her (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The Charrnock Woman mosaic, Claisebrook, East Perth. Hair, top right. Photograph by P. Forster.

The Charrnock Woman narrative, variously called Charnock, Junda and Jindalee, has many retellings by Noongar people, including by Elder Trevor Walley (b. 1957) on Utube (Walley Reference Walley2015), and Elder Toogarr Morrison (b. 1950) through story and in two large paintings in public buildings (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith2014). The Charrnock woman features in a songline from Bunbury to Geraldton to Wave Rock (Robertson et al. Reference Robertson, Stasiuk, Nannup and Hopper2016). A strand of her hair snapped off and created the lakes at Joondalup in Perth (ibid). During full moon, you can see her long white hair reflected in Lake Joondalup (City of Joondalup, n.d.). She left a footprint at Blackwall Reach alongside the Swan River (Robertson et al. Reference Robertson, Stasiuk, Nannup and Hopper2016). The sandbar in the Swan River at Point Walter is a strand of her hair (Parks and Wildlife Service WA, n.d., audio by Noongar Elder Marie Taylor). She left earth by leaping off Wave Rock, Hyden (Nannup Reference Nannup and Mia2008; Figure 5). The Claisebrook Plaque states that her man who ate spirit children lived in Bates Cave, otherwise known as Mulga’s Cave (Figure 6), near Hyden; and the first place where the spirit children returned to earth as stones was Hippos Yawn (Figure 7), at the base of Wave Rock.

Figure 5. Wave Rock where the Charrnock Woman launched herself into the sky. Photograph by P. Forster.

Figure 6. Bates Cave, also known as Mulga’s Cave, near Hyden, south-west WA. Photograph by P. Forster.

Figure 7. Hippo’s Yawn, near Wave Rock, where spirit children returned to Earth as stones. Photograph by P. Forster.

Akerman’s (Reference Akerman2016) notes collected over 40 yr engagement with Aboriginal people in the north-west Kimberley, document his observations on Wandjina spirit beings and culture including rock art depictions. The Milky Way is referred to in relation to creation on earth, moieties and initiation. For Wunambal people (Lommel Reference Lommel1997, in Akerman Reference Akerman2016: 108):

In the sky lives Wallanganda, the lord of the sky and at same time the personification of the Milky Way. Of Wallanganda it is said that he ‘made everything’. At first there was nothing on earth. Only Ungud [in the form of a large serpent] lived in the earth’s interior. Wallanganda cast fresh water down from the sky onto the earth. But Ungud ‘made the water deep’ and also caused it to rain on earth. Thus life could begin.

For Ungarinyin people, Walanganda is a sky hero who, with the hero pair Wodoi (Alpha Gemini) and Jungkun (Beta Gemini), are culture-bringing ancestors (Akerman Reference Akerman2016). The hero pair are primary moiety totems today. Walanganda is said to have:

… his sky ‘camp’ in a cave, and a second way out of this cave leads to ‘the other side of the sky’, where he hunts together with the shadows of great Wóndjina and where there is a world as there is in earth, only everything more beautiful and perfect. (Petri Reference Petri1954, in Akerman Reference Akerman2016: 109).

For Mowanjum peoples (Worrorra, Ngarinyin and Wunumbal of the Kimberley), Idjajir is the great creator and resides in Wallungunda, the Milky Way (Jorgenson, Reference Jorgensonn.d.). Idjajir sent the Wandjina and made the Gyorn Gyorn people (now represented in a distinctive art style) at the beginning of time. The Gyorn Gyorn were difficult to control so the Wandjina travelled back to the Milky Way and asked Idjajir for more Wandjina to help on earth. The new Wandjina gave law and culture to the Gyorn Gyorn. (ibid, painting caption for Gyorn Gyorn 2005, by Marjorie Mungulu, b. 1951).

In summary, I have uncovered relatively few WA Aboriginal narratives about the Milky Way. In them, the Milky Way variously represents the rainbow serpent, campfires, a spirit women and spirit children, moieties, Wandjina spirits, and Walanganda – a sky hero. Descriptions of Walanganda differ, including that he personifies the Milky Way (Lommel Reference Lommel1997, in Akerman Reference Akerman2016), that Walanganda is the name of the Milky Way which consists of many spirits (Hernandez Reference Hernandez1961, in Akerman Reference Akerman2016; Jorgenson, Reference Jorgensonn.d.), and that Walanganda is transformed at the end of his earthly existence into Unggud the serpent (Petri Reference Petri1954, in Akerman Reference Akerman2016).

4.4. Crux: The Southern Cross

Interpretations of the Southern Cross by Aboriginal people vary across Australia (Norris Reference Norris2016), including that, for people in the Kimberley, the Cross is an eaglehawk (Kaberry Reference Kaberry1939, in Norris). In South Australia, the Southern Cross is seen as the footprint of Waljajinna, the Eagle-hawk or Wedge-tailed Eagle (Aquila audax) (Bates, Reference Bates1904–1912b, in Leaman et al. Reference Leaman, Hamacher and Carter2016). The hatching of Eagle-hawk chicks corresponds with the heliacal rising of Crux, which may be the reason why the constellation is associated with Waljajinna (Leaman and Hamacher Reference Leaman and Hamacher2014).

Noongar man Rod Garlett, in describing his painting Noongar Boodja Wangkiny (Our Land Is Talking) (Garlett Reference Garlett2017: video), points to his depiction of the Southern Cross that has four claws of an eagle touching the four brightest stars, and says: ‘… waalitj is the eagle, and this symbol here of the Southern Cross, reminds us he [waalitj] was responsible for creating the laws of our Noongar land, our sea, and for its people.’

In the west Kimberley, the Southern Cross is Jina (eagle’s claw print) and the pointers are Gwuraarra (hitting stick) (Salisbury et al. Reference Salisbury2016). The claw print belongs to Warragunna (or Warakarna), the ‘Eagle Man’ or ‘Eagle-hawk’ (ibid). Bates (Reference Bates1929) recorded a narrative about Warragunna. He was kogga (uncle) to jindabirrbirr the wagtail, and joogajooga the pigeon. The three went hunting for honey of native bees. Warragunna went up the trees to retrieve it, but sent down only small portions. When they hunted langgur (opossum) and koordi (bandicoot), Warragunna did the killing, then ate the best bits. Realising Warragunna was greedy, the boys went to a koordi ground. Joogajooga made a deep hole, like a koordi’s nest. Jindabirrbirr sharpened the end of a stick, and they put the stick in the hole with the sharp point upwards. Next day, Warragunna came to the hole, and put his foot down, quickly and hard, to kill the koordi. The stick ran through his foot and he cried out. A sorcerer came and pulled it out, but:

… water came rushing out of the hole in Warragunna’s foot and … made a river … And Warragunna’s foot went up into the sky where it is called the Southern Cross by white people. (ibid: 6).

So, Jina (eagle’s claw print) symbolises greed. Perhaps the name Jina for Crux came about because eagles have four sharp claws which correlate with the four stars of Crux; and maybe the narrative came about because of the greed of eagle-hawks who fend off other birds from a kill until their own appetite is satisfied? Further, there is a language link in the naming of the Southern Cross by Aboriginal peoples: foot of Waljajinna (South Australia); Jina, eagle’s claw print (west Kimberley). In the Noongar language, jinna means foot (Moore Reference Moore1842: 134).

For people of the north-west Kimberley, the Southern Cross Pointers are white cockatoo feathers adorning the head of the sky hero Walanganda (Petri Reference Petri1954, in Akerman Reference Akerman2016). For Karadjeri people, south-west Kimberley, Marimari, a giant emu man:

… wanted to obtain water, but two large hawks called Dia came and speared him. All three are now visible in the sky: Marimari as the ‘Coal Sack’ and the Dia as the pointers of the Southern Cross. (Róheim Reference Róheim1945: 64).

From the north-west coast of WA, the Southern Cross is the camp of two mothers (Roberts & Mountford Reference Roberts and Mountford1974, in Johnson Reference Johnson2014). Pointers Alpha and Beta Centauri are their fires. They came to earth for food, carrying fire sticks which got out of control. People on earth captured the resulting fire. From Noongar Elder Noel Nannup:

The Southern Cross and the stars around it are really the head of a kangaroo. You can see the ears and the teeth, you can see the kangaroo’s back coming down and the tail going off. (Nannup Reference Nannup and Mia2008: 103).

Merninga-Gnudju Noongar Carol Pettersen (b. 1940), of the south coast WA, in her storybook (Petterson Reference Petterson2007), relates how four sisters go to a sacred place. They are chased away by men who attack them with spears, but they escape by fleeing to the sky, where they become the Southern Cross. In the version recorded by Hassell (Reference Hasselln.d.: 213–215), south-east coast WA, four sisters are sent to fetch water. Instead of coming straight back, they play. Men of the tribe find them playing and, as punishment, prod the girls in the carves of their legs with hunting spears. The girls run as fast as they can. A big wind springs up and blows them into the sky. They spread out to avoid spears thrown by the men, which is why they are not clustered like other stars. They stay up there because they are frightened, which is a lesson to other girls not to play when sent on a task, because they will never get to find a man and be married.

Hence the configuration of Crux is seen to match that of animals and named accordingly, and/or the Crux narratives address behaviour. Fire is referenced – fire in the sky is a recurring theme in WA narratives. Besides the pointers being the fires of two mothers, Aldebaran is the fire of the Charrnock Woman (Section 4.3) and/or the Milky Way is populated with campfires (Section 4.3). Fire in the sky is also where fire on earth originated: birds stole it from the Moon (Section 3.2); or it was brought by the pointers. These concepts for Crux and other stars exemplify Kelly’s (2016: 38) observation that: ‘stories aid memory of the sky patterns while the stars aid memory of the stories and their encoded content,’ including acceptable behaviour.

4.5. The Magellanic Clouds

Norris (Reference Norris2016) identifies a number of narratives about the Magellanic Clouds. They vary widely. In several, the Clouds are campfires of an old couple (e.g., Mountford Reference Mountford1956). For the Kamilaroi, Northern Territory, the Magellanic Clouds are where the spirits of the dead go (Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Anderson, Norris and Trudgett2014b). Noongar Elder Noel Nannup commented on the importance of Magellanic Clouds for people in south-west WA: in Goldsmith (Reference Goldsmith2014: 69), ‘… the Small Magellanic Cloud is associated with law and is sensitive and/or secret, and the Large Magellanic Cloud contains ‘everybody’s’ story, and is much more open.’; and, in Kerwin (Reference Kerwin2006: 69), ‘the Milky Way and the Megilion [sic] Clouds are The Seven Sisters Dreaming; it runs a long way down from the Pilbara region.’

Elders Jack Jugarie (b. 1927) and Jack Lannigan (b. 1924) of the east Kimberley, when interviewed by Goldsmith (Reference Goldsmith2014: 143), gave accounts of a man being speared or people being otherwise hurt, then, ‘… the Small Magellanic Cloud comes down like a misty, smoky cloud over the dead body, and takes blood out of the dead body.’ The person comes back to life, and after 2 or 3 d returns to the dead state. Goldsmith proposes the initial dead state may be trancelike.