1. Introduction

The COVID-19-induced lockdowns of 2020 brought many societal challenges. In the grand scheme of hardships during this period, those faced by public humanities scholars or research development professionals ranked very low on the list of major problems, and rightly so. However, there were challenges and these tended to centre on the difficulty of convening and building cross-disciplinary or cross-sector partnerships without being able to visit the physical spaces of an organisation, or even get to know a potential collaborator over a coffee in a mutually agreeable location. It was during this period that the authors of this article wondered whether the pandemic may have, in fact, presented an opportunity to think of ways to form innovative and sustainable partnerships without relying on formal meetings in unwelcoming committee rooms. Instead, we considered whether collaboration might be better served through a mixture of co-created events, workshops, and open forums, which bring people together (whether virtually or in-person) to think about the ways humanities scholarship can contribute to tackling a range of societal issues in the post-COVID-19 world.

There was also a specific challenge facing us connected to the status and perception of the arts and humanities in UK universities. In July 2023, the Department for Education announced plans to “crackdown on rip-off university degrees,” which, its authors argued, do not result in “good jobs” for graduates.Footnote 1 As arts and humanities subjects typically result in lower graduate salaries than STEM disciplines, the policy could be seen as a thinly veiled attack on non-STEM subject areas.Footnote 2 Such suspicions were heightened by the policy arriving after a 2021 funding consultation by the regulatory body, the Office for Students, that listed a selection of arts and humanities disciplines – music, dance, drama and performing arts, art and design, media studies, and archaeology – as not being of strategic importance to the government.Footnote 3 With a change of government in 2024, the United Kingdom saw a decline in overt attacks on the arts and humanities; however, at the time of writing, the newly formed Labour administration has initially viewed research and development (R&D) through the lens of an industrial strategy, focusing on applied research objectives, local economic growth, and industrial partnerships. The arts and humanities are not excluded from this arena, but participation may require the development of infrastructure that provides arts and humanities scholars with the skills and opportunities to forge cross-disciplinary and cross-sector partnerships.

In this short reflection, we will provide an account of the formation of the Engaged Humanities Lab at Royal Holloway as a response to the evolving and, at times, challenging R&D policy environment in recent years. The lab was designed as an agile, programmatic entity rather than a physical space to facilitate experimentation in collaborative cross-disciplinary and cross-sector practices, as well as providing training around interdisciplinary working, industry partnerships, and research communications. We will first explore the role of labs in the humanities, outlining how Pawlicka-Deger’s concept of “infrastructure of engagement” neatly captures how the Engaged Humanities Lab operated as a flexible vehicle for humanities-led experimentation in collaborative practice rather than being contained within and constrained by a defined physical locale.Footnote 4 We will then outline the reasons for the use of “engaged” humanities over the more familiar category of public humanities, before offering reflections on the lab’s activities and successes; its operational model, which focuses on intra-institution collaboration; and finally, provide recommendations for how to make humanities labs sustainable entities within higher education institutions.

2. Why a lab?

The idea of a lab, with its helpful associations with experimentation and evidence-building, appealed to us, and so our first step was to review the relevant literature on the history of labs and their place within humanities disciplines. This helped us to identify best practices and opportunities to try something new and to build a case for a lab with our academic, professional service, and management audiences. Labs are, of course, synonymous with scientific research and are rightly viewed as the critical base from which fundamental science is built. The emergence of labs in the early modern period also represented a paradigmatic shift in science, marking, as Owen Hannaway notes, a “new mode of scientific inquiry, one that involves the observation and manipulation of nature by means of specialized instruments, techniques, and apparatus.Footnote 5 It is through similar movements, either bottom-up transformations in methodological approaches or an evolving higher education policy environment, that the lab has become a meaningful form of infrastructure within the humanities in recent decades. The drive towards thinking about labs in the humanities has been a consequence of multiple structural shifts over the past thirty years from the increasing impact of digital technologies facilitating a move away from the library, archive, and office as the locales for doing humanities research, as well as the 2008 financial crisis accelerating what Zoe Hope Bulatis calls the “econocratic” scrutiny of humanities research, to a more recent focus on challenge-led research and university-industry collaborations.Footnote 6

In this context, humanities labs have sometimes emerged as defensive infrastructures, justifying the validity of humanities disciplines in research landscapes seeing increasing “scientification” of knowledge through the use of emerging digital and data-focused technologies.Footnote 7 This is accompanied by a public policy environment that regularly leans into a form of techno-utopianism by assuming that scientific innovation can solve multiple social challenges. John Beck and Ryan Bishop have also argued that the recent emergence of arts and humanities labs within universities and businesses represents a neoliberal re-imaging of 1960s’ arts and technology labs (themselves problematic through their connection to the military-industrial complex) and are therefore shorn of transformative potential: “Indeed, the virtues of innovation, creativity, adaptability, and collaboration are so widely promoted in the twenty-first century that they no longer refer to the capabilities of scientific or artistic elites but serve as the guiding imperatives of everyday social and economic life under neoliberal capital.”Footnote 8

A more optimistic interpretation of non-science labs can be found through the social lab movement, which Zaid Hassan argues has been brewing over a twenty-year period: “Hundreds of people around the world have been and are developing social labs. Thousands more have participated in them. There are labs focused on eliminating poverty, on water sustainability, on transforming media, on government, on climate, on social innovation, and on many more issues.”Footnote 9 Similarly, the rapid proliferation of digital humanities labs, institutes, centres, and departments over the last two decades can be seen as a bottom-up, researcher-driven movement focused on using digital technologies to increase the capabilities and methodologies on offer to humanities disciplines.Footnote 10 In the United Kingdom, notable examples of digital humanities infrastructure include the Sussex Digital Humanities Lab at the University of Sussex, the Digital Humanities Lab at the University of Exeter, the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College London, and the Digital Humanities Institute at the University of Sheffield.

In the United Kingdom and the United States, the lab boom has also spilled into university civic missions, with labs focused on policymaker engagement emerging in multiple forms. Durrant and MacKillop identified 46 existing policy bodies at UK universities.Footnote 11 Through a series of interviews, their research also highlighted the various drivers behind policy bodies in UK higher education, from research assessment requirements to institutional strategies around civic engagement. Labs outside of STEM disciplines have therefore multiplied exponentially, and one could argue that they have reached a point of saturation, yet the idea of creating a space for experimentation and collaboration remains powerful for humanities researchers feeling professional precarity. Humanities labs have therefore become a powerful tool for harnessing group work that crosses disciplinary and sectoral boundaries, as well as a mechanism for demonstrating the intellectual and societal possibilities of humanities-led work.

Pawlicka-Deger describes this proliferation of labs beyond fixed structures and the scientific method as the creation of the “infrastructure of engagement” whereby “a laboratory can be conceptualized as a way of thinking and acting that entails new social practices and new research modes.Footnote 12 Therefore, a lab can be established anywhere. The only condition for creating a lab is community: a lab is constituted by, and for, the people gathered together to address particular challenges.”Footnote 13 This idea was particularly appealing at Royal Holloway, an institution with considerable strengths in the arts, humanities, and social sciences outputs, as seen through its position in the 2021 Research Excellence Framework where Politics, Music and Drama, Psychology, Geography, and Modern Languages all ranked in the top 10 nationally.Footnote 14 Yet, despite success in research quality, Royal Holloway has historically struggled to match the quality of output with levels of external research income.Footnote 15 The development of the Engaged Humanities Lab, therefore, provided a practical research development opportunity as an entity around which humanities researchers could consider how their high-quality research outputs could reach wider audiences or attract external funding. However, the Engaged Humanities Lab also had a wider purpose that connected more to the social lab’s movement through being a vehicle to address social challenges and experiment with forms of engagement otherwise unavailable through lone-scholar working or the conventional circuit of academic conferences and symposiums. The lab would also be a space of co-creation, allowing non-university actors to articulate their own challenges and projects and propose methods for working together with the academy to solve such issues.

3. Why “engaged” humanities?

In naming the lab, we opted for “engaged” over the more established “public humanities” because, as Miriam Meissner, Aagje Swinnen, and Susan Schreibman point out, “engaged” humanities can, usefully, be read in two ways. It is both an adjective, connoting a commitment to someone or something, and a verb, meaning to draw in, motivate, mobilise, or involve an individual or group.Footnote 16 The Engaged Humanities Lab embraces and champions this arguably sharper edge to traditional public humanities. As Meissner, Swinnen, and Schreibman continue, “engagement provides a process-oriented and flexible concept to grasp how humanities scholarship makes a difference in society.”Footnote 17 Striving to make a difference, or, in Royal Holloway’s case, to articulate what it means to be a university of social purpose, is not simply a response to critiques of universities in recent years, or, in the case of the humanities, the all too familiar narratives of crisis and irrelevance.Footnote 18 Nor can it be explained solely by what Robyn Schroeder describes as “a generational shift in career orientation,” one in which academics have emphasised “social outcomes over private gain.”Footnote 19 It is a complex, shifting, and sometimes contradictory combination of principles and pragmatism, confidence and disciplinary angst, ambition, and humility.

While the “engaged” humanities is described here as a “sharper edge,” or a more process-oriented and change-focused cousin, to the more familiar concept of public humanities, it is noteworthy that engagement is increasingly the common denominator in what is a diverse field of public humanities practice and body of thought. Susan Smulyan, for instance, calls for a public humanities that is “collaborative, process-centred, and committed to racial and social justice,” a public humanities that is “transformative rather than simply translational,” and “undertaken by collaborative groups – including university faculty, staff and students – with communities outside the campus.”Footnote 20 Hiro and McDaneld describe this shift as being manifested in the move away from “the top-down standard of the public lecture and toward a more mutually enriching engagement in which campuses and communities form authentic and lasting partnerships.”Footnote 21 As Matthew Frye Jacobson argues, while this work remains rooted in the best methods of humanities disciplines, “the knowledge we produce … is often more expansive and dimensional for being generated in dialogue with diverse partners,” before continuing:

Our project is not merely to get the work of the university out into the world (though it is partly that, too), but to build new archives, create new paradigms, recover buried histories, and weave new narratives of the sort that can only be produced when guild members cease to speak among themselves exclusively.Footnote 22

Publicly engaged humanities research, therefore, not only provides a powerful counter to the narrative of crisis and irrelevance, it is also, for those involved, often an enriching and highly productive experience. As Sylvia Gale and Evan Carton persuasively argue, “[t]he best way to argue for the relevance of the humanities is not to keep asserting its value but to demonstrate what it is capable of doing, within, across, and beyond the university’s walls.”Footnote 23

4. A three-year experiment

The Engaged Humanities Lab was conceived as a means of supporting colleagues in this task, experimenting and testing what the humanities is capable of doing, and achieving, when projects are challenge-led and collaborative or participatory by design. As such, it falls into Daniel Fisher’s fifth category of publicly engaged humanities, detailed on the Humanities for All website and nodding to Pawlicka-Deger’s earlier coinage: the infrastructure of engagement.Footnote 24 Compared to Fisher’s other categories – outreach, engaged public programming, engaged research, and engaged teaching – infrastructure might not be the most obviously exciting type of public-engaged humanities activity. However, as an enabler, coordinator, and amplifier, it plays a crucial role. As Fisher explains, universities have invested in a variety of initiatives, frameworks, and institutions designed to support engagement activities. These include, but are not limited to, funding to support engaged humanities research, teaching, and programming; training schemes; centres and institutes dedicated to public or engaged humanities activities; event series, conferences, and consortia; and increasingly recognising and rewarding engagement in their criteria for staff promotion. The Engaged Humanities Lab combined many of these elements in pursuit of its three missions:

Challenges: to encourage and support ambitious challenge-led research.

Collaboration: to build and strengthen external partnerships.

Communication: to equip humanities scholars with the skills, tools, and opportunities to disseminate their research to new and wider audiences.

The lab was purposefully not designed as a physical space, the cost of which would have been prohibitive, but rather an iterative and adaptive programme of activities designed to help create the intellectual and social space to develop engaged humanities skills, experience, and partnerships. This flexibility means the lab’s work can adapt and respond to opportunities, such as targeted calls by funders or a challenge identified by a partner, and scale to the financial resources the university can commit in any given year.

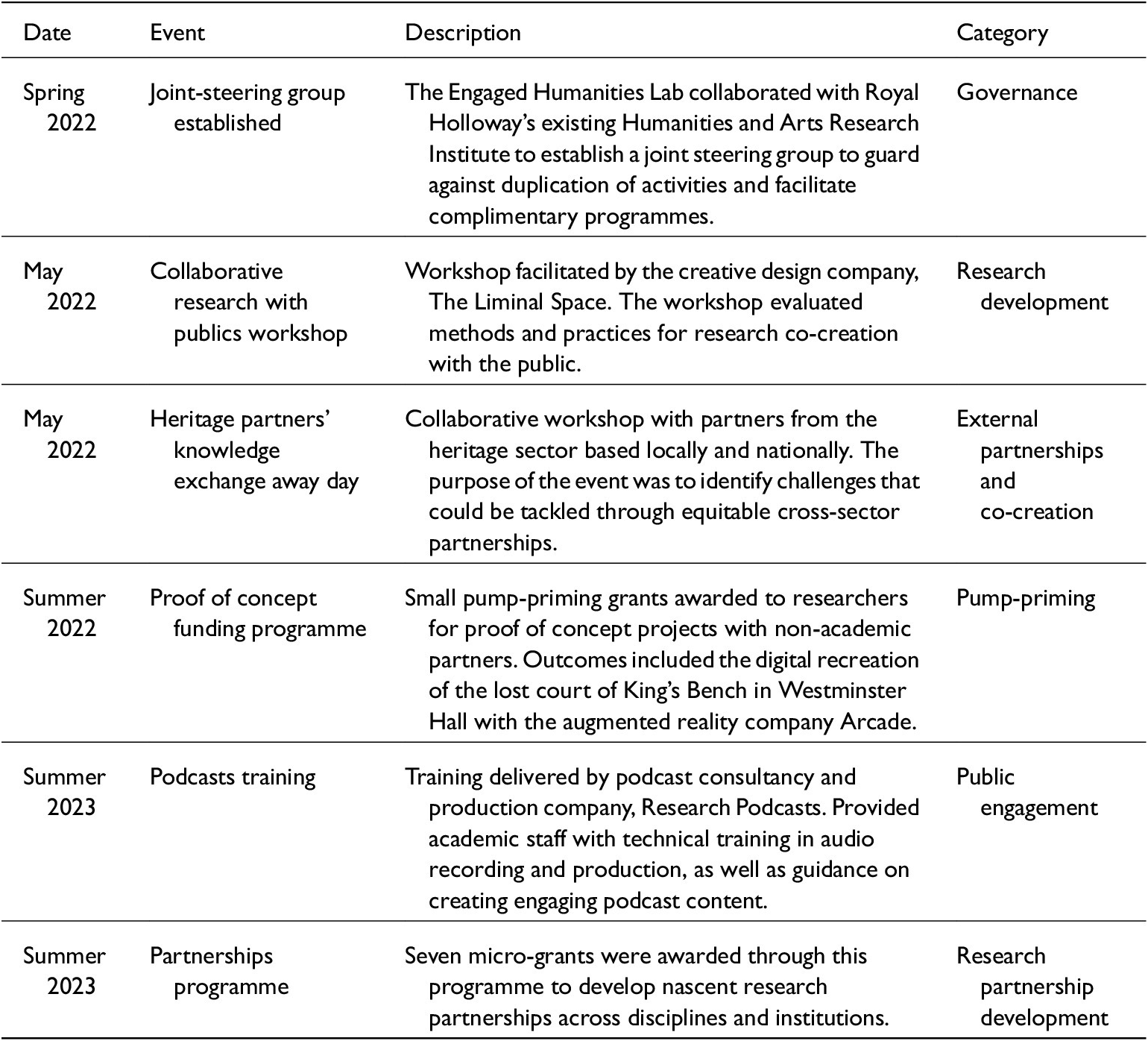

The Engaged Humanities Lab initiative at Royal Holloway demonstrated what infrastructures of engagement are capable of doing, and now, after three years, we can reflect on what has been achieved and what we have learnt from this experiment. The initial scoping work involved discussing the concept with the School of Humanities Research and Knowledge Exchange Committee in January 2021 to understand the level of interest and support from local academic leadership. This was followed by an online Engaged Humanities Day in May 2021, which attracted over 50 attendees from across the university, to showcase the successes and possibilities of engaged humanities research and explore the role of labs in the humanities. A working paper was then produced and presented to university senior management as a way of demonstrating the wide-reaching support for the development of the Engaged Humanities Lab and as a way of setting out a future path for the lab’s launch. The working paper also positioned the Engaged Humanities Lab against similar humanities lab concepts across the globe and noted how inspiration had been drawn from initiatives such as the Humanities Action Lab in the United States, which has created a unique coalition of universities, public bodies, and community organisations to tackle contemporary social challenges.Footnote 25 The Engaged Humanities Lab launched in Spring 2022, with small pockets of funding received via the university’s Quality-Related budget and the institution’s Higher Education Innovation Funding (HEIF). Table 1 provides a selected sample of activities undertaken during 2022 and 2023.

Table 1. Selection of activities and programmes delivered by the Engaged Humanities Lab at Royal Holloway, 2022–23

This is a table we constructed to visually demonstrate a programme of activity.

In its third, and potentially final year, operating with less funds than in previous years, the Engaged Humanities Lab focused on one partnership in particular. In 2023, the School of Humanities led Royal Holloway in entering into a five-year partnership with the Black Cultural Archives (BCA) in Brixton, London. BCA, the home of Black British History, grew out of a community’s response to discrimination in education; the devastating effects of racism in society and, in particular, the criminal justice system; and the Brixton Uprising of 1981. Its founders, including the inspirational Len Garrison, concluded that what was needed was a space where the community could come and find positive representations of themselves in history and culture. Royal Holloway’s partnership with BCA is built upon a shared commitment to equity, inclusive education, and transformative research. As part of this partnership, new digital educational resources have been produced; new public programming piloted; and, in the summer of 2024, £1.5 million was secured in Arts and Humanities Research Council funding for a landmark collaborative research project, Inclusive Histories, which, in partnership with the AQA exam board and six other museums and archives, will develop resources to support more inclusive teaching of UK political history in secondary schools.

For its part, the Engaged Humanities Lab has been key to broadening Royal Holloway’s academic engagement with BCA, bringing new colleagues to the Archives to collaboratively design and deliver new events for BCA’s families programme. These have included workshops exploring ephemera in the archive and the stories that can be unlocked through personal, family “archives”; the evolution and legacy of Black British music; and Black British writing and theatre as activism. These pilot activities have not only helped develop new ways in which BCA can activate its collections and engage the communities it serves, they have also provided our colleagues with an enriching experience that has equally benefited our own professional practice. As a result of this activity, we are now scoping funding opportunities to continue this work to activate and animate BCA’s collection in new and exciting ways. While collaborations between universities and external partners emerge all the time without the need for a lab, we have observed, in the case of Royal Holloway at least, that many of these tend to rely on narrow connections involving a single academic and a contact at a partner organisation, with inherent risks to these partnerships should one person move on from their current organisation. What the lab successfully enabled was a structured and supported framework to broaden engagement between partners, increasing the number of individuals involved and, consequently, the opportunities for collaboration.

5. Running the lab: Intra-institution collaboration

The Engaged Humanities Lab did not emerge out of a specific academic research group or interest area, which is the common way in which university research centres or institutes are formed, but rather due to a variety of competing institutional needs as identified through discussions with professional services, academic staff, and the university’s senior leadership. The idea developed initially within Royal Holloway’s Research and Innovation Department and, more specifically, from research development professionals who were looking for a way to effectively train and enthuse arts and humanities researchers in the area of external grant capture and collaborative research practices. Following discussions with the School of Humanities and the school’s existing arts and humanities research institute, the Humanities and Arts Research Institute (HARI), a joint HARI-Engaged Humanities Lab steering group consisting of academics, professional services, and postgraduate research students was created to guarantee coherence in programme development, buy-in from the academic community, and strategic oversight to ensure that there was alignment with wider institutional missions spanning research, teaching, and strategic partnerships.

The role played by professional services staff in conceptualising the Engaged Humanities Lab highlights the importance of what Whitchurch calls “third space professionals” in universities who have emerged as a result of a reorientation of administrative functions “towards one of partnership with academic colleagues and the multiple constituencies within whom institutions interact.”Footnote 26 Indeed, the success of the Engaged Humanities Lab was due to significant intra-institution collaboration rather than siloed working within departmental groups. The inclusion of staff from the Research and Innovation Department was particularly key in kick-starting the lab due to the department’s role in managing certain university funds (e.g., HEIF) and being the operational lead for a number of institutional strategies focused on research income, knowledge exchange, and research culture. By utilising a central university department, the Engaged Humanities Lab was also able to develop a communication strategy that reached a wide range of academic staff, whilst also making use of the significant skills and experience of research managers and administrators (RMAs) in staff training, partnership development, funder policies, and internal funding management. The interaction of academic expertise, operational “know-how,” and sensitivity to wider strategic objectives helped to create programmes of activities that had the greatest chance of reaching a broad selection of academics, maintained appeal to external partners outside of higher education, and, at the same time, connected to university-level strategies.

6. Conclusion: Making humanities labs sustainable

Establishing new infrastructures of engagement is easier than maintaining them. In this short concluding section, we offer some recommendations, based on our experience, for how universities might make infrastructures of engagement, like the Engaged Humanities Lab, more sustainable enterprises.

6.1. Multi-year institutional commitments

For initiatives like the Engaged Humanities Lab to be successful, institutions should financially commit to their existence for more than one financial year at a time. Whilst this is difficult due to the current UK funding system where hypothecated research funding sometimes appears at short notice, institutions should also be aware that uncertainty regarding future funding makes it much harder to build long-term relationships with external partners, which may, ultimately, jeopardise future inward investment. Additionally, by making multi-year commitments, longer project timelines can be established, which ensures that money can be spent more wisely and reflects the reality that partners’ timelines rarely align perfectly with that of the university’s financial year.

6.2. Joint academic and professional service leadership

The marrying of skills, insights, and experience brought to bear in joint academic and professional service leadership helps ensure that the activities of a humanities lab, or similar initiative, balance the interests of individual academics or research groups with the interests of the institution and funders.

6.3. Focus

More generalist labs, like the Engaged Humanities Lab, cannot solve all of the challenges facing the humanities, but it is tempting to design them in a way that makes bold claims regarding their societal and intellectual reach. Instead, it is important for such entities to be clearly focused on a manageable collection of initiatives, opportunities, and partners, especially when the leadership team is small, to allow for deeper and more meaningful engagement with colleagues, external collaborators, and audiences.

6.4. Key performance indicators

Engagement, like impact, can be difficult to quantify. Similarly, relationship building or the strengthening of an external partnership is hard to measure and may take years to produce results, particularly considering the time it takes for grant applications to be developed and assessed. While Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are essential in any initiative employing university resources, KPIs should account for the fact that some benefits may take years to yield quantifiable results. It is therefore important for an emerging humanities lab to think carefully about how it measures success, developing metrics and narrative frameworks that account for the long-term and less quantifiable aspects of engaged humanities work. Innovation in this area could not only offer practical institutional benefits in communicating the value of the work to decision-makers but also provide a wider public benefit in demonstrating the social impact of, for example, cross-sector partnerships or publicly engaged research communication.

At Royal Holloway, in launching the Engaged Humanities Lab, we were fortunate to have a leadership team committed to social purpose and the fulfilment of the university’s civic responsibilities, and if the lab experiment should end after three years, it will not be for want of an institutional commitment to the values it stands for or what it was attempting to achieve. In these difficult financial times for many universities, infrastructures of engagement are undeniably an expense that some cannot afford, and sometimes experimentation carries too high a financial risk. It is our hope, however, that the Engaged Humanities Lab experiment at Royal Holloway provides a useful model and some inspiration for future endeavours.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: M.S., C.D.; Formal analysis: M.S., C.D.; Methodology: M.S., C.D.; Project administration: M.S., C.D.; Writing – original draft: M.S., C.D.; Writing – review & editing: M.S., C.D.

Conflicts of interests

The authors declare none.