Health promotion, according to the WHO’s Ottawa Charter, aims to enable people to increase control over their health( 1 ). One of the core concepts of health promotion is empowerment. It can be defined as ‘a process by which people, organizations and communities gain mastery over their affairs’( Reference Rappaport 2 ). It is postulated that individual or psychological empowerment has a positive impact on people’s health and that empowered people engage in creating healthier environments (‘community empowerment’)( 1 ). Empowerment is often referred to as a complex construct( Reference Tremblay and Richard 3 ). It can be viewed as a process in or a means for health promotion, as well as a representation of the outcome or goal of successful health promotion initiatives( Reference Zimmerman 4 ). Manifestations of empowerment are highly context sensitive; they differ between target groups, settings and cultures( Reference Rappaport 2 ). In order to implement empowerment into practice, a wide range of approaches is used: participatory strategies, provision of social support to strengthen people’s self-esteem and self-efficacy, raising of critical consciousness, etc. However, ‘authentic’ empowerment is considered to be more than simply a technique or a strategic approach in health promotion, but rather a value-based attitude that underpins professional practice( Reference Woodall, Warwick-Booth and Cross 5 ).

Initially, the empowerment approach was used predominantly among marginalized communities in programmes in developing countries, for the obvious reason that poverty, suppression and powerlessness necessitate empowering strategies. Still today, the main focus of empowerment in health promotion in developing countries remains on vital issues such as access to drinking-water, health care and housing conditions. In industrialized countries, health promotion programmes are rather meant to engage people in living healthy (healthier) lives or creating healthy (healthier) environments in their communities.

Healthy nutrition is an important lifestyle behaviour that affects people’s health( Reference Sofi, Cesari and Abbate 6 ). However, unhealthy diets are highly prevalent in Western industrialized countries and are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality( Reference Danaei, Ding and Mozaffarian 7 ). Recent research increasingly addresses the influence of the food environment on an individual’s diet( Reference Osei-Assibey, Dick and Macdiarmid 8 , Reference Caspi, Sorensen and Subramanian 9 ). The constant availability of high-energy, sugared and high-fat foods in industrialized countries as well as modern-day lifestyle renders a healthy diet difficult.

Therefore, applying the concept of empowerment to the field of healthy nutrition seems promising. However, empowerment for healthy nutrition in a non-development context has not yet been studied comprehensively. Whereas the challenge of control (or even power) is obvious when working with disadvantaged communities struggling with vital problems, little is known about applying empowerment theory as well as empowering health promotion strategies to the field of healthy nutrition.

Thus, the starting point for the current systematic review was the question: How can the empowerment approach be applied to the subject of healthy nutrition within general, non-clinical populations?

The specific focus on measures for the general population is important, as programmes that use empowerment strategies within the field of nutrition are often directed towards patients suffering from nutrition-related diseases or from diseases that require diet changes (e.g. type 2 diabetes mellitus( Reference White 10 ), obesity( Reference Struzzo, Fumato and Tillati 11 , Reference Knutsen and Foss 12 )). However, in the health-care sector ‘empowerment’ is often used in a different way than in health promotion, i.e. in terms of ‘patient empowerment’ or self-management in regard to a certain disease( Reference Anderson and Funnell 13 ). Compared with empowerment in health promotion, patient empowerment works with narrower goals, predefined target groups and educational techniques which focus on the development of specific knowledge and skills. Thus, patient empowerment will not be within the scope of the current review and the focus on healthy nutrition will be set on the primary prevention aspects of a healthy diet.

Considering that the empowerment concept has been used by a growing number of scientific disciplines, a substantial, though very heterogeneous body of literature on empowerment and empowerment projects is now available. In recent years, systematic reviews on different aspects of empowerment have been conducted; the most comprehensive review was compiled by Wallerstein on behalf of the WHO( Reference Wallerstein 14 ). A more recent review focused on empowerment interventions for the elderly( Reference Shearer, Fleury and Ward 15 ). To date, no narrative or systematic review on the subject of empowerment and healthy nutrition has been published.

Thus the aim of the current systematic review was to identify studies that used an empowerment approach within the field of healthy nutrition. We present how empowerment was described, operationalized and implemented into practice and give an overview on how empowerment was operationalized in different settings and samples.

Methods

Studies which were included in the systematic review had to meet the following selection criteria: (i) the study had to be published as an original article; (ii) the concept of empowerment had to be essential for the intervention and therefore explicitly mentioned; (iii) the health-promoting measure/intervention had to be directed towards non-clinical populations; and (iv) healthy nutrition had to be the goal or one of the goals of the intervention (or was chosen as goal by the participants). ‘Healthy nutrition’ was defined as all nutritional issues beyond food safety and food security. Some examples of this might be promoting fruit and vegetable consumption or decreasing the intake of sugar-sweetened beverages. Finally, (v) studies had to be based on empirical data collection (i.e. qualitative or quantitative process or outcome parameters were reported).

Studies were excluded if the paper was a (systematic) review, comment, letter or conference abstract, if no abstract was available or if the language of the article was neither English nor German. Furthermore, studies that primarily targeted patients or (health care) professionals and studies in which interventions focused on food safety or food security in a developmental context were not considered relevant for the review. Finally, articles that described a (theoretically derived) concept for an intervention, but did not report its implementation, as well as articles describing the status quo or the results of a needs assessment were not included.

Articles were identified by database searching (PubMed, PsycINFO, Web of Science and Psyndex). The last database updates considered were from July 2014. Title, abstract and keywords were searched with the following search term: ((empowerment OR participatory action research/action research OR community-based participatory action research/CBPR) AND (nutrition OR food OR eating OR diet OR overweight OR obese/obesity)).

A secondary search was conducted within: (i) journals related to health promotion, participatory research and community psychology which were not registered in the databases; and (ii) the references of included studies and within the references of existing systematic and non-systematic reviews on empowerment and health promotion( Reference Wallerstein 14 – Reference Wiggins 18 ). This procedure yielded the identification of eleven additional studies. Two of them were considered for eligibility by reading the full-text papers. However, none of them were finally included.

Titles and abstracts of the articles were initially screened for their fulfilment of selection criteria. Two of the authors (S.B., J.R.) conducted the screening procedure independently from each other. Cases of non-accordance were discussed afterwards until consensus was reached. Subsequently, the remaining potentially eligible studies were appraised in detail by reading the full-text papers.

Summary tables were designed to gather the study characteristics of interest (see Tables 1 and 2). The corresponding data were extracted by S.B. As for the definition and conceptualization of the empowerment approach, information was extracted from the articles according to the phrasing of the authors.

Table 1 Main characteristics of the studies included in the present review

* Different aspects of the study are reported in two/three journal articles.

Table 2 Study characteristics for issues related to empowerment and healthy nutrition and primary results

* Verbatim quotations.

† Interventions of many studies pursue and evaluate other goals, too. However, for the purpose of the current review, the table focuses on nutrition-related aspects.

The systematic review was conducted based on the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) Statement in order to assure quality of the search process and adequate reporting within the present paper( Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff 19 ).

Results

Study selection

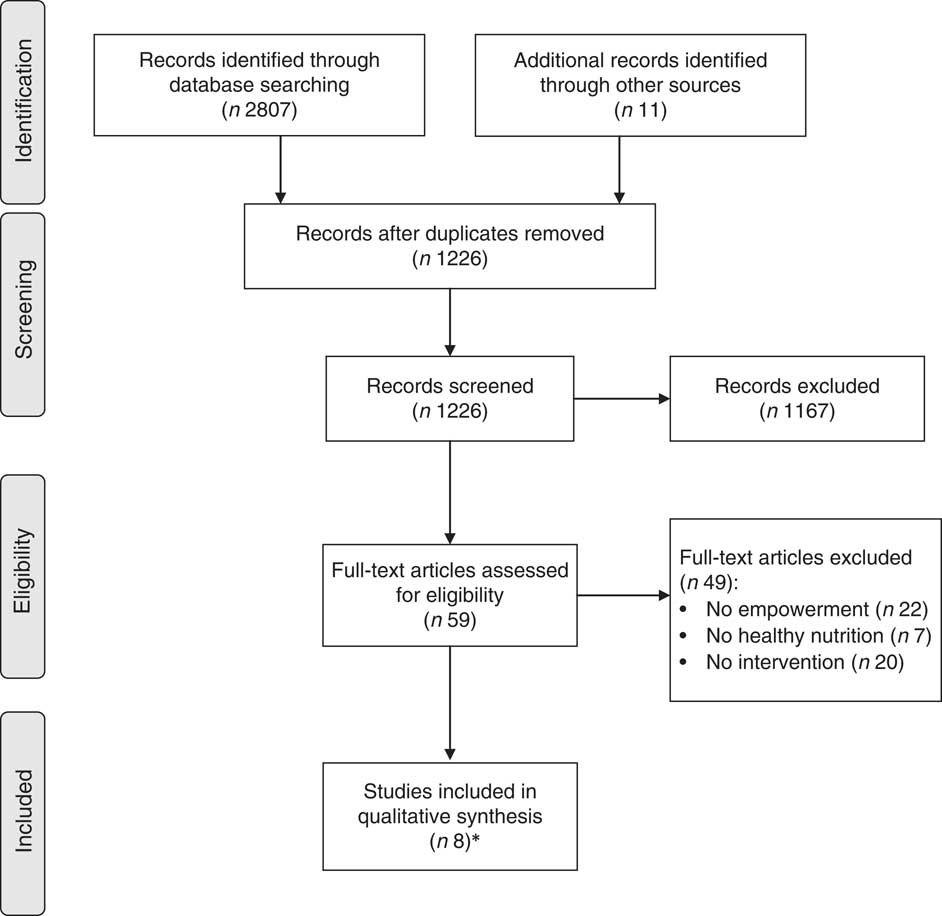

The database search yielded 2807 results (1515 in PubMed, 265 in PsycINFO, 1027 in Web of Science); a secondary search yielded eleven additional results. After the exclusion of duplicates, there were 1226 articles eligible for further screening. The screening of title and abstract according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria led to fifty-nine articles which were then examined as full-text papers. Finally, eight studies were included in the current systematic review. The process of study selection is depicted in a flow diagram (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of the study selection process (*eight studies were finally included; two of them were reported in two journal articles and one was reported in three journal articles)

Study characteristics

Table 1 provides an overview of the main characteristics of the eight included studies( Reference Backman, Scruggs and Atiedu 20 – Reference Jurkowski, Lawson and Mills 31 ). All studies were performed in Anglophone or Scandinavian countries within the last two decades. Seven out of eight studies targeted specific groups defined by age, sex or membership in specific communities: students, women (×3), parents, employees and senior citizens. One study was directed towards a community as a whole. Except for the study by Gadin et al.( Reference Gadin, Weiner and Ahlgren 21 ), the target groups, or rather the participants, were described as socio-economically disadvantaged persons.

The review included five intervention studies using quantitative research designs to conduct outcome evaluations, as well as three (participatory) action research projects using qualitative methods for data collection and analysis. Thus, the sample sizes of the studies varied considerably, ranging from forty-six to 1685 participants. Two out of three qualitative studies did not report the exact sample size; the intervention was done within the setting of pre-existing groups in a community that varied in size over time( Reference Robinson, Eceleston and McEvoy 25 , Reference Travers 26 ).

A range of different indicators was employed for evaluation in the studies. In the five (quasi-) experimental intervention studies, different aspects of participants’ nutrition behaviour was assessed as one of the outcomes. The indicators for nutrition behaviour ranged from detailed information on nutrient intake( Reference Lassen, Thorsen and Sommer 22 ) to single-item measures( Reference Baffour and Chonody 28 ). Additionally, two studies (the ones by Backman et al. and Jurkowski et al.( Reference Backman, Scruggs and Atiedu 20 , Reference Jurkowski, Lawson and Mills 31 )) measured participants’ empowerment as an intervention outcome and/or mediator on intervention outcome. The (participatory) action research studies applied qualitative methods stemming from a variety of research approaches (content analysis, grounded theory, case study). Travers’ analysis focused on group processes (including empowerment) during the course of the project( Reference Travers 26 , Reference Travers 27 ), while Robinson et al.( Reference Robinson, Eceleston and McEvoy 25 ) and Gadin et al.( Reference Gadin, Weiner and Ahlgren 21 ) did not refer specifically to empowerment in their analyses. They rather explored practical themes which emerged during the interventions.

Table 2 illustrates how the concepts of empowerment and healthy nutrition were operationalized in the included studies. In their respective rationale, most studies referred to the key message of empowerment as defined by WHO: taking control over one’s own life.

However, the operationalization of this core concept of empowerment varied across the articles. In the description of intervention methods, some studies did not refer to empowerment at all, while others briefly stated that participants were involved in decision-making processes. The participatory (action) research projects operationalized empowerment by means of group discussions with the participants. These projects underscore the importance of giving people a voice and considering their individual needs. In Travers’ study( Reference Travers 26 , Reference Travers 27 ) participants expressed their concerns about pricing inequity in their local supermarkets. During the course of the project they succeeded in influencing pricing policies. However, for the studies by Gadin et al.( Reference Gadin, Weiner and Ahlgren 21 ) and Robinson et al.( Reference Robinson, Eceleston and McEvoy 25 ), it remains unclear whether participants’ nutrition-related needs and other issues – arising from group discussions – could be transferred into practical activities.

All interventional measures were initiated by researchers and/or health professionals. Some of them involved local experts or staff from community organizations to facilitate implementation. The study by Jurkowski et al.( Reference Jurkowski, Lawson and Mills 31 ) trained parents as co-faciliators for other parents in order to provide peer support.

The included quantitative studies were heterogeneous in their approach to healthy nutrition. The study reported by Lassen et al.( Reference Lassen, Thorsen and Sommer 22 ) explicitly focused on healthy nutrition, while the studies reported by Baffour and Chonody( Reference Baffour and Chonody 28 ), Backman et al.( Reference Backman, Scruggs and Atiedu 20 ), Jurkowski et al.( Reference Jurkowski, Lawson and Mills 31 ) and Lupton et al.( Reference Lupton, Fonnebo and Sogaard 23 , Reference Lupton, Fonnebo and Sogaard 24 ) aimed at different health-related behaviours (e.g. physical activity, screen-related behaviour of children), one of which being healthy nutrition. Except for the study by Baffour and Chonody( Reference Baffour and Chonody 28 ), the quantitative studies revealed significant improvements in nutrition-related (parenting) behaviour to varying extents due to the intervention. Both Backman et al.( Reference Backman, Scruggs and Atiedu 20 ) and Jurkowski et al.( Reference Jurkowski, Lawson and Mills 31 ) assessed empowerment as an outcome in their studies. Their interventions succeeded in increasing participants’ levels of empowerment. Furthermore, Jurkowski et al.( Reference Jurkowski, Lawson and Mills 31 ) could demonstrate that behaviour (improvements in parenting practices) was mediated by empowerment (i.e. changes in empowerment were associated with behaviour changes).

While study results on nutrition behaviour seemed generally positive, the evaluation of most studies was poor. Only the study by Lassen et al.( Reference Lassen, Thorsen and Sommer 22 ) used a randomized controlled design, the other studies were evaluated by pre-test/post-test designs with or without control groups.

The included participatory (action) research projects did not aim to address healthy nutrition from the start, but were concerned with healthy nutrition because the participants themselves raised this issue during the course of the projects.

It was not possible to analyse how empowerment was operationalized in different settings and samples due to the small number of studies included.

Discussion

Principal findings

The aim of the present study was to explore the various ways of applying the empowerment concept to the topic of healthy nutrition by conducting a systematic review. It resulted in the inclusion of only eight studies. Given the widespread dissemination of health promotion programmes for healthy nutrition and initiatives utilizing an empowerment approach, this is a surprisingly low number. It seems that promoting healthy nutrition via an empowerment approach may be unfamiliar to scientists, politicians and stakeholders in the nutrition community as well as in the health-care sector. All studies included in the review had been conducted in Anglophone or in Scandinavian countries. This finding could be due to one of the inclusion criteria (articles had to be written in English or German language) or may reflect a greater familiarity with the empowerment theory in health promotion in these countries.

Additionally, some studies indicated that implementing the principles of the empowerment concept can be challenging. Many tensions arise in everyday practice( Reference Jacobs 32 , Reference Ozer, Newlan and Douglas 33 ) as well as in scientific evaluation( Reference Brandstetter, McCool and Wise 34 ). This may be particularly relevant for the subject of ‘healthy nutrition’. People’s views on healthy diets vary considerably and are strongly linked to their individual experiences( Reference Bisogni, Jastran and Seligson 35 ). Therefore, when using an empowerment approach, it could be difficult to integrate participants’ individual views and needs into the ‘official’ recommendations and guidelines for a healthy diet. In addition, participants may generally be accustomed to teacher-centred educational approaches, especially in regard to the subject of nutrition and eating.

The authors of the studies included in the current review referred to a combination of theories and concepts, such as the (socio-) ecological model or the socio-cognitive theory, in addition to the empowerment concept. This theoretical eclecticism is typical for health promotion and reflects common practice( Reference Tremblay and Richard 3 ). However, it poses a challenge for theory-based advancements and evaluation methods.

Within many of the included studies and their respective intervention projects, the explicit measures or methods used to operationalize empowerment were not described in detail. The only exceptions were the studies by Travers( Reference Travers 26 ) and Jurkowski et al.( Reference Jurkowski, Lawson and Mills 31 ); they provided extensive information on the theoretical background of their projects, on the reasons for using an empowerment approach and on how the concept of empowerment emerged in the intervention. As far as the other included studies are concerned, we would have expected to learn more about how the goal of enabling people to take control over their lives was achieved in the specific intervention measures or what made the particular intervention an empowerment intervention. Unfortunately, due to incomplete or imprecise reporting, it was frequently unclear how the theoretical description of empowerment corresponded to the implemented measures in the practical intervention projects( Reference Backman, Scruggs and Atiedu 20 – Reference Robinson, Eceleston and McEvoy 25 , Reference Baffour and Chonody 28 ).

Empowerment and behaviour

The relationships between empowerment and behaviour (change) are various. The link might be unidirectional, reciprocal or even non-existent. This applies to the field of nutrition behaviour (change) as well.

From a theoretical point of view, tensions between empowerment and behaviour (change) arise if conceptualizations of empowerment, health-promoting behaviours and health are derived from different paradigms. Assuming a narrow bio-medical model of health will impose difficulties on arguing how empowerment goals could translate into health. From this perspective, an increased level of autonomy, an example for an empowerment goal, has nothing in common with making healthier food choices. However, referring to a more comprehensive understanding of health (e.g. according to the definition by the WHO), the links between being empowered and experiencing autonomy, on the one hand, and bio-psycho-social health, on the other hand, are obvious, as states of empowerment and the feeling of autonomy represent health per se just as they are assumed to be fundamental basics of health. Rappaport argues accordingly, when he states that a certain behaviour can be seen both as an expression of health as well as an expression of empowerment( Reference Rappaport 2 ). Tengland( Reference Tengland 36 ) provides a detailed discussion on which empowerment goals (e.g. autonomy, control) are related to which health (behaviour) goals. He suggests that health-related abilities (e.g. self-confidence, self-efficacy) might mediate the relationship between empowerment and health, but that there are also empowerment goals pursued for their own sake.

This discourse is not novel in the field of health promotion, but it seems especially crucial for health promotion in terms of healthy nutrition. Still, the predominant paradigm in nutrition sciences is a bio-medical one, which might explain why empowerment is still used scarcely, as was shown in the current systematic review.

Strengths and weaknesses

To the best of our knowledge, the current systematic review is the first one on the subject of empowerment and healthy nutrition. Taking into account the interdisciplinary quality of this area in health promotion, we chose a search strategy which encompassed databases in bio-medical as well as social sciences. Furthermore, quantitative as well as qualitative studies were considered for inclusion in the review. The database search and study selection were performed in a systematic and documented manner, based on the PRISMA Statement for conducting systematic reviews.

However, there are some limitations to the review. We used a search strategy that was restricted to established scientific databases and scientific journals from the field of health promotion and excluded various types of grey literature. Particularly in the field of health promotion, there exists a considerable amount of reports which have never been published in scientific journals and reporting and publication biases cannot be excluded. Thus, all conclusions drawn in the present paper are limited to the ‘established’ scientific literature available via database-searching and hand-searching. We do not know how this search strategy may have affected the results of our review.

Conclusion

Overall, the concept of empowerment has scarcely been applied in health promotion programmes focusing on healthy nutrition. Probably the public health discipline that has employed empowerment interventions the most is the field of HIV/AIDS prevention. HIV/AIDS prevention empowerment strategies have been shown to improve health status by increasing condom use and reducing HIV infection rates( Reference Wallerstein 14 ) and may inspire further empowerment interventions in other disciplines.

Many studies included in the current systematic review lack detailed and comprehensible descriptions of implementing the empowerment concept. Detailed analyses could not be completed due to the low number of studies included. Further research on empowerment in health promotion focusing on healthy nutrition is urgently needed. Researchers should especially focus on thorough descriptions of implementing empowerment in practice.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This study was supported by a grant from the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) (‘Innovations in Nutrition’). BMBF had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: S.B., J.C. and J.L. contributed to the research design. S.B. and J.R. conducted the database searching and the screening procedure. S.B. drafted the manuscript. All authors commented on drafts and read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethical approval was not required.