Undernutrition including stunting and suboptimal breast-feeding accounts for 45 % of all childhood deaths( Reference Black, Victora and Walker 1 ). It is estimated that 30 % of the world’s stunted children live in Asia, with more than 60 million living in India; 31 % of the developing world’s total( Reference Black, Victora and Walker 1 , 2 ). Inadequate complementary feeding (CF) has been linked to these outcomes.

The WHO defines CF as: ‘The process starting when breast milk alone is no longer sufficient to meet the nutritional requirements of infants, and therefore other foods and liquids are needed, along with breast milk’( 3 ). CF therefore focuses on bridging the gradual transition between 6 and 24 months from exclusive breast-feeding to solid foods eaten by the whole family alongside breast-feeding.

Poor complementary feeding practices (CFP) have been linked to increased risks of respiratory and gastrointestinal infections, underweight and mortality( Reference Davies-Adetugbo and Adetugbo 4 – Reference Macharia, Kogi-Makau and Muroki 6 ). CF is also important for reducing stunting, which is a current policy priority in India( Reference Stewart, Iannotti and Dewey 7 – Reference Avula, Raykar and Menon 9 ). Despite this, in two published non-systematic reviews on CFP in India, Ramji and Engle noted that CF was often started at inappropriate times( Reference Ramji 10 , Reference Engle 11 ). There was also inappropriate quantities and diversity of complementary foods, with only 55 % of South Asian (SA) infants consuming appropriate complementary foods by 6–8 months of age and growth retardation notable by 2 years of age( Reference Senarath and Dibley 12 , Reference Gragnolati, Shekar and Das Gupta 13 ).

In policy, there has been recent increasing focus on CF. The 2010 WHO Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) guidelines, an internationally ratified framework adopted in India, emphasize as a global public health recommendation that infants should be exclusively breast-fed for the first 6 months of life to achieve optimal growth, development and health( 14 ). Thereafter, infants should receive safe and nutritionally adequate complementary foods while breast-feeding continues for up to 2 years of age or beyond.

With no previously published systematic review identified, we aimed to assess the adequacy of CFP based on IYCF recommended criteria for minimum dietary diversity, meal frequency and timing of CF introduction. We also aimed to investigate barriers and promoters for appropriate CFP in SA children under 2 years old. By doing so, we hope to inform future work in developing and assessing the effectiveness of culturally appropriate interventions to improve CFP across these communities.

To limit the scope of our review, we focused on SA families residing in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and high-income countries.

Methods

Due to the vast number of publications identified, the present review (PROSPERO registration number CRD42014014025) summarizes publications on CFP in SA families in India only, with concurrent reviews summarizing publications on CFP in SA families in high-income countries (L Manikam, R Lingam, I Lever et al., unpublished results), Pakistan( Reference Manikam, Sharmila and Dharmaratnam 15 ) and Bangladesh( Reference Manikam, Robinson and Kuah 16 ), respectively. High-income countries were included to investigate any differences in practice for SA who may have emigrated.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria.

-

∙ Participants: children aged 0–2 years, parents, carers and/or their families.

-

∙ Outcomes: adequacy of CF (based on minimum dietary diversity and meal frequency), timing of introduction of CF and barriers/promoters to incorporating WHO recommended CFP.

-

∙ Language: studies published in English, or with translation available.

-

∙ Year: published from 2000 or later.

We excluded studies focusing solely on exclusive breast-feeding and interventional studies. Studies focusing on subgroups, such as children with co-morbidities, were considered eligible in principle.

In the IYCF indicators, introduction of CF is assessed as the proportion of infants aged 6–8 months who receive solid, semi-solid or soft foods. In contrast, minimum dietary diversity (MDD) is assessed by the proportion of children 6–23 months of age who receive foods from four or more food groups. The seven WHO IYCF recommended food groups are( 14 ):

-

1. grains, roots and tubers;

-

2. legumes and nuts;

-

3. dairy products (e.g. milk, yoghurt, cheese);

-

4. flesh foods (e.g. meat, fish, poultry and liver/organ meats);

-

5. eggs;

-

6. vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables; and

-

7. other fruits and vegetables.

While the consumption of Fe-rich or Fe-fortified foods is commonly assessed as a separate IYCF indicator, this was incorporated within dietary diversity for ease of interpretation in the current review.

Finally, minimum meal frequency (MMF) is assessed by the proportion of breast-fed and non-breast-fed children 6–23 months of age who receive solid, semi-solid or soft foods (also including milk feeds for non-breast-fed children) the minimum number of times or more per day: two times for 6–8 months, three times for 9–23 months and four times for 6–23 months (if not breast-fed).

Due to the nature of the topic, all study types (qualitative, quantitative or mixed) were included to ensure the diversity of evidence was captured and summarized, to be of relevance to both policy makers and health and social care professionals.

Information sources

A search strategy was devised to search the following databases: MEDLINE, BanglaJOL, EMBASE, CINAHL, Global Health, Web of Science, OVID Maternity & Infant Care, The Cochrane Library, POPLINE and WHO Global Health Library. The WHO ICTRP (International Clinical Trials Registry Platform) was also searched. Searches were conducted in December 2014 and updated in June 2016.

Members of electronic networks on @jiscmail.ac.uk including minority-ethnic-health and networks (e.g. South Asian Health Foundation) developed from the Specialist Electronic Library for Ethnicity and Health were contacted to request any additional or unpublished material from members of the networks. We sought information specialist assistance to attempt to acquire unpublished material from each paper itself, and contacted study authors where possible. Bibliographies of included articles were also hand-searched for possible additional publications.

Search strategy

The search strategy included terms for ‘feeding’, ‘South Asian’ (including terms specifying all major subgroups) and ‘children’. For example, the search strings used for MEDLINE were the following.

Term 1: children <2 years

Infant OR Baby OR Babies OR Toddler OR Newborn OR Neonat* OR Child OR Preschool OR Nursery school OR Kid OR Pediatri* OR Minors OR Boy OR Girl

Term 2: feeding

Nutritional Physiological Phenomena OR Food OR Feeding behavior OR Feed OR Nutrition OR Wean OR fortif* OR Milk

Term 3: Asians

Ethni* OR India* OR Pakista* OR Banglades* OR Sri Lanka OR Islam OR Hinduism OR Muslim OR Indian subcontinent OR South Asia

Study selection and data extraction

In total, 45 712 titles and abstracts were screened against inclusion criteria. Two reviewers assessed these papers independently, with conflicts resolved by discussion with the team. In view of the large number of articles deemed eligible for full-text review, articles published before the year 2000 were excluded. In total, 44 852 titles and abstracts were excluded.

This left 860 potentially eligible full-text articles describing CFP in SA children, which were independently reviewed by two reviewers. One hundred and thirty-one full-text articles were ultimately extracted, of which seventy-three were relevant to India, seventeen were relevant to Pakistan, thirty-six were relevant to Bangladesh and ten were relevant to high-income countries.

Data were extracted by a single reviewer using a piloted modified worksheet including: country of study; study type; study year; study objectives; population studied, eligibility criteria and illness diagnosis; study design; ethical approval; sampling; data collection and analysis; feeding behaviours; adequacy of CFP; timing of initiation of CF; bias; value of the research; and weight of evidence. A second member of the research team checked each extraction, with further checking taking place as necessary.

Result synthesis

The eligible studies tended to address very broad research questions, were conducted using qualitative and/or quantitative and/or descriptive methods, and were not presented following standardized reporting guidelines (e.g. STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) for observational studies or COREQ (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research) for qualitative research). Meta-analyses were therefore not undertaken.

To standardize study classifications, the formal definitions below were utilized and applied( Reference Porta 17 , 18 ).

-

1. Intervention study: a study in which patients are assigned to a treatment or comparison group and followed prospectively.

-

2. Cohort study: an observational study in which a group of patients are followed over time. These may be prospective or retrospective.

-

3. Cross-sectional study: an observational study that examines the relationship between health-related characteristics and other variables of interest in a defined population at one particular time.

-

4. Case–control study: a study that compares patients who have a disease or outcome of interest (cases) with patients who do not have the disease or outcome (controls).

-

5. Qualitative: a study which aims to explore the experiences or opinions of families through interviews, focus groups, reflective field notes and other non-quantitative approaches.

-

6. Mixed methods: a study that combines both quantitative and qualitative methodology.

In view of the considerable heterogeneity among the studies identified in terms of methods, participants, interventions and outcomes, a narrative approach to synthesis was utilized using guidance developed from the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) and the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)( 19 – Reference Popay, Roberts and Sowden 22 ).

The evidence reviewed is presented as a narrative report, with results broadly categorized following IYFP indicators on: (i) adequacy of CFP, comprising dietary diversity, meal frequency, timing of introduction of CFP, consumption of Fe-rich foods and sources of advice for feeding; and (ii) barriers/promoters influencing CFP.

Barriers were defined as obstacles or impediments to achieving correct CFP( 23 ), while promoters were defined as supporters to achieving correct CFP( 24 ). These were sub-categorized into factors influencing at the family level (e.g. family members) and the organizational level (e.g. health-care providers, hospitals, political bodies).

Quality assurance

The CRD guidance emphasizes the importance of using a structured approach to quality assessment when assessing descriptive or qualitative studies for inclusion in reviews. However, it acknowledges the lack of consensus on the definition of poor quality with some arguing that using rigid quality criteria leads to the unnecessary exclusion of papers( 19 ).

In our review, the EPPI-Centre Weight of Evidence Framework was used to allow objective judgements about each study’s value in answering the review question. It examines three study aspects: quality of methodology, relevance of methodology and relevance of evidence to the review question, and categorizes them into ‘low’ (L), ‘medium’ (M) or ‘high’ (H)( Reference Gough 25 ). An average of these weightings is taken to establish the study’s overall weight of evidence (WOE), also rated as L, M or H. Two independent reviewers performed this evaluation, with additional arbitration by other team members where required. Studies with an overall WOE=L are included in the table summarizing included studies but are not discussed further within the ‘Results’ or ‘Discussion’ section below.

Results

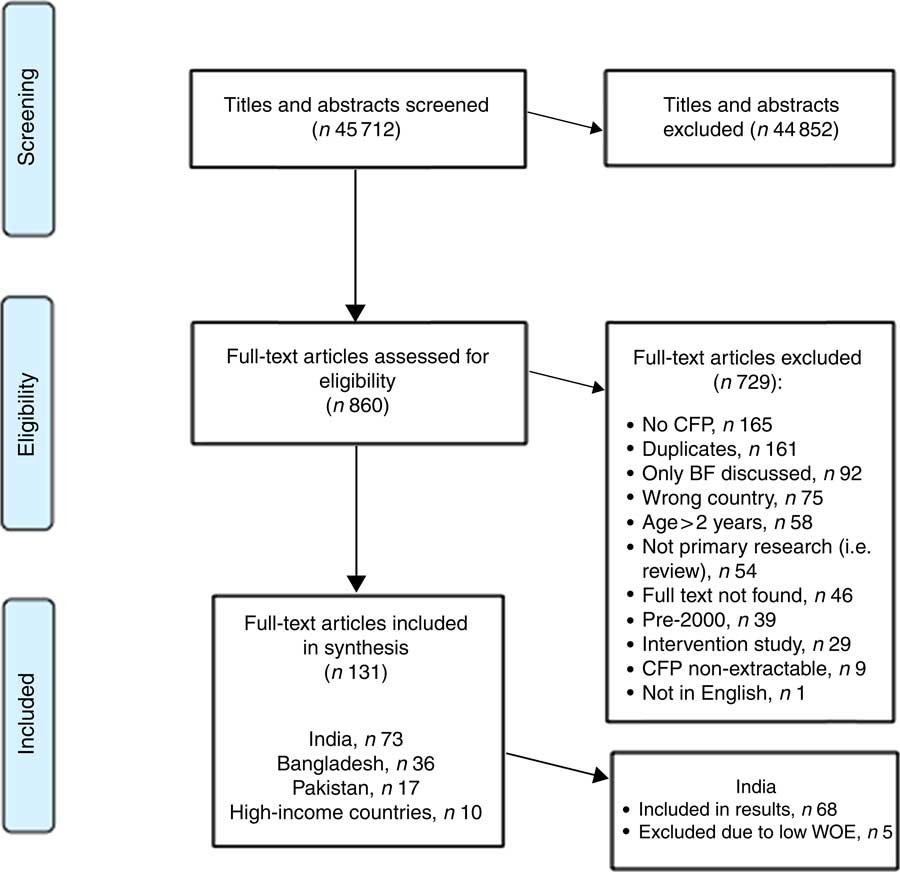

Of the 45 712 studies identified, seventy-three studies focusing on CFP in SA families in India were ultimately included in the current systematic review. The study selection process is denoted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Study selection process for the current systematic review (CFP, complementary feeding practices; BF, breast-feeding; WOE, weight of evidence)

Study and participant characteristics

These seventy-three studies consisted of sixty-four cross-sectional, seven cohort, one qualitative and one case–control. Sixty-eight studies met Weight of Evidence criteria and were included in the main results. Their participants included a total of 125 326 children and 5705 mothers or caregivers when infants were not reported. Twenty-one studies reported details of the religion of participants, which was Hindu majority in nineteen samples and Muslim majority in two samples.

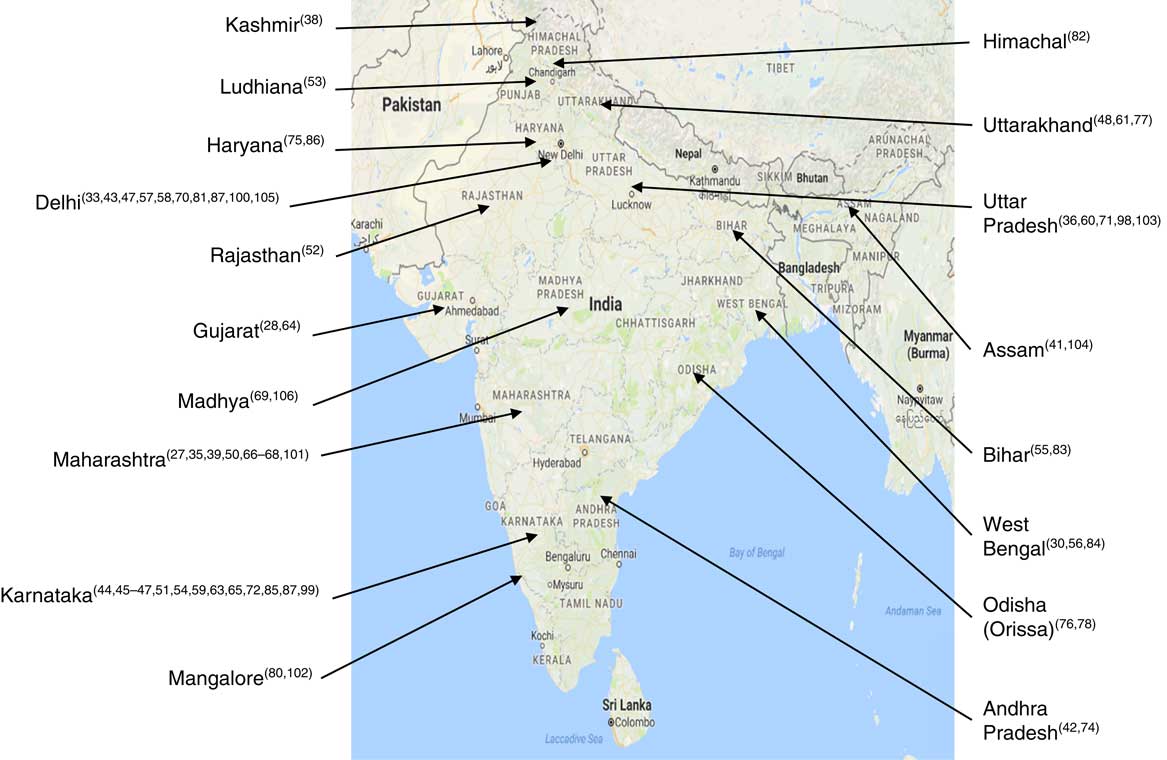

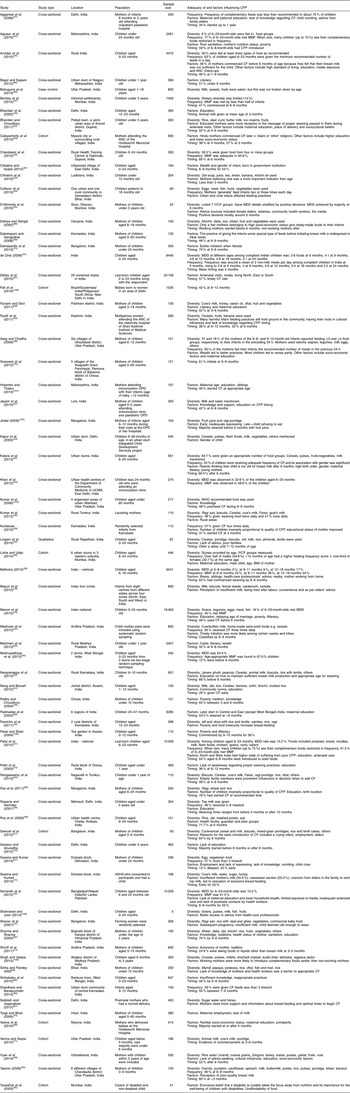

Table 1 summarizes all included studies. Figure 2 illustrates the study locations of sixty-three of these seventy-three included studies; the remaining nine do not detail precise study locations due to being described as ‘national’, ‘various’, ‘urban’ or ‘rural’ without specifics. Table 1 contains further details of study locations.

Fig. 2 (colour online) Location map of sixty-three studies included in the current systematic review (map courtesy of Google Maps; data © 2017 Google)

Table 1 Summary of studies included in the current systematic review

CFP, complementary feeding practices; ANC, antenatal clinic; OPD, outpatient department; ASHA, Accredited Social Health Activist; CF, complementary feeding; MMF, minimum meal frequency; IYCF, infant and young child feeding; MDD, minimum dietary diversity.

Table 2 presents the Weight of Evidence awarded to each of the studies. Thirteen studies had an overall WOE rating of H, fifty-five studies an overall WOE rating of M, and five studies had an overall WOE rating of L.

Table 2 Weight of evidence awarded to each study in the current systematic review

L, low; M, medium; H, high.

The core narrative themes extracted from the papers are presented under the following headings: (i) adequacy of CFP and (ii) factors influencing CFP. The former is categorized further into dietary diversity, meal frequency, timing of introducing CF and advice providers.

Adequacy of complementary feeding

As per the WHO IYCF indicators, adequacy of CFP is assessed according to dietary diversity, meal frequency and timing of introducing CFP. These are detailed in the subsections below with a further subsection discussing advice providers.

Dietary diversity

Dietary diversity was measured in some form in fourteen studies. Rates of achieved MDD varied throughout studies but were generally low, with MDD achieved by between 6 and 33 % of infants in eight studies that reported this outcome for 6–23-month-olds( Reference Aruldas, Khan and Hazra 26 – Reference Khan, Kayina and Agrawal 33 ). In de Onis (WOE=M), infants were fed a mean of 2·8 food groups at 6 months, rising to 5·1 at 24 months( Reference de Onis 34 ). Five other studies reported some information on diversity( Reference D’Alimonte, Deshmukh and Jayaraman 35 – Reference Lohia and Udipi 39 ).

Table 3 denotes a summary of all complementary food groups identified from the studies, categorized according to the WHO IYCF food groups defined above. Foods utilized for CF were identified in fifty-three included studies, of which nine had overall WOE=H and forty-four had overall WOE=M.

Table 3 Foods utilized for complementary feeding in India, categorized into WHO food groups

Thirty-one studies identified ‘grains, roots and tubers’ being used for CFP. Legumes and nuts were used in twenty-nine, and twenty-six studies identified ‘dairy products’ (e.g. milk, cheese, yoghurt) being used. In contrast, ‘eggs’ were identified in twelve studies, ‘flesh foods’ (e.g. meat, fish, poultry and liver/organ meats)’ in ten studies, ‘vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables’ in eight studies and ‘other fruits and vegetables’ in twenty-two studies.

Bentley et al. (WOE=H) found that grains were consumed by 63·8 % of infants in the past 24 h( Reference Bentley, Das and Alcock 27 ). In Fazilli et al. (WOE=M), Neog and Baruah (WOE=M) and Meshram et al. (WOE=H), cereals were also widely used( Reference Fazilli, Imtiyaz and Iqbal 40 – Reference Meshram, Laxmaiah and Venkaiah 42 ). In Katara et al. (WOE=M), cereals were the most frequently used food group, by 96 % of infants( Reference Katara, Patel and Kantharia 37 ). In contrast, in Kapur et al. (WOE=M) cereal intake in an urban slum in Delhi was noted as grossly inadequate( Reference Kapur, Sharma and Agarwal 43 ). Ragi, a traditional Indian grain, was identified in four studies as a common cereal type utilized in South India( Reference Pasricha, Shet and JFF 44 – Reference Sharan, Kumari and Nagabhushanam 47 ).

The use of ‘other fruits and vegetables’, namely fruits and vegetables not specified as vitamin A-rich, varied across India, from 95·4 % among study populations in rural Andhra Pradesh to 1·45 % in Uttarakhand when given alone( Reference Meshram, Laxmaiah and Venkaiah 42 , Reference Vyas, Kandpal and Semwal 48 ). Interestingly, in Garg and Chadha (WOE=M) in rural India, fruits and vegetables were excluded from an infant’s diet despite being part of the family diet due to beliefs that infants could not tolerate spice-cooked fruits and vegetables( Reference Garg and Chadha 36 ). In Vyas et al. (WOE=M), seasonal fruits such as guava and citrus were introduced before the addition of staples (e.g. cereals, rice), with gross undernutrition noted in the study population( Reference Vyas, Kandpal and Semwal 48 ).

In the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study, less than 11 % of children were noted to consume flesh foods( Reference de Onis 34 ). In an affluent Delhi district, Bhandari et al. (WOE=M) found that only 2·4 % of infants consumed non-vegetarian foods despite 57·5 % of their families being non-vegetarian( Reference Bhandari, Bahl and Taneja 49 ). Consumption of Fe-rich or Fe-fortified foods (e.g. flesh foods) was poorly reported. Kapur et al. (WOE=M) found that children consumed only 46 % of the RDA for Fe in their diets, and Pashricha et al. (WOE=M) found that delayed CF increased the risk of low dietary Fe intake( Reference Kapur, Sharma and Agarwal 43 , Reference Pasricha, Shet and JFF 44 ). Bentley et al. (WOE=H) found that 15 % of 6–23-month-olds consumed Fe-rich foods, which is similar to the 12·1 % reported by Aguayo et al. (WOE=H)( Reference Bentley, Das and Alcock 27 , Reference Aguayo, Nair and Badgaiyan 50 ).

Regarding commercial complementary foods, Sharan et al. (WOE=M) and Samuel et al. (WOE=H) noted use of commercial foods( Reference Sharan, Kumari and Nagabhushanam 47 , Reference Samuel, Thomas and Bhat 51 ). Cerelac was the most frequently mentioned commercial food( Reference Neog and Baruah 41 , Reference Ananda Kumar, Rangaswamy and Viswanatha Kumar 46 , Reference Lingam, Gupta and Zafar 52 – Reference Narayanappa, Ranganath and Gowda 54 ). Additionally, Ananda Kumar et al. (WOE=M), Lingam et al. (WOE=H) and Chhabra et al. (WOE=M) mentioned Farex, and Narayanappa et al. mentioned Nestum( Reference Ananda Kumar, Rangaswamy and Viswanatha Kumar 46 , Reference Lingam, Gupta and Zafar 52 – Reference Narayanappa, Ranganath and Gowda 54 ). Chhabra et al. also mentioned Nutramul( Reference Chhabra, Subhashini and Verma 53 ). In Sharan et al. only 15 % of infants were given commercial complementary food, with use concentrated among the highest socio-economic group( Reference Sharan, Kumari and Nagabhushanam 47 ), in keeping with Lingam et al. (WOE=H) who noted higher utilization rates in urban compared with rural areas( Reference Lingam, Gupta and Zafar 52 ).

Generally, micronutrient intake was not discussed in the included studies. In Pasricha et al. (WOE=M), 66 % of children were found to be deficient in at least one micronutrient, with micronutrient deficiencies particularly common in those who breast-fed longer( Reference Pasricha, Shet and JFF 44 ). The high use of grains and legumes by included infants may be beneficial, as Menon et al. found that intakes of these foods were associated with positive anthropometric outcomes relative to higher-nutrient foods like eggs or flesh foods( Reference Menon, Bamezai and Subandoro 29 ).

Meal frequency

Meal frequency was explored in twenty-one studies( Reference Aruldas, Khan and Hazra 26 , Reference Bentley, Das and Alcock 27 , Reference Mukhopadhyay, Sinhababu and Saren 30 , Reference Patel, Pusdekar and Badhoniya 31 , Reference Khan, Kayina and Agrawal 33 , Reference de Onis 34 , Reference Garg and Chadha 36 – Reference Lohia and Udipi 39 , Reference Meshram, Laxmaiah and Venkaiah 42 , Reference Ananda Kumar, Rangaswamy and Viswanatha Kumar 46 , Reference Aguayo, Nair and Badgaiyan 50 , Reference Samuel, Thomas and Bhat 51 , Reference Collison, Kekre and Verma 55 – Reference Saxena and Kumar 61 ). In ten studies, MMF was attained by between 25 and 50 % of the study population( Reference Bentley, Das and Alcock 27 , Reference Patel, Pusdekar and Badhoniya 31 , Reference Khan, Kayina and Agrawal 33 , Reference Katara, Patel and Kantharia 37 , Reference Malhotra 38 , Reference Ananda Kumar, Rangaswamy and Viswanatha Kumar 46 , Reference Aggarwal, Verma and Faridi 57 – Reference Kuriakose 59 , Reference Saxena and Kumar 61 ). In contrast, between 50 and 96 % of the population achieved MMF in seven studies( Reference Aruldas, Khan and Hazra 26 , Reference Mukhopadhyay, Sinhababu and Saren 30 , Reference Garg and Chadha 36 , Reference Lohia and Udipi 39 , Reference Meshram, Laxmaiah and Venkaiah 42 , Reference Aguayo, Nair and Badgaiyan 50 , Reference Yasmin 60 ). Seven included studies had overall WOE=H and fourteen had overall WOE=M.

Senarath et al. (WOE=H) noted that the rate of MMF was 42 % in children aged 6–23 months( Reference Senarath, Agho and Akram 32 ). Patel et al. (WOE=H) and Khan et al. (WOE=M) observed MMF in 41·5 and 48·6 % of children, respectively( Reference Patel, Pusdekar and Badhoniya 31 , Reference Khan, Kayina and Agrawal 33 ). In contrast, Chandwani et al. (WOE=M) noted that 96 % of breast-fed children were fed at least the minimum number of times recommended( Reference Chandwani, Prajapati and Rana 28 ).

Malhotra (WOE=M) noted a correlation between education and meal frequency in infants aged 9–18 months( Reference Malhotra 38 ). Finally, Lohia and Udipi (WOE=M) noted that male infants tended to have a higher feeding frequency than female infants( Reference Lohia and Udipi 39 ).

Timing of introducing complementary feeding

Table 4 denotes a summary of timing when CF was most commonly introduced across the fifty-nine included studies that investigated timing. The most common age for the introduction of CF was between 6 and 9 months (twenty-nine studies), followed by 3 to 6 months (twenty-two studies). Four studies noted that CF was started between 9 and 12 months for the majority of infants, while one study noted that CF was started at an age younger than 3 months for most infants. Twelve studies had overall WOE=H and forty-seven had overall WOE=M.

Table 4 Timing of introduction of complementary feeding in India

CF was noted to be delayed among children particularly in central and eastern India( Reference Padmadas, Hutter and Willekens 62 ). Inappropriate timing of initiation of CF was noted in both urban and rural regions of India, with timely CF achieved by as low as 3·5 % and as late as over 1 year of age( Reference Sharan, Kumari and Nagabhushanam 47 , Reference Bhandari, Bahl and Taneja 49 , Reference Roy, Dasgupta and Pal 56 , Reference Caleyachetty, Krishnaveni and Veena 63 ). In ten out of fifteen studies in urban areas, the majority of children started CF at 6–9 months( Reference Bentley, Das and Alcock 27 , Reference Khan, Kayina and Agrawal 33 , Reference Katara, Patel and Kantharia 37 , Reference Aguayo, Nair and Badgaiyan 50 , Reference Chhabra, Subhashini and Verma 53 , Reference Collison, Kekre and Verma 55 , Reference Roy, Dasgupta and Pal 56 , Reference Sreedhara and Banapurmath 65 , Reference Rao, Swathi and Unnikrishnan 80 , Reference Sinhababu, Mukhopadhyay and Panja 84 ). Eight out of eighteen studies in rural areas noted that CF started during 6–9 months of age( Reference Aruldas, Khan and Hazra 26 , Reference Chandwani, Prajapati and Rana 28 , Reference Meshram, Laxmaiah and Venkaiah 42 , Reference Vyas, Kandpal and Semwal 48 , Reference Lingam, Gupta and Zafar 52 , Reference Saxena and Kumar 61 , Reference Jayant, Purushottam and Deepak 67 , Reference Meshram, Kodavanti and Chitty 69 ), and seven out of eighteen noted that CF initiated at 3–6 months( Reference Rangaswamy, Kumar and Kumar 45 , Reference Narayanappa, Ranganath and Gowda 54 , Reference Caleyachetty, Krishnaveni and Veena 63 , Reference Farzani and Devi 68 , Reference Verma and Gupta 71 , Reference Damayanthi, Jayanth Kumar and Sridevi 72 , Reference Shroff, Griffiths and Suchindran 74 ).

In addition, Yasmin (WOE=M) noted that CF was initiated as early as 1 week( Reference Yasmin 60 ). However, in Mukhopadhyay et al. (WOE=M), CF timing was noted to be inappropriately early in 12·5 % of the study population in West Bengal slums( Reference Mukhopadhyay, Sinhababu and Saren 30 ). Similar findings were also noted in Goswami et al. (WOE=M), where only 13·2 % of the infants were introduced to CF at the age of 4–6 months( Reference Goswami, Dash and Dash 76 ), and in Roy et al. (WOE=M) in an urban slum in Kolkata where 72 % of infants were given CF at 6 months( Reference Roy, Dasgupta and Pal 56 ).

Sources of advice for feeding

Twenty-seven studies described advice providers for CFP, of which nine had overall WOE=H and eighteen had overall WOE=M. The commonest source of feeding advice were health-care professionals, including doctors, auxillary nurse midwives, lady health visitors and anganwadi health workers, usually at antenatal visits or during immunizations (twenty-one studies( Reference Aruldas, Khan and Hazra 26 , Reference D’Alimonte, Deshmukh and Jayaraman 35 , Reference Malhotra 38 , Reference Rangaswamy, Kumar and Kumar 45 , Reference Ananda Kumar, Rangaswamy and Viswanatha Kumar 46 , Reference Aguayo, Nair and Badgaiyan 50 , Reference Samuel, Thomas and Bhat 51 , Reference Chhabra, Subhashini and Verma 53 – Reference Aggarwal, Verma and Faridi 57 , Reference Yasmin 60 , Reference Saxena and Kumar 61 , Reference Bhanderi and Choudhary 64 , Reference Bagul and Supare 66 , Reference Farzani and Devi 68 , Reference Saxena and Kumari 77 – Reference Rao, Swathi and Unnikrishnan 80 )). The next most common source of advice was a family member, usually the grandmother or mother-in-law (eleven studies( Reference Aruldas, Khan and Hazra 26 , Reference D’Alimonte, Deshmukh and Jayaraman 35 , Reference Rangaswamy, Kumar and Kumar 45 , Reference Ananda Kumar, Rangaswamy and Viswanatha Kumar 46 , Reference Vyas, Kandpal and Semwal 48 , Reference Lingam, Gupta and Zafar 52 , Reference Narayanappa, Ranganath and Gowda 54 , Reference Collison, Kekre and Verma 55 , Reference Yasmin 60 , Reference Jayant, Purushottam and Deepak 67 , Reference Subbiah and Jeganathan 81 )), with nine further studies specifically mentioning elders( Reference D’Alimonte, Deshmukh and Jayaraman 35 , Reference Fazilli, Imtiyaz and Iqbal 40 , Reference Meshram, Laxmaiah and Venkaiah 42 , Reference Rangaswamy, Kumar and Kumar 45 , Reference Samuel, Thomas and Bhat 51 , Reference Saxena and Kumar 61 , Reference Bagul and Supare 66 , Reference Saxena and Kumari 77 , Reference Mayuri, Garg and Mukherji 79 ). Further sources of feeding advice were the media (four studies( Reference Patel, Pusdekar and Badhoniya 31 , Reference D’Alimonte, Deshmukh and Jayaraman 35 , Reference Malhotra 38 , Reference Rangaswamy, Kumar and Kumar 45 )) and friends (three studies( Reference Rangaswamy, Kumar and Kumar 45 , Reference Roy, Dasgupta and Pal 56 , Reference Yasmin 60 )).

Factors associated with complementary feeding practices

We identified numerous factors that influenced CFP. These are summarized in Table 5 as either a barrier or a promoter, and sub-categorized as acting at either family or organizational level. Due to conflicting study findings, factors may appear as both a barrier and a promoter. Twenty-four promoters and thirty barriers influencing CFP were identified. Promoters and barriers were further divided into factors influencing at the family and organizational level. In total, fifty-five studies identified factors associated with CF practices, of which twelve had overall WOE=H and forty-three had overall WOE=M.

Table 5 Factors influencing complementary feeding practices (CFP) in India

Barriers

Thirty-five studies identified barriers at the organizational level. Barriers were: cultural influences, employment, food insecurity, gender, inadequate antenatal care, lack of knowledge on optimal CFP, lack of media exposure, lack of parental education, location: Northern India and West India, focus on disability, low literacy, poor sanitation, poverty, birth in a public hospital and price of food. The most commonly cited barrier at the organizational level was cultural influences( Reference Fazilli, Imtiyaz and Iqbal 40 , Reference Neog and Baruah 41 , Reference Rangaswamy, Kumar and Kumar 45 , Reference Vyas, Kandpal and Semwal 48 , Reference Samuel, Thomas and Bhat 51 , Reference Chhabra, Subhashini and Verma 53 , Reference Collison, Kekre and Verma 55 , Reference Aggarwal, Verma and Faridi 57 , Reference Saxena and Kumar 61 , Reference Bhanderi and Choudhary 64 , Reference Shroff, Griffiths and Suchindran 74 , Reference Saxena and Kumari 77 – Reference Mayuri, Garg and Mukherji 79 , Reference Sharma and Sharma 82 ). Infant feeding practices in India appear to be strongly influenced by elderly women such as the mother-in-law( Reference Vyas, Kandpal and Semwal 48 , Reference Jayant, Purushottam and Deepak 67 ).

Thirty-one studies identified barriers at the family level. Barriers were: caesarean section, child’s age, concern about weight gain, crying infant, difficulty feeding child, inadequate breast milk production, lack of support, maternal age, maternal nutrition status, mothers from joint families, recent illness, religion, siblings, subsequent pregnancy and primiparity. The most commonly cited barriers at the family level were lack of knowledge on optimal CFP( Reference Aruldas, Khan and Hazra 26 , Reference Fazilli, Imtiyaz and Iqbal 40 , Reference Vyas, Kandpal and Semwal 48 , Reference Chhabra, Subhashini and Verma 53 , Reference Saxena and Kumar 61 , Reference Jayant, Purushottam and Deepak 67 , Reference Saxena and Kumari 77 , Reference Subbiah and Jeganathan 81 – Reference Yousafzai, Pagedar and Wirz 85 ) and inadequate breast milk production( Reference Rangaswamy, Kumar and Kumar 45 , Reference Sharan, Kumari and Nagabhushanam 47 , Reference Narayanappa, Ranganath and Gowda 54 , Reference Yasmin 60 , Reference Saxena and Kumar 61 , Reference Tyagi and Bhan 75 , Reference Saxena and Kumari 77 ).

Promoters

Thirty-two studies identified promoters at the organizational level. Promoters were: advice from a health-care professional, birth within a government institute, certain caste or tribe, education of parent, effective antenatal care, family support, Hindu mothers, literacy status of mother, location: north-eastern, southern or western, media exposure, social support group, socio-economic status, support system at work and wealth. The most commonly cited promoters at the organizational level were education of parent( Reference Aruldas, Khan and Hazra 26 , Reference Menon, Bamezai and Subandoro 29 , Reference Patel, Pusdekar and Badhoniya 31 , Reference Garg and Chadha 36 , Reference Lohia and Udipi 39 , Reference Neog and Baruah 41 , Reference Meshram, Laxmaiah and Venkaiah 42 , Reference Pasricha, Shet and JFF 44 , Reference Vyas, Kandpal and Semwal 48 , Reference Caleyachetty, Krishnaveni and Veena 63 , Reference Bhanderi and Choudhary 64 , Reference Farzani and Devi 68 , Reference Pathi, Das and Rasania 73 ), literacy status of mother( Reference Katara, Patel and Kantharia 37 , Reference Bagul and Supare 66 , Reference Farzani and Devi 68 , Reference Damayanthi, Jayanth Kumar and Sridevi 72 , Reference Rao, Swathi and Unnikrishnan 80 , Reference Dahiya and Sehgal 86 ) and wealth( Reference Aruldas, Khan and Hazra 26 , Reference Garg and Chadha 36 , Reference Lingam, Gupta and Zafar 52 , Reference Chhabra and Gupta 87 , Reference Veena, Krishnaveni and Srinivasan 88 ).

Twelve studies identified promoters at the family level. Promoters were: acknowledged importance of maternal health, advice seeking, autonomy of mother, BMI of mother, delivery with doctor present, high birth order, knowledge of optimal CFP, mother who works from home, older age at marriage and valuing nutrition. The most commonly cited promoter at the family level was knowledge of optimal CF( Reference D’Alimonte, Deshmukh and Jayaraman 35 , Reference Roy, Dasgupta and Pal 56 , Reference Jayant, Purushottam and Deepak 67 , Reference Padhy and Choudhury 78 ).

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present is the first systematic review to assess CFP in India. We identified that in many SA families in India, WHO IYCF standards on minimum dietary diversity, meal frequency and timing of introducing CF were not being met.

Implications of key findings

Legumes, rice, wheat and cereals appear to be the mainstay of complementary foods in Southern India. While this is in keeping with other low- and middle-income countries, these foods have low nutrient density and mineral bioavailability, and the use of other food groups is essential to satisfy the nutrient and mineral requirements of infants( Reference Erdman 89 ). Consumption of dietary Fe was infrequently mentioned except in the context of flesh foods, and was inadequate, considering that Fe has such an important role in infant health( Reference Kapur, Sharma and Agarwal 43 , Reference Pasricha, Shet and JFF 44 ).

Dietary diversity was found to be inadequate in almost all groups studied, with MDD achieved in only 6 to 33 % of 6–23-month-olds. Some have argued for use of media sources to influence this, with further research and interventions needed( Reference Lohia and Udipi 39 ).

It was found that MMF was not met by the majority of the populations sampled. Educational interventions may be useful to improve MMF going forward; Collison et al. found that frequency of feeds increased when families were given a feeding toolkit( Reference Collison, Kekre and Verma 55 ). In a previous review, educational interventions were also shown to be effective(90). Further research is required to uncover why MMF is so rarely met by caregivers.

The majority of studies found that CF was started during months 6–9 of life, with most studies noting limited maternal awareness on recommended CFP. By improving antenatal care and education on caring for an infant alongside decreasing barriers faced by mothers when restarting employment, optimal timing of CF may improve. Mass communication using ICT and mobile apps is a strategy that has been advocated by the Ministry of Women and Child Development( 92 ), and could be used to disseminate information on this topic.

Of the studies that identified sources of feeding advice, health-care professionals were the most commonly cited. Antenatal check-ups especially were a popular time for feeding advice to be given to mothers by health-care professionals( Reference Patel, Pusdekar and Badhoniya 31 , Reference Senarath, Agho and Akram 32 , Reference Malhotra 38 , Reference Rasania and Sachdev 58 , Reference Goswami, Dash and Dash 76 , Reference Sinhababu, Mukhopadhyay and Panja 84 ). Family members, particularly a mother-in-law or grandmother, were also very commonly cited sources of feeding advice. However, the advice given by them is often inappropriate. Saxena and Kumar noted that some female elders insisted mothers only started CF after 1 year( Reference Saxena and Kumar 61 ). There is a suggestion that family members can adversely influence mothers through conveying traditional beliefs, for example that colostrum is ‘dirty’, and that children cannot tolerate animal-based proteins until 18 months of age( Reference Rangaswamy, Kumar and Kumar 45 , Reference Collison, Kekre and Verma 55 , Reference Jayant, Purushottam and Deepak 67 ). Similar advice may also be conveyed by friends and peer groups. Media, including radio, newspapers and magazines, was an important but less commonly cited source of advice. Malhotra found that increased frequency of listening to the radio or of reading newspapers and magazines carried an increased likelihood of mothers having better feeding practices( Reference Malhotra 38 ).

Several studies identified cultural norms introduced by female elders that are barriers to appropriate CFP, such as preferential treatment of male infants. It is therefore key that opinion leaders are equally targeted in any intervention to improve CFP in communities. Studies by Senarath et al.( Reference Senarath, Agho and Akram 32 ) and Dewey and Brown( Reference Dewey and Brown 93 ) noted the effectiveness of systematic, participatory and coordinated approaches to improve CFP through peers and community facilitators, in keeping with UNICEF guidance on applying best practices and design in interventions( Reference Rogers 94 ).

We hope our identification of barriers and promoters will provide inspiration for further interventions to improve CFP. Existing interventions in India have been educational in nature, including counselling( Reference Bhandari, Mazumder and Bahl 95 ), resulting in increased energy intake and length; and education in complementary and responsive feeding( Reference Vazir, Engle and Balakrishna 96 ), resulting in increased energy intake and reduced stunting. The Lancet 2008 series on maternal and child nutrition included a piece on successful interventions across countries( Reference Bhutta, Ahmed and Black 97 ).

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our systematic review are derived by searching a large number of databases utilizing very broad search strings, performing an updated search in June 2016, and having two reviewers undertake study selection, data extraction and quality assessment.

Key limitations include exclusion of: (i) papers which focused solely on children over 2 years of age, where CFP described in their younger years may have been missed; (ii) papers published before the year 2000 at full-text review; and (iii) papers not published in English, which would have added to the diversity of CFP described.

In several studies where there was overlap between children under and over 2 years and/or SA by Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi origin, CFP described and attributed to the whole study population may be incorrect. Furthermore, we did not assess the quantities of the foods used, only the frequency with which they appeared in the studies.

While we excluded interventional studies that may have described CFP in their study population, this is unlikely to be the primary focus of such studies and therefore unlikely to have affected our systematic review significantly. Additionally, if we had included strict exclusion criteria for study design, this may have meant there was less of a need to exclude studies due to low overall WOE rating; however, on the other hand, we may have missed some useful studies by being more prescriptive.

Regarding bias, while we attempted to contact numerous authors to identify relevant grey literature for our review, due to the breadth and depth of the field of nutritional research, this is unlikely to have been exhaustive and publication bias is likely to be present. Additionally, the vast majority of studies (n 64) were cross-sectional, commonly using recall methods, with only seven cohort studies. This may mean reported results are biased towards time points when it is convenient to collect single sets of data, such as during medical visits.

Conclusion

Despite adoption of the WHO IYCF guidelines, inadequate CFP remain in SA communities across India. While India has made giant strides in decreasing child mortality over the last two decades, more must be done to improve CFP to further this aim. The present systematic review has highlighted CFP and the factors that influence them, providing knowledge of current behaviours; we recommend this information be used for context-tailored interventions that can be assessed and adopted according to their achievements.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Jia Ying Kuah, Anika Sharmila, Lucy Stephenson, Melanie Flury, Taimur Shafi, Atul Singhal, Rani Chowdhary, Charlotte Hamlyn-Williams, Prerna Bhasin and Conor Fee for assisting in the systematic review. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. L.M. is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Doctoral Research Fellowship (grant number DRF-2014-07-005); S.A. is funded by the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) North Thames at Bart’s Health NHS Trust; and M.L. is partly supported by the NIHR CLAHRC North Thames at Bart’s Health NHS Trust. NIHR had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Authorship: L.M., R.L. and M.L. conceived and participated in the design of the study. L.M., A.P., A.D., C.M., A.R., A.L. and S.A. coordinated and undertook the review. All authors performed the data interpretation and contributed equally to write the draft, read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.