High vegetable intake has been convincingly inversely related with risk of heart disease and stroke, possibly several cancers( Reference Boeing, Bechthold and Bub 1 ), and possibly obesity in adults( Reference Ledoux, Hingle and Baranowski 2 ). Vegetable intake tracks from the earliest years( Reference Resnicow, Smith and Baranowski 3 ), supporting the likelihood that the preference for( Reference Birch 4 ) and habit of vegetable intake is established early in life, even as early as the pre-school years( Reference Kudlova and Schneidrova 5 ).

Parents are believed to be an important influence on children’s dietary intake, especially in the pre-school years( Reference O’Connor, Watson and Hughes 6 ). However, many parents of pre-schoolers report difficulties in getting their child to eat vegetables( Reference Cullen, Baranowski and Rittenberry 7 ), suggesting these parents use ineffective practices in dealing with their child’s dietary behaviour. Ineffective parenting practices have been related to child obesity( Reference Morawska and West 8 ). Food-related parenting practices (i.e. parent behaviours intended to influence child food intake) have been broadly conceptualized into three categories: structure, demandingness (control) and warmth (responsiveness)( Reference Hughes, O’Connor and Power 9 ), and as effective or ineffective practices within those categories( Reference O’Connor, Watson and Hughes 6 ). A best-fitting model to parent-reported parenting practices to get their child to eat vegetables confirmed the three-dimensional structure, but revealed the effective and ineffective practices were loaded independently in separate structures( Reference Baranowski, Chen and O’Connor 10 ). Thus, parents appear to employ both effective and ineffective vegetable parenting practices. Vegetable parenting training may have to target reducing ineffective vegetable parenting practices, as well as increasing effective vegetable parenting practices. Understanding the influences on effective vegetable parenting practices (CS Diep, A Beltran, T-A Chen et al., unpublished results) will not elucidate the influences on ineffective vegetable parenting practices, for the purposes of designing such interventions.

Learning more effective ways of behaving often requires unlearning ineffective behaviours( Reference French, Green and O’Connor 11 ). Programmes to reduce ineffective vegetable parenting practices would benefit from an understanding of why parents employ them. Much of the existing research predicting parenting practices has focused on psychopathological or sociological factors. For example, stress and depression predicted impaired parenting, while perceived social support predicted improved parenting( Reference Harwood and Eyberg 12 ). Higher levels of maternal education were associated with mother’s higher use of controlling and lower use of emotional feeding practices( Reference Saxton, Carnell and van Jaarsveld 13 ). Mother’s parenting satisfaction was associated with lower pressure on the child to eat and lower food restriction( Reference Mitchell, Brennan and Hayes 14 ).

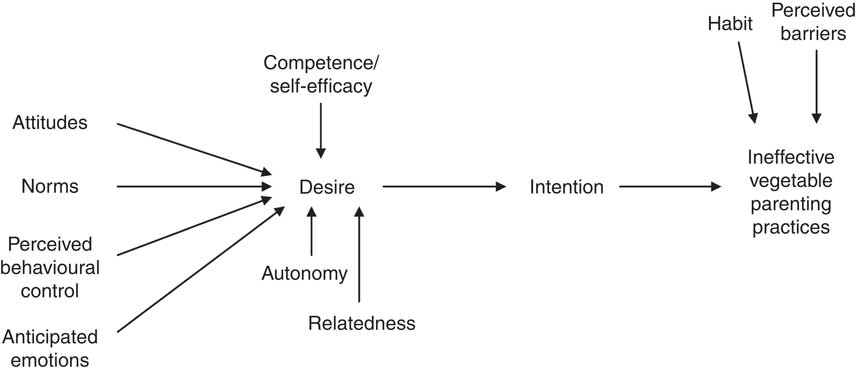

Alternatively, behaviour change programmes have generally been predicated on cognitive models of why people employ behaviours( Reference Baranowski, Cullen and Nicklas 15 ). Parent self-efficacy scales were developed for parent modelling of fruit, juice and vegetable intake; parent planning and encouraging child fruit, juice and vegetable intake; and parent making fruit, juice and vegetables available and accessible at home( Reference Cullen, Baranowski and Rittenberry 7 ). Parent fruit, juice and vegetable planning self-efficacy was significantly related to parent meal planning (r=0·34, P<0·001), while parent fruit, juice and vegetable availability self-efficacy was significantly related to home fruit, juice and vegetable availability (r=0·41, P<0·001) and accessibility (r=0·24, P<0·05)( Reference Cullen, Baranowski and Rittenberry 7 ). Since dietary interventions based on these common models of behaviour had limited effects( Reference Summerbell, Waters and Edmunds 16 , Reference Hingle, O’Connor and Dave 17 ), an innovative broader base of more highly predictive causal variables was needed( Reference Baranowski 18 ). The Model of Goal Directed Behavior expanded the Theory of Planned Behavior, which is the currently most consistently predictive model of health-related behaviour( Reference McEachan, Conner and Taylor 19 ), by incorporating ‘anticipated emotions’ and inserting ‘desire’ (operationalized to embody ‘intrinsic motivation’) between the psychosocial predictors and intentions( Reference Bagozzi, Baumgartner and Pieters 20 , Reference Perugini and Bagozzi 21 ). Self Determination Theory constructs that contribute to intrinsic motivation (autonomy, competence, relatedness)( Reference Ryan and Deci 22 ) were added to the Model of Goal Directed Behavior, as were habit (i.e. automated behaviour)( Reference de Bruijn, Keer and Conner 23 ) and barriers( Reference Lytle, Varnell and Murray 24 ), to enhance predictiveness (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 A Model of Goal Directed Vegetable Parenting Practices

The present paper reports the creation of a model of ineffective vegetable parenting practices( Reference Baranowski, Chen and O’Connor 10 ) using validated scales from the Model of Goal Directed Vegetable Parenting Practices( Reference Baranowski, Beltran and Chen 25 ). To our knowledge, this is the first report of the predictiveness of composite ineffective vegetable parenting practices by a psychosocial model.

Methods

Sample recruitment

Inclusionary criteria were being the parent of a pre-school child (3–5 years old), able to read and write English, and having the child spend most of his/her time with the participating caregiver. An Internet survey was announced in a Children’s Nutrition Research Center newsletter distributed to 25 000 recipients; fliers were posted on participant volunteer billboards around the Texas Medical Center, public libraries and YMCA in Houston; personal emails were sent to the age-appropriate members in the Children’s Nutrition Research Center list of research volunteers; and the study was listed on the Baylor College of Medicine volunteer website. The Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the protocol (#H-23566) for the study. Given the low-risk nature of participation, informed consent was indicated by the participant selecting the ‘participate’ button. Detailed sample characteristics have been presented elsewhere( Reference Baranowski, Chen and O’Connor 10 ).

Measures

An Internet survey (SurveyMonkey 2012; SurveyMonkey, Palo Alto, CA, USA) obtained parent responses to the ineffective vegetable parenting practices and Model of Goal Directed Vegetable Parenting Practices items. Qualitative research generated items to populate scales within this comprehensive model( Reference Hingle, Beltran and O’Connor 26 ), and psychometric validation of the scales and subscales has been reported( Reference Baranowski, Chen and O’Connor 10 , Reference Baranowski, Beltran and Chen 25 ). Table 1 lists the means, standard deviations, numbers of items, possible ranges of scores and Cronbach’s α values for the scales and subscales in the present study. Tests of construct validity indicated most subscales were bivariately correlated with composite scales of either effective vegetable parenting practices or ineffective vegetable parenting practices( Reference Baranowski, Beltran and Chen 25 ). Ineffective vegetable parenting practices (fourteen items) were submitted to confirmatory factor analyses and shown to have acceptable model fit with a single second-order and three first-order factors( Reference Baranowski, Chen and O’Connor 10 ).

Table 1 Possible ranges, Cronbach’s α values, means and standard deviations for all variables in the models predicting components of ineffective vegetable parenting practices using variables from the Model of Goal Directed Vegetable Parenting Practices

Analyses

Models were analysed using block regression procedures with a composite ineffective vegetable parenting practices scale as the dependent variable. Block regression modelling started with demographic characteristics, then the four intention scales, one desire scale, three barriers scales, autonomy, two relatedness scales, two competence/self-efficacy scales, four habit scales, four anticipated emotion scales, three perceived behavioural control scales, three attitude scales and two subjective norm scales, in that order, in twelve separate blocks. Demographic variables were retained in all models; backward deletion was employed at the end of each block entry for subscales not related to the outcome by at least P<0·10. The final model deleted variables not related at P<0·05. Analyses were conducted using the statistical software package SAS version 9·3 (2011).

Results

Four hundred and six participants provided informed consent, entered the questionnaire website and initiated completing the questionnaire; sixteen participants were deleted because they did not have a 3–5-year-old child or the child did not spend most days with that parent or guardian. Complete data were obtained from 307 participants. Since the demographic questions were at the end of the survey, data were not available to compare the eighty-three participants who provided incomplete data, with the 307 who provided complete data. Almost 90 % of respondents (89·3 %) were female, but more children were male (53·1 %; Table 2). Most respondents were White (37·1 %), with representation from all major ethnic groups in Houston (19·5 % Black/African American, 10·1 % Hispanic, 31·6 % Other (including Asian) and 1·6 % missing). Over half the sample (64·5 %) had a college degree or more; over half (54·1 %) had an annual household income of $US 60 000 or higher.

Table 2 Sample demographic characteristics

GED, General Educational Development.

In the final model, compared with postgraduates, technical school graduates (standardized β=−0·145, P=0·003) were significantly less likely to use ineffective vegetable parenting practices with no other demographic characteristics related (Table 3). In contrast to what might be expected with the Theory of Planned Behavior, none of the intention variables were significantly related to ineffective vegetable parenting practices (Table 3). Variables significantly positively related to ineffective vegetable parenting practices in order of relationship strength included habit of controlling vegetable practices (standardized β=0·349, P=0·0001) and desire (standardized β=0·117, P=0·025). Variables significantly negatively related to ineffective vegetable parenting practices in order of relationship strength included perceived behavioural control of negative parenting practices (standardized β=−0·215, P=0·000), habit of active child involvement in vegetable selection (standardized β=−0·142, P=0·008), anticipated negative parent emotional response to child vegetable refusal (standardized β=−0·133, P=0·009), autonomy (standardized β=−0·118, P=0·014), attitude about negative effects of vegetables (standardized β=−0·118, P=0·015) and descriptive norms (standardized β=−0·103, P=0·032). The model accounted for 40·5 % of the variance in ineffective vegetable parenting practices use.

Table 3 Final model predicting ineffective vegetable parenting practices using block regression analyses with demographics and scales from a model of goal-directed self-determined vegetable parenting practices

β, standardized estimate; GED, General Educational Development.

Discussion

The available scales accounted for 40·5 % of the variance in the composite ineffective vegetable parenting practices, suggesting the model tapped constructs important in ineffective vegetable parenting practices use, even though some of these subscales had low internal consistency reliabilities (Table 1)( Reference Baranowski, Beltran and Chen 25 ).

Ineffective vegetable parenting practices were not inversely linearly related with household educational attainment or household income, as found in other studies( Reference Saxton, Carnell and van Jaarsveld 13 ). Not using ineffective vegetable parenting practices would be desirable, but why technical school graduates alone were less likely to use ineffective vegetable parenting practices, and not higher educational attainment groups, is not clear. Perhaps there is no clear public understanding of what constitutes ineffective vegetable parenting practices. Future research needs to clarify this issue.

The strongest relationship with ineffective vegetable parenting practices was the habit of controlling vegetable parenting practices (standardized β=0·349; subscale Cronbach’s α=0·68)( Reference Baranowski, Chen and O’Connor 10 ), i.e. the habit of using controlling parenting practices is the primary influence on use of ineffective vegetable parenting practices. The three habit items loaded most heavily on this subscale included automatically yelling at the child for not eating a vegetable, automatically keeping the child from going to play if he/she doesn’t eat his/her vegetable and automatically rewarding the child with sweets for eating a vegetable. Thus, ineffective habits strongly predicted ineffective behaviour.

The next strongest relationship with ineffective vegetable parenting practices was the perceived behavioural control of negative parenting practices (standardized β=−0·215), despite it having a low Cronbach’s α (α=0·54)( Reference Baranowski, Chen and O’Connor 10 ). Thus, the easier parents perceived it was to use these parenting practices, the more likely they were to use them. The three most heavily loaded items on this subscale included ease of getting the child to eat more vegetables by: insisting he/she stay seated at the table until he/she ate the vegetable, begging him/her to eat vegetables and making him/her feel guilty when he/she doesn’t eat vegetables.

The habit of active involvement of the child in vegetable selection was third most significantly inversely related to ineffective vegetable parenting practices (standardized β=−0·142). Parents who involved children in vegetable selection (an effective vegetable parenting practice) were less likely to engage in ineffective vegetable parenting practices. Both habit subscales operationalized the automaticity of the habit construct( Reference Verplanken and Orbell 27 ). Three other habit sub-constructs have recently been proposed: stimulus−response bonds, patterning of action and negative consequences for non-performance( Reference Grove and Zillich 28 ). Given the strong predictiveness of the automaticity sub-construct, future research should attempt to measure the other three habit sub-constructs.

The anticipated negative parent emotional response to child vegetable refusal was also inversely related to ineffective vegetable parenting practices (standardized β=−0·133). The three most heavily loaded items on this subscale included ‘If I served my child a new vegetable and they refused to eat it, I would feel: frustrated, …upset’ and ‘If I served my child a vegetable that they liked, and they refused to eat it, I would feel upset’. Thus, parents getting upset in response to child refusal of new or previously liked vegetables increased the likelihood of using ineffective vegetable parenting practices. Parent emotional responses to child food rejection are not well studied.

The autonomy subscale was inversely related to ineffective vegetable parenting practices (standardized β=−0·118). These items emphasized parent perceived personal choice in encouraging their child to eat vegetables, and as would be expected, were inversely related to ineffective vegetable parenting practices.

Perceived negative outcomes (i.e. attitude or negative outcome expectancy) of getting a child to eat vegetables was inversely related to ineffective vegetable parenting practices (standardized β=−0·118). The three most heavily loaded items on this subscale included ‘If my child started eating more vegetables on most days, my child would: be exposed to germs on the vegetables, …have more stomach problems, like diarrhea or gas, and …be exposed to unhealthy chemicals on vegetables’. This negative relationship would not be intuitively expected. It is possible that parents high on perceived negative outcomes would be less likely to use either ineffective or effective vegetable parenting practices.

Items on desire that identified the difficulties of encouraging a child to eat vegetables (i.e. ‘…is hard, …is frustrating’) were reverse coded so that higher scale scores reflected the enjoyable or rewarding aspects of doing so. Thus, the obtained positive relationship supports the notion that parents most likely to see encouraging vegetable intake as enjoyable were more likely to engage in ineffective vegetable parenting practices, suggesting that parents are not aware of a difference between effective and ineffective practices.

Finally, descriptive norms were inversely associated with ineffective vegetable parenting practices (standardized β=−0·103) despite the very low Cronbach’s α (α=0·13). The two items in this subscale included ‘Most parents try to get their child to eat more vegetables’ and ‘Most children eat enough vegetables’. Respondents scoring high on this subscale may believe they as parents have been successful at getting their child to eat enough vegetables and don’t believe they need to do more.

A diverse set of variables were related to ineffective vegetable parenting practices. Several variables not included in the Theory of Planned Behavior, but from the Model of Goal Directed Behavior (i.e. desire, negative parent response to child vegetable refusal) and Self Determination Theory (e.g. autonomy) were significantly related to ineffective vegetable parenting practices. This suggests that the Model of Goal Directed Vegetable Parenting Practices substantially extended the predictiveness of the Theory of Planned Behavior. These relationships need to be verified in larger, more ethnically and socio-economically diverse samples, and in longitudinal designs to support a causal interpretation of the relationships with ineffective vegetable parenting practices.

Parallel analyses were conducted predicting effective vegetable parenting practices (CS Diep, A Beltran, T-A Chen et al., unpublished results). Path analysis revealed these variables were mostly interrelated as would be expected (e.g. Fig. 1), although some of the paths were not significant (CS Diep, A Beltran, T-A Chen et al., unpublished results). The predictors of effective vegetable parenting practices varied from those of ineffective vegetable parenting practices. No demographic variables predicted effective vegetable parenting practices. Three habit variables (Habit of Active Child Involvement in Vegetable Selection, Habit of Positive Vegetable Environment and Habit of Positive Vegetable Communication) were the most significantly related, suggesting automaticity was also important for effective vegetable parenting practices. The Barrier of the Respondent Not Liking Vegetables was also significantly related, suggesting respondents compensated for their own vegetable dislike by employing more effective vegetable parenting practices. Finally, Behavioural Control of Positive Influence on Vegetable Consumption was inversely related to effective vegetable parenting practices. Thus, fewer and similar variables (habit, perceived control) were related to effective vegetable parenting practices and ineffective vegetable parenting practices.

A goal of intervention to increase effective vegetable parenting practices would be to reduce the use of ineffective vegetable parenting practices. Changes in the variables significantly related in these analyses should result in ineffective vegetable parenting practices change( Reference Baranowski 18 ). A hallmark of habit, the most strongly related variable, is the automaticity of the behaviour. A two-pronged habit intervention might both draw attention to and attempt to reduce the automatic use of ineffective vegetable parenting practices and increase the involvement of children in vegetable selection. Mindfulness training has met some success in countering ingrained automatic dietary habits( Reference Carmody, Olendzki and Merriam 29 ), and deserves testing in this context.

Reducing the perceived behavioural control, or ease of use, of ineffective vegetable parenting practices should reduce ineffective vegetable parenting practices. Change strategies might include some self-inhibition strategies (e.g. snapping a rubber band on one’s wrist when about to employ an ineffective vegetable parenting practice) or more cognitive interventions that persuade participants about the perceived costs of using ineffective vegetable parenting practices, e.g. the longer-term aversive health consequences of their child not eating enough vegetables.

Emotion variables have generally not been included in cognitive models of behaviour change( Reference Baranowski, Cullen and Nicklas 15 ), and few diet-related behaviour change interventions have explicitly addressed emotions. Emotion change, however, is a central construct in psychotherapy( Reference Greenberg 30 ) and 306 emotion regulation strategies have been identified( Reference Webb, Miles and Sheeran 31 ). Advocating moderation, instead of restraint, led to positive emotions and weight-related behaviour change( Reference Stotland 32 ), and should be tested.

Autonomy-enhancing activities have been shown to increase intrinsic motivation for change, and motivational interviewing has led to increased autonomy( Reference Patrick and Williams 33 ). Thus, motivational interviewing offers promise of change for these Model of Goal Directed Vegetable Parenting Practices components.

Attitudes have generally been operationalized as outcome expectancies( Reference Williams, Anderson and Winett 34 ). Outcome expectancies are amenable to change through group discussion( Reference Boivin, Polivy and Herman 35 ), which could be attempted with groups of parents.

Team-based interventions delivered by peers have been designed to change norms( Reference Moe, Elliot and Goldberg 36 ) and demonstrated to change vegetable intake( Reference Elliot, Goldberg and Kuehl 37 ). Norm change partially mediated dietary change( Reference Ranby, MacKinnon and Fairchild 38 ). Thus, teams of parents discussing parenting change offers promise of changing perceived descriptive norms and in turn parenting practices.

The strengths of the current research included use of a broad theoretical framework and validated indicators of the independent and dependent variables. Limitations included the cross-sectional design, modest sized sample, the self-reported nature of all variables, the mostly higher socio-economic status of families in the sample, and the time inconsistency in measurement between intentions and behaviour: intention variables predicted near future behaviours, but the parenting practices measured the recent past behaviour. No measures were available of child vegetable intake.

Further research is needed to assess: the predictiveness of future ineffective vegetable parenting practices by these scales in longitudinal samples; their utility in identifying and targeting components for reducing ineffective vegetable parenting practices in interventions; and their validity in assessing impact of ineffective vegetable parenting practices intervention programmes. Innovative interventions targeting the model-based constructs offer hope of reducing use of ineffective vegetable parenting practices, thereby leading to increased child lifelong vegetable intake.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This research was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant number HD058175) and institutional support from the US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service (Cooperative Agreement no. 58-6250-6001). The funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: T.B. was principal investigator for the overall project and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. A.B. was the project manager. T.-A.C. was the data manager and statistician. D.T., T.O. and S.H. contributed conceptually to the measures. C.D. participated in review of analyses. J.C.B. was the project coordinator. All authors reviewed, critiqued and approved this manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the protocol (#H-23566) for this study. Informed consent was indicated by the participant selecting the ‘participate’ button in the web-based survey.