There is increasing international interest in the causal role of nutrition and other dietary factors in the development of asthma and allergic diseases( Reference Nurmatov, Nwaru and Devereux 1 ). Currently asthma affects 300 million people worldwide( Reference Braman 2 ). Asthma and allergic manifestations are increasing, especially early in life, in both developed and developing countries( Reference Matsui and Matsui 3 ). To date, the main factors related to the development of asthma and allergic diseases have been identified as allergen exposure, pollutant exposure, endotoxin exposure, immunizations, diet, genetic predisposition and exposure to parasites and viruses( Reference Matsui and Matsui 3 ). It has also been hypothesized that these increases are a consequence of changing diet or nutrition status( Reference Nurmatov, Devereux and Sheikh 4 ). These exposures might act directly on the immune system or end organs to produce allergic reactions( Reference Nurmatov, Devereux and Sheikh 4 ). Several studies have measured anthropometric parameters at birth and examined their relationship with later incidence of allergic disease. A larger head circumference at birth was reported to be associated with increased risk of raised serum IgE level in children and adults( Reference Godfrey, Barker and Osmond 5 ), while low birth weight and prematurity have been linked to an increased risk of atopic dermatitis( Reference Olesen, Ellingsen and Olesen 6 ).

With respect to current nutritional status, obesity has been widely recognized to be more common among children with asthma, and associations between asthma and obesity have been observed in cross-sectional studies of both adults and children( Reference Okabe, Adachi and Itazawa 7 ). Previous studies reported that higher BMI and being overweight were risk factors for asthma/wheezing and allergic diseases in children from Japan, Taiwan and the UK, countries where childhood obesity is an increasing public health concern( Reference Okabe, Adachi and Itazawa 7 – Reference Figueroa-Munoz, Chinn and Rona 10 ). Little evidence exists, however, on the potential association between undernutrition and current wheezing/asthma and allergic diseases. In the current study, we examined the relationship between chronic undernutrition and current wheezing as an asthma symptom in Bangladesh, where levels of childhood undernutrition are among the highest in the world.

Methods and materials

Study area and population

The current cross-sectional study was nested within a large-scale randomized clinical trial of nutrition interventions in pregnancy: the Maternal and Infant Nutrition Intervention in Matlab (MINIMat) Trial( Reference Persson, Arifeen and Ekström 11 ) (trial registration: isrctn.org identifier ISRCTN16581394). Matlab is a rural region of Bangladesh, about 50 km south-east of the capital Dhaka( Reference Razzaque and Streatfield 12 ). The International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) has been running a health and demographic surveillance system in the area since 1966 that covers a population of about 220 000. Community health research workers visit every household on a monthly basis to update information on demographic events, such as marriage, pregnancy, birth, death, in-migration and out-migration, as well as to collect information on the morbidity of children below 5 years of age and women of childbearing age. Socio-economic information, including education and household assets, is also recorded by periodic censuses( Reference Razzaque and Streatfield 12 ).

Maternal and Infant Nutrition Intervention in Matlab Trial

Recruitment of the women in the MINIMat Trial( Reference Persson, Arifeen and Ekström 11 ) was conducted in the Matlab health and demographic surveillance system area of Bangladesh from November 2001 to October 2003. Food and micronutrient supplementation was continued until birth of their children. In brief, women were recruited early in pregnancy through regular surveillance of the demographic area covered by icddr,b. Consenting women were randomized to two separate nutritional interventions in pregnancy: (i) access to food supplementation or (ii) receipt of a micronutrient supplement. For the food intervention, women were randomized to receive encouragement to attend government-sponsored local community nutrition centres either early in pregnancy (8–10 weeks’ gestation) or at a time of their choosing (usually about 20 weeks’ gestation). Food supplements that provided energy 2544 kJ/d (608 kcal/d) and vegetable protein 18 g/d were available to all attending women. Women participating in the MINIMat Trial were also randomized to receive one of three micronutrient supplements with identical appearance: (i) 30 mg of iron and 400 μg of folate (Fe30F); (ii) 60 mg of iron and 400 μg of folate (Fe60F); or (iii) the combination of fifteen micronutrients called UNIMAP (UN multiple micronutrient preparation) at or above the recommended daily allowance, which also contained 30 mg of iron and 400 μg of folate (MMS).

Study participants and design

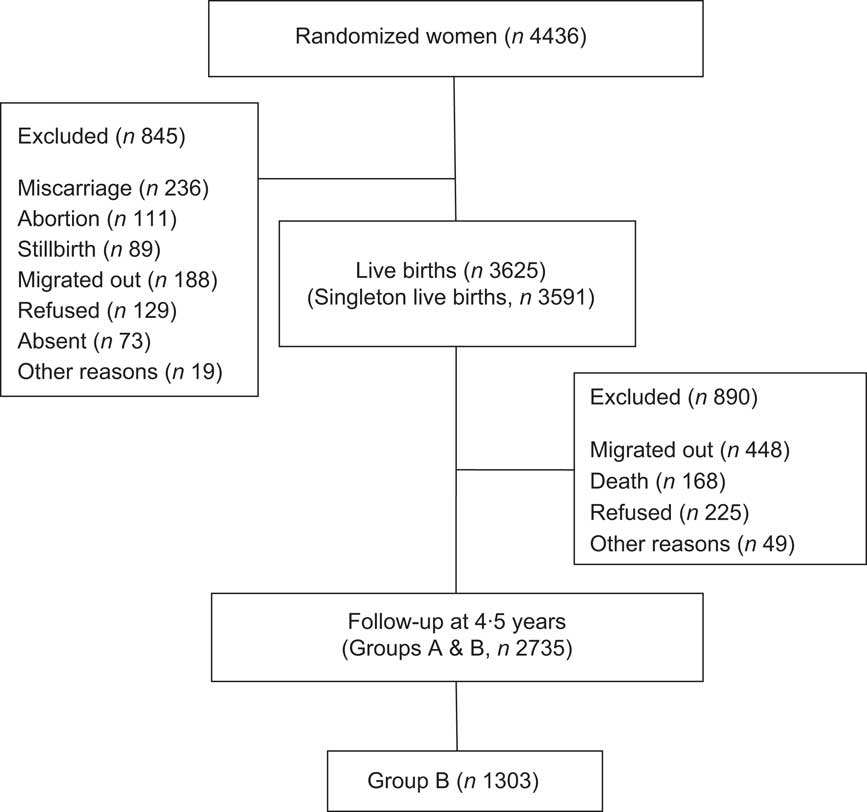

The 4436 mothers in MINIMat were followed during pregnancy when data on socio-economic status (SES) and morbidity of mothers were collected. Information about their children's gestational age, birth weight, birth length, head circumference and chest circumference were also collected at delivery. From these, a total of 3625 babies were born. The major reasons for exclusion were abortion (n 111), miscarriage (n 236), stillbirth (n 89) and out-migration (n 188). A total of 2735 children were eligible for a follow-up assessment when they reached 4·5 years of age, excluding out-migration (n 484), death (n 168), refused (n 225) and other reasons (n 49; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Flow chart of the study children

To reduce the burden from many examinations for one child in the multi-component 4·5-year follow-up study, these children were split into two groups according to the calendar year of birth (Group A, one calendar year, May 2002 to April 2003; Group B, one calendar year, May 2003 to April 2004). The study component of immunity, asthma and allergic diseases was included in the protocol using Group B children. Basic characteristics were not statistically different among groups in terms of age, sex and SES (data not shown).

Procedures

A 5 ml sample of venous blood was collected to measure total and specific IgE in serum. The serum samples were kept at −70°C until they were analysed. Total IgE was measured by human IgE quantitative ELISA kit (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., Montgomery, TX, USA). Specific IgE level against house dust mites (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus; DP) was measured by the CAP-FEIA system (Phadia AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Anti-DP IgE > 0·70 UA/ml was considered positive according to the information provided by the manufacturer. Fresh stools from the participants were collected in the morning for examination of parasite eggs by routine microscopy. Their immediate hypersensitivity reaction was tested by a skin prick test using mite allergen (DP) following standard procedures (Torii Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Skin reactions were recorded at 20 min as the average of the maximum weal diameters. A swelling size greater than 5 mm in diameter was considered positive.

Children's weight was measured to the nearest 100 g with a TANITA digital scale (Tanita Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with children wearing light clothes. Height was measured to the nearest 0·1 cm with a Holtain stadiometer (Holtain, Birmingham, UK). Stunting, wasting and underweight were calculated using the WHO Anthro program version 3·1·0. Stunting was defined as height-for-age Z-score <−2, wasting as weight-for-height Z-score <−2 and underweight as weight-for-age Z-score <−2. Mothers’ weight and height were measured in light clothes using standardized scales and a stadiometer and their BMI was calculated. These measurements were taken at the same time as their children's assessment at 4·5 years, as well as in early pregnancy at 8 weeks of gestation.

Current wheezing, ever wheezing and ever asthma were identified using the International Study on Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) questionnaire( Reference Leung, Wong and Lau 13 ). The written ISAAC questionnaires were translated into Bangla, the national and local language, following the ISSAC protocol. A trained expert in both Bangla and English translated the original ISSAC questionnaire. Then it was back-translated into English by another bilingual expert. The translated questionnaires were pretested and necessary modifications made before data collection. The ISSAC questionnaires were administered by trained interviewers.

Current wheezing was defined as wheezing symptoms in the past 12 months; ever wheezing was defined as wheezing symptoms at any point in the past; and ever asthma was defined as asthma symptoms at any point in the past.

SES was estimated using a wealth index based on information about household assets and principal component analysis of that, producing a weighted score( Reference Gwatkin, Rustein and Johnson 14 ). Scores were categorized into quintiles, with category one representing the poorest and category five the richest. Season of birth was categorized as pre-monsoon (January to May), monsoon (June to September) and post-monsoon (October to December).

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the research review committees and ethical review committees of both icddr,b and Uppsala University. Written informed consent was obtained from each child's legal guardian prior to participation in the study.

Statistical analysis

Data were categorized and analysed using the statistical software package IBM PASW Statistics version 20·0. The values of total and specific IgE were normalized by logarithmic transformation. Descriptive statistics were performed for age, sex, nutritional status, asthma and wheezing information, laboratory data, mother's parity, mother's BMI, SES and intervention trial arm during pregnancy( Reference Persson, Arifeen and Ekström 11 ). First, women were randomized into two food groups, early in pregnancy (8–10 weeks’ gestation) or at a time of their choosing. Each food group was again divided into three micronutrient categories (Fe30F, Fe60F and MMS), resulting in a total of six groups. Values were expressed as means, standard deviations and percentages. The χ 2 test was used to assess the association for categorical variables for current wheezing. Univariate logistic regression was performed to examine potential risk factors for current wheezing such as low birth weight, prematurity, stunting, wasting, underweight, allergic markers, family history of asthma and maternal BMI. Finally, multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed including the covariates for current wheezing identified by univariate analysis. Interactions were tested by using a cross-product term including stunting and food and micronutrient supplementation. The risks were estimated as odds ratios together with 95 % confidence intervals. Two-sided P values less than 0·05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

The age of the children at the time of enrolment for the present cross-sectional study ranged from 53·6 to 60·8 months (mean 54·4 (sd 0·72) months). Boys represented 52·6 % of the sample. Twenty-nine per cent of the children were born with low birth weight (<2500 g) and 13·9 % were premature (<37 weeks). Of the children, 31·7 % were stunted, 17·3 % were wasted and 40·7 % were underweight. A family history of asthma was present in 22·0 % of the children. Mean maternal BMI was 21·0 kg/m2 and 23·7 % had low BMI (<18·5 kg/m2). During the supplementation trial, mother's weight and height were also measured in early pregnancy at 8 weeks of gestation. Mean maternal BMI at early pregnancy was 23·1 kg/m2 and 26·4 % of mothers showed low BMI (<18·5 kg/m2; Table 1). Total IgE (geometric mean) was 526·44 IU/ml (range 172·93–3039·15 IU/ml). Positivity for serum anti-DP IgE was 44·3 %. The skin prick test with mite antigen showed that 15·7 % of the study children were positive. For Ascaris lumbricoids eggs in the stool 17·4 % were positive and for Trichuris trichura 17·5 % were positive (Table 2). Because some of the samples were not examined due to insufficient amount of blood during collection, we analysed 912 blood samples for total and specific IgE. We also assessed for any differences in characteristics between the children whose blood was analysed and those whose was not, and we found them to be similar in characteristics.

Table 1 Association between current wheezing and different parameters among rural Bangladeshi children (n 912) at age 4·5 years, MINIMat Trial, December 2007 to November 2008

MINIMat, Maternal and Infant Nutrition Intervention in Matlab; HAZ, height-for-age Z-score; WHZ, weight-for-height Z-score; WAZ, weight-for-age Z-score; DP, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (house dust mites).

Table 2 Geometric mean of serum total IgE and positivity of anti-DP IgE, mite antigen skin prick test and helminth eggs among rural Bangladeshi children (n 912) at age 4·5 years, MINIMat Trial, December 2007 to November 2008

DP, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (house dust mites); MINIMat, Maternal and Infant Nutrition Intervention in Matlab.

Nutritional status, wheezing and asthma

The overall incidence of current wheezing in the present study was 19·7 %, ever wheezing was 45·2 % and ever asthma was 18·0 %. Stunted children were more likely to have current wheezing compared with non-stunted children (P = 0·007). Underweight children also had a higher risk of current wheezing than non-underweight children (P = 0·046), but wasting did not show a significant relationship with current wheezing (P = 0·795). Among the other variables, family history of asthma was strongly associated with current wheezing (P < 0·001). Mother's BMI in early pregnancy was not significantly related with current wheezing (P = 0·403), but mother's current BMI was significantly associated with current wheezing (P = 0·037; Table 1). There was no influence of season of birth on current wheezing (pre-monsoon v. monsoon, P = 0·19; pre-monsoon v. post-monsoon, P = 0·17). Univariate logistic regression analysis revealed that the stunted children had 1·6 times increased risk of current wheezing compared with non-stunted children (OR = 1·58; 95 % CI 1·13, 2·22; Table 3). Underweight children were also at higher risk of current wheezing than non-underweight children (OR = 1·39; 95 % CI 1·00, 1·94), whereas wasted children did not show such a trend (OR = 0·94; 95 % CI 0·61, 1·46). We tested the relationship of current wheezing with stunting, wasting and underweight separately in multivariate models and present the results in Table 3. After adjustment for selected covariates in multivariate logistic regression analysis, stunting remained significantly associated with current wheezing (OR = 1·74; 95 % CI 1·19, 2·56). However, underweight became non-significant after adjustment (OR = 1·28; 95 % CI 0·89, 1·86; Table 3). Family history of asthma also remained significant in multivariate analysis (P < 0·001). Similarly, ever wheezing, ever asthma and atopic sensitization measured by anti-DP IgE were also tested both in univariate and multivariate analyses, but they were not significantly associated with any of the nutritional factors (P > 0·05). Furthermore, the relationships between current wheezing and atopic sensitization such as anti-DP IgE and the skin prick test were examined, but none was significant (P > 0·05). Current wheezing was not associated with birth outcome such as low birth weight, prematurity and birth length (P > 0·05). The study also analysed morbidity data for the last 2 weeks and found that current wheezing was related to other infections, such as cough and cold, and diarrhoea (P < 0·001).

Table 3 Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses with current wheezing as the dependent variable among rural Bangladeshi children (n 912) at age 4·5 years, MINIMat Trial, December 2007 to November 2008

MINIMat, Maternal and Infant Nutrition Intervention in Matlab.

Adjustment by sex, birth weight, birth length, gestational age at birth, mother's parity, maternal BMI, family history of asthma, socio-economic status, season of birth and intervention trial arm.

*Significant association: P < 0·05.

Low birth weight, prematurity and childhood malnutrition

Because we found a relationship between stunting and current wheezing, we examined whether stunting/underweight/wasting was related to low birth weight/prematurity. Birth characteristics were related to nutritional status at 1 year of age but were not related to nutritional status at 2 years and 4·5 years of age. Especially, stunting and underweight at 1 year were related to low birth weight (P < 0·001), prematurity (P < 0·001) and short birth length (P < 0·001). But stunting, wasting and underweight at 2 years and 4·5 years were not related to birth outcomes (P > 0·05).

Effects of prenatal intervention on current wheezing

We examined the effects of prenatal food and micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy( Reference Persson, Arifeen and Ekström 11 ) on current wheezing of the children. There was no difference in prevalence of current wheezing between early in pregnancy (8–10 weeks’ gestation) and at a time of their choosing (usually about 20 weeks’ gestation; P = 0·53), between the Fe60F group and the Fe30F group (P = 0·94) or between the MMS group and the Fe30F group (P = 0·87). We also examined the interactions for the combined effects of food and multiple micronutrients, but did not find any significant interaction terms (P > 0·05). After adjustment for intervention trial arm, the main effects of stunting on current wheezing still remained significant (P = 0·004).

Discussion

In the present study we found that the incidence of wheezing among children in rural Bangladesh was high and that stunting, an indication of long-term chronic malnutrition, was significantly associated with current wheezing in rural Bangladeshi children aged 4·5 years. In particular, the positive association of stunting with current wheezing remained after adjustment for selected covariates. According to UNICEF, 39 % of children <5 years of age in the developing world are stunted; the stunting rates are highest in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa( 15 ). A previous study in the same area suggested that wheezing is a significant cause of morbidity in rural Bangladeshi children( Reference Zaman, Takeuchi and Yunus 16 ), and there are a number of challenges to provide optimal management of childhood asthma in developing country settings( Reference Zar and Levin 17 ). A previous study has also shown that underweight children had lower lung function and lower body fat was associated with higher occurrence of asthma symptoms( Reference Berntsen, Lødrup Carlsen and Hageberg 18 ). Further it was reported that normal lung growth might be affected in malnourished children, leading to an increased likelihood of the occurrence of asthma symptoms( Reference Berntsen, Lødrup Carlsen and Hageberg 18 ). Our present study was in agreement with these findings, suggesting that malnutrition might be a significant risk factor for current wheezing in Bangladeshi children.

An earlier study suggested that there was a defective T-cell response in malnourished children and that the proportion of total B cells, and those bearing the low-affinity IgE receptor (CD23+), was increased in moderately malnourished children( Reference Hagel, Lynch and Puccio 19 ) and may cause increased specific IgE, which leads to wheezing and asthma symptoms. Another recent study mentioned that populations in low-income countries, particularly post-weaning children, are likely to have a deficient intake of long-chain PUFA, which might affect immune function( Reference Prentice and van der Merwe 20 ). A number of studies have drawn attention to the thymus as a potential mediator of the immunological consequences of undernutrition. The long-term consequences of early undernutrition for thymic development and function are not known, but the thymus has been hypothesized as a mediator of the associations between undernutrition and symptoms of atopic and autoimmune disease( Reference Thomas, Melinda and Kuzawa 21 ). However, the present study did not find any relationship between atopic sensitization and current wheezing, suggesting that wheezing in rural Bangladeshi children is mostly non-atopic, similar to a previous Latin American study in children and adolescents in underprivileged populations( Reference Pereira, Sly and Pitrez 22 ). The association between asthma and atopic sensitization increases with economic development, which is mostly evidenced in industrialized countries. In the ISAAC Phase II study, the population fraction of asthma attributable to atopy, measured by the skin prick test, was 41 % in affluent countries but only 20 % in non-affluent countries in children aged 8–12 years( Reference Weinmayr, Weiland and Björkstén 23 ). Moreover, in two Latin American study centres included in the ISAAC Phase II study (Pichincha Province, Ecuador and Uruguaiana, Brazil), only 11 % of asthma was attributable to the skin prick test, while a study of children of the same age living in rural Esmeraldas Province in Ecuador showed that only 2·4 % of asthma was attributable to the skin prick test( Reference Moncayo, Vaca and Oviedo 24 ). Therefore, our data indicate that undernutrition in the children of the present study may not trigger atopy but may influence the immune functions, leading to the development of wheezing symptoms.

Stunting is a chronic form of malnutrition and its causative factors are poorly understood. It may start from intra-uterine life and the peak incidence is before 2 years of life( Reference Ahmed, Ahmed and Roy 25 ). A recent review suggested that stunting in early childhood is caused mainly by chronic enteric diseases( Reference De Boer, Lima and Oría 26 ). A lack of access to safe water results in a cycle of enteric infections. Those infections are associated with a decrease in the absorption of macronutrients and micronutrients and increases in systemic inflammation, and each of these processes may contribute to growth delay. The review also found evidence that such nutritional stunting from enteric disease in early life also has longstanding effects on risk factors for diabetes and CVD( Reference De Boer, Lima and Oría 26 ), which is also related to immune functions.

The present study found that nutritional status at 1 year was related to birth outcome, but did not find any relationship between nutritional status at 2 years and 4·5 years and birth outcome. This suggested that malnutrition in infancy was related to birth outcomes, but not related after 2 years of life. It may suggest that malnutrition at 4·5 years old is related to chronic infection or lack of proper nutritional intake rather than birth outcome.

There are a number of important strengths of the current cross-sectional study including the large sample size and good retention of participants; 76 % of eligible individuals born during the maternal trial were successfully recruited at 4·5 years of age. The sample size of the study was relatively large and the resulting effect estimates exhibited tight confidence intervals, promoting confidence in the results reported.

There were several limitations to the present study. First, it was a cross-sectional study; therefore, the data did not provide direct information on whether stunting is a cause of the development of current wheezing. Second, we used a questionnaire based on the ISAAC to diagnose current wheezing. Wheezing in children may be attributed to allergic asthma, exercise-induced asthma or be a symptom of viral or other respiratory infections. The term wheezing is also often misinterpreted by parents and this may produce overestimation or underestimation of the symptoms. However, the ISAAC questionnaire has been extensively used worldwide and it has reportedly provided an acceptable estimation of the prevalence of asthma in children 2–6 years of age( Reference Takeuchi, Zaman and Takahashi 27 ). Third, information on serum micronutrient values was not available, although it is likely that stunted children also lack critical micronutrients. It has been hypothesized that prenatal vitamin D deficiency may affect fetal lung and immune system development and that it is likely to be exacerbated by postnatal vitamin D deficiency( Reference Litonjua and Weiss 28 ). A systematic review and meta-analysis have shown that insufficient intake of maternal vitamins A, C, D and E were risk factors for developing asthma in children( Reference Nurmatov, Devereux and Sheikh 4 ). It was also found that higher maternal intake of vitamin D and E during pregnancy was associated with reduced risk of wheezing in children( Reference Litonjua and Weiss 28 ). Our preliminary data including 123 children, whose cord blood vitamin levels and wheezing status at 4·5 years are available, showed no association between cord blood vitamin D status and current wheezing symptom in children (MDH Hawlader, unpublished results). However, because of the small sample size, more work needs to be done to examine the relationship between serum vitamin levels and wheezing.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that chronic undernutrition has an influence on current wheezing in rural Bangladeshi children. Further analysis is required to examine the exact mechanism between nutritional factors and asthma and allergic responses in populations, such as in rural Bangladesh, with a high degree of undernutrition and a growing prevalence of asthma and atopic disease.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: The study was supported by the icddr,b; the UK Medical Research Council; the Swedish Research Council; the UK Department for International Development; the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS Grant #18256005); the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative; Uppsala University; the US Agency for International Development under the Cooperative Agreement #388-G-00-02-00125-00; the Australian International Development Agency; the Government of Bangladesh; the Canadian International Development Agency; the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; the Government of the Netherlands; the Government of Sri Lanka; the Swedish International Development Cooperative Agency; and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest. Authors’ contributions: M.D.H.H. conducted the analysis and write-up the paper as a part of his PhD study; S.E.A. and L.A.P. designed the MINIMat study; Y.W., E.N., S.E.M. and R.R. designed the follow-up study at 4·5 years; Y.W. provided logistical support as well as supervised the analysis and manuscript writing. Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to the study participants for their involvement in the study. They thank the field team members and data management staff for their excellent work. They also thank Dr Enbo Ma for his scientific advice on data analysis and valuable comments to improve the manuscript; and Brian Purdue for his professional, native-speaking English revision.