A healthy diet during childhood is essential for optimal physical and cognitive growth and development(1), which may reduce the risk of many non-communicable diseases including diabetes, obesity, CVD, certain cancers and oral disease(2). The Australian Dietary Guidelines recommend that from 12 months of age children consume items daily from the five ‘core’ food groups: fruit, vegetables and legumes, meat and alternatives, cereals and dairy/alternatives and drink plenty of water(1), whilst intake of energy-dense and nutrient-poor discretionary items such as soft drink (sodas), cakes and biscuits should be limited(1). Existing research shows a diet containing discretionary food and beverage items at a young age is associated with increased incidence of dental caries(Reference Dye, Shenkin and Ogden3,Reference Reisine and Douglass4) and obesity(Reference Monasta, Batty and Cattaneo5).

In addition to diet, it is important to establish good oral hygiene habits at a young age to maintain a healthy mouth(Reference Gussy, Waters and Walsh6). Despite being largely preventable, early signs of dental caries have been seen in children as young as 6–12 months of age(Reference Gussy, Ashbolt and Carpenter7) and recent data show 26·1 % of Australian 5- to 6-year-old children have at least one decayed tooth(Reference Do and Spencer8). Early childhood caries can have wide-ranging negative short- and long-term consequences including pain, difficulty eating and missing school(Reference Naidu, Nunn and Donnelly-Swift9,Reference Jackson, Vann and Kotch10) and is one of the best predictors of future decay(Reference Wandera, Bhakta and Barker11).

Children’s early years of life are a critical period during which eating habits and food preferences are established(Reference Birch and Doub12,Reference Savage, Fisher and Birch13) , and evidence suggests that dietary patterns developed in these early years track through to adolescence and into adulthood(Reference Mikkila, Rasanen and Raitakari14). The foods and beverages that children consume during these early years are influenced by a wide range of factors. In the very early years, these are primarily influenced by parents and include feeding style, role modelling, food availability and parental beliefs and attitudes(Reference Patrick and Nicklas15,Reference Paes, Ong and Lakshman16) . However, as children grow and spend time in a wider range of settings including childcare, environmental factors including peer and caregiver role modelling, television viewing and food sources (e.g., childcare) influence what they consume(Reference Patrick and Nicklas15).

In Australia, young children are cared for in a range of formal (e.g., long day care – centre-based childcare for all or part of the day, family day care – childcare based in the home of a registered childcare provider) and informal (e.g., relatives, friends) settings. Children between 1 and 4 years of age have the highest usage rates of childcare in Australia, with around 60 % attending some sort of childcare(17). At age 3 and 4 years, respectively, 55 % and 42 % of children attend formal childcare and around 37 % attend informal childcare(17). Children attending formal childcare do so for an average of 15 h/week, whilst children in informal childcare are there for on average 12 h/week(Reference Baxter18).

The National Quality Framework (https://www.acecqa.gov.au/nqf/about), implemented in 2012, requires formal childcare services in Australia to promote healthy eating and provide nutritious foods and beverages for children(19). Whilst this is likely to influence oral health through regulating food and beverage consumption, there are no benchmarks that directly target oral hygiene behaviours such as tooth brushing. To meet the National Quality Framework benchmarks, many formal childcare services have developed nutrition policies and guidelines. In Australia, the Romp and Chomp Intervention(Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Elea and Bell20–Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Bell and Kremer22) and the Start Right, Eat Right programme(Reference Bell, Hendrie and Hartley23) have shown the positive effect of policy and guidelines on the nutrition environment and food consumption in formal childcare settings. However, the extent to which these guidelines are adhered to across all settings is unclear, with recent evidence suggesting that discretionary items are available on a regular basis at childcare centres(Reference Wallace, Costello and Devine24).

In contrast to the regulations in formal childcare settings, there are no requirements to have such structured guidelines in informal childcare. Anecdotal evidence suggests parents may have formal or informal agreements regarding their expectations for their child’s nutrition and oral health, with those who provide informal childcare; however, there is little evidence for the impact of these on the childcare environment or outcomes for their child.

Most interventions with nutrition outcomes have focused on formal childcare settings or preschools and the role that nutrition plays in obesity(Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Elea and Bell20,Reference Mikkelsen, Husby and Skov25,Reference Jones, Wyse and Finch26) . The literature exploring oral health and childcare has primarily focused on policies and practices in formal childcare settings(Reference Scheunemann, Schwab and Margaritis27–Reference Kranz and Rozier29), rather than oral health outcomes for children. There is some research examining nutrition outcomes for children in different types of childcare. In the USA, data from 10 700 children in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study showed that a greater time spent in non-relative or centre-based childcare was associated with a lower consumption of soft drinks, and that vegetable consumption was positively associated with time spent in centre-based childcare(Reference Mandal and Powell30).

Poor oral health can have a profound impact on children’s health and quality of life. Behaviours that influence oral health, such as dietary intake, dental visiting and oral hygiene, are influenced by the environment children are exposed to. Many preschool children attend some sort of childcare; however, little is known about the relationship between childcare, oral health and dietary intake. The aims of this study were to (i) examine the consumption of foods and beverages and oral health factors when children are aged 3 and 4 years and (ii) explore associations between type of childcare and (a) food and beverage consumption and (b) oral health factors.

Methods

Study design

The VicGen birth cohort study

The VicGen birth cohort study was established to explore the development of early childhood caries(Reference Johnson, Carpenter and Amezdroz31). The study was designed to have an emphasis on social disadvantage (e.g., low income, low education), cultural diversity and a mix of locations (metropolitan, regional and rural), and as such participants were recruited from seven local government areas (administrative divisions within a state) in the western corridor of Victoria, Australia. Nurses from the Maternal and Child Health Service in these areas invited families who were attending their newborn’s 2- or 4-week health check to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included intention to move from the area in the next 12 months, children requiring specialist paediatric childcare, severe illness in family and presence of parental mental illness. Over a 2-year period, 466 newborn infants were recruited into phase I of the study, and data were collected at child aged 1, 6, 12 and 18 months (waves 1–4). Parents were then asked if they wished to continue in phase II, involving a further three waves at child aged 3, 4 and 5 years. Each of the seven waves comprised a child oral examination, a child saliva sample and a parent-completed questionnaire. One oral health professional and one research assistant attended each study visit, with the majority conducted at the participant’s home. A small number of study visits were conducted at Maternal and Child Health centres or community halls. A detailed description of the study has been published(Reference Johnson, Carpenter and Amezdroz31).

Data for the current analysis came from waves 5 (age 3 years) and 6 (age 4 years), collected between February 2012 and January 2015. These waves contained the information on childcare required for the analysis. The VicGen study was a longitudinal cohort; however, there were several children for whom data were only available at wave 5 or wave 6. Therefore, to maximise the available n in this paper, data were analysed as two cross-sectional samples.

Questionnaire

A paper-based questionnaire was mailed to the child’s primary caregiver (majority mothers) to complete approximately 2 weeks prior to the study visit for each wave of data collection. Researchers collected the completed questionnaire when they conducted the study visit. In cases where the participant had not completed the questionnaire, they were supplied a reply-paid envelope for return via mail. An FFQ, asking capturing the usual weekly consumption of forty-six foods and beverages (no time frame specified) known to influence oral health, was included in the questionnaire. The questionnaire has been validated for use with children in this age group but did not capture all foods and beverages that children may have consumed. Parents were asked to report how often their child usually consumed fifteen core foods (e.g., fruit, vegetables and cereal), eighteen discretionary foods (e.g., hot chips, lollies/chocolate and cakes) and thirteen beverages (e.g., water, milk and fruit juice). There were eight discrete response options for foods ranging from never to ≥4 times/d, whilst for beverages, parents were asked to report how often per day or week or month their child consumed the item. The questionnaire also collected information on the parent’s rating of their child’s oral health (five-point scale: poor to excellent), child tooth brushing frequency and dentist/dental clinic visit frequency. The type of childcare (none (parent only), family day care, childcare centre, paid babysitter/nanny, grandparent, relative, friend/neighbour and other) that the child had received in the last month was also collected. The number of h/week spent in each childcare type was collected at age 4 years only.

Data handling and analysis

The independent variable, type of childcare, was collapsed into four categories: parent care only (PCO had not used any form of childcare), formal childcare only (FCO: family day care, childcare centres) informal childcare only (ICO: paid babysitter/nanny, grandparents, relatives and friends/neighbours) and mixed formal/informal care (a combination of the two categories). As the number of hours was only collected at age 4 years, the duration of time in childcare was not included in both analyses. For children attending informal and formal care, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the potential influence of the proportion of time spent in these types of childcare.

The most commonly consumed foods and beverages were included in the analysis (discretionary foods: ≥19 % consuming at least once a week, core foods: ≥75 % consuming at least once/week (except for meat/fish and bread) and beverages: ≥10 % reported to consume beverage). Water was excluded from analysis due to the lack of variation in consumption frequency. Cut-off points were determined after examining the spread of responses in the data.

All outcome variables were dichotomised. Foods and beverages were collapsed into the following categories: core items (cheese, yogurt, banana, fruit, vegetables and plain milk): <once a day, ≥once a day; discretionary items (muesli/fruit bars, ice cream, sweet biscuits, cakes/muffins, lollies/chocolate, potato chips, hot chips, savoury biscuits, fruit juice, cordial, soft drink and flavoured milk): <twice a week, ≥twice a week. Food and beverage items were collapsed based on the current Australian Dietary Guidelines(1) and clinical judgement of a practicing paediatric dietitian (personal communication). Oral health variables were collapsed into the following: brushing frequency: ≤once/d, >once/d; parent rating of child’s oral health: poor/fair/good, very good/excellent; child has ever visited a dental clinic: yes/no. Oral health items were collapsed based on current recommendations for best oral healthcare practice(32).

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the childcare type used at each age. The χ 2 statistic and the Fisher’s exact test (where cell frequency ≤5) were used to examine associations between the type of childcare and outcome variables at each age. Variables with significant associations were examined using univariable and multivariable logistic regression. Analyses were adjusted for variables which may influence nutrition and oral health, including child age, child gender, family health childcare card status at child aged 3 and 4 years (a means-tested card entitling the holder to certain concessions such as reduced cost medications) and area (metropolitan, regional and rural) in which child was born (collected at baseline). Baseline area was included because accurate residential location was not available when children were 3 and 4 years of age. Analyses were conducted using Stata 14 with a significance level of P < 0·05.

Results

Sample characteristics

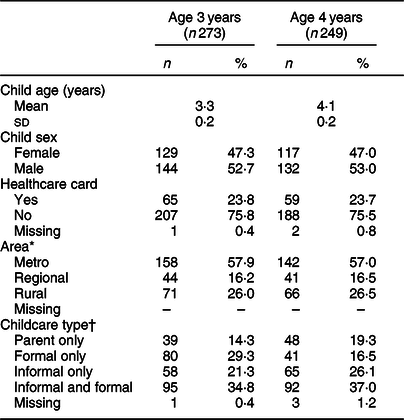

Table 1 displays the sample characteristics and the type of childcare used in the previous month at age 3 and 4 years. The breakdown of child gender, healthcare card status and area of residence at birth was similar at each wave. The most common type of childcare at each age was a mixture of formal and informal childcare. Compared with age 3 years, PCO was more common at age 4 years (14·3 v. 19·3 %), and FCO was less common (16·5 v. 29·3 %). There were 241 families with valid data at age 3 and 4 years, and 42·3 % of these reported using a different type of childcare at age 4 compared with age 3.

Table 1 Sample characteristics of VicGen participants at age 3 and 4 years

* Area child was born.

† Thirty-one children had valid data at age 3 years but not age 4 years, five children had valid data at age 4 years but not age 3 years.

Core and discretionary foods and beverages

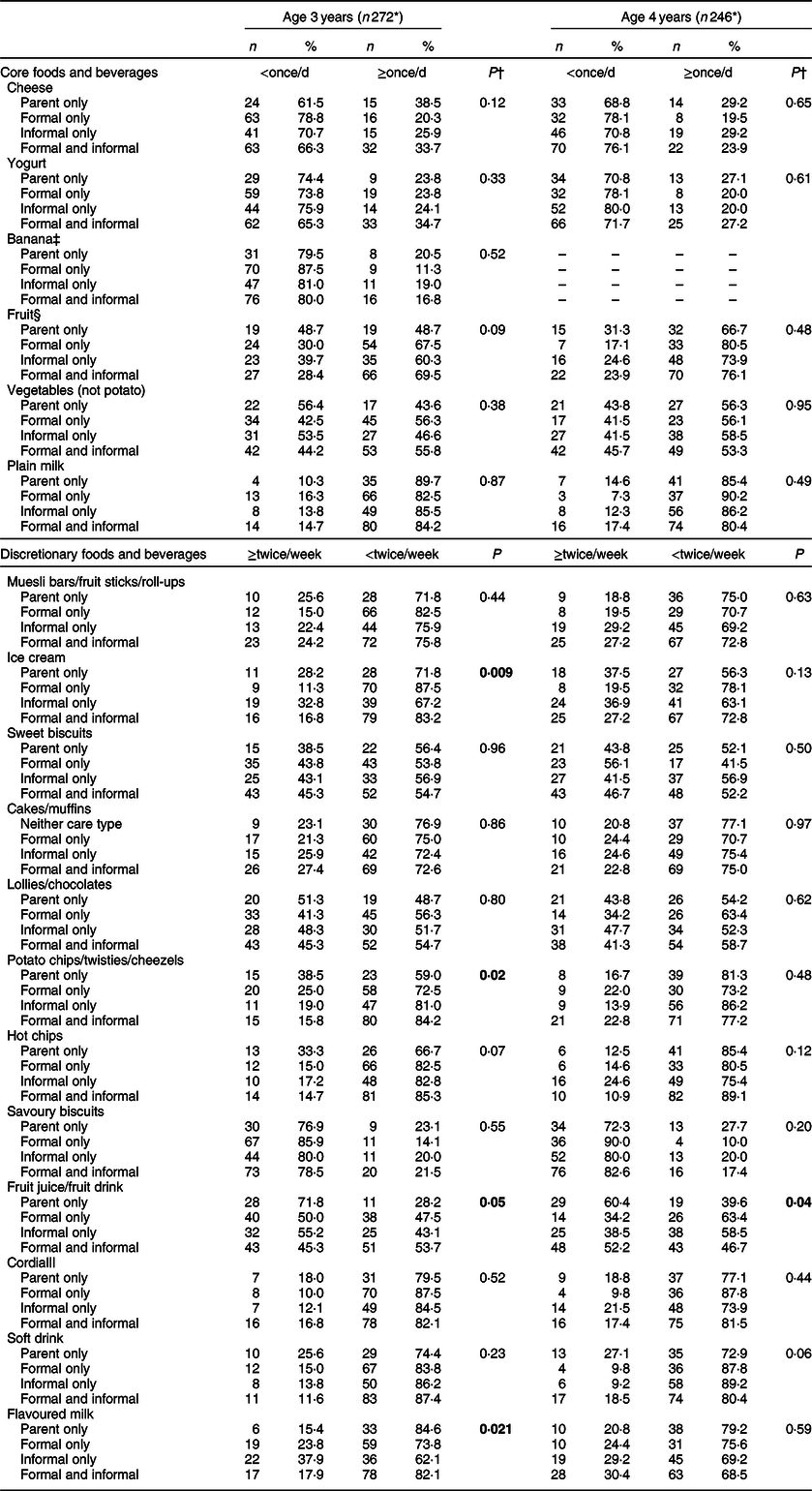

Table 2 shows the frequency of consumption of food and beverage items according to childcare type at age 3 and 4 years. No significant associations between childcare type and consumption frequency were observed in any of the core foods at either age. For discretionary items after adjusting for covariates, significant associations between childcare type and consumption frequency were observed for ice cream, potato chips (crisps), flavoured milk (age 3 years only) and fruit juice (age 3 and 4 years). Hot chips and soft drink neared significance (P = 0·07 and 0·06, respectively), and it was decided to include them in the logistic regression models for further exploration.

Table 2 Food and beverage consumption frequency by childcare type at age 3 and 4 years of the VicGen cohort

The bolded values are those which are statistically significant.

* n varies due to missing values.

† χ 2 value or Fisher’s exact (where frequency ≤5).

‡ Banana was included as a separate item in the 3-year-old questionnaire but not in the 4-year-old questionnaire.

§ Age 3: fresh fruit, excluding banana; wave six: fresh or stewed fruit.

|| Syrup mixed with water.

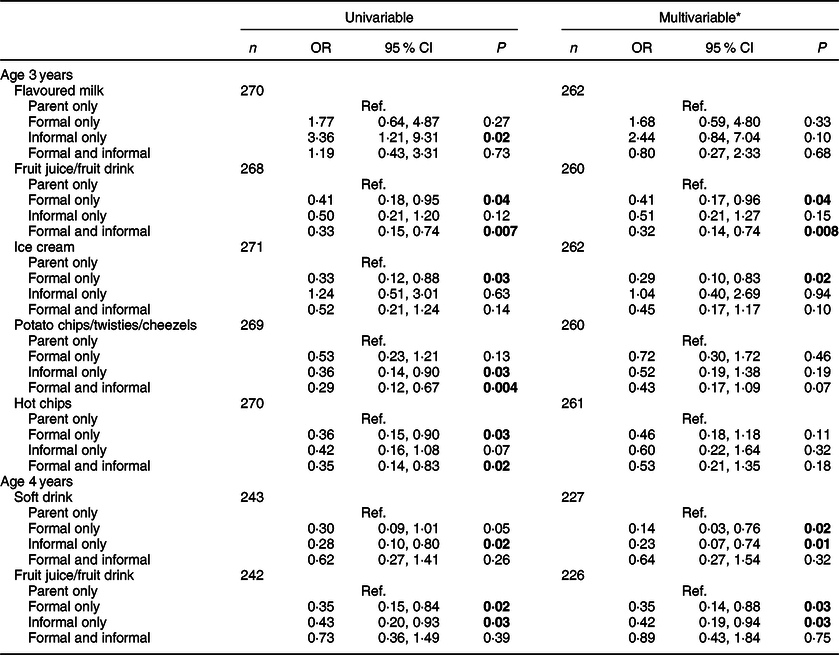

At age 3 years, in adjusted models, children who were in formal childcare or a mixture of informal and formal childcare were less likely to consume fruit juice twice a week or more, compared with children who were in PCO (FCO: adjusted OR (AOR) 0·41, 95 % CI 0·17, 0·96, P = 0·04; mixed formal/informal care: AOR 0·32, 95 % CI 0·14, 0·74, P = 0·008). Children who were receiving FCO were 71 % less likely to be consuming ice cream (95 % CI 0·10, 0·83, P = 0·02) at least twice a week than children who were in PCO (Table 3).

Table 3 Univariable and multivariable logistic regression for the indicator variable against each food and beverage outcome

The bolded values are those which are statistically significant.

* Models adjusted for child age, child gender, healthcare card (yes/no) and area.

At age 4 years, in adjusted models, similar trends were seen for two sweet beverages. Children who were receiving FCO or ICO were less likely to be consuming soft drink (FCO: AOR 0·14, 95 % CI 0·03, 0·7, P = 0·02; ICO: AOR 0·23, 95 % CI 0·07, 0·74, P = 0·01) and fruit juice/fruit drink (FCO: AOR 0·35, 95 % CI 0·14, 0·88, P = 0·01; ICO: OR 0·42, 95 % CI 0·19, 0·94, P = 0·03) at least twice per week compared with children in PCO.

The sensitivity analysis for children who spend time in both formal and informal childcare showed no significant association between soft drink or fruit juice/drink consumption and the proportion of time children spend in either type of childcare each week.

Oral health measures

No associations were seen in brushing frequency, oral health rating or dental visiting when comparing childcare types (Table 4). Low rates of optimal tooth brushing were seen across all childcare types at age 3 and 4 years, with 51 % or less reported to be brushing twice a day. Low rates of dental visiting were also seen with around 45 % of children reported to have never been to a dentist or dental clinic by 4 years of age.

Table 4 Distribution of oral health measures by childcare type at age 3 and 4 years of the VicGen cohort

* n varies due to missing values.

† χ 2 or Fisher’s exact (where frequency ≤5), without missing values.

Discussion

This research has explored food and beverage consumption and oral health-related factors in a cohort of Australian children aged 3 and 4 years. It has shown associations between the types of childcare these children experience and the frequency with which they consume particular discretionary foods and beverages. No associations were observed between childcare type and core food consumption, tooth-brushing, dental visiting or parent-reported child oral health status. However, childcare type was significantly associated with the consumption of discretionary items, particularly sweet beverages – fruit juice/fruit drink and soft drink, and ice cream across these ages, which are associated with increased risk of dental disease.

In the current study, the intake of core foods and beverages such as fruits, vegetables and milk was similar across the different types of childcare. Across all childcare groups, many children consumed fruits and vegetables less than once a day (30–51 % of children aged 3 years and 19–33 % of children aged 4 years). The dietary guidelines recommend children of this age consume 2½ to 4½ servings of vegetables and 1 to 1½ servings of fruit each day. It is unlikely that children who do not consume these items daily are meeting their recommended intake(33). A substantial proportion of children were consuming discretionary items twice a week or more, and the results suggest that many children are consuming multiple discretionary items more than twice a week. The dietary guidelines recommend children aged under 8 years avoid discretionary items or restrict consumption to ½ a serving per day(34). The cumulative intake of multiple discretionary items suggests that many children in this study are exceeding these recommendations. Discretionary food consumption can displace core foods, which contain the nutrients and energy children need to develop(34,Reference Johnson, Bell and Zarnowiecki35) . Discretionary foods also tend to be high in salt and sugar, and regular provision may encourage children to develop a preference for these flavours(Reference Birch36). There is evidence that children’s dietary intake may track across time(Reference Mikkila, Rasanen and Raitakari14,Reference Spence, Campbell and Lioret37) and high consumption of discretionary items can lead to excessive energy intake. In the long term, this can cause weight gain and increase the risk of diabetes, CVD and tooth decay(Reference Maffeis and Tato38,Reference Tinanoff and Palmer39) .

At 3 years of age, compared with children receiving PCO, children attending FCO were 59 % less likely to be consuming fruit juice/drink and 71 % less likely to be consuming ice cream. Children attending a mixture of formal and informal childcare were 68 % less likely to be consuming fruit juice/drink. At 4 years of age, associations were only seen with sweetened beverages – fruit juice/drink and soft drink – with children attending either FCO or ICO, 58–86 % less likely to be consuming these beverages compared with children in PCO. Although these results were statistically significant, the wide CI indicate the magnitude of association may be much smaller (as low as 4 %) or higher (88 %) than observed. Fruit juices and fruit drinks tend to be perceived as healthier than soft drinks(Reference Bucher and Siegrist40), despite being similar in terms of energy density, sugar content and the detrimental effect on teeth(Reference Birkhed41). Although 100 % fruit juice may have some beneficial nutrients and are counted as one serve of fruit in the Australian Dietary Guidelines(1), they lack the fibre and are less satiating than a piece of whole fruit(Reference Bolton, Heaton and Burroughs42,Reference Flood-Obbagy and Rolls43) . Additionally, young children innately preference sweet flavours(Reference Birch36), so providing fruit juice and fruit drinks at an early age can encourage them to preference these beverages over water and milk.

There are few published studies comparing dietary intake by type of childcare and those that exist focus on formal childcare settings rather than informal childcare. In Finland and Canada, children in formal childcare were less likely to consume soft drink compared with those not in childcare, but no difference in fruit juice consumption was observed(Reference Lehtisalo, Erkkola and Tapanainen44,Reference Pabayo, Spence and Cutumisu45) . This is interesting considering both fruit juice and soft drink were less likely to be consumed by children attending care in the current study. The timing of data collection may provide some explanation for these differences, with data from Canada and Finland collected in the mid-2000s, whilst data for VicGen were collected from 2011 onwards. The increased focus on childhood obesity rates in the early to mid-2000s(Reference Hesketh and Campbell46,Reference Swinburn and Wood47) encouraged the introduction of nutrition policies in many early childhood services(Reference Montague48). Policies tended to promote water and milk as the only beverages offered to children in these settings whilst discouraging sweet beverages, including fruit juice(Reference de Silva-Sanigorski, Bell and Kremer21,Reference Mazarello Paes, Hesketh and O’Malley49,Reference Ritchie, Sharma and Gildengorin50) . Compared with the Canadian and Finnish children in these studies, children in the VicGen study may have been more likely to be attending childcare where beverage policy may have been implemented for many years.

In addition to childcare centre policies, in early 2012, the National Quality Framework introduced new quality standards across formal childcare settings in Australia, which included guidelines in relation to the provision of nutritious foods in formal childcare settings(19). Childcare services are assessed on seven quality areas and given a rating, which they must display at their centre. Services must meet a certain standard or be working towards the standard to continue operating. The implementation of this framework commenced around the same time as 3-year-old data collection in this study, and it is likely that the potential effects of the framework were not immediately seen as services worked towards meeting the benchmarks. The nutrition component of the National Quality Framework is relatively small, and the degree to which services adhere to these guidelines is unclear, with recent research showing discretionary foods are regularly offered at childcare centres(Reference Wallace, Costello and Devine24). This is additionally complicated across family day care services, where carers provide childcare out of their own home to a small number of children. The ratio of food provided by the childcare provider to food provided by parents may vary across different family day care services.

The reasons for consumption differences between children attending ICO and a mixture of formal and informal childcare are more difficult to ascertain given the lack of existing evidence about what occurs in informal childcare settings. We theorised that formal childcare policy and guidelines may account for the associations seen with children in a mixture of childcare types. However, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to explore this at age 4 years and there were no associations between the proportion of time children spent in each type of childcare and their consumption of soft drink or fruit juice/drink. This suggests that factors across the formal and informal childcare environment may influence beverage intake for these children. Additionally, the differences seen between ICO and PCO warrant further exploration. Grandparent care is the most common type of informal childcare used in Australia(17); however, there is little published evidence about food and beverage consumption in this environment. Traditionally, grandparents have been considered treat givers and parents tend to report their children are likely to receive unhealthy foods and beverages from grandparents(Reference Roberts and Pettigrew51). However, emerging research has challenged this with grandparents who have reported the healthiness of an item as the main influence on the foods and beverages they provide to their grandchildren(Reference Jongenelis, Talati and Morley52). Additional evidence suggests that as the amount of time a grandparent cares for their grandchild each week increases, they tend to provide more parent-like care, where unhealthy foods and beverages are limited(Reference Farrow53). Further research into grandparent childcare is warranted to explore the provision of foods and beverages in this environment.

The oral health variables used in this study were selected to capture parent reports of overall oral health, dental visiting patterns and oral hygiene behaviours. While no significant relationship was observed between childcare type and any of these variables, this analysis has identified oral health practices that fall short of recommendations. To maintain good oral hygiene, teeth should be brushed twice a day(54); however, at age 3 years, only 30–40 % of children across all childcare types were brushing their teeth more than once a day, and this increased only slightly by age 4 years. These results suggest oral health promotion strategies targeted at families during this time were not eliciting the desired behaviours in this group and reasons for this need to be explored. It is also recommended that children visit a dental professional by the time they are 2 years old(54). In 2011, all children under 12 year of age were eligible for general dental services through the public system and had priority access(55); however, only 18–36 % of 3 year olds and just over 50 % of 4 year olds in this sample had visited a dental professional. Some families considered the oral health check they received as part of the VicGen study to be sufficient, as reported anecdotally during study visits. Geographical barriers may have also played a role, given that a large proportion of this cohort resided in rural areas and only two-thirds of those eligible for public dental care in rural areas live within a 20 km radius of a public dental clinic(56). The reasons behind not visiting a dental professional are likely to be multi-factored and will be explored in further publications from the VicGen study.

In Victoria, most parents will receive oral health information from the Maternal and Child Health Service at their child’s 8-, 12- and 18-month health checks. However, there is limited published evidence around the implementation and effectiveness of other oral health promotion strategies in different childcare settings in Victoria. There is evidence around the effectiveness of an outreach programme where dental professionals visit preschools and reduce barriers to attending dental services(Reference Mason, Mayze and Pawlak57), which could theoretically be applied to childcare services. Currently, Smiles 4 Miles(58) and the Achievement Program(59) are two ongoing programmes run statewide that have a focus on oral health promotion. At the time of data collection, however, very few childcare services were participating in Smiles 4 Miles, with the focus on participation of kindergartens. The Achievement Program, whilst targeting childcare services, was in its infancy at this stage, with oral health messaging starting to be incorporated into the programme. The potential influences of these programmes are unlikely to have had an effect by the time of data collection for the VicGen cohort, but families may be influenced by the structure and expansion of these programmes over time.

The results presented must be interpreted in the context of the limitations of this research. The sample includes participants from metropolitan, regional and rural Victoria but may not necessarily be representative of the broader population. The FFQ captures a broad range of core and discretionary foods and beverages; however, as it was designed for use in relation to oral health, it only measures the frequency with which items are consumed, not the actual amount as no serving size was specified. Also, parents may not always know what their child is consuming if they are not in their care. The care-type measure is also relatively crude. Parents reported childcare during a typical week over the last month, which may not represent the childcare their child usually receives. Additionally, both measures were parent reported and thus open to bias compared with more objective measures. There may also be potential differences in the types of informal childcare (e.g., grandparents v. nannies v. friends) that make a difference to these outcomes that are not captured in these data.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that, in 3- and 4-year-old children, attending childcare is associated with less frequent consumption of soft drinks and fruit juice/drink but not associated with the consumption of core foods or most discretionary foods. Childcare was not associated with the oral health and hygiene indicators; overall however, many children were not brushing their teeth twice daily and had not yet seen a dental professional, both of which are recommended for good oral health. Further investigation of healthy eating and oral health in the childcare environment is needed, particularly in informal childcare. There is little understanding of what and how different factors in the informal care environment help or hinder the promotion of healthy eating and good oral health and hygiene. Gaining insight into this environment will help to ascertain which strategies may be transferable to other childcare settings, and potentially PCO, as well as identifying areas where care providers may require additional support. Further research with families who do not use childcare is also warranted to explore the reasons for more frequent consumption of some discretionary items by children in this environment. Understanding factors unique to this context will help identify if and how existing child nutrition and oral health messages reach families. It will also help to identify the barriers and enablers of promoting healthy behaviours in PCO.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge all the families who have participated in the study and the Maternal and Child Health Nurses and administration staff who assisted with recruitment. The authors also acknowledge Associate Professor Andrea de Silva, the former leader of the VicGen study as well as the project staff who have been involved at different stages. This research was supported by The National Health and Medical Research Council, Dental Health Services Victoria, Financial Markets Foundation for Children, Jack Brockhoff Foundation, La Trobe University, Oral Health Cooperative Research Centre and the Victorian Government Department for Education and Training. The authors dedicate this paper to the memory of Professor Elizabeth Waters whose leadership, vision and vitality will never be forgotten. Financial support: Financial support for this research came from The National Health and Medical Research Council (Project Grant APP425829), The Financial Markets Foundation for Children (Project Grant 2011-161) and the Victorian Government Department of Education and Training. Additional salary support was received from The Jack Brockhoff Foundation. In-kind support was received from La Trobe University and the Oral Health Cooperative Research Centre. L.C. was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Postgraduate Scholarship (GNT109370). Funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: L.C. contributed to the conception, design, data analysis and interpretation and prepared the draft manuscript. L.G. and A.M. assisted with the interpretation of the data and provided critical review of manuscript drafts. S.D., M.G. and H.C. conceptualised the VicGen Study and provided critical review of manuscript drafts. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 0722543 and HREC 1137124). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.